Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Research Department

Why Credit Cards Played a Surprisingly Big Role in the Great Recession

2021 Q2

7

T

welve years after the Great Reces-

sion, one of the biggest economic

disasters of the modern era, econ-

omists still debate exactly what led to its

persistent declines in employment and

output. The basic narrative is clear: The

collapse of the housing price bubble

destroyed swaths of wealth, and the

ensuing credit crunch within the nancial

system tightened borrowing constraints

on rms and households, depressing

consumption and investment across the

Why Credit Cards Played

a Surprisingly Big Role in

the Great Recession

By Lukasz Drozd

Economic Advisor and Economist

.

The views expressed in this article are not

necessarily those of the Federal Reserve.

When economists and policymakers try to understand how a credit

crunch within the financial sector aects consumers, they usually

don’t think of the credit card market. They should.

economy. But this basic narrative raises

further questions. Which was more

important, the destruction of wealth or

the tightening of borrowing constraints?

How much of the decline in output was

directly caused by these initial shocks, and

how much by the subsequent, domino-

like propagation mechanisms? What were

these propagation mechanisms? Finally,

what does the Great Recession teach us

about the macroprudential regulation of

credit markets?

Photo: ideabug/iStock

8

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Research Department

Why Credit Cards Played a Surprisingly Big Role in the Great Recession

2021 Q2

laws for the credit card industry altogether.

Recognizing an opportunity for additional

tax revenue, South Dakota and Delaware

were the rst states to raise their usury

laws’ ceilings on interest rates. Credit card

issuers did not wait long to relocate their

operations to these lender-friendly states,

and to this day their major oces can

be found in Wilmington, DE (for exam-

ple, JPMorgan Chase), or Sioux Falls, SD

(for example, Citibank). To retain their

nancial institutions, other states began

loosening their usury laws as well, and

today many states have no limit on credit

card interest rates.

Following the Marquette decision, credit

card borrowing steadily rose, notably

crowding out nonrevolving consumer

credit and gradually turning America

into a credit card debtor nation (Figure ).

What fueled this expansion—especially in

the s—was the steady spread of credit

card lending among lower-income and

riskier households. Credit card debt

per household relative to the annual me-

dian household income roughly doubled

every decade until the nancial crisis,

topping percent for a household with

The Rise of Credit Card Debt

Until the s, credit cards were a form

of store credit, limited to purchases of

goods and services from a single issuing

merchant and too inconvenient to become

a major source of credit for households.

It was the success of the rst general-

purpose charge card, issued by Diners

Club in the early s, that inspired Bank

of America to combine a credit line with

a charge card and oer BankAmericard,

the rst general-purpose credit card.

By the s, more than million such

cards were in circulation. Bank of America

began licensing its BankAmericard to

other banks that were issuing credit cards,

eventually spinning o BankAmericard as

a separate company called Visa.

But the revolution in payment technol-

oy did not spur a revolution in lending

right away. In the s and s, credit

cards were mainly used as a payment

instrument, and borrowing on credit cards

did not take o until the s. What

delayed the growth of credit card lending

was the combination of high ination and

usury laws that capped interest rates.

With a tight cap on interest rates, and with

ination driving up the cost of funds for

lenders, credit card lending struggled

to make a prot in the s. In fact, by

the end of the decade, due to a double-

digit spike in ination, many credit card

lenders found themselves on the brink

of collapse.

The credit card industry was saved

in , when the U.S. Supreme Court, in

Marquette National Bank of Minneapolis v.

First of Omaha Service Corporation, ruled

that if the interest rate cap in the state

where the bank is chartered is higher

than in the state where it oers its product

(in this case, a credit card), that bank may

charge a rate subject to the higher cap.

In other words, the court allowed a bank

to “export” its interest rate cap to other

states, which in the case of First of Omaha

meant that the company could issue

a credit card in Minnesota and charge an

interest rate in excess of Minnesota’s com-

paratively low cap of percent.

The broader implication of the Su-

preme Court ruling, however, was that, by

creating competition between states to

attract bank headquarters, it not only

relaxed usury laws for lucky issuers—such

as First of Omaha—but dismantled usury

Economists are still answering these

questions, but one of their key insights is

that severed access to credit played a big

role.

This insight has spurred renewed

interest in mapping the exact mechanisms

that drove the tightening of credit to

rms and households across dierent

markets, and in these mechanisms’ macro-

prudential ramications.

When economists and policymakers try

to understand how a credit crunch within

the nancial sector aects consumers,

they usually don’t think of the credit card

market. Historically, credit card borrowing

has been small, and credit card debt

involves a soft long-term commitment of

lenders to terms—an arrangement known

to be more stable and less prone to credit

supply disruptions than other forms

of debt—so it’s not obvious how, to the

detriment of borrowers, tightening of

credit conditions within the nancial

system could severely contract available

credit, force early debt repayments, or

unexpectedly hike interest payments on

outstanding credit card debt.

But, as I will explain, by the credit

card market had grown enough to have

a notable impact on aggregate consump-

tion demand. More importantly, by

a large fraction of credit card debt was

de facto short-term debt. In particular, by

many credit card borrowers were

reducing their interest rate payments by

moving balances from card to card to take

advantage of the then-ubiquitous zero-

promotional credit card oerings.

After Lehman Brothers collapsed in mid-

, triggering a credit crunch within

the nancial sector, the zero- oers

that had sustained the low cost of credit

card debt vanished from the market, lead-

ing to a massive and, for many borrowers,

unexpected interest rate hike on expiring

promotional debt. As I will argue, this led

such borrowers to cut their consumption

so they could repay debt early, which

contributed to the decline in consumption

demand during the Great Recession.

Policymakers should keep an eye on

promotional lending, and perhaps even

reserve a permanent spot for credit cards

in their macroprudential policy consider-

ations. The - crisis reminds us that

credit card borrowing remains fragile.

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

1984 1990 1995 2000 2007

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System U.S., G. Consumer Credit, Total Revolving

Credit Owned and Securitized, Outstanding [],

retrieved from , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis;

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/REVOLSL, September

, . U.S. and Census Bureau, Current Population

Survey, March and Annual Social and Economic

Supplements, and earlier.

FIGURE 1

Credit Card Borrowing Rose to

Prominence in the 1990s…

Credit card debt per family as a percentage

of median annual family income, 1984–2007

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Research Department

Why Credit Cards Played a Surprisingly Big Role in the Great Recession

2021 Q2

9

the progress in credit scoring technoloy.

The overhaul of the

U.S. personal bankruptcy regulations in the Bankruptcy Reform

Act of , which made discharging credit debt in court far easier,

and the overall increasing demand for debt by U.S. house-

holds were two other factors that contributed to the growth of

borrowing on credit cards on the demand side.

By the s, credit card companies were making more money

from credit card lending than from merchant or interchange

fees. (Merchant or interchange fees are the fees paid by merchants

on each transaction settled using a credit card.) By , of

billion in the credit card industry’s total revenues, interest reve-

nue (that is, revenue earned from nance charges) amounted to

billion, with lending-related penalty fees and cash advance fees

contributing another . billion. In comparison, merchant

fees contributed just billion to revenue. Even after subtracting

billion in costs and default losses, lending, though a more

costly part of the business, still came out on top in . These

numbers did not change dramatically until , and lending

maintained its prominent role.

At that point, with its trillion

in debt outstanding, credit card lending had grown big enough

to aect the entire economy.

at least one card by early .

Since much income growth over

the last several decades has occurred among the top percent

of earners, and these earners do not borrow on credit cards as

much, the median rather than the mean household income

provides a better picture of how important credit card lending

had become for the majority of households.

For low-income

households, credit cards often replaced far more expensive

options, such as “loan sharks” or payday lenders, and so the

growing availability of credit card debt has importantly contri-

buted to the “democratization of credit” in the U.S. (Figure ).

Although the Supreme Court ruling enabled the industry to

grow, it was, according to economic research, the convenience

of credit card debt and the rapid progress in information tech-

noloy that drove the unprecedented, decades-long expansion

in credit card borrowing. Information technoloy aected both

the direct costs of lending and indirect costs associated with

debt collection—a less visible but equally important pillar

that sustains unsecured lending.

By reducing lending costs that

creditors must cover to break even, technoloy increased the

aordability of credit card debt, fueled borrowing, and even

had a somewhat counterintuitive eect of increasing default risk

on a statistical dollar of outstanding credit card debt despite all

2007

2007

2007

2007

2007

2004

2002

1998

1995

1992

1989

1989 1989

1989 1989

First income quintile

Second income quintile Third income quintile

Fourth

income

quintile

Fifth

income

quintile

Shades indicate isolines of (fixed)

levels of credit card debt per family

Share of families with at least one card

Card debt per cardholding family 1989=100

27% 35%

500

400

300

200

100

0

45% 55% 65% 75% 85% 95% 100%

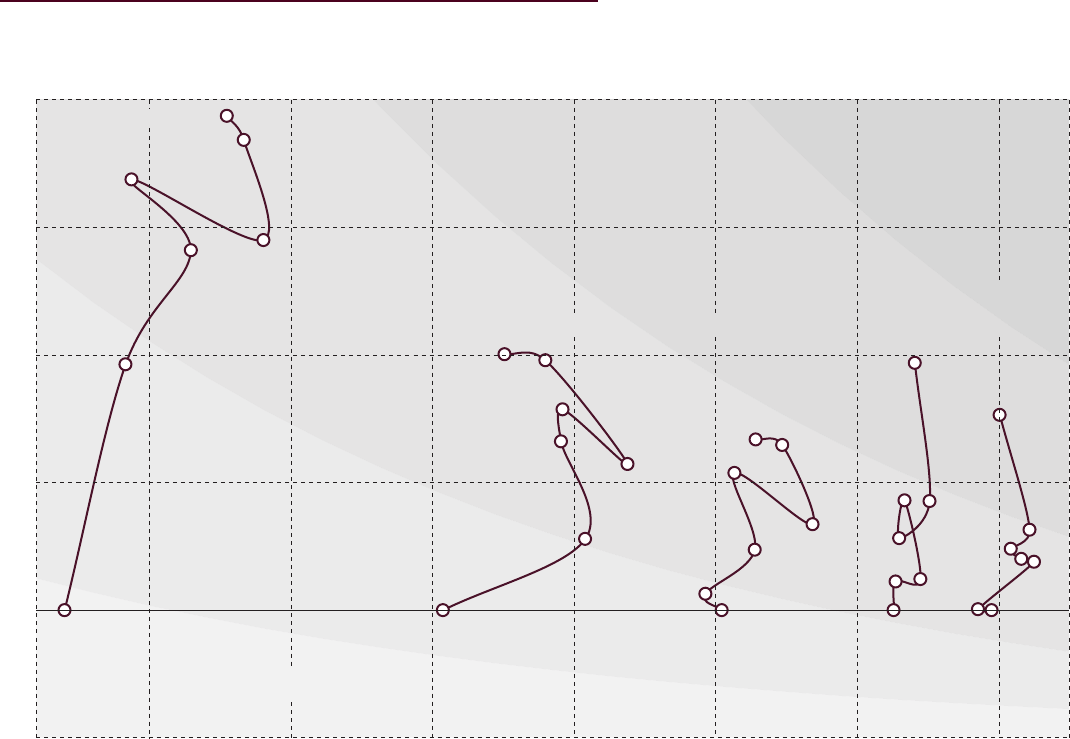

FIGURE 2

...and Contributed to the Democratization of Credit in the U.S.

Growth of credit card borrowing by income quintile, 1989–2007

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Survey of Consumer Finances ().

10

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Research Department

Why Credit Cards Played a Surprisingly Big Role in the Great Recession

2021 Q2

The Origins of “Zero”

As the credit card market became saturated in the late s

and early s, competition for customers intensied.

Balance transfers and promotional-rate oers proliferated

as the leading marketing tools.

The Marquette ruling, by

unifying regulations, set the stage for massive, nationwide

mail-marketing campaigns and permitted lenders to realize

economies of scale in marketing and processing. By the

end of the s, an ever-increasing volume of mail-in oers

dened the credit card industry, and does so to this day.

In the mid-s, Providian Financial Corporation

became the rst issuer to drop a seemingly unprotable

oer into people’s mail: a credit card with a zero on

balance transfers. This oer allowed consumers to transfer

their outstanding balance from any other credit card

account into their new Providian account (just like any

other balance-transfer oer) and pay no interest for an

introductory period. The bank could prot later only if

consumers for some reason did not repay debt after the

promotional rate expired, or if they violated the “ne

print” of the contract, triggering a penalty rate reset.

At the time, Providian had a highly protable credit

card business and was on the forefront of the industry’s

expansion to low-income customers.

The new market

looked promising but risky: Lower-income customers had

lower balances and were more likely to default, making it

dicult for credit card companies to cover the xed costs

of opening and operating their accounts. Such conditions

normally necessitate higher interest rates, but high interest

rates may also discourage borrowing, leaving lenders

exposed to default losses and bringing too little interest

income on borrowing to make a prot.

Litigation against Providian in the late s, which led

to the credit card industry’s largest Oce of the Comp-

troller of the Currency () enforcement action, oers

a unique glimpse into how the company approached the

marketing of credit cards and what led it to oer zero

. This evidence suggests that behavioral psycholoy

rather than competition was the key factor behind the

invention of “zero.”

For example, in one of internal memos to Providian’s

top executives that became public in the course of litigation,

Andrew Karr—the founder of Providian, its , and later

a strategic adviser to the company—described in this way

how the company planned to prot on subprime custo-

mers: “Making people pay for access to credit is a lucrative

business wherever it is practiced…. Is any bit of food too

small to grab when you’re starving and when there is no-

thing else in sight? The trick is charging a lot, repeatedly,

for small doses of incremental credit.”

The memo con-

rmed that the company was indeed concerned that raising

interest rates to compensate for higher lending costs might

backre, and it explained why its marketing stratey was

aimed at mitigating this issue by obscuring the true cost of

debt from borrowers—as the litigation showed.

Karr later echoed the content of this memo in a rare

interview by explaining that he suggested zero promotional

rates to Providian executives because seeing “zero” leads

borrowers to “believe what they want to believe,” which

one can infer he saw as being conducive to increased bor-

rowing by consumers even if competition ensues.

Providian paid a hefty price for its aggressive practices

in the early s, but the litigation was about the com-

pany’s deceptive practices, not the products themselves,

and zero lived on to become the hallmark of the credit

card industry in the s.

Providian’s approach may not

be representative of the industry as a whole, but recent

research shows that behavioral psycholoy provides a good

explanation for the widespread use of zero .

The Behavioral Economics of Zero APR

Zero- oers challenge standard economic theory

featuring rational consumers. When Boston Fed economist

Michal Kowalik and I studied a standard model of credit

card lending in which lenders can oer any introductory

promotional rate to (rational) borrowers, we found that,

under standard economic theory, rates should fully price

in the risk of default and the cost of funds, resulting in at

interest schedules and few introductory promotions.

Although the model can generate introductory promotion-

al oers when the default risk of a borrower is expected

to decline sharply, such occurrences are rare, and under

plausible conditions the model does not even come

close to accounting for the large volume of such oers

in the data.

The key reason is that rational consumers are best

served by prices that closely reect the true resource cost

of lending them money—which, among other items, in-

cludes the compensation to the lender for bearing the risk

that the borrower may default under some circumstances

(default risk premium).

In particular, when the price of

credit is too low for a period of time, as is the case with

a promotional introductory oer, credit card customers

borrow too much: The benet that accrues to them exceeds

the cost implied for the lender by the fact that the customer

may default on this amount later on. Rational borrowers

realize that this cost must eventually be passed onto them

because lenders must break even, and for this reason they

prefer at schedules. The key virtue of a competitive market

is that competition between lenders drives down prices to

a common break-even point, which implies that, to attract

customers, lenders must oer the product that best suits

the customer.

So why do we keep nding zero- oers in our mail-

boxes? Research in behavioral economics may have the

answer. This research suggests that zero may indeed

let people “believe what they want to believe.”

The best-known piece of evidence supporting this theory

comes from an inuential albeit unpublished study by

University of Maryland economists Lawrence M. Ausubel

and Haiyan Shui. In collaboration with a major credit

card issuer, Ausubel and Shui performed a unique study

of credit card marketing that involved an experiment of

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Research Department

Why Credit Cards Played a Surprisingly Big Role in the Great Recession

2021 Q2

11

simultaneously mailing several dierent oers to tease out

customer bias for promotional introductory oers. In

cooperation with the issuer, the researchers tracked the

activity on the accounts after the oers were accepted.

To assess the customer’s choice, they also calculated the

interest rate payments the customer would have faced

had they chosen a dierent oer.

Surprisingly, customers on average chose what the

rational model would deem a “wrong” oer. More

importantly, they were not simply accepting oers at ran-

dom, possibly ignoring the oered terms; to the contrary,

customers were attracted to oers that minimized their

immediate interest payments, even if choosing such oers

cost them more later. Ausubel and Shui concluded that

consumers fail to accurately predict their future behavior,

which leads them to erroneously think that they are pick-

ing the best oer.

In particular, Ausubel and Shui have demonstrated that

the results of their experiment are consistent with naiveté

hyperbolic discounting—the leading theory of consumer

myopia put forth by Harvard economist David Laibson and

earlier shown successful in addressing several puzzling

observations in consumer credit markets. According to this

theory, borrowers have an idealistic view of their future

self, incorrectly believing that their future self will have

almost no debt and pay no interest. This idealistic view

leads them to underestimate the burden of the interest-

rate hike associated with the expiration of an introductory

oer. As a result, they prefer introductory oers and under-

estimate the signicance of these oers’ high reset rates.

Ausubel and Shui also found that this theory ts the

data well for parameter values consistent with earlier work

with this model. By assuming the same parameter values,

Michal Kowalik and I showed that this theory can explain

the widespread use of zero in the U.S. credit card

market, where competitive lenders are free to design the

credit card oers they send to consumers.

Of course, the fact that the leading theory of consumer

myopia may explain the U.S. credit card market doesn’t

imply that the entire population is prone to zero- oers.

It may be that credit card customers who did not accept

a zero- oer in the Ausubel and Shui study are the ratio-

nal ones and only the overoptimistic found promotional

oers particularly attractive, leading to selection bias among

study respondents. Their nding only shows that there are

enough customers prone to these oers to drive promo-

tional lending.

The Makings of a Perfect Storm

Before my work with Kowalik, surprisingly little was known

about the prevalence of promotional oerings in the U.S.

credit card market and their eect on the functioning of

the market. Data provided by the three credit bureaus lack

interest rates, and their data are the most comprehensive

commercially available source of information about credit

market activity in the U.S. Without interest rate data, we

can’t study promotional activity as carefully as we would

like, and consequently we did not know much about it.

In our work, for the rst time, we could uncover evidence

of the widespread and intricate use of promotional lending

owing to the availability of regulatory account-level

data covering the majority of the general-purpose credit

card accounts in the U.S. right before the nancial

crisis—a data set large and detailed enough to character-

ize promotional lending in the economy as a whole.

Although we suspected some use of introductory oers to

reduce interest rate payments, what we found surpassed

our expectations.

By , the credit card market was essentially in the

grips of zero- oers, with a vast amount of credit card

debt being de facto short-term debt and prone to disrup-

tions during crises. In particular, as of the rst quarter

of , we found that percent of credit card debt held

on general-purpose credit card accounts was on pro-

motional terms with rates close to zero, with an average

yearlong expiration of the promotional terms. Among

prime borrowers with a good credit history (that is, a credit

score above ), the percentage was even higher:

percent. When we factored in a typical fee of percent for

transferring funds at the time, and a rate on the pro-

motional debt near zero, promotional accounts provided

an average discount of about percentage points from the

average reset rate on those accounts—and a similar discount

vis-à-vis the average interest rate paid on nonpromotional

credit card debt. This was true for both the prime segment

and the whole market, which shows that promotional debt

importantly contributed to making credit card debt

aordable to borrowers.

Crucially, balances that fed promotional accounts before

the crisis were mainly transfers of debt from other accounts—

as opposed to debt accrued from purchases using the new

card.

This nding implies that consumers were not only

using promotion on a massive scale but also moving

funds to reduce the interest rate paid on their credit card

debt, something we corroborated by showing that some

borrowers were chaining promotional cards to extend the

duration of promotional rates. As for the market as a whole,

this observation is key, since it implies that at the onset

of the Great Recession the aordability of credit card debt

hinged on an uninterrupted ow of promotional oers.

Three percent on zero may not sound like enough

for lenders to be able to break even, but lenders too could

prot on the promotional oers, since they attract borrow-

ers who later may have to pay the reset rate on the account

when they are unable to switch to a new card or when their

rate resets early because they violated the contract’s “ne

print.” Basic economic theory implies that lenders put up

with this behavior precisely because they could break even

and borrowers preferred such oers.

As explained earlier,

a competitive market leads to the outcome that best suits

the borrowers, and the evidence suggests that promotional

oers suited them best.

12

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Research Department

Why Credit Cards Played a Surprisingly Big Role in the Great Recession

2021 Q2

county relative to other counties. This we did see, indicating

that the nancial sector’s credit crunch was in part responsible

for the declining share of promotional balances.

Of course, other factors may have also contributed to the

decline in the availability of promotional credit card oers, and

our research design does not allow us to quantitatively assess

the relative importance of those factors. The most straightfor-

ward reason is that lenders might have discontinued promotional

oers because they themselves feared a recession-related spike

in defaults on credit card debt due to falling incomes and employ-

ment. Credit card debt is unsecured, which is one reason why

default rates spike during recessions. By reducing credit during

a recession, banks can avoid losses from rising defaults.

Connecting the Dots

The second half of was a turning point for credit card

borrowing overall.

Credit card debt, despite rising steadily for

decades, fell markedly relative to median household income and

other types of consumer debt (Figure ). In our work, Kowalik

and I have hypothesized that the decline in credit card borrow-

ing relative to the previous trend was driven by the collapse of

promotional oerings, which then led credit card customers to

either default on debt more frequently or make early debt repay-

ments, contributing to the decline of aggregate demand during

the Great Recession.

It’s dicult to assess exactly

how much the collapse in pro-

motional oerings contributed

to the decline in credit card

The Perfect Storm

The September collapse of Lehman Brothers, by triggering

a panic within the nancial sector, set the stage for a perfect storm

in the credit card market. Starved for liquidity, and expecting a

recession that would harm consumers, the nancial sector tight-

ened the supply of credit to rms and households, whereupon

many credit card borrowers suered because of their heavy

reliance on the constant ow of promotional oers to reduce

interest payments.

The data show that preapproved and prescreened promotional

balance-transfer oers had fallen more than percent by mid-

(Figure ), suggesting that many credit card borrowers who

had previously hoped to transfer balances onto a promotional

account might have had trouble getting a new card during the

crisis.

Consistent with the decline in mail-in oers, promotional

balance transfers dived, falling percent by early (Figure

). Not surprisingly, the fraction of promotional debt began to

decline, bottoming out in at about half of its precrisis value

of percent. This was true for all accounts in our sample as well

as just those with a good credit history (Figure ).

Kowalik and I further investigated to what extent the deterior-

ating nancial health of the lenders might have driven the decline,

which is a proxy for the impact of the crisis on each individual

lender’s nancing conditions. We analyzed how the county-level

credit card lender health index, which we constructed, correlates

with the decline in the share of promotional debt and balance

transfers in each county. If a credit card issuer has a large

presence in a U.S. county, and if its nancial health worsens

more than that of creditors in other counties, we should see

a larger decline in balance transfers and promotional debt in that

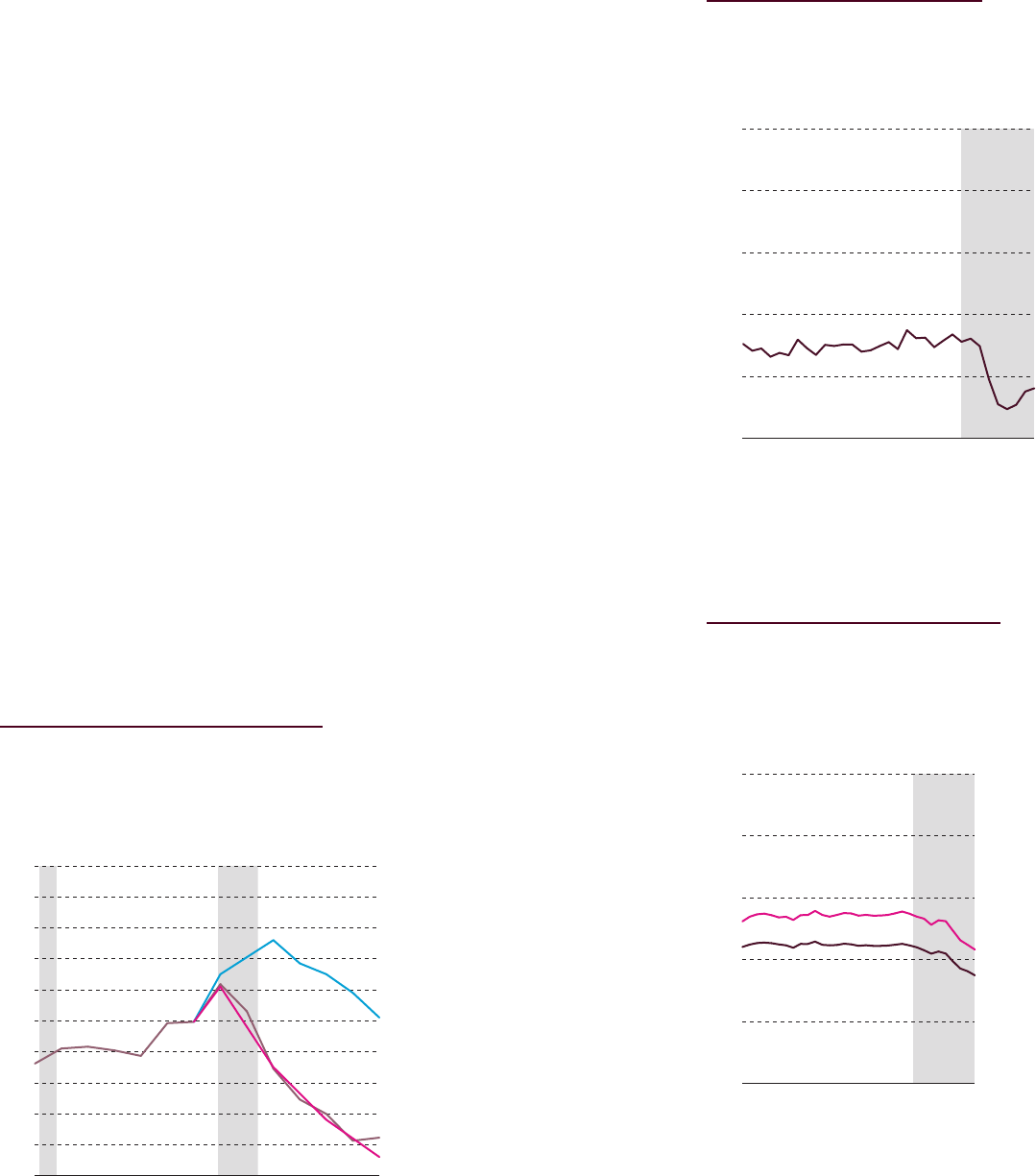

FIGURE 3

Recession Brought an End to the

Abundance of Zero-APR Oerings…

Number of mail-in preapproved credit card solicitations

with a promo balance transfer oer, in millions,

2007–2013

FIGURE 4

…Promotional Balance Transfers

Collapsed…

Promotional balance transfers as a percentage of

credit card debt outstanding, annualized, 2008–2013

FIGURE 5

…and the Share of Promotional

Card Debt Began to Shrink…

Promotional credit card debt as a percentage of credit

card debt outstanding, all accounts and accounts

with at least a 670 credit score, 2008–2013

Source: Federal

Reserve, .

Source: Mintel Compremedia

Inc., Direct Mail Monitor Data.

Source: Federal

Reserve, .

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

Jan

2008

Jun

2009

Oct

2013

Jan

2008

Jun

2009

Oct

2013

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Jan

2008

Oct

2013

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Credit score

670+

All accounts

Jun

2009

See How Chaining of Zero-

APR Oers May Amplify

a Recession.

Notes: The sample

includes six largest banks,

eight banks in total; gray bar

indicates recession.

Note: Gray bar

indicates recession.

Notes: The sample

includes six largest banks,

eight banks in total; gray bar

indicates recession.

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Research Department

Why Credit Cards Played a Surprisingly Big Role in the Great Recession

2021 Q2

13

FIGURE 6

... which Turned the Decades-Long

Borrowing Boom into a Bust

Actual and model-predicted credit card debt per

adult as percentage of median personal income,

2001–2014

FIGURE 7

The COVID-19 Recession Had

a Similar Eect on Balance

Transfers…

Promotional balance transfers as a percentage of

credit card debt, annualized, 2018–2020

FIGURE 8

... and the Share of Promotional

Debt Also Began to Shrink

Promotional credit card debt as a percentage of credit

card debt outstanding, all accounts and accounts

with at least a 670 credit score, 2018–2020

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, G. Consumer Credit, Total

Revolving Credit Owned and Securitized, Outstanding [], , Federal Reserve Bank

of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/REVOLSL. U.S. and Census Bureau, Current

Population Survey, March and Annual Social and Economic Supplements, and earlier.

Source: Federal Reserve System, .

Notes: The data in Figure pertain to a smaller sam-

ple of eight banks and are not directly comparable to

data in the figure; gray bar indicates recession.

Source: Federal Reserve System, .

Note: Gray bar indicates recession.

2001 2008 2014

15%

17%

19%

18%

16%

21%

23%

24%

22%

20%

25%

Data

Model Prediction:

Recession and

Zero-APR crisis

Model Prediction:

Just recession

to the same ratio in the data. This ratio

is an imperfect proxy for consumption-

depressing factors other than declining

income, which may be a product of

the recession itself and not a trigger. We

estimated that, according to our model,

peak-to-trough, the decline in the availa-

bility of promotional oerings contributed

to about a quarter of the decline in this

ratio from through .

The COVID19 Crisis:

A Silent Alarm?

Fast-forward to and both balance-

transfer activity and zero- oers have

not rebounded to their respective

levels (Figure ), which has made the

credit card market more stable. We do not

know why the decline has persisted for

so long after the recession, but the most

prosaic explanation may be the right one:

Having had a bad experience with zero

, borrowers avoided such oers after

the Great Recession. Nonetheless, promo-

tional activity and balance transfers did

not disappear and may rise again in the

future, which raises the question: How

has promotional credit card lending fared

during the more recent - crisis?

borrowing or consumption demand. In

the data, both the collapse in oerings

and the decline in borrowing or con-

sumption involve changes that triggered

the recession and changes that were the

product of the recession. For example,

such a decline may have been partly due

to a hike in defaults on credit card debt

triggered by job losses during the Great

Recession, which was part of a feedback

mechanism rather than the trigger.

To isolate the contribution of the with-

drawal of promotional oers, Kowalik and

I used an economic model of the credit

market that replicates what happened

during the Great Recession. Using the

model, we asked, what would have hap-

pened had fairly priced promotions held

steady during the recession?

The results we found were troubling.

According to the model, there would have

been no decline from the precrisis trend

in the ratio of median personal income

to credit card debt per adult. Indeed, the

ratio would have gone up (Figure ).

But was the collapse in promotional

oerings enough to aect consumption

demand across the economy? To nd out,

we also compared the model’s ratio of ag-

gregate consumption to disposable income

Note: Model predictions

are approximate due to

minor dierences in data

formatting and sources.

For detailed analysis, see

my work with Kowalik

().

Feb

2018

Oct

2020

Feb

2020

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

Feb

2018

Oct

2020

Feb

2020

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

All

accounts

Credit

score

670+

14

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Research Department

Why Credit Cards Played a Surprisingly Big Role in the Great Recession

2021 Q2

How Chaining of Zero-APR Oers May Amplify a Recession

Here is how credit card borrowers chain

promotional zero- oers: First, they

charge purchases on their zero- credit

card. Then, before the card’s new, higher

base rate kicks in, they apply for another

zero- card and transfer the debt to the

new card. In eect, they are extending

the duration of the promotional interest rate.

For economists, there is nothing unusual

about “chaining” of promotional credit card

oers. It’s just another instance of borrowing

via rolling over short-term debt obligations—

a widespread practice across the economy.

However, this type of borrowing is known

to be vulnerable to disruptions of the credit

supply and may trigger or contribute to

a recession, which is why it is monitored

and regulated as part of macroprudential

policies. (See Endnote for an explanation

of macroprudential regulation.)

Here is how it happens. Consider a situation

where a borrower takes out a long-term

loan and borrows for two periods from Bank

A using two dierent strategies. In the first

situation (Case I), debt does not become due

until Period , and Bank A cannot request

funds early. In the second situation (Case II),

the borrower “chains” lenders by repaying

Bank A with funds borrowed from Bank B

in Period . Both cases lead to the same

outcome when credit flow is uninterrupted:

The borrowers borrow in the first period

and repay in the third, eectively borrowing

funds for a duration of two periods. But the

second case (Case II) is vulnerable to a credit

supply disruption and the first is not. Say, for

example, that in Period , banks decide not

to lend as much, so that the borrower in Case

II has a hard time finding another lender

(Figure ). This borrower will be forced to

repay debt early and cut down on their

spending on purchases of goods and ser-

vices. Alternatively, the borrower, unable

to make the payment, will default on their

debt, in which case Bank A will be hurt and

will possibly reduce the credit supply to

other customers, which will hurt their con-

sumption (or investment). In both situations,

if banks, amid a recession, withdraw funds

from the market to reduce their losses, they

may amplify that recession due to reduced

consumption or investment demand.

Case I

Long-term

Lending

Case II

Chain

Lending

Case I

Long-term

Lending

Case II

Chain

Lending

Bank B loans to

Borrower for one

period, which

Borrower uses to

repay Bank A

and Borrower

spends on goods

and services

But What Might Happen If the Credit Supply Is Disrupted in Period 2?

Borrower repays

Bank A in Period 3

$

$

$

PERIOD 1 PERIOD 2 PERIOD 3

Borrower repays

Bank B in Period 3

$

Option 1

Reduce spending on goods and services to

repay Bank A’s loan early

Because the Borrower does not need a loan

in Period 2, the outcome is the same.

Bank A loans to Borrower

for two periods to spend

on goods and services

$

Bank A

Bank A loans to Borrower

for one period to spend

on goods and services

$

Bank A

Bank A loans to Borrower

for one period to spend

on goods and services

$

Bank A

$

$

$

$

If Bank B rejects the loan application, Borrower has

two options that will both be recessionary:

Option 2

Default on loan repayment, forcing Bank A to

reduce loans to other borrowers and hurting

creditworthiness in the economy

Borrower

spends on

goods and

services

FIGURE 9

Chain Lending and How It Might Amplify a Recession

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Research Department

Why Credit Cards Played a Surprisingly Big Role in the Great Recession

2021 Q2

15

The answer to this question is important because it

helps us address another question: How vulnerable is

promotional lending during a recession not triggered

by a nancial crisis?

Credit markets fared well during the crisis, but as

for promotional credit cards, the data from the

rst half of are troubling because it suggests that

promotional oerings might have been similarly

depressed, and the overall impact of this development

was lower because the starting volume was lower.

In particular, the data for the rst half of show

a modest percentage point decline in the share

of promotional debt, which fell from about percent

prior to the Great Recession to about by October

(Figure ). Worryingly, the decline in promo-

tional balance transfers is almost as striking as during

the Great Recession, falling by over percent peak

to trough, albeit from a volume that is less than a third

of that at the onset of the Great Recession (Figure ).

As more data become available, we will be able

to examine this crisis more closely, but the early

indication is that promotional credit card borrowing

is vulnerable during recessions that do not involve

a nancial crisis.

Conclusion

The nancial crisis taught us that the prolifer-

ation of zero on balance transfers can threaten

economic stability. The - crisis reminds

us that a signicant fraction of debt still originates as

promotional transfers, and nothing prevents that

fraction from rising again. At the very least, then, the

volume of zero- debt and balance transfers should

be carefully monitored. The credit card market is

now large enough to aect the whole economy, and

policymakers should keep it in mind when they craft

their regulatory agendas.

Laissez faire theory holds that, if both sides of

a market transaction decide to use a particular credit

instrument, this credit instrument is likely socially

benecial, and the government shouldn’t regulate it.

But the research points to the role of awed human

psycholoy in the rise of zero- oers, and this

should raise concerns about the application of the

laissez faire principle. What’s also worrisome is that

the way lenders break even falls outside of the con-

tract. For example, consumers may get hit with the

reset rate when they cannot nd another oer, or

when they violate the contract’s “ne print,” thus

exposing themselves to an imminent and unexpected

rate hike on debt. The contract doesn’t specify how

much they will pay for borrowing—a departure from

how most loan contracts are written. Such an arrange-

ment is conducive to abuse and predatory practices.

Notes

1 Macroprudential regulation of credit markets is

an approach to regulation guided by the principle

of mitigating risks to the financial system

and the economy as a whole. Stress testing

of banks to ensure their resilience in times of

distress is an example of macroprudential

regulation implemented in the aftermath of the

Great Recession by the Dodd–Frank Wall Street

Reform and Consumer Protection Act of .

2 For an accessible discussion, see the Econo-

mic Insights article by my colleague Ronel Elul.

See also the work by Gilchrist, Siemer, and

Zakrajsek; Mondragon; and Aladangady. The

study by Mian and Sufi initially suggested

a modest role for credit markets.

3 The annual percentage rate () refers to

the annual rate of interest charged to borrow-

ers for carried-over balances after the credit

card statement closes. In a zero- oer, the

credit card holder pays no interest on charges

to their credit card for an introductory period.

Thereafter, a new kicks in for the outstand-

ing balance and all future charges.

4 Usury laws govern the maximum amount of

interest that can be charged on a loan.

5 High levels of fraud and defaults also con-

tributed to low profits during this early period.

See Evans and Schmalensee (page ) for

more details.

6 According to the court's unanimous opinion,

the National Bank Act of created a path

toward a national consumer lending economy.

7 See Livshits, MacGee, and Tertilt; Drozd and

Serrano-Padial; and Athreya, Tam, and Young

for detailed analyses of the growth of credit

card borrowing in the U.S. Jaromir Nosal and

I provide an analysis of how a decline in the

fixed cost of lending leads to an expansion in

access to lending.

8 According to data from the Survey of Con-

sumer Finances (), the mean credit card

debt per household whose income is close to

the median (that is, between the th and

th percentiles of income) has been almost

identical to the overall mean credit card debt

per household between and . This is

not true for income. In the same data source,

income per household close to the mean was

lower by percent in and by percent

16

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Research Department

Why Credit Cards Played a Surprisingly Big Role in the Great Recession

2021 Q2

19 Consider a situation in which a borrower is encouraged to draw an

additional dollar of debt because of a low promotional interest rate. Sup-

pose this borrower will default on this additional dollar of debt when they

lose their job. In a competitive market, the borrower must compensate

the lender by paying more interest in the future for the additional risk of

default because the lender must break even on average. In the model, the

additional benefit from the dollar when the borrower becomes unem-

ployed outweighs the cost of paying more interest when the borrower

keeps their job—an eect that makes introductory oers suboptimal for

rational borrowers.

20 The evidence that Ausubel and Shui found has been confirmed in

other studies, which point to similar biases in investing and saving

behavior. For example, in a closely related study, Agarwal et al. show

that credit card customers prefer low-annual-fee cards, even though

they end up later overpaying in interest in excess of the fee.

21 Promotional lending can be studied using proprietary account-level

data, but such data are typically not available at a scale that allows

researchers to see how borrowers transfer balances across accounts

and lenders. Prior to the Dodd–Frank Act, the was the only institution

we knew of that possessed an account-level data set covering a large

fraction of U.S. credit card accounts. The Federal Reserve System later

acquired this data set for its stress testing. The numbers reported in this

article come from this merged data set.

22 These data are collected by the Federal Reserve System under

Dodd–Frank to help the Fed conduct stress testing of banks. The data are

available for economic research conducted within the Federal Reserve

System, providing new insights into the inner workings of credit markets.

23 See figures in my work with Kowalik.

24 Our data does not allow us to calculate lender costs on the account

level, and it is not possible to precisely assess profitability of zero-

accounts. Initially, lenders do lose money on zero- accounts in the

data, but over time we did not find any indication that these accounts

are less profitable than comparable accounts.

25 Prescreened oers mailed out by credit card issuers are the main tool

of customer acquisition in the credit card market, so the number of mailed-

out solicitations is a reliable measure of the credit card industry’s hunger

for new customers. Evans and Schmalensee report that in the early s

about percent of credit accounts were initiated via prescreened oers.

26 Using a dierent approach, Keys, Tobacman, and Wang reach a similar

conclusion.

27 Credit card borrowing takes place when a credit card holder does

not pay back the balance in full after the credit card statement closes

and “rolls over” the outstanding balance to the next billing cycle

(partly or fully).

28 Consumption demand was an important factor in the Great Recession.

Mian and Sufi have shown that the decline in consumption was key to

explaining the fall in aggregate demand.

in the s. This shows that income is more concentrated at the top of

the income distribution than debt, and hence the burden of debt for the

majority of households is best captured by using median income instead

of mean income. For more details on the income growth among top earn-

ers, see the Economic Insights article by my colleague Makoto Nakajima.

9 See my work with Ricardo Serrano-Padial for more details on the con-

nection between debt collection and credit card lending.

10 See my work with Ricardo Serrano-Padial. “Default risk” measures

the fraction of debt that lenders expect will not be paid back because

some credit card borrowers may default, and debt may be deemed

nonrecoverable. Because credit card debt is unsecured, and debt can

be discharged in court, default risk is substantial on credit cards. One

measure of default risk is the so-called charge-o rate on a credit card

debt portfolio: the fraction of debt charged o the creditor’s books after

days of being delinquent during a period, net of any recovered and

previously delinquent debt over the same period.

11 See the article by James J. Daly. In their monograph, Evans and

Schmalensee report very similar numbers in the credit card market for

the preceding year.

12 In , Capital One became the first issuer to introduce a balance-

transfer oer.

13 Evans and Schmalensee report that, by the s, percent of

credit accounts were initiated via prescreened oers.

14 The company was known to use advanced (for that time) modeling to

thoroughly understand the behavior of its customers. See online post by

Andrew Becker.

15 The memos were published by the San Francisco Chronicle after a year-

long legal battle with Providian to make them public. Excerpts of the

released memos can be found in the Chronicle article by Sam Zuckerman.

16 The interview appears in the Frontline documentary “Secret

History of the Credit Card.” The documentary can be found at https://

www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/credit/.

17 Providian settled in for $ million after already reimbursing

customers at least $ million. The company was sold to Washington

Mutual in for approximately $. billion. Its credit card portfolio

at the time amounted to million card holders.

18 In the case of credit cards, the risk of default is significant given

the unsecured nature of credit card debt. Borrowers may default on un-

secured debt by filing for bankruptcy. Since the borrower does not have

to oer collateral as potential compensation to the lender, the lender is

at risk of never receiving payment on the principal amount owed. And,

even if the borrower does not file for bankruptcy, their (usually) small

amount of debt may make debt collection prohibitively costly for the

lender, leading to a widespread phenomenon of “informal bankruptcies.”

For more details, refer to my work with Ricardo Serrano-Padial.

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Research Department

Why Credit Cards Played a Surprisingly Big Role in the Great Recession

2021 Q2

17

References

Agarwal, Sumit, Souphala Chomsisengphet, Chunlin Liu, and Nicholas

S. Souleles. “Do Consumers Choose the Right Credit Contracts?”

Review of Corporate Finance Studies, (), pp. –, https://doi.

org/./rcfs/cfv.

Aladangady, Aditya. “Housing Wealth and Consumption: Evidence From

Geographically-Linked Microdata,” American Economic Review, :

(), pp. –, https://doi.org/./aer..

Aruoba, S. Borağan, Ronel Elul, Şebnem Kalemli-Özcan. “How Big Is the

Wealth Eect? Decomposing the Response of Consumption to House

Prices,” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Working Paper No. -

(), https://www.philadelphiafed.org/consumer-finance/mortgage-

markets/how-big-is-the-wealth-eect-decomposing-the-response-of-

consumption-to-house-prices.

Athreya, Kartik, Xuan S. Tam, and Eric R. Young. “A Quantitative Theory of

Information and Unsecured Credit,” American Economic Journal: Macro-

economics, : (), pp. –, https://doi.org/./mac....

Ausubel, Lawrence M., and Haiyan Shui. “Time Inconsistency in the

Credit Card Market,” University of Maryland Department of Economics

working paper ().

Becker, Andrew. “The Battle over ‘Share of Wallet’,” Public Broadcasting

Service (), Frontline, November , , https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/

pages/frontline/shows/credit/more/battle.html.

Daly, James J. “Smooth Sailing,” Credit Card Management, : (),

pp. –.

Drozd, Lukasz, and Michal Kowalik. “Credit Cards and the Great Recession:

The Collapse of Teasers,” unpublished manuscript (), https://www.

lukasz-drozd.com/uploads//////drozd-kowalik-v.pdf.

Drozd, Lukasz, and Jaromir Nosal. “Competing for Customers: A Search

Model of the Market for Unsecured Credit,” unpublished manuscript

().

Drozd, Lukasz, and Ricardo Serrano-Padial. “Modeling the Revolving

Revolution: The Debt Collection Channel,” American Economic Review,

(March ), pp. –, https://doi.org/./aer..

Elul, Ronel. “Collateral Damage: House Prices and Consumption During

the Great Recession,” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Economic

Insights (Third Quarter ), pp. –, https://www.philadelphiafed.org/

the-economy/macroeconomics/collateral-damage-house-prices-and-

consumption-during-the-great-recession.

Evans, David S., and Richard Schmalensee. Paying with Plastic: The Digital

Revolution in Buying and Borrowing. Cambridge, MA: The Press, .

Gilchrist, Simon, Michael Siemer, and Egon Zakrajsek. “The Real Eects

of Credit Booms and Busts: A County-Level Analysis,” discussion paper,

mimeo ().

Haltom, Renee, and John A. Weinberg. “Does the Fed Have a Financial

Stability Mandate?” Economic Brief EB-, Federal Reserve Bank of

Richmond, June .

Keys, Benjamin, Jeremy Tobacman, and Jialan Wang. “Rainy Day Credit?

Unsecured Credit and Local Employment Shocks,” unpublished manu-

script ().

Laibson, David, Andrea Repetto, and Jeremy Tobacman. “Estimating

Discount Functions with Consumption Choices Over the Lifecycle,”

Working Paper (), https://doi.org/./w.

Laibson, David. “Golden Eggs and Hyperbolic Discounting,” Quarterly

Journal of Economics, : (), pp. –, https://doi.org/./

.

Livshits, Igor, James C. Mac Gee, and Michèle Tertilt. “The Democra-

tization of Credit and the Rise of Consumer Bankruptcies,” Review of

Economic Studies, : (), pp. –, https://doi.org/./

restud/rdw.

Mian, Atif, and Amir Sufi. “What Explains the – Drop in Em-

ployment?” Econometrica, :, (), pp. –, https://doi.org/

./ECTA.

Mondragon, John. “Household Credit and Employment in the Great

Recession,” Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University,

mimeo ().

Nakajima, Makoto. “Taxing the Percent,” Federal Reserve Bank of

Philadelphia Economic Insights (Second Quarter ), pp. –, https://

www.philadelphiafed.org/the-economy/macroeconomics/taxing-the--

percent.

Zuckerman, Sam. “How Providian Misled Card Holders,” San Francisco

Chronicle, May , , https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/How-

Providian-misled-card-holders-.php.