JOURNAL OF APPLIED ECONOMETRICS

J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960–992 (2009)

Published online 22 April 2009 in Wiley InterScience

(www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/jae.1079

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS?

ANDREW MOUNTFORD

a

* AND HARALD UHLIG

b

a

Royal Holloway, University of London, UK

b

University of Chicago, IL, USA, and CEPR, London, UK

SUMMARY

We propose and apply a new approach for analyzing the effects of fiscal policy using vector autoregressions.

Specifically, we use sign restrictions to identify a government revenue shock as well as a government

spending shock, while controlling for a generic business cycle shock and a monetary policy shock. We

explicitly allow for the possibility of announcement effects, i.e., that a current fiscal policy shock changes

fiscal policy variables in the future, but not at present. We construct the impulse responses to three linear

combinations of these fiscal shocks, corresponding to the three scenarios of deficit-spending, deficit-financed

tax cuts and a balanced budget spending expansion. We apply the method to US quarterly data from 1955

to 2000. We find that deficit-financed tax cuts work best among these three scenarios to improve GDP, with

a maximal present value multiplier of five dollars of total additional GDP per each dollar of the total cut in

government revenue 5 years after the shock. Copyright

2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

1. INTRODUCTION

What are the effects of tax cuts on the economy? How much does it matter whether they are

financed by corresponding cuts of expenditure or by corresponding increases in government debt,

compared to the no-tax-cut scenario? These questions are of key importance to the science of

economics and the practice of policy alike. This paper aims to answer these questions by proposing

and applying a new method of identifying fiscal policy surprises in vector autoregressions.

The identification method used in this paper is an extension of Uhlig (2005)’s agnostic

identification method of imposing sign restrictions on impulse response functions. We extend

this method to the identification of multiple fundamental shocks. More precisely, we identify a

government revenue shock as well as a government spending shock by imposing sign restrictions on

the fiscal variables themselves as well as imposing orthogonality to a generic business cycle shock

and a monetary policy shock, which are also identified with sign restrictions. No sign restrictions

are imposed on the responses of GDP, private consumption, private non-residential investment

and real wages to fiscal policy shocks, and so the method remains agnostic with respect to the

responses of the key variables of interest.

The identification method is thereby able to address three main difficulties which typically arise

in the identification of fiscal policy shocks in vector autoregressions. Firstly, there is the difficulty

of distinguishing movements in fiscal variables caused by fiscal policy shocks from those which are

simply the automatic movements of fiscal variables in response to other shocks such as business

cycle or monetary policy shocks. Secondly, there is the issue of what one means by a fiscal policy

Ł

Correspondence to: Andrew Mountford, Department of Economics, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 961

shock. While there is agreement that a monetary policy shock entails a surprise rise in interest rates,

several competing definitions come to mind for fiscal policy shocks. Finally, one also needs to take

account of the fact that there is often a lag between the announcement and the implementation of

fiscal policy and that the announcement may cause movements in macroeconomic variables before

there are movements in the fiscal variables.

For the first problem we identify a business cycle shock and a monetary policy shock and

require that a fiscal shock be orthogonal to both of them. This filters out the automatic responses

of fiscal variables to business cycle and monetary policy shocks.

To address the second problem, we argue that macroeconomic fiscal policy shocks exist in a two-

dimensional space spanned by two basic shocks: a government revenue shock and a government

spending shock. Different fiscal policies such as balanced budget expansions can then be described

as different linear combinations of these two basic shocks. For example, a basic government

spending shock is defined as a shock where government spending rises for a defined period after

the shock, and which is orthogonal to the business cycle shock and the monetary policy shock.

We choose to restrict responses for a year following the shock in order to rule out shocks where

government spending rises on impact but then subsequently falls after one or two quarters. This

provides additional identifying power.

For the third problem, we also identify fiscal policy shocks with the identifying restriction that

the fiscal variable in question does not respond for four quarters, and then rises for a defined

period afterwards. Restricting the responses of impulse responses as a means of identification is

therefore particularly suitable for dealing with the announcement effect.

This paper therefore contributes to the recent and growing literature of employing vector

autoregressions to analyze the impact of fiscal policy shocks, complementing the existing large

literature analyzing monetary policy shocks; see, for example Leeper et al. (1996), Christiano

et al. (1999) and Favero (2001) for excellent surveys. Most of the previous literature has identified

fiscal shocks either by making assumptions about the sluggish reaction of some variables to fiscal

policy shocks (see, for example, Blanchard and Perotti, 2002; Fat

´

as and Mihov, 2001a,b; Favero,

2002; Gal

´

ı et al., 2007) or by using additional information such as the timing of wars, detailed

institutional information about the tax system and detailed historical study of policy decisions

or elections (see, for example, Ramey and Shapiro, 1998; Edelberg et al., 1999; Blanchard and

Perotti, 2002; Burnside et al., 2003; Eichenbaum and Fisher, 2004).

1

By contrast, this paper relies on macroeconomic time series data alone for shock identification

and does not rely on assumptions about the sluggish reaction of some variables to macroeconomic

shocks. Indeed it imposes no restrictions on the signs of the responses of the key variables of

interest—GDP, private consumption, private non-residential investment and real wages—to fiscal

policy shocks. The approach of this paper thus sharply differentiates it from previous studies

and provides an important complementary method of analysis which, being a purely vector

autoregressive approach, is automatically systematic and can be universally applied.

The method of identifying policy shocks using sign restrictions on impulse responses has been

introduced and applied to monetary policy in Uhlig (2005). Uhlig’s method is extended here by

imposing orthogonality restrictions to the business cycle and monetary policy shocks as well as sign

restrictions. Faust (1998) uses sign restrictions to identify monetary policy shocks, imposing them

1

There are a wide variety of other empirical studies investigating the effects of fiscal policy. The focus of this paper is

on the analysis of the effects of fiscal policy using vector autoregressions and so we do not attempt to summarize this

literature here. For an excellent survey see Hemming et al. (2000).

Copyright

2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960–992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

962 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

only at the time of impact, however, and Canova and De Nicol

`

o (2002, 2003) and Canova and Pina

(1998) identify monetary shocks using sign restrictions on impulse response correlations. Canova

and Pappa (2007) also identify fiscal shocks using sign restrictions on impulse response correlations

but control for monetary policy shocks using data from economies (states and countries) belonging

to monetary unions. More recently, Dedola and Neri (2007) have used sign restrictions to identify

technology shocks and Mountford (2005), Peersman (2005), Benati and Mumtaz (2007), Dungey

and Fry (2007) and Fry and Pagan (2007) have addressed the identification of multiple shocks

using sign restrictions.

We apply our new approach to US quarterly data, from 1955 to 2000. We use the same definitions

of government expenditure and revenue as Blanchard and Perotti (2002) in order not to obscure

the implications of our new methodological approach by using different data definitions. We show

that controlling for the business cycle shock is important when analyzing the consequences of

fiscal policy. By linearly combining our two base fiscal policy shocks—i.e., the government

revenue shock and the government spending shock—we analyze three policy scenarios: deficit-

spending, deficit-financed tax cuts and a balanced budget spending expansion. Comparing these

three scenarios, we find that a surprise deficit-financed tax cut is the best fiscal policy to stimulate

the economy, giving rise to a maximal present value multiplier of five dollars of total additional

GDP per each dollar of the total cut in government revenue 5 years after the shock. Furthermore,

we find that deficit spending weakly stimulates the economy, that it crowds out private investment

without causing interest rates to rise, and that it does not cause a rise in real wages.

Despite the novel methodology developed in this paper, the results are reasonably similar to

those of the existing literature. As with Blanchard and Perotti (2002), we find that investment falls

in response to both tax increases and government spending increases and that the multipliers

associated with a change in taxes to be much higher than those associated with changes in

spending. This latter result also accords with the analysis of Romer and Romer (2007), who

find large effects from exogenous tax changes. With regard to private consumption we find, in

common with Blanchard and Perotti (2002) and Gal

´

ı et al. (2007), that consumption does not

fall in response to an unexpected increase in government spending. However, in contrast to these

studies we do not find that consumption rises strongly. Our results show that the response of

consumption is small and only significantly different from zero on impact and are thus more in

line with those of Burnside et al. (2003), who find that private consumption does not change

significantly in response to a positive spending shock.

2

Finally, we find that real wages do not rise

in response to an increase in government spending and have a negative response on impact and at

longer horizons. Thus the responses of investment, consumption and real wages to a government

spending shock are difficult to reconcile with the standard Keynesian approach, although they are

also not the responses predicted by the benchmark real business cycle model either.

As an open issue for future research, we leave the question as to how far the responses

calculated here are consistent with general equilibrium modeling, or whether additional restrictions

from general equilibrium modeling ought to be imposed during estimation. Chung and Leeper

(2007) have recently pointed out that long-run budget balance needs to hold and that this implies

restrictions on the VAR coefficients. Put differently, it ought to be obvious that one cannot forever

2

Theoretical explanations for why consumption does not fall in response to a government spending shock in an infinite

horizon framework are given by Devereux et al. (1996), in a model with increasing returns to scale and Gal

´

ı et al. (2007)

in a model with both sticky prices and ‘Non-Ricardian’ agents.

Copyright

2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960–992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 963

stimulate the economy with deficit-financed tax cuts: they eventually need to be repaid. We agree

with Chung and Leeper that this issue is important and merits further attention.

The paper is comprised of three main sections. Section 2 describes the identification procedure

and the VAR. The empirically identified basic shocks are presented in Section 3, while Section 4

conducts policy analysis and compares the results with those of the existing literature in Section

4.6. The Appendix contains additional detail, in particular on the VAR framework and the sign

restriction methodology, as well as describing the data sources.

2. IDENTIFYING FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS

A fiscal policy shock is a surprise change in fiscal policy. However, there is no such thing as a

fiscal policy shock per se. Fiscal policy encompasses a wide variety of policies: there is an endless

list of types of incomes, for which the tax rules could be changed, or categories of government

spending, where changes could occur. In this paper we address the much broader and traditional

‘macro’-economic issue of the effects on the aggregate economy of aggregate fiscal variables.

Even so, there still remain a large set of possible policies since changes in fiscal policy could, for

example, be about changing the tax-debt mix for financing a given stream of government spending,

or about changing the level of spending for a given level of debt.

In this paper we view fiscal policy shocks as existing in a two-dimensional space spanned by two

basic impulse vectors: a government revenue shock and a government spending shock. We identify

each of these basic fiscal policy shocks by imposing a positive reaction of the impulse response of

the appropriate fiscal variable—i.e., government revenue or government spending— for quarters

k D 0,...,3 following the shock and by requiring it to be orthogonal to a business cycle shock

and a monetary policy shock, which in turn are also identified using sign restrictions. If we were

not to control for the state of the business cycle, it would be easy to end up confusing, for example,

an increase in government receipts due to a business cycle upturn with an upturn ‘caused’ by a

tax increase. Note that we do not require the two fiscal policy shocks to be mutually orthogonal.

Rather than simultaneously identifying all three (or all four) shocks, subject to the orthogonality

restrictions, we first identify the business cycle shock and monetary policy shock via a criterion

function based on the sign restrictions, thus ascribing as much movement as possible to these

shocks. The fiscal shocks are then identified via sign restrictions as well as the orthogonality

restrictions. This procedure may be reminiscent of a causal ordering. If the criterion function was

linear, one could linearly recombine the variables such that the first variable now corresponds to

that linear combination of the criterion function: a Cholesky decomposition would then make the

first shock explain as much as possible of the one-step-ahead prediction error in that first variable,

thus maximizing the criterion function. Since our criterion function is nonlinear and involves the

impulse responses for several periods, one could not rewrite the problem in this manner, but the

analogy may still be helpful to understand the procedure and the results.

A further thorny and well-understood challenge when identifying fiscal policy shocks is the

problem of the possible lag between the announcement and implementation of changes in fiscal

policy. Considering the potentially lengthy debates in legislatures about, say, a reduction in tax

rates, the change in government revenue is fairly predictable by the time the tax reduction actually

takes effect. Forward-looking individuals and firms can adjust their economic choices before that

date. While the tax change will happen eventually, the surprise of a change in fiscal policy

occurs earlier. Our identification procedure is easily adapted to deal with this problem by directly

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

964 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

identifying a shock for which there is a lag between the announcement and the implementation of

the change in fiscal policy. In particular, we shall identify announced fiscal policy shocks, where

government spending only rises in the fourth quarter following the shock but shows no reaction

beforehand.

3

Given the two basic fiscal shocks, different fiscal policy scenarios can be described as sequences

of different linear combinations of these two basic shocks. For example, we will define a balanced

budget expansionary fiscal scenario as a sequence of a linear combination of the two basic shocks

such that the increase in government spending is matched by the increase in tax revenue for a

sequence of five quarters, k D 0,...,4, following the initial shock.

2.1. The VAR and Identifying Restrictions

We use a VAR in GDP, private consumption, total government expenditure, total government

revenue, real wages, private non-residential investment, interest rate, adjusted reserves, the

producer price index for crude materials and the GDP deflator. The VAR system consists of

these 10 variables at a quarterly frequency from 1955 to 2000, has six lags, no constant or a time

trend, and uses the logarithm for all variables except the interest rate, where we have used the level.

The chosen approach largely dictates the choice of these variables. GDP, private consumption,

private investment and real wages are included as the focus of interest. Private consumption is also

included because the consumption–GDP ratio has predictive value for GDP, as Cochrane (1994)

has shown. Real wages are also included as Neoclassical and New Keynesian models tend to

predict different signs for the responses of real wages to deficit-spending shocks, with the former

predicting negative and the latter positive responses (see Ramey and Shapiro, 1998). The monetary

and price variables are there to identify monetary policy shocks. All the components of national

income are in real per capita terms. A more detailed description can be found in Appendix B.

The two fiscal variables in the VAR are defined in the same way as in Blanchard and Perotti

(2002). Thus total government expenditure is total government consumption plus total govern-

ment investment and total government revenues is total government tax revenues minus transfers.

Netting out transfer payments from the government revenue variable is a non-trivial decision, but

we have chosen to use Blanchard and Perotti’s (2002) data definitions in order to emphasize the

implications of the new identification technique rather than have the results obscured by using

different data definitions.

2.2. The Identifying Assumptions in Detail

An overview of our identifying sign restrictions on the impulse responses is provided in Table I.

A business cycle shock is defined as a shock which jointly moves output, consumption, non-

residential investment and government revenue in the same direction for four quarters following the

shock. Since we associate business cycles with the more substantial movements in these variables,

we identify the business cycle shock by a criterion function, which rewards large impulse responses

in the right directions more than small responses and penalizes responses of the wrong sign.

Such a co-movement is consistent with both demand and supply side shocks and hence the

approach remains ‘agnostic’ on the issue of the determinants of business cycle fluctuations. The

3

In this respect the identified shocks resemble a type of ‘news shock’ about fiscal policy and so are related to the shocks

identified by Beaudry and Portier (2003).

Copyright

2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960–992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 965

Table I. Identifying sign restrictions

Gov. revenue Gov. spending GDP, cons, non-res.inv. Interest rate Adjusted reserves Prices

Non-fiscal shocks

Business cycle CC

Monetary policy C

Basic fiscal policy shocks

Government revenue C

Government spending C

This table shows the sign restrictions on the impulse responses for each identified shock. ‘Cons’ stands for private

consumption and ‘Non-res. inv.’ stands for non-residential investment. A ‘C’ means that the impulse response of the

variable in question is restricted to be positive for four quarters following the shock, including the quarter of impact.

Likewise, a ‘’ indicates a negative response. A blank entry indicates that no restrictions have been imposed.

restriction that government revenues increase with output in the business cycle shock should

be emphasized. This is our crucial identifying assumption for fiscal policy shocks: when output

and government revenues move in the same direction, we essentially assume that this must be

due to some improvement in the business cycle generating the increase in government revenue,

not the other way around. We regard this is as a reasonable assumption and consistent with a

number of theoretical views. Furthermore, our identifying assumptions are close to minimal: some

assumptions are needed to say anything at all. The orthogonality assumption a priori excludes the

view that positive co-movements of government revenues and output are caused by some form of

short term ‘Laffer curve’ or ‘fiscal consolidation’ effect from a surprise rise in taxes.

4

A monetary policy shock moves interest rates up and reserves and prices down for four quarters

after the shock. These identifying restrictions are close to those used in Uhlig (2005). We also

require the monetary policy shock to be orthogonal to the business cycle shock. The main purpose

of characterizing the business cycle and monetary shocks is to filter out the effects of these shocks

on the fiscal variables. The additional orthogonalization among these two shocks has no effect on

that.

Fiscal policy shocks are identified only through restricting the impulse responses of the fiscal

variables and through the requirement that they are orthogonal to both business cycle shocks

as well as monetary policy shocks. As stated above, we identify two basic fiscal shocks—a

‘government spending shock’ and a ‘government revenue shock’— employing tight identifying

restrictions where the responses of fiscal variables are restricted for a defined period after the

shock. For example, a basic government spending shock is defined as a shock where government

spending rises for a year after the shock. These tight restrictions are designed to rule out very

transitory shocks to fiscal variables where, for example, government spending rises on impact

but falls after one or two quarters. Nonetheless we have checked that our results are robust to

weaker identifying restrictions where responses are only restricted on impact. Finally, it should be

noted that we do not restrict the behavior of government revenue when identifying the government

spending shock or vice versa. This is not necessary since all that is required to describe the two-

dimensional space of fiscal policy shocks are two linearly independent vectors. However, it is

4

The ‘Laffer curve’ is a phenomenon which, if it exists, may be expected to operate over the medium term and so would

not be ruled out by the short-run sign restrictions imposed. Indeed Figure 11 shows that the responses of government

revenue in response to a tax cut can be positive in the medium term. See Trabandt and Uhlig (2006), Giavazzi et al.

(1990, 2000) and Perotti (1999) for analysis on this issue.

Copyright

2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960–992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

966 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

possible to place restrictions on these shocks so that, for example, government revenue’s response

to a government spending shock is initially zero. An example of such restrictions are the year

delayed fiscal shocks in Figures 5 and 8, where fiscal responses are restricted to be zero for a year

following the announcement of the shock.

Details on the estimation as well as on the implementation of the identification strategies,

including these zero restrictions, are described in Appendix A and in Mountford and Uhlig (2002).

3. RESULTS

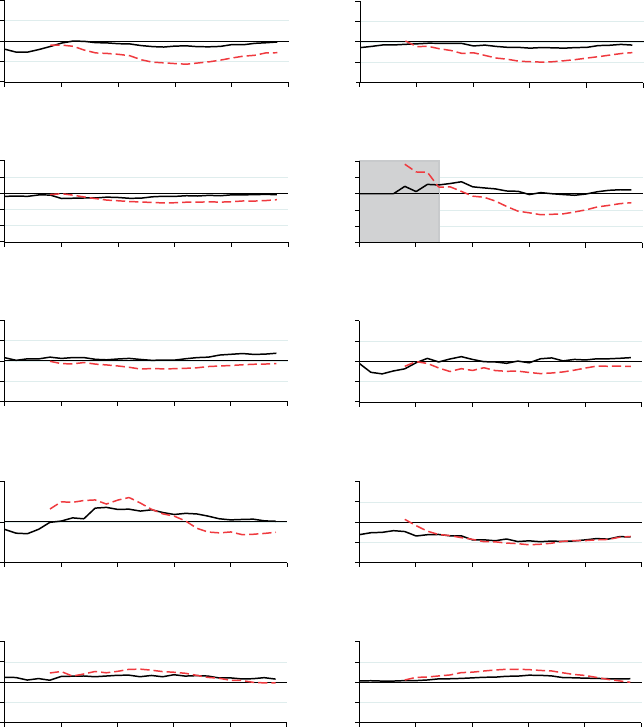

The identified fundamental shocks for each time period are displayed in Figure 1. The shocks are

identified for each draw from the posterior and the 16th, 50th and 84th quantiles plotted. The

impulse responses for these fundamental shocks are shown in Figures 2–9, where we have plotted

the impulse responses of all our 10 variables to the shocks. The figures plot the 16th, 50th and

84th quantiles of these impulse responses, calculated at each horizon between 0 and 24 quarters

after the shocks. The impulses restricted by the identifying sign restrictions are identified by the

shaded area in the figures.

3.1. The Business Cycle Shock

The identified business cycle shocks are plotted in the first panel of Figure 1, where the NBER

recession dates are shaded. The identified shocks correspond well with the NBER dates, with the

only anomalies being the 1981–82 recession, which is not picked up, and the short 1990–91

recession, which does not appear to be very different in scale from other clusters of negative

shocks.

The impulse responses of the business cycle shock are plotted in Figure 2. In response

to the business cycle shock, output, consumption, non-residential investment and government

revenue increase in the first four quarters by construction. Given that no restriction is placed

on these responses after four periods, it is notable that all of these responses are persistent.

Government revenues increase approximately twice as much in percentage terms as GDP. There

is no contradiction here, provided marginal tax rates are approximately twice average tax rates.

The persistence in the non-residential investment variable indicates that a business cycle shock

may increase the steady-state capital to labor ratio and so generate a higher level of steady-

state income, consumption and government revenue. It must be stressed that these responses

are consistent with both demand and supply side explanations of the business cycle and this

paper is agnostic on the issue of the relative importance and persistence of demand and supply

shocks.

The responses of the monetary variables and the government spending variable to the business

cycle shock were not restricted at all by the identification method, and their responses are quite

interesting. The interest rate rises and the adjusted reserves fall in response to a positive business

cycle shock. This could be caused by a systematic counter-cyclical response of monetary policy

over the sample period, which fits with the description of monetary policy given by Romer and

Romer (1994). The fall in adjusted reserves (compared to the no-business-cycle-shock scenario)

would indicate that this counter-cyclical response is rather strong.

Government expenditures, in contrast, do not behave in a counter-cyclical fashion. Rather, they

increase, slowly, with a positive business cycle shock. Thus, if a business cycle boom fills the

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 967

−5 −2.5

0 2.5

5

Percent

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Date

Business Cycle Shocks

−5 −2.5

0 2.5 5

Percent

1960 1970 1980 1990

2000

Date

Monetary Policy Shocks

−5 −2.5

0 2.5 5

Percent

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Date

Government Revenue Shocks

−5 −2.5

0 2.5 5

Percent

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Date

Government Spending Shocks

Figure 1. The shocks identified by the VAR: the business cycle shocks are identified first, the monetary policy

shocks are identified second and the government revenue and government spending shocks are identified third.

The shaded areas represent NBER recessions in the business cycle plot and a change of president in the

fiscal plots. This figure is available in color online at www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/jae

government’s coffers with cash, it will spend more eventually. Note again that, following Blanchard

and Perotti (2002), we chose the government expenditure variable to be government consumption

and investment in order to isolate changes in government expenditure from automatic changes over

the business cycle. Thus the government expenditure variable does not include transfer payments

which almost surely would automatically vary counter-cyclically.

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

968 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

-.5 0 .5 1 1.5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP

-.5 0 .5 1 1.5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

CONSUMPTION

-3 -1.5 0 1.5 3

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT SPENDING

-3 -1.5 0 1.5 3

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT REVENUE

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

REAL WAGES

-6 -3 0 3 6

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

NON-RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT

-.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

INTEREST RATE

-2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

ADJUSTED RESERVES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

PPIC

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP DEFLATOR

Figure 2. The business cycle shock ordered first. The shaded areas indicate the impulses directly restricted by

the identification procedure. This figure is available in color online at www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/jae

3.2. The M onetary Policy Shock

The identified monetary policy shocks are plotted in the second panel of Figure 1. Again these

identified shocks correspond well with the existing literature, such as Bernanke and Mihov’s (1998)

plot of monetary policy stance, and are on average negative (indicating a loose policy stance) in

the late 1970s, positive (indicating a tight policy stance) in the early 1980s, as well as being more

volatile in the Volcker experiment period, 1979–82.

The response to a monetary policy shock is shown in Figure 3. Note that we have constructed

the monetary policy shock to be orthogonal to the business cycle shock shown in Figure 2. Thus

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 969

-.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP

-.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

CONSUMPTION

-2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT SPENDING

-2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT REVENUE

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

REAL WAGES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

NON-RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT

-.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

INTEREST RATE

-3 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

ADJUSTED RESERVES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

Quarters After the Shock

PPIC

-2 -1 0 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

GDP DEFLATOR

Figure 3. The monetary policy shock ordered second. The shaded areas indicate the impulses directly restricted

by the identification procedure. This figure is available in color online at www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/

jae

this shock represents that part of the unanticipated quarterly change in monetary policy that

is not accounted for by systematic responses over the quarter to unanticipated business cycle

shocks. A consequence of our identification strategy is that if, rather counter-intuitively, monetary

policy shocks should be such that surprise rises in the interest rate cause short-term increases in

output, consumption and investment, then these effects would be captured by the business cycle

shock shown in Figure 2, not by the monetary shock shown here. Thus output, consumption and

investment in Figure 3 have a propensity to fall in the short term almost by construction and

they do, although interestingly by very little. Over the medium term, monetary policy shocks

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

970 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

-1 -.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP

-1 -.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

CONSUMPTION

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT SPENDING

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT REVENUE

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

REAL WAGES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

NON-RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT

-.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

INTEREST RATE

-2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

ADJUSTED RESERVES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

PPIC

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP DEFLATOR

Figure 4. The basic government revenue shock, identified by orthogonality to the business cycle shock and

monetary policy shock as well as a positive impulse response function of government revenues for four

quarters after the shock. The restriction is indicated by the shaded area on the graph. This figure is available

in color online at www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/jae

are associated with a marginally lower interest rate and increases in income, consumption and

wages. These results are thus not inconsistent with the findings in Uhlig (2005): there, without

orthogonality to the business cycle shock, sign restriction methods do not deliver a clear direction

for real GDP in response to a surprise rise in interest rates.

What is a little surprising is the rise in government revenue in response to the rise in interest

rates. One plausible, although not the only, explanation for this is that over the sample period

monetary and fiscal policy was coordinated so that a monetary tightening was accompanied by a

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 971

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

CONSUMPTION

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT SPENDING

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT REVENUE

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

REAL WAGES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

NON-RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT

-.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

INTEREST RATE

-2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

ADJUSTED RESERVES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

PPIC

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP DEFLATOR

Figure 5. The announced or anticipated basic government revenue shock, identified by orthogonality to

the business cycle shock and monetary policy shock as well as a zero impulse response for the first

four quarters and a positive impulse response function for the next four quarters of government revenues.

The restriction is indicated by the shaded area on the graph. This figure is available in color online at

www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/jae

fiscal tightening via an increase in taxes. If this were the case then there would be a danger that

requiring fiscal shocks to be orthogonal to monetary policy shocks will cause biases in the results.

For this reason we have checked the robustness of our identified fiscal shocks by identifying

them both second (orthogonal to only the business cycle shock) and third (orthogonal to both

the business cycle and monetary policy shocks). We find that the responses of the real variables

are very similar in both these specifications and hence any bias is small. This may be because

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

972 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

CONSUMPTION

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT SPENDING

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT REVENUE

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

REAL WAGES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

NON-RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT

-.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

INTEREST RATE

-2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

ADJUSTED RESERVES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

PPIC

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP DEFLATOR

Figure 6. A comparison of the median responses of an anticipated (solid line) and unanticipated (dashed line)

government revenue shock, where the impulses are plotted so that the time period of the implementation of

the tax rise is the same. This figure is available in color online at www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/jae

monetary policy shocks do not appear have a large effect on real macroeconomic variables. We

conclude from this that controlling for the monetary policy shock is not important when analyzing

the consequences of fiscal policy; see Mountford and Uhlig (2002) for a greater discussion of this

issue.

3.3. The B asic Government Revenue Shock

A basic government revenue shock is identified as a shock that is orthogonal to the business cycle

and monetary policy shock and where government revenue rises for a year after the shock. The

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 973

-1 -.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP

-1 -.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

CONSUMPTION

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT SPENDING

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT REVENUE

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

REAL WAGES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

NON-RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT

-.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

INTEREST RATE

-2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

ADJUSTED RESERVES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

PPIC

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP DEFLATOR

Figure 7. The basic government expenditure shock, identified by orthogonality to the business cycle shock

and monetary policy shock as well as a positive impulse response function of government expenditures for

four quarters after the shock. The restriction is indicated by the shaded area on the graph. This figure is

available in color online at www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/jae

identified government revenue shocks are plotted in the third panel of Figure 1, where the change

from shaded to non-shaded areas denotes changes in presidential terms. These identified shocks

correspond, in part at least, with Romer and Romer’s (2007) measure of exogenous tax changes,

in that the shocks are on average negative in the mid 1960s and mid 1980s and positive in the

early 1990s. They also clearly pick up the large effects of the 1975 Tax Reduction Act.

The impulse responses for this shock are displayed in Figure 4. Figure 4 shows that the responses

of the real variables of interest to a standard government revenue shock are intuitive. GDP,

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

974 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0

5 10

15 20

25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP

-1

-.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5

10

15

20

25

Quarters After the Shock

CONSUMPTION

-3 -2

-1 0 1 2

Percent

0

5 10

15 20

25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT SPENDING

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0

5

10

15

20

25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT REVENUE

-1

-.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0

5 10 15

20

25

Quarters After the Shock

REAL WAGES

-4 -2

0 2 4

Percent

0 5

10

15

20

25

Quarters After the Shock

NON-RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT

-.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10

15 20

25

Quarters After the Shock

INTEREST RATE

-2

-1 0 1 2

Percent

0

5 10 15 20

25

Quarters After the Shock

ADJUSTED RESERVES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0

5 10 15

20 25

Quarters After the Shock

PPIC

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5

10 15

20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP DEFLATOR

Figure 8. The announced or anticipated basic government expenditure shock, identified by orthogonality to

the business cycle shock and monetary policy shock as well as a zero impulse response for the first four

quarters and a positive impulse response function for the next four quarters of government expenditures.

The restriction is indicated by the shaded area on the graph. This figure is available in color online at

www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/jae

consumption and investment fall in response to an increase in revenue and real wages also fall,

although with a lag. The responses of interest rates and prices are less intuitive as interest rates

rise and reserves fall in response to a rise in revenue. Although no restriction is placed on the

behavior of government spending for this shock, government spending follows the shape of the

GDP and consumption responses and falls before recovering.

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 975

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

CONSUMPTION

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT SPENDING

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT REVENUE

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

REAL WAGES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

NON-RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT

-.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

INTEREST RATE

-2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

ADJUSTED RESERVES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

PPIC

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP DEFLATOR

Figure 9. A comparison of the median responses of an anticipated (solid line) and unanticipated (dashed line)

government spending shock, where the impulses are plotted so that the time period of the implementation

of the increase in government spending is the same.

3.4. The Anticipated Government Revenue Shock

We also identify a year delayed shock where government revenue is restricted to rise only after a

year.

5

The responses of this shock are displayed in Figure 5. They show an intuitive ‘announcement

5

The zero restrictions for government revenue for the anticipated tax shock implicitly assume that, should GDP fall in

response to this announcement, taxes are temporarily raised to cover the associated decline in revenues during the year

before implementation (see Leeper et al. 2008). It should be noted that these implicit tax rises should be depressing

GDP further and yet the negative response of GDP is small and so this consideration does not go against our finding

Copyright

2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960–992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

976 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

effect’ as the anticipated rise in revenues immediately depresses output and consumption. This

accords with our intuition regarding the optimal smoothing behavior of individuals and firms.

Interest rates also fall with this drop in output, which is also intuitive.

6

The median responses of the unanticipated and anticipated shocks are compared in Figure 6,

where the responses of the unanticipated shocks are shifted forward so that the implementation of

the revenue shock is in the same time period. Figure 6 shows that the responses to an anticipated

government revenue shock, while similar to those of the unanticipated shocks in terms of their

sign, are somewhat smaller, perhaps because announced policies move fiscal variables by less than

unanticipated changes.

7

3.5. The B asic Government Spending Shock

A basic government revenue shock is identified as a shock that is orthogonal to the business

cycle and monetary policy shock and where government spending rises for a year after the shock.

The identified government spending shocks are plotted in the fourth panel of Figure 1, where the

change from shaded to non-shaded areas denotes changes in presidential terms. These identified

shocks show that government spending shocks were predominantly positive in the mid 1960s and

early 1990s and predominantly negative around 1960 and in the early 1970s. In the the 1990s

government spending appears to be more stable than average, with relatively few shocks reaching

the 2.5% level in absolute terms.

The impulse responses for this shock are displayed in Figure 7. Figure 7 shows that the basic

government spending shock stimulates output during the first four quarters, although only weakly,

and has only a very weak effect on private consumption. It also reduces investment, although

interestingly not via higher interest rates. Real wages do not respond positively to the government

spending shock and indeed are negative on impact and in the medium term, which is more in

accordance with neoclassical than New Keynesian models of government spending (see Ramey

and Shapiro, 1998). Although no restriction is placed on the behavior of government revenue, this

does not change very significantly and so the basic government spending shock will resemble a

fiscal policy shock of deficit spending, whose responses are displayed in Figure 10 below. The

response of prices to the increase in government spending is a little puzzling since both the

GDP deflator and the producer price index for crude materials show a decline. Although this is

a counter-intuitive result, it should be noted that this negative relationship between prices and

government spending has also been found in other studies (see, for example Canova and Pappa,

2007; Edelberg, et al., 1999. Fat

´

as and Mihov, 2001a).

that anticipated tax shocks have a much weaker response than unanticipated shocks. Further, note that an alternative

specification for the anticipated tax shock, which places no restrictions on tax revenues for the year before implementation,

could easily be implemented.

6

When analyzing anticipated tax shocks, we implicitly assume that our VAR approach approximates a time series model,

in which news about tax shocks are always about the next annual tax change and not about subsequent ones. Otherwise,

overlapping news or a moving average process for taxes with two or more lags may result in problems with invertibility

and an appropriate VAR representation, as Leeper et al. (2008) have shown.

7

Changes in fiscal policy may be the result of the systematic component of fiscal policy—unrelated to the business

cycle— rather fiscal policy shocks, as Liu et al. (2007) have argued is the case for monetary policy shocks. However, we

leave the joint identification of fiscal policy regime shifts and fiscal policy shock for future work.

Copyright

2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960–992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 977

3.6. The Anticipated Government Spending Shock

We also identify a year delayed shock where government spending is restricted to rise only after

a year. The responses of this shock are displayed in Figure 8. They again show an intuitive

‘announcement’ effect on impact as the anticipated rise in spending immediately has a positive

effect on output and interest rates. Again this is consistent with smoothing behavior by individuals

and firms. The median responses of the unanticipated and anticipated shocks are compared

in Figure 9, where the responses of the unanticipated shocks are shifted forward so that the

implementation of the spending shock is in the same time period. Figure 9 shows that the responses

to an anticipated government spending shock appear more persistent and stronger than for the

unanticipated shocks and investment is no longer crowded out by the increase in government

spending. This is an interesting and slightly puzzling result; however, it should be noted that the

interpretation of these responses in the medium term is clouded by the marginal cut in taxes after

a year. From Figure 5 this would have a significant expansionary effect and this may be the cause

of the persistent positive effects on income and consumption. In Section 4.1 below we demonstrate

a straightforward method for accounting for such changes when performing policy analysis.

4. POLICY ANALYSIS

We can use the basic shocks identified in the previous section to analyze the effects of different

fiscal policies. We view different fiscal policy shocks as different linear combinations of the basic

fiscal policy shocks. There are clearly a huge number of possible fiscal policies we could analyze,

so here we restrict ourselves to comparing three popularly analyzed fiscal policies. A deficit-

spending shock, a deficit financed tax cut and a balanced budget spending shock. We first detail

how the impulse responses for these policies are generated.

4.1. CALCULATING THE IMPULSE RESPONSES FOR DIFFERENT FISCAL POLICY

SCENARIOS

Our methodology regards different fiscal policy scenarios as being different combinations of the

two basic shocks over a sequence of several quarters. For example, a government spending scenario

where government spending is raised by 1% for four quarters while government revenue remains

unchanged is the linear combination of the sequence of the two basic shocks that generates these

responses in the fiscal variables as the combined impulse response. More formally, denoting r

j,a

k

as the response at horizon k of variable j to the impulse vector a, then the above policy requires

that

0.01 D

k

jD0

r

GS,BGS

k jBGS

j

C r

GS,BGR

k jBGR

j

for k D 0,...K

0 D

k

jD0

r

GR,BGS

k jBGS

j

C r

GR,BGR

k jBGR

j

for k D 0,...K

where K D 4, GS and GR stand for government expenditure and government revenue, and BGS

j

and BGR

j

are respectively the scale of the standard basic government spending and revenue shocks

in period j.

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

978 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

-1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP

-1 -.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

CONSUMPTION

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT SPENDING

-6 -3 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT REVENUE

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

REAL WAGES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

NON-RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT

-.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

INTEREST RATE

-2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

ADJUSTED RESERVES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

PPIC

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP DEFLATOR

.50-.5

Figure 10. The deficit spending policy scenario where government spending is raised by 1% for four

quarters with government revenues remaining unchanged. These impulses are linear combinations of a

sequence of the basic shocks displayed in Figures 4 and 7. This figure is available in color online at

www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/jae

We analyze three key policy scenarios below: deficit spending, a deficit-financed tax cut and a

balanced budget spending expansion. It should be clear, however, that other scenarios of interest

can be analyzed in this manner as well.

4.2. A Deficit-Spending Fiscal Policy Scenario

The impulse responses for a deficit spending fiscal policy scenario are shown in Figure 10. The

policy scenario is designed as a sequence of basic fiscal shocks such that government spending

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 979

rises by 1% and tax revenues remain unchanged for four quarters following the initial shock.

As noted above, the standard basic government spending shock does not change tax revenues

significantly, so the impulses in Figure 10 and are similar to those in Figure 7. Thus the deficit

spending scenario stimulates output and consumption during the first four quarters although only

weakly, it reduces non-residential investment and it produces a counter-intuitive response for

prices.

4.3. A Deficit-Financed Tax Cut Fiscal Policy Scenario

The impulse responses for a deficit financed tax cut fiscal policy scenario are shown in Figure 11.

The policy scenario is designed as a sequence of basic fiscal shocks such that tax revenues fall by

1% and government spending remains unchanged for four quarters (including the initial quarter)

following the initial shock. The responses look very similar to a mirror image of the responses to

the basic government revenue shock in Figure 4. Thus the tax cut stimulates output, consumption

and investment significantly, with the effect peaking after about 3 years. The effect on prices is

initially negative but subsequently positive following the rise in output.

4.4. The Balanced B udget Spending Policy Scenario

The balanced budget spending policy scenario is identified by requiring both government revenues

and expenditures to increase in such a way that the increase in revenues and expenditure is equal

for each period in the four-quarter window following the initial shock. For ease of comparison

we choose a sequence of basic fiscal shocks such that government spending rises by 1% and

government revenue rises by 1.28%. Government revenue rises by more than government spending

since over the sample government revenue’s share of GDP is 0.162, while that of government

spending is 0.208; thus we require government revenue to rise by (0.208/0.162)%. The results

are shown in Figure 12. These show that on impact there is a small expansionary effect on GDP

but thereafter the depressing effects of the tax increases dominate the spending effects, and GDP,

consumption and investment fall.

4.5. Measures of the Effects of Policy Scenarios

To compare the effects of one fiscal scenario with another it is useful to define summary measures

of the effects of each fiscal scenario. One measure used in the literature is the ratio of the response

of GDP at a given period to the initial movement of the fiscal variable (see, for example, Blanchard

and Perotti, 2002; Canova and Pappa, 2007). We refer to this as the impact multiplier. We report

the impact multipliers of the deficit financed tax cut and deficit-spending policy scenarios below

in Tables III and IV.

However, we think a measure of the impact of a scenario along the entire path of the responses

up to a given period is also useful. In Figure 13 we have therefore plotted the present value of

the impulse responses of GDP and the fiscal variables for the deficit-financed tax cut and the

deficit-spending policy scenarios. We have also calculated a present value multiplier for these

scenarios, which we display in Table II. To calculate the present value multiplier we use the

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

980 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

-.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP

-.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

CONSUMPTION

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT SPENDING

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT REVENUE

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

REAL WAGES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

NON-RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT

-.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

INTEREST RATE

-2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

ADJUSTED RESERVES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

PPIC

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP DEFLATOR

Figure 11. The deficit-financed tax cut policy scenario where government spending remains unchanged

and government revenue is reduced by 1% for four quarters. These impulses are linear combinations of

a sequence of the basic shocks displayed in Figures 4 and 7. This figure is available in color online at

www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/jae

following formula:

Present value multiplier at lag k D

k

jD0

1 C i

j

y

j

k

jD0

1 C i

j

f

j

1

f/y

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 981

-1.5 -1 -.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP

-1.5 -1 -.5 0 .5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

CONSUMPTION

-3 -2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT SPENDING

-6 -3 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GOVERNMENT REVENUE

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

REAL WAGES

-6 -4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

NON-RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT

-.5 0 .5

Percent

0

5

10

15

20

25

Quarters After the Shock

INTEREST RATE

-2 -1 0 1 2

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

ADJUSTED RESERVES

-4 -2 0 2 4

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

PPIC

-1 -.5 0 .5 1

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

GDP DEFLATOR

Figure 12. The balanced budget policy scenario where government spending is raised by 1% for four quarters

and government revenues raised so that the increased revenue matches the increased spending. These impulses

are linear combinations of a sequence of the basic shocks displayed in Figures 4 and 7. This figure is available

in color online at www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/jae

where y

j

is the response of GDP at period j, f

j

is the response of the fiscal variable at period j,

i is the average interest rate over the sample, and f/y is the average share of the fiscal variable in

GDP over the sample. We use the median multiplier in all cases.

Table II and Figure 13 and tell the same story. They show that in present value terms tax cuts

have a much greater effect on GDP than government spending. The present value of the GDP

response to a deficit spending scenario becomes insignificant after 2 years, whereas that for the

deficit-financed tax cut is significantly positive throughout. Figure 13 also shows that the standard

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

982 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

-2 0 2 4 6 8 10 12

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

DISCOUNTED CUMULATIVE GOVT SPENDING

-12 -9 -6 -3 0 1.5

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

DISCOUNTED CUMULATIVE GDP RESPONSES

DEFICIT SPENDING

-10 -5 0 5 10 15 20

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

DISCOUNTED CUMULATIVE GOVT REVENUE

-1 0 2 4 6 8 10 12

Percent

0 5 10 15 20 25

Quarters After the Shock

DISCOUNTED CUMULATIVE GDP RESPONSES

DEFICIT FINANCED TAX CUT

DISCOUNTED CUMULATIVE RESPONSES TO POLICY SHOCKS

Figure 13. The present value of the impulses for GDP and the changing fiscal variable for the deficit-spending

policy scenario and the deficit-financed tax cut policy scenario displayed in Figures 10 and 11. This figure

is available in color online at www.interscience.wiley.com/journal/jae

Table II. Present value multipliers of the policy scenarios

1 qrt 4 qrts 8 qrts 12 qrts 20 qrts Maximum

Deficit-financed tax cut 0.29 0.52 1.63 5.25 4.55 5.25 (qrt 12)

Deficit spending 0.65 0.46 0.07 0.26 2.07 0.65 (qrt 1)

This table shows the present value multipliers for a deficit financed tax cut policy scenario and for a deficit-spending

fiscal policy scenario. The multipliers given are the median multipliers in both cases.

Copyright

2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960–992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 983

error of the present value multiplier becomes very large for the deficit-financed tax cut at later

time periods.

8

4.6. Comparison of Results with the Existing Literature

Despite the novel methodology used in this paper, there are many similarities to results obtained

elsewhere in the existing literature. There are, however, also important differences, which we shall

discuss below. As we have used Blanchard and Perotti’s (2002) data definitions for the fiscal

variables and use a very similar sample period, it is natural to compare our results most closely

with their paper. We do this in the following subsection. We compare our results to other studies

in a further subsection.

4.6.1 Comparison with Blanchard and Perotti (2002)

The impact multipliers, defined above, are compared with those of Blanchard and Perotti (2002)

in Tables III and IV.

For the deficit-financed tax cut, Table III shows that our results are very comparable with

Blanchard and Perotti’s. In both studies the effect on output of a change in tax revenues is

persistent and large. The size of the impact multiplier is greater in our results than in Blanchard

and Perotti’s, although in both studies the impact multipliers of the tax cut scenario are greater

than those of the spending scenario.

For the spending scenario, Table IV shows that size of the impact multipliers associated with

increased government spending is smaller than Blanchard and Perotti’s, but that the timing has a

similar pattern in the sense that the largest impact multipliers are in the periods close to the impact

of the initial shock and with the responses after a year being insignificant.

With respect to the responses of investment again the two studies are similar. In both Blanchard

and Perotti’s and in our study investment falls in response to both tax increases and government

Table III. Impact multipliers of deficit-financed tax cut policy scenarios

1 qrt 4 qrts 8 qrts 12 qrts 20 qrts Maximum

Mountford and Uhlig

GDP 0.28 0.93 2.05 3.41 2.59 3.57 (qrt 13)

Tax revenues 1.00 1.00 0.06 1.05 1.03

Gov. spending 0.00 0.00 0.27 0.43 0.48

Blanchard and Perotti

(2002)

GDP 0.70 1.07 1.32 1.30 1.29 1.33 (qrt 7)

Tax revenues 0.74 0.31 0.17 0.16 0.16

Gov. spending 0.06 0.10 0.17 0.20 0.20

This table shows the impact multipliers for a deficit-financed tax cut fiscal scenario for various quarters after the initial

shock and compares them to similar measures from Blanchard and Perotti (2002 Table III). The multiplier represents the

effect in dollars of a one-dollar cut in taxes at the first quarter. For the Mountford and Uhlig results this is calculated

with the formula: Multiplier for GDP D

GDP response

Initial fiscal shock

/(Average fiscal variable share of GDP), where the median

responses are used in all cases. On the calculation of the Blanchard and Perotti (2002) multipliers see Blanchard and

Perotti (2002 section V).

8

The median multiplier becomes negative at later time periods for both the deficit spending and deficit-financed tax cut

shocks but in both cases these negative multipliers are not significant.

Copyright

2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960–992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

984 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

Table IV. Impact multipliers of a deficit-spending policy scenario

1 qrt 4 qrts 8 qrts 12 qrts 20 qrts Maximum

Mountford and Uhlig

GDP 0.65 0.27 0.74 1.19 2.24 0.65 (qrt 1)

Gov. spending 1.00 1.00 0.90 0.37 0.32

Tax revenues 0.00 0.00 0.33 0.87 2.04

Blanchard and Perotti

(2002)

GDP 0.90 0.55 0.65 0.66 0.66 0.90 (qrt 1)

Gov. spending 1.00 1.30 1.56 1.61 1.62

Tax revenues 0.10 0.18 0.33 0.36 0.37

This table shows the impact multipliers for a deficit-spending fiscal scenario for various quarters after the initial shock

and compares them to similar measures from Blanchard and Perotti (2002 Table IV). The multiplier represents the effect

in dollars of a one-dollar increase in spending at the first quarter. For the Mountford and Uhlig results this is calculated

with the formula: Multiplier for GDP D

GDP response

Initial fiscal shock

/(Average fiscal variable share of GDP), where the median

responses are used in all cases. On the calculation of the Blanchard and Perotti (2002) multipliers see Blanchard and

Perotti (2002 section V).

spending increases. With regard to consumption the results have some similarities to Blanchard and

Perotti’s in that consumption does not fall in response to a spending shock. However, in Blanchard

and Perotti (2002) consumption rises significantly in response to a spending shock, whereas in our

analysis consumption does not move by very much.

9

As Figure 10 shows, consumption’s response

is only significantly positive on impact and then by only a small amount. Thereafter its response is

insignificant. Finally, we find that real wages do not rise in response to an increase in government

spending and have a negative response on impact and at longer horizons. Thus, taken together,

these findings are difficult to reconcile with the standard Keynesian approach, although they are

also not the responses predicted by the benchmark real business cycle model.

4.6.2 Comparison with Other Studies

With regard to other studies in the literature, not only are there differences in methodology but

also in the definitions of the fiscal variables. There is thus no shortage of potential sources for

differences in results. Nevertheless, there is still some common ground in the results of this paper

and previous work. For example, consider the recent work by Burnside et al. (2003), which builds

on the work of Ramey and Shapiro (1998) and Edelberg et al. (1999) in using changes in military

purchases associated with various wars to identify government spending shock. They find that

private consumption does not change significantly in response to a government spending shock.

However, in contrast to our results they find that investment has an initial, transitory positive

response to the spending shock.

4.7. Variance of the Policy Analysis

Clearly there is a considerable degree of uncertainty in the numbers displayed in Tables III and IV,

as they are based on the maximum multipliers from the median impulse responses. An advantage

of the Bayesian approach used in our analysis is that it naturally provides a measure of the standard

9

See also Gali et al. (2007), who also find a significantly positive consumption response.

Copyright

2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960–992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

WHAT ARE THE EFFECTS OF FISCAL POLICY SHOCKS? 985

errors for this policy analysis. Standard errors can easily be calculated for each policy scenario by

taking the maximum and minimum multipliers of GDP and their corresponding lag for each of

the draws from the posterior. These maxima and minima can then be ordered and the 16th, 50th

and 84th percentiles reported. This is done in Table V.

Table V supports the conclusions above. The maximum expansionary effect of a deficit-spending

scenario is much below that of the tax revenue scenario. Indeed the upper confidence limit of the

deficit-spending scenario is below the lower confidence limit of the tax cut scenario. For the tax

cut the maximum effects are significantly positive and the minimum effects are insignificantly

different from zero.

The results in Table V are usefully related to the impulse responses in Figures 10–12. For

the tax cut the maximum multipliers occur after two or more years, whereas for the balanced

budget and deficit-spending scenarios the maximum effects occur at short lags and the minimum

effects at longer lags. Since the variance of the impulse responses for these scenarios appears to

increase at longer lag lengths, we also look at the maximum and minimum multipliers of the two

spending scenarios in the first year after the initial shock. In this case we now get the result that

the deficit-spending scenario’s minimum multiplier is insignificantly different from zero but that

for the balanced budget spending scenario is still significantly negative.

These statistics relate to the distribution of the maximum and minimum impact multiplier

effects of each fiscal scenario. For each draw the maximum and minimum fiscal multiplier is

calculated and the 16th, 50th and 84th percentiles of these results are displayed. The multiplier

statistic is calculated in terms of the initial, lag 0, fiscal shock as follows: multiplier for

GDP D

GDP response

Fiscal shock at Lag 0

/(Average fiscal variable share of GDP).

4.8. Policy Conclusions

An important lesson one can draw from the results is that while a deficit-financed expenditure

stimulus is possible, the eventual costs are likely to be much higher than the immediate benefits.

Suppose that government spending is increased by 2%, financed by increasing the deficit: this

results, using the median values from Table V, at maximum, in less than a 2% increase in GDP. But

the increased deficit needs to be repaid eventually with a hike in taxes. Even ignoring compounded

Table V. Maximum and minimum impact multipliers of fiscal policy scenarios

Fiscal scenario Maximum multiplier Minimum multiplier

Median

multiplier

Confidence interval

16th, 84th quantiles

Median

multiplier

Confidence interval

16th, 84th quantiles

Deficit spending 0.91 0.68, 1.37 2.88 4.99, 0.80

lag 4 lag 2, lag 6 at lag 20 lag 24, lag 8

Balanced budget 0.47 0.19, 0.84 5.84 9.46, 3.63

lag 1 lag 1, lag 1 at lag 19 lag 15, lag 11

Tax cut 3.81 2.58, 5.49 0.19 0.11, 0.36

lag 12 lag 15, lag 13 at lag 24 lag 24, lag 1

Deficit spending 0.79 0.59, 1.05 0.09 0.21, 0.31

in first year lag 4 lag 4, lag 1 at lag 4 lag 4, lag 2

Balanced budget 0.45 0.16, 0.79 0.71 1.11, 0.40

in first year at lag 3 lag 1, lag 1 at lag 4 lag 1, lag 2

Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Appl. Econ. 24: 960 –992 (2009)

DOI: 10.1002/jae

986 A. MOUNTFORD AND H. UHLIG

interest rates, this would require a tax hike of over 2%.

10

This tax hike results in a greater than

7% drop in GDP. Thus, unless the policy maker’s discount rate is very high, the costs of the

expansion will be much higher than the initial benefit.

This general line of reasoning is consistent with the balanced budget spending scenario

whose impulses are shown in Figure 12. This shows that when government spending is financed

contemporaneously the contractionary effects of the tax increases outweigh the expansionary effects

of the increased expenditure after a very short time.