Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research

Strategic Plan 1997

by

Norman B. Anderson, Ph.D

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

National Institutes of Health

Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research

Publication Number 97-4237

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword...........................................................................................Page 4

Preface..........................................................................................,...Page 5

Section One: Introduction...............................................................Page 6

The Need for Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at the National Institutes of Health

Mandates and Responsibilities of the OBSSR

The Philosophy of, and a Vision for the OBSSR

The Strategic Planning Process

Overview of the Strategic Plan

Section Two: The OBSSR Strategic Plan.......................................Page 14

Goal 1: Enhance behavioral and social sciences research and training

• Capitalize on scientic opportunities in behavioral and social research across NIH

• Enhance behavioral and social research in the NIH Intramural Research Program

• Increase training opportunities in behavioral and social sciences research

• Highlight the contributions of behavioral and social sciences research to the

improvement of health

• Increase the visibility of behavioral and social sciences within the NIH community

Goal 2: Integrate a biobehavioral interdisciplinary perspective into all NIH research area

• Increase communication and cooperation between sociobehavioral and biomedical re

searchers

• Increase inter-disciplinary training opportunities

• Create interdisciplinary funding initiatives

• Increase the visibility of behavioral and social sciences within the NIH community

Page 2

Goal 3: Improve communication among scientists and with the public

• Establish communication links between OBSSR and the behavioral and social

sciences community

• Disseminate behavioral and social science research ndings to the public and to practi-

tioners

• Improve media coverage

• Increase communications and cooperation between sociobehavioral and biomedical

researchers

• Increase visibility of behavioral and social sciences within the NIH community

Section Three: Appendices..........................................................Page 22

Appendix A: OBSSR STRATEGIC PLANNING MEETING ORGANIZING COMMITTEE

Appendix B: PARTICIPANTS IN OBSSR STRATEGIC PLANNING MEETINGS

Page 3

Forward

In 1993, the United States Congress established the Office

of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR) at the

National Institutes of Health (NIH). The NIH has a long history of

funding health-related behavioral and social sciences research,

and the results of this work have contributed signicantly to our

understanding, treatment, and prevention of disease. Indeed,

much of our recognition of the health risks associated with

smoking, physical inactivity, alcohol and drug abuse, poverty,

and unhealthy diets is the result of NIH-funded research.

The establishment of the OBSSR furthers the ability of the

NIH to capitalize on the scientic opportunities that exist in

behavioral and social sciences research, thereby increasing

the effectiveness of the NIH as a whole. In addition, the office

provides a focal point for the coordination of trans-NIH activities

on health and behavior.

The OBSSR officially opened on July 1, 1995, following my

appointment of Dr. Norman Anderson as its rst director. In its

two years of operation, the office has effectively highlighted the

intellectual excitement and scientic opportunities that exist in

behavioral and social sciences research and has emphasized

its potential to advance public health. Because the office is

relatively new to the NIH, it is important for it to have a blueprint

for accomplishing its goals. The strategic plan outlined in this

document provides such a blueprint, and should help to ensure

the continued success of the office.

I would like to express my sincere thanks to the OBSSR, and

to the scientists and administrators who worked to develop this

plan.

Harold E. Varmus, M.D.

Former Director, 1993-1999

National Institutes of Health

Page 4

Preface

As the rst Director of the Office of Behavioral and Social

Sciences Research (OBSSR) at the National Institutes of

Health (NIH), it is my pleasure to present the rst OBSSR

Strategic Plan. This plan is designed to guide the office’s

activities for the next three to ve years. The development

of this plan was a multifaceted process, initiated by two

meetings in February and March of 1996 with over 70

scientists and administrators. These meetings generated

hundreds of recommendations that were reviewed and

consolidated by the OBSSR staff, from which a draft plan

was developed. This draft was then sent for comment to

the governing boards of over 20 scientic societies, and

to the NIH Behavioral and Social Sciences Coordinating

Committee. Finally, the plan was then revised based on the

comments of these groups.

I would like to express my appreciation to the many

scientists and administrators who participated in our

strategic planning meetings, and whose work is reected

in this document (see list of participants at the appendix).

I would also like to thank the OBSSR staff for its diligence

throughout this process, and our consultants, John Bryson

and Charles Finn, whose expertise in strategic planning

was critical to the success of this initiative.

Norman B. Anderson, Ph.D

Founding Director, 1995-2000

Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research

August 1997

Page 5

Section One: Introduction

Norman B. Anderson, Ph.D.

Director, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research

and Associate Director, National Institutes of Health

1. We need to

identify new behav-

ioral and social risk

factors.

The Need for Behavioral and Social Sciences Research

at the National Institutes of Health

The mission of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is to fund and

conduct research that will improve the health of the public. Congress es-

tablished the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR)

at the NIH to facilitate the growth and development of these important

elds. The creation of the OBSSR was in part a recognition that behavioral

and social factors are not only signicant contributors to health and illness,

but frequently interact with biological factors to inuence health outcomes.

In addition, it was recognized that behavioral and social factors represent

important avenues for treatment and prevention.

To further the mission of the NIH, four areas of behavioral and social

sciences research must be expanded.

1. We need to identify new behavioral and social risk factors for disease.

Behavioral and social sciences research funded by the NIH has contribut-

ed to the discovery of such well-known risk factors as cigarette smoking,

high-fat diets, physical inactivity, substance abuse, low socioeconomic

status and many others. Yet, there are unquestionably other behavioral and

social potential risk factors for illness that await discovery.

Page 6

3. We must develop

new behavioral and

social treatment

and prevention ap-

proaches.

4. We need more

basic behavioral

and social sciences

research.

2. We need more

research on

biological, behavior-

al, and social

interactions. We

need more research

on biological, be-

havioral, and social

interactions.

2. We need more research on biological, behavioral, and social interactions

as they affect health. It has already been discovered, for example, that

psychological stress can impair brain development, elevate blood pressure,

suppress immune system functioning, and contribute to coronary occlusion.

The hallmark of research on biopsychosocial interactions has been interdis-

ciplinary collaboration, and these efforts must be expanded.

3. We must develop new behavioral and social treatment and prevention

approaches. Directing more attention to such approaches will allow us to

continue on the remarkable progress that has already occurred in the treat-

ment and prevention of an array of disorders such as depression, heart

disease, chronic pain, infant mortality, and AIDS.

4. We need more basic behavioral and social sciences research to acceler-

ate advances in such areas as learning and memory, emotion, motivation,

perception, cognition, social class, social relations, family processes, and

cultural practices. Such research is the foundation for all other behavioral

and social sciences research.

Page 7

Mandates and Responsibilities of OBSSR

The OBSSR officially opened on July 1, 1995. The major responsibilities of the office and its

director, as mandated by Congress, may be summarized as follows:

• to provide leadership and direction in the development, renement, and implementation of

a trans-NIH plan to increase the scope of and support for behavioral and social sciences

research;

• to inform and advise the director of NIH and other key officials of trends and developments

having signicant bearing on the missions of the NIH, Department of Health and Human

Services, and other Federal agencies;

• to serve as the principal NIH spokesperson regarding research on the importance of behav-

ioral, social, and lifestyle factors in the initiation, treatment, and prevention of disease; and

to advise and consult on these topics with NIH scientists and others within and outside the

Federal Government;

• to develop a standard denition of “behavioral and social sciences research,” assess the

current levels of NIH support for this research, and develop an overall strategy for the uniform

expansion and integration of these disciplines across NIH institutes and centers;

• to promote cross-cutting, interdisciplinary research, and to integrate a biobehavioral perspec-

tive into research on the promotion of good health, and the prevention, treatment, and cure of

diseases;

• to develop initiatives designed to stimulate research in the behavioral and social sciences;

• to ensure that ndings from behavioral and social sciences research are disseminated to the

public;

• to sponsor seminars, symposia, workshops, and conferences at the NIH and at national and

international scientic meetings on state-of-the-art behavioral and social sciences research.

Page 8

The Philosophy of, and a Vision for the OBSSR

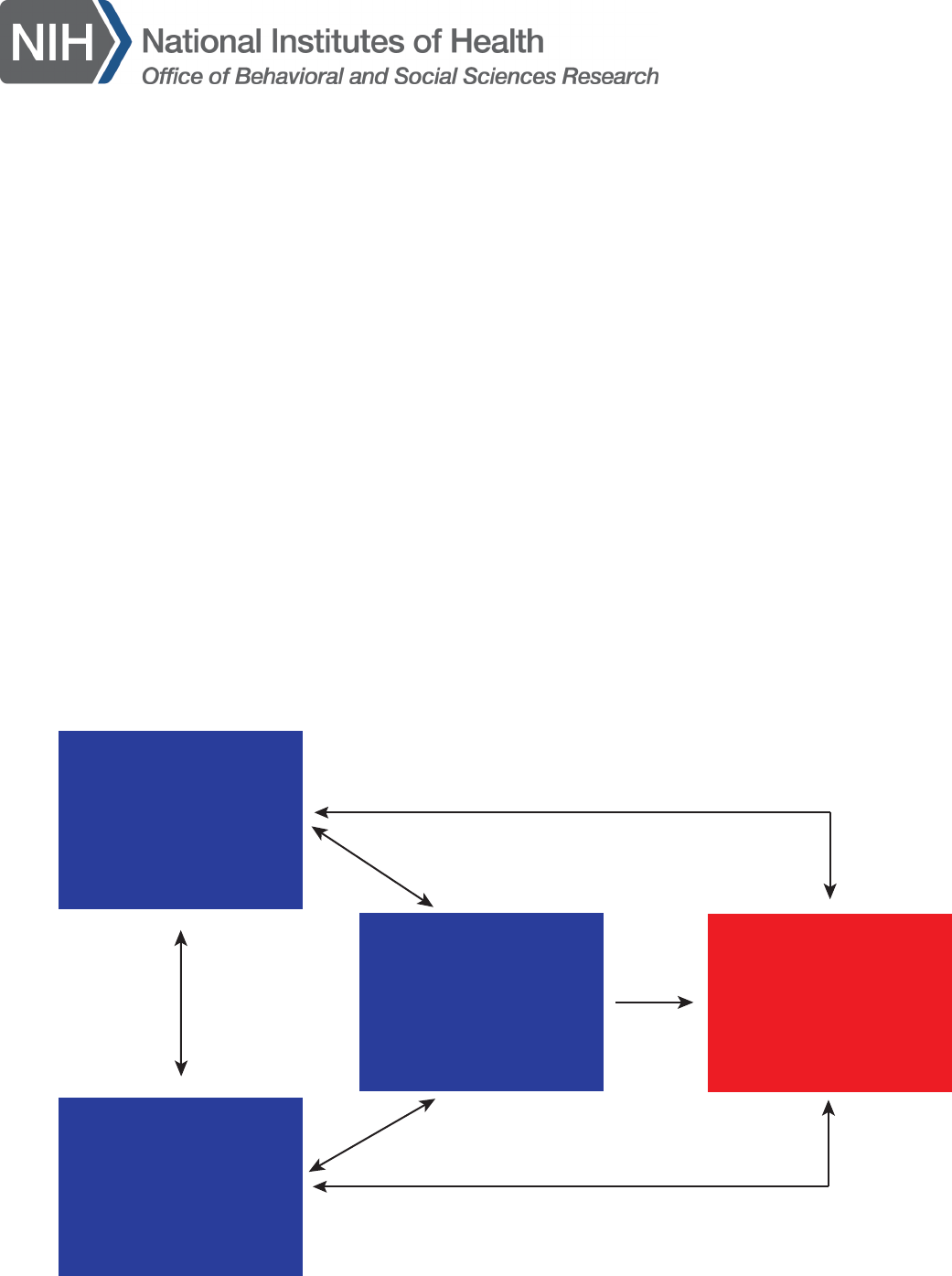

The guiding philosophy of OBSSR is that scientic advances in the understanding, treatment,

and prevention of disease will be accelerated by greater attention to behavioral and social factors

and their interaction with biomedical variables. Figure 1 illustrates the various factors that deter-

mine health outcomes, which involve behavioral/sociocultural/environmental, physiological, and

genetic factors, and the interactions among these categories. Although the contribution of each

category may vary from disease to disease, there is now ample evidence supporting this integrat-

ed perspective of causation for most health problems. For example, this conceptualization may

be applied to an array of disorders including heart disease, cancer, diabetes, AIDS, depression,

substance abuse, stroke, asthma, injuries, anxiety disorders, chronic pain, infant mortality, and

dental problems. Furthermore, the categories outlined in gure 1 represent not only risk factors

for disease, but identify targets for intervention. Although most of our treatment research efforts

have been aimed at the physiological category and associated drug interventions, research

clearly demonstrates the efficacy of behavioral and social interventions for a large number of dis-

orders. Therefore, a vision for the OBSSR is that through its work, this broader conceptualization

of health will be used to guide the scientic mission of the NIH.

behavioral,

sociocultural

and

environmental

factors

physiological

factors

health

outcomes

genetic

factors

Figure 1: Factors affecting health

Page 9

The Strategic Planning Process

In order to fulll this vision, OBSSR, during its rst year, initiated a strategic planning process.

The goal of the strategic planning process was to bring together the relevant scientic communi-

ties to assist OBSSR in charting its future direction and in establishing its priorities. Two strategic

planning meetings were held in February and March of 1996 involving over 70 scientists, science

administrators, and representatives of science organizations. These individuals worked to outline

the specic goals, strategies, and actions that are summarized in this strategic plan, which will

constitute the core activities for OBSSR over the next 3 to 5 years.

Overview of the Strategic Plan

As shown in gure 2, the ultimate objective for the NIH is to

improve health through the support of scientic research. To

achieve this objective, OBSSR will work to enhance the effec-

tiveness of the NIH through greater attention to behavioral and

social sciences research (gure 2). The OBSSR strategic plan is

organized around goals, strategies, and actions. Three goals were

improve health and

well being of people

enhance the

effectiveness of NIH

through greater attention

to behavioral and social

sciences research

identied for OBSSR and are shown in gure 3. These goals form

the core of the OBSSR strategic plan and are described on the

following pages.

Figure 2: The ultimate

objectives of the OBSSR

Page 10

improve health and

well being of people

enhance the

effectiveness of NIH

through greater attention

to behavioral and social

sciences research

enhance

behavioral and

social sciences research

and training

integrate a

biobehavioral

perspective

across NIH

improve

communications

among health

scientists and with

the public

Figure 2: The goals of the OBSSR

Goal 1

Enhance behavioral and social sciences research and training

A major part of the Congressional mandate for OBSSR was for it to work to increase support for

behavioral and social sciences research and training at NIH, both in the extramural and intramu-

ral programs. To accomplish this, OBSSR must assist NIH in identifying and capitalizing on the

numerous scientic opportunities that exist in the behavioral and social sciences. In addition to

biobehavioral research (see Goal 2 below), these opportunities exist in such areas as the iden-

tication of new risk factors; the development of new treatment and prevention approaches; and

research on basic behavioral and social processes relevant to health. The office must also work to

increase the pool of scientists who are trained to make discoveries in these areas for the ultimate

benet of the public.

Page 11

Goal 2

Integrate a biobehavioral, interdisciplinary perspective across NIH

Congress mandated that specic attention be devoted to integrating a biobehavioral perspec-

tive into research at NIH. Biobehavioral research, also known as biosocial and biopsychosocial

research, combines knowledge and approaches from biomedical, behavioral, and social science

disciplines to gain a better understanding of the complex, multifaceted interactions that deter-

mine healthy and pathological human functioning. As such, biobehavioral research represents

an exciting new frontier for the health sciences and for NIH. Examples of biobehavioral research

include such areas as behavioral cardiology, cognitive and behavioral neuroscience, psychoneuro-

immunology, and behavioral genetics.

Goal 3

Improve communication among health scientists and with the public

Improved communication among health scientists, and between scientists and the public, is

crucial to advancing behavioral and social sciences research and improving health. It was recom-

mended that OBSSR develop a comprehensive communications plan that would involve activities

aimed at 1) improving communication and information exchange among behavioral and social

scientists; 2) improving communication between sociobehavioral and biomedical scientists; 3)

increasing the dissemination of behavioral and social science ndings to the public and to health

care providers; 4) improving media coverage of behavioral and social sciences research; and 5)

ensuring that policymakers are kept abreast of developments in these elds.

Page 12

goal 1

strategy 1 strategy 2

action 1 action 2

action 3

Figure 4: The relationship between goals. strategies and actions

To achieve the three preceding goals, specic strategies and actions were recommended. Figure

4 shows the relationship between goals, strategies, and actions. The strategies represent answers

to the “what” question. That is, given the goals of OBSSR, what, in a broad sense, can the office

do to achieve them? Once broad strategies are outlined, specic actions must be delineated.

These actions represent answers to the “how’ question. That is, how do we best carry out these

strategies? Thus, actions describe the various activities that will address each strategy. In fact,

one short-term measure of the success of OBSSR, or what is often called a performance indica-

tor, is the number of recommended actions that were actually taken.

Page 13

Section Two: The OBSSR Strategic Plan

Section One: The OBSSR Strategic Plan

This section unites the OBSSR goals and strategies with specic actions. Each goal is connected

to several strategies and an even larger number of actions. The strategies and actions associat-

ed with each goal are provided below. In cases where particular actions address more than one

strategy or goal, cross-referencing is used.

Goal 1

Enhance behavioral and social sciences research and training Actions:

Strategy 1.1

1.1a Develop trans-NIH requests for applications and program announce-

ments.

Capitalize on sci-

entic opportunities

1.1b Explore partnerships between NIH institutes & centers and the private

in behavioral and

sector (e.g. managed care companies, foundations, etc.) for the funding of

social research

behavioral and social sciences research.

across NIH areas.

1.1c Use OBSSR funds to support peer-reviewed, highly rated, but

unfunded behavioral and social science proposals.

1.1d Supplement biomedical Center Grants to add behavioral and social

components (also relates to strategy 2.3).

1.1e Supplement behavioral and psychosocial treatment-related grants to

support the dissemination and implementation of ndings (also relates to

strategy 3.2).

1.1f Explore ways to expand small grant mechanisms for newer investiga-

tors.

1.1g Support conferences designed to increase interest of behavioral and

social scientists in relatively unexplored health

1.1h Provide assistance when warranted to ensure the appropriate review

of social and behavioral research grant proposals.

Page 14

Strategy 1.2

Enhance behavioral

and social research

in the NIH Intra-

mural Research

Program

Strategy 1.3

Increase training

opportunities in be-

havioral and social

sciences research

Actions

1.2a Meet with intramural research program science directors to discuss

inclusion of behavioral and social research.

1.2b Develop a postdoctoral training program for behavioral and social sci-

entists in the intramural research program (also relates to strategy 2.2).

1.2c Develop interagency personnel agreements for senior behavioral and

social scientists to work in the intramural research program (also relates to

strategies 2.2).

1.2d Send the OBSSR denition of behavioral and social sciences research

to all institute & center directors and to the NIH director explaining the

process of development of the denition and recommending that it be

adopted as the official NIH denition.

Actions

Develop postdoctoral training programs for behavioral and social scientists

in the NIH intramural research program (also relates to strategy 1.2).

Explore ways of expanding National Research Service Award support for

behavioral and social scientists.

Support short-term summer training workshops for interdisciplinary

research for social, behavioral, and biomedical scientists (also relates to

strategies 2.1 and 2.2).

Create social and behavioral science training programs for middle and high

school teachers (also relates to strategy 3.2).

Develop partnerships with foundations for funding of behavioral and social

science training.

Page 15

Strategy 1.4

Highlight the con-

tributions of be-

havioral and social

sciences research

to the improvement

of health

Strategy 1.5

Increase the visi-

bility of behavioral

and social sciences

within the NIH com-

munity

Actions

1.4a Commission literature reviews for biomedical journals on selected

topics related to behavioral and social science contributions to public health

and health science.

1.4b Develop and distribute fact sheets to relevant parties on behavioral

and social contributors to the etiology, prevention, and treatment of disease.

1.4c Develop and distribute fact sheets to relevant parties on reductions in

costs and health-care utilization resulting from behavioral and social inter-

ventions.

1.4d Identify institute & center scientic problems and provide solutions

based on behavioral and social sciences research.

1.4e Provide forums for behavioral treatment researchers to meet with

service providers (also relates to strategy 3.2).

1.4f Establish intergovernmental personnel agreements program for behav-

ioral and social science researchers to work in institute & center adminis-

trative offices.

Actions

1.5a Sponsor an ongoing scientic seminar series in conjunction with the

Behavioral and Social Sciences Research Coordinating Committee (BSSR-

CC).

1.5b Organize regular informal brieng sessions on behavioral and social

research for the NIH director and for institute & center directors.

Page 16

1.5c Facilitate behavioral and social sciences research interest groups

within the NIH community.

1.5d Organize regular conferences at NIH on cross-cutting behavioral and

social science topics.

1.5e Send the OBSSR denition of behavioral and social sciences research

to all institute & center directors and to the NIH director explaining the

process of development of the denition and recommending that it be

adopted as the official NIH denition.

Goal 2

Integrate a biobehavioral interdisciplinary perspective into all NIH research areas Actions

Strategy 2.1

Increase commu-

nication and coop-

eration between

sociobehavioral

and biomedical

researchers

2.1a Sponsor workshops, speakers, and symposia at NIH and at profes-

sional meetings on interdisciplinary research for behavioral and biomedical

investigators.

2.1b Commission literature reviews for biomedical publications that inte-

grate and highlight biobehavioral interactions (also relates to strategy 1.4).

2.1c Develop cross-disciplinary funding initiatives (also relates to strategy

2.3).

2.1d Create an internet-based discussion group for cross-disciplinary ex-

changes.

2.1e Establish a working group to promote cross-disciplinary research.

2.1f Convene a consensus conference on a common nomenclature for

“phases” of behavioral treatment research, analogous to that used for

clinical trials in medical studies, to facilitate communication and under-

standing across biomedical and behavioral treatment areas.

2.1g Establish intergovernmental personnel agreements program for extra-

mural behavioral and social scientists to work at NIH (also relates to strate-

gies 1.2 and 1. 4 ).

Page 17

Strategy 2.2

Increase

inter-disciplinary

training opportuni-

ties

Strategy 2.3

Create

inter-disciplinary

funding initiatives

Actions

2.2a. Support short-term training workshops for biomedical and behavioral

scientists to become familiar with each others’ methods and procedures

(also relates to strategy 1.3).

2.2b. Conduct behavioral and social science research methodology work-

shops at biomedical meetings (also relates to strategy 1.3).

2.2c. Develop post-doctoral fellowship program in the NIH intramural

research program (also relates to strategies 1.2, 1.3, 2.4).

2.2d. Enlist the assistance of the Institute of Medicine of the National

Academy of Sciences in examining training requirements for interdisciplin-

ary research (also relates to strategy 1.3).

Actions

2.3a. Supplement biomedical research centers with funds for interdisciplin-

ary pilot research (also relates to strategy 1.1).

2.3b. Develop trans-NIH requests for applications and program announce-

ments that require interdisciplinary collaborations (also relates to strategy

1. 1 ).

2.3c. Supplement biomedical requests for applications and program an-

nouncements to support biobehavioral research (also relates to strategy

1. 1 ).

Page 18

Strategy 2.4

(see strategy 1.5 for specic actions)

Increase the

visibility of behav-

ioral and social

sciences within the

NIH community

Goal 3

Improve communication among scientists and with the public Actions:

Strategy 3.2

Disseminate

behavioral and

social science

research ndings

to the public and to

practitioners

Actions

3.2a. Improve media coverage of behavioral research (also relates to

strategy 3.3).

3.2b. Create a website for lay audiences summarizing new ndings.

3.2c. Provide forums for clinical researchers to meet with service providers

(also relates to strategy 1.4).

3.2d. Assist in the development of clinical guidelines for the use of behav-

ioral treatment approaches.

3.2e. Develop funding initiatives on dissemination of behavioral and social

science research ndings (also relates to strategy 1.1).

3.2f. Hold periodic briengs for Congressional members and staffers on

important ndings in the behavioral and social sciences.

3.2g. Write Opinion/Editorial articles on ndings relevant to current issues

in public health (also relates to strategy 3.3).

3.2h. Work with health care providers and managed care companies to

incorporate scientically validated behavioral treatment approaches into

medical care.

Page 19

Strategy 3.3

Improve media

coverage

3.2i. Conduct lectures for patient advocacy groups.

3.2j. Create social and behavioral science training programs for middle and

high school teachers (also relates to strategy 1.3).

3.2k. Create programs that encourage researchers to guest lecture in local

community.

3.2l. Meet regularly with representatives from behavioral and social science

organizations and their boards of directors.

3.2m. Organize workshops on how behavioral and social scientists can

involve and get the support of local communities for research.

Actions

3.3a. Assess the current status of behavioral and social science research

coverage in the print media.

3.3b. Organize a series of seminars for medical and science writers on

important new ndings.

3.3c. Invite media representatives to visit active sociobehavioral laborato-

ries and eld sites.

3.3d. Provide information on new ndings in the behavioral and social

sciences to NIH public affairs and communications offices.

3.3e. Co-sponsor science writer fellowships in conjunction with science

organizations.

3.3f. Write Opinion/Editorial pieces on social and behavioral research

relevant to current public health issues (also relates to strategy 3.2).

3.3g. Develop and distribute one-page fact sheets to media representatives

on the relevance of behavioral and social factors to the etiology, prevention,

and treatment of disease (also relates to strategy 1.4).

Page 20

Section Three: Appendices

Appendix A:

OBSSR STRATEGIC PLANNING MEETING ORGANIZING COMMITTEE

Ronald Abeles, Ph.D.

Behavioral and Social Research Program

National Institute on Aging

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Edward Laumann, Ph.D.

Sociology Department

University of Chicago

Chicago, IL

Lucile Adams-Campbell, Ph.D.

Howard University Cancer Center

Washington, DC

Barbara Rimer, Ph.D.

Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center

Duke University School of Medicine

Durham, NC

Norman B. Anderson, Ph.D.

Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Susan Solomon, Ph.D.

Office of Behavioral

and Social Sciences Research

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Virginia Cain, Ph.D.

Office of Behavioral

and Social Sciences Research

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Marina L. Volkov, Ph.D.

Office of Behavioral

and Social Sciences Research

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Margaret Chesney, Ph.D.

Prevention Sciences Group

School of Medicine

University of California, San Francisco

San Francisco, CA

Ellen Stover, Ph.D.

Office on AIDS

National Institute of Mental Health

National Institutes of Health

Rockville, MD

James Jackson, Ph.D.

Institute for Social Research

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, MI

Consultants

John Bryson, Ph.D.

Minneapolis, MN

Charles Finn

Minneapolis, MN

Page 22

Appendix B:

PARTICIPANTS IN OBBSR STRATEGIC PLANNING MEETINGS

Ronald Abeles, Ph.D.

Behavioral and Social Research Program

National Institute on Aging

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Hortensia Amaro, Ph.D.

Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences

School of Public Health

University of Boston

Boston, MA

Norman B. Anderson, Ph.D.

Office of Behavioraland Social Sciences Research

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Judith Auerbach, Ph.D.

Office of AIDS Research

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Frank Baker

American Cancer Society

Atlanta, GA

Wendy Baldwin, Ph.D.

Office for Extramural Research

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Gordon Bower, Ph.D.

Condence Training, Inc.

Stanford, CA

Kelly Brownell, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

Yale University

New Haven, CT

Virginia Cain, Ph.D.

Office of Behavioral

and Social Sciences Research

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Patricia Carpenter, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

Carnegie Mellon University

Pittsburgh, PA

Margaret Chesney, Ph.D.

Prevention Sciences Group

School of Medicine

University of California, San Francisco

San Francisco, CA

Rodney R. Cocking, Ph.D.

National Research Council

Washington, DC

R. Lorraine Collins, Ph.D.

Research Institute on Addictions

Buffalo, NY

Rena Convissor, M.P.H.

Center for the Advancement of Health

Washington, DC

Paul Costa, Ph.D.

Laboratory of Personality and Cognition

National Institute on Aging

National Institutes of Health

Baltimore, MD

Cynthia Costallo, Ph.D.

American Sociological Association

Washington, DC

Page 23

Joel Dimsdale, M.D.

Department of Psychiatry

University of Southern California

La Jolla, CA

Glen Elder, Ph.D.

Carolina Population Center

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, NC

John A. Fairbank, Ph.D.

Research Triangle Institute

Research Triangle Park, NC

Representing International Society for

Traumatic Stress Studies

Geraldine Felton, Ed.D., R.N., F.A.A.N.

College of Nursing

University of Iowa

Iowa City, IA

Richard Fuller, M.D.

Division of Clinical

and Prevention Research

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse

and Alcoholism

National Institutes of Health

Rockville, MD

Thomas Glynn, Ph.D.

Division of Cancer Prevention

and Control

National Cancer Institute

National Institutes of Health

Rockville, MD

Ellen Gritz, Ph.D.

Department of Behavioral Sciences

M.D. Anderson Cancer Center

Houston, TX

Linda Harootyan

Gerontological Society of America

Washington, DC

Christine R. Hartel, Ph.D.

American Psychological Association

Washington, DC

Ed Hatcher

American Sociological Association

Washington, DC

Laura Hayman, Ph.D., R.N.

School of Nursing and Medicine

University of Pennsylvania

Wyndmoor, PA

Representing the American Heart Association

Loretta Sweet Jemmott, Ph.D., R.N.

School of Nursing

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, PA

David Johnson, Ph.D.

Federation of Behavioral, Psychological

and Cognitive Sciences

Washington, DC

Ernest Johnson, Ph.D.

Department of Family Medicine

Morehouse School of Medicine

Atlanta, GA

Joyce Justus, Ph.D.

Office of Science and Technology Policy

The White House

Washington, DC

Peter Kaufmann, Ph.D.

Division of Epidemiology

and Clinical Applications

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

National Institutes of Health

Rockville, MD

Page 24

Patricia C. Kobor

American Psychological Association

Washington, DC

Norman Krasnegor, Ph.D.

Center for Research

on Mothers and Children

National Institute of Child Health

and Human Development

National Institutes of Health

Rockville, MD

Alan Kraut, Ph.D.

American Psychological Society

Washington, DC

John Lanigan, Jr., Ph.D.

Institute for the Advancement

of Social Work Research

Washington, DC

Edward Laumann, Ph.D.

Sociology Department

University of Chicago

Chicago, IL

Eleanor Maccoby, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

Stanford University

Stanford, CA

George Maddox, Ph.D.

Center for Study of Aging

and Human Development

Duke University Medical Center

Durham, NC

Karen Matthews, Ph.D.

Department of Psychiatry

University of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh, PA

Sandra J. McElhaney, M.A.

National Mental Health Association

Alexandria, VA

John McKinlay, Ph.D.

New England Research Institute

Watertown, MA

Kristin Moore, Ph.D.

Child Trends

Washington, DC

Representing the Population Association

of America

Judith Ockene, Ph.D.

Division of Preventive

and Behavioral Medicine

University of Massachusetts

Medical School

Worcester, MA

Mary Margaret Overbey, Ph.D.

American Anthropological Association

Arlington, VA

Mary Ellen Oliveri, Ph.D.

Division of Neuroscience

and Behavioral Science

National Institute of Mental Health

National Institutes of Health

Rockville, MD

C. Tracy Orleans, Ph.D.

Research and Evaluation Division

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Princeton, NJ

Susan Persons

Society for Research

on Child Development

Washington, DC

Thomas Pickering, M.D., Ph.D.

Cornell Medical Center

New York, NY

Representing the Academy of Behavioral

Medicine Research

Page 25

Harold Pincus, M.D.

American Psychiatric Association

Washington, DC

Stephen W. Porges, Ph.D.

University of Maryland

College Park, MD

Representing the Society for

Psychophysiological Research

Enola Proctor, Ph.D.

George Warren Brown School

of Social Work

Washington University

St. Louis, MO

Gary Sandefur, Ph.D.

Department of Sociology

University of Wisconsin - Madison

Madison, WI

Julia R. Scott, R.N.

National Black Womens’ Health Project

Washington, DC

Angela L. Sharpe

Consortium of Social Science Associations

Washington, DC

Paula Skedsvold, Ph.D.

Society for the Psychological

Study of Social Issues

Washington, DC

James Smith, Ph.D.

Rand Corporation

Santa Monica, CA

Susan Solomon, Ph.D.

Office of Behavioral

and Social Sciences Research

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Linda Spear, Ph.D.

Department of Psychology

State University of New York, Binghamton

Binghamton, NY

Gerald Sroufe

American Educational Research Association

Washington, DC

Sarah Evans Stevens

Federation of Behavioral, Psychological

and Cognitive Sciences

Washington, DC

Ellen Stover, Ph.D.

Office on AIDS

National Institute of Mental Health

National Institutes of Health

Rockville, MD

Tony Strickland, Ph.D.

Biobehavioral Research Center

Charles R. Drew University

of Medicine and Science

Los Angeles, CA

Stephen Suomi, Ph.D.

Laboratory of Comparative Ethology

National Institute of Child Health

and Human Development

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Jennifer Sutton

Association of American Medical Colleges

Washington, DC

Jose Szapocznik, Ph.D.

Department of Psychiatry

and Behavioral Sciences

University of Miami School of Medicine

Miami, FL

Robert Trotter, Ph.D.

Page 26

Department of Anthropology

Northern Arizona University

Flagstaff, AZ

Jaylan Turkkan, Ph.D.

Division of Basic Research

National Institute on Drug Abuse

National Institutes of Health

Rockville, MD

Donald Vereen, Ph.D.

Office of the Director

National Institute on Drug Abuse

National Institutes of Health

Rockville, MD

Marina L. Volkov, Ph.D.

Office of Behavioral

and Social Sciences Research

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, MD

Linda Waite, Ph.D.

Department of Sociology

University of Chicago

Chicago, IL

Stephen Weiss, Ph.D., M.P.H.

Department of Psychiatry

and Behavioral Sciences

University of Miami School of Medicine

Miami, FL

redford Williams, M.D.

Department of Psychiatry

Duke University Medical School

Durham, NC

Judith Costine Woodward

Society of Behavioral Medicine

Rockville, MD

Page 27

Publication Number 97-4237

Publication Title Strategic Plan for the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research at NIH

Year Published 1997

IC Office of The Director

Page 28