Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 1

National Fish and Wildlife Foundation

Chesapeake Bay Business Plan

August 2012 (Revised August 2018)

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 2

Purpose of a Business Plan

The purpose of a NFWF business plan is to provide a concise blueprint of the strategies and resources

required to achieve the desired conservation outcomes. The strategies discussed in this plan do not

represent solely the foundation’s view of the actions necessary to achieve the identified conservation

goals, but instead reflect the majority view of the many federal, state, academic, and organizational

experts that consulted during plan development. This plan is not meant to duplicate ongoing efforts but

rather to invest in areas where gaps might exist so as to support the efforts of the larger conservation

community.

Acknowledgements

NFWF gratefully acknowledges the time, knowledge, and support provided by individuals and

organizations that contributed significantly to this business plan through input, review, discussion, and

content expertise relative to the Chesapeake Bay watershed. In particular, thanks goes to the following

individuals who provided technical assistance with analysis, application, and interpretation of scientific

tools and data in support of NFWF’s business planning effort: Emily Trentacoste, U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency, for assistance in production, interpretation, and application of water quality data

and TMDL implementation progress from the Chesapeake Scenario Assessment Tool; Shawn Rummel

and colleagues, Trout Unlimited, for assistance in the application of Eastern brook trout conservation

portfolio analysis; Stephen Faulkner and colleagues, U.S. Geological Survey and CBP Brook Trout Action

Team, for expert advice on brook trout strategy development and monitoring needs; Stephanie Westby

and colleagues, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, for assistance identifying planned

oyster restoration activities; Tim Jones and Kirsten Luke, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service/Atlantic Coast

Joint Venture, for assistance with tailored analysis and application of the Black Duck Decision Support

tool; and Matt Ogburn, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, for development of river herring

prioritization models and identification of monitoring needs. In addition, NFWF wishes to thank key

stakeholders from the Chesapeake Bay Program for ongoing partnership and counsel in maximizing

NFWF’s contributions to partnership goals and outcomes.

About NFWF

Chartered by Congress in 1984, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) protects and restores

the nation’s fish, wildlife, plants and habitats. Working with federal, corporate and individual partners,

NFWF has funded more than 4,500 organizations and generated a conservation impact of more than

$4.8 billion. Learn more at www.nfwf.org.

Note on Business Plan Presented to NFWF’s Board of Directors

This version of the business plan does not include appendices due to board book space constraints.

Additional materials will accompany the public version of this plan.

Photo credit: All photographs provided by the Chesapeake Bay Program.

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 3

Background

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (“NFWF”) is updating its Chesapeake Bay Business Plan to

reflect the latest conditions in the watershed, particularly in light of recent funding trends, development

of new partnership-based Bay restoration and protection goals, and the availability of new data and

information to focus effort and measure conservation impact.

As one of the largest watershed restoration efforts in the world, the federal–state Chesapeake Bay

Program (“CBP”) partnership has been charged since 1983 with directing the coordinated actions of

federal and state agencies, local governments, non-profit organizations and academic institutions

working to protect and restore the Chesapeake Bay.

NFWF is a core partner of the CBP and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”), specifically

working to advance local on-the-ground watershed restoration actions, build local capacity for

restoration, and accelerate innovation in watershed management through conservation grant-making,

technical assistance, information exchange, and technology transfer.

NFWF’s role in the Chesapeake began in 1999 when it was competitively selected to administer the

EPA’s newly-authorized Small Watershed Grants program. Since then, NFWF has secured additional

competitively-awarded EPA funding to expand its work advancing watershed restoration efforts,

including funding from the Innovative Nutrient and Sediment Reduction Grants program and the legacy

Targeted Watershed Grants program.

NFWF’s Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund (“Stewardship Fund”) has further grown over time to

incorporate a range of additional federal, corporate, and private foundation partners and now invests

$10-15 million annually in on-the-ground restoration projects, technical assistance activities, and

directed partnerships to advance major Chesapeake initiatives. All told, NFWF has invested in excess of

$150 million across more than 1,000 individual projects, leveraging more than $200 million in additional

local funding for a total conservation impact of nearly $350 million. These investments have collectively

reduced annual nutrient pollution by nearly 25 million pounds, restored more than 1,800 miles of

riparian habitat and 6,700 acres of wetland, and engaged more than 2 million watershed residents

through outreach, training and volunteer opportunities.

NFWF formalized its long-term commitment to advancing Chesapeake restoration with the 2012

Chesapeake Bay Business Plan. The Business Plan outlines a comprehensive strategy to guide NFWF’s

conservation investments in the region through 2025 and establishes clear and achievable conservation

goals to enhance the resilience of the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem, increase populations of priority

species, reduce harmful pollutants from entering streams, rivers and the Bay, and reduce the costs of

the recovery effort. With a $100 million budget, NFWF has already invested $50 million in support of the

Chesapeake Bay Business Plan in its first seven years.

Shortly after the adoption of NFWF’s Chesapeake Bay Business Plan, the federal government and

watershed jurisdictions renewed their commitments to Chesapeake watershed restoration and

protection through the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, which outlines shared goals and

outcomes across a broad range of conservation and community engagement efforts. This update, in

part, is aimed at maximizing alignment of NFWF’s Chesapeake Bay investments with the new

partnership-based Watershed Agreement.

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 4

Conservation Need

Recognized as a “national treasure” for its historical, cultural,

economic, and ecological significance, the Chesapeake is the largest

estuary in North America and one of the most productive in the

world. Its watershed stretches across more than 64,000 square miles

in the Mid-Atlantic United States covering areas of six states and the

entirety of the District of Columbia. Its watershed spans from

Norfolk, Virginia to Cooperstown, New York and from the sandy

coastal plains of Delmarva Peninsula in the east to the headwaters of

the Potomac River in West Virginia’s Appalachian Mountains.

Compared to its vast watershed, the Chesapeake estuary itself is

relatively small with a surface area of just 4,500 square miles. The

relatively narrow mouth of the Bay further influences a unique set of

estuarine processes that limits the rate at which water and

constituent pollutants are flushed out of the Bay and into the Atlantic Ocean.

1

The result is that the Bay

and its tributary rivers and streams are particularly vulnerable to land-based activities throughout its

contributing watershed.

The Chesapeake and its watershed has undergone intense alteration and development since John Smith

and other early European settlers arrived in Jamestown in the early 17

th

century. To generate arable

land capable of sustaining growing colonial populations, early settlers extensively cleared native forests

and drained marshes and wetland systems.

This loss of forest and wetland cover, combined with the damming of streams and channelization of

rivers for navigation and commerce accelerated throughout the 19

th

and 20

th

centuries, leading to the

loss of nearly two-thirds of the watershed’s precolonial forest and wetland habitats, degradation of two-

thirds of stream habitats and declines in many culturally and economically important species. These

land use changes also increased the flow of nutrients and sediments to the Chesapeake and its tributary

rivers and streams, directly contributing to major declines in Chesapeake water quality and estuarine

habitat conditions, namely dissolved oxygen, chlorophyll, water clarity and underwater Bay grasses.

Compounding these watershed-scale impacts, overharvesting of the Chesapeake’s once bountiful finfish

and shellfish resources have further decimated the estuarine ecosystem.

Water Quality

While declines in Chesapeake water quality and associated habitat conditions trace their roots to

centuries of land use change, the more recent intensification in both agricultural production and urban

and suburban development across the watershed have accelerated nutrient and sediment loading and

associated estuarine habitat declines.

Agriculture. Agriculture, especially livestock and dairy production, remains a major economic and

cultural facet the region and represents the largest single source of nutrient and sediment pollution to

the Chesapeake. Unfortunately, the chemical fertilizers that revolutionized the global agricultural sector

1

Du, J. & Shen, J. (2016). Water residence time in Chesapeake Bay for 1980-2012. Journal of Marine Systems, 164,

101-111.

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 5

in the 20th century are frequently applied at rates that exceed what plants can readily absorb. Dramatic

shifts in animal agriculture in the past century have also led to intensification of livestock and dairy

production, resulting in manure “hotspots” where nutrient supplies far exceed needs for local crop

production. As a result, fertilizers are too often applied at rates and times inconsistent with local crop

needs, leading excess fertilizers to run off into surface waters or leach from nutrient-saturated soils into

groundwater supplies. Furthermore, some livestock producers still allow their animals free access to

streams for watering based on cultural norms established by earlier generations. The result is erosion of

stream banks, destruction of riparian vegetation, and direct deposit of animal manure into surface

waters.

Development. The Chesapeake watershed is home to nearly 18 million people, including the densely-

populated I-95 corridor from Richmond, Virginia to Baltimore, Maryland. Development of the

Chesapeake watershed represents a unique and growing challenge. While agriculture still contributes

the largest share of nutrient and sediment pollution to the Chesapeake, urban and suburban areas are

the only growing sources of these pollutants.

Urban development and associated impervious surfaces have dramatically altered local hydrology across

the Chesapeake watershed. Roofs, roads, sidewalks, and other built surfaces prevent rain from filtering

through the soil and impact both the timing and the quality of runoff entering local streams. Collectively,

these impervious surfaces speed the delivery of rainfall to surface waters, increasing the volume and

velocity of runoff entering stream channels, eroding streambanks and degrading the stream channel

itself. Furthermore, impervious surfaces prevent rainwater from filtering through the soil, which further

limits the natural pollution filtering service of the soil profile and causes stormwater runoff to transport

excess pollution directly to local streams.

Species and Habitat

Eastern Brook Trout. Eastern brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) are the only native trout species in the

Chesapeake Bay watershed. They are prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the

state fish of New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Residents of the Chesapeake’s headwater streams,

Eastern brook trout require cool, clean water. Wild brook trout populations in the Bay watershed have

significantly declined over the past two centuries. Factors affecting brook trout include land use and

warmer temperatures that degrade high quality stream habitats, and increased competition from other

species and the loss of genetic integrity. In the Chesapeake watershed, most brook trout are confined to

headwater streams, where disturbance is minimal and forest cover is still prevalent.

American Black Duck. The American black duck (Anas rubripes) was at one time the most abundant

dabbling duck in eastern North America and comprised the largest portion of waterfowl harvests in the

Mid-Atlantic region. Between the 1950s and 1980s, North American black duck populations declined by

more than 50 percent, due largely to conversion of wetlands habitats to other land uses and the loss of

associated food supplies. Situated along the Atlantic Flyway, the Chesapeake Bay watershed is especially

critical as wintering habitat for the species, supporting the largest share of the species’ wintering

populations. Restoring and protecting wetland habitat in the Chesapeake is viewed as critical to the

long-term sustainability of the species and the achievement of continental population goals.

River Herring. Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) and blueback herring (A. aestivalis), collectively known as

river herring, were once abundant in the Chesapeake’s tidal tributaries. As diadromous fish, river herring

travel from the ocean to high quality tidal rivers and streams to spawn. Each spring, massive herring

runs helped to sustain native communities and early colonial settlers. However, throughout the 18th

and 19th centuries, river herring suffered a precipitous decline due to overharvesting and the

construction of dams, which restrict access to high quality spawning habitats. Land use changes resulting

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 6

in the loss of riparian habitat and increases in impervious services have further degraded the quality of

spawning streams. While fishing is now restricted in both Virginia and Maryland, barriers to fish passage

and degraded stream health continue to negatively impact river herring throughout the watersheds.

Eastern Oysters. With its name roughly translated as “great shellfish bay” in the language of the

Chesapeake watershed’s native Algonquin tribes, it is no surprise that the Chesapeake Bay has long been

renowned for its shellfish resources. The Chesapeake is well known for its blue crabs (Callinectes

sapidus), but Eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica) have played a particularly prominent role in the

culture, history, and economy of the region. Native oyster beds were once so extensive that they

regularly posed navigational hazards for the Chesapeake’s early pilots. They were ecologically significant

as well, with some estimates that the native oyster population in the Chesapeake was capable of

filtering the entire volume of the estuary roughly every eight days. Oyster reefs also serve as key habitat

for a variety of aquatic species and a driver of the estuary’s broader food chains. As an economic

resource, oysters have helped to build many fishing communities along the Chesapeake with harvests

reaching nearly 20 million bushels per year at their peak. However, overharvesting, disease, and declines

in estuarine and bottom habitats have ravaged native oyster populations. Eastern oysters now represent

less than two percent of their peak historical populations.

Current Conservation Context

Since 1999, the Stewardship Fund has evolved into a robust set of competitive grant programs, directed

partnership investments, and program-wide support functions to help advance the goals of the CBP

partnership, funded primarily by the EPA and supported by a range of other public and private funders.

During that time, and after nearly three decades of significant, voluntary restoration efforts failed to

achieve necessary improvements in Bay water quality, the EPA took the landmark step in December

2010 of establishing an enforceable regulatory framework for limiting nutrient and sediment pollution

to the Bay. The Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) establishes science-based limits on

nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment pollution to the Bay necessary to achieve specific nearshore, open

water and benthic habitat conditions for dozens of the fish and shellfish species. Watershed jurisdictions

developed and are now executing Watershed Implementation Plans to ensure all pollution controls

needed to fully restore the Bay and its tidal rivers are in place by 2025.

The CBP partnership also recently renewed its shared commitment to a broader array of watershed

restoration and protection actions through the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement. Signed by

the EPA Administrator and chief executives from each of the watershed jurisdictions and building on

decades of earlier restoration agreements, the Agreement outlines ten goals and 31 associated

outcomes spanning habitat restoration and fisheries management, water improvement, land

conservation, and citizen stewardship efforts. Detailed management strategies and work plans are now

being executed by the CBP’s Goal Implementation Teams to achieve Agreement goals and outcomes.

NFWF’s Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund, guided by this updated Business Plan, will complement

regional, multiparty watershed restoration, habitat improvement, and citizen engagement efforts led by

EPA and the CBP by focusing on actions and investments that hold promise to simultaneously maximize

partner outcomes for water quality, species and habitat, and communities throughout the watershed.

NFWF will continue to make investments in building the technical capacity of partner organizations to

scale up their local restoration and protection efforts, including the support of innovative technologies

and program delivery approaches that have demonstrated success in accelerating restoration progress

ever since NFWF’s original 2012 Chesapeake Bay Business Plan.

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 7

Conservation Outcomes

NFWF is committed to the vision of “an environmentally and economically sustainable Chesapeake Bay

watershed” set forth in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement. To that end, NFWF’s Chesapeake

Bay Business Plan has been developed to provide measurable contributions to goals and outcomes of

the Chesapeake Bay Program and the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement associated with:

1. Water quality improvement through nutrient and sediment reduction to serve as the foundation

for healthy fisheries, habitats and communities across the Chesapeake Bay region;

2. Restoring and protecting key Chesapeake bay species and their habitats; and

3. Fostering an engaged and diverse citizen and stakeholder presence that will build upon and

sustain progress.

This Business Plan update revises selected goals and outcomes for the program established in 2012.

Progress to date has allowed NFWF to increase selected goals and outcomes as a reflection of

accelerated progress to date, new data and information have allowed NFWF to better refine and focus

its investments, and revised partner goals adopted in the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement

warrant better reflection in NFWF’s own strategic program vision. In sum, these changes represent

NFWF’s commitment to adaptive management in order to maximize the impact and relevance of its

programs to existing regional partners. See Appendix A for additional information on goal revisions.

Specifically, NFWF will focus investments on achieving the following outcomes:

Water quality

NFWF will improve water quality in the Chesapeake Bay by reducing: 1) nitrogen pollution by 10 million

pounds annually, or 13% of the nitrogen load reduction required by the Chesapeake Bay TMDL; 2)

phosphorus pollution by 1 million pounds annually, or roughly 25% of the phosphorus load reduction

required by the Chesapeake Bay TMDL; and 3) sediment pollution by 200 million pounds annually, or

6% of the sediment load reduction required by the Chesapeake Bay TMDL. Activities contributing to

these outcomes by 2025 include:

Improving water quality in agricultural areas by implementing best management practices to

reduce polluted runoff from 1 million acres, or 11% of the area in priority subwatersheds.

Improving water quality in urban and suburban areas by implementing green stormwater

infrastructure practices to treat, capture, and/or store 150 million gallons of stormwater runoff.

Continually increase the capacity of forest buffers to provide water quality and habitat benefits

throughout the watershed by restoring 1,000 miles of riparian forest buffer and associated

riparian habitat, or 10% of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement goal.

Improving the health and function of 1,500 stream miles, equal to 10 percent of stream miles in

priority subwatersheds and consistent with the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement goal, in

order to continually improve stream health and function throughout the watershed.

Eastern brook trout

NFWF will support recovery of Eastern brook trout in the Chesapeake Bay

watershed by maintaining and increasing Eastern brook trout populations

in 6 stronghold patches, as measured by number of effective breeders,

consistent with the goals of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement.

Activities contributing to this outcome by 2025 include:

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 8

Increasing habitat integrity in six stronghold patches through protection and restoration of

riparian areas, stream restoration, nonpoint source pollution controls and land use protections.

NFWF will also support efforts to increase the size of occupied patches and average patch size

through culvert replacement, dam removal, and fish passage improvement activities and where

proposed projects can identify and address potential impacts from the introduction of nonnative

brook trout species when conducting connectivity actions.

American black duck

NFWF will support the recovery of American black duck by increasing

wetland habitat and available food to support 5,000 wintering black

ducks, or 5% of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement goal for

wintering black duck populations. Activities contributing to this outcome by

2025 include:

Creating, reestablishing, or enhancing the function of 7,000 acres of tidal and non-tidal wetlands

to increase black duck carrying capacity through improved food resources.

Increasing available food resources by 680 million kilocalories.

River herring

NFWF will support recovery of river herring populations in the Chesapeake

Bay watershed by restoring access and use of 200 additional miles of high

quality migratory habitat, or roughly 10% of the Chesapeake Bay Program

goal. Activities contributing to this outcome by 2025 include:

Implementing 10 high priority, cost-effective connectivity enhancement projects through culvert

replacement, fish passage improvements, and dam removal.

Eastern oyster

NFWF will support recovery of Eastern oyster by supporting partner efforts

to restore oyster populations in five Chesapeake Bay tributaries, or 50% of

the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement goal, in order to continually

increase estuarine habitat and water quality benefits from restored oyster

populations. Activities contributing to this outcome by 2025 include:

Restoring 250 acres of native oyster reefs in targeted tributaries through spat production and

reef construction.

Capacity and planning

In order to achieve this plan’s conservation outcomes, NFWF will support efforts to motivate 40,000

individuals in the watershed to adopt behaviors that benefit water quality, species, and habitats.

Examples include adoption of on-farm conservation and residential stormwater management practices.

NFWF will achieve this outcome by building the capacity of citizens, organizations, institutions, local

governments, and partner networks to implement conservation actions through outreach, technical

assistance, and volunteer campaigns. Activities contributing to this outcome by 2025 include:

Enlisting 25,000 individuals in local volunteer events to restore local natural resources and

providing hands-on education and skill-building for individual action.

Developing or improving 1,000 conservation, watershed, or habitat management plans that

provide guidance to landowners, organizations, or local governments on how to manage

properties and communities for improved conservation outcomes.

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 9

Geographic Focus

A core element of NFWF’s Chesapeake Bay Business Plan is that strategic investment in priority places

will allow NFWF to maximize shared outcomes for water quality, species, and habitat. Accordingly,

NFWF will geographically focus its Stewardship Fund investments first in priority subwatersheds where

NFWF and its partners have identified significant opportunity to reduce nutrient and sediment loading,

specifically from agricultural and urban sources. NFWF will also use existing data and decision support

tools developed by partner organizations to further target those areas where species-specific

interventions can help to improve habitat and restore populations of Eastern brook trout, Eastern

oysters, American black duck, and river herring within priority subwatersheds.

NFWF anticipates that a significant share of Stewardship Fund funding will be deployed in priority

subwatersheds based on the unique opportunities to maximize multiple goals and outcomes.

However, NFWF will continue to support water quality improvement activities across the Chesapeake

Bay watershed in addition to habitat and species-specific activities in strategic locations that may be

outside of priority subwatersheds.

Table 1 presents the various data and decision support tools used to establish NFWF’s geographic focus

areas for the Stewardship Fund. Expert consultation, as well as additional supplementary datasets were

instrumental in refining these areas. Detailed maps of geographic priority areas can be found in

Appendix A and at NFWF’s online Chesapeake Bay Business Plan Mapping Portal.

Focal Area

Data Source(s)

Data Description

Water Quality

Chesapeake

Assessment Scenario

Tool (CAST)

Priority subwatersheds were identified as those representing the 5% of

land area delivering the highest per acre nutrient yield to the tidal Bay

and per acre sediment yield to local streams from agricultural and urban

sources as of 2016. (See Figure 1).

Eastern brook

trout

Eastern Brook Trout

(EBT) Conservation

Portfolio and Range-

wide Assessment

NFWF will focus on efforts to increase populations in stronghold

patches, population units with the highest resiliency to disturbances,

likelihood of demographic persistence, and representation of genetic,

life history, and geographic diversity. (See Figure 2).

American black

duck

Black Duck Decision

Support Tool (DST)

NFWF will focus wetland restoration, creation, and enhancement efforts

in subwatersheds with a projected deficit of available food resources,

while generally supporting efforts to stem future marsh loss across the

species non-breeding range. (See Figure 3).

River herring

Smithsonian

Environmental

Research Center

NFWF has identified the top 30 culverts in priority rivers based on

herring habitat use modeling and barrier prioritization approaches that

account for barrier severity, elevation and upstream development, and

current connectivity with existing habitat. (See Figures 4, 5, and 6).

Eastern oysters

Chesapeake Bay

Program Fisheries

Goal Implementation

Team

NFWF will supplement state and Federal oyster reef restoration efforts

in tributaries identified by the Chesapeake Bay Program and support

complementary activities in adjacent subwatersheds that minimize

disturbance and increase survivorship for these reefs. (See Figures 7 and

8).

Table 1. Data sources and descriptions for focal areas of NFWF’s Chesapeake Bay Business Plan

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 10

Implementation Plan

The key strategies for this Business Plan include, first and foremost, efforts to reduce nutrient and

sediment pollution to the Chesapeake Bay and its tributary rivers and streams, particularly from

agricultural and urban sources. NFWF will then prioritize pollution reduction and water quality

improvement activities that directly result in either habitat improvements for priority species or

reduction of key threats to populations of priority species. The Business Plan will also include a more

limited set of high-priority habitat restoration and management actions to benefit priority species that

may require additional interventions. These strategies will be supported by investments to enhance the

capacity of watershed partners to deliver effective conservation planning, programs, and partnerships at

increasing geographic scales, and to effectively engage those watershed stakeholders critical to

achieving the plan’s conservation goals. A logic model mapping these strategies, associated interim

outcomes, and their contribution to Business Plan goals is provided in Figure 9.

Strategy 1: Managing Agricultural and Urban Runoff

1.1 Managing Upland Agricultural Runoff Through Farm-Scale Conservation Systems and Solutions

Agricultural operations in the Chesapeake Bay region are often complex systems balancing goals for crop

and livestock production, management of agricultural inputs and animal waste, and financial

performance and stability. NFWF will support efforts to reduce water quality impacts while

simultaneously maintaining or increasing profits, reducing costs, and enhancing financial performance of

the region’s farms through the implementation of suites of best management practices that reduce

pollution at the farm scale. Selected examples include:

Soil health management systems that combine improved tillage and pasture management,

cover crops, crop and livestock rotations, and other practices to increase soil fertility while

improving the capacity of crops and soils to reduce runoff and increase nutrient uptake.

Precision nutrient management systems that fine-tune the rate, source, method, and timing of

organic and synthetic nutrient applications to maintain or increase crop yields while minimizing

nutrient input costs and associated losses to surface and groundwater.

Certification, labeling, and other sustainable sourcing initiatives that provide price premiums

and/or new markets for agricultural products produced in a manner that improves and protects

water quality and/or habitats.

“Whole-farm” conservation systems that package a variety of public and private financial

assistance programs to reduce pollution from crop and pasture lands, animal production areas,

and high-value natural resource areas like wetlands and riparian areas and significantly improve

the environmental performance of the farm.

1.2 Managing Upland Urban Runoff through Green Stormwater Infrastructure Improvements

NFWF will assist local governments, nonprofit organizations, and community associations to improve

urban and suburban stormwater management by implementing green stormwater infrastructure

practices that capture, store, filter, and treat stormwater runoff closer to its sources. Green stormwater

infrastructure practices (also known as environmental site design and low impact development

approaches) reduce the impacts of roofs, parking lots, and other impervious surfaces on local waterways

by replicating natural hydrologic processes and attenuating the volume, energy, and pollutant

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 11

concentrations of stormwater runoff. Example practices include rain gardens, bioswales and other

bioretention approaches, conservation landscaping, and urban tree canopy among others. In limited

cases, NFWF may also support urban floodplain and stream restoration for water quality improvement

where existing or planned green stormwater infrastructure initiatives effectively control stormwater

runoff from upland sources (see Strategy 2.1).

1.3 Accelerating Innovation in Watershed Management

In addition to support for innovative approaches to regional scale partnership development (see

Strategy 4.1), NFWF will support the in-field application of new technologies and management

approaches with the potential to reduce costs, increase nutrient removal efficiencies, and more

effectively control emerging pollutant sources. For instance, advancements in manure processing and

management, market-based solutions to manure management, innovative stormwater practices and

design approaches, and improvements in the cost-effectiveness of proven water quality improvement

approaches all show promise.

Strategy 2: Riparian and Freshwater Habitat Restoration, Conservation, and Management

2.1 Restoring Riparian and Freshwater Habitats through Forested Buffers, Floodplain and Wetland

Reconnection, and Stream Restoration and Habitat Improvements

In combination with actions to manage runoff, NFWF will help to restore degraded riparian habitats to

improve water quality, enhance aquatic habitat, and increase fish populations across the Chesapeake

Bay region through a variety of actions and interventions including but not limited to the following:

Implementation of riparian forested buffers slows and intercepts polluted surface and

groundwater runoff while providing long-term benefits for priority fish species through shading

of the stream channel and as a source of leaf litter, an important food source for aquatic

macroinvertebrates, a critical link in the food cycle of healthy streams including for the diets of

priority fish species.

Reconnection of stream channels with historic floodplains and adjacent wetlands will further

promote nutrient removal and attenuation of erosive stormflows and build more resilient

riparian systems.

Stream restoration

2

in both urban and rural landscapes will help to control streambank erosion,

increase in-stream nutrient processing, and provide food, cover, and habitat for priority species.

2.2 Increasing Habitat Integrity for Eastern Brook Trout

In combination with pollution reduction, riparian habitat restoration, and conservation actions, NFWF

will increase connectivity within and between occupied Eastern brook trout patches through dam

removal, repair and replacement of culverts and road crossings, and other fish passage improvements.

NFWF will support similar connectivity improvements to increase the amount of occupied habitat and

number of Eastern brook trout where local partners can demonstrate: (1) sufficient existing habitat

integrity to support brook trout populations; and (2) the absence of current or planned populations of

nonnative trout species in otherwise extirpated patches adjacent to occupied habitats.

2.3 Improving Riparian Management through Livestock Exclusion

In agricultural landscapes, uncontrolled access of livestock to the stream channel can cause streambank

erosion, stream channel degradation, and discharge of animal manures directly to surface waters. NFWF

will support efforts to implement livestock exclusion fencing, along with complementary practices like

2

Includes natural channel design, legacy sediment removal, and regenerative stormwater conveyance approaches.

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 12

stream crossing and off-stream watering, in order to balance livestock management needs with riparian

and stream health.

2.4 Conserving High-Quality Riparian Corridors

High quality stream habitats and riparian corridors are some of the most important ecosystems in the

Chesapeake Bay watershed, especially its headwater regions. NFWF will support long-term protection

and preservation of these ecosystems by strategically leveraging federal, state, and local land

conservation programs through assistance with transaction and due diligence costs, bonus payments for

high-value riparian easements, and incorporation of riparian protection into existing agricultural land

preservation programs.

Strategy 3: Estuarine and Tidal Habitat Restoration, Conservation, and Management

3.1 Restoring Large-Scale Oyster Reefs

NFWF will assist existing efforts to restore and protect large-scale oyster reefs strategically identified by

the Maryland, Virginia and the CPB by leveraging funding from federal and state agencies to support

oyster larvae and spat production, development of sustainable reef substrate supplies, and reef

construction efforts in established oyster reef restoration tributaries.

3.2 Restoring River Herring Habitat Connectivity

In combination with pollution reduction and riparian habitat restoration and conservation actions,

NFWF will increase connectivity and access to spawning habitat along priority migratory corridors for

alewife and blueback herring through dam removal, repair and replacement of culverts and road

crossings, and other fish passage improvements. NFWF will prioritize cost-effective connectivity

enhancements that provide the access to the greatest amount of quality habitat at the lowest cost.

3.3 Restoring and Conserving Wetland and Tidal Marsh Habitat for American Black Duck

Wetlands and tidal marshes in the Chesapeake Bay’s Coastal Plain region provide critical habitat to

wintering populations of American black duck. NFWF will help to increase winter food supplies for these

and other migratory waterfowl species both by restoring degraded tidal and non-tidal marsh and

wetland habitats and by conserving existing high quality winter habitats. To address threats to habitat

from sea level rise, NFWF will further support strategies that seek create corridors for future marsh

migration through strategic land protection, restoration, and management.

3.4 Managing Shoreline Erosion and Marsh Loss

Shorelines and nearshore marshes in the Chesapeake Bay estuary act as important nursery and rearing

habitat for aquatic species and serve as a buffer against erosive wind and wave action. Unfortunately,

shorelines in the Chesapeake Bay region are eroding at a dramatic rate.

3

NFWF will support non-

structural or hybrid living shoreline restoration practices that mitigate sediment transport to priority

oyster reef restoration sites, establish and expand emergent or submerged aquatic vegetation, and/or

help to protect adjacent marsh systems documented as critical black duck wintering habitat.

Strategy 4: Building Capacity for Landscape-Scale Watershed and Habitat Outcomes

4.1 Regional-Scale Partnership Development

With nearly 40 years of coordinated, local efforts to restore and protect the Chesapeake Bay, partners

from all sectors across the region need new tools and resources to expand partnerships, programs, and

3

Schieder, N.W., Walters, D.C., & Kirwan, M.L. (2018). Massive upland to wetland conversion compensated for

historical marsh loss in Chesapeake Bay, USA. Estuaries and Coasts 40: 940-951.

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 13

implementation strategies to meet ambitious goals of the Chesapeake Bay TMDL and the Chesapeake

Bay Watershed Agreement. NFWF will invest in activities that aim to scale up restoration outcomes

through enhanced partnership and coordination across organizations at broader regional and landscape

scales, especially those working through institutional mechanisms like Memoranda of Agreement,

organizational mergers, etc. Examples of specific activities include:

Developing or refining a collaborative strategic plan or financing strategy;

Investigating and evaluating the potential for organizational collaboration, with the goal of

developing a sustainable network or integrating or merging existing organizations;

Improving processes for internal communications, operations, management, and fundraising in

support of restoration activities;

Developing or enhancing cooperative programming for funding, technical support, project

identification and prioritization, planning, procurement and purchasing, project management,

and other functions directly related to implementation;

Developing venues for collaborating practitioners to share case studies, lessons learned, credible

guidance, and other resources in support of restoration activities.

4.2 Improving Delivery of Outreach and Technical Assistance

With a significant portion of land in the Chesapeake Bay watershed in private ownership, resources for

education, outreach and technical assistance are critical in recruiting urban, suburban, and agricultural

landowners to adopt conservation practices and for providing assistance with the planning, design,

implementation, and maintenance of those practices over time. NFWF will support conservation

districts, nonprofits, local and state governments, and private sector partners to provide technical

assistance necessary to achieve NFWF’s habitat restoration, conservation, and management goals.

Funding will support field positions, development of targeted outreach strategies such as community-

based social marketing, and enhanced coordination and partnership among technical assistance

providers to improve efficiency and reduce administrative bottlenecks.

Strategy 5: Watershed and Habitat Planning, Prioritization, Design, and Permitting

5.1 Assessing Local Watershed and Habitat Restoration Needs and Opportunities

While this Business Plan identifies watershed-scale needs and opportunities, NFWF recognizes that local

conditions can dramatically impact where and how work can be done to maximize conservation

outcomes. NFWF will provide resources to help local partners conduct watershed and habitat

assessments, watershed implementation planning, and other planning and prioritization efforts to

maximize conservation impact. Priority will be placed on efforts to translate Bay pollution reduction

goals to local implementation plans, along with efforts to identify habitat restoration opportunities for

NFWF’s priority species at a local level. Examples include property or farm-level conservation and

stormwater management plans, patch-level population and habitat assessments for Eastern brook trout,

culvert and barrier assessments in priority rivers for river herring, and wetlands restoration and

protection assessments to maximize black duck population outcomes.

5.2 Designing and Permitting Watershed and Habitat Improvements

Watershed and habitat restoration and management actions often require detailed technical analyses

and designs in order to maximize outcomes and obtain necessary permits for implementation. NFWF

will strategically assist local partners with costs associated with design and permitting for high-impact

restoration and management actions.

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 14

Figure 9. Logic model depicting how business plan strategies are anticipated to lead to intermediate results and ultimately to the Chesapeake

Bay business plan goals.

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 15

Risk Assessment

Risk is an uncertain event or condition which, if it occurs, could impact a program’s desired outcome. In

consultation with external experts, NFWF assessed seven risk categories to determine the extent to

which they could impede progress towards our stated Business Plan strategies and goals during the next

10 years. Below, we identify the greatest potential risks to success and describe strategies that we will

implement to minimize or avoid those risks, where applicable.

RISK

CATEGORY

RISK

RATING

RISK DESCRIPTION

MITIGATING STRATEGIES

Regulatory Risks

Low

The Chesapeake Bay TMDL provides a regulatory

framework to advance water quality goals,

though inconsistent enforcement of state and

local standards may limit incentives to

implement necessary improvements.

Inconsistent fisheries management and stocking

practices may further limit range-wide goals.

Not addressed in plan.

Financial Risks

High

Heavy reliance on a single funder for a majority

of program funds presents inherent

vulnerabilities. Inconsistent state and local

funding across the watershed also limits

potential for leveraging of NFWF funding.

Necessary funds for ongoing maintenance of

funded efforts are unidentified.

Budget plan includes development

and fundraising strategies to diversify

programmatic funding sources. Long-

term maintenance of restoration

investments is a priority for leveraged

funding.

Environmental

Risks

Medium

Anticipated changes in hydrologic regimes may

make it more difficult to manage and limit

polluted runoff and erosive stormwater flows.

Increased temperatures and sea level rise may

contribute to increased shoreline and marsh

erosion and stress for freshwater species.

Contamination from toxic chemicals and

development may further stress target species.

Large-scale hydrologic modifications

will be limited to areas with effective

upland stormwater controls.

Freshwater conservation strategies

will focus on securing high quality

habitat at lower risk to change.

Shoreline restoration strategies target

efforts to protect existing high quality

habitats.

Scientific Risks

Low

Lack of scientific consensus on achievable goals

for targeted species and specific and measurable

benefits to species of proposed interventions.

Targeted investments in monitoring

and assessment will fill key

informational gaps.

Social Risks

Low

Social factors can impact the willingness of

landowners to implement proposed

interventions. Demographic changes and urban

development may require tailored approaches

for new communities and stakeholders.

Outreach and technical assistance

strategies support initiatives to

inform local efforts with social

science principles.

Economic Risks

Medium

Highly variable agricultural commodity and input

prices may impact ability of producers to cost-

share necessary interventions. Economic

incentives may place increasing development

pressure on key resource areas.

Agricultural water quality strategies

aim to support approaches that

provide economic returns to

producers. Strategies to support

conservation of priority areas may

limit risk of development.

Institutional

Risks

High

Lack of effective coordination among local

restoration partners may cause inefficiencies and

unintended consequences.

Plan strategies for regional-scale

partnership development support

collaborative and integrated

approaches to restoration.

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 16

Monitoring & Evaluating Performance

Performance of the Stewardship Fund will be assessed at both project and program scales. At the

project scale, individual grants will be required to track relevant metrics from Table 2 for demonstrating

progress on project activities and outcomes, and to report on them in their interim and final

programmatic reports. At the program scale, broader habitat and species outcomes will be monitored

through targeted grants, existing external data sources, and aggregated data from relevant grant

projects, as appropriate. In addition, NFWF may conduct internal assessments and commission third-

party evaluations in the future to determine program outcomes and adaptively manage.

To enhance the quality and consistency of grantee reporting for performance monitoring and

evaluation, NFWF will utilize the FieldDoc platform to collect geographically explicit, hierarchical data on

NFWF-funded activities at the practice, site, and project level. FieldDoc captures local factors (hydrology,

topography, soil type, etc.), robust information on the types of conservation practices implemented, and

ongoing practice monitoring data, allowing for the application of environmental models that can

consistently translate grantee-reported information into estimates of conservation outcome. Current

FieldDoc functionality allows for the estimation of nutrient and sediment reduction benefits consistent

with the methods and models used by EPA for regulatory purposes. Additional functionality and models

will be incorporated in the short term to build FieldDoc’s capacity to estimate modeled species and

habitat outcomes.

In cases where modeled conservation outcomes via FieldDoc are NFWF’s primary source of performance

data, NFWF will fund targeted field-based monitoring to validate modeled outcomes at regular intervals.

Category

Strategies and Outcomes

Metrics

Baseline

(2012)

Progress

(2018)

Goal

(2025)

Data source(s)

Water Quality

Reduce nitrogen pollution

Pounds of nitrogen

pollution reduced

annually (lbs/yr)

0

7M

10M

FieldDoc

(modeled pollutant

reductions)

Reduce phosphorus pollution

Pounds of phosphorus

pollution reduced

annually (lbs/yr)

0

550,000

1M

FieldDoc

(modeled pollutant

reductions)

Reduce sediment pollution

Pounds of sediment

pollution reduced

annually (lbs/yr)

0

124M

200M

FieldDoc

(modeled pollutant

reductions)

Implement best management

practices to reduce polluted

runoff

Acres of BMPs

implemented

0

495,376

1M

Grantee reporting

Implement green stormwater

infrastructure practices

Gallons of stormwater

capture and runoff

reduction from installed

infrastructure

0

TBD

150M

FieldDoc

(modeled volume

reductions)

Restore 1,000 miles of

riparian forest buffer

Miles of riparian habitat

restored

0

462

1,000

Grantee reporting,

validated by site-

level functional

assessments

Improve health and function

of 1,500 stream miles

Miles of healthy,

functioning stream

0

508

1,500

Grantee reporting,

validated by

independent

stream biota

monitoring

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 17

Eastern brook

trout

Increase populations in 6

stronghold patches

Number of effective

breeders

0

0

6

Independent EBT

population

monitoring

Increase habitat integrity in 6

occupied patches

Number of patches with

improved habitat

integrity

0

0

6

Grantee reporting,

validated by

independent EBT

population

monitoring

Eastern oyster

Restore native Eastern oyster

habitat and populations in 5

Chesapeake Bay tributaries

Number of tributaries

with restored oyster

populations

0

2

5

Chesapeake Bay

Program’s existing

monitoring efforts

Restore 250 acres of native

oyster reefs within targeted

tributaries

Acres of oyster reef

restored

0

142

250

Grantee reporting,

validated by

Chesapeake Bay

Program

monitoring

American

black duck

Increasing wetland habitat

and available food to support

5,000 wintering black ducks

Number of black duck

utilizing wetland

restoration sites

0

0

5,000

Independent duck

use monitoring

Create, reestablish, or

enhance the function of 7,000

acres of tidal and non-tidal

wetlands

Acres of wetland

restored

0

965

7,000

FieldDoc

Increase available food

resources by 680 million

kilocalories

Kilocalories of black

duck food resources

0

0

680

million

FieldDoc,

supported by

estimates of

energy value by

wetland type

River herring

Increase river herring

presence in 200 additional

miles of high quality

migratory habitat

Miles of stream opened

0

13

200

FieldDoc, validated

by independent

occurrence

monitoring

Implement 10 connectivity

enhancement projects

Number of barriers

rectified

0

0

10

Grantee reporting

Capacity and

planning

Motivate 20,000 individuals

to adopt conservation

behaviors

Number of individuals

demonstrating changed

behavior

0

21,257

40,000

Grantee reporting

Enlist 25,000 in local

volunteer events

Number of volunteers

participating

0

10,099

25,000

Grantee reporting

Develop or improve 1,000

conservation, watershed, or

habitat management plans

Number of plans

developed or improved

0

118

1,000

Grantee reporting

Table 2. Program Metrics

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 18

Budget

This Business Plan update comes seven years into NFWF’s Business Plan-focused investing in

Chesapeake Bay restoration efforts. Based on 2012 projections of a 14-year, $100 million budget, NFWF

is well on track with anticipated spending towards Plan outcomes with roughly $59.8 million spent to

date on activities half way through the Chesapeake Bay Business Plan.

The following budget shows the estimated total costs to implement the revised set of Business Plan

activities set forth in this updated document, including activities initiated and already funded since

2012. NFWF will have to raise funds to meet these costs; therefore, this budget reflects NFWF’s

anticipated engagement over the Business Plan period of performance and it is not an annual or even

cumulative commitment by NFWF to invest. This budget assumes that current activities funded by

others will, at a minimum, continue.

BUDGET CATEGORY

Total

Strategy 1. Managing Agricultural and Urban Runoff

1.1 Managing Agricultural Runoff

$30.00M

1.2 Managing Urban Runoff

$10.00M

1.3 Accelerating Innovation

$2.50M

Strategy 2. Riparian and Freshwater Habitat Restoration, Conservation, and Management

2.1 Restoring Riparian and Freshwater Habitats

$30.00M

2.2 Increasing Connectivity and Occupied Habitat

$0.50M

2.3 Improving Riparian Management

$5.00M

2.4 Conserving Riparian Corridors

$0.50M

Strategy 3. Estuarine and Tidal Habitat Restoration, Conservation, and Management

3.1 Restoring Oyster Reefs

$2.00M

3.2 Restoring Migratory Fish Habitat

$0.75M

3.3 Restoring and Conserving Wetland and Marsh Habitat

$2.75M

3.4 Managing Shoreline Erosion and Marsh Loss

$1.00M

Strategy 4. Building Capacity for Landscape-Scale Watershed and Habitat Outcomes

4.1 Regional-Scale Partnership Development

$5.00M

4.2 Improving Outreach and Technical Assistance

$5.00M

Strategy 5. Watershed and Habitat Planning, Prioritization, Design, and Permitting

5.1 Watershed and Habitat Assessment

$1.25M

5.2 Design and Permitting Watershed and Habitat Improvements

$1.00M

Monitoring and Assessment

$2.75M

TOTAL BUDGET

$100.00M

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 19

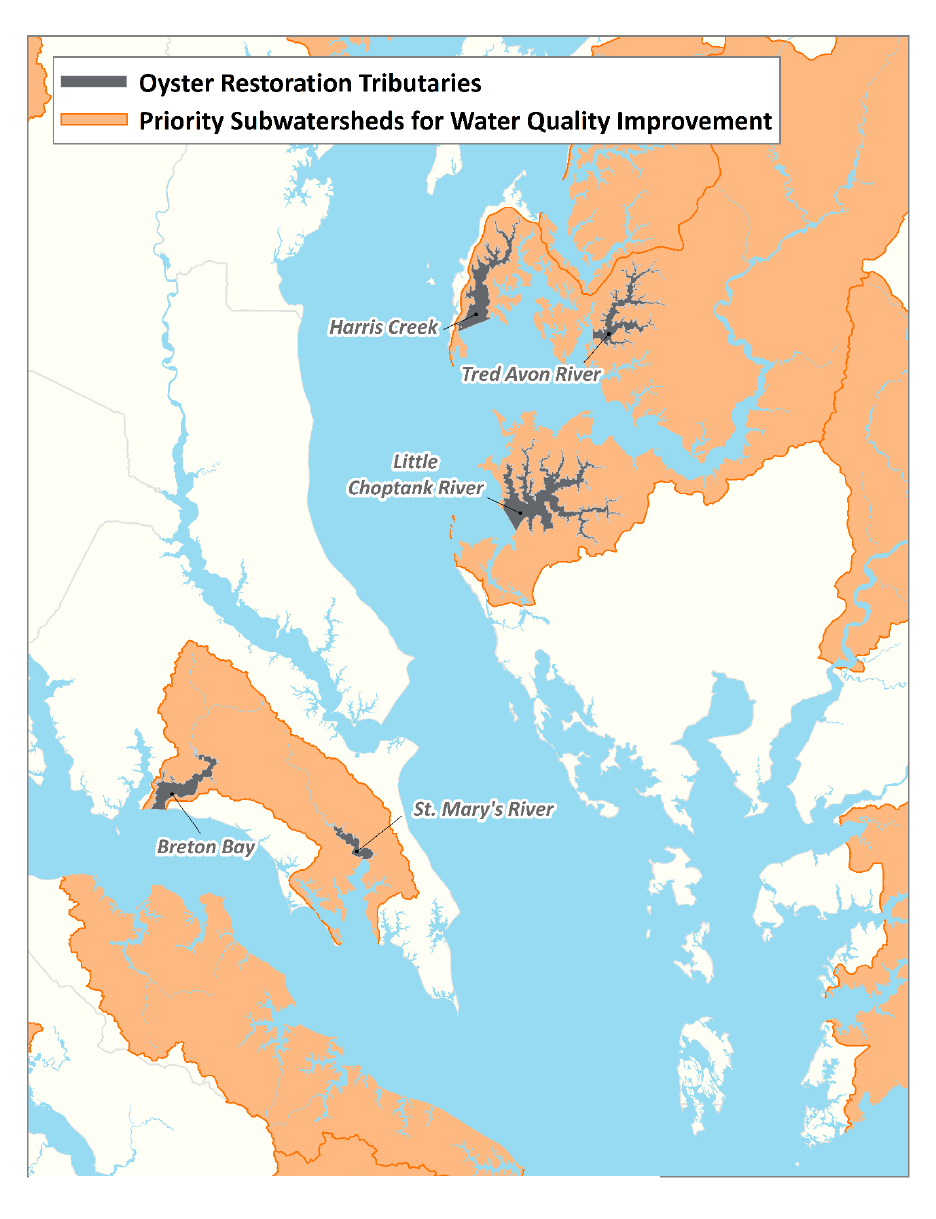

Appendix A. Geographic Focus Areas

Figure 1. Priority Subwatersheds for Water Quality Improvement

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 20

Figure 2. Stronghold Patches for Brook Trout Population Increase

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 21

Figure 3. Priority Subwatersheds for Black Duck

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 22

Figure 4. Priority Culverts for River Herring, Choptank River (MD)

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 23

Figure 5. Priority Culverts for River Herring, Nanticoke River (MD)

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 24

Figure 6. Priority Culverts for River Herring, James River (VA)

Chesapeake Bay Stewardship Fund | 25

Figure 7. Oyster Restoration Tributaries (MD)