(ISC)

2

CYBERSECURITY

WORKFORCE STUDY

A critical need for cybersecurity

professionals persists amidst a year

of cultural and workplace evolution

2022

3

5

49

18

83

80

79

73

67

Executive Summary

Cybersecurity Workforce Gap & Estimate

Cybersecurity Team Culture

Career Pathways

Data Breaches, War and Modern Threats

Future of Cybersecurity Work

Conclusion

Appendix A – Workforce Gap and Estimate Methodologies

Appendix B – Study Participant Demographics

Table of Contents

2022 is a highly formative year for the cybersecurity profession. Shaped

and dened by geo-political and macroeconomic turbulence, the obstacles

of the modern cybersecurity landscape have galvanized passion and

persistence within its workforce - which continues to change and evolve

with the world around it. The global cybersecurity workforce is growing,

but so is the gap in professionals needed to carry out its critical mission.

We estimate the size of the global cybersecurity workforce at 4.7

million people – the highest we’ve ever recorded. According to our

research, however, the cybersecurity eld is still critically in need of

more professionals. To adequately protect cross-industrial enterprises

from increasingly complex modern threats, organizations are trying to

ll the worldwide gap of 3.4 million cybersecurity workers. To fully

contextualize the state of cybersecurity in 2022, we’ll analyze the eld

through multiple lenses.

At an enterprise level, the executive spotlight is pointed directly at

cybersecurity teams, who are expected to adapt and protect their

own organizations from mounting risks while complying with emerging

technology and regulatory requirements. Employees are adapting their

working style and routines to meet these modern challenges, but they

themselves are also evolving from cultural, emotional, and educational

perspectives, and these differences paint a nuanced picture of the values

and motivations that drive their careers.

As individuals, cybersecurity professionals are passionate about what they

do, and their organizations need to recognize this and bolster them with

the tools they need to succeed and continue charting a path forward for the

entire profession. It is clear in our study that corporate culture can be very

impactful on an employee’s experience and happiness on the job, which in

turn affects the efcacy of their work.

Executive Summary

3(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

The future of cybersecurity is dened by professionals evolving and

persisting through the volatility of today’s threat landscape. Traditional

habits are being broken and diverse perspectives are entering the eld,

as the next generation uses new pathways to jump-start their careers.

In this report, the fth annual (ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, we

surveyed 11,779 international practitioners and decision-makers to gain

their unique perspectives and experiences about working in the modern

cybersecurity profession. This report highlights hiring and recruiting trends,

corporate culture and job satisfaction, career pathways, certications,

professional development, how the workforce is adapting to current events

and what the future of cybersecurity work looks like.

4(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Before we can analyze the nuances and trends fueling change within the

modern cybersecurity profession, it is paramount for us to understand the

holistic nature of the eld itself – how it is growing and scaling to meet the

needs of organizations worldwide. Calculating a global workforce estimate

and gap are crucial to framing the remainder of this report.

To understand the scope of cybersecurity professionals worldwide, (ISC)

2

introduced the cybersecurity workforce estimate in 2019. This proprietary

methodology integrates a wide array of primary and secondary data

sources to extrapolate the number of workers responsible for securing their

organizations (see Appendix A for details).

(ISC)

2

estimates the global cybersecurity workforce in 2022 at 4.7 million, an

11.1% increase over last year, representing 464,000 more jobs. We saw gains

across all regions, with Asia-Pacic (APAC) registering the greatest growth

(15.6%) and North America the least (6.2%) (see gures 1-A and 1-B).

+6.2% +12.2% +12.5%

NORTH

AMERICA

1,344,538

LATAM

1,230,365

EMEA

1,222,154

+15.6%

APAC

859,027

4,656,084

2022 Global Cybersecurity Workforce Estimate

+11.1% YoY

Cybersecurity Workforce Gap & Estimate

FIGURE 1-A

Our study estimates the cybersecurity workforce of 14

countries in 4 regions (see Appendix A for more details).

5(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

-16.5%

+23.2%

+18.3%

+17.7%

+40.4%

+4.4%

+5.5%

U.S.

1,205,812

CANADA

138,726

+12.2%

FRANCE

189,733

+29.2%

GERMANY

464,749

-.01%

AUSTRALIA

143,680

+6.7%

MEXICO

542,418

+5.2%

UK

339,145

+13%

IRELAND

17,687

BRAZIL

687,947

SPAIN

153,167

NETHERLANDS

57,672

+64.3%

JAPAN

388,402

SINGAPORE

77,425

SOUTH

KOREA

249,520

FIGURE 1-B

4,656,084

2022 Global Cybersecurity Workforce Estimate

+11.1% YoY

6(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

While the cybersecurity workforce is growing rapidly, demand is growing

even faster. (ISC)

2

’s cybersecurity workforce gap analysis revealed that

despite adding more than 464,000 workers

in the past year, the cybersecurity workforce

gap has grown more than twice as much as

the workforce with a 26.2% year-over-year

increase, making it a profession in dire need

of more people (see gures 2-A and 2-B).

Despite adding more

than 464,000 workers

in the past year, the

cybersecurity workforce

gap has grown more

than twice as much as

the workforce.

2022 Global Cybersecurity Workforce Gap

3,432,476

+26.2% YoY

+8.5% -26.4% +59.3%

NORTH

AMERICA

436,080

LATAM

515,879

EMEA

317,050

APAC

2,163,468

+52.4%

FIGURE 2-A

Our study estimates the cybersecurity workforce gap for 16

countries in 4 regions (see Appendix A for more details).

7(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

2022 Global Cybersecurity Workforce Gap

3,432,476

+1.6%

-52.0%-61.7%

+57.5%

-29.0%

-19.0%

+37.9%

INDIA

563,364

+630.9%

CHINA

1,482,085

+20.9%

SPAIN

60,436

NETHERLANDS

26,265

SINGAPORE

6,071

SOUTH

KOREA

16,643

AUSTRALIA

39,496

+57.5%

JAPAN

55,809

IRELAND

8,481

GERMANY

104,197

+52.8%

FRANCE

60,859

+120.6%

UK

56,811

+73.4%

U.S.

410,695

CANADA

25,385

+9.0%

MEXICO

203,027

BRAZIL

312,852

+26.2% YoY

-21.8%

+21.5%

FIGURE 2-B

8(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

The workforce gap is not going unnoticed by cybersecurity workers – nearly

70% feel their organization does not have enough cybersecurity staff to

be effective. The shortage is particularly severe in aerospace, government,

education, insurance and transportation. A cybersecurity workforce gap

jeopardizes the most foundational functions of the profession like risk

assessment, oversight and critical systems patching. More than half of

employees at organizations with workforce shortages feel that staff decits

put their organization at a “moderate” or “extreme” risk of cyberattack.

And that risk increases substantially when organizations have a signicant

stafng shortage (see gure 3).

In your opinion, to what degree does this shortage of cybersecurity staff

put your organization at risk of experiencing a cybersecurity attack?

Organizations with

signicant staff shortage

Organizations with

slight staff shortage

20%

4%

Extreme risk

54%

41%

Moderate risk

15%

36%

Slight risk

7%

16%

Low risk

3%

1%

No risk

Base: 4,967 global cybersecurity professionals whose teams have staff shortages

FIGURE 3

9(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

In many areas, our study found that the workforce gap is being felt by

employees more than ever. Compared with last year, far more cybersecurity

professionals indicated that their organization had experienced issues

like lacking proper time for assessment and oversight of processes, slow

patching of critical systems and inadequate time and resources for training

as a consequence of stafng shortages (see gure 4).

Which of the following have you experienced that you feel would

have been mitigated if you had enough cybersecurity staff?

2021 2022

31%

29%

29%

23%

32%

23%

48%

43%

39%

38%

35%

32%

Not enough time for

proper risk assessment

and management

Oversights in process

and procedure

Slow to patch

critical systems

Not enough time to

adequately train each

cybersecurity team member

Miscongured

systems

Not enough resources to

adequately train our staff

Base: 4,967 global cybersecurity professionals whose teams have staff shortages

FIGURE 4

10(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

ADDRESSING THE WORKFORCE GAP

Why does this workforce gap exist? How can organizations best

mitigate it? Some factors are certainly out of an organization’s control

– demand for cybersecurity employees is bound to increase as the

threat landscape continues to grow in complexity and supply can’t

always keep up. Indeed, the inability to nd qualied talent was cited

most frequently as a challenge by organizations with cybersecurity

staff shortages (see gure 5). Yet while this may be the most common

challenge, it is not necessarily the most impactful.

To better understand what challenges are linked to the biggest

stafng shortages, we examined what percentage of employees at

organizations with those issues had signicant stafng shortages. This

analysis suggests that the most negatively impactful issues are ones

that organizations can indeed control: not prioritizing cybersecurity,

not sufciently training staff, and not offering opportunities for

growth or promotion. Being unable to nd qualied talent was

actually the least impactful problem based on this analysis.

11(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

You indicated that your organization has a shortage of cybersecurity staff.

What do you think are the biggest causes for this shortage?

Base: 4,967 global cybersecurity professionals whose teams have staff shortages

43%

My organization can’t nd enough qualied talent

33%

My organization is struggling to keep up with turnover/attrition

28%

My organization doesn’t have the budget

31%

My organization doesn’t pay a competitive wage

16%

My organization doesn’t have plans in place for backll roles

23%

My organization doesn’t put enough resources into training non-security IT staff

to become security staff

22%

Leadership misaligns staff resources (i.e., we have too much staff in some areas

and not enough in others)

24%

My organization can’t offer opportunities for growth/promotion for security staff

16%

My organization doesn’t sufciently train staff

19%

My organization doesn’t prioritize security

FIGURE 5

12(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

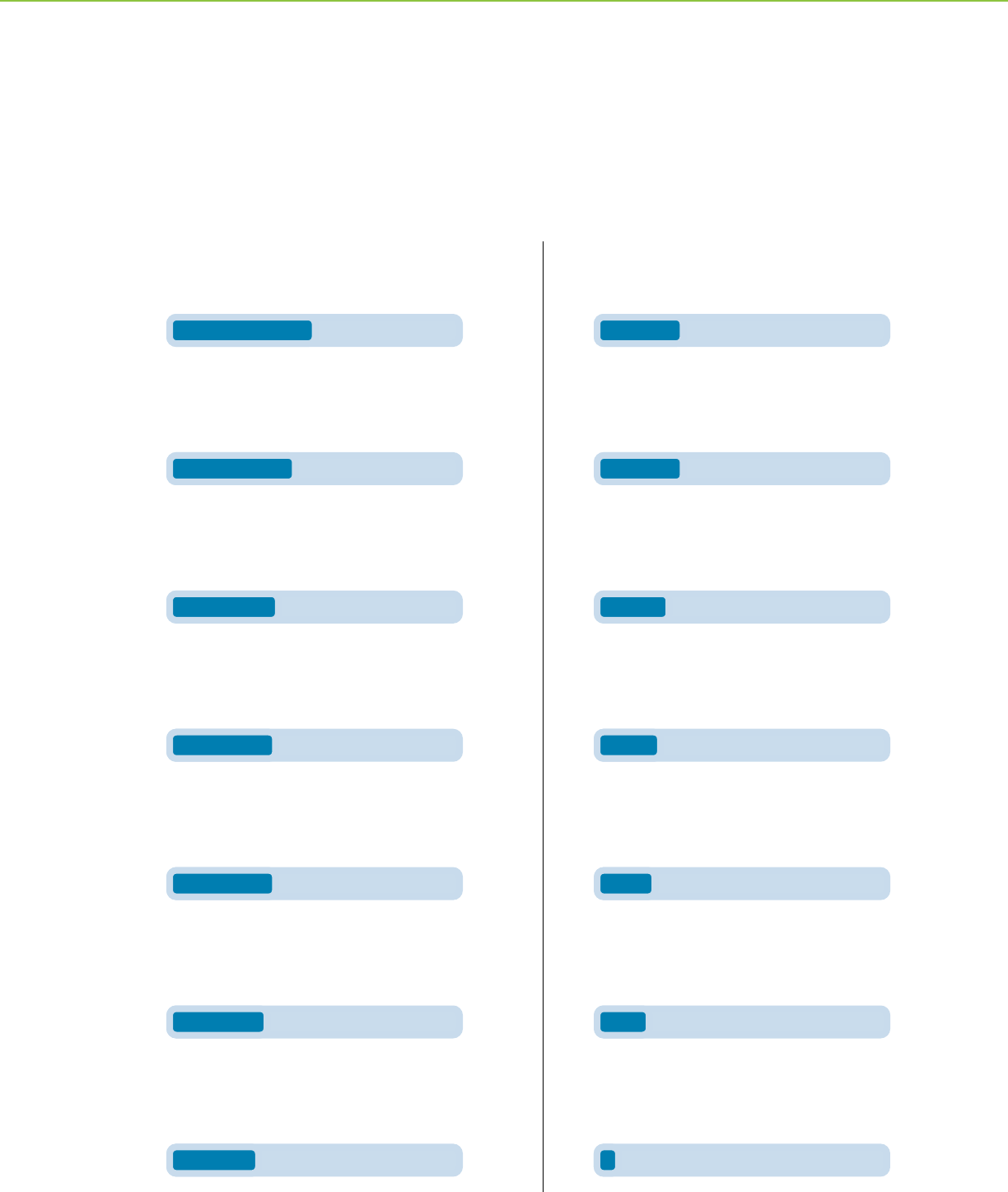

When we take a look at what is actually being done to address worker

shortages, we can see that organizations are indeed putting in the effort

to mitigate staff shortages (see gure 6). However, what they are doing

is not always what is most effective. Although almost all initiatives had a

positive impact on stafng, we found that organizations with initiatives to

train internal talent – rotating job assignments, mentorship programs and

encouraging employees outside of cybersecurity to join the eld – were

least likely to have shortages (see gure 7). These initiatives are particularly

impactful for larger companies – only 49% of companies with 1,000 or

more employees who had implemented all three of these internal training

initiatives had stafng shortages compared with 77% of those who had

implemented none.

These were not, however, the most commonly adopted initiatives. In fact,

many of the most effective initiatives had the lowest implementation levels.

The initiative with by far the lowest impact is outsourcing. Respondents at

organizations who were outsourcing cybersecurity were actually slightly

more likely to see a shortage in staff.

Automation is becoming more prevalent in cybersecurity as well – 57%

have adopted it today and an additional 26% plan to adopt it in the

future – and while it isn’t likely to take the place of cybersecurity workers at

any time in the foreseeable future, automating processes that are consistent

and repeatable frees up workers to focus on higher-level tasks. This may

reduce stafng shortage issues without requiring additional staff.

13(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Which of the following is your organization doing or planning to do to help

prevent or mitigate cybersecurity staff shortages at your organization?

Provide more exible working conditions

(e.g., Work From Home / Work From

Anywhere)

Invest in training

Recruiting, hiring, and onboarding

of new staff

Invest in certications

Invest in diversity, equity, and

inclusion initiatives (e.g., attract more

women and minorities to enter the

cybersecurity profession)

Use technology to automate

aspects of the security job

Hire for attitude and aptitude,

and train for technical skills

Use of outsourcing / services

(broadly dened)

Mentorship programs

Hire from outside the geographic regions

we typically have hired from because of

WFH (Work From Home) trends

Encourage employees at your organization

outside IT and security to consider a career

in cybersecurity

Address pay and promotion gaps,

if they exist

Implement rotational job assignments

(e.g., different roles within cybersecurity)

De-emphasis on technical degrees

and certications for new hires

64%

64%

62%

58%

57%

57%

50%

48%

45%

42%

41%

39%

33%

30%

Base: 11,525 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

71% of companies with

10,000+ employees are

doing these 3 things

26% of all respondents'

organizations are

planning to do this in

the future

FIGURE 6

14(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Which of the following is your organization doing or planning to do to help

prevent or mitigate cybersecurity staff shortages at your organization?

Base: 11,525 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

56%

Implement rotational job assignments (e.g., different

roles within cybersecurity)

33%

60%

39%

Address pay and promotion gaps, if they exist

61%

41%

Encourage employees at your organization outside IT

and security to consider a career in cybersecurity

63%

45%

Mentorship programs

30%

63%

De-emphasis on technical degrees and certications for new hires

65%

Use technology to automate aspects of the security job

57%

66%

64%

Invest in training

66%

42%

Hire from outside the geographic regions we typically have

hired from because of WFH trends

67%

62%

Recruiting, hiring, and onboarding of new staff

67%

58%

Invest in certications

67%

57%

Invest in diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives (e.g., attract

more women and minorities to enter the cybersecurity profession)

68%

64%

Provide more exible working conditions (e.g., Work From

Home/Work From Anywhere)

70%

48%

Use of outsourcing/services (broadly dened)

FIGURE 7

% WITH STAFFING

SHORTAGES

IMPLEMENTATION LEVEL

63%

50%

Hire for attitude and aptitude, and train for technical skills

15(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

When it comes to hiring, cybersecurity

managers can’t work alone. The

study nds that cybersecurity hiring

managers who had a strong working

relationship with their HR department

were far less likely to have signicant

stafng shortages at their organizations

(see gure 8). However, only 52% of

respondents said that hiring managers

have a strong working relationship with

HR, and 40% of hiring managers said

that the HR department at their

organization does not add value

to the recruiting process.

Cybersecurity hiring

managers who had

a strong working

relationship with their HR

department were far less

likely to have signicant

stafng shortages at their

organizations.

Which of the following best describes how you feel about the number of

cybersecurity employees your organization currently employs to prevent

and troubleshoot security issues at your organization?

Organizations where HR and cybersecurity

hiring managers collaborate very poorly

Organizations where HR and cybersecurity

hiring managers collaborate very well

49%

18%

My organization has a signicant shortage of cybersecurity

staff to prevent and troubleshoot security issues

37%

37%

My organization has a slight shortage of cybersecurity

staff to prevent and troubleshoot security issues

13%

38%

My organization has the right amount of cybersecurity

staff to prevent and troubleshoot security issues

1%

6%

My organization has a surplus of cybersecurity staff

to prevent and troubleshoot security issues

Base: 7,529 global cybersecurity professionals on in-house cybersecurity teams

FIGURE 8

16(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

THE CYBERSECURITY WORKFORCE GAP

Cybersecurity workers are in greater demand than they’ve ever been before

and supply can’t keep up. The global workforce gap increased by over 25%

this year and nearly 70% of organizations say they have a worker shortage.

Combatting stafng shortages is no easy task but ndings from our research

yield some key places where organizations can focus:

• Understand what your gap is. Senior-level practitioners in our study

were more likely than managers or executives to say their organization

had a stafng shortage. This suggests that those making decisions

may not always have a full appreciation of what front-line cybersecurity

professionals are experiencing. Decision-makers should make sure they

are actively listening to employees to understand if and where there are

stafng shortages.

• Emphasize internal training. Our study found that the most impactful

organizational initiatives in reducing worker shortages were those that

took advantage of internal talent with programs like rotational job

assignments, mentorship and encouraging non-IT employees at the

organization to learn about cybersecurity. This was particularly true for

larger organizations that may have more internal talent; it’s just a matter

of nding and honing it. The challenges that were most associated

with high stafng shortages were a lack of emphasis organization-wide

on cybersecurity, insufcient staff training and a lack of pathways for

growth.

• Work with HR, not against them when hiring for cybersecurity. Hiring

is a challenging process. While cybersecurity hiring managers likely

know best what kinds of candidates to look for, HR managers are more

likely to have the expertise on nding and attracting those candidates.

Therefore, it's crucial for cybersecurity organizations to build effective

working relationships with HR. Those who don’t were more than 2.5x

as likely to have signicant stafng shortages compared with those who

have built a strong relationship with HR.

WHAT IT MEANS FOR ORGANIZATIONS

17(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Company culture heavily denes employee experience. It shapes the social

environment that employees operate in. It impacts how they communicate

and collaborate with colleagues within their own team and across the

organization. And it can inuence how satised and supported they feel by

their employer at large, ultimately inuencing answers to the question of

“should I stay, or should I go?”

Staff shortages are a common challenge in the post-pandemic cybersecurity

environment. Many cybersecurity employees are being given increased

exibility and the freedom to choose where and how they work. People

are seeking out work cultures that t their lifestyles the best, and this has

led to increased turnover. 21% of respondents from North America have

switched organizations in the last 12 months; this is up from 13% in the

previous year.

For modern cybersecurity professionals, the denition of “corporate

culture” is changing as pre-pandemic norms are being shattered and

geographical lines are being blurred. In this critical area of our research, we

analyzed employee experience within cybersecurity, and particularly how

workplace trends and cultural nuances impact motivations, social values

and employee satisfaction. Although overall satisfaction with cybersecurity

work continues to be high, organizations may not be doing all they can to

maximize employee experience. For example, cultural divides between

junior and senior employees are widening, especially when it comes to the

perceptions of diversity, equity and inclusion.

Cybersecurity Team Culture

18(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

UNDERSTANDING CYBERSECURITY EMPLOYEE EXPERIENCE

Amidst a year of great change, we examined the cultural landscape

of modern cybersecurity professionals and found:

FOR MANY, JOB SATISFACTION REMAINS HIGH.

Respondent satisfaction was lower, however, with their specic

teams (68%), departments (62%), and overall organization (60%).

Unhappiness tended to come from workplace culture and issues,

rather than from cybersecurity work itself. Many who left their

jobs over the past two years cited higher pay and more growth

opportunities. But, concerningly, the next three reasons for leaving a

job are all related to workplace conditions: negative culture, burnout

and poor work/life balance (see gure 9). Overall, only 50% of those

polled saw a high likelihood they would remain at their current

organization for the next ve years.

Roughly 75% of those surveyed report being

“somewhat satised” or “very satised” with

their job and passionate about their work.

19(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

GROWTH

OPPORTUNITIES

NEGATIVE

CULTURE

You indicated that you left a job within the past two years,

what were the biggest reasons behind you making this move?

Base: 5,102 global cybersecurity professionals who have worked in their current role for 2 or fewer years

I left for emotional health reasons

I found a higher paying position somewhere else

I found a job with a better title/promotion

Lack of opportunities for advancement/career growth

I thought the work culture was negative/unhealthy

I felt burnt out

Bad work/life balance

My previous team lacked resources/budget

I changed industries/career focus

My previous team was too short-staffed

Moving locations (e.g., family move, spouse has a new work arrangement)

Lack of representation/support from a DEI perspective

Health issues

Need to care for a family member

Lack of childcare options

10%

31%

31%

30%

25%

21%

19%

14%

13%

13%

10%

6%

5%

5%

4%

FIGURE 9

20(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Employee Experience Rating

Respondents fall into three overall categories

based on their employee experience levels:

• EX scores are based on aggregated responses

from a series of employee experience questions

• Scores were indexed on a 100-point scale

for ease of analysis

HIGH EX

62 and

above

3,822

(32.6%)

42 - 61

4,175

(35.6%)

41 and

below

3,716

(31.7%)

SCORE N

MEDIUM EX

LOW EX

Employees with high level

of happiness at their work

Employees with a medium level

of happiness at their work

Employees with a low level of

happiness at their work

RATING EMPLOYEE EXPERIENCE

To better understand what affects the satisfaction and overall

experience of cybersecurity workers, we developed a rating system

that examines a variety of key factors, including engagement in work,

feeling worn out at the job, sense of being fairly evaluated, and

more. The Employee Experience (EX) rating system uses a scale from

100 (excellent) to 0 (terrible). For ease of evaluation, we grouped

respondents into three categories based on their scores – “High EX,”

“Medium EX” and “Low EX.” In this study, we will mainly evaluate the

extremes, that is, high versus low. We’ll use the EX rating throughout

this report to quantify results and provide a valuable data foundation

for our recommendations.

21(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Dening Employee Experience Rating

HIGH EX

MEDIUM EX

LOW EX

1.9%

0.7%

1.3%

1.2%

1.5%

1.8%

2.0%2.0%

2.1%

3.7%

2.8%

3.4%

3.7%3.7%

3.8%

4.0%

4.2%

3.9%

5.7%

4.6%

4.0%

4.4%

4.1%

3.3%3.3%

2.8%

2.6%

2.9%

1.9%

2.0%

1.8%

1.5%

1.9%

1.3%

0.7%

0.2%

0.3%

MOST RESPONDENTS LIKE CYBERSECURITY WORK, BUT UNHAPPINESS

WITH ORGANIZATIONS FUELS STAFFING SHORTAGES

The analysis of responses on corporate culture, through the lens of EX

ratings, provides evidence on what drives poor employee experience and

satisfaction. We found:

• Low scores were generally driven by organizational issues, not with

the cybersecurity work itself. High EX employees expressed greater

passion for cybersecurity work, as compared to their Low EX colleagues.

The differences between the groups became far greater when it came to

satisfaction with their teams, organizations and departments (see gure

10). In fact, 60% of Low EX workers agreed that they like cybersecurity

work but are not satised with their team/organization; this is compared

with just 16% of their High EX counterparts (see gure 12).

• Low EX is very harmful to organizations. The data suggests that

poor EX is a major contributor to stafng shortages. Compared to

their higher-scoring peers, Low EX employees indicate they are far less

motivated and productive at work and are much less likely to remain at

their organizations for long (see gure 11).

22(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

High EX Low EX

Please rate your feelings for each following item on a scale

from very low to very high.

(Percentage showing High/Very High responses)

Base: 11,086-11,779 global cybersecurity professionals

85%

68%

Passion for cybersecurity

work in general

Level of productivity

in my day-to-day

work (compared with

previous roles)

84%

57%

Satisfaction

with my team

Likeliness to stay at

my organization for

the next 2 years

82%

47%

Satisfaction with

my department

80%

44%

Motivation in my day-

to-day work (compared

with previous roles)

81%

44%

Overall satisfaction

with my organization

48%

81%

67%

40%

Likeliness to stay at

my organization for

the next 5 years

76%

54%

FIGURE 11 FIGURE 10

23(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

TOP FACTORS INFLUENCING

EMPLOYEE EXPERIENCE

Our survey results strongly suggest that EX and

satisfaction are closely tied to organizational

culture. But what are the most impactful factors

driving both high and low scores? To identify and

understand these, we rst looked at the most

common issues faced by respondents, as well as

the initiatives their organizations have put in place

to respond to these challenges. We then examined

the average EX rating of respondents who selected

each issue to see what resulted in the lowest and

highest ratings. We found:

• Not inviting and valuing worker input

signicantly contributes to poor EX.

Respondents were asked what issues negatively

impacted their job satisfaction. The most

common answer was having “too many emails/

tasks.” This is unsurprising, considering the

prevalence of stafng shortages. However,

employees being overworked, whether that’s

related to inadequate stafng or not, did not

negatively affect EX scores nearly as much as

a variety of cultural and organizational issues.

The most signicant factor of poor EX was the failure of organizations

to listen to or value employee input (see gure 13). Cybersecurity

professionals are passionate about their work, so while overwork is not

a positive thing, it is not as negative as feeling like their expertise and

knowledge are not being valued or asked for. The data shows that this

impact is felt particularly with older workers who may feel like their

experience has earned them the right to have a voice in the industry and

their organization. When these employees are not listened to, they do

not feel valued.

FIGURE 12

How much do you

agree or disagree

with the following

statements about your

security team’s culture

in general?

(Percentage showing

Agree/Completely Agree

responses)

High EX Low EX

60%

16%

Base: 11,525 global cybersecurity

professionals on cybersecurity teams

I like security work but

I’m not satised with

my team/organization

24(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

44.6

39.2

35.8

40.1

43.1

41.1

40.4

44.5

44.3

42.2

42.4

43.2

Which of the following are issues in your current role

that negatively impact your job satisfaction?

Lack of support from executives/managers

24%

23%

Pay is too low

22%

I get stressed out from the weight of responsibility I feel

as a security professional

19%

Poor security policies/standards at my company create extra

work for me

I feel like my job exists only to prevent breaches and I will

be blamed if one occurs

13%

22%

The organization is not realistic in the way they measure

success of security

10%

Securing a remote workforce has added more stress to my role

12%

Poor relationship with team members or managers

13%

My employer does not value or listen to my input

10%

There is no exibility or remote work option

16%

I am expected to work long hours

FIGURE 13

FREQUENCY

15%

Negative culture

AVERAGE EX

RATING

46.5

30%

Too many emails/tasks

Base: 11,525 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

25

(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

• Organizations that make employees feel heard have

happier personnel. On the ip side, the most common initiatives

that organizations have implemented to improve employee EX are

centered around work exibility, including remote work. However,

such programs, while now considered essential accommodations by

many workers, are not the most impactful. Instead, efforts to value

the input of all employees produced the highest average EX rating

(see gure 14). This is unfortunately not common, as only 28% report

their organizations actively listen to and value the input of all staff.

The next most benecial initiative, proactively soliciting feedback

on employees’ needs, is similarly not widespread with only 35%

reporting their organizations doing so.

According to respondents, the addition of extra vacation days

and recognizing birthdays and other special events were the least

impactful initiatives. Additionally, the institution of robust parental

leave policies was also near the bottom in terms of average EX,

though it was far more impactful for cybersecurity workers in their

30s, especially women.

26(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Which of the following has your organization done

in an effort to create a positive work culture?

56.0

32%

Team building/bonding exercises/activities (e.g., ofce happy

hour, company outings/trips)

57.6

28%

Proactively solicits feedback on employees’ needs

57.3

16%

Management and staff have created realistic KPIs

59.8

The organization values and listens to the input of all staff

28%

55.5

35%

Diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) training/initiatives

54.0

18%

Instituted robust parental leave policies

53.8

20%

Added extra vacation days

56.8

23%

Implemented technology to make security professionals’ jobs easier

54.8

35%

Implemented mental health support programs/resources

53.3

29%

Recognizes special events (e.g., holidays, birthdays etc.)

FIGURE 14

ORGANIZATION IMPLEMENTATION LEVEL

36%

Promoted cybersecurity awareness to the whole organization

56.4

AVERAGE EX

RATING

55.9

Encourages exible work hours (i.e., not strictly

working from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.)

42%

55.2

49%

Implemented exible work arrangements (e.g., employees

can work remote or at home)

Base: 11,525 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

27

(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Which of the following has your organization done in an effort to create a positive

work culture?

Promoted cybersecurity awareness

to the whole organization

36%

Implemented mental health support

programs/resources

35%

Diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI)

training/initiatives

35%

Proactively solicits feedback

on employees’ needs

28%

The organization values and listens

to the input of all staff

28%

Implemented technology to make

security professionals’ jobs easier

23%

Added extra vacation days

20%

Instituted robust parental leave policies

18%

Management and staff have created

realistic KPIs

16%

They have not done anything

to promote positive work culture

5%

Recognizes special events

(e.g., holidays, birthdays etc.)

29%

Implemented exible work

arrangements (e.g., employees can

work remote or at home)

49%

Encourages exible work hours

(i.e., not strictly working from 9

a.m. to 5 p.m.)

42%

Team building/bonding exercises/

activities (e.g., ofce happy hour,

company outings/trips)

32%

FIGURE 15

Base: 11,525 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

28

(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

WILDLY POPULAR, REMOTE WORK DOUBLES TO 55% ADOPTION

As previously noted, the most common initiative

organizations have implemented to create a

positive work culture is changing where and when

employees work (see gure 15). In the wake of

COVID-19, exible work arrangements have

become the norm. Prior to the pandemic, only

23% of cybersecurity professionals worked

remotely or had the exibility to choose where

they worked. Today, this number has surged to

55% (see gure 16).

Remote work has a substantial impact on employee

experience. The average EX ratings of respondents

working fully remote (54.4) and exible work (53.4) are higher than those

required to be full time in the ofce (48.0). Some 59% said they always

prefer to work remotely. Over half would consider switching jobs if they

were no longer allowed to work remotely.

Suspicion around remote work is still widespread, especially among

organizational leaders. 62% of non-manager cybersecurity professionals

say they are more productive when working from home; this is compared

to only 35% of managers who said remote staff are not as productive as

onsite staff.

Over half of

respondents would

consider switching

jobs if they were no

longer allowed to

work remotely.

29(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Base: 11,525 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

Prior to the

COVID-19 pandemic

8%

15%

19%

57%

Today

21%

34%

27%

17%

Two years from today

20%

35%

18%

16%

COMBATTING BURNOUT AT WORK STARTS AT HOME

The ability to avoid burnout was another key factor in EX ratings.

The move to remote work has allowed people to proactively combat

feelings of burnout that would otherwise weigh down their day-to-

day experiences. The traditional workday is now broken up with non-

work activities in between tasks, such as physical exercise and pursuing

hobbies and other passions after work hours. The average EX rating for

respondents using these tactics was higher than it was for those who tried

to avoid burnout by changing work environments, seeking mentorship,

passing responsibilities to others or changing jobs. Figure 17 shows the

relative effectiveness of each activity based on the average EX score of

respondents pursuing it. Remote workers engaged in the most effective

activities, i.e., physical exercise and taking breaks, much more than in-

ofce workers (see gure 18).

Which of the following best describes how you were working prior to the

COVID-19 pandemic? Which best describes how you are working today?

How do you think you’ll be working two years from today?

Designated fully

remote worker

Required to work in-ofce a

certain number of days per week

Flexible work (i.e., exibility to

choose where I work and when)

Required to work

in-ofce full time

FIGURE 16

30(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

What have you personally done to help combat/avoid burnout?

FIGURE 17

ACTIONS

AVERAGE EX

RATING

Base: 11,525 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

45%

Pursued hobbies and other passions

53.2

40%

Used PTO/leave

52.2

15%

Changed companies

49.3

13%

Changed positions

47.7

36%

Set boundaries around/reduced work hours

51.8

12%

Sought mentorship

46.8

14%

Volunteered/got involved with the community

49.1

Passed off responsibilities to others

19%

48.1

Ask my manager for support

18%

47.5

Took breaks during the workday

47%

53.3

53%

Physical exercise

53.7

31(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

What have you personally done to help combat/avoid burnout?

In-ofce full-time workers Fully remote workers

CYBERSECURITY IS BEGINNING TO SEE A GENERATIONAL DIVIDE

Attention and attitudes toward organizational culture in the cybersecurity

industry have changed considerably over the last ve years. Today, many

cybersecurity workers – especially younger ones – consider issues like

diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), emotional health and having a louder

voice to be a greater priority (see gure 19).

Many of these younger individuals have concerns about a perceived

cultural divide between junior and senior employees. They feel that

longer-tenured colleagues, their employer and the cybersecurity

profession have created a “gatekeeping” culture that limits opportunity

and advancement. (In the survey, “gatekeeping” was dened as an

articial or unnecessary barrier such as requirements for education,

Took breaks during

the workday

58%

37%

Physical

exercise

56%

48%

Pursued hobbies

and other passions

49%

41%

Set boundaries around/

reduced work hours

41%

28%

Base: 11,779 global cybersecurity professionals

FIGURE 18

32(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

certications or specic skills). Nearly 25% of respondents below the age

of 30 considered gatekeeping and generational tensions as their top-ve

challenges for the next two years; this is compared to just 6% of workers

who are 60 or older (see gure 20).

Findings suggest a connection between these hot-button issues and EX

scores. In our survey, workers who voiced the strongest concerns in these

areas had the lowest average ratings; the least concerned workers had the

highest ratings (see gure 21).

To what extent do you agree with each of the following

statements related to how the security industry’s culture

has changed in the past ve years?

(Percentage showing Somewhat/Completely Agree responses)

60 or older 39-4950-59 30-38 Under 30

66%

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) are more important today than 5 years ago

57%

63%

61%

64%

Employees have more of a voice than they did 5 years ago

43%

48%

54%

58%

50%

Base: 11,525 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

Emotional health is a greater priority compared with 5 years ago

54%

58%

60% 60%

67%

FIGURE 19

33(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

How much do you agree or disagree with the following

statements about your security team’s culture in general?

(Percentage showing Agree/Completely Agree responses)

60 or older 39-4950-59 30-38 Under 30

There is a gatekeeping culture within the security profession

31%

32%

40%

45%

44%

There is a cultural divide between experienced and junior employees on our security team

25%

26%

34%

42%

43%

I like security work but I’m not satised with my team/organization

24%

27%

35%

39%

40%

Base: 10,683-11,347 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

There is a gatekeeping culture within my team

20%

21%

30%

36% 36%

FIGURE 20

34(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

FIGURE 21

To what extent do you agree that there is a gatekeeping

culture within your team?

(Showing Average EX Rating)

Base: 10,752 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

Completely agree

40.0

Somewhat agree

45.8

Neutral

50.0

Somewhat disagree

54.2

Completely disagree

62.0

35(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

CYBERSECURITY TEAM CULTURE

Cybersecurity team culture is crucial to reducing employee turnover and

increasing productivity. Our study found that cybersecurity personnel

generally love cybersecurity work but that does not mean they are always

happy in their particular organization or team. Unhappy employees are less

productive and more likely to leave, costing organizations valuable time and

resources to replace them. Our study found that Low EX workers were more

than twice as likely to be employed at organizations with signicant stafng

shortages. This suggests a vicious cycle: organizations with poor EX lose

staff, and this creates stafng shortages which harms EX even further. On

top of retention issues, 68% of Low EX employees say that workplace

culture impacts their effectiveness in responding to cybersecurity

incidents.

The key ndings for organizations that are looking to prevent issues with

employee experience are as follows:

• Value your employee’s voice. Respondents not feeling as if their

voices are being heard resulted in the lowest EX rating on average.

Consequently, those at organizations that implemented initiatives to

listen to and value the expertise of all cybersecurity staff had the highest

EX rating of any organizational initiative. Therefore, it’s crucial that

cybersecurity leadership listens to and values the voice of all employees.

• EX initiatives pay off. While some initiatives to improve organizational

culture have a greater impact, it’s worth noting that all have a net

positive effect on EX. Organizations should not discount the importance

of these initiatives to improve the morale of cybersecurity teams.

WHAT IT MEANS FOR ORGANIZATIONS

36(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

• Flexible work options have become the norm. The pandemic changed

the way in which employees expect to work. 55% of respondents

currently have the exibility to choose where they work on a daily basis,

and 84% have the ability to work at home at least part time. Over half

of workers say they would consider switching jobs if they were no

longer allowed to work remotely. Organizations that are not offering

exible work arrangements are going to fall behind their competition

and lose workers.

• Prepare for a changing workforce. Younger workers note that they

are frequently feeling a cultural divide; this extends to the idea that

many organizations have a “gatekeeping” culture. Organizations need

to understand how the workforce at large is changing and begin to

adapt. Fostering collaborative relationships between junior and senior

employees can go a long way in creating a more productive and

harmonious transition to a new generation of cybersecurity workers.

68% of Low EX employees say

that workplace culture impacts

their effectiveness in responding

to cybersecurity incidents.

37(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

DIVERSITY, EQUITY AND INCLUSION

Across the world, the cybersecurity profession is rapidly changing

and experiencing profound demographic shifts in age, gender, race

and ethnicity. The divide between younger and older cybersecurity

professionals is the greatest within DEI. This gap is the result of both

generational changes in culture and in demographics themselves. For

example, in our study, women accounted for 30% of global cybersecurity

workers who are under the age of 30; additionally, they accounted for just

14% of those 60 or older. Dramatic shifts are happening even faster in race

and ethnicity demographics (see gures 22-A and 22-B). In this study, we

looked at racial and ethnic differences among cybersecurity professionals

in the U.S., Canada, the United Kingdom and Ireland. In each country, the

cybersecurity workforce has historically been dominated by white men,

who comprise nearly 70% of the 60 or older respondents but only 40%

of those under 30 (see gure 23). Cybersecurity professionals expect this

demographic shift to increase even further, with 55% saying the workforce

will be more diverse two years from today.

FIGURE 22-A

Age Group By Race

Base: 6,110 cybersecurity professionals in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Ireland

Note: The demographic distributions of gender, race and ethnicity should be considered a representation of the survey sample and not necessarily

reective of the cybersecurity industry as a whole.

60 or older

19% 81%

22% 78%

32% 68%

42% 58%

49% 51%

50-59

39-49

30-38

Under 30

Non-white White

38(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

FIGURE 22-BFIGURE 23

Age Group by Gender

Age Group By Race And Gender

Base: 11,155 global cybersecurity professionals

Note: The demographic distributions of gender, race and ethnicity should be considered a representation of the survey sample and not necessarily

reective of the cybersecurity industry as a whole.

Base: 4,266 cybersecurity professionals in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Ireland

Note: The demographic distributions of gender, race and ethnicity should be considered a representation of the survey sample and not necessarily

reective of the cybersecurity industry as a whole.

60 or older

60 or older

14%

69% 13% 15% 3%

3%

6%

12%

22%

19%

26%

30%

27%

10%

10%

10%

7%

84%

12%

68%

85%

13%

61%

85%

24%

48%

74%

30%

40%

69%

50-59

50-59

39-49

39-49

30-38

30-38

Under 30

Under 30

Women Men

White men Non-white menWhite women Non-white women

39(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

WHO’S THE BOSS? IT MAY BE CHANGING

Our survey found that higher positions are much less diverse than lower

ones, e.g., only 23% of C-level cybersecurity executives identied as being

non-white; this is compared with 47% of entry-level staff. It generally

follows that the non-White population in cybersecurity tends to be much

younger and less likely to be in executive positions.

In terms of gender, we’re seeing more women, especially younger ones,

holding managerial positions. In our study, women made up only 10%

of C-level executives who are 50 or older, but they account for 35% of

all executives in their 30s. Interestingly, women across the board remain

underrepresented in advanced, non-managerial positions, where they

make up only 17% of our respondent base.

Gender and race were dened in the following ways for this study:

Gender: Respondents self-identied their gender as being either

male, female or non-binary. Respondents who identied as non-binary

represented a sample that was too small to statistically analyze, so

results are not shown.

Race: Respondents were able to select any racial or ethnic group to

which they felt they belonged. For the purposes of analysis, we dened

“White” as any respondent who selected both “White/Caucasian”

and no other racial/ethnic group. “Non-White” respondents are

dened as those who selected a racial/ethnic group other than “White/

Caucasian.” “Non-White” respondents also include mixed-race

respondents who might have also selected “White/Caucasian.”

40(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

COUNTRIES

MOST

GENDER-

DIVERSE

LEAST

GENDER-

DIVERSE

INDUSTRIES

Retail/wholesale

Healthcare

Entertainment/media

Insurance

Engineering

Transportation

Non-security software/

hardware development

Financial services

Security software/

hardware development

Consulting

26%

17%

74%

83%

23%

15%

77%

85%

22%

15%

78%

85%

22%

14%

78%

86%

19%

13%

Nigeria

Mexico

Ireland

Brazil

India

34% 66%

34% 66%

33% 67%

31% 69%

30% 70%

81%

87%

Netherlands

United Kingdom

United States

Germany

Japan

16% 84%

16% 84%

13% 87%

13% 87%

10%

90%

Women Men

Base: 11,155 global cybersecurity professionals

Note: The demographic distributions of gender, race and ethnicity should be considered a representation of the survey sample and not necessarily

reective of the cybersecurity industry as a whole.

41

(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

YOUNGER WORKERS HIGHLY VALUE DEI

As demographics and cultural forces change, so do attitudes toward

DEI. Younger employees placed far greater value on DEI than their older

colleagues. For workers under 30, organizational diversity initiatives had

the second-highest impact on EX ratings; this is behind organizations

valuing and listening to their input. For those over 60, DEI had the lowest

impact on EX.

Younger employees also have different expectations. When asked to

rate their organization on a scale from 1 to 10 for their efforts in diversity

with age, disability, gender, sexual identity and race/ethnicity, younger

employees judged their organizations much lower than their senior

colleagues did in all ve categories (see gure 24). Age divides are more

dramatically intersected with gender and race/ethnicity. For example,

younger women and non-White employees were far more likely than any

demographic to agree with the following statements: “It’s important that

my security team is diverse” and “Diversity has contributed to my security

team’s success” (see gures 25 and 26). Additionally, many agreed with

this statement: “I don’t feel like I can be authentic and fully myself at

work.” It’s troubling that 30% of women and 18% of non-White employees

worldwide say they feel discriminated against at work.

30% of women and 18% of non-

white employees worldwide say they

feel discriminated against at work.

42(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

FIGURE 24

How would you rate your organization in terms of diversity in each of the

following categories?

(Respondents ranked their responses on a scale of 1-10 where 1 is “not at all

diverse” and 10 is “very diverse”)

Base: 11,525 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

60 or older 50-59 30-38 Under 3039-49

Race and ethnicity

7.57

7.29

7.11

7.20

7.18

Sexual identity

7.11

6.79

6.80

6.86

6.70

Gender

7.30

7.09

6.83

6.90

6.76

Ability level (including

neurodiverse and those

with a disability)

6.49

6.14

6.17

6.17

5.95

43(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

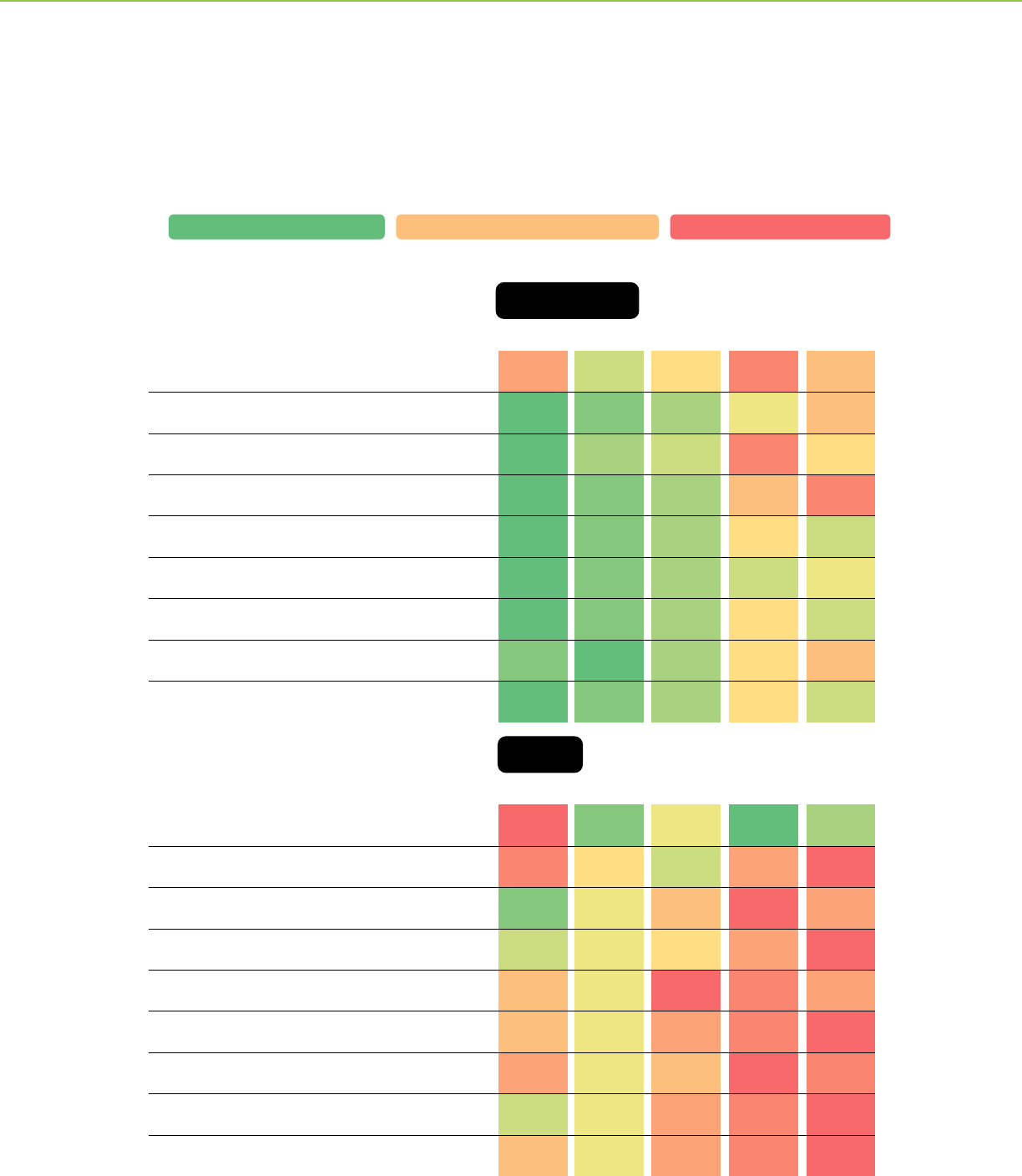

FIGURE 25

Who agreed most with these statements related to DEI?

Base: 4,360 cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Ireland

NON-WHITE

WHITE

Green — strongest agreement Yellow/orange — medium agreement Red — strongest disagreement

Promoting diversity is a part of my

organization’s culture

Promoting diversity is a part of my

organization’s culture

I feel discriminated against at my workplace

I feel discriminated against at my workplace

I don’t feel like I can be authentic and fully

myself at work

I don’t feel like I can be authentic and fully

myself at work

Diversity within the security team has

contributed to my security team’s success

Diversity within the security team has

contributed to my security team’s success

The employees at my company care more

about DEI than my organization does

The employees at my company care more

about DEI than my organization does

It’s important that my security team is diverse

It’s important that my security team is diverse

My organization’s DEI initiative has had a

signicant impact on my daily work life

My organization’s DEI initiative has had a

signicant impact on my daily work life

My company is not doing enough to address

DEI issues

My company is not doing enough to address

DEI issues

We are not given a sufcient amount of

training related to DEI

We are not given a sufcient amount of

training related to DEI

Under 30 39-4930-38 50-59 60 or older

Under 30 39-4930-38 50-59 60 or older

44(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

FIGURE 26

Who agreed most with these statements related to DEI?

Base: 11,525 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

Green — strongest agreement Yellow/orange — medium agreement Red — strongest disagreement

WOMEN

MEN

Under 30 39-4930-38 50-59 60 or older

Under 30 39-4930-38 50-59 60 or older

Promoting diversity is a part of my

organization’s culture

Promoting diversity is a part of my

organization’s culture

I feel discriminated against at my workplace

I feel discriminated against at my workplace

I don’t feel like I can be authentic and fully

myself at work

I don’t feel like I can be authentic and fully

myself at work

Diversity within the security team has

contributed to my security team’s success

Diversity within the security team has

contributed to my security team’s success

The employees at my company care more

about DEI than my organization does

The employees at my company care more

about DEI than my organization does

It’s important that my security team is diverse

It’s important that my security team is diverse

My organization’s DEI initiative has had a

signicant impact on my daily work life

My organization’s DEI initiative has had a

signicant impact on my daily work life

My company is not doing enough to address

DEI issues

My company is not doing enough to address

DEI issues

We are not given a sufcient amount of

training related to DEI

We are not given a sufcient amount of

training related to DEI

45(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

DEI has a big impact on workplace culture. For many,

especially young women and young people of color,

this impact is focused on the employee experience. Not

surprisingly, cybersecurity workers who say they feel on-the-

job discrimination and the inability to be themselves at work

report signicantly lower EX ratings (see gure 27).

FIGURE 27

To what extent do you agree

with the following statement:

“I don't feel like I can be

authentic and fully myself

at work.”

(Numbers showing Average

EX Rating of respondents)

Completely agree

Somewhat agree

Neutral

Somewhat disagree

Completely disagree

39.4

41.5

46.8

54.4

62.9

Base: 10,325 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

To what extent do you agree

with the following statement:

“I feel discriminated against

in my workplace.”

(Numbers showing Average

EX Rating of respondents)

Completely agree

Somewhat agree

Neutral

Somewhat disagree

Completely disagree

35.5

36.9

45.1

50.8

59.8

46(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

DEI

For both individual employees and organizations, DEI is an important issue.

Our study found that DEI programs play a signicant role in preventing

or aggravating workforce shortages. Just 19% of organizations that have

implemented DEI initiatives reported signicant shortages of cybersecurity

staff; this is compared to 34% of those who haven’t and don’t plan to do so.

Our research also discovered organizations that offered more DEI initiatives

had higher average EX ratings. This makes sense considering that nearly

two-thirds of respondents said an inclusive environment is essential for their

team’s success.

WHAT IT MEANS FOR ORGANIZATIONS

FIGURE 28

What types of programs/initiatives/tools does your company

use to promote DEI and accessibility?

DEI training for employees

Anonymous and clear pathways to report discrimination

DEI events

DEI employee groups or afnity groups

DEI council or committee

Job descriptions that refer to DEI programs/goals

Don’t know/does not apply

We do not have any DEI initiatives

HR team that supports employees who feel discriminated

against in the workplace

Skills-based hiring (evaluating talent objectively based

on skills and potential)

Accessible workplace design (Remote-work option,

technology for persons with disabilities, etc.)

38%

35%

34%

34%

30%

29%

27%

22%

17%

6%

40%

Base: 10,325 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

47

(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Base: 10,325 global cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams

United States

Ireland

Sweden

United Kingdom

Canada

Hong Kong

Japan

South Korea

France

China

1

2

3

4

5

1

2

3

4

5

COUNTRIES/ECONOMIES WITH

MOST DEI INITIATIVES:

COUNTRIES/ECONOMIES WITH

FEWEST DEI INITIATIVES

However, despite wide employee support, our study found that DEI-

related initiatives are not widespread. Only 40% of respondents said their

organizations offered employee DEI training (see gure 28). Countries

in North America and Europe (except France) tended to offer more DEI

initiatives; Asian countries offered the fewest.

Countries with fewer initiatives tended to have more racially and

ethnically homogenous populations. Given that DEI extends beyond

race and ethnicity to address gender, age, sexual identity and ability, the

discrepancies are noteworthy.

DEI is an opportunity available to executive leaders. Social politics and

ideologies aside, organizations should take a pragmatic look and consider

the real, increasingly clear connection between DEI initiatives and

cybersecurity stafng.

48(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

As corporate cybersecurity culture evolves to dene the employee

experience, career pathways are being carved out by the next generation.

New trends and perspectives are emerging, i.e., evolution is motivating

people and organizations to value education, certications and practical

skills differently than they have in the past.

We surveyed respondents from all walks

of life who are using their own education

(both institutional and personal) and

professional experience (both in and out

of IT) as starting blocks to break into the

industry. Here’s what we learned:

• For younger workers, more roads

lead to cybersecurity. Nearly half of

respondents under the age of 30 move

into cybersecurity from a career outside

of IT. Younger professionals are more likely to use their education in

cybersecurity or a related eld (23%) as a stepping stone to either enter

the profession or move from a totally different eld (13%) outside the IT

or cybersecurity landscape. Some are even recruited after their own self-

education within cybersecurity (12%). As respondents approach ages 50

to 54, we observed a peak in the number of employees who have used

a career in IT as their pathway into the eld (74%), demonstrating that

this very popular practice is no longer the primary source for recruiting

younger cybersecurity talent (see gure 29).

The primary driver for

earning certications in

the future is fueled by a

need to improve skills for

a specic position (64%).

Career Pathways

49(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Which of the following best describes your pathway into a job in cybersecurity?

Base: 11,347 global cybersecurity professionals

Started in IT then

moved to cybersecurity

Started in another eld then

moved to cybersecurity

Pursued education in cybersecurity or related

eld then got my rst job in cybersecurity

Other

Explored cybersecurity concepts on my own

and was recruited for a job in cybersecurity

65 or older

70% 20% 3%3%

3% 5%

4%

45-49

72% 13% 9% 6%

39-44

66% 14% 13% 6%

9%

35-38

59% 15% 16%

30-34

53% 17% 20% 10%

Under 30

50% 14% 23% 12%

60-64

73% 18%

2%

2%

1%

1%

1%

1%

1%

55-59

74% 15% 4%

4% 4%

3%3%

50-54

77% 13%

FIGURE 29

50(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

• Cybersecurity professionals are highly educated. Out of those

surveyed, 39% have attained a bachelor’s degree as their highest

form of education, 43% have earned a master’s degree, and 5%

have attained a doctorate (3%) or post-doctoral (2%) degree (see

gure 30).

As we look deeper into the different perspectives and demographics

present within our research, we can extract some interesting ndings.

For example, women in cybersecurity are more likely to hold master’s

degrees than men (49% compared with 42%). In addition, 55% of

non-White cybersecurity professionals hold a master’s, doctorate or

post-doctoral degree; this is compared to 44% of White respondents

(see gures 31-A and 31-B).

What is the highest level of education you have completed?

Base: 11,779 global cybersecurity professionals

Post-doctoral (or equivalent)

2%

Doctorate (or equivalent)

3%

Two-year associate's degree (or equivalent)

6%

High school diploma (or equivalent)

6%

Master’s degree (or equivalent)

43%

Bachelor’s degree (or equivalent)

39%

FIGURE 30

51(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

What is the highest level of education you have completed?

6,110 cybersecurity professionals on cybersecurity teams in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Ireland

Non-white professionals White professionals

3%

2%

Doctorate (or equivalent)

4%

8%

Two-year associate's degree (or equivalent)

4%

6%

High school diploma (or equivalent)

50%

41%

Master’s degree (or equivalent)

36%

41%

Bachelor’s degree (or equivalent)

Post-doctoral (or equivalent)

2%

1%

FIGURE 31-A

52(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

What is the highest level of education you have completed?

4%

7%

Two-year associate's degree (or equivalent)

49%

42%

Master’s degree (or equivalent)

36%

39%

Bachelor’s degree (or equivalent)

Women

2%

4%

Post-doctoral (or equivalent)

Men

Doctorate (or equivalent)

4%

3%

7%

High school diploma (or equivalent)

3%

Base: 11,155 global cybersecurity professionals

FIGURE 31-B

53(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

Which of the following best describes the focus of your education?

Bachelor’s degree

51% 19% 30%

Master’s degree

56% 15% 30%

Doctorate

47% 13% 40%

Post-doctoral

44% 11% 45%

Computer and information sciences Engineering/engineering technologies Other area of study

Base: 281-10,302 global cybersecurity professionals who hold these degrees

Most of the surveyed cybersecurity professionals focused their

education on computer and information sciences, with 51% of

bachelor’s degrees and 56% of master’s degrees having been

earned within this eld. Engineering was the next most common

background, with 19% of bachelor’s degrees and 15% of master’s

degrees coming from engineering. The remaining 30% are

comprised of a mix of business, communications, social sciences,

mathematics, economics, biological and biomedical sciences and

other degrees outside of IT (see gure 32).

FIGURE 32

54(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

• For new hires, experience and practical skills are growing in

importance. From 2021 to 2022, practical skills and experience

have grown into being more important qualications for those

considering employment in the cybersecurity profession. In

particular, more emphasis is being placed on relevant IT work

experience (29% to 35%), strong problem-solving abilities (38% to

44%) and relevant cybersecurity work experience (31% to 35%).

The ubiquitous importance of certications

was less prioritized this year (29% vs. 32%), as

were cybersecurity qualications or trainings

(17% vs. 23%), graduate degrees (10% vs. 13%)

and undergraduate degrees (10% vs. 14%) (see

gure 33).

Interestingly, when we look at how different

genders responded to this data, we can see

that women value cybersecurity degrees more

than men, and men place signicantly more

emphasis on practical skills like problem-solving

and communication. This is in line with the

fact that a greater percentage of women in

the cybersecurity eld hold degrees in higher

education (see gure 31-B).

From 2021 to 2022,

practical skills and

experience have

grown into being

more important

qualications for

those considering

employment in

the cybersecurity

profession.

55(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

What are the most important qualications for cybersecurity professionals

seeking employment?

(Showing top 6 increasing and decreasing trends)

Base: 11,779 global cybersecurity professionals

20222021

INCREASING TRENDS DECREASING TRENDS

Attending conferences

4%

7%

Internships/apprenticeships

4%

7%

Relevant IT work experience

35%

29%

Cybersecurity certications

29%

32%

Strong problem-solving abilities

44%

38%

Cybersecurity or related graduate

(i.e., Master’s or Doctorate) degree

10%

13%

Cybersecurity or related undergraduate

(i.e., two- or four-year college) degree

10%

14%

Cybersecurity qualications (e.g., trainings,

etc.) other than certications or a degree

17%

23%

Strong strategic thinking skills

27%

23%

Relevant cybersecurity work experience

35%

31%

Knowledge of basic cybersecurity

and cybersecurity concepts

33%

28%

Knowledge of advanced cybersecurity

and cybersecurity concepts

31%

25%

FIGURE 33

56(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

• Despite a high level of work, cybersecurity is a rewarding

profession that is growing in recognition. When all is said and

done, cybersecurity professionals feel passionate about their work.

While they often feel overworked (70%), an even higher number

stated that it is a rewarding profession (78%). 76% agree that

there is more appreciation for it than in the past, with another 74%

of respondents saying that they love their job. It’s important to

note that there are hardly any differences within these categories

when we compared respondents in their current positions with

those who were at the same organization for a year or less, vs.

those who were with a company for more than two years. This

suggests that cybersecurity professionals are passionate about

their work, regardless of age or experience (see gure 34).

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements about

the security profession?

(Showing Somewhat/Completely Agree responses)

Cybersecurity is a rewarding profession

Cybersecurity professionals are valued at my organization

It is easier now to get into cybersecurity

than when I entered the profession

Certications are easier to get today

than they used to be

78%

There is more appreciation for cybersecurity

professionals than there has been in the past

76%

Base: 11,779 global cybersecurity professionals

I love my cybersecurity job

74%

73%

Certications are more important earlier

on in a security career than later

60%

Our organization is increasing its cybersecurity

professional development, training, and

education over the next 12 months

55%

55%

37%

Cybersecurity employees are often overworked

70%

There are hardly any differences

amongst the top three categories

regardless of the respondent’s

years in their current position

or years at their organization.

43% of hiring

managers say this

compared to 29% of

non-hiring managers.

FIGURE 34

57(ISC)

2

Cybersecurity Workforce Study, 2022

• Twice as many people view internal promotion as their next

career milestone vs. changing jobs. Despite cybersecurity’s high

turnover in 2022, respondents indicated that they would generally

prefer internal promotion (30%) over getting a new job (15%); this

is compared to moving to a new eld within cybersecurity (12%),

becoming an independent contractor (6%) or starting a business

(6%) (see gure 35).

When we look deeper, those who seek promotion are also more

likely to be happier at their jobs. 36% of those with High EX want

to progress their career through internal promotion vs. just 24%

with Low EX. In addition, women (34%) are more likely to view

promotion as their next career step, compared to men (29%).

How do you see your cybersecurity career progressing in the next ve years?

Base: 11,779 global cybersecurity professionals

30%

Get promoted

6%

I want to start my own

security business

6%

Don’t know/ does not apply

?

15%

Move to a new job

3%

Move out of cybersecurity

12%

Move to a new eld within cybersecurity

3%

Other (please specify)

6%

I would like to work as an independent

security contractor for a different company

than the one I’m working at now

20%

I expect to be in the same role

in ve years

Signicantly more people with High EX