THE WILLIAM J. BAUER

PATTERN CRIMINAL

JURY INSTRUCTIONS

OF THE SEVENTH

CIRCUIT

(2023 Ed.)

Prepared by

The Committee on Federal Criminal Jury Instructions

of the Seventh Circuit

For Customer Assistance Call 1-800-328-4880

Mat #43239089

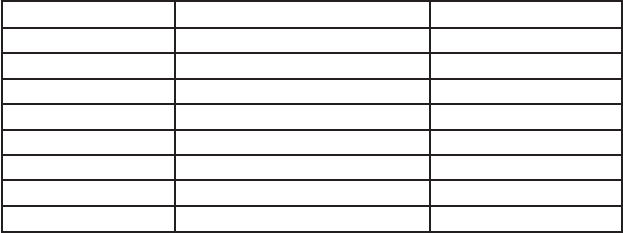

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PRELIMINARY INSTRUCTIONS—FOR USE AT THE

BEGINNING OF TRIAL

Instruction Page

Functions of Court and Jury ........................................6

The Charge............................................................8

Presumption of Innocence/Burden of Proof........................9

The Evidence ........................................................10

Testimony Presented Through Interpreter.......................11

Direct and Circumstantial Evidence..............................12

Considering the Evidence ..........................................13

Credibility of Witnesses ............................................14

Number of Witnesses ...............................................15

Juror Note-Taking ..................................................16

Juror Conduct .......................................................17

Conduct of the Trial ................................................19

GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS

1.01 Functions of Court and Jury..................................20

1.02 The Charge .....................................................22

1.03 Presumption of Innocence/Burden of Proof..................24

1.04 Definition of Reasonable Doubt ..............................26

1.05 Definition of Crime Charged..................................27

1.06 Definition of Felony/Misdemeanor ...........................28

1.07 Bill of Particulars ..............................................29

2.01 The Evidence ...................................................30

2.02 Considering the Evidence .....................................32

2.03 Direct and Circumstantial Evidence .........................33

2.04 Number of Witnesses ..........................................34

2.05 Defendant’s Decision Not to Testify or Present Evidence .35

3.01 Credibility of Witnesses .......................................36

3.02 Attorney Interviewing Witness ...............................38

3.03 Prior Inconsistent Statements ................................39

3.04 Prior Inconsistent Statement by Defendant ................40

vii

Instruction Page

3.05 Witnesses Requiring Special Caution........................41

3.06 Impeachment by Prior Conviction ............................43

3.07 Character Evidence Regarding Witness .....................44

3.08 Character Evidence Regarding Defendant ..................45

3.09 Statement by Defendant ......................................46

3.10 Defendant’s Silence in the Face of Accusation ..............48

3.11 Evidence of Other Acts by Defendant........................49

3.12 Identification Testimony.......................................52

3.13 Opinion Testimony .............................................54

3.13(a) Dual-Capacity Witness Testimony ........................55

3.14 Recorded Conversations/Transcripts .........................57

3.15 Foreign Language Recordings/English Transcripts ........59

3.16 Summaries Received in Evidence ............................60

3.17 Demonstrative Summaries/Charts Not Received in

Evidence ...................................................61

3.18 Juror Note-Taking .............................................62

3.19 Government Investigative Techniques .......................63

4.01 Burden of Proof—Elements ...................................65

4.02 Burden of Proof in Case Involving Insanity

Defense—Elements ........................................66

4.03 Burden of Proof in Case Involving Coercion

Defense—Elements ........................................68

4.04 Unanimity on Specific Acts ...................................70

4.05 Date of Crime Charged ........................................73

4.06 Separate Consideration—One Defendant Charged with

Multiple Crimes............................................74

4.07 Separate Consideration—Multiple Defendants Charged

with Same or Multiple Crimes ...........................75

4.08 Punishment .....................................................76

4.09 Attempt .........................................................77

4.10 Definition of Knowingly .......................................80

4.11 Definition of Willfully..........................................82

4.12 Specific Intent/General Intent ................................83

4.13 Definition of Possession .......................................84

4.14 Possession of Recently Stolen Property......................85

5.01 Responsibility ...................................................86

5.02 Personal Responsibility of Corporate Agent.................87

5.03 Entity Responsibility—Entity Defendant—Agency.........88

5.04 Entity Responsibility—Entity Defendant—Agency

Ratification .................................................92

5.05 Joint Venture ...................................................93

5.06 Aiding and Abetting/Acting Through Another ..............94

5.06(A) Aiding and Abetting ........................................95

5.06(B) Acting Through Another ...................................96

5.07 Presence/Activity/Association .................................99

viii

Instruction Page

5.08(A) Conspiracy—Overt Act Required ........................102

5.08(B) Conspiracy—No Overt Act Required ....................105

5.09 Conspiracy—Definition of Conspiracy ......................107

5.10 Conspiracy—Membership in Conspiracy...................109

5.10(A) Buyer/Seller Relationship ................................111

5.10(B) Single Conspiracy vs. Multiple Conspiracies...........113

5.11 Conspirator’s Liability for Substantive Crimes Committed

by Co-Conspirators Where Conspiracy

Charged—Elements......................................115

5.12 Conspirator’s Liability for Substantive Crimes Committed

by Co-Conspirators; Conspiracy Not Charged in the

Indictment—Elements...................................117

5.13 Conspiracy—Withdrawal ....................................119

5.14(A) Conspiracy—Withdrawal—Statute of

Limitations—Elements...............................122

5.14(B) Conspiracy—Withdrawal—Statute of Limitations.....124

6.01 Self Defense/Defense of Others .............................126

6.02 Insanity ........................................................128

6.03 Defendant’s Presence.........................................130

6.04 Entrapment—Elements ......................................131

6.05 Entrapment—Definitions of Terms .........................132

6.06 Reliance on Public Authority ................................136

6.07 Entrapment by Estoppel .....................................138

6.08 Coercion/Duress...............................................140

6.09(A) Voluntary Intoxication ....................................141

6.09(B) Diminished Capacity......................................142

6.10 Good Faith—Fraud/False

Statements/Misrepresentations.........................143

6.11 Good Faith—Tax and Other Technical Statute Cases . . ..145

6.12 Reliance on Advice of Counsel...............................146

7.01 Jury Deliberations............................................147

7.02 Verdict Form ..................................................149

7.03 Unanimity/Disagreement Among Jurors ...................150

STATUTORY INSTRUCTIONS

7 U.S.C. § 2024(b) Unauthorized Acquisition of Food

Stamps—Elements .............................................152

7 U.S.C. § 2024(b) Definition of “Contrary to Law”............154

8 U.S.C. § 1324a(a)(1)(A) Unlawful Employment—Elements.155

8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(1)(A)(i) Bringing Alien to the United States

Other than at Designated Place—Elements .................157

8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(1)(A)(ii) Alien Transportation—Elements.160

8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(1)(A)(iii) Concealing or Harboring

Aliens—Elements ...............................................163

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ix

Instruction Page

8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(1)(A)(iv) Encouraging Illegal

Entry—Elements ...............................................166

8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(2)(B)(ii) Bringing Alien into United States

for Commercial Advantage or Private Financial

Gain—Elements.................................................168

8 U.S.C. § 1324(a)(2)(B)(iii) Bringing Alien into United States

Without Immediate Presentation at Designated Port of

Entry—Elements ...............................................171

8 U.S.C. § 1325(a)(1) Illegal Entry—Elements .................174

8 U.S.C. § 1325(a)(2) Eluding Examination or

Inspection—Elements ..........................................176

8 U.S.C. § 1325(a)(3) Entry by False or Misleading

Representation—Elements ....................................178

8 U.S.C. § 1325(c) Marriage Fraud—Elements ................180

8 U.S.C. § 1326(a) Deported Alien Found in United

States—Elements ...............................................182

8 U.S.C. § 1546(a) Use, Possession of Immigration Document

Procured by Fraud—Elements ................................184

18 U.S.C. § 3 Accessory After the Fact..........................186

18 U.S.C. § 111(a) Assaulting a Federal Officer—Elements . .188

18 U.S.C. §§ 111(a) & 111(b) Definition of “Assault”...........190

18 U.S.C. §§ 111(a) & 111(b) Definition of “Forcibly” ..........191

18 U.S.C. § 111(b) Assaulting a Federal Officer Using a Deadly

or Dangerous Weapon or Inflicting Bodily

Injury—Elements ...............................................192

18 U.S.C. § 111(b) Definition of “Bodily Injury” ................194

18 U.S.C. § 111(b) Definition of “Deadly or Dangerous

Weapon”..........................................................195

18 U.S.C. § 115(a)(1)(B) Definition of “Threaten” ..............196

18 U.S.C. § 115(a)(1)(B) Threatening A United States Official,

United States Judge, or Federal Law Enforcement

Officer—Elements ..............................................197

18 U.S.C. § 115(c)(1) Definition of “Federal Law Enforcement

Officer” ...........................................................199

18 U.S.C. § 115(c)(3) Definition of “United States Judge”.....200

18 U.S.C. § 115(c)(4) Definition of “United States Official” ...201

18 U.S.C. § 152(1) Concealment of Property—Elements ......202

18 U.S.C. § 152(1) Definition of “Concealment” ................204

18 U.S.C. § 152(2) & (3) False Oath, False Declaration under

Penalty of Perjury—Elements.................................205

18 U.S.C. § 152(2) & (3) False Declaration under Penalty of

Perjury—Definition of Materiality ............................207

18 U.S.C. § 152(4) Presenting or Using a False

Claim—Elements ...............................................208

18 U.S.C. § 152(6) Bribery—Elements ..........................209

18 U.S.C. § 152(7) Concealment or Transfer of Assets in

x

Instruction Page

Contemplation of Bankruptcy or with Intent to Defeat the

Provisions of the Bankruptcy Law—Elements ..............235

18 U.S.C. § 152(7) Definition of “In Contemplation of a

Bankruptcy Proceeding” .......................................212

18 U.S.C. § 152(7) Definition of “Transfer” .....................213

18 U.S.C. § 152(8) Destruction of Records; False

Entries—Elements..............................................214

18 U.S.C. § 152(9) Withholding Records—Elements...........215

18 U.S.C. § 201 Intent to Influence..............................216

18 U.S.C. § 201 Definition of “Official Act” .....................217

18 U.S.C. § 201(b)(1)(A) Giving a Bribe—Elements ...........220

18 U.S.C. § 201(b)(2)(A) Accepting a Bribe—Elements........222

18 U.S.C. § 241 Conspiracy Against Civil Rights—Elements.225

18 U.S.C. § 241 Definition of Constitutional Rights ...........227

18 U.S.C. § 241 Death ............................................228

18 U.S.C. § 242 Deprivation of Rights under Color of

Law—Elements .................................................232

18 U.S.C. § 242 Deprivation of Rights under Color of Law—

Definition of Intentionally .....................................234

18 U.S.C. § 242 Deprivation of Rights under Color of Law—

Definition of Intentionally—For Use in Excessive Force

Cases .............................................................235

18 U.S.C. § 242 Definition of Constitutional Rights ...........236

18 U.S.C. § 242 Definition of “Color of Law” ...................237

18 U.S.C. § 242 Death ............................................238

18 U.S.C. § 242 Definition of “Bodily Injury”...................239

18 U.S.C. § 286 Conspiracy to Defraud the Government with

Respect to Claims—Elements .................................241

18 U.S.C. § 287 False, Fictitious, or Fraudulent

Claims—Elements ..............................................243

18 U.S.C. § 401 Criminal Contempt.............................246

18 U.S.C. § 402 Criminal Contempt.............................247

18 U.S.C. § 471 Falsely Making, Forging, Counterfeiting, or

Altering a Security or Obligation—Elements................248

18 U.S.C. § 472 Uttering Counterfeit Obligations or

Securities—Elements...........................................250

18 U.S.C. § 473 Dealing in Counterfeit Obligations or

Securities—Elements...........................................252

18 U.S.C. § 495 Falsely Making, Forging, Counterfeiting, or

Altering a Document—Elements..............................253

18 U.S.C. § 495 Uttering or Publishing a False

Document—Elements ..........................................255

18 U.S.C. § 495 Presenting a False Document—Elements . . .257

18 U.S.C. § 500 Falsely Making, Forging, Counterfeiting,

Engraving, or Printing a Money Order—Elements .........259

18 U.S.C. § 500 Forging or Counterfeiting a Signature or

TABLE OF CONTENTS

xi

Instruction Page

Initials of Any Person Authorized to Issue a Money Order,

Postal Note, or Blank—Elements .............................277

18 U.S.C. § 500 Forging or Counterfeiting a Signature or

Endorsement on a Money Order, Postal Note, or

Blank—Elements ...............................................264

18 U.S.C. § 500 Forging or Counterfeiting a Signature on a

Receipt or Certificate of Identification—Elements ..........266

18 U.S.C. § 500 Falsely Altering a Money Order or Postal

Note—Elements.................................................268

18 U.S.C. § 500 Passing, Uttering, or Publishing Forged or

Altered Money Orders or Postal Notes—Elements .........269

18 U.S.C. § 500 Fraudulently Issuing a Money Order or Postal

Note—Elements.................................................271

18 U.S.C. § 500 Theft of a Money Order—Elements ..........273

18 U.S.C. § 500 Receipt or Possession of a Stolen Money

Order—Elements ...............................................274

18 U.S.C. § 500 False Presentment of a Money Order or Postal

Note—Elements.................................................275

18 U.S.C. § 500 Theft or Receipt of a Money Order Machine or

Instrument—Elements .........................................277

18 U.S.C. § 500 Definition of “Material” ........................279

18 U.S.C. § 500 Definition of “Material Alteration”............280

18 U.S.C. § 511 Altering or Removing Vehicle Identification

Numbers .........................................................281

18 U.S.C. § 542 Entry of Goods by Means of False

Statements—Elements .........................................282

18 U.S.C. § 542 Entry of Goods by Means of False

Statements—Definition of “Fraudulent” .....................284

18 U.S.C. § 542 Definition of “Material” ........................285

18 U.S.C. § 542 Entry of Goods by Means of False

Statements—Definition of Entry..............................286

18 U.S.C. § 542 Entry of Goods by Means of False

Statements—Definition of Imported Merchandise ..........287

18 U.S.C. § 542 Entry of Goods by Means of False

Statements—United States Has Been or May Have Been

Deprived of Any Lawful Duties—Elements ..................288

18 U.S.C. § 641 Theft of Government Property—Elements. . .289

18 U.S.C. § 641 Definition of “Value”............................291

18 U.S.C. § 659 Embezzlement or Theft of Goods from

Interstate Shipment—Elements ..............................292

18 U.S.C. § 659 Possession of Goods Stolen from Interstate

Shipment—Elements ...........................................294

18 U.S.C. § 666(a)(1)(A) Theft Concerning Federally Funded

Program—Elements ............................................296

DELETED ..........................................................298

xii

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 666(a)(1)(B) Accepting a Bribe—Elements........300

18 U.S.C. § 666(a)(2) Paying a Bribe—Elements ..............304

18 U.S.C. § 666(c) Bona Fide Compensation ...................308

18 U.S.C. § 666 Definition of “Agent” ...........................309

18 U.S.C. § 669(a) Health Care Theft or

Embezzlement—Elements .....................................310

18 U.S.C. § 669(a) Definition of “Health Care Benefit

Program”.........................................................312

18 U.S.C. § 751 Escape—Elements ..............................313

18 U.S.C. § 842(a)(1) Importing, Manufacturing, or Dealing in

Explosive Materials Without a License—Elements .........314

18 U.S.C. § 842(a)(2) Withholding Information, Making a False

Statement, or Furnishing False Identification to Obtain

Explosive Materials—Elements ...............................316

18 U.S.C. § 875(a) Transmission of a Ransom or

Reward—Elements .............................................318

18 U.S.C. § 875(b) Transmission of an Extortionate Threat to

Kidnap or Injure a Person—Elements .......................320

18 U.S.C. § 875(c) Transmission of a Threat to Kidnap or

Injure—Elements ...............................................322

18 U.S.C. § 875(d) Transmission of an Extortionate Threat to

Property or Reputation—Elements ...........................324

18 U.S.C. § 876(a) Mailing a Demand for Ransom or

Reward—Elements .............................................326

18 U.S.C. § 876(b) Mailing an Extortionate Threat to Kidnap or

Injure—Elements ...............................................327

18 U.S.C. § 876(c) Mailing a Threat to Kidnap or

Injure—Elements ...............................................329

18 U.S.C. § 876(d) Mailing an Extortionate Threat to

Reputation—Elements .........................................331

Definition of “True Threat” .......................................333

Definition of “Intent to Extort”...................................335

18 U.S.C. § 892 Extortionate Extension of

Credit—Elements...............................................336

18 U.S.C. § 892 Definition of “Debtor” ..........................338

18 U.S.C. § 892 Definition of Understanding...................339

18 U.S.C. § 894 Extortionate Collection of Debt—Elements..340

18 U.S.C. § 894 Definition of “Extortionate Means” ...........342

Forfeiture—Third Party Interests ...............................343

18 U.S.C. § 911 Representation of Citizenship of United

States—Elements ...............................................344

18 U.S.C. § 912 Impersonation of an Officer or Employee of the

United States ...................................................347

18 U.S.C. § 922 Definition of “Ammunition”....................350

18 U.S.C. § 922(a)(6) Making a False Statement or Furnishing

False Identification to a Licensed Firearms Importer,

TABLE OF CONTENTS

xiii

Instruction Page

Manufacturer, Dealer, or Collector in Connection with the

Acquisition of a Firearm or Ammunition—Elements .......366

18 U.S.C. § 922(d) Sale or Transfer of a Firearm or

Ammunition to a Prohibited Person—Elements ............353

18 U.S.C. § 922(d) Definition of “Reasonable Cause to

Believe” ..........................................................355

18 U.S.C. § 922(g) Definitions of “In or Affecting Commerce”

and “In Interstate or Foreign Commerce”....................356

18 U.S.C. § 922(g) Definition of “Possession”...................358

18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(1) Unlawful Shipment or Transportation of a

Firearm or Ammunition by a Convicted Felon—Elements.359

18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(1) Unlawful Possession or Receipt of a

Firearm or Ammunition by a Prohibited

Person—Elements ..............................................361

18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(3) Definition of “Unlawful User” ...........363

18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(3) Unlawful Shipment or Transportation of a

Firearm or Ammunition by an Unlawful User or Addict of a

Controlled Substance—Elements .............................364

18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(3) Unlawful Possession or Receipt of a

Firearm or Ammunition by an Unlawful User or Addict of a

Controlled Substance—Elements .............................366

18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(5) Definition of “Alien Illegally or

Unlawfully in the United States” .............................368

18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(5) Unlawful Possession or Receipt of a

Firearm or Ammunition by an Alien Illegally or Unlawfully

in the United States—Elements ..............................369

18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(5) Unlawful Shipment or Transportation of a

Firearm or Ammunition by an Alien Illegally or Unlawfully

in the United States—Elements ..............................371

Definition of “True Threat” .......................................373

Definition of “Intent to Extort”...................................375

18 U.S.C. §§ 922 & 924 Definition of “Firearm” ...............376

18 U.S.C. §§ 922 & 924 Definition of “Antique Firearm” .....377

18 U.S.C. §§ 922 & 924 Brandish/Discharge Special Verdict

Instructions—Definition of “Brandish” .......................378

18 U.S.C. § 924(c) Definition of “Use” ...........................380

18 U.S.C. § 924(c) Definition of “Carry”.........................381

18 U.S.C. § 924(c) Definition of “During” .......................382

18 U.S.C. § 924(c) Definition of “In Relation To”...............383

18 U.S.C. § 924(c) Definition of “In Furtherance Of” ..........384

18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A) Using or Carrying a Firearm During

and in Relation to a Crime of Violence or Drug Trafficking

Crime—Elements ...............................................386

18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A) Using or Carrying a Firearm During

and in Relation to a Crime of Violence or Drug Trafficking

Crime—Accountability Theory Elements ....................388

xiv

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A) Possession of a Firearm in Furtherance

of a Crime of Violence or Drug Trafficking

Crime—Elements ...............................................390

18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A) Possession of a Firearm in Furtherance

of a Crime of Violence or Drug Trafficking Crime—

Accountability Theory Elements ..............................392

18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A) Definition of “Advance Knowledge” .393

18 U.S.C. § 981(a)(1)(A) Forfeiture Instruction ................395

18 U.S.C. § 981(a)(1)(C) Forfeiture Instruction—Elements . ..398

18 U.S.C. § 981(a)(1)(G)(i–iii) Forfeiture

Instruction—Elements .........................................402

18 U.S.C. § 981(a)(1)(G)(iv) Forfeiture

Instruction—Elements .........................................405

18 U.S.C. § 981(a)(1)(H) Forfeiture Instruction—Elements.. .407

18 U.S.C. § 981(a)(2) Definition of “Proceeds” ..................409

18 U.S.C. § 981(a)(2) Definition of ‘‘Traceable To’’ .............411

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(1) Forfeiture Instruction....................412

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(2) Forfeiture Instruction....................414

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(3) Forfeiture Instruction....................417

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(4) Forfeiture Instruction....................420

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(5) Forfeiture Instruction....................423

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(6) Forfeiture Instruction....................425

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(7) Forfeiture Instruction....................428

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(8) Forfeiture Instruction....................430

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(8) Definition of “Nexus” Instruction .......432

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(8) Definition of Federal “Health Care Fraud

Offense” ..........................................................433

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(8) Definition of “Conveyance” ..............435

18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(8) Property Subject to Forfeiture ..........436

18 U.S.C. § 1001 Definition of False or Fictitious .............437

18 U.S.C. § 1001 Definition of Fraudulent......................438

18 U.S.C. § 1001 Definition of “Material”.......................439

18 U.S.C. § 1001 Definition of “Willfully”.......................440

18 U.S.C. § 1001 Department or Agency........................441

18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(1) Concealing a Material

Fact—Elements .................................................442

18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(1) Definition of “Trick, Scheme, or

Device” ...........................................................444

18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(2) Making a False Statement or

Representation—Elements ....................................445

18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(3) Making or Using a False Writing or

Document—Elements ..........................................447

18 U.S.C. § 1005 Fraudulently Benefitting from a Loan by a

Federally Insured Institution—Elements ....................449

18 U.S.C. § 1006 Insider Fraud on a Federally Insured

Financial Institution—Elements

..............................450

TABLE OF CONTENTS

xv

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 1007 False Statements to Influence the

FDIC—Elements................................................452

18 U.S.C. § 1014 False Statement to Financial

Institution—Elements..........................................453

18 U.S.C. § 1015(a) Making a False Statement in an

Immigration Document—Elements ...........................455

18 U.S.C. § 1015(b) False Denial of Naturalization or

Citizenship—Elements .........................................456

18 U.S.C. § 1015(c) Use of Fraudulent Immigration

Document—Elements ..........................................457

18 U.S.C. § 1015(d) Making False Certificate of

Appearance—Elements ........................................458

18 U.S.C. § 1015(e) False Claim of Citizenship—Elements. . .460

18 U.S.C. § 1015(f) False Claim of Citizenship in Order to

Vote—Elements .................................................461

18 U.S.C. § 1028 Penalty-Enhancing Instructions and Special

Verdict Forms ...................................................462

18 U.S.C. § 1028 Penalty-Enhancing Provisions under

§ 1028(b) .........................................................464

18 U.S.C. § 1028 Special Verdict Form..........................467

18 U.S.C. § 1028 Definitions .....................................469

18 U.S.C. § 1028 Definition of “Lawful Authority”.............470

18 U.S.C. § 1028 Definition of “Interstate or Foreign

Commerce” ......................................................472

18 U.S.C. § 1028(a) Offenses and § 1028(b) Penalties .........473

18 U.S.C. § 1028(a)(1) Fraudulent Production of an

Identification Document, Authentication Feature, or False

Identification Document—Elements ..........................475

18 U.S.C. § 1028(a)(2) Fraudulent Transfer of an Identification

Document, Authentication Feature, or False Identification

Document—Elements ..........................................478

18 U.S.C. § 1028(a)(3) Fraudulent Possession of Five or more

Identification Documents, Authentication Features, or False

Identification Documents—Elements .........................481

18 U.S.C. § 1028(a)(4) Possession of an Identification

Document, Authentication Feature, or False Identification

Document with Intent to Defraud the United

States—Elements ...............................................484

18 U.S.C. § 1028(a)(5) Fraudulent Production, Transfer, or

Possession of a Document—Making Implement or

Authentication Feature—Elements...........................486

18 U.S.C. § 1028(a)(6) Possession of a Stolen Identification

Document or Authentication Feature—Elements ...........489

18 U.S.C. § 1028(a)(7) Fraudulent Transfer, Possession, or Use

of a Means of Identification—Elements ......................491

18 U.S.C. § 1028(a)(8) Trafficking in False or Actual

Authentication Features—Elements..........................494

xvi

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(1) Definition of “Authentication

Feature”..........................................................497

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(2) Definition of “Document-Making

Implement” ......................................................498

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(3) Definition of “Identification

Document” .......................................................499

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(4) Definition of “False Identification

Document” .......................................................500

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(5) Definition of “False Authentication

Feature”..........................................................501

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(6) Definition of “Issuing Authority” ......502

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(7) Definition of “Means of

Identification” ...................................................503

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(8) Definition of “Personal Identification

Card” .............................................................505

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(9) Definition of “Produce” .................506

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(10) Definition of “Transfer” ...............507

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(11) Definition of “State” ...................508

18 U.S.C. § 1028(d)(12) Definition of “Traffic”..................509

18 U.S.C. § 1028A Definition of “In Relation to”...............510

18 U.S.C. § 1028A(a)(1) Aggravated Identity

Theft—Elements ................................................511

18 U.S.C. § 1029 Access Device Fraud—Definitions...........513

18 U.S.C. § 1029 Definition of “Telecommunications

Instrument” .....................................................514

18 U.S.C. § 1029 Definition of “Hardware” .....................515

18 U.S.C. § 1029 Definition of “Software” ......................516

18 U.S.C. § 1029 Definition of “Interstate or Foreign

Commerce” ......................................................517

18 U.S.C. § 1029(a)(1) Production, Use or Trafficking in

Counterfeit Access Devices—Elements .......................518

18 U.S.C. § 1029(a)(2) Trafficking or Use of Unauthorized

Access Devices—Elements .....................................520

18 U.S.C. § 1029(a)(3) Possession of Multiple Unauthorized or

Counterfeit Access Devices—Elements .......................522

18 U.S.C. § 1029(a)(4) Production, Trafficking and Possession of

Device-Making Equipment—Elements .......................524

18 U.S.C. § 1029(a)(5) Fraudulent Transactions with Another’s

Access Device—Elements ......................................526

18 U.S.C. § 1029(a)(6) Solicitation to Sell Access Device or

Information Regarding an Access Device—Elements .......528

18 U.S.C. § 1029(a)(7) Use, Production, Trafficking or

Possession of Modified Telecommunication

Instrument—Elements .........................................530

18 U.S.C. § 1029(a)(8) Use, Production, Trafficking or

Possession of a Scanning Receiver—Elements ..............532

TABLE OF CONTENTS

xvii

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 1029(a)(9) Use, Production, Trafficking or

Possession of Hardware or Software Configured to Obtain

Telecommunication Services—Elements .....................534

18 U.S.C. § 1029(a)(10) Fraudulent Presentation of Evidence of

Credit Card Transaction to Claim Unauthorized

Payment—Elements............................................536

18 U.S.C. §§ 1029(b)(1) & (b)(2) Attempt and

Conspiracy—Elements .........................................538

18 U.S.C. § 1029(e)(1) Definition of “Access Device”...........539

18 U.S.C. § 1029(e)(2) Definition of “Counterfeit Access

Device” ...........................................................540

18 U.S.C. § 1029(e)(3) Definition of “Unauthorized Access

Device” ...........................................................541

18 U.S.C. § 1029(e)(4) Definition of “Produce” .................542

18 U.S.C. § 1029(e)(5) Definition of “Traffic” or “Trafficking”.543

18 U.S.C. § 1029(e)(6) Definition of “Device-Making

Equipment”......................................................544

18 U.S.C. § 1029(e)(7) Definition of “Credit Card System

Member” .........................................................545

18 U.S.C. § 1029(e)(8) Definition of “Scanning Receiver” .....546

18 U.S.C. § 1029(e)(9) Definition of “Telecommunications

Service” ..........................................................547

18 U.S.C. § 1029(e)(11) Definition of “Telecommunication

Identifying Information” .......................................548

18 U.S.C. § 1030 Computer Fraud and Related

Activity—Definitions ...........................................549

18 U.S.C. § 1030 Definition of “Government Entity” ..........550

18 U.S.C. § 1030 Definition of “Password”......................551

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(1) Obtaining Information from Computer

Injurious to the United States—Elements ...................552

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(2)(A), (B) & (C) Obtaining Financial

Information by Unauthorized Access of a

Computer—Elements...........................................554

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(3) Accessing a Non-Public Government

Computer—Elements...........................................557

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(4) Computer Fraud Use by or for Financial

Institution or Government—Elements .......................558

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(5)(A) Transmission of Program to

Intentionally Cause Damage to a Computer—Elements . . .560

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(5)(B) Recklessly Causing Damage by

Accessing a Protected Computer—Elements ................564

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(5)(C) Causing Damage and Loss by

Accessing a Protected Computer—Elements ................567

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(6) Trafficking in Passwords—Elements. .568

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(7)(A) Extortion by Threatening to Damage

a Protected Computer—Elements.............................570

xviii

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(7)(B) Extortion by Threatening to Obtain

Information from a Protected Computer—Elements........571

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(7)(C) Extortion by Demanding Money in

Relation to a Protected Computer—Elements ...............573

18 U.S.C. § 1030(a)(7)(C) Definition of “In Relation To”.......575

18 U.S.C. § 1030(b) Attempt and Conspiracy—Elements .....576

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(1) Definition of “Computer” ...............577

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(2) Definition of “Protected Computer” ...578

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(3) Definition of “State”.....................579

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(4) Definition of “Financial Institution” . .580

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(5) Definition of “Financial Record” .......581

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(6) Definition of “Exceeds Authorized

Access” ...........................................................582

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(7) Definition of “Department of the United

States” ...........................................................583

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(8) Definition of “Damage” .................584

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(10) Definition of “Conviction” .............585

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(11) Definition of “Loss” ....................586

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(12) Definition of “Person” .................587

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(13) Definition of “Federal Election” ......588

18 U.S.C. § 1030(e)(14) Definition of “Voting System”.........589

18 U.S.C. § 1035 False Statements Related to Health Care

Matters: Falsification and Concealment—Elements ........591

18 U.S.C. § 1035 False Statements Related to Health Care

Matters: False Statement—Elements ........................593

18 U.S.C. § 1035(a)(1) & (2) Definition of “Health Care Benefit

Program”.........................................................595

18 U.S.C. § 1035(a)(1) & (2) Definition of “Material” ..........596

18 U.S.C. § 1035(a)(1) & (2) Definition of “Willfully” ..........597

18 U.S.C. § 1111 First Degree Murder—Elements.............598

18 U.S.C. § 1111 Definition of “Malice Aforethought” .........601

18 U.S.C. § 1111 Definition of “Premeditation”.................602

18 U.S.C. § 1111 Second Degree Murder—Elements ..........603

18 U.S.C. §§ 1111 & 1112 Jurisdiction ..........................605

18 U.S.C. §§ 1111 & 1112 Conduct Caused Death .............606

18 U.S.C. § 1112 Definitions......................................607

18 U.S.C. § 1112 Definitions of Manslaughter .................609

18 U.S.C. § 1112 Voluntary Manslaughter—Elements ........610

18 U.S.C. § 1112 Definition of “Heat of Passion”...............611

18 U.S.C. § 1112 Involuntary Manslaughter—Elements ......612

18 U.S.C. § 1201(a)(1) Kidnapping ..............................614

18 U.S.C. § 1201(a)(1) Kidnapping—Definition of Interstate or

Foreign Commerce..............................................616

18 U.S.C. § 1201(a)(1) Kidnapping—Definition of Inveigle or

Decoy.............................................................617

TABLE OF CONTENTS

xix

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341 & 1343 Mail/Wire/Carrier

Fraud—Elements ...............................................618

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341 & 1343 Use of Mails/Interstate Carrier/

Interstate Communication Facility ...........................621

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341 & 1343 Success Not Required ..............623

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341 & 1343 Definition of “Scheme to

Defraud” .........................................................624

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341 & 1343 Proof of Scheme.....................627

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341 & 1343 Definition of “Material” ............629

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341 & 1343 Definition of “Intent to Defraud”..631

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341, 1343 & 1346 Types of Mail/Wire/Carrier

Fraud.............................................................632

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341, 1343 & 1346 Definition of “Honest

Services” .........................................................633

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341, 1343 & 1346 Receiving a Bribe or

Kickback .........................................................635

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341, 1343 & 1346 Offering a Bribe or

Kickback .........................................................639

18 U.S.C. §§ 1341, 1343 & 1346 Intent to Influence...........640

18 U.S.C. § 1343 Wire Communication .........................641

18 U.S.C. § 1344(1) Scheme to Defraud a Financial

Institution—Elements..........................................642

18 U.S.C. § 1344(1) Definition of “Scheme”.....................644

18 U.S.C. § 1344(2) Obtaining Bank Property by False or

Fraudulent Pretenses—Elements.............................646

18 U.S.C. § 1344(2) Definition of Scheme.......................648

18 U.S.C. § 1347(a) Definition of “Health Care Benefit

Program”.........................................................651

18 U.S.C. § 1347(a)(1) Health Care Fraud—Elements ........652

18 U.S.C. § 1347(a)(1) Definition of “Scheme”..................656

18 U.S.C. § 1347(a)(2) Obtaining Property From a Health Care

Benefit Program by False or Fraudulent Pretenses—

Elements.........................................................658

18 U.S.C. § 1347(a)(2) Definition of Scheme....................662

18 U.S.C. § 1461 Mailing Obscene Material—Elements ......664

18 U.S.C. § 1462 Bringing Obscene Material into the United

States—Elements ...............................................666

18 U.S.C. § 1462 Taking or Receiving Obscene

Material—Elements ............................................667

18 U.S.C. § 1462 Importing or Transporting Obscene

Material—Elements ............................................669

18 U.S.C. § 1465 Production with Intent to Transport/

Distribute/Transmit Obscene Material for Sale or

Distribution—Elements ........................................671

18 U.S.C. § 1465 Transportation of Obscene Material for Sale

or Distribution—Elements.....................................673

xx

Instruction Page

Definition of Interstate or Foreign Commerce .................675

18 U.S.C. § 1466 Engaging in Business of Producing/Selling

Obscene Matter—Elements....................................676

18 U.S.C. § 1466 Engaging in Business of Selling/Transferring

Obscene Matter—Elements....................................678

18 U.S.C. § 1466 Engaging in Business of Receiving/Possessing

Obscene Matter—Elements....................................680

18 U.S.C. § 1466(b) Definition of “Engaged in the Business”.682

18 U.S.C. § 1466A(a)(1) Producing/Distributing/Receiving/

Possessing with Intent to Distribute Obscene Visual

Representations of Sexual Abuse of Children—Elements . .683

18 U.S.C. § 1466A(a)(2) Producing/Distributing/Receiving/

Possessing with Intent to Distribute Obscene Visual

Representations of Sexual Abuse of Children—Elements . .685

18 U.S.C. § 1466A(b)(1) Possession of Obscene Visual

Representations of Sexual Abuse of Children—Elements . .687

18 U.S.C. § 1466A(b)(2) Possession of Obscene Visual

Representations of Sexual Abuse of Children—Elements . .689

18 U.S.C. § 1466A(f)(1) Definition of “Visual Depiction” ......691

18 U.S.C. § 1466A(f)(3) Definition of “Graphic” ................692

18 U.S.C. § 1470 Transfer of Obscene Material to a

Minor—Elements ...............................................693

18 U.S.C. § 1470 Definition of “Obscene” .......................695

18 U.S.C. § 1503 Obstruction of Justice

Generally—Elements...........................................698

18 U.S.C. § 1503 Obstruction of Justice—Clause 2—Injuring

Jurors or Their Property—Elements .........................700

18 U.S.C. § 1503 Obstruction of Justice—Clause 3—Injuring

Court Officials—Elements .....................................701

18 U.S.C. § 1503 Definition of “Endeavor”......................702

18 U.S.C. § 1503 Influencing Court Officer—Elements .......704

18 U.S.C. § 1503 Influencing Juror—Elements ................706

18 U.S.C. § 1503 Influencing Witness—Elements .............708

Special Verdict Instructions on § 1503 Offenses Alleged to Have

Involved Physical Force or the Threat of Physical Force .710

18 U.S.C. § 1512 Definition of “Corruptly” .....................712

18 U.S.C. §§ 1512 & 1515(a)(1) Definition of Official

Proceeding .......................................................713

18 U.S.C. §§ 1512 & 1515(a)(3) Definition of “Misleading

Conduct” .........................................................715

18 U.S.C. § 1512(b)(1) Witness Tampering—Influencing or

Preventing Testimony—Elements.............................716

18 U.S.C. § 1512(b)(2)(A) Witness Tampering—Withholding

Evidence—Elements............................................717

18 U.S.C. § 1512(b)(2)(B) Witness Tampering—Altering or

Destroying Evidence—Elements ..............................718

TABLE OF CONTENTS

xxi

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 1512(b)(2)(C) Witness Tampering—Evading Legal

Process—Elements .............................................719

18 U.S.C. § 1512(b)(2)(D) Witness Tampering—Absence from

Legal Proceeding—Elements ..................................721

18 U.S.C. § 1512(b)(3) Witness Tampering—Hinder, Delay or

Prevent Communication Relating to Commission of

Offense—Elements .............................................722

18 U.S.C. § 1512(c)(1) Destroy, Alter or Conceal Document or

Object—Elements...............................................724

18 U.S.C. § 1512(c)(2) Otherwise Obstruct Official

Proceeding—Elements .........................................726

18 U.S.C. § 1512(e) Affirmative Defense ........................727

18 U.S.C. §§ 1512 & 1515(a)(4) Definition of “Law Enforcement

Officer” ...........................................................728

18 U.S.C. § 1519 Obstruction of Justice—Destruction,

Alteration, or Falsification of Records in Federal

Investigations and Bankruptcy—Elements ..................729

18 U.S.C. § 1543 Forgery of Passport—Elements..............731

18 U.S.C. § 1543 False Use of Passport—Elements ...........732

18 U.S.C. § 1544 Misuse of a Passport—Elements ............734

18 U.S.C. § 1544 Furnishing a False Passport—Elements . . .736

18 U.S.C. § 1546(a) Fraudulent Immigration

Document—Elements ..........................................738

18 U.S.C. § 1546(a) Making a False Statement on Immigration

Document—Elements ..........................................740

18 U.S.C. § 1546(a) Presentation of False Statement on

Immigration Document—Elements ...........................742

18 U.S.C. § 1546(a) Definition of Material......................743

18 U.S.C. § 1591 Sex Trafficking of a Minor—Elements ......744

18 U.S.C. § 1591 Benefitting from Sex Trafficking of a

Minor—Elements ...............................................746

18 U.S.C. § 1591(a)(1) Sex Trafficking of a Minor or by Force,

Fraud, or Coercion—Elements ................................748

18 U.S.C. § 1591(e)(1) Definition of “Abuse or Threatened

Abuse of Law or Legal Process”...............................752

18 U.S.C. § 1591(e)(2) Definition of “Coercion”.................753

18 U.S.C. § 1591(e)(3) Definition of “Commercial Sex Act” .. .754

18 U.S.C. § 1591(e)(4) Definition of “Serious Harm”...........755

18 U.S.C. § 1591(e)(5) Definition of “Venture”..................756

18 U.S.C. § 1623 False Declarations Before Grand Jury or

Court—Elements................................................757

18 U.S.C. § 1623 Definition of “Materiality”....................759

18 U.S.C. § 1623 Records or Documents ........................760

18 U.S.C. § 1623 Sequence of Questions ........................761

18 U.S.C. § 1623 Inconsistent Statements......................762

18 U.S.C. § 1623 Recantation ....................................763

xxii

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 1701 Obstruction of Mails ..........................765

18 U.S.C. § 1708 Theft of Mail from Authorized

Depository—Elements..........................................766

18 U.S.C. § 1708 Mail Theft on or Next to a

Depository—Elements..........................................769

18 U.S.C. § 1708 Buying, Receiving, Concealing, or Unlawfully

Possessing Stolen Mail—Elements ...........................771

18 U.S.C. § 1708 Removing Contents of/Secreting/ Embezzling/

Destroying Mail.................................................773

18 U.S.C. § 1709 Theft of Mail by Officer or

Employee—Elements ...........................................774

18 U.S.C. § 1831 Economic Espionage (Including Federal

Nexus and Knowledge).........................................777

18 U.S.C. § 1832 Theft of Trade Secrets (Including Federal

Nexus and Knowledge).........................................779

18 U.S.C. § 1951 Extortion—Non-Robbery—Elements ........782

18 U.S.C. § 1951 Attempted Extortion—Elements ............784

18 U.S.C. § 1951 Extortion—Robbery—Elements..............785

18 U.S.C. § 1951 Definition of “Robbery” .......................787

18 U.S.C. § 1951 Definition of “Color of Official Right” .......788

18 U.S.C. § 1951 Definition of “Extortion”......................790

18 U.S.C. § 1951 Definition of “Property”.......................791

18 U.S.C. § 1951 Definition of “Interstate Commerce” ........792

18 U.S.C. § 1952 Interstate and Foreign Travel or

Transportation in Aid of Racketeering

Enterprises—Elements.........................................794

18 U.S.C. § 1952 Definition of “Interstate Commerce” ........797

18 U.S.C. § 1952 Definition of “Unlawful Activity”—Business

Enterprise .......................................................798

18 U.S.C. § 1952 Definition of Unlawful Business Activity—

Controlled Substances..........................................799

18 U.S.C. § 1956 Definition of “Proceeds”.......................800

18 U.S.C. § 1956 Definition of Knowledge Requirement ......802

18 U.S.C. § 1956 Definition of “Transaction” ...................803

18 U.S.C. § 1956 Definitions .....................................804

18 U.S.C. § 1956 Definition of “Conceal or Disguise”..........806

18 U.S.C. § 1956(a)(1)(A)(i) Money Laundering—Promoting

Unlawful Activity—Elements..................................807

18 U.S.C. § 1956(a)(1)(A)(ii) Money Laundering—Tax

Violations—Elements...........................................809

18 U.S.C. § 1956(a)(1)(B)(i) Money Laundering—Concealing or

Disguising—Elements..........................................811

18 U.S.C. § 1956(a)(1)(B)(ii) Money Laundering—Avoiding

Reporting—Elements...........................................813

18 U.S.C. § 1956(a)(2)(A) Money Laundering—International

Promotion—Elements ..........................................815

TABLE OF CONTENTS

xxiii

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 1956(a)(2)(B)(i) Money Laundering—International

Concealing or Disguising—Elements .........................817

18 U.S.C. § 1957 Unlawful Monetary Transactions in

Criminally Derived Property—Elements.....................819

18 U.S.C. § 1957 Definitions .....................................821

18 U.S.C. § 1959(a) Violent Crimes in Aid of Racketeering

Activity...........................................................823

18 U.S.C. § 1961(4) Enterprise—Legal Entity .................826

18 U.S.C. § 1961(4) Enterprise—Association in Fact..........827

18 U.S.C. § 1962 Definition of “Interstate Commerce” ........828

18 U.S.C. § 1962(c) Substantive Racketeering—Elements. . . .829

18 U.S.C. § 1962(c) Pattern Requirement—Substantive

Racketeering ....................................................830

18 U.S.C. § 1962(c) Subparts of Racketeering Acts ............831

18 U.S.C. § 1962(d) Racketeering Conspiracy—Elements . ...832

18 U.S.C. § 1962(d) Pattern Requirement—Racketeering

Conspiracy.......................................................834

18 U.S.C. § 1962(c) & (d) Definition of “Conduct or participate

in the conduct of” ...............................................836

18 U.S.C. § 1962(c) & (d) Definition of “Associate” ............837

18 U.S.C. § 1963(a)(1) Forfeiture—Elements...................838

18 U.S.C. § 1963(a)(1) Definition of “Interest” .................840

18 U.S.C. § 1963(a)(2) Forfeiture—Elements...................841

18 U.S.C. § 1963(a)(3) Forfeiture—Elements...................843

18 U.S.C. § 1963(a)(3) Definition of “Proceeds” ................845

18 U.S.C. § 1963(b) Definition of “Property”....................846

Forfeiture Verdict Form...........................................847

18 U.S.C. § 2113(a) Bank Robbery—Elements .................848

18 U.S.C. § 2113(a) Definition of “Intimidation” ...............850

18 U.S.C. § 2113(a) Entering to Commit Bank Robbery or

Another Felony—Elements ....................................851

18 U.S.C. § 2113(b) Bank Theft—Elements ....................853

18 U.S.C. § 2113(b) Definition of “Steal” ........................855

18 U.S.C. § 2113(c) Possession of Stolen Bank Money or

Property—Elements ............................................856

18 U.S.C. § 2113(d) Armed Bank Robbery—Elements ........859

18 U.S.C. § 2113(d) Definition of “Assault” .....................861

18 U.S.C. § 2113(d) Definition of “Put in Jeopardy the Life of” a

Person............................................................862

18 U.S.C. § 2113(d) Definition of “Dangerous Weapon or

Device” ...........................................................863

18 U.S.C. § 2113(e) Kidnapping or Murder During a Bank

Robbery—Elements.............................................864

18 U.S.C. § 2114(a) Assault with Intent to Rob Mail Matter,

Money, or Other Property of the United

States—Elements ...............................................866

xxiv

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 2114(a) Robbery or Attempted Robbery of Mail

Matter, Money, or Other Property of the United

States—Elements ...............................................868

18 U.S.C. § 2114(a) Wounding or Putting a Life in Jeopardy

During a Robbery or Attempted Robbery of Mail Matter,

Money, or Other Property of the United

States—Elements ...............................................870

18 U.S.C. § 2114(b) Receipt, Possession, Concealment, or

Disposal of Stolen Mail Matter, Money, or Other Property of

the United States—Elements .................................872

18 U.S.C. § 2241(a) Aggravated Sexual Abuse—Elements....873

18 U.S.C. § 2241(b)(1) Aggravated Sexual Abuse—Rendering

Victim Unconscious—Elements ...............................875

18 U.S.C. § 2241(b)(2) Aggravated Sexual Abuse—

Administration of Drug, Intoxicant or Other

Substance—Elements ..........................................876

18 U.S.C. § 2241(c) Aggravated Sexual Abuse of

Child—Elements ................................................878

18 U.S.C. § 2241(c) Aggravated Sexual Abuse of a Minor

Twelve to Sixteen—Elements..................................880

18 U.S.C. § 2241(c) Aggravated Sexual Abuse—Rendering

Victim Unconscious, Minor Twelve to Sixteen—Elements .882

18 U.S.C. § 2241(c) Aggravated Sexual Abuse—Administration

of Drug, Intoxicant or Other Substance, Minor Twelve to

Sixteen—Elements .............................................884

18 U.S.C. § 2243(a) Sexual Abuse of Minor—Elements .......886

18 U.S.C. §§ 2243(a), 2423(b) & 2241(c) Crossing State Line

with Intent to Engage in Sexual Act with

Minor—Elements ...............................................887

18 U.S.C. § 2243(b) Sexual Abuse of Person in Official

Detention—Elements...........................................889

18 U.S.C. § 2243(b) Definition of “Official Detention” .........890

18 U.S.C. § 2243(c)(1) Defense of Reasonable Belief of Minor’s

Age ...............................................................891

18 U.S.C. §§ 2242 & 2244(a) Abusive Sexual

Contact—Elements .............................................892

18 U.S.C. §§ 2244(a)(2) Abusive Sexual Contact—Incapacitated

Victim—Elements...............................................893

18 U.S.C. § 2244(b) Abusive Sexual Contact Without

Permission—Elements .........................................894

18 U.S.C. § 2246(2) Definition of “Sexual Act” .................895

18 U.S.C. § 2246(3) Definition of “Sexual Contact” ............896

18 U.S.C. § 2250(a) Failure to Register/Update as Sex

Offender—Elements ............................................897

18 U.S.C. § 2251(a) Sexual Exploitation of

Child—Elements ................................................899

TABLE OF CONTENTS

xxv

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 2251(b) Sexual Exploitation of Child—Permitting

or Assisting by Parent or Guardian—Elements .............902

18 U.S.C. § 2251(c) Sexual Exploitation of Child—Conduct

Outside of the United States—Elements.....................904

18 U.S.C. § 2251(d) Publishing of Child

Pornography—Elements .......................................906

18 U.S.C. § 2251A(a) Selling of Children—Elements..........908

18 U.S.C. § 2251A(b) Purchasing or Obtaining Children .....911

18 U.S.C. § 2252A(a)(1) Mailing, Transporting or Shipping

Material Containing Child Pornography—Elements .......914

18 U.S.C. § 2252A(a)(2)(A) Receipt or Distribution of Child

Pornography—Elements .......................................916

18 U.S.C. § 2252A(a)(2)(B) Receipt or Distribution of Material

Containing Child Pornography—Elements ..................918

18 U.S.C. § 2252A(a)(3)(A) Reproduction of Child Pornography

for Distribution—Elements ....................................920

18 U.S.C. § 2252A(a)(4)(A) Sale or Possession with Intent to

Sell of Child Pornography in U.S. Territory—Elements. . . .922

18 U.S.C. § 2252A(a)(4)(B) Sale or Possession with Intent to

Sell of Child Pornography in Interstate or Foreign

Commerce—Elements ..........................................924

18 U.S.C. § 2252A(a)(5)(A) Possession of or Access with Intent

to View Child Pornography in U.S. Territory—Elements ..926

18 U.S.C. § 2252A(a)(5)(B) Possession of or Access with Intent

to View Child Pornography in Interstate

Commerce—Elements ..........................................928

18 U.S.C. §§ 2252A(a)(6)(A), (B) & (C) Providing Child

Pornography to a Minor—Elements ..........................930

18 U.S.C. § 2252A(a)(7) Production with Intent to Distribute

and Distribution of Adapted Child

Pornography—Elements .......................................932

18 U.S.C. § 2252A(c) Affirmative Defense to Charges under 18

U.S.C. §§ 2252A(a)(1), (a)(2), (a)(3)(A), (a)(4) or (a)(5) ......934

18 U.S.C. § 2252A(d) Affirmative Defense to Charge under 18

U.S.C. § 2252A(a)(5) ............................................936

18 U.S.C. § 2256(1) Definition of “Minor”.......................937

18 U.S.C. § 2256(2)(A) Definition of “Sexually Explicit

Conduct” .........................................................938

18 U.S.C. § 2256(3) Definition of “Producing” ..................939

18 U.S.C. § 2256(6) Definition of “Computer” ..................940

18 U.S.C. § 2256(7) Definition of “Custody or Control” .......941

18 U.S.C. § 2256(8) Definition of “Child Pornography”........942

18 U.S.C. § 2256(9) Definition of “Identifiable Minor”.........943

18 U.S.C. § 2256(11) Definition of “Indistinguishable” ........944

18 U.S.C. § 2260(a) Production of Sexually Explicit Depictions

of a Minor—Importation—Elements..........................945

xxvi

Instruction Page

18 U.S.C. § 2260(b) Use of a Visual

Depiction—Importation—Elements...........................947

18 U.S.C. § 2312 Transportation of Stolen

Vehicle—Elements ..............................................949

18 U.S.C. § 2312 Definition of “Stolen” .........................951

18 U.S.C. § 2313 Sale or Receipt of Stolen

Vehicles—Elements.............................................953

18 U.S.C. § 2314 Transportation of Stolen or Converted Goods

or Goods Taken by Fraud—Elements ........................955

18 U.S.C. § 2314 Interstate Travel to Execute or Conceal

Fraud—Elements ...............................................957

18 U.S.C. § 2314 Interstate Transportation of Falsely Made,

Forged, Altered or Counterfeited Securities or Tax

Stamps—Elements .............................................959

18 U.S.C. § 2314 Interstate Transportation of a Traveler’s

Check Bearing a Forged Countersignature—Elements.....961

18 U.S.C. § 2314 Interstate Transportation of Tools Used in

Making, Forging, Altering, or Counterfeiting Any Security or

Tax Stamps—Elements ........................................963

18 U.S.C. § 2315 Receipt of Stolen Property—Elements ......965

18 U.S.C. § 2315 Receipt of Counterfeit Securities or Tax

Stamps—Elements .............................................967

18 U.S.C. § 2315 Definition of Interstate or Foreign

Commerce .......................................................969

18 U.S.C. § 2325 Definition of “Telemarketing” Applicable to

Enhanced Penalties under 18 U.S.C. § 2326 ................970

18 U.S.C. § 2339A Definition of “Material Support or

Resources” .......................................................971

18 U.S.C. § 2339A Providing Material Support to

Terrorists—Elements ...........................................972

18 U.S.C. § 2339B Providing Material Support or Resources to

Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations—Elements . ..975

18 U.S.C. § 2421 Transportation for Prostitution/Sexual

Activity—Elements .............................................981

18 U.S.C. § 2422(a) Enticement—Elements ....................983

18 U.S.C. § 2422(b) Enticement of a Minor—Elements .......985

18 U.S.C. § 2423(a) Transportation of Minors with Intent to

Engage in Criminal Sexual Activity—Elements.............987

18 U.S.C. § 2423(b) Interstate Travel with Intent to Engage in

a Sexual Act with a Minor—Elements .......................989

18 U.S.C. § 2423(c) Foreign Travel with Intent to Engage in a

Sexual Act with a Minor—Elements..........................990

18 U.S.C. § 2423(f) Definition of “Illicit Sexual Conduct” .....991

18 U.S.C. § 2423(g) Defense ......................................992

18 U.S.C. § 2425 Use of Interstate Facilities to Transmit

Information About a Minor—Elements.......................993

TABLE OF CONTENTS

xxvii

Instruction Page

21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1) Distribution of a Controlled

Substance—Elements ..........................................995

21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1) Definition of “Distribution” ..............997

21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1) Possession with Intent to

Distribute—Elements ..........................................998

21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1) Definition of “Controlled Substance”..1000

21 U.S.C. §§ 841(b)(1)(A), (B) or (C) Definition of “Serious

Bodily Injury”..................................................1001

21 U.S.C. §§ 841(b)(1)(A), (B) or (C) Where Death or Serious

Bodily Injury Results—Special Verdict Form ..............1002

21 U.S.C. § 841(c)(1) Possession of Listed Chemical with Intent

to Manufacture—Elements...................................1005

21 U.S.C. § 841(c)(2) Possession/Distribution of Listed

Chemical for Use in Manufacture—Elements..............1007

21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1) & (c) Definition of “Possession” ........1009

Introductory Forfeiture Instruction ............................1010

Forfeiture Allegations Instruction..............................1012

Forfeiture Burden of Proof Instruction ........................1013

Forfeiture—Third Party Interests..............................1014

Separate Consideration—Forfeiture Allegations..............1015

Separate Consideration—Multiple Defendants ...............1016

21 U.S.C. § 843(b) Use of Communication Facility in Aid of

Narcotics Offense—Elements ................................1017

21 U.S.C. § 843(b) Definition of “Facilitate”...................1019

21 U.S.C. § 844 Simple Possession—Elements ...............1020

21 U.S.C. § 846 Attempted Distribution of Controlled

Substance—Elements .........................................1021

21 U.S.C. § 846 Attempted Possession with Intent to

Distribute—Elements .........................................1023

Drug Quantity/Special Verdict Instructions...................1025

21 U.S.C. § 848 Continuing Criminal

Enterprise—Elements ........................................1028

21 U.S.C. § 848 Continuing Criminal Enterprise—Continuing

Series of Offenses .............................................1030

21 U.S.C. § 848 Continuing Criminal Enterprise—Five or More

Persons .........................................................1031

21 U.S.C. § 848 Continuing Criminal Enterprise—Organizing,

Managing, Supervising .......................................1032

21 U.S.C. § 848 Continuing Criminal Enterprise—Substantial

Income or Resources ..........................................1033

21 U.S.C. § 853 Drug Forfeiture—Elements ..................1034

21 U.S.C. § 853(b) Definition of “Property”....................1036

21 U.S.C. § 853(d) Rebuttable Presumption ..................1037

21 U.S.C. § 856(a)(1) Maintaining Drug-Involved

Premises—Elements .........................................

.1038

xxviii

Instruction Page

21 U.S.C. § 856(a)(1) Maintaining Drug-Involved Premises—

Limiting Instruction ..........................................1040

21 U.S.C. § 856(a)(2) Maintaining Drug-Involved

Premises—Elements ..........................................1041

21 U.S.C. § 859 Distribution of Controlled Substance to Person

under 21—Elements ..........................................1043

21 U.S.C. § 951(a)(2) Definition of Customs Territory of the

United States ..................................................1045

21 U.S.C. § 952(a) Definition of “Controlled Substance” .....1046

21 U.S.C. §§ 952(a) & (b); 960(a) Importation of Controlled

Substances—Elements........................................1047

22 U.S.C. § 2778 Importing/Exporting Weapons Without a

License..........................................................1049

22 U.S.C. § 2778(c) Willfully—Definition......................1051

26 U.S.C. § 5845 Definitions of Firearm-Related Terms .....1052

26 U.S.C. § 5861(a) Failure to Pay Tax or

Register—Elements ...........................................1053

26 U.S.C. § 5861(d) Receiving or Possessing an Unregistered

Firearm—Elements ...........................................1054

26 U.S.C. § 5861(h) Receipt or Possession of a Firearm with an

Obliterated, Removed, Changed, or Altered Serial

Number—Elements ...........................................1056

26 U.S.C. § 5861(j) Transporting, Delivering or Receiving an

Unregistered Firearm—Elements ...........................1058

26 U.S.C. § 7201 Attempt to Evade or Defeat

Tax—Elements.................................................1060

26 U.S.C. § 7201 Unanimity as to Acts of Evasion ...........1062

26 U.S.C. § 7201 No Need for Tax Assessment ...............1063

26 U.S.C. §§ 7201, 7203 & 7206 Knowledge of Contents of

Return ..........................................................1064

26 U.S.C. §§ 7201, 7203 & 7206 Funds or Property from

Unlawful Sources..............................................1065

26 U.S.C. § 7203 Failure to File Tax Return—Elements . . . .1066

26 U.S.C. § 7203 When Person Is Obligated to File Return.1068

26 U.S.C. § 7203 Tax Return Must Contain Sufficient

Information ....................................................1070

26 U.S.C. § 7206 Definition of “Material” .....................1071

26 U.S.C. § 7206(1) Fraud and False

Statements—Elements .......................................1072

26 U.S.C. § 7206(2) Aiding and Abetting in Submitting False

and Fraudulent Return—Elements .........................1074

26 U.S.C. § 7206(2) Knowledge of Taxpayer Irrelevant......1076

26 U.S.C. § 7212 Corruptly Endeavoring to Obstruct or Impede

Due Administration of Internal Revenue

Laws—Elements...............................................1077

26 U.S.C. § 7212 Good Faith....................................1079

TABLE OF CONTENTS

xxix

Instruction Page

31 U.S.C. § 5324(a)(3) Structuring Financial

Transactions—Elements ......................................1080

31 U.S.C. § 5324(a)(3) Definition of Structuring Financial

Transactions ...................................................1082

42 U.S.C. § 408(a)(3) Making or Causing to Be Made a False

Statement or Representation of Material Fact for Use in

Determining a Federal Benefit—Elements .................1083

42 U.S.C. § 408(a)(7)(A) Use of a Falsely Obtained Social

Security Number—Elements.................................1085

42 U.S.C. § 408(a)(7)(A) & (B) Definition of “Intent to

Deceive” ........................................................1087

42 U.S.C. § 408(a)(7)(B) Use of a False Social Security

Number—Elements ...........................................1088

42 U.S.C. § 408(a)(7)(C) Social Security Card

Violations—Elements .........................................1090

42 U.S.C. § 408(a)(7)(C) Definition of “Counterfeit” ..........1092

42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b) Criminal Penalties for Acts Involving

Federal Health Care Programs—Illegal Remunerations. .1093

xxx

CRIMINAL INSTRUCTIONS

INTRODUCTION

To: Judges and Criminal Law Practitioners of the U.S. District

Courts of the Seventh Circuit

From: The Committee on Federal Criminal Jury Instructions of

the Seventh Circuit

The Committee on Federal Criminal Jury Instructions of the

Seventh Circuit presents the 2023 edition of the William J. Bauer

Pattern Criminal Jury Instructions of the Seventh Circuit. These

instructions are intended to be used in connection with criminal

jury trials in the District Courts of the Seventh Circuit. This edi-

tion represents a substantial review and updating of the 2020

bound volume, as well as the 2022 digital update. The changes in

and additions to this edition reflect comments from the bench and

bar, as well as a thorough review of developments in case law –

particularly, though not exclusively, coming from the Supreme

Court and the Seventh Circuit. It includes both revisions of prior

instructions and several new instructions covering issues and of-

fenses for which judges and lawyers practicing criminal law in our

Circuit have expressed a need, as well as substantial updates to

the research reflected in the Committee Comments.

These instructions and their accompanying commentary have

been approved in principle by the Judicial Council of the Seventh

Circuit. This means that, although they have not been approved

for use in any specific case, the Council has authorized their publi-

cation as an aid to judges and lawyers practicing criminal law in

the District Courts of this Circuit. See United States v. Edwards,

869 F.3d 490, 496-97 (7th Cir. 2017).

As in prior editions, the instructions are presented in three

sections. The first section is a set of pattern preliminary instruc-

tions to be used at the outset of a criminal trial. The second sec-

tion, entitled “General Instructions,” incudes instructions gener-

ally applicable to the trial process, as well as instructions

addressing common legal theories of liability (such as conspiracy

and aid and abetting) and certain defense theories (including affir-

1

mative defenses). The final (and much larger) section, entitled

“Statutory Instructions,” contains instructions related to specific

statutory provisions located in Title 18 and in other parts of the

United States Code where criminal statutes are found. This sec-

tion is organized in order of statutory cite.

In producing this edition, whether drafting new instructions

or revising existing ones, the Committee has continued to try to

use plain language intelligible to lay jurors and to reduce the use

of legalisms. This effort reflects the experience conveyed by com-

ments we received from Committee members and other criminal

practitioners and judges, as well as some academic study of the ef-

fectiveness of specific language with lay people. We have also

continued to try to use only as many words as necessary in order

to keep instructions as simple and cleanly worded as possible, al-

though there are still a few instances in which adding a clarifying

word or a defining or explanatory phrase makes an instruction

clearer. In some cases the Committee has therefore continued to

follow the advice offered in United States v. Hill, 252 F.3d 919, 923

(7th Cir. 2001), that some instructions work better when they give

the jury the reasons underlying their admonition.

It is the Committee’s intent that juries be instructed as much

as is necessary, but not more so. In producing the 2023 edition the

Committee has remained mindful of the need to avoid giving juries

instructions about issues that are unnecessary to their delibera-

tions, as well as the need to avoid making simple concepts unnec-

essarily complex. Some instructions, such as those explaining

important preliminary or structural issues or setting forth the ele-

ments of an offense, will always be necessary, and some complex

terms or concepts will require the giving of definitional instruc-

tions we have included. But we continue to note the Court’s advice

in Hill that “[u]nless it is necessary to give an instruction, it is

necessary not to give it, so that the important instructions stand

out and are remembered.” 252 F.3d at 923; see also United States

v. Blitch, 773 F.3d 837, 847 (7th Cir. 2014) (same); United States v.

McKnight, 665 F.3d 786, 794 (7th Cir. 2011) (same); cf. United

States v. McKnight, 671 F.3d 664, 665 (7th Cir. 2012) (Posner, J.,

joined by Kanne and Williams, J.J., dissenting from denial of

rehearing en banc; “[G]ratuitous instructions confuse, and should

not be given.”).

While judges should not hesitate to instruct a jury on any is-

sue it should know about to decide the case, we thus recommend

against giving instructions that are not needed for that purpose.

In particular, we advise against giving an instruction just because

INTRODUCTION

2

a judge sees no reason not to give it (or just because it is included

in this book), in order to avoid diluting the impact of necessary

instructions and potentially injecting superfluous issues into the

jury’s deliberations. As Hill pointed out, a set of pattern instruc-

tions “offers model instructions for occasions when they are ap-

propriate but does not identify those occasions.” 252 F.3d at 923;

see also Edwards, 869 F.3d at 497. Trial judges should always

have an affirmative and case-specific reason for giving any jury

instruction, whether it is a pattern instruction or otherwise.

We continue to commend the Committee Comments to the us-

ers of these instructions. They reflect a great deal of research and

drafting effort on the part of the Committee’s members, and they

continue to be a valuable source of authority and general advice

regarding when an instruction might or might not be given, as

well as on the broad state of the law on the issue the instruction

addresses. That said, the Comments are not intended to be author-

itative in and of themselves, especially as to whether an instruc-

tion should be given in any particular case. Whether an instruc-

tion is appropriate for a given case is always a case-specific

decision, and the Committee did not have any specific case solely

in mind when drafting or commenting on a pattern instruction.

Rather, the principal value of the Comments, aside from explain-

ing the views of the Committee in offering an instruction or word-

ing it in a particular way, is their citations of cases, which we hope