HAL Id: halshs-03370962

https://shs.hal.science/halshs-03370962

Submitted on 8 Oct 2021

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-

entic research documents, whether they are pub-

lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diusion de documents

scientiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Unequal housing aordability across European cities.

The ESPON Housing Database, Insights on

Aordability in Selected Cities in Europe

Renaud Le Goix, Ronan Ysebaert, Timothée Giraud, Marc Lieury, Guilhem

Boulay, Mathieu Coulon, Sébastien Rey-Coyrehourcq, Rémi Lemoy, José J

Ramasco, Mattia Mazzoli, et al.

To cite this version:

Renaud Le Goix, Ronan Ysebaert, Timothée Giraud, Marc Lieury, Guilhem Boulay, et al.. Unequal

housing aordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Database, Insights on Aordability

in Selected Cities in Europe. Cybergeo : Revue européenne de géographie / European journal of

geography, 2021, 974, �10.4000/cybergeo.36478�. �halshs-03370962�

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography

Datapapers|2021

Unequal housing affordability across European

cities. The ESPON Housing Database, Insights on

Affordability in Selected Cities in Europe

L’inégale abordabilité du logement dans les villes européennes. La base de

données ESPON sur le logement, aperçu des prix dans une sélection de villes

Européennes

El desigual acceso a la vivienda en las ciudades europeas. Aproximación a su

estudio en función del precio a partir de la base de datos ESPON

RenaudLeGoix,RonanYsebaert,TimothéeGiraud,MarcLieury,Guilhem

Boulay,MathieuCoulon,SébastienRey-Coyrehourcq,RémiLemoy,JoséJ.

Ramasco,MattiaMazzoli,PereColet,ThierryTheurillat,Alain

Segessemann,SzymonMarcińczakandBartoszBartosiewicz

Electronicversion

URL: https://journals.openedition.org/cybergeo/36478

DOI: 10.4000/cybergeo.36478

ISSN: 1278-3366

Publisher

UMR 8504 Géographie-cités

Brought to you by Université de Paris

Electronicreference

Renaud Le Goix, Ronan Ysebaert, Timothée Giraud, Marc Lieury, Guilhem Boulay, Mathieu Coulon,

Sébastien Rey-Coyrehourcq, Rémi Lemoy, José J. Ramasco, Mattia Mazzoli, Pere Colet, Thierry

Theurillat, Alain Segessemann, Szymon Marcińczak and Bartosz Bartosiewicz, “Unequal housing

affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Database, Insights on Affordability in

Selected Cities in Europe”, Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography [Online], Data Papers, document

974, Online since 16 April 2021, connection on 08 October 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/

cybergeo/36478 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/cybergeo.36478

This text was automatically generated on 8 October 2021.

La revue Cybergeo est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution

4.0 International.

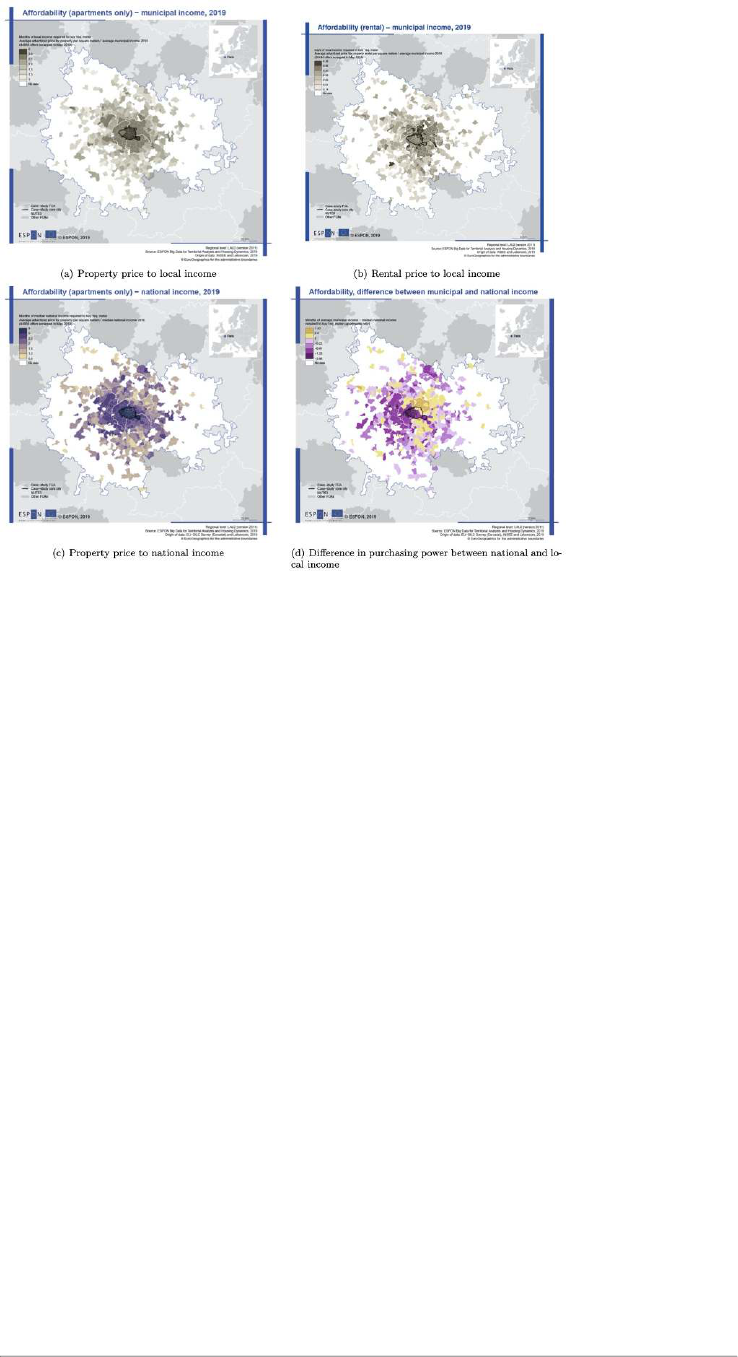

Unequal housing affordability

across European cities. The ESPON

Housing Database, Insights on

Affordability in Selected Cities in

Europe

L’inégale abordabilité du logement dans les villes européennes. La base de

données ESPON sur le logement, aperçu des prix dans une sélection de villes

Européennes

El desigual acceso a la vivienda en las ciudades europeas. Aproximación a su

estudio en función del precio a partir de la base de datos ESPON

Renaud Le Goix, Ronan Ysebaert, Timothée Giraud, Marc Lieury, Guilhem

Boulay, Mathieu Coulon, Sébastien Rey-Coyrehourcq, Rémi Lemoy, José J.

Ramasco, Mattia Mazzoli, Pere Colet, Thierry Theurillat, Alain

Segessemann, Szymon Marcińczak and Bartosz Bartosiewicz

AUTHOR'S NOTE

First and second authors designed and led the study, wrote the paper, and contributed

equally. Other authors have been in charge of national contributions to the database

and analysis, edition of the text, and contributed equally.

1 Introduction

1 Providing the means of a better knowledge of housing affordability is becoming

increasingly important, for public policies and scholarly research. This data-paper

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

1

presents and describes a consolidated, harmonized, internationally comparable

database to quantify the impacts of the housing affordability crisis. This database is

structured to promote some means to understand key issues in urban areas: social

filtering processes, gentrification, accumulation, and socio-economic inequalities more

generally. We do so by discussing a methodological framework to integrate

neighborhood and local spatial data, structured with harmonized indicators, to

examine and compare the unequal spatial patterns of housing affordability across

Europe.

2 The dataset derives from the ESPON Big Data for Territorial Analysis of Housing Dynamics

2018-19 applied research program. ESPON EGTC is a regional planning agency for the

European Commission. In European larger cities decent and affordable housing is

increasingly hard to get access to: the goal of the study is to inform the increased and

unequal affordability gap at the local geographical level, with tools for comparison

between cities, and within cities.

3 The aim of the original ESPON report published in 2019 was to inform European public

policies in territorial cohesion. The report has been drafted with a description and

discussion of the results, in an analysis of the unequal spatial patterns of

unaffordability in Europe. Information regarding the reproducibility of the work and

data collection has also been added to the report, as appendix. The aim of this data

paper is to complement the report with a full description of the database constructed,

its metadata, the possible usages for further research, and procedures for

reproducibility and future additions to the database. We do so and present the

structure of the database, how it has been constructed in a reproducible manner ; we

document the validation process, the strengths and limitations of the data provided,

and document the reproducibility of the workflow. The database stored on the Nakala

open access respository comes with a fully reproducible example documented as a

RMarkdown document

1

.

4 The database has been structured so as to answer several issues altogether, that are the

theoretical backbones of the research. One dimension of the problem is unequal access

to housing opportunity with regard to income and wealth of households. Another

dimension is that this gap has widened during the last decades. Since the 1990s,

housing prices have on average increased faster than the income of residents and

buyers in major post-industrial city-regions, but this trend is not ubiquitous and there

are some exceptions. Second, since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) more

specifically, the affordability crisis seems to have followed unprecedented pathways of

accumulation and vulnerability for households in OECD countries: general price

inflation has maintained, but also with greater instability and volatility of local trends.

A third issue between European cities is the variegated pathways housing regimes have

followed since the GFC. The notion of housing regime can be defined as the systemic

relationship between diverse housing systems, tenure and provision arrangements, and

wider welfare regimes (Arbaci 2007 ; Tammaru et al. 2019). A decline of ownership has

been observed in some countries (Byrne 2020) with an unprecedented growth of the

private rental sector. In other countries, ownership has stabilized and other forms of

access to housing have emerged, with new regulations of the rental sector as an

alternative to social rental and owner-occupied housing, like in the Netherlands and

France for instance (Wijburg 2019; Hochstenbach and Ronald 2020).

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

2

5 Our research also copes with a data gap, i.e., a lack of harmonized spatial data to map

affordability in Europe. Institutional, private, national or local data do exist. But these

are not harmonized and inter-operable, not fit for comparison (Julliard and Gusarova

2019), and Eurostat does not provide local indicators on affordability. To cope with this

data gap, the paper brings new insights on how (1) institutional data, such as

transaction data, can be bridged with (2) unconventional data (“big data” harvested on

line) to provide a cost-effective and harmonized data collection effort that can

contribute to the analysis of affordability. We aggregated the data in various

geographical levels of analysis (1km square-grid, municipalities, FUA), following a

methodological framework to use local spatial data and to allow the comparison within

cities (between neighborhoods) and between cities, and designed to allow reproducing

in further studies. The methodology has been applied to 10 case-studies Functional

Urban Areas (FUAs) covering 4 countries of the ESPON Area, among which one cross-

border region: Geneva (Switzerland), Annecy-Annemasse, Avignon and Paris (France),

Madrid, Barcelona and Palma de Majorca (Spain) and Warsaw, Łódź and Krakow

(Poland). This database does not cover the entire set of FUAs, but has been designed as

a proof of concept, to envision a wider study that could bring together experts from

different countries in Europe, to build a more thorough analysis. Open code and

transferable methods are documented and disseminated with the ESPON study, to allow

further implementation.

6 Section 2 provides a literature review, and discusses the conceptual contribution of the

database in the wider context of a policy-oriented research on housing at a European

level. Section 3 presents the methods used for the data collection: data sources, spatial

coverage and case-studies, aggregation and harmonization procedures. It details the

conceptual and theoretical models applied to conduct the data collection, and the

methodological framework applied. We particularly insist on the effort to bridge the

gap by harmonizing conventional and institutional data sources, with unconventional

sources from the web ("big data"), to map affordability, along with the quality control

and data validation procedures. Section 4 is dedicated to presenting a possible use of

the dataset, by mapping and comparing local housing data and giving insights on the

main findings from the data. The final section is dedicated to metadata.

2 Context, literature review and contribution of the

database in housing research

7 This section discusses the policy context in which the production of the database took

place, and frames the issue of affordability and inflation, within the wider literature on

housing regimes and inequality. We argue that the lack of harmonized local spatial data

to map affordability in Europe is a major issue to better analyze and compare the

situation at local geographical levels. The aim of the ESPON database is to present data

and reproducible methods that contribute to filling this data gap.

2.1 Policy context : coping with inflation in Europe

8 Housing prices have increased faster than the income of renters and buyers in major

post-industrial city-regions, and real estate has become an important driver of socio-

economic inequalities: “in 2014, approximately 7% of the EU-28 population faced the

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

3

situation where housing costs accounted for more than half of their disposable income”

(Eurostat, 2016). This forms the basis of our study. The policy-oriented broader

reflection is to analyze the spatial dynamics of unequal local affordability, as framed by

the Action Plan of the Partnership on Housing of the UE Urban Agenda pushes for improved

knowledge regarding affordability of housing. We address the housing elements of

European policies through one major problem: affordability, a concept defined as a gap

between housing prices and households’ income (Tighe and Mueller 2012; Friggit 2017).

9 Housing is a major policy issue regarding urban well-being, cohesion and sustainability

in Europe. The study is framed by the Territorial Agenda of the European Union for 2020 and

deals with the impacts of housing on territorial cohesion, and how to tackle with risks

of exclusion. The Pact of Amsterdam (2016) recognizes housing as a key priority of the

Urban Agenda for the European Union, because it affects social cohesion and stability

in Europe, the Action Plan of the Partnership on Housing of the EU pushes for improved

knowledge regarding affordable housing.

10 This affordability crisis impacts the well-being of residents in European cities, and has

been well analyzed at macro-economic levels. As soon as the early 1990s, housing

finance (access to credit, mortgage and fiscal incentives for investors) has increased

dramatically in the Global North, yielding a continuous inflow of buyers on markets,

and a volatile inflation of price: residential mortgage outstanding debt reached as early

as 2006 an all-time high level: 35% (France), 50% (Sweden, Spain, Germany), 80% (US)

and 100% (Netherlands, Denmark) of the GDP, according to Schwartz and Seabrooke

(2009). A 2012 IMF report analyzed the change in household debt-to-income ratio

between 2002 and 2010: +100% in Ireland and the Netherlands, +45% in Spain, +50% in

Norway and in the UK, for instance

2

. Also, since the early 2000s, the gap between

households’ income and real estate prices has widened. For owner-occupied

households, in Britain, Ireland, the average price to income ratio of 3:1 in 1996 reached

values between 4:1 and 5:1 in 2007 (Schwartz and Seabrooke 2009). A study in 17

countries (14 in Europe, and the USA, Canada, Japan) showed that the homeownership

rates ranges between 50 to 83% in 2010. In many countries, homeownership

skyrocketed until the 1990s then stabilized. There is evidence that housing markets

have since switched to another more debt-driven inflation dynamic: data shows a

growth of mortgage debt without growth of ownership “in [a] majority of countries,

recent decades, particularly in the 2000s, were marked by a growth of mortgages per

GDP not paralleled by a growth of homeownership, which either grew much less than

before or even declined” (Kohl 2018, p. 185). In parallel, entire segments of the markets

have shifted to private rental, with a massive transfer of housing debt dedicated to

investments in private rental, a sector that has been framed by national policy regimes

(Wijburg 2019; Byrne 2020; Hochstenbach and Ronald 2020).

11 This results in an unprecedented inflation: in 1985-2010 price-to-income ratio has

increased from + 13% up to +28% in France, 44% in the UK, except in Germany and Japan

(Aalbers 2016). In France, affordability of homeownership, i.e. real estate purchase

power, calculated by dividing housing prices by level of wealth (income generally) has

dropped at its lowest historical level (Friggit 2017), because of a +70% increase of the

actual cost of real estate since 2000, while households benefited from lower interest

rates and longer credit range to offset this price inflation and maintain purchase

power. This is not, however, the case in every European country, as demonstrated in a

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

4

study by Beresewicz (2015), where data show a decreasing trend on the stock market in

Poland after 2008.

12 This affordability problem spreads across markets, with unequal effects (Kemeny 2001;

André and Chalaux 2018). The OECD Affordable Housing Database (AHD) characterizes the

various conditions existing on European markets. Data show that in many European

countries, price paid (through the average mortgage or rent burden) tops up the 25% of

disposable income critical threshold, in Norway, Finland, Czech Republic, Sweden, the

Netherlands, Greece, the UK, Denmark and Spain as for rents. For owner-occupied

households, this is measured by means of the cost of mortgage, and it reaches the

highest levels of disposable income in France, in Luxembourg, Ireland and Croatia.

Among lower-income owners, covering all individuals with a net income below 50% of

median income of total population, the situation shows critical threshold of debt (50%)

in 14 countries of the OECD study (Oecd 2018). For renters, the worst situations are

found in 9 countries among which Croatia, Greece, Spain, the UK and Portugal.

2.2 Literature review: affordability, housing regimes and inequalities

13 Given the effects of price inflation on price-to-income gap in European cities, it is

crucial to contextualize the issue within the different market regimes between

European cities, as a large part of the literature considers a global shift in market

regimes has occurred (Fernandez and Aalbers 2016). Affordability of housing has

become, in this context more and more socially and politically embedded in welfare.

14 This situation in European countries is linked with financial and macroeconomic

parameters like monetary policies, credit affordability and fiscal policies targeting

investment (national policies): 25 States in the OECD promote homeownership by

means of subsidies and fiscal incentives to first-time property owners and/or fiscal

incentives to offset the cost for individual buyers (André and Chalaux 2018). This shows

how advanced economies have shifted toward an asset-based welfare model, yielding a

regime linking an ideology of ownership, credit affordability and house price often

subsidized by the State and local governments (Ronald 2008; Rolnik 2013). Topalov

(1987) has well established how homeownership regimes shifted from a rentier-system

to a credit-based massive homeownership system. Such a shift has been regulated by

converging public policies (to increase household solvency and provide incentives to

homeownership), the banking industry, market players’ strategies (among which

developers have been preeminent), and preservation of assets strategies by households.

Some scholars describe a path dependency-shift in almost every nation-state

influenced by global World Bank policies (Rolnik 2013; Theurillat, Rérat, and Crevoisier

2015). Other studies suggest that housing regimes have also recently shifted towards a

retargeting of investment, from owner-occupied housing to private lenders: recent

studies showed that private sector rental has been preeminent in the restructuring of

credit markets since the GCF (Byrne 2020).

15 Trajectories are therefore highly dependent upon national frameworks, and the state

enables households to act as investors, engaging through markets with prospects of

future gains, while exposed to greater risks (volatility of price, loss of property values,

risks of bankruptcy and foreclosures, etc.), raising questions of individual and systemic

risks, and therefore vulnerabilities of households (Schwartz 2012).

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

5

16 This has also been a gradual shift in welfare, across national models (Fernandez and

Aalbers 2016). Housing asset-based welfare is described as a rising ideology of

ownership across modern-industrialized societies and a path dependency in housing

policy reforms (Malpass 2011), characterized market mechanisms driven by policy-

measures, socio-ideological frameworks (Ronald 2008) and finance-led accumulation

regimes (Boyer 2009). This holds for both owners and for private lenders, who are also

often households developing investment strategies to recycle accumulated wealth.

More specifically, theories link the high proportion of capital investment that housing

represents for households and the ways welfare states are organized and reformed

(Kemeny 2001), the pursuit of owner-occupancy being viewed as a superior form of

tenure, while privatizing social housing (Van Gent 2010).

17 The situation in Europe is very diverse in this respect. André and Chalaux (2018) used

the OECD database to identify four groups among a set of OECD countries, showing how

the dimensions of the affordability question are highly multifaceted, according to

various market regimes:

A group named "Northern", as it covers mainly Northern Europe, including

Germany, features extended private rental and generally high household debt. A

"Western" group, which includes France and the United Kingdom, has higher

home-ownership rates and more social housing. "Southern‐Central" and "Eastern"

groups gather European countries, where outright home-ownership is prevalent,

but housing conditions are poorer. (André and Chalaux 2018, p. 1)

18 One policy implication is that no single recommendation can be issued at a European

level regarding the affordability crisis, with regards to the diversity of market

conditions in Europe. Generally speaking:

For prospective homeowners: increased affordability gap leads to a socially-selective access

to housing markets, yielding more spatial exclusion and increased social tensions. Real

estate has become an important driver of socioeconomic inequalities, especially between

owners and renters, with different trajectories of wealth and accumulation.

The cost of ownership impacts rents, and also the availability of housing to let, especially

because of increased private rental that are substitutes to the withdrawal of the State from

public rental. The global financial and economic crisis also led to decreasing construction

activities across Europe, in particular with respect to social housing, as many governments

restrained their level of public spending.

For owners, real estate has become a major component of household wealth. But local

markets are also volatile. Housing prices are therefore unstable and contingent upon the

market’s continuous restratification within and across neighborhoods. Real estate

influences the local conditions through which household wealth is accumulated or lost (Le

Goix et al. 2021).

2.3 Filling a data gap

19 In such a context, the goal of the database is to detail the relationships between

income, price and local market conditions in European FUAs. However, one major issue

is the lack of harmonized spatial data to map and analyze affordability in Europe. There

are plenty of institutional (tax, census), private (real-estate agents and websites) and

national or local data (parcels, local tax rolls). These are not harmonized and easy to

inter-operate.

•

•

•

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

6

20 ESPON interest in the database has been policy oriented. However, data by OECD and

Eurostat are disseminated respectively at the national and at the city levels, but the

datasets are far from complete in terms of thematic and geographical objects available

to accurately analyze housing dynamics. The Urban Audit survey (Eurostat) publishes

some perception data on the conditions of housing, and annual statistic aggregates on

price, type of structure and households’ income, with an average degree of

completeness of 51%, along with missing data in several countries in Europe, including

France. The OECD database characterizes affordability as national aggregates, and

allows for comparisons to be made between countries (André and Chalaux 2018). To

compare housing situations between European cities, Eurostat provides some

indicators mainly derived from national censuses under the topic “living conditions”. It

provides basic distinctions between houses and apartments, housing type (owner-

occupied dwellings, households in social housing), as well as incomplete data on the

average price for buyers and renters and average income. Eurostat also provides an

overview of the distribution of housing conditions across the European urban

hierarchy.

21 Two shortcomings should be highlighted: (1) a lack of information regarding the

definition and harmonization between databases; (2) the market segments and spatial

coverages for which the aggregated information is relevant. These are common

problems when harmonizing national census definitions and highlight the

heterogeneity of national censuses led in each country in Europe. In short: some

datasets are available, but on many respects, there is a need for ways to bridge and

produce analysis at local level (Julliard and Gusarova 2019).

3 Methods

22 This section describes the steps required to select data sources, define case studies, and

data collection, harvesting and the methodology required to combine conventional and

unconventional data sources. We describe harmonization and aggregation procedures,

that are not only technical, but also conceptual. We finally discuss quality control and

data validation procedures, and finally missing data handling, by means of

interpolation. As detailed in Figure 1, the workflow required three major steps.

3.1 Data sources

23 The data collection was organized using two categories of data sources (Figure 1).

Conventional data sources are provided by traditional statistical offices through census

for public, demographic use and policies. We gathered data from these providers

mainly to inform households income, and we used local income by national statistical

offices, and national income data at national level (Eurostat). We combine such classical

indicators with unconventional data sources to describe housing market.

24 Data were extracted from various platforms and sources and are often named “big

data”. We define as “unconventional” data sources that have not been designed and/or

documented to prepare measurements, geographical processing and socio-economic

research. They often derive from administration or commercial purposes. We

distinguish two kinds of unconventional data providers. Institutional data providers on

the one hand (Chambre des Notaires in France , Wuestpartner in Switzerland). Such

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

7

commercial providers distribute proprietary databases that derive from public records

of property transactions. They provide information on real-estate transactions. On the

other hand, we used scraped data from internet services, which gather advertisements

by real-estate agents and private sellers (Leboncoin in France, Fotocasa in Spain): the

database also aggregates information on real-estate offers. Such unconventional data is

often viewed as interesting proxies to measure, and better understand spatial

behaviors and territorial dynamics, and as a means of providing higher spatio-temporal

resolution data when compared to institutional data sources (Gallotti et al. 2015),

although findings suggests caution regarding the significance of such sources (Kitchin

2013). Prior to relying upon the unconventional data sources, it is important to assess

their reliability, and if they provide accurate information when compared to the long

established, statistically robust collection data. Some studies have addressed the

robustness of IDS (Internet Data Sources) compared to more conventional data (Le Goix

and Vesselinov 2014; Beresewicz 2015), so we also consider the issue of robustness of

collected samples in this study (section 3.6).

Figure 1: Overview of the methodology (workflow).

3.2 Spatial coverage: 10 functional urban areas as case-studies

25 Ten case studies have been selected, covering some of the variegated dynamics of

housing market (gentrification process, tourism, housing crisis, etc.). Highlighting

heterogeneous and contrasting situations has been deemed relevant to carry out a first

international and comparative study on housing dynamics in Europe based on local

indicators.

26 The 10 case studies cover 4 countries of the ESPON Area as well as one cross-border

region: Geneva-Annecy-Annemasse (Switzerland-France), Avignon and Paris (France),

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

8

Madrid, Barcelona and Palma de Majorca (Spain) and Warsaw, Łódź and Krakow

(Poland). They have been selected for their variety (size and urban dynamics), data

availability, and local expertise on data sources. Because they cover cities with both

high and low levels of owner-occupancy, the interest of the selection is to highlight a

range of housing regimes in Europe, and also allows to consider how to fill data gaps, as

on Figure 2 (Poland, for instance, was poorly documented in European databases).

27 The selected case studies occupy various positions in the urban hierarchy: the

spectrum ranges from 3rd tier cities functional urban areas (276,000 inhabitants for

Annecy, 320,000 for Avignon or 670,000 for Palma de Majorca), up to larger cities (3.1

million inhabitants for Warsaw, 4.9 for Barcelona, 6.6 for Madrid) and includes one

global city (11.9 M in Paris FUA). The Geneva-Annemasse-Annecy cross-border area

offers an interesting setting in terms of unequal affordability, not yet studied with

harmonized data.

28 For these 10 case-studies, the aim is to provide statistical information on housing

affordability at three territorial levels: at the FUA itself, and down to the LAU2 level

(communes in France) and the 1km European reference grid level.

Figure 2: Overview of case-study FUAs (% of owned dwellings 2010 and Eurostat’s data gaps).

Note : Names and blue outlines indicate case-studies (functional urban areas).

3.3 A survey of data sources for case studies

29 To detail the procedure, we have first identified the availability of possible sources to

analyze the local spatial structure of housing affordability in a selection of countries.

This step has highlighted how difficult it would be to follow a data-driven approach in a

European comparative perspective on housing and affordability. The goal has therefore

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

9

been to include in the study various national situations regarding the availability of

data, in order to test a methodology for data collection that could be extended to other

contexts, in a future pan-European study.

30 The review has been realized in France, Poland, Spain, Switzerland

3

, as main case

studies. Its purpose was to highlight the main characteristics of these data resources,

where local expertise was available (spatial coverage, time coverage, available

indicators…). We also used as source of information a recently published report by

Julliard and Gusarova (2019). Table 1 offers an overview of potential data sources

available for surveyed countries.

France has a long-standing well-established tradition of nationally collecting statistical

information on transactions. Given a costly fee (even for researcher of public institutions),

transaction data are made available commercially by the Paris Chamber of Notaries database

(BIEN). This database covers Ile-de-France real-estate transactions. For the rest of France,

the same type of information are commercially made available by French notaries as

PERVAL database. Such databases provide a wide range of information related to

transactions: price, very detailed characteristics of the property, as well as extra

information such as the socio-economic attributes of the seller and the buyer (age,

employment category), or the contracted debt of the buyer. Data on property values

declared to for land property taxation has been made available in 2019

4

. This fiscal database

(Demandes de valeurs foncières, DVF) is available free of charge. It however does not exactly

cover transactions on the housing markets, but individual parcels and buildings known

values. The problem being that one transactions is in many cases composed by several

parcels (i.e. one apartment and one garage; one house, a piece of land, and sometimes a

garage and an outbuilding). Major differences between transactions databases and DVF, and

their possible use, has been thoroughly documented by Casanova et al. (2017); Casanova

Enault, Boulay, and Coulon (2019). Furthermore, many online platforms coexist, that provide

different entry-points as IDS. We used one of the most popular ones: Leboncoin.fr market-

place advertises properties to buy and properties to let, either by real-estate agents or by

individuals

5

. InsideAirbnb (harvested Airbnb data) is also an important data source available

in Paris, Bordeaux and Lyon.

In Poland, a variety of datasets are available: for some cities the transaction price can be

obtained through notarial deeds, down to the address (Łódź), but this has not been the case

in Warsaw or Krakow. Some datasets are also collected by the National Bank of Poland (LAU2

units). The online real-estate market place domiporta.pl is a widely used resource, that

provides real-estate advertisement: it is a harvestable source for price asked and rent asked.

Airbnb advertises properties in many cities, but the insideAirBnb harvesting platform is not

available.

Except aggregated price index and statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE and

Ministerio des Fomento, Registradores de España), Spain has no national transaction

detailed local data widely and reliably available, although Registradores de España now

release partial data. Prices are not released publicly, however. Some cities publish their own

transactions data (Barcelonatran, for instance), otherwise price estimates are available

through companies and private providers. It is therefore convenient in Spain to harvest data

online: Fotocasa and Idealista are websites and interactive online platforms that collect

property advertisements. Such tools provide property and rental prices. InsideAirbnb

(harvested Airbnb data) is available for 6 Spanish cities: Madrid, Barcelona, Malaga,

Mallorca, Sevilla and Valencia.

•

•

•

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

10

Switzerland has official statistics on rents and new buildings (Census, Statistics Federal

Office), but not on property prices. Several private companies collect and distribute

property data for Switzerland, such as CIFI or Fahrländer Partner. In this project, we have

used Wuest&Partner data sources, considered as the most accurate.

Table 1: Potential data sources available for case studies, a synthesis

Countries Institutional data on transactions Market place platforms Census

(case study) (land registry, notaries…) (online data harvesting )

Switzerland X X

France X X

Spain Some cities X

Poland Some cities X

3.4 Data collection

31 Based on data sources identified, this section describes the process leading to the

combination of unconventional and conventional data sources. This process has been

fully documented, detailed as a narrative for the case study of Barcelona, along with

the complete R language code, to demonstrate and reproduce the methodology. A fully

documented reproducible R code is provided as Supplemental Material on the data

repository

6

. Other examples are documented in the full report

7

.

3.4.1 Conventional institutional data: Eurostat and National Statistical Institutes

indicators

32 A first issue is data collection from the relevant providers to target harmonized

indicators as outputs. Conventional census data are required to extract information at

EU level on socio-economic characteristics of case studies and to collect data on

income, for the construction of an estimation of real-estate affordability. Institutional

unconventional data are also required to describe residential property markets.

33 Two main categories of institutional data providers (“official statistics”) have been

used: harmonized European statistics and national statistics. EU statistics (sources

Urban statistics, Eurostat) have been used to characterize selected case-studies as

regards to the other cities of Europe. Taking into account the availability of data, 20

indicators at Core City have been identified, against 14 only at FUA level. This allows to

compare all the European cities and Functional Urban Areas. EU statistics include

demographic indicators (age), households’ characteristics, information related to the

employment (economy tertiary oriented or not) and other relevant factors to

understand who lives in the cities. However, little information is available on housing.

It is only possible to extract one item of the EU perception survey: “is it easy to find

good housing in your city?”, which gives only a very rough qualitative assessment of

affordability by European citizens. These indicators are provided in the data repository.

•

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

11

Table 2: Listing of Eurostat available indicators relevant for characterizing the housing market

ID

Indicator Name

Reference

year

Reference

(in the data delivery)

(Eurostat

table)

POP_2015 Total population 2015 “urb_cpop1”

POP024_2015 Share of population aged 0-24 years (%) 2015 “urb_cpop1”

POP2544_2015 Share of population aged 25-44 years (%) 2015 “urb_cpop1”

POP4564_2015 Share of population aged 45-64 years (%) 2015 “urb_cpop1”

POP65_2015

Share of population aged above 65 years

(%)

2015 “urb_cpop1”

HOUSEHOLD_AREA_2011 Housing size (average size of dwellings) 2011 “urb_clivcon”

HOUSEHOLD_SIZE_2011 Average size of households 2011 “urb_clivcon”

SINGLE_HOUSEHOLD_2011 Share of single households (%) 2011 “urb_clivcon”

OWNED_DWELLINGS_2011 Share of owner-occupied dwellings (%) 2011 “urb_clivcon”

UNEMP_2014 Unemployment rate (%) 2014 “urb_clma”

EMP_INDS_2014 Share of employment in industry (%) 2014 “urb_clma”

EMP_HOTELS_2014

Share of employment in restauration,

hotels and transports (%)

2014 “urb_clma”

EMP_RESTATE_2014

Share of employment in real estate

activities (%)

2014 “urb_clma”

ST_HIGH_EDU_2011

Share of students in higher education

(ISCED 5-6) (per 1000 persons in the

population 18-24 years)

2011 “urb_ceduc”

WF_HIGH_EDU_2011

Proportion of popuation aged 25-64 years

qualified at level 5 to 8 ISCED

2011 “urb_ceduc”

NIGHTS_2011

Total nights spent in tourist

accommodation establishments per

resident population

2011 “urb_ctour”

BEDS_2011

Number of available beds in tourist

accomodation establishments per 1000

residents

2011 “urb_ctour”

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

12

HOUSING_EASY_2015

Share of persons answering "Strongly

agree" to the question of the Urban Audit

: is it easy to find good housing in your

city ?

2015 “urb_percep”

HOUSING_DIFFICULT_2015

Share of persons answering "Strongly

disagree" to the question of the Urban

Audit : is it easy to find good housing in

your city ?

2015 “urb_percep”

34 Global affordability indices have been prepared using European income data at a

national level (EU-SILC survey

8

). This is the reference source for comparative statistics

on income distribution in the European Union. For this study, the first, the fifth

(median) and the ninth decile of income distribution have been used. The choice of

thresholds has been made with regards to the needs for data standardization to

compare national affordability between case studies in the local data production

described in the following subsections. These aggregates, harmonized at a European

level, allow the comparison of affordability levels across national contexts. Income data

have then been used to produce normalized indicators of affordability (price to income

ratio), for instance to answer the following question: “How long the 10% poorest /

median / 10% richest of the population have to work to buy/rent 1sq. meter in city A”?

35 LAU2 income, data provided by national providers, have also been used, especially to

locally contextualize affordability. A classical caveat applies regarding income data. It

is not recommended to compare local affordability, based on local income data,

between cities of different countries. Indeed, the methodologies for income

computation varies from one country to another: per capita or per households; before/

after tax; with or without social benefits, etc. The statistical parameters for aggregated

income also differ in institutional data, some as median, other are average income at

LAU2 level. Nevertheless, local affordability indexes are still highly relevant to compare

local affordability between cities of the same country (Avignon-Paris / Madrid,

Barcelona-Palma de Mallorca / or Łódź-Warsaw-Krakow separately), the methodology

of income calculation being generally harmonized at national level. Indicators available

in the database are detailed section 3.5.3.3.2 Unconventional institutional data:

transactions

36 In some cases, in France, it has been possible to use property-level data. Two datasets

have been used.

One on the Paris region, provided under the Labex Dynamite agreement by Paris Notaries

Services, a subsidiary of the Chamber of the Notaries. This sample contains transactions for

the region and its suburbs, within the administrative limits of Ile-de-France (roughly 1

million rows), for year 1996 to 2012. All records contain information on the property

amenities and pricing, and series of understudied interesting variable on sellers and buyers,

such as age, sex, socio-economic status, national origin, place of residence, and some credit

history related to the transaction. For a discussion on the interest and limitations of this

dataset for local studies of housing inequality, see Le Goix et al. (2019a).

In other French FUAs (Avignon, Annecy, Annemasse), PERVAL, a database of transactions

provided by Les notaires de France has been purchased for the study. It provides properties

•

•

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

13

information, based on individual transactions, with a data structure similar to BIEN

database.

3.4.3 Unconventional real-estate data: harvesting

37 Data harvesting or web-scraping has been systematically used to gather data on the

real-estate market offer (both property and rental markets), where institutional data

on transactions simply do not exist. Harvesting real-estate websites can be considered

in such cases as the only viable solution to properly gather a significant sample of data

on housing market and advertised prices on real estate offers or rental. Data harvesting

however raises methodological, ethical and legal questions that have been considered

in the course of the project.

9

38 Data harvesting, on real-estate advertisement websites and market-places platforms

has been conducted following a procedure, generally using Python language Scrapy

library, which can be summarized as follows:

Listing properties. Harvesting real estate online listings (property advertisements). It

consists in getting the total number of ads and determining the pages to scrape after

identification of the relevant tags syntax in the URL query, with a specific attention given to

geographical tags and the type of offer (real estate offer / rental ; apartments and-or houses,

etc). We then automatically collect all the adds included in all pages of the first query result.

The first output is a list of URLs to be harvested (one URL by offer).

Identifying all the relevant information for listed properties in step 1. This consists in

preparing the script for each website to automatically fetch the data. It requires to harvest

the webpage, and identify the interesting attributes/tags to get (price, number of rooms,

surface, geographical location …). This is a tedious, very costly and time-consuming process

that requires a lot of retro-engineering of webpages, with different data sources in each

countries

10

.

Data cleaning. The most common errors are duplicate records (sometimes a real estate

listing can be published several times), absence of location coordinates or inconsistencies in

the information describing each advertised property (area, price, etc.). More inconsistencies

are found in geocoding. This will be further discussed in the validation section.

3.5 Harmonization of the database, description of variables

39 Data collection/cleaning and aggregation procedures are conducted so as to produce

data that can be used in a multiscale perspective. Produced at the local fine-grain

geographical city level (grid and LAU2), they are also aggregated up to the level of the

entire FUAs. The indicators created are described below, and summarized Table 3.

40 Local data produced contain the following information, where available:

Official geometries identifiers (LAU2 and grid)

Income data (municipal and national income data)

Aggregated transaction data if available (rooms, surface, price, debt contracted)

Aggregated web-scraped data for property sales (rooms, surface, price)

Aggregated web-scraped data for property rental (rooms, surface, price)

41 The production of indicators revolved around the premises that price-to-income ratios,

and their derivatives, are a commonly agreed characterization of general affordability.

There are many dimensions to define affordability and accessibility to housing, a

simple and robust indicator had to be defined and our proposal elaborates on price-to-

1.

2.

3.

•

•

•

•

•

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

14

income ratio, a measure often considered in the literature (Kim and Renaud 2009; Tighe

and Mueller 2012; Friggit 2017). One of the advantages is how this measure combines

housing prices (ownership or rental) as a numerator and a denominator related to

wealth or socio-economic situation of the population (income). PIR are easy to

understand and convey clear policy data informed messages, such as the number of

months of full-time wage required to buy or rent 1 square meter

11

.

42 The database delivers 29 targeted indicators at the FUA level, relevant for discussing

housing and compare characterization between FUAs. These are provided at LAU2

level. It corresponds to 1390 territorial units in the Paris FUA, 43 in Avignon, 286 in the

Geneva cross-border Area, 129 in Barcelona, 137 in Madrid, 33 in Palma de Mallorca,

151 in the 3 Polish FUAs. Data have also been aggregated at the FUA levels to provide

statistical synthesis at this territorial level highly important from a policy point of view

in Europe

12

.

43 The indicators cover all the dimensions of the data collection, meaning real-estate

transactions (Table 3a), real-transaction offers (Table 3b), the level of income of the

population (Table 3c) and harmonized indicators (Table 3d, based on the variables

detailed in Tables 3a,b and c). Metadata explicitly detail the indicator codes, labels,

units of measure, reference year and data sources.

44 For each of the indicators displayed in table 3a and 3b, several statistical distribution

parameters have been used as thresholds to evaluate the statistical dispersion at the

LAU2 territorial unit

13

: first quartile (Q25 in the indicator code), median (Q50), third

quartile (Q75), sum.

Table 3a: Indicators on real-estate transactions

Code Label Measure unit Reference years

TRANS_NUMBER

Number of real

estate

transactions

(apartments)

Number of

transactions

2011-2012 (Paris), 2010 and 2014 (Avignon),

2017 (Polish case-studies), 2012 (Barcelona),

2010 and 2015 for Geneva cross-border area,

no data for Madrid and Palma de Mallorca,

Debt is only available for French case-

studies.

PRICE_PAID

Price paid for

properties

Euros

SURFACE

Surface of

properties

Square

meters

ROOMS Number of rooms Room

DEPT_SUM

Sum of debt

contracted to buy

a property

Euros

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

15

Table 3b: Indicators on real-estate offers

Code Label

Measure

unit

Reference year

OFFERS_NUMBER

Number of real estate

offers

Number of

offers

Data gathered from Web scraping on

reference real-estate Websites in

2019.

OFFERS_PRICE

Advertized price for

properties (real estate

offers)

Euros

OFFERS_SURFACE

Surface of properties (real

estate offers)

Square

meters

OFFERS_ROOMS Number of rooms Room

RENT_NUMBER Number of rental offers

Number of

offers

RENT_PRICE

Advertized price for rental

offers

Euros

RENT_SURFACE Surface of rental offers

Square

meters

RENT_ROOMS

Number of rooms (rental

offers),

Room

RBNB_NUMBER Number of Airbnb offer

Number of

offer

2019 (Inside Airbnb)

Table 3c - Indicators from national statistical censuses and Eurostat

Code Label

Measure

unit

Reference year

TOT_P Total population Inhabitants 2011

INCOME_LOC

Average or median

income (municipalities)

Euros

2016 for France, 2015 for Poland,

2011-2015 for France and Switzerland

(average on time-period),

INCOME_NAT_D1

National Income, first

decile

Euros 2015

INCOME_NAT_D5

National Income,

median

Euros 2015

INCOME_NAT_D9

National Income, 9th

decile

Euros 2015

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

16

45 The most relevant ratios (Table 3d) are combined starting from basic indicators (Tables

3a,b & c).

price/sq. meter (price paid, advertised price, rental), a standard indicator, but highly

contingent to the local structure of housing;

Three different affordability indices. Local affordability is a price-to-income ratio computed

with local income. It describes to what extent a LAU2 is more or less affordable for

household living in the LAU2, based on the local income distribution. National affordability

answers a more general question: to what extent a given place is affordable for an average

household in a given country. We also provide the difference between local and national

affordability. This gives a better understanding of whether it is easier or not for a local

household, as compared to another one moving out from any other place in the same

country, to afford a property in the designated area (positive values), or not (negative

values).

A last index is referred to as the profitability index, calculated as a ratio between advertised

price for property and advertised price for rental. This approach is best conceptualized as

being a common approach that computes how much one landlord should invest in a rental

property for 1 euro of rent”. A higher index means two things: advertised prices are high, as

compared to rental offer; or rental offer prices are cheaper, compared to property prices. In

other terms, a lower index can be interpreted as locations where the development of rental

offers may be specifically profitable for real-estate investors.

Table 3d - Synthesis of harmonized indicators built from various data sources.

Code Label

Measure

unit

Based

on,

PRICE_SURF Price paid for properties

Euros per

square

meters

A

OFFERS_PRICESURF Advertized price for properties,

Euros per

square

meters

B

RENT_PRICESURF Advertized price for rental offers

Euros per

square

meters

B

PROFIT

Profitability index (Ratio between advertized

price per sq. meter for property and advertized

price per sq. meter for rental offers

Index B

TRANS_SQ_METERS_LOC

Local affordability: Number of months of local

income required to buy 1sq. meter (ratio

between price paid per sq. meter for property

and median local income/12)

Month A-C

•

•

•

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

17

TRANS_SQ_METERS_NATD5

National affordability: Number of months of

national income required to buy 1sq. meter

(ratio between price paid per sq. meter for

property and median income/12)

Month A-C

TRANS_SQ_ METERS_DIFF

Difference between local and national

affordability (transactions)

Month D

BUY_SQ_METERS_LOC

Local affordability (real-estate transaction

offers)

Month B-C

BUY_SQ_METERS_NATD5

National affordability (real-estate transaction

offers)

Month B-C

BUY_SQ_ METERS_DIFF

Difference between local and national

affordability (transaction offers)

Month D

RENT_SQ_METERS_LOC

Local affordability (rental): Number of days of

local income required to rent 1sq. meter (ratio

between advertized price per sq. meter for

rental and median local income/365)

Days B-C

RENT_SQ_METERS_NATD5

National affordability (rental): Number of days

of national income required to rent 1sq. meter

(ratio between advertized price per sq. meter

for rental and median local income/365)

Days B-C

RENT_SQ_METERS_DIFF

Difference between local and national

affordability (rental)

Days D

PRICE_SUM_SM

Price paid for properties, sum, smoothed (cf

part 3.5.2 for details)

Euros A-B

SURFACE_SUM_SQ

Surface of properties, sum, smoothed (cf part

3.5.2 for details)

Square

meters

A-B

PRICE_SQ_SM

Price paid for properties (Euros per square

meters), smoothed

Euros /

square

meters

D

46 Considering the availability of data, and combining data with the computation of

statistical parameters (Q25, Q50, Q75, etc.) whenever it was deemed relevant, the

database is structured with 84 variables for the FUA of Paris, 83 for Geneva-cross-

border area, 108 for Avignon (real-estate transactions available for 2 time periods), 56

for Madrid and Palma de Mallorca (no real-estate transaction data), 79 for Barcelona

(some real-estate transaction indicators) and 63 indicators for Poland. All variable

names share a common coding system, whenever the datasets are fully comparable

from a methodological point of view. The data repository includes one data file by case-

study.

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

18

3.6 Quality control and data validation

47 Two main issues had to be tackled with when analyzing the consistency of data

produced. A first one has been the degree to which it was statistically reliable to match

institutional and robust census data with scraped and maybe biased datasets. A second

issue was how to address missing values, locally poor sampling of spatial data, and

spatial biases. This section describes how such issues have been tackled with, and

mitigation procedures that have been applied and approved by ESPON EGTC, in the

process of publishing the datasets on ESPON Database Portal.

3.6.1 Quality of scraped data vs. institutional data

48 The reliability of ‘big data’ when compared to institutional sources is indeed a complex

question which does not have a single and clear answer. Some research focused on

assessing the sampling bias of various ISP data sources, whether socio-demographics or

spatial coverage quality assessment – i.e. statistical and spatial representativeness

(Ruths and Pfeffer 2014; Longley, Adnan, and Lansley 2015; Shelton, Poorthui, and Zook

2015). Such studies have been conducted on a case-by-case basis, and this literature

lacks references to quantitatively review, for a given spatial information task, the pros

and cons of different types of big data when compared to traditional sources, by

systematically comparing the picture one obtains with different sources.

49 To avoid this lack of comparison between pricing references, we designed our research

so as to be able to estimate the quality of scraped data, elaborating on researches that

have conducted estimations and quality control on similar data sources. First, 2006

Beresewicz (2015) specifically addresses the question of comparing the

representativeness of Internet Data Sources (IDS) compared to conventional data

sources to analyze the real estate market in Poland. Institutional database on

transactions allows to compare with harvested big data sources (real estate websites,

open data sources and warehouses, Airbnb…). He also evaluates to which extent such

online resources can be considered reliable to estimate quantitative information of the

housing market. He compares basic variables, such as price per sq. m, floor area,

number of rooms, to verify the consistency of data between institutional data and IDS.

This research found the IDS data sources to be mostly consistent over time, except for

larger apartments which are under-represented. He finally insists on the fact that "due

to the non-sampling character of data obtained from the Internet, it is challenging to

estimate standard errors for the estimated characteristics», and that transactions

institutional data "do not contain any information on standard errors of estimates,

which again limits the scope of comparison of distributions" (2006, p. 54).

50 We obviously faced similar issues. We therefore sought to estimate the differences in

datasets by comparing the statistical distribution of those constructed with

institutional sources on the one hand, and those gathered by the means of real-estate

website harvesting, for case-studies for which both sources were available. Elaborating

on a very common indicator, price per sq. meter. Figure 3 shows that there are

significant differences between institutional data and IPS data, especially in Avignon,

Paris and Barcelona. Geneva, Annecy and Annemasse ISP data however seem to better

fit the distribution of transaction data. We also plot on Figure 3 the distribution of price

per sq. meters for case-studies for which only harvested data from ISP: it has not been

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

19

possible to compare ISP data to other sources in these cases (Madrid, Palma and

Warsaw, Łódź and Krakow).

Figure 3: Statistical distribution of case-studies in the ESPON Housing database, and sample

difference analysis where both institutional and scraped ISP sources available: Kruskal-Wallis test

and Dunn pairwise tests significance. Significant differences between groups shown only. Name of

variables are the same as in the distributed database (boxplots: Q1, Q2 and Q3. error bars: 1.5*IQR.

point: means).

Source: ESPON Big Data for Territorial Analysis and Housing Dynamics, UMS RIATE, 2019

51 To elaborate further on the differences between data sources, and to document

whether scraped data should be used assuming they are representative as an

alternative data source, we assume that scraped data have in common a non-sampling

character. Recent work also analyzed available data and possible bias and

representativeness issues (Boulay G., Blanke D., Casanova Enault L., and Granié A.,

2020). They showed that transaction data (where available, for instance in France) do

not contain any information on standard errors of estimates, which limits the scope of

comparison between statistical distributions. They compared, on the one hand, DVF

and PERVAL databases, both released as transaction database, the first one being

produced for fiscal purposes, the other one as a listing of transactions registered by the

Chamber of the Notaries. On both sources, they noted the non-sampling character of

data, notaries listing being incomplete (especially outside of the Paris region)

14

, and

DVF data being reconstructed as pseudo-transactions after post-processing arbitrages

conducted on records that describe parcels (many of them with multiple units, i.e.

several apartments; or any combination of houses, apartments, commercial units).

They conclude that fiscal data and notaries data do not exactly convey the same

representation of pricing and market segments. More importantly, they insist that

public records made available as open-data (Open-DVF) do not allow to analyze the

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

20

volume of transactions, neither to easily distinguish new housing units, against stock

housing units (Casanova Enault et al., 2019). Casanova et al. (2017) importantly

conclude that discrepancies observed between DVF and PERVAL derive from "1) the

sampling biases induced by the incomplete and unknown coverage of the market in the

PERVAL database, 2) differences in choice in the segmentation applied to DVF (post-

processing of multiple transactions in parcel records)" (Casanova et al., 2017, p. 726,

Author’s translation).

52 To illustrate this point, we analyzed data gathered with different sources for the

Avignon FUA (Figure 4) and the Paris FUA (Figure 5). Both are functional urban areas

for which both institutional data (transactions from the notaries) and scraped data

(advertisements) were available for the study. Additionally, to better inform the

validity of collected data, we used DVF fiscal data (the Etalab version), a dataset that

was not available at the time of the study delivered to ESPON. We however used DVF in

this paper because records are exhaustive, and are useful to benchmark the quality of

scraped data against public records. Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the resulting

distribution comparisons (box plots), a Kruskal-Wallis test and a pairwise Dunn test.

Although box-plots demonstrate on average similar distribution patterns of means,

median, Q1 and Q3 across the samples compared, the Kruskal-Wallis test demonstrates

that distributions significantly differ one from another, and this is especially true with

the number of rooms, which seems unreliable in scraped data, compared to other

datasets. The pairwise comparison shows that transactions and fiscal data, although

different, are also in general more similar in Avignon. In Paris FUA, all databases show

significant differences in means, for every variable. Scraped data 2019 and BIEN 2012

however show similar means, and the pairwise test does not allow to reject the null

hypothesis. Such a similarity in means and median is counter intuitive, given the

tremendous effect of inflation in Paris. Interpretation of the result is therefore

speculative, because of the lack of comparability of price references between BIEN and

DVF (Casanova Enault et al., 2019; Casanova et al., 2017). A probable elaboration on the

result would be that while the central city has maintained price growth in the upper

segments of price/sq meters brackets, the rest of the metropolitan area has not

followed up on the inflation curve: as a consequence Q3 and the upper 1.5 IQR

threshold are much higher in 2019 than in 2012, and price inflation has increased

heterogeneity in the statistical distribution of prices at the level of the entire FUA.

53 From this, it seems inappropriate to conclude that scraped data are representative of

institutional data as an alternative data source, because of uncontrolled bias in all three

data sources, that affects the pairwise comparison of data. Especially, scraped data,

based on advertised transactions, are characterized by a higher variance, especially

regarding the advertised price and surface, and outliers that are difficult to control for

their reliability (possible errors on posted properties listings). It can be assumed that

errors on price, surface and number of rooms are limited when controlled and recorded

with the signature of the final deed

15

.

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

21

Figure 4: Sample difference analysis of transactions and advertisements, data sources on Avignon

FAU (PERVAL, DVF, Scraped data) : Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn pairwise tests significance.

Significant differences between groups shown only. (boxplots: Q1, Q2 and Q3. error bars: 1.5*IQR.

point: means).

Sources: PERVAL 2010, 2014 ; DVF 2019; LeBonCoin 2019

Figure 5: Sample difference analysis of transactions and advertisements, data sources on Paris

FAU (BIEN, DVF, Scraped data) : Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn pairwise tests significance.

Significant differences between groups shown only. (boxplots: Q1, Q2 and Q3. error bars: 1.5*IQR.

point: means).

Sources: BIEN 2010, 2012 ; DVF 2019; LeBonCoin 2019

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

22

3.5.2 Spatial coverage and missing data: interpolation

54 All indicators have been delivered at the LAU2 level. But some indicators have also been

delivered at a finer grain. We describe the interest and methodology required to go

beyond the municipal level by aggregating and interpolating the results in a 1km

INSPIRE grid. This allows to go beyond the LAU2 level which, although relevant for

policy making, is basically too large for observing existing inequalities for some cities

defined by large territorial units, such as Paris, Barcelona or Warsaw. Indeed, larger

geographical aggregates (LAU2) poorly perform when it comes to circumscribe the

local structure of housing markets and living conditions, because of the local

heterogeneity of local spatial patterns. Local submarkets, segments and regimes are

often constructed at more local geographical levels, and grid cells have often been

considered an ad hoc solution to provide a more detailed analysis when disaggregated

data sources are available.

55 We followed the approach that has already been applied in the case of transactions

(Guérois and Le Goix 2009; Le Goix et al. 2019). It consists in computing a synthetic

value based on distance and weight of the observed population, as initially proposed by

Stewart (1942) for an analysis of the distribution of student population and catchment

areas of American Universities, and more recently applied for socioeconomic

phenomena (Grasland 2009). We infer that property markets are discrete social data,

similar to Tobler’s hypothesis (Tobler and Wineburg 1971): a potential price for a

specific location is a function of distance to nearby similar transactions, and also a

function of the number of properties available, turnover and realized transactions. This

method removes spatial bias, resolving the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP). We

apply Stewart’s potential to house price, and also to the number of sellers and buyers of

each occupational category, using the SpatialPosition R package (Commenges and Giraud

2016; Commenges, Giraud, and Lambert 2016). Resulting values have been estimated

negative exponential function, with a span of 5 km and a distance decay parameter of

-2. An example of the resulting visualization is provided in Figure 6.

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

23

Figure 6: Property values in Barcelona, estimations at a 1 km grid cell (Advertized price per sq. m.)

4 Use and possible reuse: some insights on comparing

affordability indicators between cities

56 We present maps and discuss some examples of the findings for a selection of FUAs, to

highlight the different ways data from the ESPON Housing database can be used and

compared to analyze some dimensions of affordability, for both the rental and property

buyers’ markets.

4.1 Comparing advertised rental prices

57 A first set of examples, in Poland, shows how the case cities (FUAs) reflect divergent

paths of demographic and economic development in the last three decades, with

dynamics regions i.e., Krakow and Warsaw, and on the other hand Łódź that became

one of the fastest shrinking cities in Poland. On Figure 7, we compare the price of rental

(scraped data), and the median national income. To clarify, the idea underlying the

reference to national income being to what extent is it possible for a median household,

living anywhere in Poland, to access affordable housing in any given neighborhood, in

any city.

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

24

Figure 7: Affordability (rental) – national income, 2019 (Warsaw, Łódź, Krakow)

58 The maps display the time required (number of days of median income) to rent 1 sq. m.

The level of housing affordability generally reflects the geography of real estate offers,

with lower availability in the municipalities with more expensive offers for sale and

rental housing. Intriguingly, it is difficult to distinguish one common pattern for the

three case cities/regions. Whereas in the Krakow region the lowest housing

affordability (sales and rentals) characterizes the core city, suburban locations also

show high rent-to-income ratio (low affordability) in Łódź and Warsaw. The lower

housing affordability in some suburban municipalities is related to the relationship

between the relative low incomes of the population that stay put, and the new wave of

suburbanization bringing new housing further away from the core city. The patterns of

housing affordability do not precisely fit the expected distance decay from the center,

but is rather spatially structured within the three functional urban areas following a

mosaic or fragmented structure; and some clusters of high and low values could also be

distinguished.

4.2 The multifaceted aspects of affordability issues in Paris

59 Another example of how we approached affordability can be covered with those three

maps of the Paris FUA, a housing market that is considered very strong, tensed and

highly unaffordable for local residents (Figure 9).

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

25

Figure 8: The variegated dimensions of affordability in Paris.

Note : a. the number of months of local income required to buy 1 sq. Meter. b. the number of days of

local income to rent 1 sq.meter. c. the number of months of income to buy 1 sq. m., on the basis of

French national income median. d. the difference of purchasing power in Paris in local income

compared to national income (a minus c).

60 The spatial structure of affordability shows very contrasted patterns in Paris, and this

example offers an opportunity to highlight different ways of measuring affordability,

with contrasting results.

Affordability measured with reference to local income shows that buying an apartment

downtown Paris will cost at least 3.8 months of full income by sq. meter, this is not true in

the wealthiest part (16th arrondissement), where local income offset the cost of housing.

This analysis of unequal affordability is strongly driven by the effects of local income: with

lower income in the North-East of the FUA, the structure of housing is more and more

inaccessible to local residents (Figure 8a).

Rental affordability, when compared to local average income at the municipal level (Figure

8b) is highly detrimental to the population leaving in the Nord-East corridor of Paris, and

generally speaking in the lower income areas of the East side of the inner suburbs.

Analysis of affordability with reference to the national median income tells a different story:

the entire western corridor is very unaffordable on this index (above the threshold of 2

months of income by sq. m.), while the North-East and South-East sections of the FUA

correspond to areas where apartments would cost between 0.8 to 1.8 months / sq. m.

On Figure 8d, data show what can be described as a differential accessibility, in other words

the difference in purchasing power between national and local municipal incomes. This

represents the difference between the financial effort of a local resident compared with the

financial effort of an outsider willing to move in. While most of the Western side is rather

unaffordable (purple), and out of reach for an average household based on national income,

part of the region in yellow remains more or less affordable to an average household, while

•

•

•

•

Unequal housing affordability across European cities. The ESPON Housing Datab...

Cybergeo : European Journal of Geography , Data papers

26

it is not affordable to local residents. This price-to-income spatial structure highlights how

property markets pressurize the potential of ownership and decent access to housing in the

inner ring of the region, in former blue-collar and now gentrifying neighborhoods

especially.