fiScal

DecenTralizaTion

in zambia

Sec1:i

United Nations Human Settlements Programme

Nairobi 2012

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION

IN ZAMBIA

ii

e Global Urban Economic Dialogue Series

Fiscal Decentralisation in Zambia

First published in Nairobi in 2012 by UN-HABITAT.

Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme 2012

HS/034/12E

ISBN (Series): 978-92-1-132027-5

ISBN (Volume): 978-92-1-132449-5

Disclaimer

e designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do

not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of

the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area

or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers of boundaries.

Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reect those of the United

Nations Human Settlements Programme, the United Nations, or its Member States.

Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated.

Acknowledgements:

Director: Naison Mutizwa-Mangiza

Chief Editor and Manager: Xing Quan Zhang

Principal Author: Andrew Chitembo

English Editor: Roman Rollnick

Design and Layout: Peter Cheseret

Assistant: Agnes Ogana

iii

Urbanization

is one of the

most powerful,

irreversible forces

in the world. It

is estimated that

93 percent of

the future urban

population growth

will occur in the

cities of Asia and

Africa, and to a lesser extent, Latin America

and the Caribbean.

We live in a new urban era with most of

humanity now living in towns and cities.

Global poverty is moving into cities, mostly

in developing countries, in a process we call

the urbanisation of poverty.

e world’s slums are growing and growing

as are the global urban populations. Indeed,

this is one of the greatest challenges we face in

the new millennium.

e persistent problems of poverty and

slums are in large part due to weak urban

economies. Urban economic development is

fundamental to UN-HABITAT’s mandate.

Cities act as engines of national economic

development. Strong urban economies

are essential for poverty reduction and the

provision of adequate housing, infrastructure,

education, health, safety, and basic services.

e Global Urban Economic Dialogue series

presented here is a platform for all sectors

of the society to address urban economic

development and particularly its contribution

to addressing housing issues. is work carries

many new ideas, solutions and innovative

best practices from some of the world’s

leading urban thinkers and practitioners

from international organisations, national

governments, local authorities, the private

sector, and civil society.

is series also gives us an interesting

insight and deeper understanding of the wide

range of urban economic development and

human settlements development issues. It will

serve UN member States well in their quest

for better policies and strategies to address

increasing global challenges in these areas

Joan Clos

Under-Secretary-General

of the United Nations,

Executive Director, UN-HABITAT

FOREWORD

iv

CONTENTS

FOREWORD III

CONTENTS IV

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS VI

LISTS OF FIGURES, GRAPHS, MAPS AND TABLES VIII

CHAPTER 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF ZAMBIA 1

Administrative Structure and Functions 1

Central Government 2

Local Government 3

LEGAL FRAMEWORK 4

Constitutional Provisions 4

Statutory Provisions 5

DECENTRALISATION 7

Justication 7

Decentralised Development Planning 8

Situation to Date 8

PUBLIC EXPENDITURE RELATIVE TO GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT 8

FISCAL DECENTRALISATION INDICATORS and PERFORMANCE 9

Global Indicators and Ranges 9

The Zambian Indicators 10

The Zambian Performance 11

CHAPTER 2 OVERVIEW OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE 13

PUBLIC FINANCE 13

Allocation 13

Distribution 14

Stabilisation 14

LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE AS AN ASPECT OF PUBLIC FINANCE 15

Why Local Government Finance? 15

The Role of Local Government Finance in Zambia 15

Allocation 15

Distribution 15

Stabilisation 16

REVENUE SOURCES FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN ZAMBIA 16

CHAPTER 3 THE CONCEPT OF FISCAL DECENTRALISATION 17

WHAT IS FISCAL FEDERALISM AND FISCAL DECENTRALISATION? 17

Fiscal Federalism 17

Fiscal Decentralisation 17

THE NEED FOR FISCAL DECENTRALISATION IN ZAMBIA 17

FISCAL DECENTRALISATION CONCEPTS 18

Finance Follows Function 18

Informed Public Opinion 19

Mechanisms for Articulating Local Priorities 19

Adherence to Local Priorities 19

Incentives for Participation 19

Local Government Fiscal Responsibility 19

Instruments to Support Decentralisation 20

ISSUES FOR CONSIDERATION 20

Vertical Imbalance 20

Horizontal imbalance 21

APPLYING THE CONCEPTS IN ZAMBIA 21

Instability of Expenditure Assignments 21

The Cost of Undertaking the Functions 21

Instability of Revenue Assignments 22

Current Status 22

CHAPTER 4 ELEMENTS OF FISCAL DECENTRALISATION 23

THE KEY ELEMENTS / PILLARS 23

Expenditure Assignments and Autonomy 23

Local Revenue Source Assignments and Autonomy 26

Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfers 27

Access to Capital Funds 28

THE ENABLING ENVIRONMENT 28

Policy Framework 28

Legal Framework 28

Locally Elected Councils 29

Locally Appointed Chief Ofcers 29

Fiscal Discipline 30

Political Accountability 30

SEQUENCING THE ELEMENTS 31

CHAPTER 5 FACTORS DETERMINING THE ALLOCATION OF FISCAL

RESOURCES AT DIFFERENT GOVERNMENT LEVELS 33

FISCAL RESOURCES 33

FISCAL CAPACITY 33

vi

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

Tax Base 33

Ability to Pay 34

Fiscal Effort 34

Tax Burden 34

POLITICAL WILL 34

THE NEED FOR A STRONG CG 34

CHAPTER 6 LOCAL AND MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT

FUNCTIONS AND EXPENDITURES 37

LEGAL PROVISIONS 37

FUNCTIONS CURRENTLY UNDERTAKEN 37

SHARED FUNCTIONS 38

ISSUES TO RESOLVE 38

CHAPTER 7 LOCAL AND MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT REVENUES

AND SOURCES 39

INTERNATIONAL DECLARATIONS ON LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE 39

LG REVENUES IN ZAMBIA 40

LOCAL TAXES 40

Rates 40

Personal Levy 41

Business Levies 42

OTHER LOCAL REVENUE SOURCES 42

Fees and User Charges 42

Business Licenses 43

CAPITAL FUNDS 43

CHAPTER 8 INTERGOVERNMENTAL FINANCIAL

RELATIONS AND TRANSFERS 45

THE TRANSFERS 45

Trends and Values 45

Comparisons 48

THE INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL ARCHITECTURE (IFA) 48

Restructuring Grant 48

Recurrent Grant 49

Capital Grant 49

Devolution Grant 49

ISSUES WITH IFA 50

vii

CHAPTER 9 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 51

The Decentralisation Process 51

LESSONS LEARNED 51

Lessons to be relearned from the DDPI 51

Decentralisation Indicators 52

Sequencing 52

Service level determination 52

The role of CG 52

RECOMMENDATIONS 52

Lessons to be relearned from the DDPI 52

Decentralisation Indicators 52

Sequencing 52

Service level determination 53

The role of CG 53

APPENDICES 55

Appendix 1: Works Cited 55

Appendix 2: Zambia Exchange Rates and Inflation 59

Appendix 3: GRZ Budget 2012: Address to Parliament 60

Appendix 4: Bank of Zambia Policy Rate Announcement 61

Appendix 5: District Population and Budgets 2007 63

Appendix 6: Sources of revenue – Lusaka City Council 66

Appendix 7: Required Services and Ranking 67

viii

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

Abbreviation Full Term (extra information)

ADC Area Development Committees

ADZ Area Development Zone

AG Auditor General

Cap Chapter (usually in references to the Laws of Zambia)

CDF Constituency Development Fund

CG Central Government

CRC Constitution Review Commission

CRCs Core Recurrent Costs

DDCC District Development Coordinating Committees

DDPI District Development Planning and Implementation

DIP Decentralisation Implementation Plan

DP Decentralisation Policy

ERC Electoral Reform Committee

FD Fiscal Decentralisation

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GFS Government Financial Statistics

GRZ Government of the Republic of Zambia

HR Human Resource

IFA Intergovernmental Fiscal Architecture

IGT Intergovernmental Transfer (Grants)

IMF International Monetary Fund

JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency

LED Local Economic Development

LG Local Government

LGAZ Local Government Association of Zambia

LGSC Local Government Service Commission

LuSE Lusaka Stock Exchange

MCRC Mung’omba Constitution Review Commission

MLGELE Ministry of Local Government, Early Learning and Environment (until October 2011 for-

merly; Ministry of Local Government and Housing)

ix

MLGH Ministry of Local Government and Housing (October 2011, renamed Ministry of Local

Government, Early Learning and Environment)

MoFNP Ministry of Finance and National Planning

MTEF Medium Term Expenditure Framework

NDCC National Development Coordinating Committee

OOR Optimized Own Resources

PAYE Pay As You Earn

PDCC Provincial Development Coordinating Committee

PKSOI U.S. Army Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute

PPP Public Private Partnership

PSRP Public Sector Reform Programme

RTC Road Trafc Commission

SNDP Sixth National Development Plan

ToR Terms of Reference

US $ United States Dollar

VFG Vertical Fiscal Gap

VFI Vertical Fiscal Imbalance

ZDA Zambia Development Agency

ZESCO Zambia Electricity Supply Corporation

ZICA Zambia Institute of Chartered Accountants

ZMK Zambian Kwacha (Zambian currency)

x

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

LISTS OF FIGURES, GRAPHS, MAPS AND TABLES

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1-1: Population Distribution 1990 - 2010 3

Table 1-2: District Types, Population and Budgets 4

Table 1-3: Zambian Government Expenditure

Relative to GDP (World Bank Data) 9

Table 1-4: Decentralization Indicators for Developing

and Transition Economies 9

Table 1-5: Zambia’s Fiscal Decentralisation Indicators 1976 – 1980 10

Table 1-6: Countries Reporting Decentralisation Statistics in GFS 10

Table 1-7: Zambian Decentralisation Performance 11

Table 1-8: Zambian Indicator Progress towards Maximum Benchmarks 12

Table 2-1: Performance of Council Revenue Sources -2006 16

Table 4-1: Expenditure Responsibilities 24

Table 4-2: Population Densities Mpika and Monze 25

Table 4-3: Per Capita Revenue Budgets for Cities 25

Table 4-4: CG and LG Tax Bases 27

Table 4-5: Sequence Steps and the DIP Components 32

Table 5-1: Emerging Governance Structure (from (Sharma, 2003, p. 183) 35

Table 7-1: Revenue Composition 2006 40

Table 7-2: Valuation Roll Arrears 41

Table 7-3: GRZ Budget for MLGH Loans 2006 – 2012 (US $ 000) 44

Table 8-1: Total GRZ Expenditure and Budgeted Intergovernmental

Transfers 2002 – 2011 (US $ Million) 45

Table 8-2: National Support as Percentage of Total Council Revenue 47

Table 8-3: National Support (source (JICA, 2007) 47

Table 8-4: Composition of IGTs 2010 - 2012 (US $ ) 49

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1-1: Government Administrative Levels 1

Figure 1-2: Administrative Structure of

Central and Sub-National Governments 2

Figure 1-3: Zambian Indicators – Maximum Attainment 12

Figure 3-1: Trends in IGTs 2002 - 2011 22

Figure 4-1: Sequencing Fiscal Decentralisation

(Adapted from Bahl & Martinez-Vazquez (2006, p. 4)) 32

Figure 8-1: IGTs as Percent of GRZ Expenditure 46

1

CHAPTER 1

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF ZAMBIA

CHAPTER 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN THE

CONTEXT OF ZAMBIA

Zambia is a unitary state, the Government

of the Republic of Zambia (GRZ), with two

levels of government; Central and Local.

e provincial level is in reality a part of the

Central Government as it has no separate

legal framework, assigned expenditure or

revenue raising assignments to dierentiate

it from the Central Government. Zambia

attained political independence from the

British in 1964. While at the local level, Local

Authorities (referred to collectively as Councils

in this document) have some responsibilities

for service provision, Central Government

(CG) also has oces at that level to provide

other services.

e Local Government Association of

Zambia (LGAZ) provides, in the Councillors

Orientation Manual (MLGH-LGAZ, 2006),

an interesting history of pre-colonial, pre-

independence and post-independence

local governance in Zambia. For purposes

of discussing Fiscal Decentralisation (FD)

in Zambia, a brief history of the post-

independence developments in local

governance is outlined in this section.

Administrative Structure and

Functions

While Zambia has two levels of government,

Central and Local, it has four administrative

levels for delivering government services as

shown in Figure 1-1.

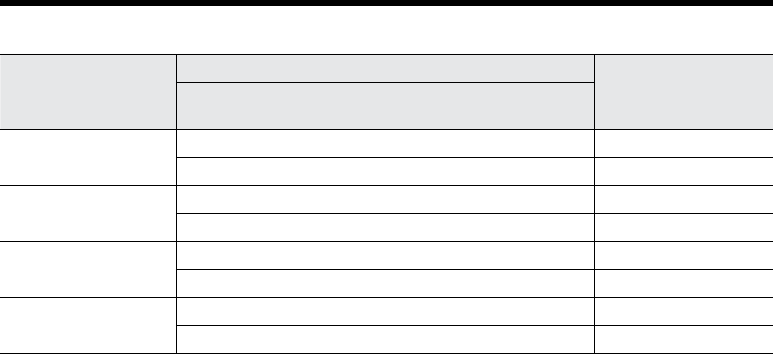

FIGURE 1-1: Government Administrative Levels

Central Local

Institution Policy Head Executive

Head

Institution Policy Head Executive

Head

National Cabinet Republican

President

Secretary to

the Cabinet

Line Ministries Minister Permanent

Secretary

Provincial Provincial

Administration

Provincial

Minister

Permanent

Secretary

District District

Administration

District

commissioner

City and Municipal

Councils

Mayor Town Clerk

District

Councils

Chairman Council

Secretary

Sub District Wards Councilor

Source: Own depiction.

2

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

Professor Saasa (Saasa & Others, 1999, p. 65) adds co-ordinating organisations to his depiction

of the administrative structures of the Zambian government as shown in Figure 1-2.

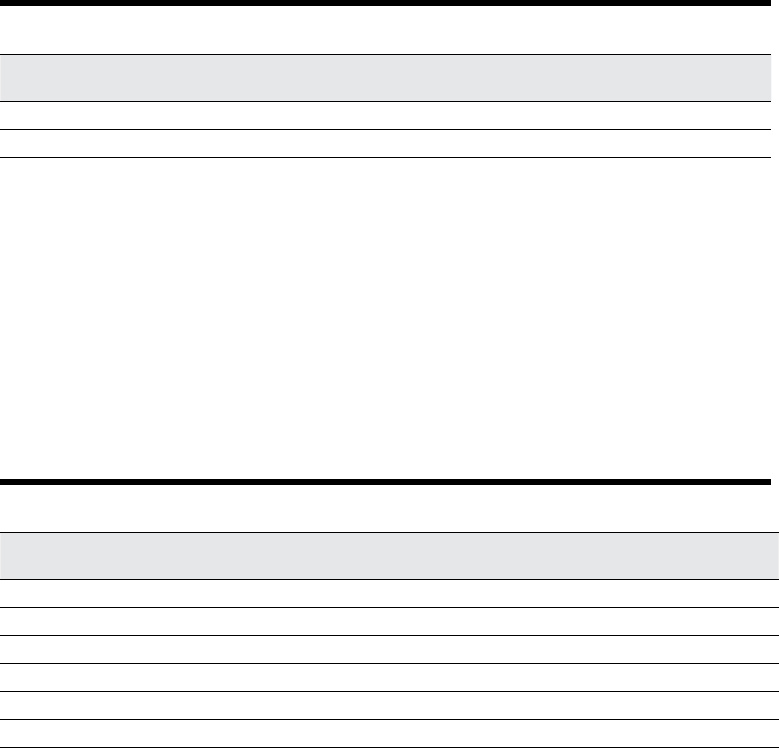

FIGURE 1-2: Administrative Structure of Central and Sub-National Governments

Level Administrative Decentralised Deconcentrated &

Semi-autonomous

Co-ordinating

Bodies

NATIONAL Secretary to

the Cabinet

Line Ministries

NDCC

PROVINCE Provincial

Permanent

Secretary

Provincial

Departmental

Head

PDCC

(Chaired by Provincial

Permanent Secretary)

DISTRICT Line Ministry Ofcials Councils Health Boards

Education

Management Boards

DDCC

Chaired by Town Clerk

or Council Secretary

Source: (gure 3.2 (Saasa & Others, 1999, p. 65))

e functions of the dierent administrative

levels of government, as articulated in Chapter

2 of the National Decentralisation Policy

(GRZ - Cabinet Oce, 2002, p. 8) are

outlined below.

Central Government

National Level Institutions

At national level, there exists the Cabinet

Oce, which is responsible for the

management and coordination of the Public

Service. e Secretary to the Cabinet is

head of Government Administration, which

comprises sector Ministries and statutory

bodies, Provincial and District administration.

In order to enhance the operations at National

level, Cabinet Oce is expected to coordinate

development activities through the National

Development Coordinating Committee

(NDCC).

Provincial Level Institutions

At each Provincial level, there is the Provincial

Administration Headquarters headed by a

Deputy Minister assisted by a Permanent

Secretary responsible for the coordination of

Government business in the Province. Apart

from this oce, there are Provincial Heads

of Departments through whom functions of

sector Ministries are carried out. Provincial

Heads of Departments are answerable to

3

CHAPTER 1

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF ZAMBIA

their respective Sector Ministries on technical

matters but administratively supervised by the

Permanent Secretaries for the Province on day-

to-day administration.

To enhance the operations of the Provincial

Administration, Government through

Circulars has established the Provincial

Development Coordinating Committee

(PDCC) as a forum for coordinating the

planning, implementation and monitoring of

development activities at the Provincial level.

e PDCC is, however, ineective because its

creation and existence is not backed by any legal

framework. Equally, the Permanent Secretaries

of the Provinces, who are the chairpersons of

the PDCC, have no legal powers to supervise

and discipline sector ministry personnel.

District Level Institutions

At the District level, there is District

Administration headed by a District

Commissioner, appointed by the Republican

President, who is responsible for coordinating

developmental activities. District

Administration comprises various sector

Ministerial departments performing specied

Government functions and responsible for

implementing programmes and report to their

respective Provincial heads of department. In

order to enhance the operations of District

Administration, Government through

Circulars established DDCC as a forum for

coordinating the planning and implementation

of development activities at the District level.

e District Development Coordinating

Committee is ineective because no legal

framework backs its operations. Town Clerks

and Council Secretaries who, until the

appointment of District Commissioners,

were chairing the DDCCs had no legal

backing to supervise and discipline sector

Ministry personnel operating at the District

level. In addition, there are semi-autonomous

institutions of local governance, such as,

Health and Education Management Boards

created to perform specied functions on

behalf of sector Ministries aimed at increasing

community participation in the planning and

delivery of services.

Local Government

District Level Institutions

“As regards local Government, there is

a single-tier system of local government

comprising three types of councils, namely:

City, Municipal and District Councils

responsible for the provision of services”

(GRZ - Cabinet Oce, 2002, p. 9). Until

2011, Zambia had 9 provinces and 72 councils.

e councils were made of 4 City Councils, 14

Municipal Councils and 54 District Councils.

eir populations as per 1990, 2000 and 2010

census are given in Table 1-1.

TABLE 1-1: Population Distribution 1990 - 2010

Type # Councils

1990

Census

1990

Percent

2000

Census

2000

Percent

2010 Census

2010

Percent

City 4 1,526,645 19.68% 1,938,872 19.61% 2,862,299 21.94%

Municipal 14 2,021,327 26.05% 2,425,728 24.54% 2,958,714 22.68%

District 54 4,211,145 54.27% 5,520,991 55.85% 7,225,495 55.38%

Grand Total 72 7,759,117 100.00% 9,885,591 100.00% 13,046,508 100.00%

Source: 1990, 2000 & 2010 Census of Zambia

4

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

In early 2011 the government created an

additional district, Manga. In 2012, as part

of the process of decentralising the government

administration and getting the government

closer to the people, the government has,

since its election in September 2011, created

an additional province, Muchinga, and 5

additional district councils (Chikankata,

Chirundu, Mulobezi, Nsama and Chilanga)

bring the totals to 10 provinces and 78

councils.

e second schedule (section 61), of the

Local Government Act Cap 281 prescribes

sixty-three (63) functions to be performed

by all Councils regardless of their status and

capacity. e sixty three functions, some of

which have sub-functions, are all discretionary

as section 61 states “Subject to the provisions

of this Act, a council may discharge all or

any if the functions set out in the Second

Schedule”.

e assignment of the sixty-three functions

listed under the Act without taking into

account capacity, results in Councils not

performing to the satisfaction of their local

communities. Although councils are bodies

Corporate, they also perform delegated

functions of the Central Government.

e Mayor/Council Chairperson is a

political head of the Council and, performs

ceremonial functions. However, there is a weak

link between the Mayor/Council Chairperson

and the Ministry of Local Government

and Housing which has led to lack of co-

ordination, transparency and accountability

on civic matters.

Sub-District Level Institutions

ere are wards, which are sub-structures

of the councils at sub-district level for the

purposes of Local Government Elections

only. e Registration and Development

of Villages Act establishes the Ward

Development Committees and Village

Productivity Committees in each ward as a

forum for community participation in local

development activities and aairs. However,

these institutions are not linked to Local

Government and are no longer functional in

most districts. is has led to lack of forum for

community participation in decision-making

on their local development activities and

aairs at sub-district level.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Constitutional Provisions

Before the Constitution Amendment Act

No. 18 of 1996 came into force, there were no

constitutional references to Local Government

in Zambia. e country could therefore have

been administered without local government

up to then.

TABLE 1-2: District Types, Population and Budgets

Type # Districts Pop 2007 Revenue Budget

Average Per

District

Per

Capita

City 4 2,585,271 $44,084,651 $11,021,163 $20.86

Municipal 14 2,798,817 $29,500,457 $2,107,175 $12.36

District 54 6,714,144 $20,910,983 $387,240 $3.47

Grand Total 72 12,098,232 $94,496,091 $1,312,446 $6.17

Summarised from Appendix 5, 2007 population interpolated between 2000 and 2010.

e 2007 council revenue budgets per type of district are given in Table 1-2.

5

CHAPTER 1

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF ZAMBIA

Article 109 of Part VIII of the 1996

Constitution provides that “ere shall be

such system of Local Government in Zambia

as may be prescribed by an Act of Parliament.

e System of Local Government shall be

based on democratically elected Council on

the Basis of universal surage.”

e Mung’omba Constitution Review

Commission (MCRC), appointed in June

2003, in its report, the Report Of e

Constitution Review Commission (MCRC,

2005, p. 402) stated, in respect to the above

constitutional provision that: “What this

means is that the local government system in

Zambia has been left to operate within the

provisions of an Act of Parliament (Local

Government Act Cap. 281 of the Laws

Zambia), which could be changed at will to

suit a given political situation. e present

Act has many weaknesses. For example:

• the Act does not expressly dene the purpose

and objectives of local government;

• in terms of service delivery, the Act does

not set minimum standards for measuring

performance in Councils;

• since governance transcends the State and its

organs to include civil society, the Act does

not dene relationships between various

stakeholders in local governance, that is, the

Act does not provide for decentralisation or

co-operative governance at all;

• the Act leaves out the all-important aspect

of local government nance in terms of

scal relations between Central and Local

Government;

• the Act also gives the Minister so many powers

over democratically elected councils that he

or she can legally suspend all councillors and,

with the approval of the President, dissolve

all the councils and administer the whole

country with appointed local government

administrators; and

• the Act makes no reference to Provincial

Administration or how the councils will

relate with the province.

Statutory Provisions

Since becoming independent, Zambia

has implemented three Local Government

Reforms in which the legal framework for

Local Government (LG) has been modied.

The Local Government Act - 1965 - 1980

Councils operated under the Local

Government Act of 1965 from 1965 to 1980.

e Act came into eect on 1st November,

1965. is Act provided for a system of local

government in a multi-party environment. It

provided for councillors elected by universal

adult surage with Mayors and Council

Chairmen elected by fellow councillors. It also

provided for four categories of councils; City,

Municipal, District and Rural.

Under the Local Government Act of 1965,

the operations of councils could be further

split into two sub-phases. e period 1965

to 1973 was a period of great successes in

local government. During this period local

councils operated electricity and water supply

and sanitation services and, according to the

National Decentralisation Policy, (GRZ -

Cabinet Oce, 2002, p. 14), “70% percent of

the income of Councils came from the Central

Government through the Ministry of Local

Government and Housing as grants, while 30%

was met by revenue raised from local levies, fees

and charges as well as specied funds from other

Sector Ministries whose functions they performed”.

is enabled councils to plan and implement

adequate service delivery programmes.

During the period 1973 to 1980 the nancial

bases of councils began to deteriorate directly

as a result of CG decisions. e withdrawal

of the housing grant in 1973, police grant,

health grant and re grant, among others; the

1974 Rent (Amendment) Act which restricted

councils from evicting defaulting tenants

6

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

(until after accruing arrears in excess of three

months); the declaration that undeveloped

land had no value and was not rateable;

the transfer of electricity distribution from

Councils to the Zambia Electricity Supply

Corporation (ZESCO), without transferring

the liabilities that related to those services; and

the withdrawal of long term capital funding all

impacted negatively on the councils’ abilities

to deliver service.

Local Administration Act 1980 - 1991

Councils operated under the Local

Administration Act No. 15 of 1980 from 1980

to 1991. Under this Act, which operated under

the one party state, party and government

functions were merged and additional oces

created in councils without additional

nancing. Ward Chairmen, elected during the

single party elections, became the councillors

and the District Governors, appointed by the

Republican President became the Chairmen of

Councils.

Some CG functions were transferred to LG

without nance following these functions.

ese included registration of villages,

construction of feeder roads and water supply

schemes according to the Decentralisation

Policy (GRZ - Cabinet Oce, 2002, p. 4),

thereby further deteriorating service provision.

Local Government Act 1991 to date

After returning to multi-party politics in

1991 the Local Government Act (Cap 281) of

1991 replaced the Local Administration Act

of 1980. is Act was substantially a return

to the Local Government Act of 1965. Under

this Act, the operations of councils can also be

split into two sub-phases. During the period

1991 to 2001 various CG policies and pieces

of legislation were passed that either reduced

the revenue bases of councils or imposed

additional expenditure on councils.

ese included the following: e complete

withdrawal of government grants to Councils

announced in the 1992 national budget

speech. Ironically that budget was itself only

balanced by inclusion of grants to the Central

Government by various bi-lateral and multi-

lateral partners; the 1993 transfer of motor

vehicle licensing functions from Councils to

the Road Trac Commission (RTC) while the

responsibility to maintain the roads remained

with the council; the Presidential directive for

sale of council and parastatal housing units

to sitting tenants in 1996 at below market

prices thereby wiping out rental income from

the council revenue bases; the rating Act No.

12 of 1997 which increased the categories of

properties exempt from paying rates (this was

reversed in 1999 but councils had still lost

substantial income).

In addition, water supply and sanitation

undertakings were transferred from councils

to commercial utilities, wholly owned by

councils, under Statutory Instrument No. 55

of 2000, without transfer of related liabilities;

the Local Authorities Superannuation Fund

(Amendment) No. 27 of 1991 which made

it mandatory for council employees who had

spent 22 years in service of Councils to retire

but did not provide for the resulting terminal

payments to retiring employees. is also had a

negative impact on the operational capacities of

councils as key expertise was lost; and granting

of backdated 50 percent salary increments to

unionised council employees just before the

2001 elections without providing the required

nancial resources to cover those increments.

During the period 2001 to date several

positive CG policies and pieces of legislation

have been passed that reverse some of the

negative trends of the previous 27 years. ese

include: the reverting of management of bus

stations and collection of market levies to

councils through the Markets and Bus Stations

Act No 7 of 2007; the appointment of Local

Government Practitioners on the Constitution

Review Commission (CRC) and the Electoral

Reform Committee (ERC); the extension of

councillors tenure of oce from three to ve

7

CHAPTER 1

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF ZAMBIA

years; the protection of council property from

seizure by court bailis; the enactment of the

Market and Bus Stations Act; the resumption

of capital and recurrent grant to councils; the

approval of the Decentralization Policy (DP);

and the formulation of the Decentralisation

Implementation Plan (DIP).

One of the Terms of Reference (ToR) of the

2003 MCRC Commission was to “…examine

the local government system and recommend

how a democratic system of local government

as specied in the constitution maybe realized”.

According to Simwinga (a Constitution Review

Commissioner and Former Town Clerk of

Kitwe City Council) in “Local Government in

Zambia: Issues Relevant to the Constitution

Making Process” (Simwinga, 2007, p. 16),;

“e Commission received an overwhelming

3,799 submissions on Local Government alone.

Most of the petitioners called for the devolution

of power and the transfer of the resources from

central government to Local Authorities”. In

response to this, the Constitution Review

Commission (CRC, 2005a) provided in Part

XII of their Draft Constitution 28 Articles,

articles 230 to 257, dealing with Local

Government. e Constitution of Zambia

Bill presented to Parliament in 2010 (NCC,

2010) had 13 Articles from 212 to 224 dealing

with Local Government. e Bill was rejected

by Parliament as not representing the peoples

will.

Zambia’s fth Republican President, elected

into oce in September 2011, His Excellency

Michael Chilufya Sata in his inaugural speech to

Parliament on 14

th

October 2011 said, relating

to scal decentralisation, “Our government will

also devise an appropriate formula for sharing

national taxes collected at the centre within the

jurisdiction of every local authority in order to

strengthen their revenue base and ensure that

all government grants are remitted on time.”

(Zambian Economist, 2011). In the 2012

Budget Address to Parliament (Scribd, 2011,

p. 9) on 11

th

November 2011, the Minister

of Finance and National Planning Hon.

Alexander Chikwanda MP, stated that “in

2012, I have increased the grants to councils by

more than 100 percent to ZMK K257.1 billion

(US $ 75.4 million)” ese statements seem

to be a continuation of the positive trends in

local government during this phase.

DECENTRALISATION

e Public Sector Reform Programme

(PSRP) launched in 1993 has three

components: Restructuring the Public

Service; Management and Human Resources

Improvement; and Decentralization and

Strengthening Local Government. Zambia’s

Vision 2030 (GRZ, 2006) which sets out

the long term aspirations of Zambia includes

the aspiration for “Decentralized governance

systems”. e Sixth National Development

Plan (SNDP) 2011 – 2015 (GRZ, 2011) one

of the tools for implementing the Vision 2030

states “In line with the goal to decentralise service

delivery functions to the councils, focus will be

on the implementation of the Decentralisation

Implementation Plan (DIP). In the medium-

term the Government will focus on building the

necessary capacity of the councils to prepare them

to carry out the devolved functions”. us the

theme of decentralisation runs through various

government pronouncements and policies.

Justication

According to the DIP (MLGH, 2006,

p. 5) “the most fundamental rationale for

decentralisation in Zambia lies in its opportunity

to bring the government closer to the people by

providing citizens with greater control over the

decision making process and allowing their direct

participation in public service delivery” e

DIP has now been revised (MLGH, 2010) but

essentially has the same content.

is rationale, together with the possibility

of improving the eectiveness of public

expenditure by targeting needs identied

by the communities, runs through all the

8

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

government policies and pronouncements

that relate to decentralisation.

Decentralised Development Planning

As part of the preparation for addressing the

Decentralisation pillar of the PSRP, Zambia

undertook a decentralised planning pilot

project the “District Development Planning and

Implementation in Eastern Province” (DDPI)

from 1996 to 2001. is project covered

all the eight districts in the province and its

immediate objectives were:

1. MLGH uses lessons learned from Eastern

Province for national decentralization

policy and implementation process.

2. Stakeholders involved in District

development produce and maintain

sustainable infrastructure using

decentralized scal transfers of

discretionary and conditional grants,

participatory development planning and

localized production arrangements in

Eastern Province.

3. Local government demonstrates eective

and responsive leadership and facilitation

of the development process.

Even though, according to the project’s

terminal evaluation report (Rwampororo,

Tournee, & Chitembo, 2002), “the project

increased capacity for service delivery of District

Council sta, Councillors, District Development

Coordinating Committees (DDCC) members

and other relevant stakeholder groups in order

for them to understand and perform their roles

better” the upscaling of lessons learned has not

been possible as the underlying decentralised

governance system has not been put in place

to date.

Situation to Date

Zambia’s Decentralisation Policy (GRZ

- Cabinet Oce, 2002) was approved in

2002 and ocially launched in 2004. e

Decentralisation Implementation Plan (DIP)

2006-2010 (MLGH, 2006) revised to cover

2009 – 2013 (MLGH, 2010) was developed

in 2006 and approved in 2010. In 2006

Zambia, with the participation of various

cooperating partners led by the World Bank,

embarked on developing and implementing

a Local Development program (LDP) aimed

at operationalizing the DIP. rough its

preparatory process the LDP developed

and agreed on various principles in the

operationalization of the DIP including the

required Intergovernmental Fiscal Architecture

(IFA) to address the scal relations of a

decentralised governance system.

e delay in GRZ formally approving the

DIP led to some cooperating partners, such

as the World Bank, shifting the focus of their

cooperation away from decentralisation to

other activities. Despite this, some aspects

of the IFA have been implemented and are

discussed in Chapter 8.

PUBLIC EXPENDITURE RELATIVE TO

GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT

Public expenditure as percentage of Gross

Domestic Product (GDP) gives an indication

of the size of the public sector in an economy.

e World Bank data (World Bank, 2011) for

Zambian GDP and government expenditure

as a percentage of GDP for Zambia and

averages for Africa are are given in Table 1-3.

9

CHAPTER 1

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF ZAMBIA

ese data show moderate public sector

expenditure in the economy. Similar “ratios for

Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda are, respectively,

24.1 per cent (1995), 28.7 per cent (1995) and

18.1 per cent (1996)” (Smoke, 2001, p. 9)),

it would therefore seem that in this regard,

Zambia is within the norm.

FISCAL DECENTRALISATION

INDICATORS and PERFORMANCE

Global Indicators and Ranges

Anwar Shah (Shah, 2004, p. 15) provides

various indicators for decentralisation and

calculates ranges from IMF and World Bank

data. ese indicators and their ranges are

given in Table 1-4

TABLE 1-3: Zambian Government Expenditure Relative to GDP (World Bank Data)

1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

GDP US $ Million 3,237.20 3,131.34 3,237.72 3,636.94 3,716.09 4,373.86

Zambia ((Govt exp x 100)/GDP) 21.4303 17.4303 - 15.8781 15.9944 17.6443

Africa ((Govt exp x 100)/GDP) - - - - - -

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

GDP US $ Million 5,423.20 7,156.85 10,675.37 11,410.06 14,381.87

Zambia ((Govt exp x 100)/GDP) 20.0127 23.0007 17.0112 22.9420 -

Africa ((Govt exp x 100)/GDP) 24.8842 24.9347 25.5451 25.3162 26.3082

Source: (World Bank, 2011) (ADI.xlsx) GDP Series: NY.GDP.MKTP.CD; ((Govt exp x 100)/GDP) Series: GC.XPN.

TOTL.GD.ZS

TABLE 1-4: Decentralization Indicators for Developing and Transition Economies

Transition (1999 Developing (1997

Average Max Min Average Max Min

Sub-national Expenditures

As % GDP 10.8 20.4 5.8 7.4 18.3 0.8

As % of public sector expenditures 22.3 38.8 7.3 23.3 45.2 3.5

Sub-Nat 1 education expenditures, as % public sector education

expenditures

55.9 91.4 0.2 49.8 97.5 0.2

Sub-Nat 1 health exp.. as % of public sector health expenditure 41.9 95.9 0.3 60.2 98.1 13.7

Sub-national revenues

As % of GDP 7.9 17.1 2.9 5.3 12.5 0.5

As % of public sector revenues 18.4 36.0 5.6 16.6 39.8 2.2

Fiscal transfers

As % of sub-national revenues 24.0 50.4 4.1 42.2 80.8 5.0

Sub-national autonomy

Tax autonomy 55.1 91.0 29.1 40.1 76.5 7.6

Expenditure autonomy 74.0 96.2 49.6 58.0 95.0 23.4

Source: (Shah, 2004, p. 15)

10

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

LG expenditure as a percentage of public

expenditure, that is expenditure of all levels

of government, is often used as a proxy

for the degree of scal decentralisation as

indicated in Table 14. Smoke (Smoke, 2001,

p. 10), indicates this gure at 43.5 percent for

Ethiopia (1996), 21 percent for Uganda (1995)

and “only” 4.2 percent for Kenya (1995). All

these are within the ranges provided by Shah

in Table 14 of maximum of 45.2%, average of

23.3% and a minimum of 3.5%.

1. The Zambian Indicators

e World Bank (World Bank, 2001b)

provides various indicators of scal

decentralisation for Zambia for the period

1976 to 1980. ese are summarised in Table

1-5.

TABLE 1-5: Zambia’s Fiscal Decentralisation Indicators 1976 – 1980

Indicator 1980 1979 1978 1977 1976

Sub-national expenditures (% of GDP) 1.62 1.68 2.19 2.02 1.50

Sub-national Expenditures (% of total expenditures) 4.19 5.23 6.87 5.39 3.98

Sub-national revenues (% of GDP) 1.35 1.41 1.35 1.58 1.51

Sub-national Revenues (% of total revenues) 5.13 5.94 5.19 5.91 5.94

Fiscal Transfers (% of total sub-national revenues) 34.08 27.75 26.92 31.21 3.05

General Public Services (% of total sub-national expenditures) 46.28 47.43 44.62 29.35 23.59

Vertical Imbalance (%) 43.06 32.21 22.72 35.32 3.17

Source: Extracted from (World Bank, 2001b)

More recent data are not readily available

for decentralisation indicators in Zambia. In

some instances this is not peculiar to Zambia.

For instance regarding the indicator for

total annual Local Government Revenue or

Expenditure the World Bank notes that: “While

the framework for the GFS (IMF Government

Financial Statistics) is very comprehensive,

available data are much less comprehensive

when analyzing decentralization. For instance,

only 46 countries reported expenditures at both

the national and subnational level in 1996”

(World Bank, 2001). It is feasible that some

the countries that might not have reported

could have this information locally. e

breakdown of countries reporting indicators

for decentralization in the GFS is shown in

Table 1-6.

TABLE 1-6: Countries Reporting

Decentralisation Statistics in GFS

Levels of Reporting Number of Countries

Central and Local 32

Central and Provincial 2

Central, Provincial and Local 12

Total 46

Source: (World Bank, 2001)

11

CHAPTER 1

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN THE CONTEXT OF ZAMBIA

The Zambian Performance

is section looks at the Zambian

decentralisation performance by comparing

the Zambian indicators to the established

indicator ranges.

e “International Monetary Fund (IMF):

Government Finance Statistics Yearbook”

(IMF, 2008, p. 487) has both Zambia’s CG

and LG budgeted revenue for 2005. e CG

revenue gure was ZMK 7,973.90 Billion

($1,992,229,856) while the LG gure was

ZMK 92.7Billion ($23,160,525). is

indicates that for 2005, LG revenues were less

than 1.5% of general government revenues.

e above IMF data series has the Zambian

Central Government revenue and expenditure

budget amounts for three years, 2005 – 2007,

but has no Local Government revenue data for

2006 or 2007. Using the Local Government

budgeted revenue of ZMK378.22 Billion

($94,496,091) from Appendix 5, the IMF

Central Government expenditure for 2007

of ZMK 10,094.6 Billion ($2,522,073,704)

(IMF, 2008, p. 487), would imply, even though

there might be slight dierences in denitions

of revenue, that local government revenues

were about 3.6% of total public revenues.

Relating the LG revenues of 2005 and 2007

to the Zambian GDP of $13,228,627,361

and $15,932,984,420, respectively, the LG

revenues were found to be 0.16% and 0.59%

of the 2005 and 2007 GDPs, respectively.

e table below compares various Zambian

performance indicators, for specied years,

against the Shah benchmarks.

TABLE 1-7: Zambian Decentralisation Performance

Indicator

Benchmarks Zambian Performance

Min. Avg. Max. 2007 2005 1980 1979 1978 1977 1976

Sub-national expenditures (% of GDP) 0.8 7.4 18.3 1.62 1.68 2.19 2.02 1.5

Sub-national Expenditures

(% of total expenditures)

3.5 23.3 45.2 4.19 5.23 6.87 5.39 3.98

Sub-national revenues (% of GDP) 0.5 5.3 12.5 0.59 0.16 1.35 1.41 1.35 1.58 1.51

Sub-national Revenues

(% of total revenues)

2.2 16.6 39.8 3.6 1.5 5.13 5.94 5.19 5.91 5.94

Fiscal Transfers

(% of total sub-national revenues)

5 42.2 80.8 34.08 27.75 26.92 31.21 3.05

It would seem therefore that relative

to the range by Shah, Zambia’s level of

decentralisation, as measured by LG revenues

relative to total public revenue, was below the

minimum of 2.2% in 2005 at 1.5% but this

improved to 3.6% in 2007, however, this was

still considerably below the average of 16.6%.

Zambia’s performance in the late 70’s was much

better averaging 5.62% from 1976 to 1980.

For the other indicators, the Zambian trends

are that they are just above the minimum for

each indicator. is indicates that is more

centralised that is the norm for developing

countries.

Using the minimum and maximum

benchmarks to be 0% and 100% respectively,

the status of each of the available Zambian

indicators along the above scale is given

in Table 1-8. .. e table shows that none

of the available indicators went above the

average, 50%, of the range and some of them,

the negative values, indicate that Zambia’s

performance in these was even below the

minimum standard.

12

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

TABLE 1-8: Zambian Indicator Progress towards Maximum Benchmarks

Indicator

Zambian Performance Towards Maximum Benchmark

2007 2005 1980 1979 1978 1977 1976

Sub-national expenditures (% of GDP) 4.7% 5.0% 7.9% 7.0% 4.0%

Sub-national Expenditures (% of total expenditures) 1.7% 4.1% 8.1% 4.5% 1.2%

Sub-national revenues (% of GDP) 0.8% -2.8% 7.1% 7.6% 7.1% 9.0% 8.4%

Sub-national Revenues (% of total revenues) 3.7% -1.9% 7.8% 9.9% 8.0% 9.9% 9.9%

Fiscal Transfers (% of total sub-national revenues) 38.4% 30.0% 28.9% 34.6% -2.6%

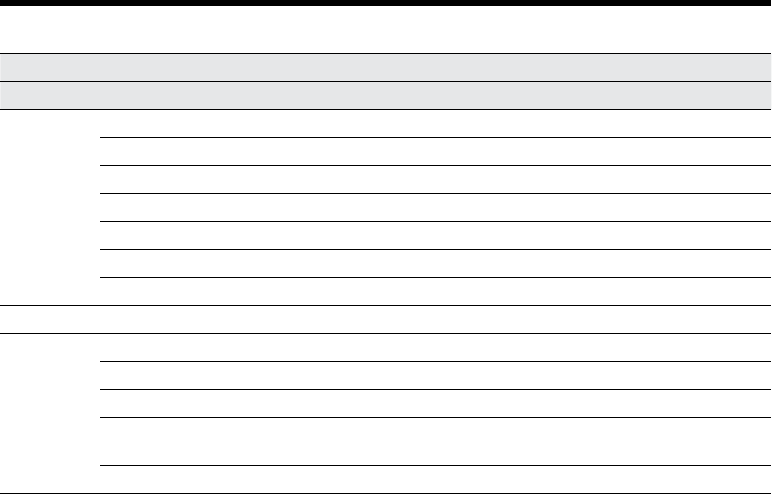

Figure 1-3 shows the maximum percentages ever achieved, for each of the ve indicators, in

relation to Shah’s ranges.

FIGURE 1-3: Zambian Indicators – Maximum Attainment

Maximum State Attained

38.4%

9.9%

9.0%

8.1%

7.9%

0.0%

Fiscal Transfers (% of total sub-national revenues)

Sub-national Revenues (% of total revenues)

Sub-national Revenues (% of GDP)

Sub-national Expenditures (% of total expenditures)

Sub-national Expenditures (% of GDP)

10.0% 20.0% 30.0% 40.0% 50.0%

Despite most of the data being from the

1970s, the data mined for 2005 and 2007 as

regards LG revenues conrms the downwards

trends from 1977 onwards. erefore, it is safe

to assume that, with the exception of Fiscal

Transfers, which seem to have stabilised in

the 30% percentage range, Zambia has been

centralising over the past three decades.

13

CHAPTER 2

OVERVIEW OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE

is chapter presents the concept of public

nance and its role in nancing the goods and

services described in Chapter 1. It describes the

characteristics of public nance, the market

justication for public nance and compares

and contrasts public nance to market based

nancial management disciplines such as

corporate nance. It then links the concept of

public nance to LG as a component of public

nance and outlines how the concepts outlined,

which form the theoretical framework for LG

nance generally, are applied in Zambia.

PUBLIC FINANCE

Public Finance is the area of nancial

management that has to do with the

mobilisation, stewardship and utilisation

of nancial resources for the provision of

public goods and services. It diers from

other specialisations in nancial management,

such as Corporate Finance or Securities and

Investments, as in those other specialisations

the markets, when functioning correctly,

are expected to regulate the interactions

between sellers and buyers. Both sellers and

buyers have a choice whether to transact

or not, hence the concept of willing buyer

and willing seller that underpins the market

concepts. Underlying the market concept is

the exclusivity of entitlement to the goods and

services exchanged, if one buys a pair of shoes

or pays for a haircut, they have exclusive right

to the goods or service acquired and those

particular goods or service are not available to

anybody else.

Public goods and services have two key

characteristics: Non-excludability, meaning

the cost of excluding non-payers from

enjoying the services may be prohibitive; and

Non-rivalry, meaning consumption by one

does not diminish consumption by others.

Such services include services like national

security and defence and street lights. So even

though individual choice can also be exercised,

to some extent, in the choice of public goods

and services, due to the non-exclusivity

and non-rivalry nature of public goods and

services, the market is unlikely to provide such

services even if there was demand for them as

the buyers would be unlikely to voluntarily

pay for services to which they would not have

exclusive rights. Financing the provision of

such goods and services is the realm of public

nance.

e provision of public goods and services

is mainly through taxes and therefore public

nance is the collection of nancial resources,

mainly through taxes, the stewardship of

those resources on behalf of the public and

the prudent expenditure of those resources to

supply the required public goods and services.

e justication for public nance is that it

can, through appropriate policies, contribute

to the ecient allocation, equitable

distribution of the goods and services and to

the stabilisation of the economy (Musgrave,

2004)..

Allocation

Since public goods and services are non-

exclusive, and therefore benet all consumers,

whether they have paid or not, people will

not voluntarily directly pay for such services

to which they do not have exclusive rights. If

such services are not paid for then they cannot

CHAPTER 2 OVERVIEW OF LOCAL

GOVERNMENT FINANCE

14

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

be provided; no roads, no street lights and no

national security.

us for public goods and services the

ballot box becomes the proxy for the market

mechanism for allocating goods and services

as voters “will nd it in their interest to vote

such that the outcome will fall closer to their own

preferences” (Musgrave, 2004, p. 8).. us it

becomes the responsibility of the government

elected on the platform of providing a specic

bundle of goods and services to nd the

mechanisms to do so irrespective of whether

such goods and services are produced by the

government or the private sector.

Distribution

How the public goods and services can be

distributed equitably among the beneciaries

is a matter for consideration in public nance.

Whereas public goods and services are non-

exclusive, and therefore everybody is free to

enjoy them, the spatial distribution of these

goods and services may create conditions that

may exclude some from the ability to enjoy

them. e benets of street lights in one

neighbourhood may not necessarily equally

accrue to residents of another neighbourhood.

Spatial considerations may also mean that

street lights may be a key priority in one

neighbourhood but not in another. Public

policy and public nance can be tools for

dealing with the equitable distribution of

public goods and services.

Stabilisation

Public policy and public nance can be tools

for macro-economic stability targeting such

issues as unemployment, ination, foreign

exchange rates and economic growth through

the use of scal and monetary policies.

“Stabilization of the economy is a prerequisite

for economic growth” (PKSOI, 2009, p. 135),

see also (Ocampo, 2005) “Macroeconomic

stabilization policy can be broadly summarized

as methods to mitigate short-run business cycle

uctuations around some long-run growth path

using dierent policy instruments. Two policy

tools are often emphasized in the literature:

scal policy – the way that governments choose

aggregate expenditure and tax collection; and

monetary policy – the way central banks change

the amount of money supply via the price of

money – interest rates”. (Liu P. , 2010, p. 8).

In his address to the National Assembly

for the 2012 GRZ budget the Minister

of Finance and National Planning stated

“Mr. Speaker, macroeconomic policy under

the new administration will be geared

towards maintaining a stable macroeconomic

environment conducive to investment, inclusive

growth and employment creation” (GRZ -

MoFNP, 2011, p. 4). He set targets in respect

of GDP growth (7%), ination (7%), scal

decit (4.3% of GDP) and gross international

reserves (4 months import cover). He also

articulated the tools for achieving the targets;

limiting money supply growth, enhancing

eectiveness of monetary policy, maintaining

a exible exchange rate and nancial sector

regulatory framework. e budget extract

attached as Appendix 3 provides the rationale,

objectives and policy tools proposed to be

used by GRZ for achieving macro-economic

stability.

On 27

th

March 2012 the Bank of Zambia

announced that it would introduce a

benchmark interest rate called the Bank of

Zambia Policy Rate from the beginning

of April, see Appendix 4 for the full

announcement. On 30

th

March the Central

Bank News reported that “e Bank of Zambia

announced it would set its new monetary policy

benchmark interest rate at 9.00%. e move

marks a transition in the Bank’s monetary policy,

from money supply targeting to an interest rate

target system. e overnight lending facility rate

is due to be set at 250 basis points higher than the

policy rate. e new interest rate level represents

signicant tightening, and compares to previous

interest rate levels of around 6 percent. e

15

CHAPTER 2

OVERVIEW OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE

Bank of Zambia’s adoption of a monetary policy

benchmark interest rate follows similar moves by

Uganda and Angola last year.” (Central Bank

News, 2012).

LOCAL GOVERNMENT FINANCE AS

AN ASPECT OF PUBLIC FINANCE

Why Local Government Finance?

The issues

Given that public nance covers the

provision of public goods and services, it can

be assumed that it fully addresses the issues

related to LG nance which has to do with the

provision of public goods and services at the

local, rather than national, level. Except for

city states, this is only correct to some extent.

Since LGs operate within environments

created by CGs and both provide public goods

and services, issues arise regarding which

bundle of services are best provided by which

level of government (expenditure assignment),

which revenues are best collected by which

level of government (revenue assignment) and

how do these assignments of expenditures

and revenues match. With specic reference

to Zambia, the expenditure and revenue

assignments are discussed in Chapter 6 and

Chapter 7 respectively. Ensuring that LGs’

assigned responsibilities are commensurate

with their assigned resources is the central

theme of Fiscal Decentralisation.

Some goods and services are clearly best

suited to be provided by CG, National

Defence and Security for instance, others

are best suited to LG, street lights and refuse

removal, for instance. However, there are

several goods and services that are somewhat

less clear which is why LG setups are dierent

from country to country.

Definition

Local government nance “is about the

revenue and expenditure decisions of municipal

governments. It covers the sources of revenue

that are used by municipal governments – taxes

(property, income, sales, excise taxes), user fees,

and intergovernmental transfers. It includes

ways of nancing infrastructure through the

use of operating revenues and borrowing as well

as charges on developers and public-private

partnerships. Municipal nance also addresses

issues around expenditures at the local level and

the accountability for expenditure and revenue

decisions, including the municipal budgetary

process and nancial management”. (UN-

HABITAT, 2009, p. 1)

The Role of Local Government Finance in

Zambia

In reviewing the role of Local Government

nance in Zambia it is useful to use the public

nance context outlined earlier relating to the

contribution of public nance to the ecient

allocation, equitable distribution of the

goods and services and to the stabilisation of

the economy

Allocation

Zambia is a diverse country; from high

rainfall areas in the north to sandy almost

desert like areas in the west, from densely

populated areas in the urban centres to sparsely

populated areas in the rural areas. ere are

therefore considerable spatial variations in

demand for local public goods and services. It

would not be ecient for CG to provide these

area specic goods and services and therefore,

given a multi-level government system, as the

case is for Zambia, these area specic preferred

bundles of goods and services are better

provided by LG.

Distribution

Income inequalities in many places within

the same LG areas, urban and peri-urban areas

for instance, mean that some services, for

which basic access levels have been determined,

cannot be provided to all areas on the basis of

16

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

ability to pay. If, however, those services are

not provided they impact the whole LG area.

For Zambia, the case of cholera outbreaks is

a case in point. If proper water supply and

sanitation services are not provided for the

peri-urban areas, these outbreaks, even though

they may start in the peri-urban areas, can

quickly cross over to the urban cores of the

cities even if these are well served in terms of

water supply and sanitation.

LGs have the ability to cross-subsidise these

services by charging higher taris for the

higher consumption in the urban cores of the

LG areas and lower taris in the peri-urban

areas. ey also have the discretion to use the

general rate fund resources, collected mostly

from the properties in the urban core, for

providing services in the peri-urban areas.

is re-distribution of allocated services

within the LG areas can more eciently be

done at the local level.

Stabilisation

Stabilisation mostly relates to macro-

economic issues. Due to the macro nature

of the issues involved, national, this function

of public nance is primarily a central

government and central bank function.

REVENUE SOURCES FOR LOCAL

GOVERNMENT IN ZAMBIA

e major revenue sources for councils in

Zambia, apart from the intergovernmental

transfers, are Rates (property tax), Levies

(taxes on local, usually, business activities),

User Charges, Personal Levy (a Local tax on

personal income) and Licences (business

permits). e relative signicance of these

sources is somewhat dierent between the

dierent types of councils; City, Municipal

and District with rates (73%), User Charges

(70%) and Levies (60%) being by far the

leading source for each category respectively

as shown in Table 2-1.

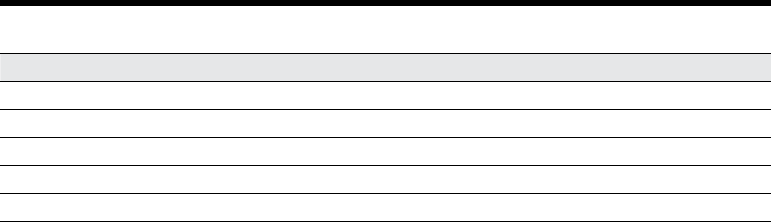

TABLE 2-1: Performance of Council Revenue Sources -2006

Type of

Council

# of

Respondent

Councils

Revenue Sources

Sub-Total

Average

Per

Council

Property

Rates

Levies

User

Charges

P. Levy Licenses

City 2

$4,481,707 $434,835 $1,018,633 $42,545 $97,069 $6,074,789 $3,037,395

73.8% 7.2% 16.8% 0.7% 1.6% 100.0%

Municipal 3

$128,723 $85,605 $656,718 $25,381 $41,345 $937,772 $312,591

13.7% 9.1% 70.0% 2.7% 4.4% 100.0%

District 4

$40,948 $379,140 $95,416 $51,840 $57,840 $625,184 $156,296

6.5% 60.6% 15.3% 8.3% 9.3% 100.0%

Total 9

$4,651,378 $899,580 $1,770,768 $119,766 $196,254 $7,637,745 $848,638

60.9% 11.8% 23.2% 1.6% 2.6% 100.0%

Compiled from data collected during (MoFNP-MLGH, 2008)

17

CHAPTER 3

THE CONCEPT OF FISCAL DECENTRALISATION

is chapter discusses the framework for

sharing the responsibilities and resources

discussed in Chapter 2, between dierent levels

of governments, scal federalism. It applies the

concepts within this framework to the process

transferring more of those responsibilities

those that can be so transferred to lower levels

of government, scal decentralisation.

WHAT IS FISCAL FEDERALISM AND

FISCAL DECENTRALISATION?

Fiscal Federalism

Fiscal federalism is the term used to

describe the “general normative framework for

the assignment of functions to dierent levels of

government and appropriate scal instruments

for carrying out these functions. It explores, both

in normative and positive terms, the roles of

the dierent levels of government and the ways

in which they relate to one another through

such instruments as intergovernmental grants”

(Sharma, 2003, p. 177) e concept applies

to most countries not just federations, since

most countries, other than City States such as

the Vatican or Singapore, have more than one

level of government.

A central theme of scal federalism and

decentralisation, therefore, is the existence of

a multi-level government.

Fiscal Decentralisation

Within this context, scal decentralisation

(FD) refers to the applications of the norms

of scal federalism to the process of devolving

service delivery responsibilities (expenditure

assignments) and the scal means to perform

those responsibilities (revenue assignments) to

lower level governments.

us scal federalism is ‘centralisation

– decentralisation’ neutral while scal

decentralisation applies these neutral norms in

the process of decentralisation. In ‘e Federal

Approach to Fiscal Decentralisation: Conceptual

Contours for Policy Makers’ (Sharma, 2003),

Sharma lists some concepts that contribute

to the creation of the right framework for

decentralisation. ese are discussed within

the Zambian context in the next section.

THE NEED FOR FISCAL

DECENTRALISATION IN ZAMBIA

e decentralization policy denes the need

for decentralization in Zambia as stemming

“from the need for the citizenry to exercise control

over its local aairs and foster meaningful

development which requires that some degree of

authority is decentralised to provincial, district

and sub-district levels as well as Councils, in

the background of centralisation of power,

authority, resources and functions, which has in

turn subjected institutions at provincial, district

and sub-district levels to absolute control by the

centre. In order to remove the absolute control by

the centre, it is necessary to transfer the authority,

functions and responsibilities, with matching

resources to lower levels”. (GRZ - Cabinet

Oce, 2002, p. 6)

is need “for the citizenry to exercise control

over its local aairs” has been a result of

deteriorating local service delivery over the

years arising primarily from reduced local

CHAPTER 3 THE CONCEPT OF FISCAL

DECENTRALISATION

18

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

revenue bases and unpredictable IGTs and the

resultant loss of human resource capacity as

the reduced revenue bases could not sustain

the required human resource recruitment,

development and retention.

e status of the available decentralisation

indicators, as outlined in Chapter 1, would

also seem to support the need for more

decentralisation..

Zambia’s Decentralisation Policy itemises

challenges within the current centralised

framework which the decentralisation process

is expected to address in respect of:

1. e Institutional Arrangements:

Challenges include; parallel administrative

structures at district level, absence of

sub-district level coordination structure

and lack of clear lines of authority and

reporting relationships between district,

provincial and national authorities;

2. Development Planning: Challenges include;

weak linkages between district planning and

national budgets and lack of local people

involvement in the planning process;

3. Human Resource Development and

Management: Challenges include; lack

of a comprehensive National Training

Policy, lack of capacity for councils to pay

skilled labour and lack of sta recruitment

guidelines for councils;

4. Infrastructure Development and

Management: Challenges include; Lack

of clear and comprehensive infrastructure

development and management policy, lack

of adequate human and nancial resources

and absence of a preventive maintenance

culture;

5. Financial Mobilisation, Utilisation

and Management: Challenges include;

Lack of a clear IGTs allocation formula,

unpredictable timing and value of IGTs,

out-dated nancial regulations;

6. Local Government Electoral System:

Challenges include lack of provisions

for; making the Mayor / Chair Person

accountable to the electorate, empowering

the Mayor / Chair Person to enforce

implementation of council resolutions and

empowering the Mayor / Chair Person to

enforce discipline ( currently no-executive

Mayor / Chair Person); and

7. Legal Framework: Challenges include;

lack of appropriate legislation to

support and guide decentralisation and

bureaucratic provisions requiring Central

Government approval of council by-laws

and budgets.

All these challenges have contributed to

poor levels of service provision at local levels

resulting in the need “for the citizenry to exercise

control over its local aairs” as demonstrated

by the “overwhelming” submission on local

government to the 2003 MCRC reported

by Simwinga (Simwinga, 2007, p. 16) and

more recently, discussions on the Barotse

Agreement (Kunda & Lewanika, 1964) as a

way for devolution

1

.

FISCAL DECENTRALISATION

CONCEPTS

Finance Follows Function

is means that when functions are assigned,

or there are changes in assigned functions,

to the dierent levels of government, those

assignments must be accompanied with

revenue raising authority to those levels of

government and, if necessary, equalisation

mechanisms to ensure adequate resources

are available for undertaking the assigned

responsibilities.

1 See also the following for discussions on the agreement:

http://

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barotseland

,

http://www.statehouse.

gov.zm/index.php/component/content/article/48-featured-

items/2636-bre-hands-over-barotse-report-to-president-banda

and

http://www.lusakatimes.com/2012/01/08/conspiracy-

theories-kk-abrogated-barotse-agreement/

19

CHAPTER 3

THE CONCEPT OF FISCAL DECENTRALISATION

From the discussions in 0, it is evident that

this concept has not been fully addressed in

the past. Present eorts in the development of

the IFA are aimed at addressing this shortfall.

Informed Public Opinion

In Zambia a key underlying rationale for

decentralisation is to encourage meaningful

local participation in matters of development

that aect them. For this to happen there must

be local availability and access to the right

information to enable the local community

to develop meaningful public opinion and to

decide local priorities.

An uninformed community is unlikely to

make informed choices.

Mechanisms for Articulating Local Priorities

While in Zambia it is assumed that

Councillors aord the community the

means for articulating their priorities, formal

systems for ensuring that this is so, are not

in place. Some council wards are extremely

large geographically and sub-ward structures,

such as the area development committees

(ADC) used in the DDPI, are not in place.

ese mechanisms for making local priorities

known must be in place to ensure that the

matters reaching the council chambers are in

line with the local priorities decided upon by

an informed community.

Other key community pillars, such as the

business community and civic society, must

also have means to articulate their needs.

eir needs might create the basis for Local

Economic Development (LED).

Adherence to Local Priorities

ere should be incentives for the councils

and the elected ocials to be responsive

to community priorities and accountable

to the community for delivering on those

priorities. Part of that incentive is the level of

community participation in monitoring the

delivery of services. e DDPI had a system

of public display of council monthly activities

and nancial data to enable the community

track council activities and validate them as

these were undertaken in the community.

When elected ocials and council ocers

are obliged to publicise information on

their activities and given an informed local

community, they are less likely to deviate from

the agreed local priorities as the informed local

community will note these variations and

apply appropriate injunction.

Incentives for Participation

For the community to participate there

must be incentives for that participation.

e ADC participation in the DDPI was

secured by the boreholes and feeder roads

developed from which the participants could

see the tangible output of their participation.

(Sharma, 2003, p. 39) states that “Writers on

institutional economics have long observed that

people’s willingness to participate varies according

to their perception of how much impact such

participation will have”.

Local Government Fiscal Responsibility

Zambia’s Medium Term Expenditure

Framework (MTEF) for Councils (MLGH,

2009) has the following three objectives;

Overall scal discipline, Allocative eciency

and Operational eciency. However the

“Eective incentive and sanctions frameworks

need to be in place to ensure accountability”

(MLGH, 2009, p. IX) cited as one of the

key features of an eective MTEF are not

yet in place. Fiscal indiscipline can cause

economic destabilisation but it is “argued that

destabilization eects of decentralization arose

mainly from inappropriate incentives than any

problem inherent in decentralization” (Sharma,

2003).

20

FISCAL DECENTRALIZATION IN ZAMBIA

Instruments to Support Decentralisation

e Decentralisation Policy is a statement of

political objectives. To achieve those objectives

other instruments relating to the creation of

an enabling environment require to be in

place. ese instruments are discussed as part

of the enabling environment in Chapter 4.

ISSUES FOR CONSIDERATION

Matching the assigned functions

(expenditure assignment) to the scal means to

perform those functions (revenue assignment)

and developing the means for addressing

scal imbalances that may arise between

these assignments is at the core of scal

decentralisation. Fiscal imbalances may relate

to vertical as well as horizontal imbalances.

Vertical Imbalance

Vertical Imbalance refers to scal imbalances

between the dierent levels of government.

is occurs when, at any level of government,

the expenditure assignments are greater than

the scal means to discharge these assignments

or, rarely, the available scal means are in

excess of the requirements for discharging the

expenditure assignments.

is imbalance can be caused by one or both

of the following conditions; inappropriate

allocation of revenue powers and spending

responsibilities, that is, scal asymmetry with

Vertical Fiscal Imbalance (VFI); or a desirable

revenue-expenditure asymmetry but with

a scal gap that needs to be closed, that is,

scal asymmetry without scal imbalance but

with a Vertical Fiscal Gap (VFG). Meaning

the right functions have been allocated on

the basis of which level of government can

best deliver which service and the right scal

means have been allocated on the basis of

which level of government can best collect

which revenues and still the rightly allocated

revenue sources are inadequate to undertake

the rightly allocated functions.

ere are two ways of addressing issues of

vertical imbalances; assignment of additional

(or less) local revenue raising powers and / or,

increase (or reduction) in intergovernmental

scal transfer to councils. Relating to which of

the two options is readily feasible for addressing

vertical imbalances (Bhal, 2000, p. 2) notes

“In developing and transition countries, there

are limited choices for the delegation of taxing

autonomy to local governments. e alternative

is to leave the bulk of revenue raising power at

the central level, and to provide a subsidy to

local government revenues to accommodate the

mismatch. e result is that transfers comprise

a major component of subnational government

revenues. As local governments grow into the

ability to use modern instruments of local

taxation, the importance of transfers diminishes.

In the U.S., for example, transfers nance less

than one-fourth

2

of all state and local government

expenditures and subnational governments have

access to a wide variety of consumption and

income taxes.”

Increased local revenue raising powers

While VFIs can normally be resolved

by increased local revenue raising powers,

however, issues of local scal capacity may