Eliminating the worst forms of child labour

A report of the ILO Caribbean tripartite meeting on the worst forms of child

labour, Kingston, Jamaica - 6-7 December, 1999

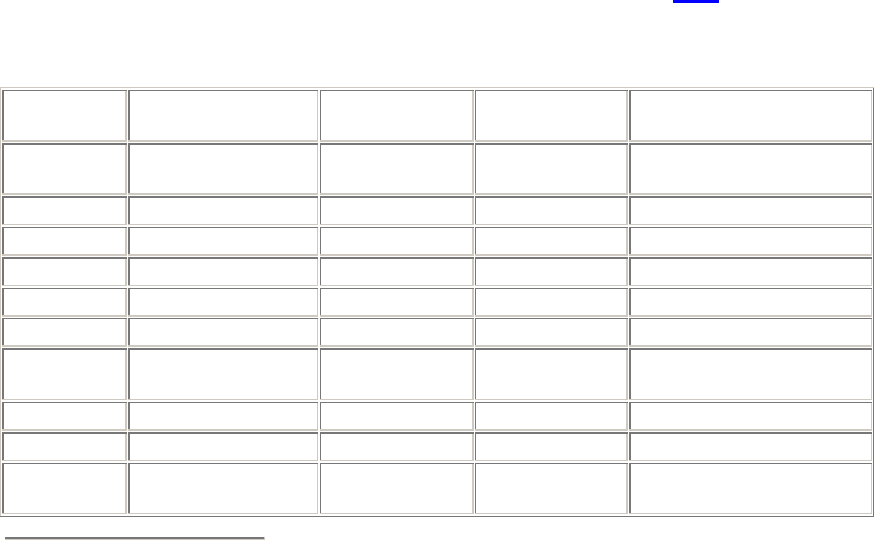

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface

Part one: The problem of child labour - Overview

Part two: Introduction to the Meeting and opening ceremony

Part three: International perspective

International labour standards and the new ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour

Convention, 1999 (No. 182)

The new Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labour - Challenges for the

Caribbean

Group work - Ratification and implementation of Convention No. 182

The ILO International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC)

Part four: Regional and national trends and experience

UNICEF: The socio-economic experience of children in the Caribbean

Working with street children in Jamaica: The experience of Children First

Child labour in the Caribbean: Country profiles

Group work - National programmes of action

Part five: Conclusions of the Meeting

Annex 1: Introductory remarks by Willi Momm, Director, ILO Caribbean Office

Annex 2: Background paper of the Meeting: Child labour in an international perspective

by Michele Jankanish, Senior Specialist, International Labour Standards and Labour Law

Annex 3: Ratification of Child Labour Conventions in the Caribbean

Annex 4: Compulsory education and minimum ages for admission to employment in

selected Caribbean countries

Annex 5:

Programme of the Meeting

Annex 6:

List of participants

Preface

With the adoption in June 1999 of the ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention,

No. 182, eliminating the worst forms of child labour has been set as the priority of

national and international action toward the total abolition of child labour.

Child labour and the worst forms of exploitation exist everywhere. The Caribbean is no

exception. While the true nature and extent of the problem might not yet be known,

efforts must be made to prevent new children from suffering and to find and help those

that are. Pressures on the economies, the social fabric of the region and a growing tourist

trade can lead to increased risk of child labour. Without a renewed commitment to quality

education, many children and their families may succumb to other temptations and

exploitation.

To address these concerns and make Convention No. 182 known in the region, the ILO

organized the ILO Caribbean Tripartite Meeting on the Worst Forms of Child Labour in

Kingston, Jamaica, from 6 to 7 December, 1999. This publication contains the

proceedings and conclusions of that Meeting.

The real work now begins to follow-up those conclusions. It is hoped that governments in

the region will move quickly towards ratification of Convention No. 182 and effective

implementation in practice. We trust that this publication will provide guidance in this

process.

Willi Momm

Director

ILO Caribbean Office

Frans Röselaers

Director

InFocus Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour

Part one: The problem of child labour - Overview (1)

The ILO estimates that in developing countries alone, about 250 million children between

the ages of five and 14 years work in economic activity and at least 120 million of these

children work full-time. Africa has the highest incidence of child labour with

approximately 41 per cent of children between the ages of five and 14 working,

compared to 22 per cent in Asia and 17 per cent in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Latin America and the Caribbean account for about 7 per cent of the global figure. More

boys than girls work. Surveys, however, do not take into account domestic work in one's

own household or caring for sick or disabled family members. More girls than boys

perform this type of work. If such work were taken into account, there would be little or

no variation among the sexes in the total number of working children, and the number of

working girls might exceed that of boys.

Of the 250 million working children, approximately 50 to 60 million between the ages of

five and 11 are working in circumstances that could be termed hazardous considering

their ages and vulnerability. In some cases nearly 70 per cent of working children are

engaged in hazardous work. From five per cent to more than 20 per cent of working

children suffer actual injuries or illnesses; some have to stop working permanently.

Recent surveys at the national level have demonstrated that a very high proportion of

working children are physically injured or fall ill while working.(2)

In many countries, including in the sub-region, data on working children either do not

exist or are incomplete, since traditional survey methodologies often do not cover the

hidden activities of school age children. The ILO has developed and tested

comprehensive child labour surveys, special modules, and in collaboration with UNICEF,

rapid assessment techniques to address the deficiencies in information on the true nature

and extent of child labour.

Hazards children face at work

Children toil for long hours in fields, factories and private homes, in small workshops and

garages, in mines and quarries, and in situations that are dangerous or hazardous to their

health and development. They are also bought and sold, forced to work in conditions of

slavery and engaged in prostitution, pornography and other illicit activities.

Child labour on average is twice as high in rural as in urban areas. It is estimated that 70

per cent of all working children are engaged in agriculture. Occupational health and

safety experts consider agriculture to be among the most dangerous of occupations.

Climatic exposure, work that is too heavy for young bodies and accidents such as cuts

from sharpened tools are some of the hazards children face. Modern agricultural methods

bring further hazards in their wake, use of toxic chemicals and motorized equipment,

usually without the benefit of training or safety precautions. While generally found only

in larger agricultural enterprises, small family farms also increasingly make use of such

methods. The hazards associated with agriculture are numerous, and this is reflected in

the number of injuries and illnesses recorded for children working in this sector. In many

countries the hazards and risks to health are compounded by poor access to health

facilities and education, poor housing and sanitation, and inadequate diets of rural

workers.

Children in domestic service are among the most vulnerable and exploited of all. These

children are the most difficult to protect as they are largely invisible, hidden and ignored.

Most come from extremely poor or single-parent families, or have been abandoned or

orphaned. Improved statistical survey methods pioneered by the ILO indicate that the

practice is widespread. In Indonesia, for example, an estimated 5 million children are in

domestic service, and 20 per cent of all Brazilian, Colombian, and Ecuadorean girls

between the ages of ten and 14 work as domestics. In rural areas the percentages rise, for

example, in Brazil 36 per cent of girls between the ages of ten and 14 work as domestics;

in Colombia, it is 32 per cent; and in Ecuador, as many as 44 per cent of girls of this age

group work as domestics. (3)

Another abhorrent situation is the use of children in illicit activities such as the sale and

trafficking of drugs. Children can be engaged in the process at different levels, from

smuggling drugs across borders to selling drugs on the street. Children are often exposed

to violence and are given weapons to use, such as firearms. Some children are lured into

the drug trade by getting them to use drugs and then maintaining their participation by

paying them with drugs. Other children may be induced to sell drugs for the financial

gains it promises.

The commercial sexual exploitation of children is one of the most brutal forms of

violence against them. Even more worrying is that there are indications that the problem

is on the rise. Child victims suffer physical, psychological and emotional abuse. They are

exposed to sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV/AIDS. They are often introduced to

drugs to control them, further endangering their lives and making recovery difficult.

Younger and younger children are being sought in the belief that they will be free of

HIV/AIDS, yet it is they who are most likely to be infected since younger persons have

greater biological vulnerability to sexually transmitted diseases. Both girls and boys are

subject to exploitation in prostitution and pornography. Sex tourism has led to an increase

in the number of boy victims.

The effects of hazardous work and conditions on children can be devastating, causing

irreversible damage to their psychological, physical and physiological development. The

impact of physically strenuous work such as carrying heavy loads or being forced to

adopt unnatural positions at work can permanently distort or disable growing bodies.

There is evidence that children suffer more readily from chemical hazards and radiation

than adults, and that they have less resistance to diseases. Children are also much more

vulnerable than adults to physical, sexual and emotional abuse, and suffer more

devastating psychological damage from living and working in an environment in which

they are denigrated or oppressed. Thus, the assessment of the dangers of child labour go

beyond the relatively limited concept of work hazard as applied to adults and includes the

developmental aspects of childhood.

Child labour in the Caribbean

The reports prepared by the participants to the ILO Caribbean Tripartite Meeting on the

Worst Forms of Child Labour and the discussions during the Meeting indicate that an

unknown number of children are working in the sub-region, sometimes in violation of

national law and international standards. Children in the Caribbean are reported to be

working in agriculture, selling on the street, involved in the drug trade, and in domestic

work. They are also exploited in prostitution and pornography. There is a lack of data,

however, on the numbers involved, or how many can be considered to be involved in

activities that would fall under the ILO's new Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention.

The potential threats from a growing tourism industry are sometimes ignored or

misunderstood and certain forms of entertainment, such as go go clubs, employ and

exploit girls. There is a sense in some countries that the problem is small or does not

exist. An increased awareness to what might be going on, what can happen and keen

attention to prevention is thus necessary.

The participants in the Meeting concluded that in addition to quick ratification of

Convention No. 182, efforts at awareness raising and data collection were needed, as well

as strong government leadership and the commitment from the social partners and civil

society to determine the extent and nature of the problem and to join action against child

labour in the region.

ILO action against child labour

ILO activities include adopting international standards and supervising their

implementation, carrying out research and analysis, disseminating information, creating

public awareness, mobilizing a worldwide movement against child labour, assisting

countries in the development of policy and law and carrying out direct action to remove

children from hazardous situations and rehabilitate them. The ILO also assists and

strengthens the ability of employers' and workers' organizations to become involved, as

well as other parts of civil society.

International standards provide the broad framework for national legal and practical

action. The most comprehensive standards are the Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (No.

183) and its accompanying Recommendation, No. 146. Given the persistence of child

labour in the world and the serious hazards and violation of human rights associated with

much of it, the International Labour Conference adopted the Worst Forms of Child

Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182) and Recommendation No. 190, to complement the

earlier standards and set elimination of the worst forms as priority for national and

international action.

National policy development and practical action is assisted by the ILO through its

International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC).

The International Programme on the Elimination of

Child Labour (IPEC)

The ILO's International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (5) is the world's

largest technical cooperation programme on child labour. It works by strengthening

national capacities to address the problem of child labour and by creating a worldwide

movement to combat it. Support is given to partner organizations to develop and

implement measures which aim at preventing child labour, removing children from

hazardous work, providing for their rehabilitation and social reintegration, and providing

alternatives for them and their families.

Member States express their political will and commitment to address child labour by

signing a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with IPEC. Steering committees are set

up at the national level to develop policies and programmes to be carried out in

cooperation with employers' and workers' organizations, NGOs and other concerned

groups in society. Action in preparation for full participation in IPEC is also carried out

in a large number of countries.

To address the need for sound information for the development of policies and

programmes and their effective monitoring, the ILO has set up the Statistical Information

and Monitoring Programme on Child Labour (SIMPOC). The intent is not only to refine

methodologies for conducting child labour surveys, but also to maintain data banks of

institutions, projects, legislation and other information necessary for evaluating and

designing effective policies and programmes to combat child labour. In the aftermath of a

recent training workshop on child labour survey methodologies (6) , several countries in

the Caribbean will participate with SIMPOC in improving their data collection on child

labour.

Future action

Much has been achieved in the past few years in raising the awareness of world public

opinion, governments and powerful interest groups to the scourge of child labour, and in

deepening understanding of its causes and consequences. It is now increasingly

recognized that the fight against child labour is inevitable and irreversible. The children

of the Global March against Child Labour (7)

d propelled a global movement expressing

great hopes and expectations for a better future for children around the world. The

challenge now is to ensure that these hopes and expectations are not disappointed and that

a brighter future awaits the world's children.

The participants at the ILO Caribbean Tripartite Meeting on the Worst Forms of Child

Labour committed themselves upon return to their countries to seek early ratification of

Convention No. 182. The conclusions of that Meeting were also presented to the Third

Meeting of the Council for Human and Social Development (COHSOD) of CARICOM.

The Council urged member States to ratify all ILO core Conventions including

Convention No. 182.

ILO support is also planned for activities in Belize, Guyana, Jamaica and Suriname. The

social partners are also being encouraged to undertake awareness raising and promotional

campaigns. The ILO has made ratification and effective implementation of the Worst

Forms of Child Labour Convention, No. 182, a priority. The ILO Director-General, Mr.

Juan Somavia has said,

"With this Convention, we now have the power to make the urgent eradication of

the worst forms of child labour a new global cause. This cause must be expressed,

not in words, but deeds, not in speeches, but in policy and law".

(1) For more information and references see ILO: Child labour: Targeting the intolerable, Report VI (1), International Labour Conference,

86th Session, 1998 (Geneva, 1996); N. Haspels and M. Jankanish (eds.): Action against child labour (Geneva, ILO, 2000); and the ILO

website: www.ilo.org/childlabour

(2) K. Ashagrie: Statistics on working children and hazardous child labour in brief (Geneva, ILO, revised 1998), p. 10.

(3) ILO: Child Labour: Targeting the intolerable, op.cit., pp. 14-15.

(4) See Annex 2 for more details: Child labour in an international perspective: The new ILO Convention on the elimination of the worst forms

of child labour.

(5) Visit the ILO's website: www.ilo.org/childlabour. Current programming activities in the ILO will bring together all ILO activities on child

labour under an InFocus Programme on child labour, retaining the designation of IPEC.

(6) ILO: Report on ILO Sub-regional Training Workshop for Statisticians on Child Labour Statistics and Survey Methodologies, Port of Spain

1999.

(7) The Global March began in 1997 as a broad alliance of civil society, including non-governmental organizations, workers' organizations and

child rights and human rights groups. Members of the March travelled through Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America and North America

demonstrating against child labour, for education and for the new Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labour. Representatives of the

March addressed the delegates to both the 1998 and 1999 International Labour Conference.

Part two: Introduction to the Meeting and opening ceremony

The ILO Caribbean Office and the International Programme on the Elimination of Child

Labour of the ILO organized the Caribbean Tripartite Meeting on the Worst Forms of

Child Labour in collaboration with the Jamaican Ministry of Labour, Social Security and

Sport. The Meeting was held from December 6 to 7, 1999 in Kingston, Jamaica.

Objectives of the meeting

• inform representatives of government, workers' and employers' organizations about the

provisions of the new ILO Convention concerning the prohibition and immediate action

for the elimination of the worst forms of child labour (No. 182) and their respective roles

under the new Convention

• provide for an exchange of views about the problem of child labour

• determine the necessary action to ensure rapid ratification of Convention No. 182

• begin a sub-regional assessment of what is known about child labour, national

legislative frameworks and policy initiatives

Participants

Tripartite delegations were invited from Antigua & Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Grenada,

Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago.

The Secretariat of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), the United Nations Children's

Fund (UNICEF) and the British Department for International Development (DFID) sent

observers. A list of participants is provided in Annex 6.

Opening ceremony

Mr. Anthony Irons, Permanent Secretary in the Jamaican Ministry of Labour, Social

Security and Sport, welcomed delegates and chaired the opening session.

Mr. Willi Momm, Director of the ILO Caribbean Office placed the meeting in the context

of the ongoing negotiations at the World Trade Organization and the debate about linking

trade and labour standards. The full text of the speech is reproduced in Annex 1.

Senator Leroy Trotman, representing the Caribbean Congress of Labour (CCL)

congratulated the Minister, The Honorable Portia Simpson-Miller, for having spoken out

in ILO fora and for trying to develop a common Caribbean position on child labour

matters. Equally, he commended the ILO for recognizing that the Caribbean needed to

protect its moral and social fabric by preventing the problem of child labour from

becoming out of hand. If prevention were to be effective, however, states needed to

guarantee the right to education and equality of opportunity regardless of colour, gender

or sexual orientation. Further, he pointed to the need to enhance the political leverage of

the ministries of labour in the region.

Mr. Walton Hilton Clarke, Vice-President of the Caribbean Employers' Confederation

(CEC), thanked Senator Trotman, who served as the Workers' Vice-Chairperson on the

International Labour Conferences' Committee on Child Labour, for his contribution to the

successful adoption of the ILO Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labour. He

noted the importance of the Meeting and the need for the Caribbean to look inward in

order to move from plans into measurable results. None of the employers should be

content as long as some persons were employing or exploiting children in any of the

worst forms of child labour. It was crucial to disseminate the findings of the Meeting, as

child labour was often highly secretive and presented a great challenge to regional actors

to move from words to action.

Mr. Frans Röselaers, Director of the ILO's International Programme on the Elimination

of Child Labour (IPEC), stated that child labour was the principal cause of exploitation

and abuse of children. Child labour robbed children of their health, education and even

their lives. It had many faces. For example, children were found digging in mines, sold

into bonded labour and toiling long hours as domestic workers. Mr. Röselaers drew

attention to the children in the Caribbean who spent their days wiping windshields to earn

money or doing back-breaking agricultural work and to those who were working in more

hidden situations, such as in domestic service. These hidden forms of work were done

most often by girls.

In view of these facts, global concern and consensus on the need to do something against

child labour was growing. He referred to the Global March Against Child Labour and the

unanimous adoption in 1999 of the new ILO Convention on the Worst Forms of Child

Labour. In addition to the specific ILO Conventions on child labour, the Declaration on

Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work provided a further and much broader

framework for the elimination of child labour.

Mr. Röselaers focussed attention on the following goals for the Meeting:

• to discuss the process of ratification of Convention No. 182, the possible obstacles to

ratification and assistance needed to facilitate ratification, as well as implementation

• to learn about the characteristics of the child labour problem in the Caribbean and to

explore follow-up collaboration on a national basis

• to consider the setting up of a sub-regional education programme jointly with other UN

organizations, such as UNICEF and UNESCO to focus on preventing child labour

Ms. Majorie Taylor, Ambassador and Special Envoy for Children in the Jamaican

Ministry of Health, commended the ILO on the opportune time for hosting the Meeting

as the issue of child rights was only just becoming accepted in Jamaican society.

Formerly, the welfare of children was largely left to the discretion of parents who, at

times, saw nothing wrong, for example, in taking children out of school on Fridays, when

their help was needed. The problem of prostitution was only now coming to the forefront.

Ms. Taylor noted the outdated nature of Jamaica's Juvenile Act which allowed children to

work as early as 12 years of age. She also welcomed the draft legislation on child

protection that was currently being debated. Against the background of growing national

awareness, the restructuring of the Government's children's services and intensified

cooperation with international agencies, she saw this as a good basis for early ratification

of the new ILO Convention.

In her keynote address, the Honorable Portia Simpson-Miller, Minister of Labour, Social

Security and Sport welcomed all participants and commended the organizers of the

Meeting on their foresight. She stressed that the decision to focus on the worst forms of

child labour sent a clear message to protect the welfare of society's most vulnerable

members and to take the necessary action urgently.

Minister Simpson-Miller pointed out that the Caribbean challenge was special since little

was known about the full extent of these worst forms of child labour in Caribbean

societies. She acknowledged that such forms of child labour were usually `hidden' and

that poverty was one of the main contributing factors. She argued that the growing

numbers of street children were potential victims of these forms of exploitation and that

there was a need for greater social consciousness of the problem. Accordingly, a much

better and more coordinated policy response was needed, together with comprehensive

legal reform in order to put an end to conflicting signals about statutory age or conditions

under which children may work.

To meet this challenge, Minister Simpson-Miller called for a massive investment

initiative so that public budgets, corporate sponsorship and international support could be

enlarged. An attack on poverty was required to help build skills, change attitudes and

create the necessary framework for improving educational strategies. She stressed her

high expectations and the need for new commitments as well as revamped strategies that

would lead towards an effective social contract for the protection of children.

Mr. James Williams, Permanent Secretary at the Ministry of Education, Labour and

Social Security, in Saint Kitts and Nevis, gave the vote of thanks.

Part three: International perspective

International labour standards and the new ILO Worst Forms of Child Labour

Convention (No. 182)

Mr. Geir Myrstad, Senior Programme Officer at IPEC, chaired the first session on

international standards on child labour.

Ms. Michele Jankanish, Senior Specialist on International Labour Standards and Labour

Law in the ILO Caribbean Office, placed the new Worst Forms of Child Labour

Convention, 1999 in the context of the broader problem of child labour and existing

international standards (see Annex 2). One of the most important tools available to the

ILO for improving the legislation and practice of its member States in the fight against

child labour was the adoption and supervision of international labour Conventions and

Recommendations.

The ILO adopted its first Convention on child labour in the year of its formation, 1919,

the Minimum Age (Industry) Convention, (No. 5). Subsequently, a number of sectoral

Conventions on the minimum age of admission to employment were adopted. In 1973,

the ILO consolidated the principles in the Minimum Age Convention, (No. 138) and its

accompanying Recommendation No. 146. These applied to all sectors of economic

activity, whether or not the children were employed for wages. The Convention contained

flexibility provisions which acknowledged different levels of development and a

progressive approach toward the total elimination of child labour.

The new Convention did not revise or replace Convention No. 138, but complemented it.

While Convention No. 138 set standards of minimum age for admission to employment

or work, the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 focussed on the need for

immediate action to prohibit and eliminate the worst forms of child labour. The basic

obligation of ratifying States was to take immediate and effective measures to prohibit

and eliminate the worst forms of child labour as a matter of urgency for all those under

18 years of age. Urgency of action was emphasized as the forms of child labour covered

by the Convention were those that could not be tolerated in any country, regardless of the

level of development.

The "worst forms of child labour" comprise:

(a) all forms of slavery or practices similar to slavery, such as the sale and trafficking of

children, debt bondage and serfdom and forced or compulsory labour, including forced or

compulsory recruitment of children for use in armed conflict

(b) the use, procurement or offering of a child for prostitution, production of pornography

or pornographic performances

(c) the use, procurement or offering of a child for illicit activities, in particular for the

production and trafficking of drugs

(d) work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it was carried out, is likely to

harm the health, safety or morals of children

The Convention set out the process for determining which work was likely to harm the

health, safety or morals of children and directed that consideration be given to those

hazards spelled out in the Recommendation. The Convention also obliged ratifying States

to ensure the effective implementation and enforcement of the Convention, including the

provision and application of sanctions, penal or otherwise. The orientation to preventive

and practical action was illustrated by Article 7, Paragraph 2, which required States,

taking into account the importance of education in eliminating child labour, to take

effective and time-bound measures to:

(a) prevent the engagement of children in the worst forms of child labour

(b) provide the necessary and appropriate direct assistance for the removal of children

from the worst forms of child labour and for their rehabilitation and social integration

(c) ensure access to free basic education, and wherever possible and appropriate,

vocational training, for all children removed from the worst forms of child labour

(d) identify and reach out to children at special risk and

(e) take account of the special situation of girls

Preventing children from falling into the worst forms of child labour was key. At the

same time, removal of those children already found in the worst forms was urgent and

was to be accompanied by attention to their need for rehabilitation. Because of the

particular vulnerability of girls and their often hidden work situations, the new standards

made specific mention of the need to take account of their situation in designing

preventive, removal and rehabilitative measures. Outreach to other children at special risk

was also provided for.

The Convention also required the development or designation of monitoring mechanisms

to be decided upon after consultation with workers' and employers' organizations. To

further ensure effective action, countries were to design and implement programmes of

action to eliminate the worst forms of child labour as a priority. The Recommendation

provided that such programmes should aim at prevention, removal, rehabilitation and

social integration, through measures to address the educational, physical and

psychological needs of children. Furthermore, attention should be given to younger

children, the girl child, hidden work situations and children with special vulnerabilities or

needs. Communities where children were at special risk should be particularly targeted.

In addition, society in general should be mobilized through raising awareness.

Finally, the Convention called for member States to cooperate and assist each other. This

reinforced the sentiment that all countries were concerned with children trapped in the

worst forms of child labour no matter where they might be. In addition, while urgent

action was required, there was also the commitment to finding longer-term solutions to

the poverty and lack of educational opportunities that led children into intolerable work

situations. The donor community was invited to play a critical role in assisting countries

with eliminating the worst forms of child labour.

Recommendation No. 190 elaborated further on the hazards which would constitute the

worst forms of child labour; the type of data to be collected; effective enforcement

measures and the need to cooperate with international efforts to control the cross-border

aspects of the worst forms of child labour; ways to address the legal, social and economic

needs of the affected children and their families; and awareness raising, mobilization and

training activities.

The new Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labour - Challenges for the

Caribbean

Mr. Leroy Trotman, President of the ICFTU and Member of the Governing Body of the

ILO, focussed on challenges for the Caribbean and the significance of addressing child

labour, in particular its worst forms. The requirements for education and training had

dramatically changed over time - people could no longer be seen merely as tools. He

warned against the societal dangers of maintaining certain traditions and cultures that

nurtured privilege or class.

Mr. Trotman pointed to the complex sources of child labour: poverty, "vulgar

capitalism", suspended human values as well as human greed and perversity. He

welcomed the provisions of the new ILO Convention on the Worst Forms of Child

Labour, which drew an important line against unacceptable exploitation. However, he

stressed the difficulty of making Caribbean people accept that the region did indeed have

a problem. In order to protect and develop the region's human resources, children needed

to benefit from improved education. Efforts should also focus on an awareness raising

campaign which would anticipate problems and seek to prevent deteriorating economic

and social conditions.

Further, countries of the Caribbean needed to step up their political will so that they could

ratify the relevant Conventions and put in place necessary legislative reforms. The region

should be made aware of the important provisions of the Convention and should receive

necessary incentives to develop its human resources. As a result of the Meeting, he would

welcome the beginning of pilot activities in Jamaica as well as in other Caribbean

countries. However, he again emphasized that the entire educational system ought to be

upgraded and provided with a new regulatory mechanism which would no longer make

distinctions on the basis of social class.

In the discussion a number of questions were raised concerning assistance to poor

working children and the consequence of removing them from work. The ILO

representatives responded by emphasizing the principle of "nobody loses" which was

based on rehabilitation, education and a secure family income. Based on ILO experience

in removing children from child labour and providing for their educational needs, for

example, an environment had to be created to build the self-confidence of the children

before they could return to formal education. The rehabilitative process might be

supported through non-formal programmes before children were put back into the

mainstream of the regular school system. Depending on the age and situation of the child,

various education or training alternatives might be appropriate. Efforts were also made to

replace lost income. Ideally, an unemployed family member could take up the former

work of the child, but if this was not possible, direct or indirect support for schooling

could be considered. There were many approaches and considerations to be given to

possible action, but the goal was always to make the child better off through

interventions. In some cases not involving the worst forms of child labour, transition

measures could be provided, such as improved conditions of work.

The role and involvement of NGOs and other members of civil society were also

discussed. The Convention gave priority to consultations with workers' and employers'

organizations, while the views of other concerned groups were to be considered in

national programmes of action. The necessity for greater dialogue with civil society was

strongly underlined by the participants and the important role of NGOs recognized. This

was coupled, however, with concerns expressed by workers' organizations about the

representativeness of some non-governmental institutions in civil society and that some

were not dedicated to the principles of the ILO.

Group work - Ratification and implementation of Convention No. 182

The first session of group work was conducted with groups comprising government,

employer, and worker participants. The following questions were considered by each

group:

• what steps could be taken by governments, employers' and workers' organizations to

initiate, as quickly as possible, the ratification process of Convention No. 182?

• what role could each group play toward effective

implementation of the Convention?

Governments' views

The government representatives concluded that to initiate the ratification process,

national consultations with all members of society should be held with a view to

preparing a draft document on ratification for presentation to Cabinet. To prevent child

labour from spreading, improvements in the labour inspection functions of the ministries

of labour needed to be complemented by general improvements in education.

Workers' views

The workers' representatives stated that more awareness raising was necessary about the

worst forms of child labour which would lead to improved networking between relevant

actors. This had to be supported by enhanced data collection and the establishment of

national as well as regional monitoring systems that needed also to

target schools and workplaces. Trade unions in general should be used as fora for

lobbying, and teachers' unions, in particular, should be considered as potential monitoring

agents. Moreover, governments should be pressured to take a more proactive stance that

included the provision of improved employment opportunities for adults.

Employers' views

The employers' representatives agreed that in order to initiate the ratification process, the

relevant issues should be referred to the appropriate tripartite bodies for further study and

consultation. The private sector should lobby relevant government officials who should

recommend ratification of Convention No.182.

The ILO International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC)

The approach of IPEC

Mr. Frans Röselaers, Director of the International Programme on the Elimination of

Child Labour (IPEC) outlined the approach of the ILO to child labour. He pointed out

that the ILO had a three-pronged approach, namely standard setting, technical

cooperation and advocacy. Concerning technical cooperation, IPEC was the ILO's

`operational arm'. Thirty-three countries had signed a Memorandum of Understanding

since the programme's inception in 1992. Currently, 22 donors supported the Programme.

The structure of IPEC consisted of collaborative frameworks at both the national and sub-

regional level. Based on a Memorandum of Understanding, representatives of the

implementing government agencies, workers' and employers' organizations as well as

other non-governmental organizations formed a National Steering Committee (NSC). The

NSC together with a National Programme Coordinator, provided the key structure at the

national level. At the sub-regional level, technical advisers coordinated regional activities

with a special focus, such as on tourism in Eastern Africa, footwear in South Asia or

commercial agriculture in Southern and Eastern Africa.

Goals and steps of IPEC

IPEC's strategy is multi-sectoral and phased. Its aim is to strengthen the capacity of

partner organizations to address the complex child labour problem. Its goals and steps

include:

• motivate ILO constituents to engage in a dialogue on child labour and to create

problem solving alliances

• carry out situational analyses to document the nature and magnitude of child labour in

a given country

• assist the concerned parties in devising national policies to address specific child

labour problems

• strengthen the existing organizations and set up institutional mechanisms to guarantee

national `ownership' of the programme on child labour

• create greater awareness of the problem in the community and at the workplace

• promote the development and application of protective legislation

• support direct action with (potential) child workers to demonstrate that it was possible

to prevent children at risk from entering the workforce prematurely and to withdraw

working children from exploitative and hazardous work

• reproduce and expand successful projects in order to integrate their strong points into

the regular programmes of a country's social partners

• integrate child labour issues systematically into social and economic development

policies, programmes and budgets

In view of the complex nature of child labour and the difficulty of eliminating it

overnight, IPEC gave top priority to ending the worst forms of child labour. Priority

action concerned children working under forced labour conditions or in bondage, children

in hazardous working conditions and children who were particularly vulnerable, such as

very young working children under 12 years of age.

ILO's Statistical Information and Monitoring Programme on Child Labour

(SIMPOC)

SIMPOC was created to improve the information base and data collection methodology

on child labour. SIMPOC was launched in 1998 as an interdepartmental programme,

managed by IPEC with technical assistance from the ILO's Bureau of Statistics, to assist

its member countries in establishing the following:

(a) a programme for the collection, use and dissemination of tabulated and raw

quantitative and qualitative data that allows for the study of the scale, distribution,

characteristics, causes and consequences of child labour

(b) a basis for child labour data analysis which would be used in planning, formulating

and implementing multi-sectoral integrated interventions, monitoring their

implementation, and assessing the impact of policies and programmes

(c) a database on child labour consisting of quantitative and qualitative information on

institutions and organizations that are active in this field, child labour projects and

programmes, industry-level action, and national legislation and indicators which would

be updated on a continuing basis whenever new information became available

(d) comparability of data across countries

Cooperation with other agencies

The ILO was actively exploring the possibilities for enhanced joint action as well as

capacity building with UNICEF. A framework had been developed for a joint

IPEC/UNICEF inter-regional initiative on child labour in domestic service. A project on

data collection and analysis of child labour would soon start operations under the

auspices of the ILO, UNICEF and the World Bank.

IPEC in the Caribbean

In closing, Mr. Röselaers summarized areas for potential IPEC support as follows:

a) networking, social mobilization and sub-regional initiatives

b) research and the identification of the worst forms of child labour

c) country programmes

Part four: Regional and national trends and experience

UNICEF: The socio-economic experience of children in the Caribbean

The Representative of UNICEF in Jamaica, Ms. Afshan Khan, quoted ILO estimates for

1995, where some 7.6 million children between the ages of 10-14 were thought to be

working in Latin America and the Caribbean. She argued that there were several reasons

for the participation of children in labour and that poverty was not sufficient to explain

child labour. Other factors, such as cultural norms and attitudes affected the perception of

the role of children. Furthermore, from a political point of view, child labour existed

simply because neither the state nor civil society had done enough in terms of policies

and programmes for eradicating it.

In the Caribbean, global economic trends, such as the looming collapse of preferential

trade and a decline in the competitiveness of major agricultural exports were leading to

unemployment and other manifestations of social disintegration. Other factors affecting

increases in poverty included increased competition in the light manufacturing sector,

serious deficiencies in human skills development, inadequacies of existing safety nets,

restricted access to traditional emigration centers as well as the emergence of a violent

drug culture. Moreover, the quality of education was increasingly being questioned as

performance indicators for school leavers continued to be poor and the acquisition of

skills minimal. The problem partly rested with the school curriculum and instructional

methodologies which were often irrelevant to the life experiences of Caribbean children.

Child labour, therefore, was the result of the interplay between complex macroeconomic

trends, inadequate legislative frameworks and institutions, and socio-economic family

circumstances.

Existing poverty assessments and some of the situation analyses done by UNICEF

indicated that there was a correlation between certain high risk groups affected by

poverty and the incidence of child labour. High risk groups included rural landless

farmers, single female-headed households and urban squatter communities. Children in

rural communities, especially those in banana producing states, often helped with

agricultural work and frequently had only limited access to school. Single female-headed

households were prevalent throughout the region and circumstances sometimes required

girl children to stay at home to take care of younger sibllings while mothers went out to

work.

By way of further examples, Ms. Khan referred to urban squatter communities in Guyana

where children had increasingly turned to the streets and also reports about child

prostitution in Trinidad and Tobago. She also pointed to both Saint Vincent and the

Grenadines and Dominica where children were said to be scavenging from solid waste

dumps, and Suriname where documented evidence existed of children engaged in

economic activities. In 1994, results from an National survey on child labour in Jamaica

(incomplete) revealed that 4.6 per cent, or just over 22,000 children under age 16 were

working.

Ms. Khan said that work which exposed children to exploitative forms of labour (such as

full-time work at too early an age, work which exerted undue physical, social or

psychological stress, or work which hampered access to education) threatened their full

social and psychological development. On the contrary, light work that involved

activities whereby children acquired life skills or improved their nutrition and self-esteem

could be beneficial. However, the denial of the basic human right to freedom and dignity

posed a serious risk to social investment since such children might well be incapable of

assuming responsible social roles in the future. Consequently, the United Nations

Convention on the Rights of the Child, the ILO Minimum Age Convention (No. 138),

and the ILO's new Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (No. 182) were the essential

bases for guiding policy and protecting children from such work.

Ms. Khan stated that there was a serious deficiency in child labour-related research and

data collection in the Caribbean. She characterized the regional data situation as not

reliable, comparable nor periodic in nature. She underlined the strong interest in creating

a module for household surveys to collect pertinent information on the subject and to

systematize the dissemination of statistics. However, in addition to monitoring

compliance with existing agreements, specific research projects were needed to identify

alternatives to rural and domestic child labour in the region.

As elements of a necessary strategy, Ms. Khan proposed legislative reviews for

harmonization of existing laws, the stimulation of micro-enterprise development and

other forms of assistance in vulnerable communities, targeted support for underachieving

students at primary level or out-of-school youth, and greater advocacy for the

enforcement of existing legislation on compulsory education and child labour. In closing,

she called for a broad multi-pronged programme surpassing conventional partners with

the overall objective of promoting a culture of rights and alliances to protect children

from all forms of hazardous work.

Working with street children in Jamaica: The experience of Children First

Ms. Claudette Pious, Executive Director of the non-governmental organization, Children

First, summarized its origins and approach. She pointed out that Children First was

Jamaica's largest NGO working with "children out of place". It pursued a holistic

approach in its attempt to improve the life chances and rights of children.

With the input of the children, Children First assisted in devising `personal plans' for the

children. The plans centered around remedial education programmes, counselling, youth

advocacy, environmental education and skills training. So far, about 648 children had

benefitted and the approach had successfully moved away from a focus on welfare to a

developmental one that aimed to get children better prepared for the global market place.

She called for a `cost-benefit-analysis' to measure the effects from children working

versus the costs of supporting initiatives such as Children First.

Ms. Pious warned that some of the worst forms of child labour, such as child prostitution

and drug pushing, were a sad reality. According to her assessment, in Jamaica, much of

this might occur in the context of minors involved in "go go dancing" or the sexual

exploitation of domestic workers. Therefore, the preventive work of Children First

included an apprenticeship programme and entrepreneurial training such as hairdressing,

photography, sewing, art and crafts. The programme also provided information about

sexually transmitted diseases.

In the past, the Government of Jamaica, the United States Agency for International

Development, the Embassy of the Netherlands, UNICEF and Save the Children, among

others, had contributed to the programme. Despite seasonal support from community

members and other income-generating activities, financial difficulties persisted. In

closing, Ms. Pious expressed her willingness to have the experience of Children First

explored as a potential model for the region.

Child labour in the Caribbean: Country profiles

Ms. Suné Bethelmy, representing the Ministry of Labour and Co-operatives from Trinidad

and Tobago, chaired a panel discussion with representatives from Belize, Guyana and

Jamaica, who made presentations on their country experiences concerning child labour.

This was followed by discussion and summaries of the situation in the other countries

represented at the Meeting.(8)

Belize

Ms. Margarita Burrowes noted that while Belize had not ratified the ILO's Minimum

Age Convention (No. 138), the general principles were recognized in the Families and

Children's Act.(9)

The age for compulsory schooling covered those between the ages of five and 14.

However, she identified the main challenge for Belize as the lack of reliable statistics on

working children and sufficient manpower in the Labour Department to monitor the

situation. Furthermore, no available programmes for drop-outs from primary schools

existed and the situation of migrant children compounded the problem.

As reported in the country paper prepared for the Meeting, it was the general belief that

there was a problem of child labour in Belize. This impression, however, was based on

mere observation of children's activities and available statistical information on the

educational status of children in Belize. Especially in rural areas, children were reported

to be engaged in agricultural work in the sugar cane, citrus, bananas and rice industries,

on small family farms/plots and in small businesses.

The Government of Belize viewed the situation with grave concern since the

development and welfare of the country depended to a great extent on its ability to

provide the highest possible level of education and skills training for the young

population. As of April 1999 persons below the age of 18 years comprised 50 per cent of

the population.

The diverse cultural and ethnic composition of Belize society had also complicated the

issue of child labour and other child-related social problems. For instance, in both the

Mayan Indian and the Mennonite communities, children had traditionally been brought

up to participate in agricultural work and other family chores. Many of the new

immigrants formed part of the large informal sector of vulnerable people. The number of

children from this diversified population had not been ascertained.

The basic principle of the effective abolition of child labour was recognized by virtue of

the Labour Regulations, the Families and Children's Act as well as the Education Act.

Child labour as defined in the Labour Regulations referred to any person below the age of

14 engaged in employment and this would be considered an offense. The Labour Act

extended the definition to dangerous work which meant any occupation likely to be

injurious to a person's life, limb, health or education, depending on his or her physical

condition.

The National Committee for Families and Children (NCFC) was set up in 1994 as a

special advisory body to the Government on services and support for families and

children. The NCFC is an advocate for children and is expected to monitor the progress

of Government and civil society towards meeting the goals of the United Nations

Convention on the Rights of the Child and the World Summit for Children.

The Government and its social partners advocated that to address the problem of child

labour in Belize, further research needed to be carried out to determine the extent of the

problem. With the assistance of the ILO, they hoped that a child labour survey would be

carried out in October, 2000 and would consist of quantitative as well as qualitative

information on children's activities.

Jamaica

Ms. Glenda Simms presented the situation in Jamaica based on the country paper which

had been produced in consultation with the social partners. Jamaica had created the

position of an Ambassador for Children within the Ministry of Health and had embarked

upon the streamlining of existing laws. The Jamaican tripartite delegation at the

International Labour Conference had strongly supported the adoption of ILO Convention

No. 182.

Jamaica had made significant improvements in the quality of and access to education for

the majority of its population. However, according to the 1997 Jamaica survey of living

conditions, although enrolment rates were high, 95.7 per cent at primary level, there

continued to be a disparity in enrolment and attendance rates between children of the

poorest and wealthiest consumption groups. Another survey in Jamaica found that 4.6 per

cent, or 22,000 children under age 16 were active in the labour market. Some child

labourers were as young as six years old. Information on street

children was more difficult to obtain, but the findings from special

interviews conducted with persons and organizations working with street children

indicated that as of 1993 there was an estimated 2,500 street children. It was believed that

this number had increased dramatically. Boys between the ages 6-17 made up the

overwhelming majority of this group. Dr. Simms pointed out that the majority of the

working children were from poor backgrounds and of African decent which was a socio-

political issue that could not be disassociated from the situation of their mothers.

In Jamaica, girls were generally less visible in the labour market. They supplied labour

for mainly household tasks. Some girls, however, could be seen in markets working

under the watchful eyes of a guardian. It was widely assumed that some of the children

were engaged in commercial sexual activity, especially in the tourist areas. Ms. Simms

argued that some local institutions, such as the `Go Go Clubs' should be looked at more

carefully, but that child labour in the Caribbean, and in Jamaica in particular, might not

fall within the "worst case" scenario. However, she called for an end to the cultural and

psychological barriers that prevented Jamaican society from addressing such issues and

urged the Government to take the lead.

Finally, Ms. Simms made it clear that the ratification of ILO Conventions was just the

first step and that the Government should be held accountable through the engagement of

civil society. Moreover, employment creation and a careful gender analysis had to be part

of the struggle against child labour. Likewise, this had to be complemented by education

reforms and better support programmes.

Guyana

Ms. Charlene Parris-Sinclair presented the country paper on Guyana. Guyana had

ratified the ILO Minimum Age Convention (No.138) and was a signatory to the United

Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Guyana's legislation defined a child as "a

person under the age of fifteen years" in the Employment of Young Persons and

Children's Act. This Act stipulated that no such person should be admitted to

employment. Accordingly, the Education Act as well as the Factories Hours and Holidays

Amendment Act had recently been amended to adjust the age from 14 to 15 years.

However, Ms. Parris-Sinclair pointed to remaining gaps in the relevant legislation which

a tripartite forum under the leadership of the Ministry of Labour was now reviewing.

In addition, the country paper emphasized the need for comprehensive data collection on

all forms of child labour as documented evidence was still lacking. In 1999, a national

forum looking at available statistical information on the subject had endorsed the need for

an improved database. It seemed clear that despite compulsory schooling until the age of

15, the phenomenon of street children, including cases of teenage prostitution were

increasing. This was recently confirmed by a situation analysis of children in especially

difficult circumstances. In spite of a mass rehabilitation effort for schools, average drop-

out rates continued to be comparatively high for secondary schools (1997/98: 6.2 per

cent) and student absenteeism had increasingly given reason for concern. Large

student/teacher ratios and the lack of qualified teachers added to the problem. Moreover,

many female-headed households relied on children to take care of younger siblings and to

help with household chores. Thus, all forms of child labour were of great concern to the

Government, workers' and employers' organizations in Guyana, which were determined

to prevent further social disintegration.

Antigua and Barbuda

In the report of Antigua and Barbuda, no reported incidents of child labour were

mentioned. Both primary and secondary education were said to be accessible, free of

charge, and the Labour Code effectively guaranteed protection for children up to age 16.

Legally, a child was defined as "a person under the age of sixteen years" and the law

provided that "no child shall be employed or shall work in a public or private agricultural

or industrial undertaking". However, according to the participants from Antigua and

Barbuda, the situation would require a reassessment in light of the deliberations of the

Meeting, as the possibility for child prostitution or drug trafficking could not be ruled out

in an economy based almost entirely on tourism.

Grenada

The experience of Grenada revealed no official evidence of child labour. The compulsory

schooling age was 5-16 years. The Employment of Women, Young Persons and Children

Act (1990) prohibited the employment of children except for work being done in

recognized schools, under certain protective conditions or when the establishment was

owned by the family.

However, a lack of relevant statistics, as well as a chronic lack of secondary school

places and regular incidents of children dropping out of school due to financial

constraints, indicated potential problem areas. Furthermore, there were unconfirmed

reports of children assisting their parents in the agricultural industry and of children being

absent from school to sell agricultural produce during normal school hours. In order to

assist poorer families, a number of agencies sponsored students both in primary and

secondary schools, and the Government operated a school-feeding programme.

Suriname

The country report of Suriname revealed that under the Compulsory Education Act,

children between the ages of 7-12 had to be in school. Child labour, with or without

payment, was prohibited in Suriname under its Labour Act. It also prohibited children

from working outside an undertaking, except:

• in the family household of the child, at schools, in working places, in nurseries, in

educational institutions and similar institutions provided that the activities had an

educational character and were not for financial profit

• in agriculture, horticulture and cattle-breeding for family needs

Article 18 of the Act stated that children who had passed the age of compulsory

education could perform certain activities, to be decided by law, provided that these

activities were necessary to learn a job, or were by their nature to be done by children.

They could not, however, be allowed to do work which was too physically or mentally

demanding, dangerous or risky.

Nonetheless, children were thought to be active in economic activities, especially in the

informal sector, in fishery, child care and agriculture. The situation was not considered a

problem until recently and because of its limited extent. In the last few years, however,

the phenomenon of child labour had received the special attention of the social partners

and incidents of child prostitution had been detected. These activities, together with gold

mining, were the direct result of the deteriorating national economy. A preliminary child

labour survey had identified increasing poverty as the main cause. The Government had

already stated that there were no obstacles to ratifying ILO Convention No. 182.

Trinidad and Tobago

In Trinidad and Tobago, the two core pieces of legislation concerning children and

employment were the Education Act and the Children Act. The Children Act provided

that a child less than 12 years could not be employed; persons under 14 years were not to

be employed in any public or private industrial undertaking or on vessels. Further,

Section 91 stated that children under 14 years could not be employed in any enterprise

other than a family undertaking. The Education Act required compulsory attendance at

school up to age 12. However, pursuant to the regulations of the Statistics Act, the

minimum age of 15 years was used for the purpose of the collection and analysis of

labour force surveys.

In spite of these provisions, there were children within all age groups who were outside

the school system. For those in the 5 to 11 age cohort, the 1995 data from the Ministry of

Education gave an enrolment ratio of 89.1 per cent. In addition, in 1997/98 a total of

1,629 students had dropped out of the primary and secondary school system. A study

entitled The situation analysis of children in especially difficult circumstances in

Trinidad and Tobago (1993) provided statistical evidence that child labour was on the

increase. There were approximately 770 child workers under the age of 14 who were

employed in activities such as street vending, mechanic and tire repairs, furniture making

and so on. Furthermore, the numbers of street children were said to be visibly increasing

and these were both male and female, with the majority being male. A few of the cases

revealed the existence of child prostitution.

In its initial States parties report (1995) to the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the

Government of Trinidad and Tobago noted that "no mechanisms exist for the continuous

collection of statistical and other data to inform policy formulation". Accordingly, a

project proposal was developed by the Ministry of Labour and Co-operatives in April

1998 to create an information database on child labour called a Child Indicators

Monitoring System. This project however, had not yet been implemented due to a lack of

funding.

In view of this and in an attempt to rationalize all the related laws, a Legislative Review

Committee had been established to assess all the various provisions. The output of the

deliberations of this Committee had been several draft pieces of legislation which had yet

to be tabled in Parliament for discussion. They included The Miscellaneous Provisions

(Children) Bill, 1999 that proposed to raise the age of a child from 14 to 18 years. The

Children's Authority Bill, 1999 proposed that a central authority be established under

whose jurisdiction would be placed all persons under the age of 18. It would be an

independent body subject only to the lawful directives of the Minister responsible for

Social and Community Development. The proposed mission of the authority would be to

ensure that a coordinated and integrated package of social services, both preventive and

curative, was provided for all children and their families. Notwithstanding these efforts,

the challenge was for government agencies, employers' organizations, trade unions and

NGOs to come together and form a broad alliance against child labour.

Saint Kitts and Nevis

In Saint Kitts and Nevis, figures for child participation in the workforce were not

available and it was thought to be negligible because of the existence of protective

legislation. However, the country paper acknowledged that the risk for exploitation was

ever present and listed possible areas such as agriculture, domestic service and illicit

activities in which juveniles could find work and as a result were put at risk. Many

families in rural areas engaged in livestock farming and vegetable production. Children

were often required to assist in these activities as part of the family effort at subsistence.

This involvement, except for a few cases, was not seen to have a negative impact on their

educational status and achievement.

Concerning domestic service, children, particularly girls, may often engage in child

labour. It could be family oriented, where the children were made to look after younger

siblings or ailing parents and grandparents at the expense of their schooling. They might

also be engaged in other households as domestic servants or baby-sitters where they

could be exposed to dangerous situations. By far the greatest threat to this vulnerable age

group, however, was the potential for their involvement in illicit activities. These

included housebreaking and larceny, distribution of drugs, pornography and prostitution.

As far as national legislation was concerned, the question of child labour was addressed

in the Employment of Women, Young Person and Children Act and the Employment of

Children (Restriction) Ordinance. These Acts defined a "child" as a person under 14

years of age and made provision for the protection of children from work situations

which were hazardous to their health and development. Although, in Saint Kitts and

Nevis, the compulsory age for education was ages 5-16 years. The Department of Labour,

under the Labour Ordinance provided a monitoring mechanism as far as direct

employment of child labour was concerned, and labour officers had the power to

investigate any abuses which might come to their notice.

General discussion

In the general discussion, Mr. Geir Myrstad (IPEC) highlighted the importance of

targeted support for women's (self-)employment when working children were removed

from work. Early childhood care needed to be addressed as well. He warned that past

studies had indicated that tourism-based economies often presented a special risk for

child labour. Important legislative protective measures included the freedom for trade

unions to act as watchdogs over contractors, to ensure that they abstained from using

child labour in their operations.

Another ILO programme "Action against child labour through education" was also

discussed. It emphasized preventive measures. The programme included the following:

• mobilizing teachers and other educators

• intervening through formal and non-formal education to keep children in school

• building strong national alliances that make the prevention of child labour one of the

primary goals of the education agenda

• closing the gap between primary and secondary schooling in order to avoid producing

`children who have been dropped out'

Group work - National programmes of action

The following questions were discussed in three separate tripartite groups (10):

• What is the envisaged timetable for ratification of the ILO Worst Forms of Child

Labour Convention, 1999 (No.182)?

• What intergovernmental and consultative bodies are necessary to ensure effective

implementation of the new Convention?

• What should be elements of national programmes of action under Convention No. 182

and its accompanying Recommendation No. 190?

• What should be included in the conclusions and recommendations coming out of the

Meeting?

The group presentations showed agreement on the following major points: The timetable

for ratification of Convention No. 182 should be by the end of 2000. Effective

implementation required an intergovernmental approach in which the ministries of labour

had an important and leading role to play. Representation from the Ministries of

Education, Finance, Planning, Social Welfare, as well as from non-governmental

organizations would also be crucial. Trade unions and employers' organizations should

render support. Media campaigns, as well as national consultations should provide the

framework for effective dissemination of information. Countries should not stop short of

ratifying or improving implementation of Convention No. 138. Efforts to gather relevant

data and information needed to be strengthened. However, no country should wait until

all data had been collected or the education system fully improved, if children were

engaged in any of the worst forms of child labour since these would require immediate

action.

Programmes of action should include awareness-raising measures, pilot activities,

research and documentation as well as the prosecution of offenders. New policy

strategies should be centered on prevention, rehabilitation and evaluation. Social dialogue

mechanisms as well as national inspection systems needed strengthening. Policy

suggestions found in Recommendation No.190 were all considered highly relevant and

technical assistance from the ILO would be sought. Special consideration should be given

to the informal sector and employment creation for women.

(8) Antigua and Barbuda, Belize, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago presented country papers

to the Meeting on which the country profiles are based. The discussion on the child labour situation in the Caribbean was guided by the

following questions -- What kinds of child labour exist and what are the differences in the situation of boys and girls? What legal and practical

measures are already in place? What areas do law and enforcement not yet cover?

(9) The Government of Belize has since ratified Convention No. 138 and declared 14 as the minimum age.

(10) The composition of the groups were Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago (I); Antigua and Barbuda, Grenada, Saint Kitts and Nevis

(II); Belize, Guyana, Suriname (III).

Part five: Conclusions of the Meeting

The Meeting reached consensus on the following conclusions:

1. Convention No. 182 should be ratified by the end of the year 2000. The participants

agreed to inform their respective ministers and constituents about the programme of the

Meeting with a view to urging the members of national tripartite committees to

recommend ratification of Convention No. 182. Those countries that were already in the

process of ratifying Convention No. 138 were urged to bring Convention No. 182 into the

process. In addition, the outcome of the Meeting should be brought to the attention of the

Council of Human and Social Development of CARICOM as well as to the next Meeting

of Caribbean Ministers with responsibility for Labour.

2. A strong lead agency in government was needed to make the prevention of child labour

its principle cause. Ministries of labour would generally fill this role. Yet, the elimination

of child labour and its worst forms also required the involvement of many agencies and

support from civil society as well.

3. National efforts for awareness-raising were needed to generate greater commitment

and should involve schools as well as the wider community.

4. Further data collection and in-depth research was crucial. The cooperation of the

central statistical offices should be sought to carry out surveys, conduct rapid assessments

or develop modules as part of the 2000 census.

5. Preventive measures needed to be devised around structural improvements in

educational systems. Immediate action should include the rehabilitation or counselling of

children found to be engaged in the worst forms of child labour as well as the prosecution

of offenders.

The ILO Caribbean Office was requested to provide institutional support to ministries of

labour, assistance with the promotion of Conventions No. 182 and No. 138, research and

general awareness-raising. IPEC indicated that it would support such ILO activities in the

Caribbean. Furthermore, the ILO constituents were invited to explore the realization of

national action programmes, spearheaded by pilot activities and supported by sub-

regional activities. The ILO Caribbean Office stood ready to assist national information

campaigns with material, and possibly, the production of a short video.

Annex one: Introductory remarks

Willi Momm, Director, ILO Caribbean Office

As our discussions on the issue of child labour in the Caribbean begin, the Seattle

meeting of the WTO has concluded without achieving its objective of advancing the

framework for global free trade. One of the issues that contributed to the failure of the

meeting was the unresolved question of the labour dimension of international trade.

Many leaders from this region have gone to Seattle with the hope that the WTO rules

could allow for greater fairness to the vulnerable economies. Some have gone there to

make sure that they are fair to the workers, hoping that efforts to establish a social clause,

which links trade rules to performance with respect to fundamental labour standards,

could be successful this time.

Others however, went to Seattle determined to prevent a social clause discussion. They

feel that labour issues should be de-linked from trade rules and they claim that the ILO

has a sufficiently strong mechanism to ensure the world's compliance with fundamental

labour standards. If the proponents of this view were right - and we hope they are - one

might indeed be inclined to deny the need for a social clause approach.

There is a third group, however. These are those countries and companies who want