EVALUATION OF THE INDIANAPOLIS MOBILE CRISIS ASSISTANCE TEAM

Report to the Indianapolis Ofce of Public Health & Safety and the Fairbanks Foundation

MARCH 2018

CENTER FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE RESEARCH

HORIZONTAL VERSION

CENTER FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE RESEARCH

VERTICAL VERSION

AUTHORS

Katie Bailey, Program Analyst, IU Public Policy Institute

Brad Ray, Director of the Center for Criminal Justice Research

334 N Senate Avenue, Suite 300

Indianapolis, IN 46204

policyinstitute.iu.edu

CENTER FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE RESEARCH

HORIZONTAL VERSION

CENTER FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE RESEARCH

VERTICAL VERSION

CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS

Eric Grommon, Senior Research Associate, IU Public Policy Institute

Evan Lowder, Research Associate, IUPUI School of Public & Environmental Affairs

Staci Rising Paquet, Research Assistant, Center for Criminal Justice Research

RESEARCH SUPPORT

Spencer Lawson, Research Assistant, Center for Criminal Justice Research

Joti K. Martin, Program Analyst, IU Public Policy Institute

Elle Yang, Graduate Research Assistant, IU Public Policy Institute

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

KEY FINDINGS

BACKGROUND

LITERATURE REVIEW

INDIANAPOLIS MOBILE CRISIS ASSISTANCE TEAM

STUDY DESIGN

Focus Groups

Interviews with Stakeholders

Field Observations

OfcerSurvey

MCAT Response Data

BARRIERS AND FACILITATORS TO MCAT IMPLEMENTATION

Barriers to Program Implementation

Policies and Procedures

External Coordination

Outpatient Resources

RoleConictandStigma

Facilitators to Program Implementation

Initial Citywide Collaboration and Buy-In

Information Sharing

Team Building

IMPD EAST DISTRICT OFFICER SURVEY

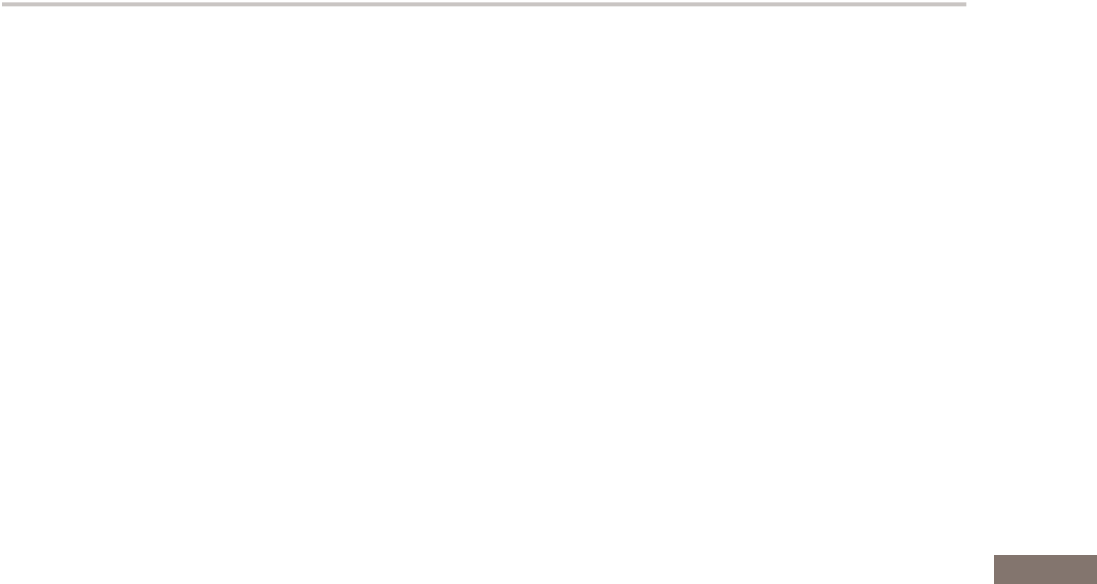

Exhibit 1: Clarity of Roles and Expectations of the MCAT Unit

Exhibit 2: Perceptions of MCAT Usefulness

QUANTITATIVE DATA ON MCAT RESPONSES

Client Demographics

Exhibit 3: Demographic Characteristics of MCAT Response Cases

Reason for Response

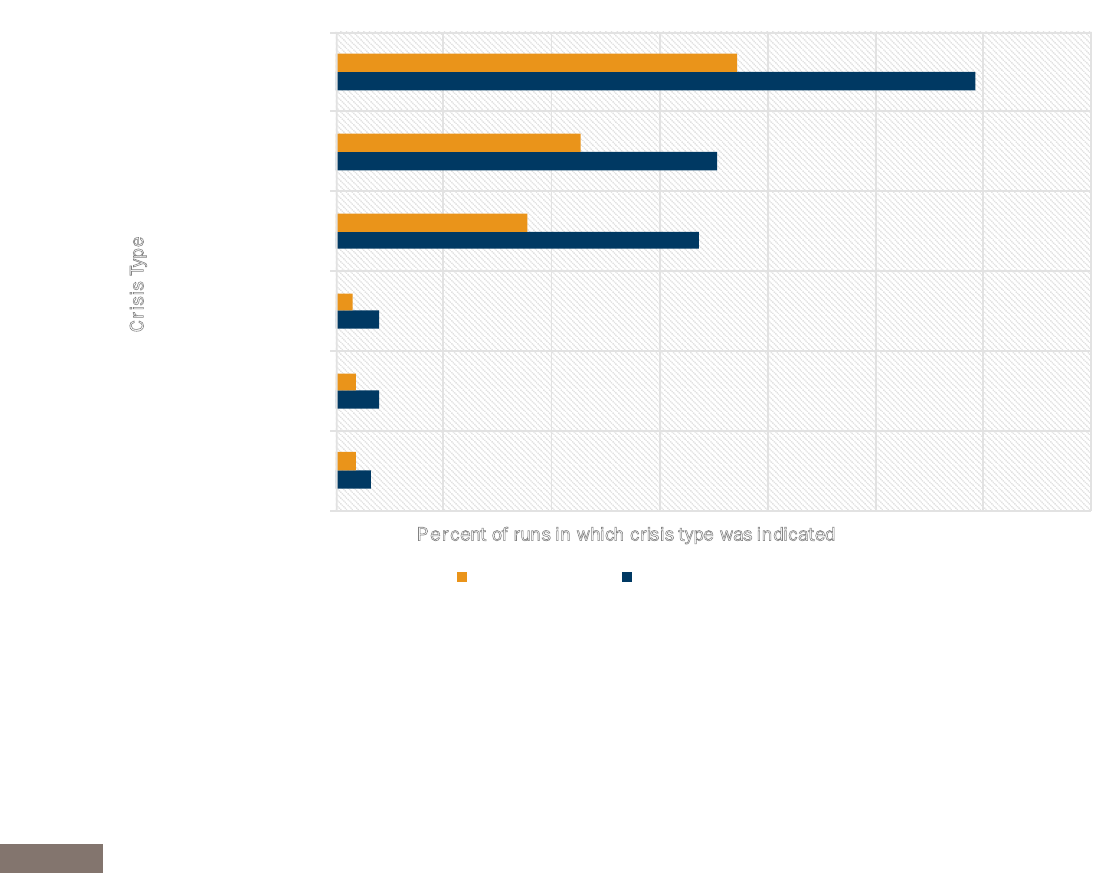

Exhibit 4: Reasons for MCAT Response

Exhibit 5: MCAT Response Types over Time

Scene of an MCAT Response

MCAT Response Outcomes

Exhibit 6: MCAT Response Outcomes

Repeat Encounters

Exhibit 7: MCAT Repeat Encounters

Differences by MCAT Units

Exhibit 8: Variation by MCAT Units

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

REFERENCES

1

1

2

3

5

6

6

7

7

7

7

8

8

8

8

9

10

11

11

12

13

13

14

14

16

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

19

20

20

21

22

24

1

In May 2016, Indianapolis Mayor Joe Hogsett formed the Criminal Justice Reform Task Force to address,

amongotherissues,thesignicantnumberofindividualsenteringthecriminaljusticesystemwithmentalhealth

or substance abuse issues. This resulted in the establishment of a Mobile Crisis Assistance Team (MCAT) pilot

program that integrated police, paramedics and mental health professionals into teams to respond to emergency

calls involving people with behavioral health and/or substance use issues. The pilot program aimed to divert

thosepeopletomentalhealthandsocialservicesinsteadofthecriminaljusticesystem,andtorelieveother

rst-respondersfromthesceneofthesetime-consumingandcomplicatedemergencysituations.TheMCATpilot

began in the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department (IMPD) East District.

The Center for Criminal Justice Research at the Indiana University Public Policy Institute evaluated the pilot

program using data from MCAT run reports between August 1 and December 9, 2017. Additionally, East District

IMPDofcersweresurveyed,keystakeholdersandprogramdesignerswereinterviewed,focusgroupswere

heldwiththeMCATteammembers,andeldobservationswerecompleted.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• MCATtransportedapersontojailinlessthan2%ofallresponsesduringthepilot

• MCATunitswereabletorelieveoneormoreotherrstresponseunitsfromthesceneofan

emergency in two-thirds of all runs during the study period

• ThemajorityofMCATencounterswerecompletedinunder90minutes-Inencountersthat

tooklongerthan90minutes,MCAThadrelievedotherrstresponseunits80%ofthetime

• MCATunitsencounteredasmallsubsetof“frequentyers”—individualsreceivingmultiple

MCATresponsesduringthestudyperiod—whoweremorelikelytobegravelydisabledand/

or have mental health issues than those who had only received one MCAT response

• Eighty-vepercentofIMPDEastDistrictpoliceofcerssurveyedindicatedtheMCATunitwas

very useful or extremely useful to them as an additional resource in responding to emergencies

• One-thirdofIMPDEastDistrictpoliceofcerssurveyedindicatedbeinginterestedinserving

asanMCATofcerinthefuture

• A lack of outpatient treatment options and clear policies and procedures appeared as the

most salient barriers to implementation of the MCAT pilot program

• Access to and triangulation of collaborating agency information on persons experiencing

emergencies;supportfromcityofcials;andteambuildingexercisesduringMCATtraining

emerged as the most salient facilitators to implementation of the MCAT pilot program.

KEY FINDINGS

2

AccordingtotheMarionCountySheriff’sOfce,approximately40%ofdetaineesinMarionCounty’sjailsat

any one time suffer from mental illness, resulting in $8 million of medical care and services annually (McQuaid,

2015). In addition, roughly 85% of detainees with a mental illness are also diagnosed as suffering from

substanceabuseissues(McQuaid,2017).Thepastveyearshaveshownanalarmingincreaseinpoliceand

emergency medical service runs involving individuals suffering from mental illness and drug addiction. Although

lawenforcementexpertsestimatethatasmanyas 7%to10%ofpatrolofcerencountersinvolvepersons

withmentalillness,historicallypoliceofcersreportfeelingillequippedtorespond(Deane,Steadman,Borum,

Veysey, & Morrissey, 1999).

In May 2016, Indianapolis Mayor Joe Hogsett formed the Criminal Justice Reform Task Force. In December of

thatyear,theTaskForceissuedacomprehensiveplanforcriminaljusticereformthatincluded,amongother

initiatives,divertingpersonssufferingfrommentalillnessandaddictionawayfromthecriminaljusticesystem

and into evidence-based treatment and services, when appropriate.

This resulted in the establishment of a Mobile Crisis Assistance Team (MCAT) pilot program, an integrated

co-responding police-mental health team model with the addition of a medical professional. The MCAT pilot

began August 1, 2017 with four teams operating within the boundaries of the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police

Department(IMPD)EastDistrict.TheMCATteamsconsistofspecially-trainedpoliceofcers(IMPD),paramedics

from Indianapolis Emergency Medical Services (IEMS), and crisis specialists from Eskenazi Health Midtown

Community Mental Health (Midtown). The pilot program aimed to divert time-consuming, challenging, and

complicated pre-arrest situations to a dedicated, specially-trained team that could better assess and engage

individuals,routingthemtomentalhealthandsocialservicesinsteadofthecriminaljusticesystem.

TheIndianapolisOfceofPublicHealthandSafetypartneredwiththeIndianaUniversityCenterforCriminal

Justice Research (CCJR) of the Indiana University Public Policy Institute (PPI), to provide an evaluation of the

MCAT pilot program. This evaluation was based on an expansion design where evaluators used a mixed-methods

approach to extend the scope, breadth, and range of inquiry (Greene, Caracelli, & Graham, 1989). In this

approach, qualitative methods are generally used to assess program implementation and quantitative methods

to assess program outcomes. For the MCAT evaluation, qualitative data collection included: focus groups with

MCATunits,interviewswithkeyprogramdevelopersandcommunitystakeholders,eldobservationswithan

MCATunit,andasurveyofEastDistrictpoliceofcers.QuantitativeanalysisexaminedMCATresponsedata

provided by MCAT units. The primary purpose of qualitative data collection was to better understand barriers

and facilitators to program implementation, while quantitative data points from MCAT runs were developed

using a program-theory approach whereby the measures captured are based on stakeholder beliefs regarding

the important outcomes of the pilot program.

This report begins by providing an overview of the academic literature on the challenges presented by persons

withamentalillnessandco-occurringsubstanceusetopoliceofcersandthecriminaljusticesystemasawhole,

along with efforts to mitigate these challenges. Next, this report describes the MCAT pilot program in greater

detail before presenting the study design and results. Implications for research and future pilot programs are

discussed.

BACKGROUND

3

Sincethe1970s,personswithmentalillness(hereafter,“PMI”)havebeenhandledincreasinglybythecriminal

justicesystem,aprocessreferredtoasthe“criminalizationofmentally-disorderedbehavior.”Manysuspect

that deinstitutionalization contributed to increases in the incarceration of PMI (Lamb & Grant, 1982; Stelovich,

1979; Swank & Winer, 1976; Whitmer, 1980), as these individuals were no longer in hospitals, but out in the

communityandatriskofarrest(Whitmer,1980).Today,PMIarethreetimesmorelikelytobeinjailorprison

thaninahospitalreceivingappropriatetreatment(Taheri,2016).Thisislargelybecausethecriminaljustice

system is the only social institution that cannot turn away these cases. Private centers can refuse to treat patients

theydeemtoberiskyordisruptive;communitymentalhealthproviderscanrejectthosewhohaveacriminal

history; and hospitals can turn away those who appear threatening or intoxicated.

Criminal justice systems across the country have responded by developing programs aimed at reducing

incarceratedPMIbydivertingthemawayfromthecriminaljusticesystemandintocommunity-basedtreatments

andservices.Servicesprovidedbymanyoftheseprogramsoccur“post-booking”(e.g.,mentalhealthcourts)

and can only be accessed once an individual has been arrested or charged with a crime. Many studies suggest,

however,thatthemosteffectivewayofdivertingPMIfromthecriminaljusticesystemisbyintervening“pre-

booking”aspoliceofcersrespondto911emergencycalls(Muntez&Grifn,2006).

Approximately 10% of law enforcement encounters involve PMI, about three quarters of whom have co-

occurringsubstanceusedisorders(Steadman,2005;Skubbyetal.,2013).Often,policeofcersdon’thave

the resources or training to handle mental health crises effectively, or the people who experience them. During

these encounters, PMI in crisis can exhibit strange or hostile behavior, creating a situational ambiguity that can

compromisethesafetyofofcers(Taheri,2016).Oneofthemostpopularresponsestothisissuehasbeenthe

implementationofCrisisInterventionTraining(CIT),wherepoliceofcersaretrainedaboutmentalillnessand

how to respectfully and safely interact with PMI (Dupont, Cochran, & Pillsbury, 2007; Compton, Bahora, Watson,

&Oliva,2008).Additionally,CITcurriculumalsoprovidestrainingforofcersonco-occurringmentalhealthand

substance use disorders that as many as three quarters of PMI experience (Steadman, 2005; Dupont, Cochran,

&Pillsbury,2007).EmpiricalevidenceonCIThasbeenencouragingandsuggeststhatCIT-trainedofcershave

more positive attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge about mental illness, and agencies with CIT programs have lower

arrest rates than other types of diversion programs (Compton, et al., 2008).

Even with the emergence of CIT programs, police agencies struggle to engage with PMI safely in the communities

they serve. To this end, several police departments have partnered with community healthcare providers to

create co-responding police-mental health teams, known alternatively as mobile crisis intervention teams, crisis

outreach and support teams, and ambulance and clinical early response teams (Shapiro et al., 2014). The

generalco-responseteammodelinvolvespartneringaswornpoliceofcerwithamentalhealthprofessional,

although many agencies create three-person teams by adding a medical professional (such as a nurse or

paramedic) or a peer specialist (such as an individual in recovery from mental illness or substance use disorder)

(Hay, 2015). Dozens of such teams currently operate in North America from Los Angeles, California to Halifax,

NovaScotia,andhaveseveralcommongoals,includingdivertingPMIawayfromthecriminaljusticesystemand

increasing consumer access to mental health and substance abuse treatment (Steadman et al., 2001; Shapiro

et al., 2014). However, one important distinction among these co-responding units is the timing of the response:

LITERATURE REVIEW

4

someunitsarerstresponderstothesceneofanemergencywhileotherunitsprovidefollowupafteramental

health or substance abuse crisis.

As these co-response programs are relatively new, only a handful of studies have examined the effectiveness of

thisapproach,thoughresultshavebeengenerallypositiveinndingthatco-responseteamsarecosteffective,

well-receivedbythecommunitiestheyserve,andreduceburdensonthecriminaljusticeandhealthcaresystems.

For example, a 2005 program evaluation of Victoria City (Canada) Police Department’s Integrated Mobile Crisis

Response Team found many positive outcomes, including increased crisis call response rates, decreased reliance

on hospital emergency rooms, and increased information sharing between agencies. The ndings, however,

suggesttheseoutcomesdependedonadequatestafng,appropriatevehicles,sufcientteammembertraining,

a centralized dispatch location, and access to pertinent medical and criminal histories about the PMI served

(Baess, 2005). In 2006, Hartford and colleagues used a mixed-methods approach and reviewed over seven

studiesandftytwopolicedepartmentsurveysfromthreecontinentsaboutpre-bookingdiversionprograms

(includingco-responding police-mental healthteams) and identiedfourkeyelementsthat wereassociated

with positive outcomes: involving all agencies in the program’s development, conducting regular meetings with

program stakeholders, creating a 24/7 no refusal policy for drop off centers, and appointing an individual to

act as a liaison between all agencies involved. A similar 2014 review by Shapiro and colleagues of over twenty

peer-reviewed studies, reports, and dissertations on co-response teams suggested that successful teams created

important bonds between PMI and community mental health resources while lessening the burden on the criminal

justicesystembymakingfewerarrestsandreducingtimeonsceneforrstresponders.

Finally, an evaluation of a mobile police-mental health crisis team in an urban setting by Kirst and colleagues in

2015 found that stakeholders felt that the program was meeting its goals of reducing criminalization of mental

illness and assisting PMI in crisis via positive partnerships between individual team members and their respective

agencies. Despite positive outcomes, however, several barriers to co-response program implementation are

consistently reported throughout the literature. Most importantly, all studies have reported that the lack of

a 24/7 psychiatric drop off location center with a no-refusal policy is a critical barrier to program success.

Additionally, there are recurring issues with role clarity and differences in professional cultures between team

membersascontributingtoimplementationdifculties.

5

TheIndianapolisMCATpilotprojectlaunchedonAugust1,2017asapolice-mentalhealthco-responseteam

modelwiththeadditionofamedicalprofessional.TheIndianapolispilotmodelconsistsofanIMPDpoliceofcer,

an IEMS paramedic, and a mental health clinician from Midtown. MCAT is based in and serves the IMPD East

District. This district was chosen because it ranks high on the Social Disorder Index and has high rates of mental/

emotional911callsandambulancerunsformedicalemergencies.Eachentityinvolvedidentiedacoordinator

withinitsleadershiptodesignandimplementtheMCATprograminconcert.Theseofcialcoordinatorsdeveloped

andimplementedtraining,identiedteammembersfromtheirrespectiveagencies,andmadeproceduraland

logistical decisions with support from the Ofce of Public Health and Safety. In preparation for launch, a

business associate agreement between the Health and Hospital Corporation of Marion County, of which IEMS

and Midtown are part, and IMPD was created to protect personal health information of those with whom the

MCAT teams come in contact.

FourMCAT unitswereformed forthe pilotproject,each working in12-hour shifts,resultingin 24/7 MCAT

availability. MCAT members have unique uniforms identifying them as both MCAT personnel and members of

their respective agencies. The teams operate out of a non-emergent van with an MCAT logo on the outside. Each

teammemberutilizestheirownlaptoptoaccessnecessaryagency-specicinformationandtheMCATvehicle

isadditionallyequippedwithamedicalequipmentbag,automatedexternaldebrillatorandstandardissued

IMPDequipment.MCATmaytransportindividualstoanemergencydepartment,otherassessmentcenter,orjail

when deemed appropriate.

OneaspectoftheMCATthatisespeciallyimportanttonoteisthatitisprimarilyarst-responseunit,nota

follow-upunit.Thus,theMCATmayrespondtothesceneofacrisisattherequestofotherrst-responders,

or self-dispatch upon hearing of a relevant crisis via IMPD or IEMS dispatch radio. However, when necessary,

MCAT may also conduct follow-ups with individuals they previously encountered to encourage linkage with

services.TherolesofMCATteammembersareuidtoallowforthemtoresponddynamically,butgenerally

theofcersensuresecurityatthescene;cliniciansfacilitatementalhealthassessmentsandtreatmentlinkage;

and paramedics address any medical issues, check patient vitals, and perform assessments related to substance

usesymptomswhennecessary.Ofcersandparamedicsareauthorizedtomaneuverthevehicleandanyofthe

three team members may input information regarding runs into the electronic data collection system.

The mission of the MCAT pilot program is to provide a real-time response to individuals in crisis by facilitating

assessment, triage, and linkage with appropriate services. In doing so, MCAT aims to (1) utilize alternatives to

arrests of citizens in behavioral health and substance use crises, when appropriate; (2) seek safe outcomes for

individuals, families, and public safety personnel during a crisis; (3) reduce the overutilization of emergency

services through linking individuals to appropriate support resources; (4) encourage utilization of appropriate

community-based support resources as an alternative to emergency room and inpatient hospitalizations; and (5)

decreasethetimeotherrstresponseunits(i.e.,police,re,andEMS)spendatthesceneofacrisisbyassuming

control when appropriate.

MCAT training was primarily developed by Midtown leadership and included classroom learning, stakeholder

and expert presentations, site visits, and police ride-alongs. Training included the following topics:

INDIANAPOLIS MOBILE CRISIS ASSISTANCE TEAM

6

1. Mental health overview – including CIT training for those who had not yet received it, study of the

mental health and treatment system, language use and stigma, and relevant legislation;

2. First person accounts – including input from individuals with experience in substance use recovery;

3. Legal and Risk management – – including discussion of relevant legal and ethical issues of inter-agency

informationsharingandoverviewofrelevantaspectsofthecriminaljusticesystem;

4. Clinical information – including training related to populations with behavioral health and substance

abuse issues as well as self-care;

5. Special populations – including topics related to persons with developmental disabilities and autism,

personsexperiencinghomelessness,theLGBTQpopulation,olderadults,sextrafckingandprostitution,

veterans, and youth and family issues;

6. IMPD related training–includinguseofforce,situationalawareness,drugandnarcoticidentication,

de-escalation strategies and street safety;

7. IEMS related training–includingrstaid,CPRandnaloxoneuse;

8. Faith-Based community solutions – including introductions to existing programs aimed at assisting

relevant populations; and,

9. Organizational team building.

The MCAT evaluation focused on barriers and facilitators of program implementation as well as outcomes

associated with crisis responses. Barriers are problems, setbacks, challenges or obstacles to program

development or implementation, whereas facilitators are support systems, synergies or bridges that made

program development or implementation easier. The evaluation included qualitative data collection from focus

groupswithMCATmembers,interviewswithkeystakeholders,andeldobservationsduringMCATresponses.

In order to examine MCAT crisis responses, CCJR researchers worked with key stakeholders to identify the

necessary data points and develop data collection protocols. The following types of data were collected for

this evaluation.

Focus Groups

CCJR researchers conducted two semi-structured focus groups with members of the MCAT units. Each focus group

consisted of two teams (six members in each focus group) and lasted approximately 2 hours each. There was

a broad interview guide that was used to facilitate these focus groups in a semi-structured manner, allowing

for diversion and probing when appropriate. One lead researcher guided the focus group and two additional

trained researchers took notes.

STUDY DESIGN

7

Interviews with Stakeholders

CCJR researchers completed nine, one-on-one interviews with MCAT program developers and stakeholders. This

included leadership personnel from IMPD, IEMS, the Indianapolis Department of Public Health & Safety, and

Eskenazi Health. Interviews followed a structured survey guide, were audio recorded, and lasted approximately

one hour each.

Field Observations

TwoCCJRresearchersconductedobservationsofanMCATunitviaa“ride-along”whichlastedapproximately

ve hours. This eld observation began in the MCAT ofce based at the IMPD East District Headquarters.

ResearchersthenaccompaniedtheMCATunitinthevantothreeseparateresponsesandtookeldnoteson

observations.

Qualitative data were transcribed and researchers reviewed transcripts using content analysis to identify

barriers and facilitators to MCAT development and implementation. To establish inter-rater agreement,

researchers individually coded three qualitative sources using NVivo qualitative analysis software, and met

again to discuss emerging themes around barriers and facilitators and to develop coding procedures for the

additionalqualitativesources.Uponindividuallycodingallqualitativematerials,researchersmetanaltimeto

reviewthemajorthemesgleaned.Majorthemesarethoseidentiedbyfourormoreindividualsfromatleast

two different agencies during qualitative data gathering.

Ofcer Survey

Inanefforttotriangulatethesequalitativeresults,researchersalsoconductedasurveyofofcersfromtheIMPD

East District in which MCAT operates. CCJR researchers developed a web-based survey using Qualtrics survey

softwaretosolicitknowledge,attitudesandopinionsofofcerswhosharethedistrictwiththeMCATunits.The

surveywasanonymousandsentviaemailtoapproximately140patrolofcerswhoweregivenonemonthto

complete the survey.

MCAT Response Data

Finally, the research team collected quantitative data on each MCAT crisis response. CCJR researchers developed

a database where MCAT members were responsible for inputting information for each response completed.

MCAT stakeholders assisted in designing these data collection points.

Quantitative data were imported into SPSS for statistical analysis. Analysis largely consisted of descriptive

statistics regarding MCAT responses, but variation in response and outcomes based on key measures were also

examined. To this end, CCJR researchers examined statistically signicant differences using t-tests and Chi-

square difference of proportion tests.

8

BARRIERS TO PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION

Policies and Procedures

Because the MCAT was established as a pilot program, little was known initially about the ways in which the

teams would most effectively address their behavioral health and substance use agenda. This was made more

problematic with the absence of detailed policies and procedures. As one team member noted,

“We need a clear mission statement; we don’t know whether we’re supposed to be

responding to certain runs or not. Right now we’re all taking different approaches to

these calls. What is our role supposed to be? Because I don’t think we have a clearly

dened role.”

However, leadership was hesitant to limit the ways in which MCAT could respond to emergencies, preferring to

allowforcreativityandexibilityintheirresponse:

“I think putting too many bright line rules on [this program] would probably be

detrimental to it. Because then it’s like when you have these bright line rules and

ofcers are held accountable to these rules they could get in trouble.”

WhilethisuidityallowedforMCATtocontinuouslylearnandadjusttoreal-timeneeds,alackofcleardirection

sometimes led to confusion and variation among the teams, both in this pilot program and previous co-response

programs studied in the literature. As noted by one MCAT stakeholder, “teams are inconsistent as far as their

operationsanddecisionmaking.”

BalancingtheneedsforuidityandconsistencyiskeyforfurtherclarifyingtheroleoftheMCATandcould

lead to greater buy-in from team members. For some, it is unclear whether they can or should perform duties

oftheirtraditionalroleswhileservingasanMCATmember.Greaterdenitionandclaricationofon-the-scene

procedures can help prevent team members from feeling underutilized. Additionally, determining to which

emergency situations MCAT should prioritize responding could lead to more consistency between teams and

greatercondencethatteamsaredoing“whattheyshould.”

Finally, developing common procedures and resources for post-crisis action can increase consistency between

teamsandreduceinefcienciesorconfusionfortheteamsindecidingwheretotakepatients,whotocontact,and

how to follow up. CCJR researchers witnessed evidence of at least one MCAT member who began the process of

consolidating phone numbers, addresses, forms, pamphlets and other resources for MCAT use. Formalizing and

regularly updating this consolidated information should be prioritized.

External Coordination

Inter-agencycoordinationcanbedifcultwhencombiningmultipleagenciesinoneemergencyresponseinitiative,

Inter-agencycoordinationcanbedifcultwhencombiningmultipleagenciesinoneemergencyresponseinitiative,

particularly around the topics of mental health and substance use. A culture shift is necessary for all entities

involved to both understand one another’s initiatives and coordinate a cohesive, appropriate response. IEMS,

IMPD and Midtown have taken strides to successfully coordinate; however, coordinating and communicating

MCAT goals and responsibilities with external actors was a salient barrier that emerged. For example, team

BARRIERS & FACILITATORS TO MCAT IMPLEMENTATION

9

members often recalled being asked who they were, noting that “People don’t know who MCAT is or what they

do.”MCATmembersstatedthatthisoccurredamongfellowofcersintheEastDistrictbutalsoamongotherrst

response agencies. For example, one MCAT stakeholder noted:

“[MCAT leadership] probably could have communicated it a little better amongst

supervisors and ofcers on East District, so they had a better idea. There was a little

confusion about what the responsibilities were. And there were ofcers that really

didn’t know the [MCAT teams] were out there.”

Similar statements were made regarding other community treatment providers. It was suggested that prior to

launch, key stakeholders “should have met with other hospitals before the MCAT program started because they

needtoknowwhoweareandwhywe’rebringinginpatients”andthat“mostpeopledon’tevenknowwhat

MCAT is so I don’t even think that most [doctors] would realize that their patient was brought by MCAT to the

emergencydepartment.”

Therewasalsoaperceivedneedtobetter“market”MCATtothepublicinordertodifferentiatethisprogram

from other initiatives in the East District; one stakeholder explained that other initiatives imbedded in East District

had misconceptions about what MCAT would and wouldn’t do. It is important to involve other actors in the area;

as an MCAT stakeholder advises:

“I would want other agencies to know that you have to be out there selling the

program. When I say out there, I mean other stakeholders in the community and you

have to nd outside partners...It’s not just a police program or a city program or an

EMS program or a clinician program. It is a collaborative approach and I think you

have to have people who understand that.”

By coordinating with other programs and initiatives aimed at helping similar populations, future implementation

efforts might better ensure all stakeholders are aware of the roles of one another. Additionally, it is important to

disseminate coordinated messages to the community and patients receiving MCAT assistance to avoid confusion

about roles and capabilities.

Outpatient Resources

Thedifcultypresentedby alackofoutpatient servicesforpopulationsservedbyMCATsurfacedmultiple

times throughout researcher’s review of both this data and data from previous studies. One MCAT stakeholder

conveyed:

“This is the biggest fear for me; you do all of this work on the front end, but there

are no real services on the back end, so these people aren’t getting the help, because

there are not enough beds or there are not enough mental health professionals that

will work with them, or they don’t have any insurance.”

Addressing the needs of the populations with behavioral health and substance use issues goes beyond responding

to acute emergencies and performing follow up. MCAT team members can provide resources or transport

patients to a hospital or other crisis center, but this does not guarantee the availability of necessary treatment

for people. An MCAT stakeholder suggested that “the city was under the impression that there are places to take

people;therearenot.”Futureimplementationsshouldrstconsiderexpandingtreatmentoptions,

10

“If we are talking about launching this in a thoughtful way in other places, then

making sure that treatment resources are available [is crucial]. You sort of have

to work backwards: if you’re going to go out and nd people who need help, you

probably want to have that help available.”

This was an especially prominent issue in terms of substance abuse treatment. In the midst of an opioid crisis in

Indianapolis, MCAT members noted that they “really don’t have anywhere to send people who need help with

heroinaddiction.”Giventheavailableresources,MCATmemberslamentedthatcrisisresponseswere“goingto

havetocontinuewiththeemergencydepartmentandthejail”butexpressedadesireto“workwithprovidersto

buildrelationshipsandndprovidersthatarewillingtoparticipatewithaclientelethatdoesnothavethebest

resourcesbutwhoaremostinneedoftreatment.”

Limited treatment resources can be a barrier to long-term health for patients, and can also lead to frustration

and burn-out from staff committed to serving people experiencing behavioral health and substance use issues.

For example, as one MCAT member noted, “people come out of [the hospital] not making changes because they

werejustgivenapamphlet,notservices”whileanotherstakeholdersuggestedthat,

“A lot of time and effort and money is being spent on innovative programs when

really probably a lot more time and effort and energy should be spent building the

capacity of our behavioral health system to take care of people.”

Addressing these issues requires bolstering a broader system of behavioral health care beyond the purview of

MCAT,follow-upunits,emergencydepartmentsandrst-responders.

Role Conict and Stigma

Switchingfromatraditionalroletoaspecialunit,particularlyforpoliceofcersandparamedics,wasidentied

asadifcultprocess.SomeMCATmembersexperiencedpersonaldiscomfortwithnewrolesandweremetwith

negative feedback from within their respective agencies, similar to team members in other types of co-response

teamsstudiedintheliterature.Forexample,oneMCATofcersuggestedthat“[Otherofcerssay]we’rejokes

now;wearen’ttherealpolice.”Thistypeofcriticismwasalsoheardfromotherrstresponders;membersstated

that“reghtershavebeenparticularlyresistanttounderstandwhatwedo”andthat“everyambulanceI’verun

intothinkswearetheretodotheirlegwork.”

SomeMCATteammembershaddifcultyadjustingtothenewidentityassociatedwiththeirspecialunitroles.

OnewaythismanifestedwasconcernabouttheMCATuniforms;asoneofcerstated,“thereishonorinyour

uniformandthisMCATuniformisahalfway-policeofceruniform.”

Leadership was aware that certain aspects of a new role as well as riffs with non-special unit personnel might

contribute to team member dissatisfaction or frustration. As one key stakeholder stated,

“One of the most difcult things is coming out of what they are normally doing...

they have all been on the street... so I think that’s an adjustment for them. Any time

law enforcement leaves the rst position (which is street ofcer position and goes to

investigation or something else) it’s often difcult to make that transition.”

11

Leadership also noted that:

“There was a lot of pressure and push back, just culturally within the organization.

Oh, why are you going to a special unit? What are you even going to be doing?

And [ofcers] couldn’t really answer that... It takes a certain type of ofcer with a lot

of self-condence and an open mind.”

Having buy-in from MCAT members is not only crucial for the success of the current program, but also something

to be considered in future implementation efforts. For example, one MCAT team member stated, “I have over 20

yearsofseasonedexperience,IfeellikeIambeingwastedinthatvan.”Effortstocarefullyselect,retainand

motivate team members are important to long-term program success.

FACILITATORS TO PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION

Initial Citywide Collaboration and Buy-In

As evidenced in the literature, the success of an emergency response team like the MCAT requires buy-in from

many people and agencies who do not necessarily interact with this level of coordination ordinarily. Fortunately,

Indianapolis has multiple years of collaboration between mental health providers and IMPD, has incorporated

CIT training for many ofcers, and has the full support of the Mayor’s Ofce for the MCAT program. For

example, one respondent noted “this is a collaborative approach and you have to have people who understand

thatandcanworkinacollaborativeenvironment.”Anotherstakeholderestablished,

“Even before [MCAT] we had a good relationship with medical services here, a good

relationship with Eskenazi, and a good relationship with mental health workers. So,

from the top down there had been a lot of history and a lot of associations with

individuals who have thought the same way.”

This level of citywide effort in developing multi-agency responses to behavioral health and substance use issues

coupled with dedicated buy-in from agency leadership for development of the MCAT program facilitated a

relatively cooperative implementation and opened avenues for future coordination. Respondents especially noted

supportfromtheMayor’sOfce,asitprovidedaplatformforresourcenegotiationandagencyaccountability.

As one MCAT stakeholder said, “there is going to be push-back any time there is change; having the support

fromthetopiscrucial.”Anotherrespondentassertedthat:

“It has to start from the top down because this is an ask from everybody... there has

to be a return on investment for everybody involved that’s not money...So we have

all of these different moving parts, and when you put the leadership together in a

collaborative way, and these folks all want to solve the same problem, we can sort of

understand, ‘ok I can lose over here if I win over here.”

Programs like MCAT can take advantage of already-existing synergies between agencies, and further combining

efforts can open doors for future collaboration by breaking down communication and coordination barriers. This

allows leadership to leave their agency silos to address common issues in concert. As one respondent expressed,

“MCAT helps with pushing uncomfortable change and having collaboration. It has also helped us look at the

otherwayswecanworktogethertomakeadditionalchanges[tothesystem].”

12

Information Sharing

One of the most salient facilitators of implementation noted by participants in the current and previous studies

wastheabilitytoshareinformationwithinlegalpurview.MCATunitsbenetfromthecombinationofpatient

information from three different entities that serve the same populations. This triangulation of informational

resourcesresultsinagreaterabilitytoaddressaspecicpatientinthemomentofcrisisandlinkorre-engage

them with treatment services. Combining information also helps to identify the patterns and needs of “frequent

yers” of city emergency resources. This facilitator was expressed by multiple stakeholders throughout the

qualitative data. For example:

“It has enabled us to have a deeper understanding of the city enterprise as a whole...

We are able to really have a clear picture of [a patient’s] process through the

system. And we are able to see where we have very distinct weaknesses in our system.

Whether that’s lack of services, lack of support, a lack of communication...”

“There is a Midtown clinician that...is able to link [a patient] back to their treatment

team via our own medical record and communicate that this person is having a

problem, and then you can go in and see [if] this person is getting a follow up from

the treatment team the next day, versus kind of just letting them go.”

Duringeldobservation,researchersrecognizedtheusefulnessofcombiningtheEskenaziandIMPDinformation

systemstoidentifythecorrectaddressofaspecicpatient.OneMCATteammemberstated,“Ilovethatthe

clinician can get on the computer and look up any existing mental health issues that a person has; I’ve never

seenthatbefore.”Stakeholdersrealizedthat,“Combiningthesystemsandsoftwareofthreeagenciescreates

apowerfultool.”

Uponrespondingtoanemergencyscene,ofcersandclinicianscancomparecriminaljusticeandhealthcare

records on their laptops within legal parameters to better prepare the team to respond to a particular patient.

This triangulation can help teams anticipate potential hazards and also allows them to reconnect patients with

treatment services they received in the past when applicable. As one MCAT stakeholder stated,

“We can look at [a situation] from multiple different angles. We can do searches...

We typically try to do our homework when we go out and see somebody, especially

if we have a name ahead of time. Or if it’s on the back end we will look at it after

we get back to the ofce to try to see what has happened with this person in the past.

The police ofcer will go and look at what their record is. Our clinician can look to

see if they are in the Midtown system to see if they have been there before for some

other mental health treatment... and then from the medical side we can see...how many

times they have called in the past few years and now we are putting together a better

picture on things.”

As noted, combining multiple agencies to address emergencies had the unintended consequence of identifying

someofthefrequentyersofcityresources.Whilethesepeoplemayhavebeencontactedindividuallybythe

three agencies involved prior to MCAT, coordinated efforts to identify, record information and support those

individualswerenotasefcientastheycanbethroughMCAT.

13

Team Building

One of the most useful aspects of initial training was the ability for MCAT team members to learn about one

another, adopt useful skills from one another and build relationships. Team members were introduced to the

philosophies, language and procedures of the other agencies involved with MCAT during an almost two-month

training. As one MCAT stakeholder suggested, “It was apparent that each different agency needed to be a little

moreawareoftheotheragenciesinordertoworkmorecloselytogether.”Teammembersfoundthat,“Thebest

part[abouttraining]waslearningoneanother’srole”and“ThetrainingbroughtthisunittogetherandIthinkall

theteamsarefunctioningprettygood.”TheMCATmembersalsonotedthatbeingabletoselecttheirteamswas

a facilitator to program implementation, suggesting that “If we were assigned teams, we may not have been as

successful,butwegottopickourteamsandgetalongbetterforit.”

Researchers observed collegiality among the team members they accompanied during ride-along observations.

The clinician expressed observations of subtle changes in EMS team members’ interaction with persons with

behavioral health issues as a result of collaborating with other MCAT members. This change was also self-

identiedbyIMPDandIEMSmembersoftheMCAT,statingthattheir“mindsetwaschangedbecauseofthe

training.”

TheCCJRsurveyofIMPDEastDistrictofcersyielded63responseswhichisapproximatelya45%response

rate.Respondentswereanaverageageof39(SD=10.49,Range:18to65)andprimarilymale(76%)and

Caucasian(75%).Slightlymorethanhalfofrespondentshadatleastafour-yearcollegedegree(56%)and

had been in law enforcement for an average 13.10 years (SD = 10.39, Range: 1 to 40) with most currently

employedaspatrolofcers(78%).

CCJRresearchersrstaskedrespondentstoevaluatetheirlevelofknowledgeandcontactwiththeMCATteams.

LeadershipmadeeffortstointroducetheMCATteamstoEastDistrictofcersduringroll-call,shortmeetings

thatoccurbeforeeveryshift.However,thismethoddidnotreachallofcersaccordingtothesurveyas29%

of ofcers indicated that theywerenot formally introducedto theMCATprogrambeforeitslaunch. Next,

researchers looked at perceptions regarding the roles and expectations of the MCAT unit before and after

launch.

AsshowninExhibit1,57%statedthatrolesandresponsibilitiessurroundingtheMCATunitweresomewhatclear

orextremelyclearpriortolaunchandatthetimeofthesurvey(mid-lateNovember)84%saidtheroleswere

somewhat or extremely clear. This increased trend in role clarity is likely attributable to the fact that a high

proportionofrespondents,87%,reportedhavingbeenonthesceneofanemergencycallwiththeMCAT.The

surveyalsoallowedforopportunitiesforofcerstoexpress,throughopen-endedquestions,whatwouldmake

theMCATmoreusefultothemasofcersand6respondentsmentionedadesireforclaricationonMCATroles

andthattheseexpectationsbeconsistentbetweenMCATteams.Ofcerssaid,“itwouldbehelpfultoknow

exactlywhatMCATcanandcan’tdo”and“Ijustwantaclearerunderstandingofthesituationstheywill/will

notrespondto.”

IMPD EAST DISTRICT OFFICER SURVEY

14

Researchers also looked at perceptions of MCAT emergency responses. Most survey participants reported

thattheyhadspecicallyrequestedMCATassistanceonascene(83%)and79%reportedthattheMCATunit

arrivesallormostofthetimewhenrequested.DiscussionwithMCATteammembersandeld-observationswith

one team revealed a few reasons why the MCAT does not always arrive when requested. Teams are either

unavailable due to being at the scene of another crisis or cannot arrive fast enough due to their limited ability

totravelquicklyacrossthedistrict.ThesurveyalsorevealedthatEastDistrictofcerswouldlikefortheMCAT

to be more available: in an open-ended question, 17 respondents said the MCAT would be more useful if it was

moreavailable.Oneofcersuggests,“Getmoreofthemworkingatonetime...maybetwoorthreewouldhelp.

Therehavebeenmultipletimeswehaveaskedfor[assistance]wheretheywerealreadyoutonsomething.”

EXHIBIT 1. Clarity of Roles and Expectations of the MCAT Unit

EastDistrictOfcerPerceptions

27%

16%

57%

13%

3%

84%

Unclea r Neu tra l Clear

Percent of Officer Survey Responses

Prior to Launch Now

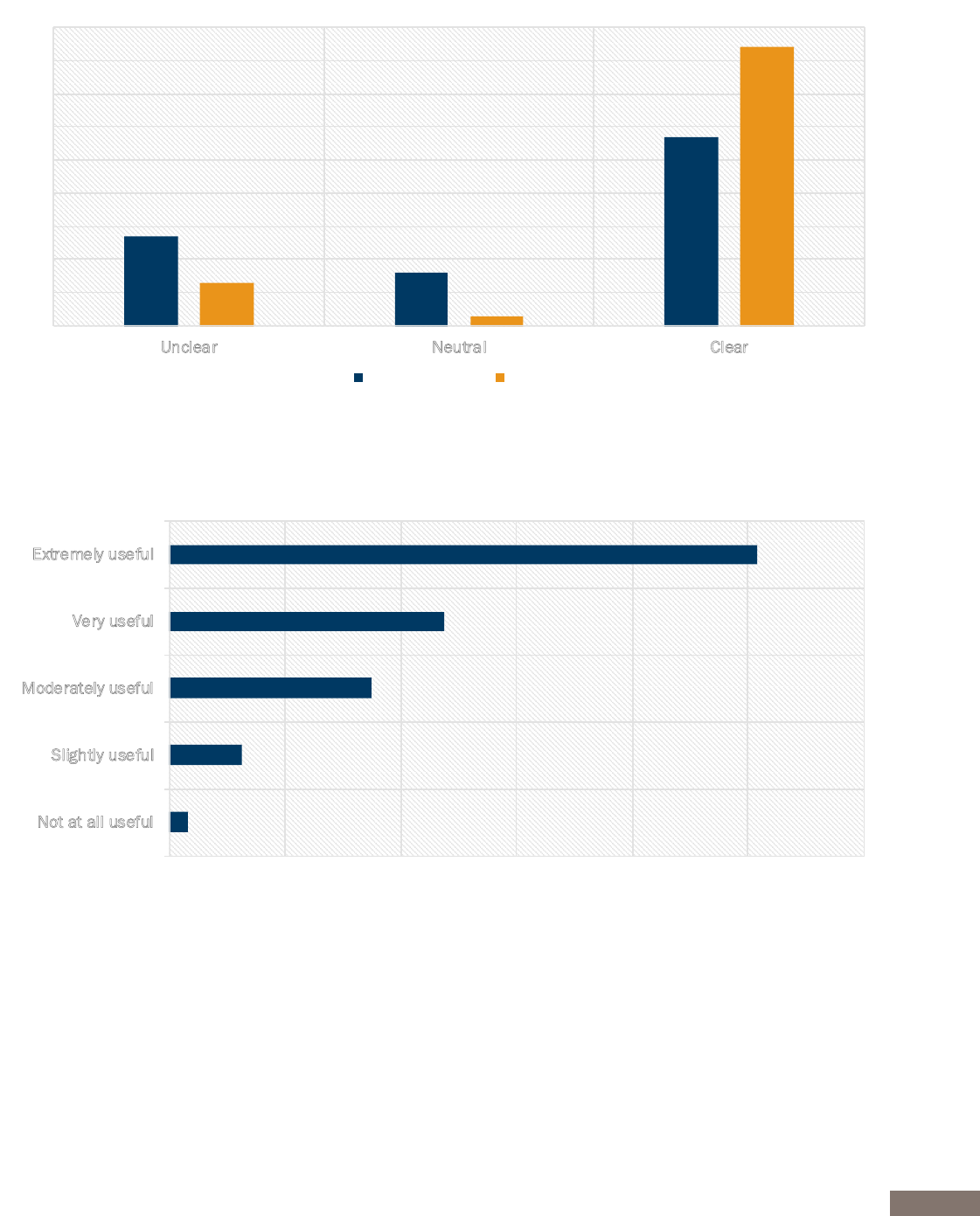

EXHIBIT 2. Perceptions of MCAT Usefulness

EastDistrictOfcerPerceptions

2%

6%

18%

24%

51%

Not at all useful

Slightly useful

Moderately useful

Very useful

Extremely useful

27%

16%

57%

13%

3%

84%

Unclea r Neu tra l Clear

Percent of Officer Survey Responses

Prior to Launch Now

15

Finally,researcherslookedatperceptionsofMCATusefulness.Overall,EastDistrictofcersndthattheMCAT

isaveryusefulresourcebecauseitallowsofcerstoreturntodutymorequicklyandbecausetheteamprovides

theabilitytobetteraddressmentalhealthcrises.AmajorityofofcersbelievetheEastDistrictisbetterat

responding to mental health crises because of the MCAT. As shown in Exhibit 2, respondents overwhelmingly

ratedtheMCATunitasveryorextremelyusefultothemasofcers(75%).Ofcerrespondentswereasked

toreportthereasonsforwhichtheyndtheMCATtobeuseful.Respondentsweremostlikelytoendorsethe

MCATteamasbeingusefulbecausetheyallowotherofcerstoreturntodutymorequickly(86%);theunique

combinationofanIEMS,IMPD,andclinician(73%);mentalhealthexpertise(64%);abilitytocompletefollow-

up(52%);andadditionalequipmentandresources(49%).Incontrast,respondentswerelesslikelytoviewthe

MCATasusefulforitsabilitytohandlenon-emergencycalls(44%)orprovidesubstanceabuseexpertise(35%).

FocusgroupdatawithMCATmemberssuggeststhatpartofthereasonofcersintheEastDistrictmightnot

perceive the unit as useful in terms of substance abuse is because on the scene of overdose they don’t have the

abilitytoarriveintimetoreviveapersonbeforeotherrst-respondersdoso,andanoverdosepatientisoften

not in a state of mind to engage in discussion about treatment in the moment.

In evaluating the improved ability of the East district to address mental health and substance abuse issues, a

greater proportion of respondents rated East District having a better response to mental health issues due to the

presenceofMCAT(79%)relativetosubstanceuseissues(49%).Aconsiderable89%ofrespondentsbelieved

theMCATunitmetorexceededexpectationssetpriortoitslaunch.Oneofcerstates,“IhonestlythinktheMCAT

crewisdoingaphenomenaljob.”Thisisalsoevidentinthefactthat33%ofofcersindicatedbeinginterested

inservingintheofcerroleontheMCAT.

16

In examining the data on MCAT responses, researchers looked at the characteristics of the people to whom

MCATrespondedandthenproceededtolookatresponseresultschronologically:rstlookingatthereasonfor

the response, then what happened on the scene of a response, and then the outcome of the response. Following

this, researchers examined repeat encounters and differences by teams.

The data used in this analysis come from all MCAT responses that occurred between August 1, 2017 and

December 9, 2017 that were recorded by MCAT team members. During these 19 weeks, there were a total

of 566 responses at approximately 4.4 runs per day. Every day during the study period there was at least 1

response and a day high number of 11 responses. It is also important to note that the 566 MCAT responses

occurredamong488uniqueindividualsas11%oftheresponseswererepeatencounters.

CLIENT DEMOGRAPHICS

Exhibit 3 displays the demographic characteristics among the 488 individuals that MCAT responded to during

thestudyperiod.Morethanhalf(58%)oftheresponseencounterswerewithmalesandmorethanhalf(55%)

wereCaucasian,41%wereBlackorAfricanAmerican,and3%Hispanic.Theaverageageofindividualswith

an MCAT encounter was 38 years and ranged from 10 years old to 90 years old.

QUANTITATIVE DATA ON MCAT RESPONSES

EXHIBIT 3. Demographic Characteristics of MCAT Response Cases

Race/Ethnicity

55%

41%

3%

1%

White Black Hispa nic Other

55%

41%

3%

1%

White

Black

Hispa nic

Other

Female

42%

Male

58%

Gender

N=286 N=210

Average Age

37.9 years old

Standard Deviation: 15.3

17

REASON FOR RESPONSE

MCAT team members were asked to record whether they self-dispatched to a given crisis scene or if another

agencyrequestedtheirresponse.Here,researchersfoundthatnearlytwo-thirds(63%)ofresponseswerethe

resultofMCATself-respondingandtheotherone-third(35%)werefromIMPDrequests;therewere8responses

requested from EMS, 5 from other agencies, and 16 response sources not recorded. MCAT also recorded what

the primary crises were and were able to select all responses that applied from six categories: (1) Suicide or

self-harm attempt or threat (2) Other mental health issues, (3) Overdose or other substance abuse problem, (4)

Domestic violence, (5) Physical health issue, (6) and Gravely disabled. Exhibit 4 shows the frequency that each of

thecategorieswererecordedaswellastheinstancesinwhichonlyonecategorywasrecorded:at59%,mental

healthconcernswerethemostcommonprimaryreasonforresponseandwastheonlycrisistypein37%of

responses. The second most frequent response reason was an overdose or other substance abuse problem which

wasindicated35.4%ofthetimeandwastheonlyreasonforaresponsein23%oftheencounters.Onlyslightly

lessthansubstanceabusewasself-harmorthreatofsuicidewhichwasindicatedin34%oftheencountersand

theonlyresponsereasonindicatedin18%oftheencounters.MCATresponsesfordomesticviolence,physical

health,orgravelydisabledwerelesscommonandtogetherwererecordedin10%ofencountersandeach

recordedastheonlyreasonforaresponseinlessthan2%ofencounters.

Another important point to examine with the MCAT data is whether responses or encounters changed over

time. As shown in Exhibit 5, researchers display the top three kinds of responses (mental health, self-harm,

andsubstanceabuse)duringtherstfourmonthsandfoundsomeuctuationovertimeinthetypesofMCAT

responses. While mental health related calls have remained the most frequent response, the number of self-

harm related responses has increased from 27 to 41. The number of substance abuse related responses started

EXHIBIT 4. Reasons for MCAT Response

Primary Crisis

3%

4%

4%

34%

35%

59%

2%

2%

1%

18%

23%

37%

Domestic violence

Physical Health

Gravely Disabled

Self-H a rm

Overdose or

Substance Abuse

Menta l Hea lth

Percent of runs in which crisis type was indicated

Crisis Type

Only Indication Any Indication

18

high at 50 but decreased during September and October to 29 and 30 respectively and increased to 49 in

November. This is a very limited follow-up period and additional data are needed to further examine these

trends.Thisuctuationmaybeduetothenumberofemergencycallsthatcomethroughforeachcrisistype,the

availability of MCAT to respond, response decisions of MCAT teams, or a combination of these factors.

SCENE OF AN MCAT RESPONSE

When MCATresponded to a crisis scene there were often other emergencyor rst response units already

present:inonly9%ofresponseswasMCATtheonlyunitresponding.IMPDwasalsoonthescenefor85%

ofresponses,EMSat58%ofresponses,andIFDat18%.BothEMSandIMPDwereatthesceneof52%of

responsesandIMPD,EMS,andIFDat16%ofresponses.While generally not the only unit on the scene, in two-

thirds (66%) of encounters, MCAT was able to relieve other emergency or rst response units from the scene.

AmongthoseencounterswhereMCATwasabletorelieveotherunits,63%ofthetimeitwasoneunit(EMS,

IMPD,orIFD),31%ofthetimeitwastwounits,and6%ofthetimeitwasallthreeunits.TheMCATalsoreported

additionalhazardspresentatthescenefor16%oftheencounterswiththemostcommonhazardreportedas

violentbehaviortowardothersbutonlyoccurredin7%ofencounters.Thenextmostcommonhazardreported

wasthepresenceofweaponswhichoccurredin3%ofencounters.

InlookingatthetimespentonthescenethemajorityofMCATencounterswerecompletedinunder90minutes

(88%) with 62% taking an hour or less. For those encounters that took longer to complete,the MCAT was

signicantly more likely have relieved other emergency or rst response units. For example, among those

encountersthatwereoveranhour,80%ofthetimeotheragencieswerereportedashavingbeenrelievedfrom

the scene.

EXHIBIT 5. MCAT Response Types over Time

27

35

48

41

64

69

55

73

50

29

30

49

August September October November

Nu mber of MCAT Runs

Self H a rm Menta l Hea lth Susbtance Abuse

19

MCAT RESPONSE OUTCOMES

OneofthemaingoalsoftheMCATteamistodivertpersonsawayfromjailorincarcerationwhenpossibleand

appropriate, and transport them into needed treatment or services. Following an MCAT encounter, two-thirds of

patients(65%)weretransportedsomewhere,themajorityofwhom(87%)weretransportedtoahospital(33%

weretransportedtoEskenaziHospital).Thismeansthat56%ofallMCATrunsresultedintransportingapersonto

ahospital.In25%ofMCATresponsestherewasanimmediatedetentiondecisionandinnearlyallofthesecases

the MCAT team provided transportation. Exhibit 6 shows the location and outcome of other transports provided by

MCAT.7%ofcrisestowhichMCATrespondedresultedinanarrestandamongthesearrests74%ofthetimeitwas

anIMPDofceralreadyonthescenethatinitiatedanarrest,ratherthananMCATofcer.Infact,MCATonlydirectly

transportedsomeonetojail9timesduringthestudyperiod,orotherwisestated,inlessthan2%ofallencounters.

Therewasnostatisticallysignicantvariationinindividualcharacteristicsorresponsetypeinthelikelihoodtoarrest.

REPEAT ENCOUNTERS

AlargemajorityofindividualsreceivedonlyoneMCATresponse;however,11%oftheoverallsamplereceived

two or more MCAT responses. These repeat encounters involved independent crises and resulting MCAT responses,

they were not follow-ups from a previous response. The average number of responses provided to this sub-

populationrangedfrom2to7encountersandtheaverageamountoftimebetweenindividuals’rstandlast

MCAT encounter was 17 days (M=27.84, SD=27.84). To explore the possibility that individual characteristics

and encounter circumstances can distinguish individuals who receive one MCAT response from individuals who

receivetwoormoreMCATresponses,comparisonsaremadebetweenindividuals’rstMCATresponse.Therst

response was purposely selected as the comparison point as this encounter sets the foundation for sequential

EXHIBIT 6. MCAT Response Outcomes

33%

54%

4%

4%

2%

2%

2%

Eske na z i

Hospit al

Ot her

Hospit al

Residence Reuben

Center

Shelter Other

Crisis

Center

Jail

Percent of MCAT runs resulting in transport

L oc ation

35%

65%

Not Transported

Transported

Did MCAT transport

person in crisis?

When MCAT transported someone,

where were they taken?

56% of all MCAT runs resulted in

transport to a hospital

20

activities. Three factors provide some insights. First, individuals who receive two or more MCAT responses were

more likely to have“gravely disabled” as the primary crisis type with no other crisis classications in their

initial response. Second, a larger proportion of individuals who experienced repeat encounters with MCAT

wererecordedashavingmentalhealthissues(59%)asaprimarycrisisthanindividualswhoreceivedasingle

MCATresponse(45%).Therewerenodifferencesbetweenrepeatandsoleencountersacrosstheremaining

combinations of response categories. Third, a smaller proportion of individuals who received more than one

MCATresponseweretransported(52%)inrelationtoindividualswhoreceivedoneresponse(66%).When

comparing the locations to which individuals are transported, there are no differences between the locations

to which they are delivered that would signal the need for subsequent encounters. In combination, this third

factor provides evidence that it is the decision to transport and not the location to which one is transported that

inuenceswhetheranindividualreceivesarepeatencounter.

Beyond these indicators, there were no other statistically dependable characteristics or circumstances that

enabled an ability to differentiate repeat and sole MCAT encounters. The responding MCAT unit, presence of

emergencyorrstresponseunitsatthescene,existenceofhazardsduringtheencounter,timingoftheencounter,

andactions takenduring the rst encounter did not help to identifyindividuals who wouldreceivemultiple

responses.

DIFFERENCES BY MCAT UNITS

InordertounderstandtheimpactofaspecicMCATunitonresponses,CCJRresearchersexamineddifferences

across the four unique units, referred to hereafter as Unit A, Unit B, Unit C, and Unit D. Researchers also looked

at variation between day and night shifts with Unit A and Unit B as the day shifts and Unit C and Unit D as the

nightshifts.Exhibit8displaysthestatisticallysignicantdifferencesresearchersfoundacrossthesefourunits.

Forexample,asillustratedinExhibit8,UnitAandUnitBweresignicantlymorelikelytoself-dispatchtoacall

whereas Unit C and Unit D were more likely to have been dispatched by IMPD. In terms of the type of calls,

researchers examined those cases where only one type of crisis type was indicated and found that Unit A was

more likely than the other units to respond to a self-harm and mental health related crisis calls but least likely

torespondtoasubstanceabusecall.AsshowninExhibit8,overone-quarter(26%)ofUnitD’sresponseswere

exclusivelysubstanceabuserelatedwhichwassignicantlyhigherthantheotherunits.

EXHIBIT 7. MCAT Repeat versus Single Encounters: Comparison of Transport & Crisis Type

5%

59%

52%

1%

45%

66%

Gravely Disabled

(Only Indicatio n)

Menta l Hea lth

(Only Indicatio n)

Transported

Single Encounters Repeat Encounters

21

Intermsofwhathappenedatthescene,therewerenosignicantdifferencesinthelikelihoodtotransportor

arrest.UnitBwasalsosignicantlymorelikelytorelieveotherrstresponseunitsandalsohadthequickest

responsetimewith23%ofresponseslasting30minutesorlessand72%lastinglessthanhour.Thisrateof

expeditious response was also shared by Unit A. Finally, Unit B was least likely to have had repeat responses.

Researchers also examined differences between shifts that occurred at day and at night and between those

instances where there was a full MCAT team available and those responses where a member of the team was

missing. While there was some variation in encounter characteristics and circumstances by shift and by complete

or incomplete MCAT teams, much of the differences were between units rather than shifts or complete versus

incomplete teams. Moreover, given the data available at this time, researchers cannot say that any of these

congurationswerebetterorworsebutsimplywanttonotethevariabilityinresponsetypesandtimespenton

the scene.

EXHIBIT 8. Variation by MCAT Units

UNIT A UNIT B UNIT C UNIT D

Response Request

MCAT Self Dispatch 51% 72% 66% 59%

IMPD Request 48% 27% 32% 37%

Reason for Response (mutually exclusive)

Self Harm 26% 50% 14% 19%

Mental Health 40% 33% 30% 24%

Overdose or Substance Abuse 12% 15% 18% 26%

Units Relieved

IMPD 41% 67% 58% 65%

IEMS 21% 36% 17% 27%

Any Unit 51% 75% 60% 72%

Response Scene and Outcome

Repeat Encounter 30% 23% 30% 18%

Immediate Detention 17% 36% 17% 26%

Time at Scene

Under 30 Minutes 23% 23% 15% 10%

Under 60 Minutes 69% 72% 48% 59%

22

After a review of the academic literature and a detailed description of the Indianapolis MCAT pilot program, this

studyidentiedanumberofimportantbarriersandfacilitatorstothepilotprogram’simplementation.Interms

of barriers, much like the academic literature on co-response teams, researchers found that ambiguity in terms

ofpoliciesandprocedureswasidentiedasabarrierandmanifesteditselfinanumberofwaysthroughout

theevaluation.Therewasdifcultywithexternalcoordination,inpartbecausetheMCATunitsareunableto

clearlyexpressthepurviewoftheprogramtootherrstresponseandcommunityagencies.Thisbarrierwas

alsoevidentintheEastDistrictsurvey,wherenearlyhalfofofcers(42.8%)statedthattheprogramwasnot

made clear to them prior to launch. This survey suggests that as the MCAT unit became a regular part of the

districtofcers’interactions,theycametobetterunderstanditsroles;however,it’sunclearifthecrystallizationof

these roles actually occurred among the MCAT units themselves. The biggest indicator of a lack of policies and

procedures was in the analysis of the quantitative data where researchers found MCAT units were responding

to different kinds of calls for service. Given the available data and the time of that the pilot program has

been in existence, researchers are not in a position to say which units were operating better or worse; rather,

researcherswouldspeculatethatthisvariationisduetothelackofdelityinprogramimplementationwhich

might be addressed by establishing clear guidelines as part of an MCAT policies and procedures document.

Strong support from city ofcials and key stakeholders was identied as a facilitator towards program

implementation.However,thissupportmightbecodiedandextendedbycreatinganadvisorygroupand/or

program coordinator for the MCAT units. An advisory group and/or program coordinator could communicate

what the goals and guidelines of the MCAT are to other key community stakeholders and agencies, improving

externalcoordination,whichwasidentiedasabarriertoprogramimplementation.Theadvisorygroupor

coordinator could also regularly evaluate the consistency of MCAT responses amongst teams and serve as a

liaisonbetweenteammembersandcityofcialstocentralizecommunication.

Team building was also identied as a facilitator to MCAT implementation. Specically, researchers found

that MCAT members felt training led to a sense of unity among team members. Unfortunately, feelings of

ostracizationfromfellowrstresponderswerealsopresent,asseveralMCATmembersnotedfeelingdiscomfort

in their new roles as a result. However, these feelings are not entirely consistent with the survey in which East

DistrictofcerswereoverwhelminglysupportiveoftheMCATpilotandfeltthatitmetorexceededexpectations.

It is possible that the negative stigma expressed towards MCAT members was an impactful, but relatively rare

event,orwassomethingthatoccurredonlyinitiallyinthepilot.Itisalsoworthnotingthatone-thirdofofcers

surveyedintheEastDistrictwereinterestedinservingasanMCATofcer,whichsuggestsapotentialpoolof

futureMCATofcerteammembers.

ThemostsignicantbarriertosuccessfulimplementationofMCATasawaytodivertpeoplefromthecriminal

justicesystemandintotreatmentserviceswasalackofcommunitytreatmentoptions.Thiswascommonlycited

as source of frustration by the MCAT members, leadership, and the community stakeholders in this study, as well

as participants in previous studies of similar co-response teams. Further research may attempt to follow up with

people who interacted with MCAT to understand the extent of their post-MCAT treatment.

By and large, the most salient facilitator to MCAT implementation was the ability share information in real time

between agencies. MCAT members from IMPD and IEMS regularly noted the advantages to having additional

CONCLUSIONS & FUTURE RESEARCH

23

informationonpersons.Thisinformationallowedthemtolocateindividualsmoreefcientlyandbetterunderstand

uniquetreatmentneeds.Giventheimportanceofthisfacilitator,itisworthexploringhowotherIMPDofcers,

who are not a part a specialized unit, might acquire access to this kind of information. Moreover, it would be

helpfultondawayofacquiringsimilarinformationfromprovidersotherthanMidtown.

Finally, our analysis of preliminary quantitative data from MCAT responses suggests that the program is meeting

itsprimarygoalofdivertingpersonsawayfromjail.Forexample,twothirdsofMCATresponsesresultedin

atransport;nearly90%ofthesepersonsweretransportedtoahospitalorothertreatmentfacilitywhileless

than2%weretransportedtojail.Futurecomparativestudiescandeterminewhetherthisdifferssignicantly

fromothersimilarcrisissituationswhereMCATisnotpresent.Whilethejaildiversiontrendispromising,this

ndingalsoraisesquestionsabouttheaimofMCATtoreducetheutilizationofemergencyservicesandseek

alternatives to hospitalizations given the high rate of transport to hospitals.

Alsonoteworthyisthatintwo-thirdsofallMCATresponsestheywereabletorelieveoneormoreotherrst

response units thereby improving overall emergencysystem efciency by freeing them to respond to other

calls for service. As noted above, there was variability across MCAT units in the kinds of calls they responded

to; however, at this time, researchers cannot determine whether these are meaningful differences that will be

related to outcomes or due to a lack of clear policy and procedure guidelines for MCAT units.

AlsoofnoteweretherepeatMCATencounters.Astheirtimeintheeldincreased,MCATteamscametodiscover

personswhowere“frequentyers”andinsomecasestheMCATmembersreporthavingbecometheprimary

response unit for these persons. While this led to mild frustration among MCAT members, it is also important to

notethatthesefrequentyersweremorelikelytobedisabledandmentallyillthanthepopulationofpeople

involved in only a single MCAT encounter. It might be innovative to accept that, given the nature of the program,

MCAT units are likely to identify these cases and supply them with resources or provide additional interventions.

ThisstudyrepresentsaverybriefsnapshotoftherstvemonthsoftheMCATprogram.Muchmoreresearch

is necessary to fully understand whether the MCAT program is effective in having a long term impact on the

communities it serves. Generally speaking researchers suggest at least three additional types of studies need

to occur to examine program effectiveness. First, data from the MCAT responses need to be linked to other

availabledatasources.Indoingso,researcherswillbeabletolookatchangesincriminaljusticeinvolvement,

the use of IEMS, and potentially treatment engagement. Second, the MCAT responses need to be compared

to similar emergency calls for which MCAT is not present. This would allow researchers to determine whether

the rate of arrest for the MCAT is truly lower than if an MCAT had not responded. Findings in the literature

havesuggestedthatthe arrestrateofPMIissomewherebetween2% and19%,dependingontheofcer

training, the availability of special units to address mental health crises and other factors (Borum and Franz,

2010; Reuland et. al. 2009). Finally, researchers need to better understand the perceptions and experiences

of individuals who are consumers of MCAT services. These individuals could elaborate on how their experiences

with MCAT differ from previous calls for service, whether their experiences had an impact on impressions of

IMPD, IEMS or Midtown, and whether the MCAT response had any short-term or long-term effects on behavioral

health changes and treatment linkage.

24

Adelman, J. (2003). Study in blue and grey. Police interventions with people with mental illness: A review of

challenges. Vancouver: Canadian Mental Health Association, BC Division.

Baess, E.P. (2005). Review of pairing police with mental health outreach services. Unpublished report, Vancouver

Island Health Authority.

Compton, M. T., Bahora, M., Watson, A. C., & Oliva, J. R. (2008). A comprehensive review of extant research on

crisis intervention team (CIT) programs. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law, 36, 47-55.

Deane M, Steadman H, Borum R, Veysey B, Morrissey J. (1999). Emerging partnerships between mental health

and law enforcement. Psychiatric Services, 50(1), 99–101.

Dupont, R., Cochran, S., & Pillsbury, S. (2007). Crisis intervention team core elements. Unpublished report,

University of Memphis.

Greene J.C., Caracelli, V.J., & Graham, W.F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method

evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255-74.

Hartford, K., Carey, R., & Mendonca, J. (2006). Pre-arrest diversion of people with mental illness: Literature

review and international survey. Behavioral Sciences & The Law, 24(6), 845-856.

Hay, T. (2015). Mental health treatment for delinquent juveniles: A new model for law enforcement-based

diversion. Appalachian Journal of Law, 14(2), 151-168.

Kirst, M., Francombe Pridham, K., Narrandes, R., Matheson, F., Young, L., Niedra, K., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2015).

Examining implementation of mobile, police-mental health crisis intervention teams in a large urban center.

Journal of Mental Health, 24(6), 369-374.

Lamb,H.R.&Grant,R.W.(1982).Thementally-illinanurbancountyjail.Archives of General Psychiatry 39(1),

17-22.

McQuaid,R.(2015,August27).MarionCo.SheriffrunsthelargestmentalillnessfacilityinIndianapolis:thejail.

Retrieved from http://fox59.com/2015/08/27/marion-co-sheriff-runs-the-largest-mental-illness-facility-

in-indianapolis-the-jail/

McQuaid, R. (2017, October 19). Mother alleges son with mental disabilities was denied meds inside Marion

County Jail. Retrieved from http://fox59.com/2017/10/19/mother-alleges-son-with-mental-disabilities-

was-denied-meds-inside-marion-county-jail/

Muntez,M.R.,&Grifn,P.A.(2006).Useofthesequentialinterceptmodelasanapproachtodecriminalization

of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 57(4), 544-549.

REFERENCES

25

Shapiro, G. K., Cusi, A., Kirst, M., O’Campo, P., Nakhost, A., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2015). Co-responding police-

mental health programs: a review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services

Research, 42(5), 606-620.

Skubby,D.,Bonne,N.,Novisky,M.,Munetz,M.R.,&Ritter,C.(2013).Crisisinterventionteam(CIT)programsin

rural communities: A focus group study. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(6), 756-764.

Steadman,H.J.,&Naples,M.(2005).Assessingtheeffectivenessofjaildiversionprogramsforpersonswith

serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 23(2), 163-

170.

Stelovich, S. (1979). From the hospital to the prison – Step forward in deinstitutionalization.” Hospital and

Community Psychiatry, 30(9), 618-620.

Swank,G.E.&Winer,D.(1976).Occurrenceofpsychiatric-disorderinacountyjailpopulation.American Journal

of Psychiatry, 133(11), 1331-33.

Taheri,S.(2016).Docrisisinterventionteamsreducearrestsandimproveofcersafety?Asystematicreview

and meta-analysis. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 27(1), 76-96.

Treatment Advocacy Center. (2015). Overlooked in the undercounted: The role of mental illness in fatal law

enforcement encounters. Retrieved from http://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/

overlooked-in-the-undercounted.pdf.

Whitmer,G.E.(1980).Fromhospitalstojails - FateofCalifornia’sde-institutionalizedmentally-ill.American

Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 50(1), 65-75.

The IU Public Policy Institute (PPI) delivers unbiased research and

data-driven, objective, expert policy analysis to help public,

private, and nonprot sectors make important decisions that

impact quality of life in Indiana and throughout the nation. As

a multidisciplinary institute within the IU School of Public and

Environmental affairs, we also support the Center for Criminal

Justice Research (CCJR) and the Indiana Advisory Commission on

Intergovernmental Relations (IACIR).

DESIGN BY

Karla Camacho-Reyes, Communications & Graphic Design

27

CENTER FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE RESEARCH

HORIZONTAL VERSION

CENTER FOR CRIMINAL JUSTICE RESEARCH

VERTICAL VERSION