International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy 2003, Vol. 3, Nº 2, pp. 299-310

Application of the IPT in a Spanish Sample: Evaluation

of the “Social Perception Subprogramme”

Sonia García

*

, Inmaculada Fuentes*

1

, Juan Carlos Ruíz

*

, Elisa Gallach

**

and Volker Roder

***

*Universidad de Valencia, España. **Equipo de Salud Mental de Aldaia, Valencia, España.

***University of Berna, Switzerland.

1

Reprints may be obtained from the first author. Departamento de Personalidad, Evaluación y Tratamiento Psicológicos,

Facultad de Psicología, Avenida de Blasco Ibáñez 21, 46010 Valencia, España. E-mail: fuentesd@uv.es

ABSTRACT

This study analyses the impact of the second IPT subprogramme (Roder, Brenner, Hodel

& Kienzle, 1996) in chronic schizophrenic patients. The programme intends to improve

their ability to perceive and to interpret social situations. The sample was formed by 20

participants, divided into two groups: 11 in the therapy group and 9 in the control group.

Social and clinical measures have been used, as well as an instrument developed for the

assessment of Social Perception, as it is defined in the IPT. This instrument has been

sensitive to changes in the pre-treatment and post-treatment measures, showing that

schizophrenics patients have improved their ability to perceive and to interpret reality in

a more adequate way.

Key Words: Social Perception, Schizophrenia, Assessment, Psychosocial Intervention,

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy.

RESUMEN

Aplicación de la IPT en una muestra española: evaluación del "subprograma de percep-

ción social". Este estudio investiga los efectos del segundo subprograma de la IPT en

pacientes esquizofrénicos crónicos (Roder, Brenner, Hodel y Kienzle, 1996). El programa

pretende mejorar sus habilidades para percibir e interpretar situaciones sociales. La muestra

está formada por 20 participantes, divididos en dos grupos: 11 constituyen el grupo

experimental y 9 el grupo control. Se han utilizado medidas clínicas y sociales, así como

un instrumento desarrollado para la evaluación de la percepción social, tal y como es

trabajada en la IPT. Este instrumento se ha mostrado sensible a los cambios pre y post-

tratamiento, poniendo de manifiesto que los pacientes esquizofrénicos han mejorado sus

habilidades para percibir e interpretar la realidad de un modo más adecuado.

Palabras Clave: Percepción Social, Esquizofrenia, Evaluación, Intervención Psicosocial,

Terapia Cognitivo Conductual.

300

© Intern. Jour. Psych. Psychol. Ther.

S. GARCÍA, I. FUENTES, J. C. RUIZ, E. GALLACH, V. RODER.

People do not react to reality just as it is, but as they build or interpret it (Ibáñez,

1979). Only an adequate interpretation of the environment, physical and social, permits

our adaptation to it. For that reason, reality interpretation and the processes involved

in it should be important aspects to consider in the rehabilitation of mental patients.

Bedell & Lenox (1994) have studied the relation in the way we perceive reality and

how we behave in society. These authors think that the ability to perceive is an important

factor for a good social functioning. They consider that social abilities would include

two groups of skills: cognitive and behavioural. Social perception and information

processing are included in the cognitive skills group. Both of them define, organize and

guide social skills. On the other hand, behavioural skills refer to verbal and nonverbal

behaviour used in applying the action of a decision once cognitive processes have

finished.

In the late eighties, as a result of the investigations that related cognitive deficit

and social skills, it was concluded that schizophrenic patients had a deficit in social

perception. This was particularly true in the recognition of affects, which makes them

answer inadequately to other people (Halford & Hayes, 1991). Other deficit identified

besides facial affect recognition (Morrison, Bellack & Mueser, 1988; Bellack, Blanchard

& Mueser, 1996), and nonverbal perception (Toomey, Wallace, Corrigan, Schulderg &

Green, 1997), has been inapropiate situational stimulus perception (Corrigan & Green,

1993).

In relation with facial affect recognition, Bellack (1992) thinks that schizophrenics

shown a marked deterioration, especially in the ability to identify negative affects

shown by others. Leff & Abberton (1981) related these deficits in schizophrenic patients

with emotional flattening. It is known that different aspects of social perception such

as facial affect recognition, perception of dynamic social stimuli and self-perception are

related to social functioning in schizophrenia (Frith, 1995; Penn, Combs & Mohamed,

2001). Although literature shows the referred results, mediator processes among

neurochemical dysfunction and behavioural symptoms have not been studied in intervention

programmes. Roder, Brenner, Hodel & Kienzle (1996) indicate that among the mediator

processes, attention and perception processes are especially affected, as well as those

of recognition, integration and transformation of internal and external stimuli.

In fact, it is considered that the interventions focused in the social perception

skills should serve to improve generalization of treatment and its maintenance (Penn et

al., 2001).

Roder et al. (1996) have developed an integrated therapy for schizophrenic patients

(IPT) (Integriertes psychologisches Therapieprogramm fur schizophrene Patienten) with

the purpose of working as much on cognitive functioning as on social functioning in

schizophrenic patients. It is a group intervention programme with five subprogrammes:

Cognitive Differentiation, Social Perception, Verbal Communication, Social Skills Training

and Interpersonal Problem Solving. They are hierarchically ordered so the first interventions

are directed to basic cognitive skills, the next interventions transform the cognitive

skills into social and verbal behaviours, and the last ones train the patients in the

solution of more complex interpersonal problems. Nowadays IPT is considered a good

© Intern. Jour. Psych. Psychol. Ther.

AN APPLICATION OF THE IPT IN A SPANISH SAMPLE 301

procedure, with sufficient empirical support for schizophrenia treatment (Pérez &

Fernández, 2001; Vallina & Lemos, 2001)

In this investigation we have trained social perception skills in a schizophrenic

group of patients through the application of the second IPT programme. Some authors

(Vallina et al., 2001) consider it to be a basic programme because it contains the

essence of all the cognitive interventions which included IPT (reception of information,

its analysis and the emission of responses made after previous information has been

received and analyzed). These three cognitive processes are the basis for the

implementation of techniques and procedures used in the intervention package.

Research in which IPT is evaluated doesn’t specifically assess social perception.

Usually the considered measures in literature are: memory, verbal fluency, executive

functions, synonyms and antonyms, word recognition, concentration and short and long

term memory (Kraemer, 1991; Penadés, 2002; Roder, Studer & Brenner, 1987). Other

assessment instruments used in these studies are: Benton Test (Brenner, Hodel, Kube

& Roder, 1987a), and Frankfurt Test (FCQ) (Brenner, Hodel, Roder & Corrigan, 1992;

Vallina et al., 2001).

Because of this lack of attention to the evaluation of social perception, a Social

Perception Scale (EPS) has been developed considering the three phases of the Social

Perception Programme. This instrument is intended to evaluate changes produced by

the training in social perception, and also to know at which moment the patient is

prepared to go to the next programme. The effectiveness of the programme has also

been studied when applied to patients with more deterioration than those that usually

participate in this type of research. For example, in the study of Brenner et al. (1987a),

the average IQ of the 43 participants was 98, and the duration of the illness was of

nearly 6 years. Although in other studies, the average duration of the illness range

between 7 and 10 years (Brenner, Boker, Muller, Spichtig & Wurgler, 1987b; Hodel &

Brenner, 1994; Vallina et al., 2001).

METHOD

Participants

Patients from this report are users of the Centre of Mental Health of Aldaia

(Valencia), and attend the Association for Support to the Mental Health (AASAM)

association. The following selection criteria were applied: diagnosis of schizophrenia

according to CIE-10, without any organic damage nor abuse of alcohol or drugs, and

to be in an age range between 18 and 50 years. All the patients were receiving

pharmacological treatment either typical (haloperidol, fluphenazine) or atypical

antipsychotics (clozapine, risperidone). A brief interview with the 25 patients with

those requirements was made to evaluate their IQ using two tests: the vocabulary test

of the WAIS-III (verbal), and the Toni-2 test (nonverbal). Criteria for the inclusion in

the program were: a score of 4 in the vocabulary test or an IQ of 65 in the TONI-2 test.

After the application of this criteria the number of participants was reduced to 23. 13

of them were assigned to the therapy group and 10 to the control group. The sample

was matched by demographic and clinical data as shown in Table 1.

302

© Intern. Jour. Psych. Psychol. Ther.

S. GARCÍA, I. FUENTES, J. C. RUIZ, E. GALLACH, V. RODER.

Instruments

Following Wykes (2000) point of view we have considered three levels of analysis:

the neuropsychological, the clinical and the functional. According to this author, the

three levels are necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of any rehabilitation program.

In order to evaluate the changes the following scales were administered at the beginning

of the treatment and three months later, just when the Social Perception Programme

finished.

Social Perception Measures

Social Perception Scale (EPS) (García, 2003). The instrument is structured

according the three phases of the Social Perception Programme of the IPT: First, stimuli

identification; second, interpretation; and third, title assignment.

Four photographs and register sheets were used to assess patients in the three

aspects in which the programme focuses. Photographs were taken from the 40 slides

that integrate the program (numbers: 02, 05, 06 and 07). Two of them were chosen

because they had a high cognitive complexity, and the other two because they had a

high emotional content. After giving a photograph to the subject and inviting him to

observe it, the following questions were asked: What details/stimuli can you see in the

photograph? (First part); What is happening in the photograph? (Second part); What

title can summarise the more relevant aspects in the photograph? (Third part). Answers

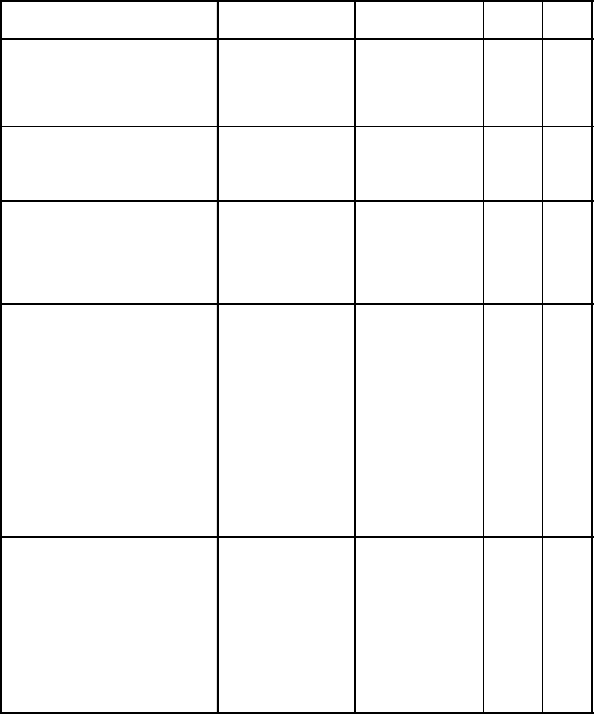

Table 1. Demographic and social characteristics of subjects

Characteristics Treatment group Control group

Number of subjects 11 9

Age (mean/sd) 40.45 (7.10) 36.88 (8.10)

IQ (mean/sd) 75.90 (14.07) 73.55 (10.63)

Sex: Male

Female

9

2

5

4

Education: Illiteracy

Primary school not completed

Primary school

Secondary school

1

4

4

2

0

5

2

2

Occupational situation: Pensioner 11 9

Housing situation: Alone

Sheltered home

With parents

With brothers/sisters

1

2

6

2

0

1

7

1

Ma rital status: Single

Divorced

11

0

8

1

Diagnostics: Hebefrenic

Undifferentiated

Paranoid

Residual

3

1

5

2

1

1

6

1

Duration illness (mean years) 21 14.77

© Intern. Jour. Psych. Psychol. Ther.

AN APPLICATION OF THE IPT IN A SPANISH SAMPLE 303

corresponding to each part were noted on to the register sheet. In the first part of the

register sheet there is a list containing the stimuli present in the image with which to

score patients later. In this part the patient has one and a half minutes to say which

stimuli were in the photographs. With answers of the patient in this first part three

scores were obtained: proportion of identified stimuli, number of errors, and number of

interpretations made. In the second part, subject answers were valued using a Likert

scale: 0 (no answer), 1 (no appropriate interpretation), 2 (partially appropriate

interpretation) and 3 (appropriate interpretation). In the third part patient answers were

again valued using a Likert scale: 0 (no answer), 1 (no appropriate title), 2 (partially

appropriate title) and 3 (appropriate title). These two scores were then transformed into

proportions, taking into account the maximum score in each part was 12.

In the assessment of the second and third part, it was relevant that the answers

of the subjects made reference to the situational context, actor/s, and the action or

interaction among them. So when answers didn’t allude to any of these aspects or only

to one of them, but add imagined aspects, the score of the answer was 1. If it made

reference to two of the indicated aspects, the score was 2. And finally, if it made

reference to three, the score was 3.

Attention

Test of Sustained and Selective Attention (TASS) (Batle and Tomás, 1999). It has

different geometric figures, and the task consists of ticking some of them with a cross.

Specifically the patient has to mark "the yellow circles and all the squares of any

colour". The time for the task, in the form that we have used (A) is 8 minutes. This test

evaluates sustained and selective attention.

Psychopathology

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Lukoff, Nuechterlein and Ventura, 1986).

The scale contains 24 items. Each one scores according to a Likert type scale (1 is

equivalent to no symptoms and 7 to extreme gravity). It also gives scores in 5 subscales

and a global score (see table 2). This instrument, as well as the next two, were not

administered by the investigators, but by an expert of the mental health personnel of

Aldaia.

Frankfurt Complaint Inventory (FBF-3) (Süllwold and Huber, 1986). We have

used the version of this self-report made by Jimeno, Jimeno & Vargas (1996), which

contains 98 items distributed in 10 scales (see table 2).

Social Functioning

Disability Assessment Schedule (DAS II) (WHO, 1985). The adaptation made by

Montero, Bonet, Puche & Gomez Beneyto (1988) was used. This test is conducted

through an interview between the expert and the patient or someone known the patient.

It is evaluated in a 9 points scale of gravity, that range from "non-dysfunctial" (0) to

304

© Intern. Jour. Psych. Psychol. Ther.

S. GARCÍA, I. FUENTES, J. C. RUIZ, E. GALLACH, V. RODER.

"completely dysfunctional most of the time" (8). The first part of the interview (General

Behaviour), the second part (Social Roll Execution) and the fifth part (Global Assessment)

were used. Four items of the second part were excluded, due to the characteristics of

the sample, as they were impossible to evaluate (see table 2).

Procedure

Two groups, one of control and one experimental, were used in a completely

randomized design. Both groups were evaluated in the different dependent variables

before and after the application of the treatment. The therapy group was divided into

two groups for the psychological intervention programme, so the number of participants

in each group was, at the beginning, 7 and 6 but, due to the absence of two of the

subjects, the final groups were formed by 6 and 5 respectively. The clinical intervention

in the therapy group was based on the application of the Social Perception Programme.

The duration of the treatment was 3 months. The frequency of the sessions was twice

a week for each therapy group, with a duration of 30 minutes in the first five sessions

(because only one slide was used) and 60 minutes for the rest (working with two slides

per session). The total number of sessions was 21.

In the first sessions, slides with low cognitive complexity and low emotional

content were used. Later on, slides with more cognitive complexity were added, and

from time to time, slides with more emotional content were included. The total number

of slides used was 36 (because 4 were employed in the EPS). Positioning of the chairs

in a semicircle was habitual in the application of the programme, with a big table in

the centre to write the titles. The distribution of the seats guaranteed the visual contact

between the participants themselves and with the therapists. Two professionals applied

the programme, a therapist and a Co-therapist, both of them assuming the recommended

functions of the IPT authors (Roder et al., 1996).

The application of the Social Perception Programme intends to improve the

perception and interpretation of social situations. This programme has three phases:

first, the participants must say all possible details presented in the image. This phase

is essential for the rest of the programme because the collected information will be used

by the participants to explain and justify their own interpretations; second, participants

give their opinion about the content of the image, and it must be justified with the

visual information gathered before. Later on, a debate begins looking for the most

appropriate interpretation of the social situation that appears in the slide. Finally, in the

third phase, each patient gives a title to the image making reference to the more

relevant aspects of it.

RESULTS

Non-parametrical statistical procedures were used throughout the analyses. Group

differences before and after the treatment between the experimental and control groups

were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Pre-test/post-test intervention differences

in both groups were analyzed using the Wilcoxon test. Effect sizes were also calculated

© Intern. Jour. Psych. Psychol. Ther.

AN APPLICATION OF THE IPT IN A SPANISH SAMPLE 305

in order to describe the relevance of changes after the treatment in the therapy group.

Group differences before treatment: Baseline differences between groups were

examined by the Mann-Whitney U-test. This analysis showed significant differences in

just three measures: EPS (quality of the title, z= 2.41, p= 0.016); Frankfurt (lost of

control, z= 2.00, p= 0.045); and DAS II (social contacts, z= 2.01, p= 0.044), indicating

that the two groups, were to a great extent, homogeneous before the intervention.

Group differences after treatment: Due to the absence of some data, the statistical

analysis of the FBF scores were calculated with 7 subjects corresponding to the control

group and 5 to the the experimental group. The analysis revealed that although there

were no clinical differences between the two groups, they differ in four of the five

scores of the social perception scale: proportion of identified stimuli (z= 2.43, p=

0.015); number of interpretations (z= 2.81, p= 0.005); proportion of adequate interpretations

(z= 2.02, p= 0.043); and quality of the title (z= 2.97, p= 0.003). There were no differences

Table 2. Pre-test/post-test treatment measures for the control group and

Wicolxon “z” values (NS= not significant).

VARIABLES PRE-TEST

MEAN (SD)

POST-TEST

MEAN (SD)

Z P

EPS

Proportion of identified stimuli

Number of interpretations

Number of errors

Proportion of adequate interpretations

Proportion of quality title

35.32 (10.50)

5.22 (2.11)

2.44 (1.42)

63.89 (12.50)

55.56 (10.21)

36.65 (9.96)

5.33 (1.66)

2.11 (1.45)

61.11 (8.33)

49.07 (15.28)

-0.42

-0.28

-0.72

-0.68

-1.15

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

TASS

Direct Score

Hits

Omission

Errors

10 2.22 (45.45)

10 9.78 (31.79)

13.89 (14.40)

1.67 (3.91)

107.09 (36.25)

114.78 (33.33)

10.00 (12.94)

.67 (1.12)

-1.01

-1.76

-2.20

-0.14

NS

NS

.028

NS

BPRS

Anxiety / Depression

Thought disorders

Anergia

Activation

Hostility

Total Score

7.44 (3.40)

12.33 (7.38)

8.89 (4.51)

7.00 (5.63)

8.56 (6.21)

44.22 (21.92)

8.33 (3.54)

8.78 (4.60)

5.00 (1.00)

4.11 (2.62)

5.00 (3.04)

31.22 (7.22)

-0.86

-1.52

-2.20

-1.78

-1.61

-2.10

NS

NS

.028

NS

NS

.035

FBF-3

Loss of control

Simple perception

Complex perception

Speech

Cognition and Thought

Memory

Motor behavior

Loss of automatic behavior

Depression

Stimuli overload

Factor 1. Cognition Disorder.

Factor 2. Perception-Motor skills

Factor 3. Depression

Factor 4. Stimuli Overload.

Total Score

4.14 (1.77)

2.00 (2.00)

3.57 (3.21)

5.71 (2.14)

4.57 (3.21)

5.00 (3.27)

2.86 ( .69)

5.00 (2.24)

3.29 (2.50)

4.14 (1.57)

9.14 (4.63)

7.57 (4.58)

13.57 (6.21)

9.00 (4.08)

40.00 (17.33)

4.00 (2.00)

3.29 (2.69)

4.29 (2.50)

6.71 (2.69)

5.00 (3.16)

5.43 (2.51)

4.43 (2.07)

5.86 (1.86)

4.43 (2.23)

4.43 (1.81)

11.00 (3.91)

10.71 (5.35)

15.57 (5.74)

9.00 (4.08)

48.29 (18.13)

-0.37

-0.77

-0.81

-0.86

-0.43

-0.54

-1.63

-0.85

-0.85

-0.70

-1.02

-1.27

-1.02

-0.35

-0.95

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

DAS II

Self -Care

Leisure time

Slowness

Communication

Participation in household

Social Contacts

Performance at work

Interest in getting a job

General Interest

Emergency or crisis behavior

Social Adjustment Total Score

2.22 (3.03)

4.56 (3.13)

2.56 (2.55)

3.56 (2.92)

3.22 (3.15)

2.44 (2.46)

3.63 (2.13)

4.11 (2.33)

4.44 (3.54)

4.11 (3.02)

3.11 (1.05)

2.56 (2.74)

2.33 (1.66)

1.56 (1.42)

3.56 (3.05)

1.67 (1.41)

2.11 (2.71)

3.89 (2.80)

4.89 (2.52)

4.78 (2.91)

4.22 (3.11)

3.00 ( .87)

-0.55

-1.87

-1.06

-0.09

-1.36

-0.53

-0.68

-0.17

-0.34

-0.07

-0.38

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

306

© Intern. Jour. Psych. Psychol. Ther.

S. GARCÍA, I. FUENTES, J. C. RUIZ, E. GALLACH, V. RODER.

in the EPS score ‘number of errors’ probably due to a floor effect. These results point

out an improvement in the perception and interpretation of social situations in the

therapy group.

Pre-test/post-test intervention changes: Pre-tests/post-test changes were analyzed

in both groups in every measure. As shown in Tables 2 and 3 there were no significant

differences in most of the cognitive, social functioning and psychopathology measures

in both groups. However some specific changes were observed. In the control group

there were significant changes in one TASS score (omissions) and in two BPRS scores

(anergia and total score). In the therapy group there were significant changes in one

Table 3. Pre-test/post-test treatment measures for the therapy group and

Wilcoxon´s “z” values (NS= not significant).

VARIABLES PRE-TEST

MEAN (SD)

POST-TEST

MEAN (SD)

Z P

EPS

Proportion of identified stimuli

Number of interpretations

Number of errors

Proportion adequate interpretations

Proportion quality title

34.87 (10.43)

6.00 (2.57)

1.82 (1.25)

56.82 (9.73)

43.18 (11.07)

48.98 (9.90)

2.45 (1.97)

1.36 ( .81)

78.79 (18.40)

80.30 (19.82)

-2.86

-2.50

-0.97

-2.81

-2.81

.004

.012

NS

.005

.005

TASS

Direct Score

Hits

Omission

Errors

104.37 (50.90)

115.36 (51.50)

5.45 (6.58)

3.60 (9.93)

106.16 (40.00)

110.73 (33.66)

7.09 (10.63)

.45 (1.21)

-0.62

-0.66

-0.46

-1.07

NS

NS

NS

NS

BPRS

Anxiety / Depression

Thought disorders

Anergia

Activation

Hostility

Total Score

7.27 (3.64)

9.82 (5.36)

7.45 (2.62)

5.09 (2.66)

4.64 (2.50)

34.36 (13.06)

7.18 (2.75)

6.73 (3.13)

5.00 (2.41)

4.36 (2.01)

4.18 (2.99)

27.36 (8.29)

-0.18

-1.47

-1.84

-0.85

-0.53

-1.56

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

FBF-3

Loss of control

Simple perception

Complex perception

Speech

Cognition and Thought

Memory

Motor behavior

Loss of automatic behavior

Depression

Stimuli overload

Factor 1. Cognition Disorder.

Factor 2. Perception-Motor skills

Factor 3. Depression

Factor 4. Stimuli Overload.

Total Score

1.80 (1.30)

4.00 (3.08)

3.40 (2.07)

5.60 (2.88)

4.60 (2.70)

5.00 (2.92)

4.60 (2.70)

4.00 (2.74)

4.00 (2.12)

3.80 (1.79)

8.80 (3.27)

11.00 (7.48)

11.00 (5.05)

8.80 (3.42)

40.80 (17.04)

4.40 (2.30)

4.00 (2.74)

5.40 (2.41)

6.60 (2.30)

6.80 (1.30)

5.60 (2.19)

5.20 (3.70)

6.20 (3.03)

5.00 (1.41)

6.00 (1.41)

13.60 (4.39)

15.00 (8.15)

16.00 (2.65)

11.40 (2.88)

56.00 (15.65)

-1.46

-0.00

-0.81

-0.68

-1.84

-0.54

-0.37

-0.41

-0.96

-1.51

-1.49

-0.73

-1.22

-0.96

-0.94

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

DAS II

Self -Care

Leisure time

Slowness

Communication

Partic ipation in household

Social Contacts

Performance at work

Interest in getting a job

General Interest

Emergency or crisis behavior

Social Adjustment Total Score

1.82 (2.79)

4.18 (2.60)

2.27 (2.53)

4.27 (3.00)

2.50 (2.88)

0.60 (1.35)

2.20 (2.30)

3.78 (2.59)

4.73 (2.90)

5.27 (3.10)

3.00 ( .89)

1.64 (1.57)

1.91 (1.22)

1.64 (2.06)

2.09 (2.74)

2.09 (1.92)

.64 (1.21)

2.27 (2.28)

3.36 (3.11)

4.64 (2.87)

4.45 (2.46)

2.64 (1.12)

-0.21

-2.30

-0.67

-1.69

-0.85

-0.00

-0.26

-0.17

-0.12

-1.18

-1.27

NS

.021

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS

© Intern. Jour. Psych. Psychol. Ther.

AN APPLICATION OF THE IPT IN A SPANISH SAMPLE 307

DAS II score (leisure time). But the results were quite different in social perception

measures. There wasn’t any pre-test/post-test change in the control group, but there

were significant and positive differences in four EPS scores (proportion of identified

stimuli; number of interpretations; proportion of adequate interpretations; and quality

of the title). Comparing the changes which occurred in the group it can be observed that

experimental patients: increase the proportion of identified stimuli, decrease the number

of interpretations, increase the proportion of adequate interpretations, and also increase

the quality of the title. There were probably no differences in the number of errors due

to a floor effect. Taken together, the obtained results reveal that the IPT program was

effective in producing a significant positive effect on the perception and correct

interpretation of social situations in these patients, measured through the EPS.

Effect sizes defined by the difference of the baseline with the measurement point

after treatment divided by the standard deviation of the whole sample at baseline (Roder

et al., 2002) were also calculated for all measurements in the therapy group (see Table

4). The overall strongest effects were obtained on EPS measurements, all the effects

indicated improvement and, except in the ‘number of errors’, they reached the level of

large effect size. In the rest of the measurements the group has also shown some

important improvements as in: BPRS scores (anergia and total score) and DAS II scores

(free time and communication).

Additionally, the correlation (Pearson coefficient) between the scores of the two

Table 4. Effect size measurements for the therapy group

EPS

ES

Proportion of identified stimuli 1.39

Number of interpretations -1. 51

Number of errors -0. 34

Proportion of adequate interpretations 1.94

Proportion of quality title 3.05

TASS

Direct Score 0.04

Hits -0. 11

Omission 0.14

Errors -0. 46

BPRS

Anxiety / Depression

-0. 03

Though t disorders

-0. 49

Anergia

-0. 69

Activation

-0. 17

Hostility

-0. 09

Total Score

-0. 39

DAS II

Self-Care

-0. 06

Leisure time

-0. 82

Slowness

-0. 26

Communication

-0. 75

Participation in household

-0. 14

Social Contacts 0.02

Performance at work

0.03

Interest in getting a job

-0. 17

General Interest -0. 03

Emergency or crisis behavior

-0. 27

Social Adjustment Total Score

-0. 38

308

© Intern. Jour. Psych. Psychol. Ther.

S. GARCÍA, I. FUENTES, J. C. RUIZ, E. GALLACH, V. RODER.

therapists who marked the EPS was calculated to evaluate the fiability of the scores.

Correlation was high in every EPS score with ranges between 0.96 and 1.00 in both,

pre-test and post-test measurements.

DISCUSSION

Results show that the Social Perception of the patients who participated in the

programme has improved, and this fact reveals that this programme contributes to the

acquisition of social perception cognitive skills. Subjects that have received training in

Social Perception learn to collect more information (identifying more stimuli) of an

image, to make better interpretations of it and to summarise, with a title, the most

important information of it. In addition, we found that the EPS is very sensitive to the

produced changes, and that inter-observer agreement is very high. Therefore, we have

developed an instrument which can help the therapist to decide when a patient is

prepared for the next IPT programme.

Results have not shown significant differences in attention between the therapy

and control group. So, it can be assumed that the Social Perception Programme does

not improve attention capacities as we have evaluated them. In fact, another IPT

programme, the Cognitive Differentiation one, is the one orientated to improve attentional

processes, especially selective, focused and sustained attention. The intervention has

not reduced the symptoms in the schizophrenic patients. Although significant improvements

in psychopathological parameters and social role-functioning were not expected because

it was a short intervention and patients were of long illness duration, analysis of effect

sizes have shown positive changes in some scores: anergia, thought disorders, and total

score (BPRS); leisure time and communication (DAS-II).

These results are in line with the Capability of Penetration Model (Brenner,

1989). This model is based on three assumptions: (1) schizophrenics show deficits in

different functional levels of behaviour organization, (2) deficits in one level can affect

functions in other levels, and (3) different levels follow a hierarchic relation among

them. The model also affirms that an improvement in cognitive functioning has a deep

effect on all behaviour organization levels.

Our results are similar to the ones obtained by Kraemer et al. (1991) who, after

applying the Cognitive Differentiation, Social Perception and Interpersonal Problem

Solving programs, found differences in cognitive functioning but non-significant

improvements in psychopathology. So it can be confirmed that those investigations that

find differences in psychopathology and social functioning are those that use the com-

plete IPT like Brenner’s et al. (1987a), or at least four of its five programs like Vallina´s

et al. (2001).

Finally, emphasis must be made that, although IPT authors recommend to work

with patients with a minimum IQ of 85, in our investigation patients with less IQ also

benefited from the intervention. In summary, it can be stated that if only the Social

Perception Programme of the IPT is applied, chronic schizophrenics improve their

capacity to perceive and to interpret social reality.

© Intern. Jour. Psych. Psychol. Ther.

AN APPLICATION OF THE IPT IN A SPANISH SAMPLE 309

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank María Huertas, the AASAM and Amparo Bonora for their

help.

REFERENCES

Batlle, S. & Tomás, J. (1999). Evaluación de la Atención en la Infancia y la Adolescencia: Diseño de

un Test de Atención Selectiva y Sostenida. Estudio piloto. Revista Española de Psiquiatría

Infanto-Juvenil, 3, 142-148.

Bedell, J.R. & Lennox, S.S. (1994). The standardised assessment of cognitive and behavioral components

of social skills. In J.R. Bedell (ed.). Psychological assessment and treatment of persons with

severe mental disorders. London: Taylor & Francis.

Bellack, A.S. (1992). Cognitive rehabilitation for schizophrenia: Is it possible? Is it necessary?.

Schizophrenia Bulletin, 18, 43-50.

Bellack, A.S., Blanchard, J.J. & Mueser, K. (1996). Cue availability and affect perception in

schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 22, 535-544.

Brenner, H.D., Hodel, B., Kube, G. & Roder, V. (1987a). Kognitive Therapie bei Schizophrenen:

Problemanalyse und empirische Ergebnisse. Nervenarzt, 58, 72-83.

Brenner, H.D., Boker, W., Muller, J., Spichtig, L. & Wurgler, S. (1987b). On autoprotective efforts of

schizophrenics, neurotics and controls. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 75, 405-414.

Brenner, H.D. (1989). The treatment of basic psychological dysfunctions from a systemic point of

view. British Journal of Psychiatry, 155, 74-83.

Brenner, H.D., Hodel, B., Roder, V. & Corrigan, P.W. (1992). Treatment of cognitive Dysfunctions

and Behavioral Deficits in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 18, 21-26.

Corrigan, P.W. & Green, M.F. (1993). Schizophrenics Patients Sensitivity to Social Cues: The Role of

Abstraction. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 589-594.

Frith, C.D. (1995). La esquizofrenia. Un enfoque neuropsicológico cognitivo. Barcelona: Ariel.

García, S. (2003). Rehabilitación de enfermos mentales crónicos: Entrenamiento en Percepción So-

cial. Trabajo de Investigación. Departamento de Personalidad, Evaluación y Tratamientos Psi-

cológicos. Universidad de Valencia.

Halford, W.K. & Hayes, R. (1991). Psychological rehabilitation of chronic schizophrenic patients:

recent finding on social skills training and family psychoeducation. Clinical Psychology Review,

11, 23-44.

Hodel, B. & Brenner, H.D. (1994). Cognitive therapy with schizophrenic patients: conceptual basis,

present state, future directions. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 90, suppl 384, 108-115.

Ibáñez, T. (1979). Factores sociales de la percepción. Hacia una psicosociología del significado. Cua-

dernos de Psicología, 1, 71-81.

Jimeno, N., Jimeno, A. & Vargas, M.L. (1996). El Síndrome psicótico y el Inventario de Frankfurt.

Conceptos y resultados. Barcelona: Springer.

Kraemer, S. (1991). Cognitive training and social skills training in relation to basic disturbances in

chronic schizophrenic patients. In C.N. Stefanis (ed.). Proceedings of the World Congress of

310

© Intern. Jour. Psych. Psychol. Ther.

S. GARCÍA, I. FUENTES, J. C. RUIZ, E. GALLACH, V. RODER.

Psychiatry. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Leff, J. & Abberton, B. (1981). Voice pitch measurements in schizophrenia and depression. Psychological

Medicine, 11, 849-852.

Lukoff, D., Nuechterlein, K.H. & Ventura, J. (1986). Manual for Expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating

Scale (BPRS). Schizophrenia Bulletin, 12, 594-602.

Montero, I., Bonet, A., Puche, E. & Gómez Beneyto, M. (1988). Adaptación española del DAS-II

(Disability Assesment Shedule). Psiquis, 175, 17-22.

Morrison, R.L., Bellack, A.S. & Mueser, K.T. (1988). Deficits in facial-affect recognition and

schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 14, 67-83.

Organización Mundial de la Salud (1992). CIE-10. Trastornos Mentales del Comportamiento. Ma-

drid: Meditor.

Penadés, R. (2002). La Rehabilitación neuropsicológica del paciente esquizofrénico. Tesis Doctoral.

Departamento de Psiquiatría y Psicobiología Clínica. Universidad de Barcelona.

Penn, D.L., Comb D. & Mohamed, S. (2001). Social Perception in Schizophrenia. In P.W. Corrigan &

D.L. Penn (Eds.), Social Cognition and Schizophrenia. Washington: American Psychological

Association.

Pérez, M. & Fernández, J.R. (2001). El grano y la criba de los tratamientos psicológicos. Psicothema,

13, 523-529.

Roder, V., Studer, K. & Brenner, H.D. (1987). Erfahrunger mit einem intergrierten psychologischen

therapieprogramm zum training kommunikativer und kognitiver fahigkeiten in der rehabilitation

schwer chronisch schizophrener patienten. Schweizer Archiv Fur Neurologie und Psychiatrie,

138, 31-44.

Roder, V., Brenner, H.D, Muller, D, Lachler, M., Muller, R. & Zorn, P. (2002). Social skills training for

schizophrenia: Research update and empirical results. In H. Kashima., I.R.H. Falloon., M.

Mizuno, & M. Asai (Eds.), Comprehensive Treatment of Schizophrenia. Tokyo: Springer.

Roder, V., Brenner, H.D., Hodel, B. & Kienzle, N. (1996). Terapia Integrada de la Esquizofrenia.

Barcelona: Ariel.

Süllwold, L. & Huber, G. (1986). Schizophrene basisstörungen. Berlin: Springer.

Toomey, R., Wallace, C.J., Corrigan, P.W., Schulderg, D. & Green, M.F. (1997). Social processing

correlates of nonverbal perception in schizophrenia. Psychiatry, 60, 292-300.

Vallina, O., Lemos, S., Roder, V., García, A., Otero, A., Alonso, M. & Gutiérrez, A.M. (2001). Controlled

study of an integrated psychological intervention in schizophrenia. The European Journal of

Psychiatry, 15, 167-179.

Vallina, O. & Lemos, S (2001). Tratamientos psicológicos eficaces para la esquizofrenia. Psicothema,

13, 345-364.

World Health Organization (1985). A procedure and schedule for assessment of disability in patients

with severe psychiatric disorders. Disability Assessment Schedule-DAS-II. Geneva: WHO.

Wykes, T. (2000). Cognitive rehabilitation and remediation in schizophrenia. In T. Sharma & P. Arvey

(eds). Cognition in Schizophrenia. New York: Oxford University Press.

Received September 10, 2003

Final acceptance November 13, 2003