University of Texas at El Paso University of Texas at El Paso

ScholarWorks@UTEP ScholarWorks@UTEP

Departmental Technical Reports (CS) Computer Science

8-2004

Non-Lexical Conversational Sounds in American English Non-Lexical Conversational Sounds in American English

Nigel Ward

The University of Texas at El Paso

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/cs_techrep

Part of the Computer Engineering Commons

Comments:

UTEP-CS-04-22.

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Ward, Nigel, "Non-Lexical Conversational Sounds in American English" (2004).

Departmental Technical

Reports (CS)

. 307.

https://scholarworks.utep.edu/cs_techrep/307

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Computer Science at ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has

been accepted for inclusion in Departmental Technical Reports (CS) by an authorized administrator of

ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Non-Lexical Conversational Sounds

in American English

Nigel Ward

nigelw[email protected]

phone: 915-747-6827

fax: 915-747-5030

http://www.cs.utep.edu/nigel/

Computer Science, University of Texas at El Paso

El Paso, TX 79968-0518

0

Acknowledgements: I thank Takeki Kamiyama for phonetic label checking, Gautam Keene and Andres

Tellez for pragmatic function labeling and discussion, and all those who let me record their conversations. For

general discussion I thank Daniel Jurafsky and Kazutaka Maruyama. I would also like to thank Keikichi Hirose,

the Japanese Ministry of Education, the Sound Technology Promotion Foundation, the Nakayama Foundation,

the Inamori Foundation, the International Communications Foundation and the Okawa Foundation for support.

Most of this work was done at the University of Tokyo.

Non-Lexical Conversational Sounds

in American English

Abstract

Sounds like h-nmm, hh-aaaah, hn-hn, unkay, nyeah, ummum, uuh and um-hm-uh-

hm, occur in American English conversation but have thus far escaped systematic

study. This article reports a study of both the forms and functions of these items,

together with related tokens such as um and uh-huh, in a corpus of American Eng-

lish conversations. These sounds appear not to be lexical, in that they are pro-

ductively generated rather than finite in number, and in that the sound-meaning

mapping is compositional rather than arbitrary. This implies that English bears

within it a small specialized sub-language which follows different rules from the

language as a whole. This functions supported by this sub-language complement

those of main-channel English; they include low-overhead turn-taking control, ne-

gotiation of agreement, signaling of recognition and comprehension, management

of interpersonal relations such as control and affiliation, and the expression of

emotion, attitude, and affect.

Biographical Note: Nigel Ward received a Ph.D. from the University of California

at Berkeley in 1991. From 1991 to 2002 he was with the University of Tokyo. His

primary research interest is human-computer interaction, especially sub-second

responsiveness in spoken dialog systems.

2

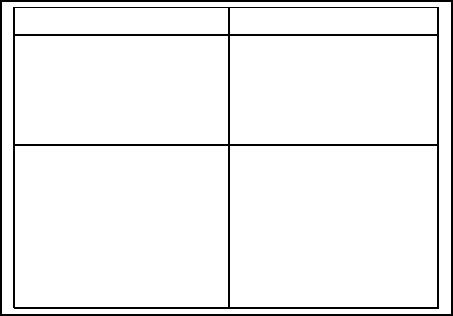

[clear-throat] 2 hh-aaaah 1 nuuuuu 1 uam 1 uumm 1

[click] 22 hhh 1 nyaa-haao 1 uh 36 uun 1

[click]neeu 1 hhh-uuuh 1 nyeah 1 uh-hn 2 uuuh 1

[click]nuu 1 hhn 1 o-w 1 uh-hn-uh-hn 1 uuuuuuu 1

[click]ohh 1 hmm 2 oa 1 uh-huh 3 wow 1

[click]yeah 1 hmmmmm 1 oh 20 uh-mm 1 yah-yeah 1

[noisy-inhale] 1 hn 1 oh-eh 1 uh-uh 2 ye 1

achh 1 hn-hn 1 oh-kay 1 uh-uhmmm 1 yeah 70

ah 6 huh 2 oh-okay 2 uhh 4 yeah-okay 1

ahh 1 i1oh-yeah 1 uhhh 1 yeah-yeah 1

ai 1 iiyeah 1 okay 8 ukay 2 yeahh 2

am 1 m-hm 2 okay-hh 1 um 20 yeahuuh 1

ao 1 mm 2 ooa 1 um-hm-uh-hm 1 yegh 1

aoo 1 mm-hm 1 ookay 1 umm 5 yeh-yeah 1

aum 5 mm-mm 1 oooh 1 ummum 1 yei 1

eah 1 mmm 3 ooooh 1 unkay 1 yo 1

ehh 1 myeah 2 oop-ep-oop 1 unununu 1 yyeah 1

h-nmm 1 nn-hn 4 u-kay 1 uu 6

haah 1 nn-nnn 1 u-uh 4 uuh 1

hh 3 nu 1 u-uun 1 uum 6

Table 1: All Conversational Non-Lexical Sounds in the Corpus, with numbers of occurrences

1 INTRODUCTION

American English conversations are sprinkled with large variety of non-lexical sounds, as

suggested by Table 1. Along with such familiar items as oh, um, and uh-huh, there are a large

number of less common sounds such as h-nmm, hh-aaaah, hn-hn, unkay, nyeah, ummum, uuh

and um-hm-uh-hm. Similar variety is also seen in Swedish (Allwood & Ahlsen 1999), German

(Batliner et al. 1995) and Japanese (Ward 1998).

While many aspects of non-lexical items in conversation been studied, these uncommon

sounds have mostly escaped notice. In particular two basic questions have not been raised,

much less addressed: first, the reason for such a large variety of sounds, and second, what

they all mean.

More generally, non-lexical items have long been an area of central interest within the study

of conversation, human communication, and interpersonal interaction (Yngve 1970; Duncan

& Fiske 1985; Schegloff 1982). Although such phenomena have been viewed as the place to

begin the scientific study of language (Yngve 1970) or as possibly providing a ‘grounding of

language in discourse and social interaction’ (Langacker 2001), they have in fact remained at

the margins of linguistic interest. This article will show that non-lexical utterances do, after

all, bear on a central issue, that of the nature of language as a ‘system relating sounds and

3

meanings’.

The structure of this paper is as follows. The first three sections illustrate the phenom-

ena, survey the current state of knowledge, explain the practical importance, and outline the

overall approach. Section 4 presents a phonetic description and argues that most non-lexical

conversational items, including both the rare and the common forms, are productive com-

binations of 10 component sounds. Sections 5, 6, and 8 present meanings for each of these

component sounds, and evaluate the power of a Compositional Model, in which the meaning

of a non-lexical token is the sum of the meanings of the component sounds. The methods

used to identify and check these meanings are presented as they arise, but mostly in Sections

2, 5, and 7. Sections 9 and 10 explore how the model helps clarify the role of non-lexical

utterances in human communication and their relationship to phenomena such as interjection

and laughter. Section 11 summarizes.

2 THE NEED FOR A INTEGRATIVE ACCOUNT

For several reasons a integrative account of non-lexical items in conversation is needed. Al-

though aspects of these phenomena have been addressed by a large number of studies, under-

taken with a variety of aims, there has as yet been no attempt to integrate the findings. This

section explains why it is worth doing so.

First, although there are many studies which have focused on one or a few of these items

— for example mm (Gardner 1997), okay (Beach 1993), okay and uh-huh (Hockey 1992),

nyem, ne:uh, and mnuh (Jefferson 1978), yeah and mm-hm (Jefferson 1984), and uh and um

(Brennan & Schober 2001; Clark & Fox Tree 2002; Fox Tree 2002) — the big picture has been

missing. That is, there has b een no attempt to explain how these items function as a system,

meaning that, for example, there is no account of how speakers can chose among these items,

especially the less common ones.

This lack hinders the construction of more useful spoken-dialog systems, in that non-lexical

items have the potential to let spoken dialog systems give the user better, more motivating

feedback, to deliver information more efficiently and smo othly, and in general to make human-

computer more pleasant (Schmandt 1994; Shinozaki & Abe 1998; Thorisson 1996; Rajan et al.

4

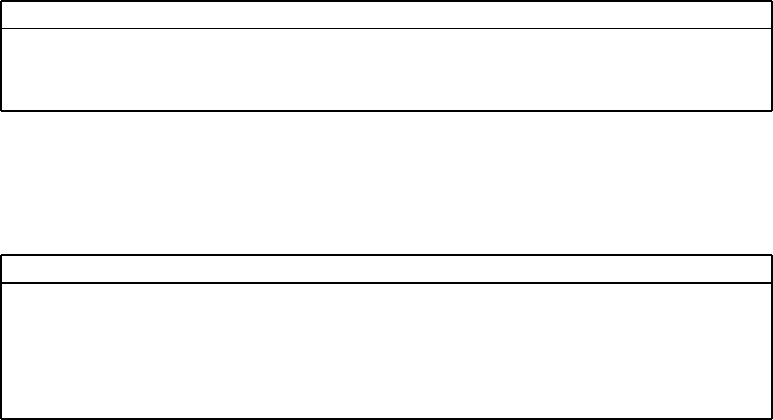

total

back-

channel

filler

dis-

fluency

isolate

res-

ponse

confirm-

ation

final other

[clear-throat] 2 . . 1 . . . . 1

[click] 22 . 12 2 1 . . . 7

ah 6 1 3 2 . . . . .

aum 5 . 4 1 . . . . .

hh 3 . . . 2 . . 1 .

hmm 2 . . . 1 . . . 1

huh 2 . 1 . 1 . . . .

m-hm 2 2 . . . . . . .

mm 2 2 . . . . . . .

mmm 3 2 1 . . . . . .

myeah 2 2 . . . . . . .

nn-hn 4 4 . . . . . . .

oh 20 6 9 . . . . . 5

oh-okay 2 1 . . . 1 . . .

okay 8 2 2 . . 1 2 . 1

u-uh 4 . . 2 . 2 . . .

uh 36 . 13 20 1 . . 1 1

uh-hn 2 2 . . . . . . .

uh-huh 3 3 . . . . . . .

uh-uh 2 . 1 1 . . . . .

uhh 4 . 3 1 . . . . .

ukay 2 1 1 . . . . . .

um 20 . 10 8 . . . 1 1

umm 5 . 5 . . . . . .

uu 6 3 2 . . . . . 1

uum 6 . 4 2 . . . . .

yeah 70 26 19 1 6 6 6 2 4

yeahh 2 2 . . . . . . .

(other) 69 32 18 3 8 3 . 1 4

Total 316 91 108 44 20 13 8 6 26

Table 2: Counts of Non-Lexical Occurrences in various positions and functional roles, for all

items occurring 2 or more times in the corpus

2001; Iwase & Ward 1998; Tsukahara & Ward 2001; Ward 2000a; Ward & Tsukahara 2003).

This lack also hampers learners of English as a second language (Gardner 1998). Today there

is no model or resource that describes even approximately, for example, the relation between

uh and uh-huh, the ways in which the meaning of uh-huh resembles and differs from that of

uh-hn, and when people use myeah instead of yeah. Thus, as a supplement to more detailed

studies, a big-picture account would have great practical value.

Second, although there have been detailed studies of non-lexical utterances within certain

roles, especially disfluencies and back-channels, there has been little work looking at the

distribution of non-lexical items across such roles. This lack of category-spanning studies is

unfortunate since, as McCarthy (2003) notes, many of these sounds are multi-functional. This

5

is

seen also in Table 2: for example, oh occurs both as a back-channel and turn-initially. An

integrative account has the potential to reveal broader generalizations.

Third, although there have been on the one hand several phonetically sensitive studies

of non-lexical utterances, and on the other hand many pragmatically sophisticated studies of

their use in conversation and a few controlled experiments, there has been little connection

between the two: the phonetically sensitive work has said little ab out those variations which

are common in conversation or cognitively significant, and conversely the work based on

conversation or dialog data has not paid much attention to phonetic variation. An integrative

account, looking at variations in form and variations in meaning together, has the potential

to improve our understanding of both aspects.

Ultimately, of course, the reason to seek an integrative account lies is the hope that it will

be simpler overall.

3 APPROACH

To seek an integrative account it was necessary to approach the phenomena in a novel way.

3.1 Working with a Mid-Size Corpus

The basic strategy adopted was to take a mid-sized corpus of casual conversations and try to

understand and explain everything about all of the non-lexical utterances. By looking at all

occurrences it was easier to notice the relations between items and to examine items across a

variety of functional and positional roles.

Conversations were used, rather than task-oriented dialogs or controlled dialog fragments,

to allow the study of diverse dialogs and rich interactions, giving a broader view of when and

how non-lexical utterances are used.

Analysis was limited to a mid-size corpus, rather than a large one, in order to allow a

reasonably thorough examination of the phonetics and pragmatics of each occurrence. This

also made it possible for all the analysis to be done by listening directly to the data, without

having to rely on transcriptions.

A home-made corpus, rather than a standard one, was used because the author was familiar

with it, as the sound engineer recording the conversations, as a friend or acquaintance of most

6

of

the conversants, and as a participant in a few of the conversations. (The author’s own

non-lexical utterances were excluded from the analysis.) The extra information this gave was

often helpful when interpreting ambiguous utterances.

The corpus used includes 13 different speakers, male and female, all American, aged from

20 to 50ish, from a variety of geographical areas. Most of the conversations were recorded

for another purpose (Ward & Tsukahara 2000), and participants were not informed of the

interest in non-lexical utterances. In some cases people were brought together to converse

and be recorded, other times the conversations were already in progress. All recordings had

only two speakers, and in most cases these two were doing nothing but conversing with each

other, although some conversations included interactions with other people or pets, and one

speaker was driving. Recording locations included the laboratory, living rooms, a conference

room, a hotel lobby, a restaurant, and a car. The relationships between conversants ranged

from relatives to close friends to acquaintances to strangers. Most conversations were recorded

in stereo with head-mounted microphones; one was a telephone conversation.

3.2 Looking at a Wide Variety of Items

Given this corpus, the first thing to do was to identify all the non-lexical items. To avoid

missing anything that might be relevant, the intial definition was made inclusive. Specifically,

all sounds which were not laughter and not words were labeled as non-lexical items. A ‘word’

was considered to be a sound having 1. a clear meaning, 2. the ability to participate in

syntactic constructions, and 3. a phonotactically normal pronunciation. For example, uh-huh

is not a word since it has no referential meaning, has no syntactic affinities, and has salient

breathiness. Although the distinction between words and non-lexical items is not clear-cut,

as will be seen, this gave a reasonable way to pick out an initial set of sounds to examine.

To keep the scope manageable, attention was limited to sounds which seemed at least in

part directed at the interlocutor, rather than being purely self-directed, even if the commu-

nicative significance was not clear. This ruled out stutters and inbreaths.

The corpus has 316 non-lexical items, with one occurring about every 5 seconds on

average.

7

3.3 Listening to the Data

Rather than working from transcripts, all analysis was done by listening. This probably

helped focus attention on the interpersonal asp ects of the dialogs, rather than the information

content. This research style was facilitated by the use of a special-purpose software tool for

the analysis of conversational phenomena, didi (Ward 2003).

However, it being important to pay attention to the detailed sounds of non-lexical items,

these were labeled phonetically. These labels were always visible while listening.

The phonetic labeling was done using normal English orthography, as discussed below. IPA

was not used as it provides more detail than was needed, potentially obscuring generalizations.

This is a common choice in studying dialog, for example Trager (1958) argued that the

study of ‘vocal segregates’ such as uh-uh, uh-huh, and uh, requires ‘less fine-grained’ phonetic

descriptions. The labels in the corpus included annotations regarding prosody and voice,

although this information is not shown in this paper except where relevant. The labels in the

corpus are as seen in Table 1.

Due to concern that native knowledge of English or theoretical predilections might bias

phonetic judgments, about half of the items, including all difficult cases, were labeled inde-

pendently or cross-checked by an advanced phonetics student with little experience of con-

versational English and no knowledge of the hypotheses presented below. However no biases

were found, and the remaining items were labeled by the author alone.

3.4 Comparsion to Alternative Approaches

Thus the approach taken is unusual, even unique. Further, as will be seen in Section 5, it relies

in part on subjective judgements. Although there are better established and more powerful

methods, as well as helpful theoretical frameworks, none of these are quite appropriate for the

task of attaining an integrative account of non-lexical items. Thus the approach taken here.

4 A MODEL OF THE PHONOLOGY

Revisiting Table 1, the variety of non-lexical items is striking. Phonological conditioning, a

common cause of phonetic variety, can provide little explanatory power here, since these items

8

mostly

occur in isolation. This section shows how most of the variation can be accounted for

by a relatively simple model.

4.1 Intuitions about Non-lexical Expressions

Not only is the variety great, the set of possible sounds in these roles appears not to b e finite.

For example, it would not be surprising at all to hear the sound hm-ha-hn in conversation, or

mm-ha-an,orhm-haun and so on. However, there are limits: not every possible non-lexical

sound seems likely to be used in conversation. For example ziflug would seem a surprising

novelty, and would be downright weird in any of the functional positions typical for non-lexical

items. The existence of this intuition — that only certain non-lexical sounds are plausible in

conversation — is a puzzle that has not previously been addressed.

There have, of course, been attempts to describe the phonetics of such items by identify-

ing all possible phonetic components (Trager 1958; Poyatos 1975). However the descriptive

systems produced by these efforts cover wider ranges of sounds, including moans, cries and

belches, and so they do not help with the task of circumscribing the set of conversational

non-lexical items.

It is also possible to attempt to describe the set of possible items in terms of a list.

Although it is possible, for purposes of linguistic theory, to postulate the existence of such a

list, actually making one is problematic. The best attempts so far have been by researchers

who are labeling corpora for training speech recognizers, who of course have an immediate

practical need for some characterization of these sounds. For example, the best current

labeling of the largest conversation corpus, Switchboard, uses a scheme (Hamaker et al. 1998)

which specifies that hesitations be represented with one of uh, ah, um, hm and huh; that

‘yes/no sounds’ be represented with one of uh-huh, um-hum, huh-uh or hum-um ‘for anything

remotely resembling these sounds’; and that ‘non-speech sounds during conversations’ be

represented with one of: ‘laughter’, ‘noise’ and ‘vocalized-noise’. Comparison with Table 1

reveals how much information is lost by using such a list. Moreover, no mere list can account

for intuitions about which sounds are plausible: a description in terms of a list of 10 or 100

items gives no explanation for why hum-ha-hn, but not ziflug, could be the 11th or 101st

observed token. Of course a list-based model could be embellished with descriptions of the

permitted phonetic variations or sub-forms — as in Bolinger’s discussion which starts with

9

the

claim that ‘Huh, hunh, hm is [sic] our most versatile interjection’, and then turns around

and focuses on differences between these three forms. However such a hybrid approach seems

unlikely to be concise or to have much explanatory power. Thus a satisfactory list-based

account of conversational non-lexical items seems likely to be elusive.

4.2 The Phonetic Components

I propose that many non-lexical utterances in American English are formed compositionally

from phonetic components (leaving open the vexed question of whether these components are

phonemes or features (Marslen-Wilson & Warren 1994)). This claim is not without precedent:

there are a number of works which have, more or less indep endently, attempted to characterize

variation in non-lexical expressions in German, Japanese, and Swedish, and have done so

using tables of non-lexical items or lists of rules relating or distinguishing different tokens

(Ehlich 1986; Werner 1991; Takubo 1994; Takubo & Kinsui 1997; Kawamori et al. 1995;

Shinozaki & Abe 1997; Ward 1998; Allwood & Ahlsen 1999). These all imply the possibility

of an analysis in terms of component sounds.

This subsection describes the main inventory of phonetic components in non-lexical con-

versational sounds in American English.

• Schwa is often present, as seen in uh and uh-huh. (In conversation this is a schwa,

although when stressed, in tokens produced in citation form, it appears as ∧.)

• An /a/ vowel can also be present, as seen in ah, which is distinct from schwa, at least

for some speakers.

• An /o/ vowel occurs in some sounds, such as oh.

• An /e/ vowel occurs in yeah and occasionally elsewhere.

• /n/ and nasalization, of vowels or of the semivowel /j/, is a feature that can be present

or absent, as seen in uh-hn (versus uh-huh), in uun (versus uh), in nyeah (versus yeah).

• /m/ can occur in isolation (mm) or as a component, as in um (versus uh), hm (versus

huh)ormyeah (versus yeah).

• /j/ occurs initially in yeah and variants thereof.

10

•

/h/ occurs in isolation occasionally, as a noisy exhalation or a sigh. /h/ or breathiness

is also present in items such as hm (versus mm), and in the back-channel uh-huh. Some

such items involve breathiness throughout, others involve a consonantal /h/, while others

are ambiguous between these two realizations.

• Tongue clicks occur often in isolation, and occasionally initially. (Specifically, there are

cases where the click is followed by a voiced sound with no noticeable pause; the delay

from the onset of the click to the onset of voicing ranged from 50 milliseconds to 170

milliseconds in the corpus for these cases.)

• Creaky voice (vocal fry) occurs often , including for example on aummm, yeah, okay,

um, hm, aa. Creakiness sometimes spans the entire sound, but other times is present

only towards the end.

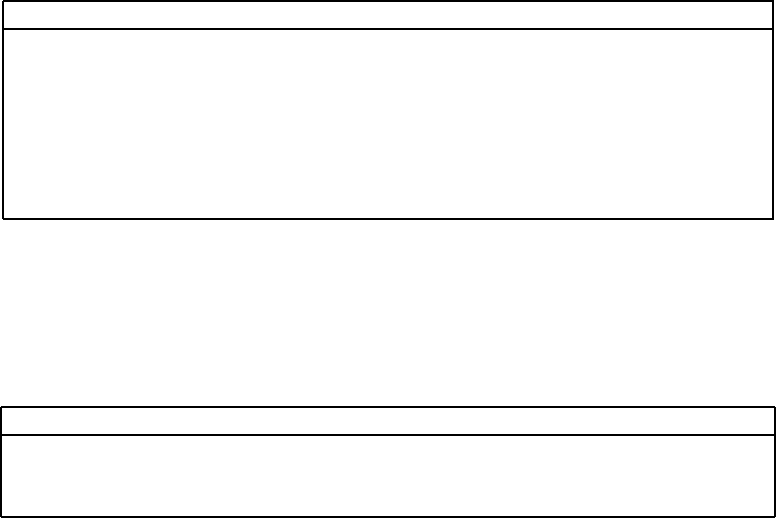

Sound Notes

/

ppppppp

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

pp

p

p

p

p

p

/

/o/

/a/

/e/ limited distribution

nasalization

/m/

/j/ limited distribution

/h/ and breathiness

click limited distribution

creakiness

Table 3: Phonetic Components of Common Non-Lexical Utterances.

The list above is summarized in Table 3. Although this summary may suggest that these

phonetic qualities are binary, for example nasalization being either present or absent, it seems

likely that the phonetic components are in fact non-categorical, involving ‘gradual, rather

than binary, oppositional character’ (Jakobson & Waugh 1979). This is an issue especially

for vowels, however investigating it is beyond the scope of this paper.

For expository convenience, this phonological analysis is given here, before the semantic

analysis, although in fact the set of relevant component sounds cannot be determined without

reference to meaning. Actually a preliminary version of the semantic investigations described

11

b

elow was done before the list of sound components was drawn up. This is why, for example,

the inventory of sounds groups together consonantal /h/ and breathiness, but not the nasals

/m/ and /n/: the first grouping, but not the second, has a consistent meaning, as will be

seen.

The fact that this inventory of sounds is fairly small makes it possible to concisely specify

the phonetic values for all the lab els seen in Table 1. Thus the non-obvious American English

orthographic conventions for non-lexical items are (slightly regularized) as summarized in

Table 4. Other Englishes apparently have other conventions, for example, British English

uses er to represent a sound not unlike American English uh (Biber et al. 1999). Further

discussion of spelling appears elsewhere (Ward 2000b).

notation phonetic value notes

h a single syllable-final ‘h’ bears no phonetic value,

elsewhere ‘h’ indicates /h/ or breathiness

n nasalization and /n/

click alveolar tongue click

u

ppppppp

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

uu as a syllable, indicates a short creaky or glottalized schwa

repetition of a letter duration and/or multiple weakly-separated syllables

- (hyphen) a fairly strong boundary between syllables or words

yeah /je

ppppppp

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

pp

p

p

p

p

p

/

kay /keI/, as in okay etc.

gh velar fricative rare

chh palatal fricative rare

oop /up/ rare

Table 4: Some Non-Obvious Facts about Conventional American English Orthography for

Non-Lexical Sounds

4.3 Rules for Combining Phonetic Components

The full phonological model includes the above list of component sounds plus two rules for

combining them.

The first way in which sounds are combined is by superposition. For example, a sound

can be a schwa that is simultaneously also nasal and creaky.

The second way is concatenation. There are probably minor constraints on this, for

12

example

/j/ and /e/ have very limited distributions, and click seems to appear only initially.

These remain to be worked out.

There seems to be a tendency for these sounds to have relatively few components, that

is, the number of component sounds in a non-lexical token generally is less than the average

number of phonemes in a word. There is also a tendency, rather stronger, for the number of

different sounds to be few: most sounds have only one or two, and more than three is rare.

This is also seen in the fact that these sounds often involve repetition.

4.4 The Power of the Phonological Model

The above components and rules constitute a simple, first-pass model of the phonology of

these sounds. Ideally a model should generate all and only the non-lexical utterances of

English.

As far as generating only non-lexical items, the model does reasonably well. The key

explanatory factor is that the inventory of component sounds excludes most of the phonemes

present in lexical items, including high vowels, plosives, and most fricatives. This provides

a partial explanation for native speakers’ intuitions that only certain sounds are plausible as

non-lexical items in conversation. However this model does overgenerate somewhat; although

Section 7.3 explains how it can be extended to reduce this.

As far as generating all the non-lexical items, this model does fairly well on this also.

Evaluating it against the inventory of grunts in the corpus, the phonological model accounts

for 91% (=286/316). It achieves this performance because, of course, it includes sound compo-

nents not present in English lexical items. However it does not account for all the non-lexical

items. The exceptions fall into 4 categories. First, there are 3 breath noises such as throat-

clearings and noisy inhalations. Second there 2 exclamations including rare sounds, namely

achh and yegh. Third, there are 5 items which only seem explicable as word fragments, ex-

treme reductions or dialectal items, such as i, nu and yei. Finally, there are 20 tokens with

phonemes missing from the model but normal for lexical English, including okay and wow.

This last set includes items which are only marginally non-lexical, in the sense discussed in

Section 10.2, so it is not entirely surprising that the model fails to handle them poorly.

Thus, although the model is not perfect, it accounts for rare non-lexical tokens and the

common ones in the same way. It is also more parsimonious and explains intuitions better

13

than

the alternative, modeling these items with a list of fixed forms. In this sense, these

sounds are truly non-lexical. Using this model as a base, subsequent sections extend the

analysis to deal with meaning and dialog roles.

5 METHODS FOR FINDING SOUND-MEANING CORRE-

SPONDENCES

Thus it seems that these sounds can be analyzed in terms of the composition of phonetic

components. This leads inevitably to the question: what do they mean? This is the topic of

this section.

Investigating the meanings of sound components is not without precedent. Various studies

in sound symbolism have found a rich vein of sound-meaning mappings, often productive in

non-lexical items but also infusing large portions of the lexicon (Sapir 1929; Hinton et al. 1994;

Magnus 2000). The specific mappings found, however, relate mostly to percepts — including

sounds, smells, tastes, feels, shapes, spatial configurations, and manners of motion — and do

not seem to be present in conversational non-lexical items.

Jakobson and Waugh (1979), Ameka (1992), and Wharton (2003) have noted that sound

symbolism may also be present in interjections.

Bolinger (1989), in his discussion of exclamations and interjections, proposed specific

meanings for vowel height, vowel rounding, and various prosodic features in a variety of

non-lexical items, as detailed below. The present paper proposes meanings for additional

phonetic features.

Nenova et al. (2001) examined various non-lexical items in a corpus of transcripts of task-

oriented dialogs. Based on considerations of articulatory effort, they proposed a distinction

between ‘marked’ items, those which involve nonsonorants, lengthening, multiple syllables or

rounded, noncentral or tense vowels, and ‘unmarked’ items, those which are composed of only

/m/ and /

ppppppp

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

p

pp

p

p

p

p

p

/. They showed that marked items are more common as indicators of ‘dynamic

participation’, as opp osed to the production of neutral back-channels during passive listening.

The present paper refines their analysis by ascribing specific meanings to specific sounds.

The analysis methods used in this paper combine and extend the methods used in these

studies. Detailed discussion of the methodological issues appears after an example of the

14

analysis.

5.1 A first example: /m/

In fillers, /m/ generally occurs while the speaker is trying to decide whether to speak or

trying to decide what to say. This is illustrated in Example 1, where the umm occurs before

a substantial pause preceding a restart of the explanation, in contrast to the uh, which occurs

before minor formulation difficulties. Clark and Fox Tree (2002) and Barr (2001) present

evidence that uh indicates a minor delay and um a major delay. (Althought perhaps only

speakers, not listeners, make this distinction (Brennan & Williams 1995; Barr 2001).) Also

Smith and Clark (1993) have observed, in the context of quizzes, that fillers um and am,

compared to uh and ah, generally seem to indicate more thought. Also, the distributions of

uh, um and umm in Table 2 show that the presence of /m/ correlates with the tendency to

appear as a filler, utterance-initial, rather than as a simple disfluency.

(discussing effects of speaking rate on phonology probabilities)

E: going to be different than if they’re, uh, talking much more slowly, 1

X: um-hm 2

E: so, umm [3 second pause] so, uh, the stuff that we did at . . . 3

(1)

This meaning for /m/ is seen in back-channels also. The contemplation can be directed

at various things, including trying to understand what the interlocutor is saying, trying to

empathize with him, or trying to evaluate the truth or relevance of his statement. For example,

in Example 2 M seems to be giving some thought to the situation X has related; specifically,

he seems to be sympathizing and perhaps contemplating the complexity or inevitability of

the situation. As a consequence, this mmm functions as a polite response, and in contrast to

a neutral uh-huh, which would trivialize the matter, and be rude.

(after some talk about television, children, and violent play )

X: and this video was about Ultraman . . . most of it’s not too violent

. . . but there is a little bit of stabbing and stuff

1

M: right 2

X: and so he came home and he was stabbing poor little Henry 3

M: nyaa-haao 4

X: yeah, I, I felt. 5

M: mmm 6

X: well, I mean, yeah. <click>I was pretty annoyed. 7

(2)

15

A

similar case is seen in Example 3, where T is telling a story, and has just introduced the

people involved. O’s m-hm seems to indicate that he’s thinking, perhaps trying to visualize

the complex situation described or perhaps speculating about what happened next.

(T is halfway into a story involving himself, his son, and his daughter)

T: my son was working in Bo-, uh, Boston, actually Cambridge, at the

time

1

O: m-hm 2

(3)

This can be contrasted with the /m/-less version, uh-huh, in Example 4, where O responds

to a simple utterance whose point and relevance is immediately obvious.

(T and O have just donned head-mounted microphones for recording)

T: once had to wear one of these riding in the back seat of an airplane,

because the airplane was so noisy

1

O: uh-huh 2

T: that the only way the four people in it could talk, was with earmuff

earphones

3

(4)

In general, the meaning of /m/ in non-lexical conversational sounds can be described as

follows.

Thought-worthy. People in conversation sometimes interact relatively superficially

and sometimes at a deeper level. Deeper places in conversation sometimes involve the

sharing of some emotion, but more often just the communication of something that

requires thought. The speaker may mark something said by the other as meriting

thought, or he may mark something that he himself has just said, or is trying

to say, as involving or meriting thought. This may correlate with the intention

or need to slow down the pace of the conversation in order to give time for this

thought or contemplation. Note that deepness in this sense does not usually involve

intellectually deep thinking, just that the conversation turns relatively deeper for a

moment or two.

Of the 57 tokens in the corpus containing /m/, 49 appeared to be indicating this sort of

meaning, and 8 seemed not to

5.2 Identifying Meanings for Sounds

The first methodological issue to discuss is that of how to discover and demonstrate that some

component sound S has some specific meaning M. While there exist good methods for testing

a hypothesized S (Magnus 2000), here the primary task is to discover the S in the first place.

16

One

basic strategy is to seek an M is shared by all (or most) tokens which include S. This

is the first basic strategy employed in this paper. This can be done using direct evidence for

the presence of meaning M in each case, or indirect evidence, such as the prevalence of S in

tokens serving functional or positional roles which correlate with M.

However this is not easy, because every utterance means many things at many levels

(Schiffrin 1987; Traum 2000; Louwerse & Mitchell 2003). For example, the umm in Example

1, which was presented as indicating that the speaker was thinking, might also be interpreted

as meaning that he was withdrawing, or becoming serious, or wanting to slow the pace of the

interaction, or foreshadowing the imminent discussion of something significant, or showing

a polite reluctance to dominate the conversation, or cuing the other to listen closely, or

holding the floor, or hiding something, and so on. In past, sophisticated studies of some such

functions at various levels have been done, and there are a number of useful frameworks for

analysis. These, however, are mostly limited in that they focus on one level or one type of

function. There are, for example, studies which consider some non-lexical items as discourse

particles, connectors, acknowledgements, continuers, assessments, turn-taking cues, and so

on. However, as Fischer (2000) notes, these items ‘actually form a more homogeneous group

than suggested by the number of different descriptive labels’. For this reason the analysis

here was not done within any specific theory or framework; rather the shared meanings were

sought bottom-up, by observing similarities across the corpus.

The task of the analyst is to examine the entire set of tokens containing S, and pick out

the ‘best’ meaning, that is, the meaning component M which is (most) common across the

set. While examining the data various possible Ms were kept constantly in mind, namely

those identified as important in previous studies of conversation, non-verbal communication,

and inter-personal interaction. These include various functions involving discourse structure

marking, signaling of turn-taking intentions, negotiating agreement, signaling recognition and

comprehension, managing interpersonal relations such as control and affiliation, and express-

ing emotion, attitude, and affect.

For lack of a formal procedure for finding the best M, the method used was to simply

consider various possible Ms and see how well each matched the set of tokens which include

S. This time-intensive process was simplified somewhat by homemade tools to help find and

quickly listen to all tokens sharing some phonetic property or semantic annotation. The

17

Ms

presented in this article are the result of iterative refinement to minimize the number of

exceptions and simultaneously avoid unnecessary vagueness. However there is no guarantee

that these Ms are in any sense optimal.

The second basic strategy for determining that S means M is to find a minimal pair of

non-lexical tokens, one with S present and one with S absent, and show that the difference in

meaning is M. Sometimes minimal pairs or near minimal pairs were found in the corpus; if

not, sometimes it is possible to appeal to intuition, considering what it would mean if some

non-lexical utterance in the corpus had occurred instead with some component S added or

subtracted.

Fortunately, for each of the component sounds studied, except schwa, evidence of both

kinds (shared meaning across the set and difference in a minimal pair) was found, and both

types of evidence pointed to the same meaning M in each case.

5.3 Determining the Meanings of Tokens

Identification of the meaning of a component sound using the methods above relies heavily on

the ability to identify the meaning of a non-lexical utterance as a whole. This also is not trivial.

Two basic sorts of information are available. The first is the context, primarily the nearby

utterances of the sp eaker and the nearby utterances of the interlocutor, both before and after

the token: from this it is generally possible to infer how the speaker meant it and/or how

the listener interpreted it. While these are not invariably aligned, as misunderstandings and

willful misinterpretations do occur, such cases are rare, and in the corpus all non-lexical sounds

appeared to be interpreted compatibly by both speaker and listener. (Although ultimately

a full understanding will require consideration of non-obvious differences in the information

content of such items to speakers versus listeners (Nicholson et al. 2003; Brennan & Schober

2001; Corley & Hartsuiker 2003).) The second sort of information is the way that the utterance

sounds in itself, based on native speaker intuitions. For this study, meanings are ascribed to

non-lexical sounds only if both types of information are available and consistent.

This means that tokens for which only one sort of information is available, or where the

two sorts of information are in conflict, are not ascribed meanings; they are characterized

below as unclear in meaning. For example, in three of the tokens including /m/, the

token itself, considered in isolation, does appear to be contemplative, but the context does

18

not

suggest any need for the speaker to be thinking, as in myeah in Example 24. (Perhaps

the speaker in these cases had a private thought, not related to the conversation, or perhaps

he was momentarily distracted, producing an utterance that was not strictly appropriate for

the context. As it happens these 3 cases were all back-channels, where lapses of attention can

often pass unnoticed.) For lack of a technique for further investigating such examples, such

non-lexical utterances are simply considered to be unclear in meaning and thus providing no

evidence for or against any sound-meaning correspondence.

It is worth stressing that both sorts of information are subjective, especially the second.

There are alternative research methods which minimize or eliminate subjectivity, for example,

controlled psychological experimentation, acoustical analysis, Conversation Analysis, statis-

tical analysis over large corpora, and validation with labels by analysts unfamiliar with the

hypotheses. All of these methods are superior in various ways to the current methods, and

ultimately the claims made here will stand or fall as they are supported or rejected by more

powerful methods. However for the present purpose, identifying meanings in the first place,

the sorts of information given by simple approaches are adequate.

Another complication for this approach is that patterns of usage of non-lexical sounds

vary across communities. It is well known that the timing and frequency of non-lexical usage

varies with ethnicity, region, and gender (Erickson 1979; Tannen 1990; Mulac et al. 1998), and

the meanings ascribed to non-lexical tokens almost certainly do also. While such differences

are interesting sociolinguistically, for present purposes they raise a difficulty: there will be

examples where the interpretation presented here will not be shared by all readers. As a

partial back-up, all of the claims in the next section are multiply supported, so that none is

dependent on the interpretation of a single example.

Since subjective interpretations are unavoidably involved, the main purpose of the dialog

excerpts is to allow the reader engage his or her own intuitions, rather than, say, to support

tight demonstrations that each token must mean what is claimed. Thus the dialog excerpts

are presented concisely and in standard orthography and punctuation, although of course

there exist alternative conventions which are more descriptive in terms of phonetics, prosody,

timing, etc. (Edwards & Lampert 1993; Hutchby & Wooffitt 1999; Jefferson 2002). Concise

presentation is necessary for another reason also: given the goal of an integrated account

and the concomitant need to examine a large number of tokens, space does not permit an

19

exhaustiv

e presentation of any single example.

It is not uncommon for people looking at a non-lexical item to have different interpre-

tations. In my experience most such differences arise not from dialect differences or funda-

mentally different judgments, but rather from noticing different aspects of the dialog; this is

the problem of multiple levels mentioned in the previous subsection. Such different interpre-

tations generally turn out to be compatible. Differing interpretations are easier to resolve if

the audio itself is available. To give more readers access to this data, sound waves for the

non-lexical items discussed, with timing, pitch and energy information for the utterances in

the contexts, are available at the website for this paper, http://nigelward.com/egrunts/,

mirrored at http://www.cs.utep.edu/nigel/egrunts/.

5.4 Using the Compositional Hypotheses

These analysis methods presume that the meaning of each component sound is evident in the

meaning of the whole, or, more strongly, that the meaning of each non-lexical utterance is

compositional. This is the Compositional Hypothesis. Its validity will be discussed later, but

for now it is an working hypothesis, and an essential one, since it makes the investigation

possible.

This hypothesis makes analysis possible but not easy. In particular, the hypothesis implies

that the meaning contributions of all sounds in the token are also active, in addition to the

meaning for the sound under study. Thus contributions of some sounds may be more salient.

For this reason careful listening is required, to detect not only the obvious meanings but also

the more subtle ones.

This is especially true for prosodic features, which often seem to be trump cards, dom-

inating other contributions to the perceived meaning (although Bolinger (1989) probably

overstates the case with the suggestion, with reference to huh, hunh, and hm, that ‘prosody

is fairly decisive, in fact this interjection might almost be regarded as a mere intonation car-

rier’.) Fortunately, highly expressive non-lexical utterances, with complex contours carrying

complex meanings (Luthy 1983), were rare in this corpus. Indeed, almost all tokens had an

almost flat pitch, so this was not a big problem in practice. Prosody is discussed further in

Section 8.

The Compositional Hypothesis also implies that the sound-meaning mappings are context-

20

indep

endent: that each sound bears the same meaning regardless of the context. This may

not be completely true, for both phonetic context and discourse context. First, it is possible

that the contribution of one sound could be masked or shifted by the meaning contributions

of neighboring sounds. Second it is clear that the discourse context affects interpretations;

this will be discussed in Section 7.4.

6 SOUND-MEANING CORRESPONDENCES

Having already a meaning for /m/, this section lo oks at the other common sound components.

6.1 Nasalization and /n/

(C has applied for a summer-abroad program)

H: I bet you’ll hear something soon. 1

C: I hope so. I just turned that in, though, like. A couple weeks ago, so. 2

H: yeah (slightly creaky) 3

C: you know what I mean, so 4

H: yeah, it might take a little longer 5

C: nn-hn 6

(5)

In Example 5 C’s nn-hn seems to indicate that C had held this opinion all along; it

effectively closes out this topic. Had the sound been uh-huh, without nasalization, it would

instead imply that somehow H had offered new information, and leave open the possibility of

more talk on this topic. Other nasalized versions, such as uh-hnn would, however, share the

same meaning component seen in nn-hn.

(A is illustrating the difficulty of working with the International Phonetic Alphabet)

A: she had to count them by hand from the print-out, because she didn’t

have any way of searching for these weird control characters

1

J: nyeah-nyeah (low flat pitch, overlapping as A keeps talking) 2

A: now I mean she could have gotten something that might have been able

to do it, but

3

J: (interrupting) It’s a pain, yeah 4

(6)

Similarly in Example 6, which occurs a minute after J had mentioned a problem of using

the IPA for corpus work, the nyeah-nyeah

1

seems to be serving to remind A of this, that she

is already well aware of such difficulties, and by implication encouraging closure of this topic.

1

not to be confused with the nyah-nyah of playground taunts, which is creaky, has a low vowel, and has a

downstep in pitch

21

An

unnasalized yeah-yeah (in the same flat pitch) here would sound merely bored, without

laying claim to prior knowledge.

The nyaa-haao back in Example 2 line 4 is slightly different. In this case the fact which

it reacts to has not been previously mentioned explicitly, but it is nevertheless obvious —

from the previous context it is clear where the story is leading, and when X finally gets to

the point, it seems that M has already seen it coming, as indicated by this nasalized token.

Nasalized non-lexical sounds generally mean not just that that the speaker has pre-

knowledge of something, but that the something is already established, and known to the

interlocutor too. (This ‘pre-knowledge’ is related to the notions of ‘old information’, ‘given

information’ and ‘common ground’, but is often based on extra-linguistic knowledge.)

In Example 7, V’s nn-nnn conveys not only a negative answer

2

but also that V is surprised

by the question, probably because he considers that M should have already known the answer,

to the extent that his statement that he slept for most of the train ride implies that he expe-

rienced no problems. A similar usage is probably also present in the examples of Jefferson’s

(1978) study, in which she characterizes 3 nasalized tokens, ne:uh, nyem, and mnuh, occurring

in response to questions, as indicating that the person who asked the question already ‘knows

the answer’ or should be able to infer it easily.

(at the start of a recording session M throws out a first topic)

M: So, V, tell me, tell me what you saw on the train, that, because I slept

for an hour in be-, sort of in the middle

1

V: well, I slept, I slept for most of the train ride, actually. The one up

here?

2

M: yeah 3

V: the Tokyo, the Tokyo, train ride, the Shinkansen 4

M: so, did you have a problem with your ears popping? 5

V: nn-nnn. You did? 6

M: Yeah, I did, actually . . . 7

(7)

Nasalization and /n/ often seem to signal the following function:

2

probably due to the 44-22 pitch contour with a sharp downstep and a glottal stop

22

Covering Old Ground. Conversations often re-cover old ground: things that came

up earlier get repeated or referred back to. While this may involve literal repetition,

it may just be the expression of things that are obvious or redundant since inferable

from what has gone before. People sometimes indicate it when they are expressing

something that is somehow covering old ground, or to indicate that they think the

other person is doing this, whether deliberately or inadvertently.

Of the 20 occurrences of nasalized non-lexical items in the corpus, 12 seem to mark the

covering of old ground or expression of information already known. Of these, 11 were in

reference to something said by the other person (7 after a restatement of something that had

already surfaced in the conversation or was otherwise obvious, and 4 after the other p erson

has said something that the speaker could have predicted or seems to consider well-known).

1 occurs after the speaker himself has said something that he appears to consider well known,

as part of an apparent bid to close out the topic. There are 4 cases which seem to lack any

meaning of pre-knowledge

3

. 4 cases are unclear in meaning

4

.

6.2 Breathiness and /h/

hmm, unlike um and mm, occurs only as a back-channel. Moreover, hmm, compared to mm,

seems to be bearing some extra respect and expressing a willingness to not only listen, but

to give the other person’s words some weight. A correlation with deference is also seen by

the fact that hmm, hm and mm-hm tend to be produced by lower-status speakers: in the 3

conversations in the corpus where the interlocutors were significantly unequal in age and social

status, 12 out of the 13 occurrences of these items were produced by the younger speaker.

Breathiness is also a factor distinguishing the agreeable uh-huh from the uh-uh of denial

5

.

/h/ being related to relative social status and functional role (back-channel versus filler),

it is hard to find clear minimal pairs, with and without breathiness, for the same speaker and

3

2 of these occur where the speaker is somewhat taken aback.

4

Of these, in 2 cases the sound itself, considered in isolation, does appear to connote a claim of pre-

knowledge, but it occurs in a context where it seems unlikely the speaker could really have already known the

information the interlocutor had just conveyed. Listening to the conversation after-the-fact, these items seem

slightly rude, making the speaker sound like a know-it-all. Given the context, however (all were back-channels,

all overlapped long continued speech by the interlocutor, and all occurred at times when the speaker seemed

uninterested in the topic), p erhaps meaning was merely ‘I already know as much about that topic as I want

to, so we can move on to another topic’. Under this interpretation there is a similarity to the already-known

meaning.

5

and is probably stronger than the other two factors: absence of glottal stop and final pitch rise

23

the

same functional role. Example 8 is a rare example: here the uhh, unlike O’s other fillers,

is breathy. This may be marking some trepidation, in that this occurs at the point where O,

for the first time in a long conversation with a senior person in his research field, ventures to

make a joke.

(after some talk on the merits of goats versus llamas as pack animals)

O: uu (creaky) they, they carry quite a bit, compared to their body

weight, um, . . . And uhh (breathy), if you bring a female goat you

can (pause) drink her milk and make yogurt and (pause) (laughs)

1

T: (laughs) 2

O: (pause) you don’t need to turn back, head back to town ever, you

know (laughing)

3

(8)

In Example 9, the huh (in falling pitch and of moderate duration) is a challenge, but it

is a polite one, an attempt to engage the other person in discussion, in contrast to the flat

contradiction which an uh would convey.

(X thinks that a reporter is biased)

X: and he always hypes everything up 1

M: wow 2

X: is what I’ve heard 3

M: huh, that isn’t the impression I’ve gotten 4

(9)

Concern. Sometimes people in conversation are lacking in confidence or somehow

dependent on the other person, and they sometimes signal this. While speaking,

they may be solicitous or tentative, as if fearing that the other person will find

their words stupid or inappropriate, and while listening, they may listen with extra

concern and attention. This often occurs when the other person is older or in a

position of power, but arises more generally at points in a conversation when one

person for a moment treats the other person’s words or thoughts with extra respect

or consideration.

Of the 43 tokens with /h/ or breathiness, 23 appear to bear a meaning of concern, deference

or engagement. Of the remainder, 9 were two-syllable sounds which would have seemed rude

had breathiness not been present. There were also 3 cases which were borderline laughter, 2

sighs, and 1 where the breathiness seemed to soften a contradiction.

24

6.3 Creaky Voice

(discussing who is likely to be at the party )

H: and, um, and that other guy, K, majoring in Psychology. 1

C: yeah(creaky). (two second pause) yeah, they’re so fun. 2

H: (pause) That’s cool 3

C: yeah 4

(10)

In Example 10 C’s first yeah offers confirmation of a factual matter, in response to H’s

uncertain-sounding statement of what she thinks K’s major is. The subsequent yeahs relate to

subjective impressions. Perceptually the first yeah sounds authoritative and the others do not.

The most salient phonetic difference is creakiness. This can be considered as indicating a sort

of detachment in the sense that C’s creaky response is not merely a polite acknowledgment

of H’s statement for the sake of continuing the conversation, but reflects that C is stepping

back and providing an evaluation of H’s statement based on C’s independent knowledge.

(talking at a conference, resuming after an interruption )

R: let’s see, so we were talking about what my favorite 1

X: yeah 2

R: talks were. Um, actually right now I’m sort of interested in what this

U-tree algorithm is, because

3

X: yeah 4

R: I’ve done a, um (creaky), a search, or, a literature search a while

back on, on reinforcement learning and . . .

5

(11)

Similarly, in Example 11 R’s second um is creaky; at that point R is about to reveal that

he is somewhat of an authority on the topic of learning algorithms, not merely chatting about

them to politely pass the time. His first um was not creaky, and, as a statement of personal

taste, would have sounded strange if it were.

(T is driving, O is navigating)

T: shall I just go in here and turn around, n (and) 1

O: yyyeah. Yeah (creaky), that might be best 2

(12)

Example 12 has a pair where the first yeah is uncertain, and the second, creaky one,

produced after due deliberation, sounds authoritative.

25

(discussing whether it would be fun to go to the beach)

H: I want it to be sunny 1

C: I know, this weather is no good 2

H: No, it makes me like groggy, kind of, you know what I mean, like 3

C: like you want to stay in bed and 4

H: yeah (slightly creaky) 5

C: just like watch a movie or something 6

H: and like not really do anything 7

C: yeah (very creaky) I know. I’m trying to fight it (laughs) 8

(13)

In Example 13 H complains about the weather and how it affects her, but C then reveals

that she feels exactly the same way. Her yeah, being creaky, seems to indicate that C has

personal experience, indeed she seems to be taking a moment here to actually indulge in that

feeling. A non-creaky yeah would be less appropriate here, although it would be fine in an

expression of merely perfunctory sympathy.

Creak also has a possibly related function in which it occurs with items which indicate

detachment in the form of a momentary withdrawal to take stock of the situation. In Example

14 J infers that A’s mother was from North Germany, but A then corrects her. After A

clarifies the location of Wiesbaden, J talks to herself for a moment while he continues, then

she produces a creaky okay and then a normal yeah. It seems as if J is withdrawing from the

conversation to consult and correct her mental map of German dialects, and indicating this

with the creakiness of the yeah, before returning to full attention and participation with the

okay.

(regarding trills in German)

A: but I think my mother does the, ah, the uvular one all the time . . . 1

J: . . . your Mom’s from North? 2

A: no, she’s from ah Wiesbaden, which is uh 3

J: don’t know 4

A: in the central west; 5

J: mm 6

A: it’s right near Frankfurt, west of Frankfurt; 7

J: center, north, west, yeah (slightly creaky) okay 8

A: and ah, or she’s from that area, she’s actually from a small town . . . 9

(14)

The slightly creaky yeah back in Example 5 is another example of creakiness in response

to correction; H produces it after realizing that she had misunderstood the situation.

26

Claiming Authority. Although people sometimes say things lightly, other times

they really know what they are talking about. Thus some things people say in

conversation are intended as authoritative statements, advice, opinions, decisions,

recollections, etc., and often speakers will indicate that these are intended as such.

Authoritative statements may be based on expert knowledge of some topic, on direct

experience, and so on.

Of the 56 tokens in the corpus which were creaky or partially creaky, 38 seemed to indicate

authority

6

.

6.4 Click

The meaning of tongue clicks can be subsumed under the term personal dissatisfaction.

(C has suggested going to the beach; H responds by describing her homework assignments)

H: like I haven’t like corrected my paper, and re-printed it 1

C: <click>-oh (slightly breathy, low fairly flat pitch) 2

(15)

In Example 15, C’s click seems to be indicating dissatisfaction with the situation, namely

the fact that H can’t come, and perhaps dissatisfaction with H herself, in the form of a mild

remonstrance.

Some clicks seem to indicate dissatisfaction with the current topic, or the lack of one; these

uses often occur near topic change points. In Example 16, M produces clicks while searching

for a topic, before introducing a new topic, and when closing out a topic.

(M is trying to find a new topic at the start of the recording session)

M: aoo (creaky), let’s see what other exciting things have been, worth

chatting about. <click> uuuuuuu (creaky). (3 second pause)

<click> Really good low budget movie you might want to rent . . . (M

describes movie for 25 seconds, X seems uninterested) . . . <click> was

quite well done

1

X: (3 second pause) I’m probably not going to rent that any time soon,

because (changes topic)

2

(16)

6

Of the remainder, 5 back-channels seemed to indicate boredom, lack of interest, or impatience, 1 annoyance,

3 taking stock after being corrected by the other person, as in examples Example 5 and Example 14, and 1

occurred as the speaker (while driving) was executing a turn and apparently signaled concentration on that to

the exclusion of attention to the conversation.

27

The

click in Example 17 seems to express E’s dissatisfaction with his own performance as

a conversationalist, and marks the point where he gives up on one formulation and re-starts

his explanation on a new tack.

(E is trying to describe simply a highly technical line of research)

X: so, what are you doing, actually? 1

E: well, hhh-uuuh, at the moment I’m doing phonological modeling, and

essentially trying to get, umm (pause) <click> Trying to develop

models of

2

(17)

Dissatisfaction. People in conversation are sometimes momentarily unhappy but

then move on, and they often indicate when they do this. This momentary unhap-

piness can be about the conversation itself, as when the conversation hits a rough

spot, one runs out of things to talk about, or when one has a problem expressing

oneself fluently; or the unhappiness can be about the topic, as discussing something

of which one disapproves or finds disappointing.

Of the 26 clicks in the corpus, 19 seemed b e expressing some form of dissatisfaction. Of

these 9 seemed to express self-remonstrance, either at forgetting something, at getting off

track, or at explaining something poorly (these sometimes co-occurring with the close of a

digression or a re-start of an explanation on another tack), 4 seemed to indicate dissatisfaction

with the current topic, co-occurring with a bid to close it off. 3 seemed to express dissatisfac-

tion with the situation under discussion, and 3 seemed to be dissatisfaction directed to the

interlocutor, as a form of remonstrance

7

.

6.5 /o/

It is well known that the expression oh can mark the receipt of new information, among other

functions (Heritage 1984; Schiffrin 1987; Fox Tree & Shrock 1999; Fischer 2000), and this is

seen in the corpus too, as in Example 18. Other times it performs related functions, such as

indicating the successful identification of a referent introduced by the other sp eaker, and the

uptake of self-produced new information, as a result of figuring something out or noticing it.

7

Of the remainder, 5 seemed to simply mark the introduction of a new topic, and 1 marked a shift in

conversation style from serious to facetious.

28

(after X has explained that he is collecting conversation data)

E: is there any particular topic that we should, uh 1

X: no 2

E: oh.3

X: so 4

E: So it’s just 5

X: so, yeah 6

E: ookay 7

(18)

It is worth noting that the oh often occurs, not at the moment where the new information

is heard, but a fraction of a second later, after the information has been assimilated somewhat

and the listener has decided what stance to take regarding it, as seen in Example 19.

(regarding who buys Sailor Moon comic books in Japan)

X: there’s two audiences for that, one is the junior high school girls, and

the other is the pervert, the uh, the, the perverts

1

M: yeah, oh absolutely, yeah, yeah 2

(19)

okay seems to share with oh some element of meaning, as Beach (1993) has observed, and

this is likely due to the shared /o/. This is seen by the fact that the newness is downgraded in

cases where the /o/ is reduced to a schwa (ukay as in Example 23), elided completely (kay), or

replaced by a nasal (m-kay, n-kay, and unkay). On the other hand, where the newness of the

information is significant, the /o/ is lengthened or repeated, forming ookay (as in Example

18) or oh-okay.

New Information. People in conversation sometimes encounter information which is

new to them, and may signal that they are aware of, or want to draw attention to,

that newness. This may be done in reference to one’s own utterances or in reference

to the other’s utterances. The new information may have been introduced by the

other speaker, or may be self-produced, as a result of figuring something out or

noticing it. This new ‘information’ may also include a new topic or referent, or a

surprising turn of the conversation, etc.

Of the 46 tokens containing /o/, 44 bear a new-information meaning.

6.6 /a/

Sometimes people in conversation are passive or at a loss, and other times they are fully in

control and know exactly what they’re doing. /a/ seems to signal the latter: that the speaker

29

is

fully on top of the situation and ready to act

8

.

(X is winding up a roundabout explanation of why he’s recording conversations)

X: . . . when does it happen in English? is the question 1

E: right 2

X: and I have no data 3

E: ah (creaky), okay (slightly creaky) 4

(20)

In Example 20 the /a/ seems to indicate this. Indeed, it could be glossed as ‘I’ve got it, I

understand the whole picture, I’m very familiar with that kind of situation, I could finish your

story for you’. This is in contrast to an /o/, which would stress the novelty of the information

that X lacked data, and in contrast with schwa, which would imply that E was not sure what

to say, perhaps having failed to understand the statement or its significance.

(over dinner after a conference)

E: did you go to the talk? 1

X: which one? 2

E: did you go to my talk? I should say 3

X: I missed it, I’m sorry 4

E: ao (creaky) that’s fine, that’s fine. 5

(21)

A similar meaning is seen in Example 21, where ao, instead of oh, seems to connote that

E had half-expected X to have missed the talk, and is already prepared and willing to give

him the gist of it, as he then goes on to do.

A similar distinction between /a/ and schwa may be seen in fillers and disfluency markers.

ah seems to be used (for those speakers who use both uh and ah) in cases where the filled

pause is being produced mostly for the benefit of the listener. That is, /a/ occurs when the

speaker knows exactly what he wants to say, and the purpose of the filled pause is only to

give the listener time to re-orient or catch up. This is seen in the last line of Example 14,

where ah introduces a parenthetical remark, and in the third line of Example 14, where the

ah precedes code-switching from English pronunciation to German pronunciation.

8

This claim appears to conflict with Bolinger’s (1989) remark that ‘since the vowel is neutral, it fluctuates

nonsignificantly, easily verging on [o] or [a]’, but Bolinger was focusing on exclamations of surprise, which may

not follow the same rules as more conversational non-lexical utterances (Section 9.4).

30

In Control. Although sometimes people in conversation are momentarily passive

and drifting or at a loss, there are times when they are fully in control, knowing

exactly what to say or do next, and people in this state often indicate it. As a special

case, this is seen when a speaker is pausing, not because he’s stuck for how to say

something, but semi-deliberately to warn the listener that something complex, like

a borrowing from a foreign language is coming up.

This seems compatible with Fischer’s (2000) observation that ah, in comparison to oh,

‘does not diplay emotional content’ and indicates that ‘I want to say some more’.

Quantifying the strength of the association between /a/ and readiness to act is complicated

by the fact that some speakers use ah but not uh as a filler, and others always use aum but

not um. Thus for some speakers /a/ is perhaps a mere allophone, the variant of schwa used

in fillers and disfluency markers.

Of the 18 tokens in the corpus containing /a/, 9 seem to manifest some such meaning of

being in control, including 4 which preceded foreign language words.

6.7 Schwa

Schwa is the most common sound in non-lexical items in the corpus. It seems to be neutral,

bearing almost no information. This is seen in the stereotypical back-channel uh-huh, which

sometimes conveys essentially nothing but ‘I’m still here’, and in the stereotypical filler uh,

which often conveys almost nothing but ‘I’m starting to talk’.

This neutrality can be seen by contrasting schwa with /o/. Consider Example 22, where

the long oh indicates that B now understands why A is upset about having missed the meeting.

In contrast, a schwa-based sound, such as uh or uh-huh here would not indicate this at all.

(after some talk about a meeting that H feels bad about having missed)

H: and then, like, at the end you’re supposed to, like, split up into, like,

program groups, but.

1

C: ooooh 2

(22)

Similarly in Example 23, A acknowledges receipt of new information with okay, but pro-

duces ukays (with schwa) when he is acknowledging only the receipt of confirmation of what

he already knew.

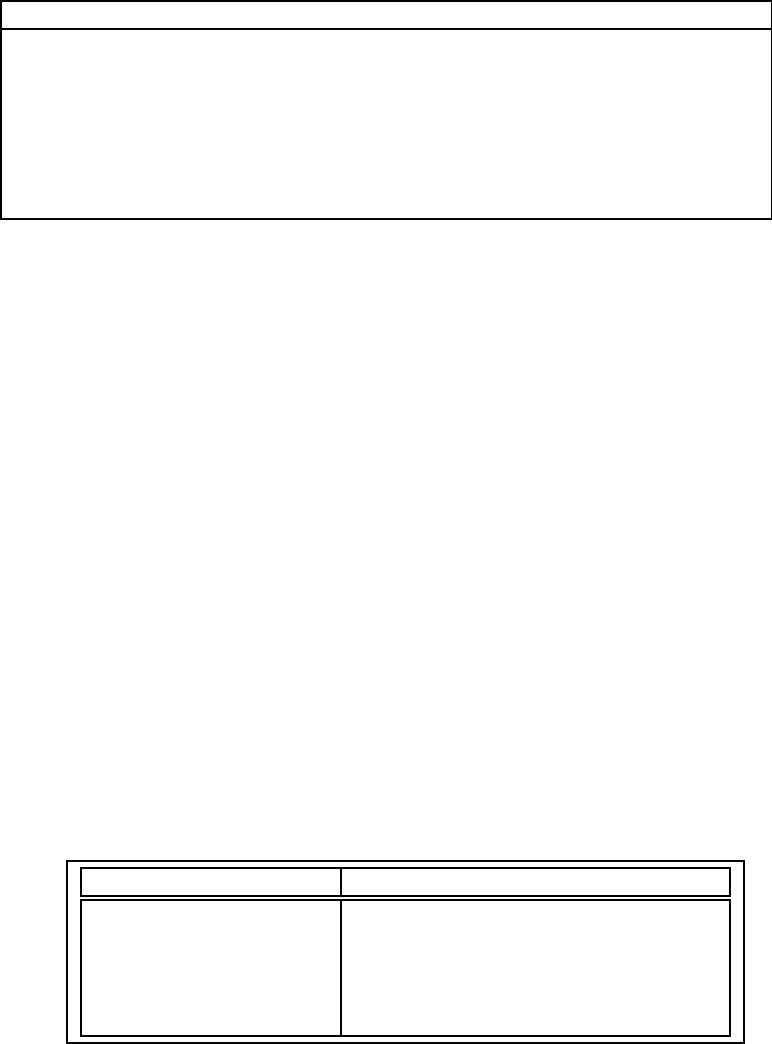

31

strength of support

sound meaning in corpus other

/m/ thought-worthy strong strong

nasalization covering old ground weak weak

/h/ and breathiness concern moderate –

creaky voice claiming authority moderate –

clicks dissatisfaction moderate –

/o/ new information strong weak

/a/ in control weak weak

/schwa/ neutral weak –

Table 5: Summary of the Meanings Conveyed by some Common Sound Components. De-

scriptions in the ‘meaning’ column are highly abbreviated.

(J is starting to describe an interesting conference talk)

J: she works at Bell Labs, and what they do is, they do diphone concate-

nation. okay

1

A: okay, yeah, now, that’s like the TrueTalk system, right? that’s the

AT&T one

2

J: iiyyeahh, 3

A: ukay 4

J: that’s AT&T, 5

A: ukay 6

J: yeah. So, um, basically they’re doing diphone concatenation and . . . 7

(23)

While there are minimal pairs with and without schwa, such as um and mm, there seems

to be no difference in the basic meaning; rather the versions with vowels just seem to express

the basic meaning more confidently, as one wold expect from the greater loudness (Section 8).

6.8 Summary of Correspondences

Thus there is a candidate for the meaning associated with most of the sound components

common in non-lexical utterances. These sound-meaning correspondences are summarized in

Table 5. Of the sound-meaning mappings identified, some are strong, obvious, and almost

invariant, some are fairly limited, weak, or tentative, and the others are in between, as seen

in the table.

It is worth noting that these sound-meaning correspondences show up even when working

under the assumptions of compositionality and context-independence, which are probably not

32

en

tirely correct.

Interestingly, some of the sound-meaning correspondences identified above for English

also appear to be present in Japanese (Ward 1998; Okamoto & Ward 2002; Ward & Okamoto

2003), raising the question of whether universal tendencies are at work.

At this point is is worth mentioning some other phonetic features that various researchers

have implicated in various meanings. Lip rounding may indicate surprise, and it has even been

suggested, for tokens indicating astonishment, that it is not tongue position but ‘the rounding

of oh, which distinguishes it from ah’ (Bolinger 1989). Glottal stops are often implicated with

a meaning of negation or denial. Vowel height may also be significant: ‘the ‘importance’ of

ah, for example, is consonant with the ‘size’ implication of the low vowels’ (Bolinger 1989).

Throat clearing has been observed to function as an indicator of upcoming speech (Poyatos

1993).

The sound-meaning correspondences provide answers for the second question posed in

the introduction: what all the variants mean. The existence of these correspondences also

answers the first question: the reason for the existence of so many variants is just that people

in conversation have a large variety of (combinations) of meanings that they need to express.

7 THE STRENGTH OF THE SOUND-MEANING CORRE-

SPONDENCES

This section discusses the strength of the proposed sound-meaning correspondences and the

power and limits of the compositional hypothesis.

7.1 Evaluation of the Compositional Hypothesis and the Compositional

Model

According to the compositional hypothesis, the meaning of a non-lexical utterance is pre-

dictable from the meaning of its component sounds. Although this was a useful working

hypothesis, it is clear that it is not invariably true, as witnessed by the exceptions noted

above. In some cases it is clear where compositionality fails. For example, examining the

properties of the four tokens which are exceptions to the correlation between /n/ and pre-

knowledge (Section 6.1), it turns out that two of these were the shortest of the all sounds

33

in

volving /n/, which suggests that somehow the lack of duration is canceling or overriding the

contribution of /n/. Also, very quiet sounds appear to convey little or no meaning, regardless

of their phonetic content.

It therefore is necessary to reject the Compositional Hypothesis as a full account.

However, since most non-lexical tokens in conversation seem to be largely compositional

in meaning, the idea is worth salvaging. I therefore propose a compositional model for

non-lexical conversational sounds, specifying that the meaning of a whole is the sum of the

meanings of the component sounds. Compared to the alternative, a list-based model which

associates meanings arbitrarily with fixed sequences of sounds, the compositional model ex-

plains the meanings of rare items as well as common ones, and does so parsimoniously. Thus,

in this sense also, these items are truly non-lexical.

Having seen that the compositional model is better than the alternative, it is of interest

to consider how well it does absolutely, so the rest of the section examines how much of the

corpus data is accounted for by the compositional model.

The power of the sound-meaning correspondences can be quantified by counting failures,

that is, cases where one or more predictions is not borne out. These were listed in Sections

5.1 and 6 for each sound, and summarized again in Table 6. Summing across all 316 tokens,

for 77 (24%) the model predicts some meaning element that is not found. In other words,