Overview

The Federal Reserve reports on the profitability of credit card operations of

depository institutions, as directed by section 8 of the Fair Credit and Charge

Card Disclosure Act of 1988.

1

This is the 34th report. This report analyzes

the profitability over time of credit card operations by examining the perfor-

mance of institutions that specialize in such activities. This report also

reviews trends in credit card pricing, including changes in interest rates. The

analysis in this report is based to a great extent on information from the Con-

solidated Reports of Condition and Income (Call Reports) and the Quarterly

Report of Credit Card Plans.

2

This report contains the following topics:

•

the identification of credit card banks;

•

an overview of credit card bank profitability in 2023;

•

additional background information on the credit card market, including

market structure; and

•

an analysis of trends in credit card pricing.

Identification of Credit Card Banks

Every insured bank files a Call Report each quarter with its federal supervi-

sory agency.

3

While the Call Report provides a comprehensive balance sheet

and income statement for each bank, it does not allocate all expenses or

attribute all revenues to specific product lines, such as credit card accounts.

1

See Fair Credit and Charge Card Disclosure Act, Pub. L. No. 100-583, 102 Stat. 2960 (1988).

The 2000 report covering 1999 data was not prepared as a consequence of the Federal

Reports Elimination and Sunset Act. The report was subsequently reinstated by law.

2

The data used in this report are as of December 31, 2023, and do not reflect economic and

financial conditions since then. The Federal Reserve collects the data from the Quarterly

Report of Credit Card Plans (form FR 2835a).

3

The sample of banks used for this report includes commercial banks, state savings banks,

and thrifts.

Contents

Overview 1

Identification of Credit Card

Banks

1

Credit Card Bank Profitability 2

Market Structure and Additional

Background

5

Recent Trends in Credit Card

Pricing

7

REPORT TO CONGRESS

Profitability of Credit Card

Operations of Depository

Institutions

June 2024

BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM www.federalreserve.gov

Thus, the data may be best used to assess the profitability of credit card activities by analyzing

the earnings of only those banks established primarily to issue and service credit card accounts.

These specialized, or monoline, banks are referred to here as “credit card banks.”

For purposes of this report, credit card banks are defined by two criteria: (1) More than 50 percent

of their assets are loans to individuals (consumer lending), and (2) 90 percent or more of their

consumer lending involves credit cards or related plans.

4

Given this definition, it can reasonably

be assumed that the profitability of these banks primarily reflects returns from their credit card

operations.

5

As of December 31, 2023, eight banks met the definition of a credit card bank, and, at the time,

these banks accounted for 28 percent of outstanding credit card balances on all banks’ bal-

ance sheets.

Both the number of monoline credit card banks and the share of total credit card balances held

by credit card banks have declined in recent years. In 1996, 42 credit card banks constituted

77 percent of outstanding credit card balances. However, by 2019, 10 credit card banks in our

sample accounted for less than 40 percent of credit card balances.

6

Despite the declines in the

number and aggregate size of credit card banks, the profitability of this small set of credit card

banks appears to be representative of the profitability of the credit card operations of the banking

industry. For example, during the 2014–19 period, the profitability of credit card banks was very

similar, in both levels and trends, to the profitability of the credit card industry overall, as meas-

ured by a different data set of the credit card portfolios of the largest banks, which represent

80 percent of all outstanding credit card balances reported in the Call Report.

7

Credit Card Bank Profitability

Tracking credit card profitability over time is complicated. The sample of credit card banks can

change somewhat from one year to the next because of changing bank loan portfolios and

4

The first credit card banks were chartered in the early 1980s; few were in operation before the mid-1980s. To provide a

reliable picture of the year-to-year changes in the profitability of the credit card operations of card issuers, previous

reports limited their focus to credit card banks with at least $200 million in assets. Since 2015, all credit card banks

that satisfied the two stated criteria had more than $200 million in assets.

5

One bank (Discover Bank) included in the sample did not exactly meet these criteria. This bank is a major issuer on the

Discover network, and its balance sheet is largely consistent with the credit-card-focused business model.

6

The decline in the share of credit card balances held by credit card banks has been driven in large part by reorganiza-

tions. Many of the largest banks had standalone subsidiaries for their credit card operations, separate from their main

banking operations. In recent years, some of these banks have combined all their operations into a single subsidiary

that files a single Call Report each quarter and, often, does not meet the criteria for a credit card bank.

7

The profitability of credit card banks was slightly lower than that of the credit card portfolios of the largest banks in

2020 and 2021. For a discussion of the comparison of the two data sets, see Robert Adams, Vitaly M. Bord, and

Bradley Katcher (2022), “Credit Card Profitability,” FEDS Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System, September 9), https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3100.

2 Profitability of Credit Card Operations of Depository Institutions

reorganizations. Thus, overall changes in profit rates can reflect both changes in activity and

changes in the sample composition. That said, there were no changes in the sample of included

credit card banks from 2022 to 2023.

Another difficulty that arises in assessing the

profitability of credit card activities over time

is due to changes in accounting rules. For

example, accounting rule changes imple-

mented in 2010 required banking institutions

to consolidate on their Call Reports some pre-

viously off-balance-sheet items (such as

credit-card-backed securities). To the extent

that previously off-balance-sheet assets have

a different rate of return than on-balance-

sheet assets, profitability measures based on

Call Report data in 2010 and after are not

necessarily comparable with those

before 2010.

Similarly, large credit card banks that file with

the Securities and Exchange Commission

began using the current expected credit

losses (CECL) methodology to estimate provi-

sions for loan losses on January 1, 2020.

CECL replaced the previously used incurred

loss methodology and incorporates some

forward-looking information in estimating

expected credit losses.

8

Because of this

change in methodology, starting in 2020, loan

loss provisions are not necessarily compa-

rable with those before 2020.

In 2023, credit card banks reported net earn-

ings, before taxes and extraordinary items, of

3.33 percent of average quarterly assets,

down from 4.70 percent in 2022 (table 1).

9

8

For more information on CECL, see https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/topics/faq-new-accounting-

standards-on-financial-instruments-credit-losses.htm.

9

The 2022 estimate of the return on assets was revised from 4.71 to 4.70, reflecting revisions to the Call Report data.

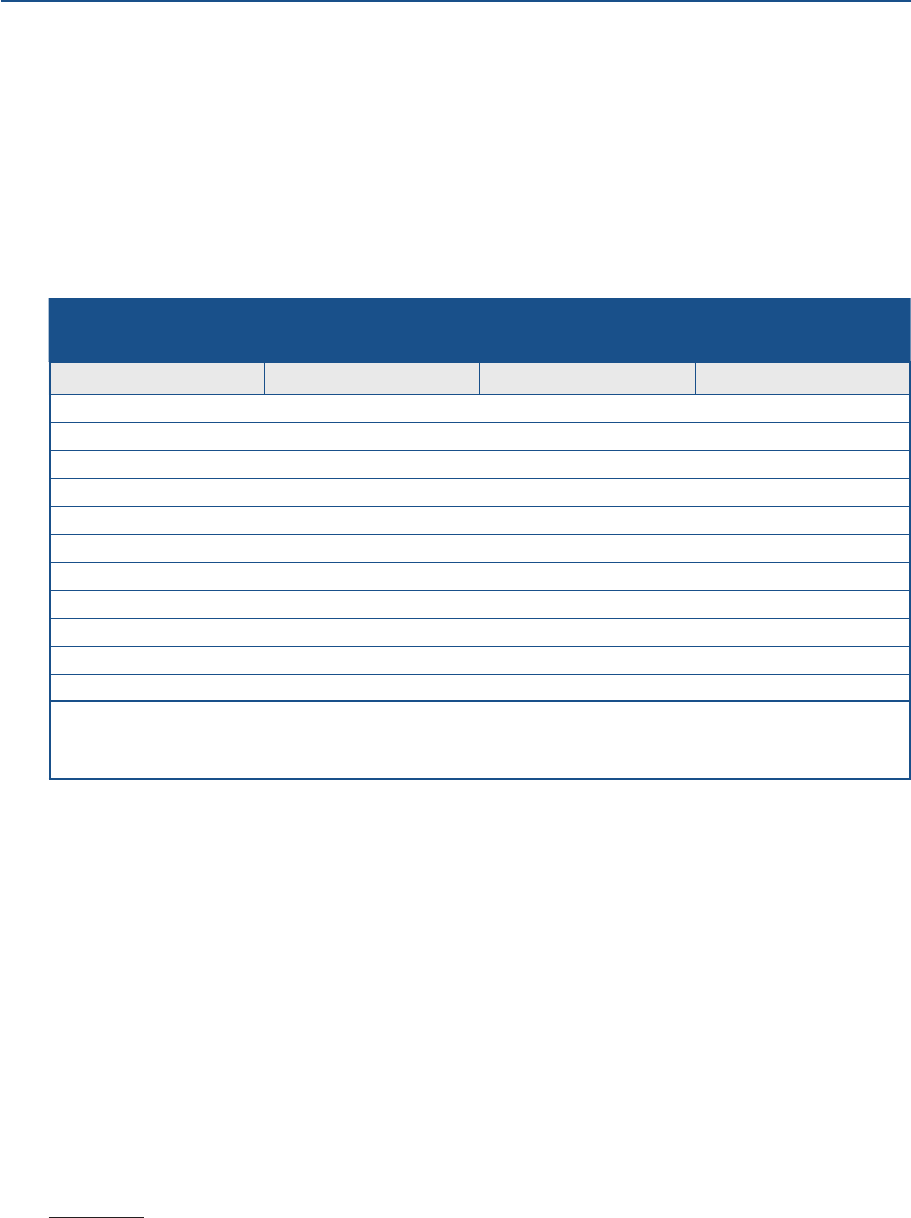

Table 1. Annualized return on assets, large

U.S. credit card banks, 2001–23

Percent

Year Return

2001 4.83

2002 6.06

2003 6.73

2004 6.30

2005 4.40

2006 7.65

2007 5.08

2008 2.60

2009 –5.33

2010 2.41

2011 5.37

2012 4.80

2013 5.20

2014 4.94

2015 4.36

2016 4.04

2017 3.37

2018 3.79

2019 4.14

2020 2.40

2021 6.93

2022 4.70

2023 3.33

Note: Credit card banks are banks with a minimum 50 percent

of assets in consumer lending and 90 percent of consumer

lending in the form of revolving credit. Profitability of credit card

banks is measured as net pretax income as a percentage of

average quarterly assets.

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Con-

solidated Reports of Condition and Income (Call Reports),

https://www.ffiec.gov.

Credit Card Bank Profitability 3

The decline in profitability in 2023 mainly reflected a continued increase in provisioning for loan

losses (table 2). As discussed in the 2021 report, banks shrank their provisioning to a historically

low rate in 2021, as losses expected during the COVID-19 pandemic did not materialize. Starting

in 2022, banks began to increase their loan loss provisions, and in 2023 provisioning rose to

3.92 percent of average quarterly assets, closer to its historical average yearly rate for the

2001–19 period of 4.12 percent of assets.

Other changes in individual income and expense items did not contribute meaningfully to the

change in profitability. Net interest income at credit card banks inched up in 2023, as interest

income expanded slightly faster than interest expenses amid rising interest rates. Net noninterest

income stayed approximately flat, as a slight decrease in noninterest income was offset by a

similar decrease in noninterest expenses.

Credit card earnings have almost always been higher than returns on all bank activities, and earn-

ings patterns for 2023 were consistent with historical experience.

10

The average return on all

assets, before taxes and extraordinary items, was 1.35 percent for all banks, compared with

3.33 percent for the sample of credit card banks (as shown in table 2). Delinquency and

charge-off rates for credit card loans across all banks rose in 2023. Both delinquency and

10

This report focuses on the profitability of large credit card banks, although many other banks engage in credit card

lending without specializing in this activity. The cost structures, pricing behavior, cardholder profiles, and, consequently,

profitability of these diversified institutions may differ from that of the large, specialized card issuers considered in this

report. That said, the profitability of credit card banks was representative of the profitability of the credit card portfolios

of the large, diversified banks during the 2014–19 period. See Adams, Bord, and Katcher, “Credit Card Profitability,”

in note 7.

Table 2. Income and expenses for U.S. banks in 2022 and 2023

Percent of average quarterly assets

Credit card banks in 2023 Credit card banks in 2022 All banks in 2023

Total interest income 13.30 11.10 4.92

Total interest expenses 3.38 1.44 1.92

Net interest income 9.92 9.66 3.00

Total noninterest income 6.29 6.77 1.29

Total noninterest expenses 8.96 9.41 2.52

Net noninterest income –2.67 –2.64 –1.23

Provisions for loan losses 3.92 2.32 .37

Return 3.33 4.70 1.35

Note: Credit card banks are banks with a minimum 50 percent of assets in consumer lending and 90 percent of consumer lending in the form

of revolving credit.

Source:

Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, Consolidated Reports of Condition and Income (Call Reports), https://www.ffiec.gov

.

4 Profitability of Credit Card Operations of Depository Institutions

charge-off rates are now the highest they have been since 2012.

11

That said, delinquency and

charge-off rates remain just below their longer-run pre-pandemic averages, excluding the Great

Recession period.

12

Market Structure and Additional Background

Bank cards are widely held and extensively used by consumers. According to the Federal

Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), 80 percent of families had at least one credit card

in 2022, the most recent year for which survey results are available.

13

Consumers use credit cards for a source of credit and as a convenient payment device. As a

source of credit, credit card users can borrow up to the credit limit on their account and revolve

the balance by paying less than the full amount due.

14

As a payment device, approximately

one-fourth of the outstanding balances reflect primarily “convenience use”—that is, balances con-

sumers intend to repay by their statement due date, within the standard interest-free grace period

offered by card issuers. In fact, consumer surveys, such as the SCF, typically find that more than

60 percent of cardholders report they nearly always repay their outstanding balance in full before

incurring interest each month.

15

That said, the 20 percent of credit card accounts that revolved a

balance on their credit cards in each of the previous 12 months account for about two-thirds of all

credit card revolving balances.

16

The general-purpose bank credit card market in the U.S. is dominated by cards issued on the

Visa and Mastercard networks, which, combined, accounted for 726.6 million cards, or about

85 percent of general-purpose credit cards, in 2023.

17

In addition, the American Express and Dis-

cover networks accounted for another 132.4 million general-purpose cards in 2023. The combined

total number of charges and cash advances using credit cards rose 8.1 percent to 60.8 billion

transactions in 2023. Last year, the dollar volume of these transactions rose 6.8 percent to more

than $5.9 trillion, after rising almost 20 percent in 2022.

11

See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2024), Statistical Release, “Charge-Off and Delinquency Rates

on Loans and Leases at Commercial Banks” (February 23), www.federalreserve.gov/releases/chargeoff.

12

Long-run averages were calculated over the 2000:Q1–2019:Q4 period, excluding the 2007:Q4–2010:Q4 period.

13

This statistic reflects access to general-purpose credit cards and does not include retail cards or charge cards.

14

Credit card borrowers must pay at least the minimum amount due each month to remain in good standing.

15

See Aditya Aladangady, Jesse Bricker, Andrew C. Chang, Sarena Goodman, Jacob Krimmel, Kevin B. Moore, Sarah Reber,

Alice Henriques Volz, and Richard A. Windle (2023), Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2019 to 2022: Evidence from

the Survey of Consumer Finances (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, October), https://

doi.org/10.17016/8799.

16

See Adams, Bord, and Katcher, “Credit Card Profitability,” in note 7.

17

Figures cited in this paragraph are from the Nilson Report. See HSN Consultants, Inc. (2024), Nilson Report, no. 1258

(Carpinteria, Calif.: The Nilson Report, February).

Market Structure and Additional Background 5

A relatively small group of card issuers holds most of the outstanding credit card balances, with

the top 10 holding 81 percent.

18

Several thousand other financial institutions offer credit cards to

consumers but hold a small share of outstanding credit card balances. In the aggregate, the Fed-

eral Reserve Statistical Release G.19, “Consumer Credit,” indicates that consumers carried

$1.3 trillion in outstanding balances on their revolving accounts as of the end of 2023, about

$102 billion (8.4 percent) higher than the level at the end of 2022.

Despite this strong growth in balances, data from consumers’ credit records indicate that aggre-

gate balances owed remained a small share of the total amount of available credit under out-

standing credit card lines as of the end of 2023.

19

Apart from a one-year decline in 2020, the

total dollar amount available (credit card account limits) has risen each year since 2010 and

approached $4.8 trillion at the end of 2023.

In soliciting new accounts and managing existing account relationships, issuers segment their

cardholder bases along several dimensions. For example, issuers offer more attractive rates to

customers who have good payment records while charging relatively high interest rates and fees

on higher-risk or late-paying cardholders. Card issuers also closely monitor payment behavior,

charge volume, and account profitability, and they adjust credit limits accordingly both to allow

increased borrowing capacity as warranted and to manage credit risk.

Various channels are used for new account acquisition and account retention.

20

The most impor-

tant channel in recent years is generally referred to as the digital channel, which includes email

solicitations, website advertisements, and social media advertisements. These solicitations could

stem directly from the bank or from third-party firms. At the end of 2023, more than half of

applied-for offers were received digitally. Branches, kiosks, and automated teller machines, or

ATMs, are other significant channels for account acquisition as banks take advantage of cross-

selling opportunities. Finally, direct mailings continue to be an important channel, with about

3.6 billion offers mailed in 2023, accounting for almost 19 percent of applied-for offers.

In recent years, several new trends related to credit card usage have emerged. First, some bor-

rowers have turned to personal loans for debt consolidation, including the refinancing of credit

card debt. Such loans are offered by traditional banks and finance companies as well as by finan-

cial technology lenders, often in partnership with banks. Second, the buy-now-pay-later (BNPL)

market has grown significantly over the past several years as an alternative payment method for

consumers at point of sale, particularly for online purchases. BNPL providers, many of which are

18

Four of the top 10 card issuers are in the sample of credit card banks used in this report. The other six issuers do not

meet the requirements for inclusion in the sample.

19

See Federal Reserve Bank of New York (2024), Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit: 2023:Q4 (New York:

FRBNY, February), https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/hhdc_2023q4.pdf.

20

Information and acquisition channels data in this paragraph are based on proprietary data from Mintel Comperemedia.

6 Profitability of Credit Card Operations of Depository Institutions

financial technology providers, allow consumers to pay for a purchase through an installment plan,

often with very low or zero interest. Additionally, several credit card lenders have recently intro-

duced services that allow their credit card borrowers to convert eligible credit card transactions

into installment plans post-transaction.

Recent Trends in Credit Card Pricing

The topic of credit card pricing and how it has changed in recent years has been a focus of public

attention and is, consequently, reviewed in this report. The analysis of the trends in credit card

pricing here focuses on credit card interest rates because they are the most important component

of the pricing of credit card services. Credit card pricing, however, involves other elements,

including annual fees, fees for cash advances and balance transfers, rebates, minimum finance

charges, over-the-limit fees, and late payment charges.

21

In addition, the length of the interest-free

grace period, if any, can have an important influence on the amount of interest consumers pay on

revolving credit card balances. It is also important to note that interest rates charged vary consid-

erably across credit card plans and borrowers, reflecting the various features of the plans and the

risk profile of the cardholders served.

Over time, pricing practices in the credit card market have changed. Today, card issuers offer a

broad range of plans with differing fees and rates depending on credit risk, consumer usage pat-

terns, and specific benefit packages. Following the economic downturn in 2009, new credit card

rules spurred changes in interest rate pricing in 2009 and 2010.

22

In most plans, an issuer estab-

lishes a rate of interest for customers of a given risk profile; if the consumer borrows and pays

within the terms of the plan, that rate applies. If the borrower fails to meet the plan requirements—

for example, the borrower pays late or goes over their credit limit—the issuer may reprice the

account to reflect the higher credit risk revealed by the new behavior. Regulations that became

effective in February 2010 limit the ability of card issuers to reprice outstanding balances for card-

holders who have not fallen more than 60 days behind on the payments on their accounts. Issuers

may, however, reprice outstanding balances if they were extended under a variable-rate plan and

21

The vast majority of credit card profitability arises from interest rates and late fees. Moreover, credit card account

holders who revolved a balance on their accounts either consistently or sporadically over the previous 12 months

account for almost all interest charges and the majority of all fees paid on credit card accounts. See Adams, Bord, and

Katcher, “Credit Card Profitability,” in note 7.

Additional assessments of the rates and fees charged by credit card issuers are provided in U.S. Government Account-

ability Office (2006), Credit Cards: Increased Complexity in Rates and Fees Heightens Need for More Effective Disclosures

to Consumers, report to the ranking minority member, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Home-

land Security and Governmental Affairs, U.S.Senate, GAO-06-929 (Washington: GAO, September), www.gao.gov/

new.items/d06929.pdf; and Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (2021), The Consumer Credit Card Market (Wash-

ington: BCFP, September), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-credit-card-market-

report_2021.pdf.

22

New rules include the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure (CARD) Act of 2009 and amendments to

Regulations Z and AA passed in 2010.

Recent Trends in Credit Card Pricing 7

the underlying index used to establish the rate of interest (such as the prime rate) changes.

23

These rules do not explicitly restrict initial pricing of new accounts.

The credit card pricing information used in this report is obtained from the Quarterly Report of

Credit Card Plans (form FR 2835a). This survey collects quarterly information from a sample of

credit card issuers on (1) the average nominal interest rate and (2) the average computed interest

rate. The former is the simple average interest rate posted across all accounts; the latter is the

average interest rate paid by only those accounts that incur finance charges. These two measures

can differ because some cardholders are convenience users who pay off their balances during the

interest-free grace period and therefore do not incur finance charges. Together, these two interest

rate series provide a measure of credit card pricing. The data are made available to the public

each quarter in the Federal Reserve Statistical Release G.19, “Consumer Credit.”

Form FR 2835a data indicate that the average credit card interest rate across all accounts

increased from 19 percent at the end of 2022 to 21.5 percent by the end of 2023. At the same

time, the yield on two-year nominal Treasury securities—a measure of the benchmark, or “risk

free,” rate—inched down in the beginning of 2023 but rose to close out the year at approximately

4.8 percent (figure 1). The average interest rate on accounts that incurred interest was reported to

be higher, increasing to 22.8 percent at the end of 2023.

23

According to the Mintel Comperemedia data, 94 percent of credit card mail offerings in 2023 were for variable-rate

cards. Other data sources on credit card accounts confirm this observation.

Figure 1. Average interest rates on credit card accounts

0

5

10

15

20

25

2-year Treasury rate

Interest rate, card accounts assessed interest

Interest rate, all card accounts

202320212019201720152013201120092007200520032001199919971995

Percent

Quarterly

Q4

Source: Federal Reserve Board, form FR 2835a, Quarterly Report of Credit Card Plans.

8 Profitability of Credit Card Operations of Depository Institutions

www.federalreserve.gov

0624