Strategies toward ending

preventable maternal

mortality (EPMM)

Strategies toward ending

preventable maternal

mortality (EPMM)

PHOTO CREDITS (top to bottom)

• Karen Kasmauski/MCSP

• UNICEF/Dormino

• Shaqul Alam Kiron/MCHIP

WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM).

1.Maternal Death – prevention and control. 2.Maternal Mortality – prevention and control. 3.Obstetric Labor

Complications – prevention and control. 4.Maternal Health Services – standards. 5.Health Services Accessibility.

6.Universal Coverage. I.World Health Organization.

ISBN 978 92 4 150848 3 (NLM classication: WQ 270)

© World Health Organization 2015

All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO website (www.who.int)

or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland

(tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857;

e-mail: bookorders@who.int).

Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for non-commercial

distribution– should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (www.who.int/about/licensing/copy-

right_form/en/index.html).

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of

any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country,

territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and

dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specic companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed

or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not men-

tioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained

in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either

expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no

event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use.

iii

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Contents

Abbreviations 1

Introduction 2

Background 3

Lessons learned: successes and challenges 3

Way forward 4

Targets for maternal mortality reduction post-2015 6

Global targets to increase equity in global MMR reduction 6

Country targets to increase equity in global MMR reduction 6

Establishment of an interim milestone to track progress toward the ultimate MMR target 7

Strategic framework for policy and programme planning to achieve MMR targets 8

Laying the foundation for the strategic framework 8

Guiding principles, cross-cutting actions and strategic objectives for policy and

programme planning 9

Guiding principles for EPMM 10

Empower women, girls, families and communities 10

Integrate maternal and newborn care, protect and support the mother–baby relationship 10

Prioritize country ownership, leadership and supportive legal, regulatory and nancial

mechanisms 11

Apply a human rights framework to ensure that high-quality sexual, reproductive,

maternal and newborn health care is available, accessible and acceptable to all

who need it 12

Cross-cutting actions for EPMM 14

Improve metrics, measurement systems and data quality 14

Prioritize adequate resources and eective health care nancing 15

iv

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Elaboration of the ve strategic objectives to guide programme planning

towards EPMM 18

1. Address inequities in access to and quality of sexual, reproductive, maternal and newborn

health care 18

2. Ensure universal health coverage for comprehensive sexual, reproductive, maternal

and newborn health care 19

3. Address all causes of maternal mortality, reproductive and maternal morbidities

and related disabilities 20

4. Strengthen health systems to respond to the needs and priorities of women and girls 25

5. Ensure accountability to improve quality of care and equity 26

Conclusion 28

Acknowledgements 29

Annex 1. Goal-setting for EPMM: process and timeline 30

Annex 2. Accelerating reduction of maternal mortality strategies and targets

beyond 2015: 8–9 April 2013, Geneva, Switzerland 31

Annex 3. Targets and strategies for ending maternal mortality:

16–17 January 2014, Geneva, Switzerland 33

Annex 4. Country consultation on targets and strategies for EPMM.

14–16 April, 2014, Bangkok, Thailand 35

References 41

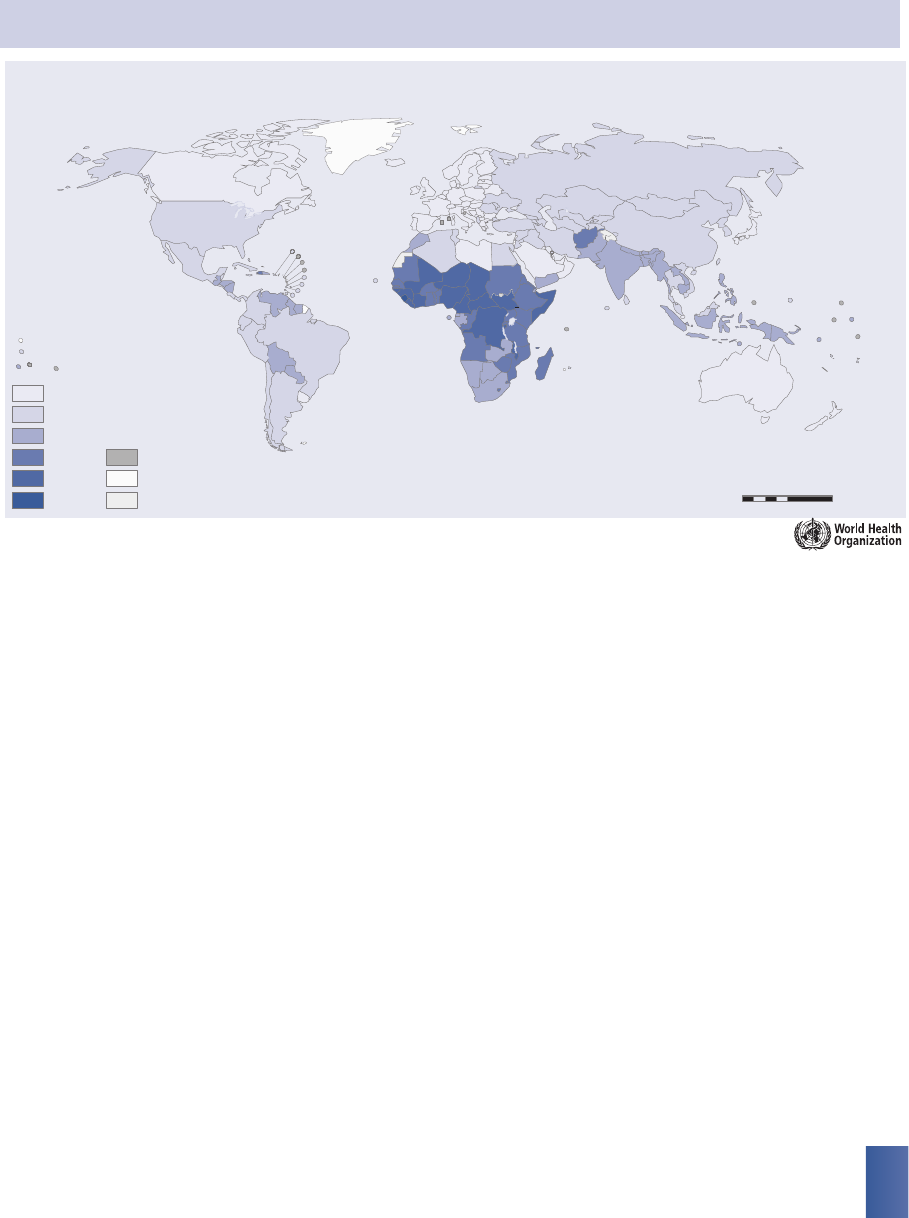

Figure 1:

Maternal mortality ratio (MMR, per 100 000 live births stratied by MMR level)

3

Figure 2:

MMR reduction at country level 7

Figure 3:

Global estimates for causes of maternal mortality 2003–2009 20

Box 1:

Population dynamics 5

Box 2:

Ultimate goal of EPMM 9

Box 3:

Rationale and scope of strategic objectives for EPMM 16

Box 4:

Evidence-based resources for planning key interventions 22

1

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Abbreviations

AAAQ availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of services

AMDD Averting Maternal Death and Disability program

ARR annual rate of reduction

CEDAW Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Woman

ENAP Every Newborn Action Plan

EPMM eliminating ending preventable maternal mortality

GFF Global Financing Facility

HIV human immunodeciency virus

HRC United Nations Human Rights Council

HRP Human Resource Planning

IHI Institute for Healthcare Improvement

MCHIP Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program

MDG Millennium Development Goal

MDSR maternal death surveillance and response

MHTF Maternal Health Task Force

MMR maternal mortality ratio

OHCHR Oce of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

PMNCH Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

RHR Reproductive Health and Research

SRMNCAH sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, child, and adolescent health

UHC universal health coverage

UN United Nations

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

USAID US Agency for International Development

WASH water, sanitation and hygiene

WHO World Health Organization

2

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Introduction

As the 2015 target date for the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) nears, ending preventa-

ble maternal mortality (EPMM) remains an unnished agenda and one of the world’s most critical

challenges despite signicant progress over the past decade. Although maternal deaths world-

wide have decreased by 45% since 1990, 800 women still die each day from largely preventable

causes before, during, and after the time of giving birth. Ninety-nine per cent of preventable

maternal deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries

(1)

. Within countries, the risk of death

is disproportionately high among the most vulnerable segments of society. Maternal health,

wellbeing and survival must remain a central goal and an investment priority in the post-2015

framework for sustainable development to ensure that progress continues and accelerates, with

a focus on reducing inequities and discrimination. Attention to maternal mortality and morbidity

must be accompanied by improvements along the continuum of care for women and children,

including commitments to sexual and reproductive health and newborn and child survival.

The time is now to mobilize global, regional, national and community-level commitment for

EPMM. Analysis suggests that “a grand convergence” is within our reach, when through con-

certed eorts we can eliminate wide disparities in current maternal mortality and reduce the

highest levels of maternal deaths worldwide (both within and between countries) to the rates

now observed in the best-performing middle-income countries

(2)

. To do so would be a great

achievement for global equity and reect a shared commitment to a human rights framework

for health.

High-functioning maternal health programmes require awareness of a changing epidemiolog-

ical landscape in which the primary causes of maternal death shift as maternal mortality ratios

(MMRs) decline, described as “obstetric transition”

(3)

. Strategies to reduce maternal mortality

must take into account changing patterns of fertility and causes of death. The ability to count

every maternal and newborn death is essential for understanding immediate and underlying

causes of these deaths and developing evidence-informed, context-specic programme inter-

ventions to avert future deaths.

The EPMM targets and strategies are grounded in a human rights approach to maternal and

newborn health, and focus on eliminating signicant inequities that lead to disparities in access,

quality and outcomes of care within and between countries. Concrete political commitments

and nancial investments by country governments and development partners are necessary to

meet the targets and carry out the strategies for EPMM.

3

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Background

Lessons learned: successes and challenges

MDG 5a calls for a 75% decrease in MMR from 1990 to 2015. By 2013, a 45% reduction was

achieved (from 380 deaths/100 000 live births in 1990 to 210 deaths/100 000 live births), show-

ing signicant progress but still falling far short of the global goal.

To achieve the MDG target, each country was required to maintain an average annual rate of

reduction (ARR) in MMR of 5.5%. Instead, the average ARR among countries between 1990 and

2013 was only 2.6%. However, countries showed that with commitment and eort, they could

accelerate the pace of progress: the average ARR increased to 4.1% during 2000–2010 from just

1.1% during 1990–2000. Moreover, 19 countries sustained an average ARR of over 5.5% for every

year from 1990 to 2013; the highest average ARR ranged from 8.1% to 13.2%

(4)

.

MDG 5b calls for universal access to reproductive health for all women by 2015, as measured

by antenatal care coverage, contraceptive prevalence, unmet family planning need and ado-

lescent birth rates. As of 2014, although gains were made in each category, insucient and

greatly uneven progress was measured by each of these indicators

(5)

. Far more work is needed

to ensure that all women receive basic preventive and primary reproductive health care services,

including preconception and interconception care, comprehensive sexuality education, family

planning and contraception, as well as adequate skilled care during pregnancy, childbirth and

0 1,750 3,500875 Kilometers

Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births), 2013

Data Source: World Health Organization

Map Production: Health Statistics and

Information Systems (HSI)

World Health Organization

The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever

on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities,

or concerning th

e d

elimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines

for which there may not yet be full agreement.

© WHO 2014. All rights reserved.

<20

20–99

100–299

300–499

500–999

≥1000

Population <100 000 not included in the assessment

Data not available

Not applicable

FIGURE 1: Maternal mortality ratio (MMR, per 100 000 live births stratied by MMR level)

(4)

4

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

the postpartum period. Further attention is needed to develop valid metrics and improve data

quality to measure access to reproductive health for women and girls.

The MDGs mobilized resources as well as political will in countries, and made global commitments

to improve sexual and reproductive health, and maternal and child survival to an unprecedented

degree. They demonstrated that shared global goals, targets and strategies could galvanize

the concerted eort needed to achieve measurable progress. Low- and middle-income coun-

tries that have made rapid progress toward achieving MDG 5 used unique strategies tailored to

local needs and contexts. They all used multisector approaches and catalytic strategies to trans-

late evidence into strong programming based on clearly articulated guiding principles

(6)

. The

progress made has brought the “grand convergence” of health outcomes into view, making it

possible to envision a world in which low-, middle- and high-income countries have compara-

ble rates of maternal mortality

(2)

.

At the same time, there are signicant lessons to be learned. The MDG framework has been crit-

icized for giving rise to a fragmented approach to health planning that has not encouraged

intersectoral collaboration or programme integration to improve coordination, innovation and

eciency. Furthermore, the MDGs paid insucient attention to development principles, such as

human rights, equity, poverty reduction, empowerment of women and girls and gender equality.

The focus on national averages may have resulted in prioritization of conditions and populations

that were most easy to address rather than elimination of health disparities among vulnerable

subgroups

(7)

.

Way forward

The changing trends in population demographics and the global disease burden will impact

maternal risk and inuence the strategies that countries implement to end preventable mater-

nal deaths.

The “obstetric transition” concept was adapted from classic models of epidemiologic transitions

experienced as countries progress along a trajectory towards development. Applied to mater-

nal and newborn health care, countries pass through a series of stages that reect health system

status and the shift in primary causes of death as reductions in the rate of maternal mortal-

ity are achieved. In theory, as development progresses, bringing declines in fertility and overall

maternal mortality, the causes of death shift from direct causes and communicable diseases to

a greater proportion of deaths from indirect causes and chronic diseases

(3)

. In practice, this

shift is observable in recent estimates of global maternal causes of death

(8)

. Dierent primary

causes of death require dierent strategies and interventions. The stages described in the obstet-

ric transition model can provide guidance on the most urgent health priorities and focal areas

for improvement at various levels of MMR. Improved understanding of the causes of death in

each context through maternal death surveillance and response (MDSR), condential enquires,

and other methods for counting every death will provide more information to plan targeted

interventions.

An important corollary to this model is the need for dynamic planning that both accounts for

immediate priorities and projects future needs as countries move toward EPMM. Countries

with very high MMR would need to focus strategies on family planning, tackling direct causes

5

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

of maternal mortality, and improving basic social and health system infrastructure and mini-

mum quality of care. Countries with lower MMR face a dierent set of primary risks and health

system challenges; their strategies must shift to address noncommunicable diseases and other

indirect causes, social determinants of poor health, humanization of care, and the over-use of

interventions. Countries in the middle MMR ranges face simultaneous challenges of infectious

and noncommunicable conditions that have an impact on maternal health and survival. While

equity is an important concern at all levels, as average mortality rates fall, special attention must

be laid on eliminating disparities among vulnerable subgroups.

Therefore, EPMM must have a framework that is specic to oer real guidance for strategic plan-

ning by policy makers and programme planners, yet exible to be meaningfully interpreted and

adapted for maximal eectiveness in the various country contexts in which it must be imple-

mented. An intensive consultative process has informed the development of EPMM targets and

strategies to fulll this objective (see Annex 1).

Box 1: Population dynamics

Changing demographics will have signicant implications for programme planning and ser-

vice delivery in the decades to come. The population inux into cities and increased number

of people living in urban slums may well change how people demand and access health

services. Increase in people around the world moving to cities resulted in 55 million new

slum dwellers globally since 2000. These are shifting needs that pose a challenge for coun-

try planners and health systems. According to UN Habitat statistics, sub-Saharan Africa has

a slum population of 199.5 million, South Asia 190.7 million, East Asia 189.6 million, Latin

America and the Caribbean 110.7 million, Southeast Asia 88.9 million, West Asia 35 million

and North Africa 11.8 million

(9)

.

Factors such as rapid urbanization, political unrest in conict areas, changes in fertility rates,

or growing numbers of institutional births change the panorama of maternal risk and call for

reappraisal of a country’s maternal health strategy and programme priorities. Privatization

and decentralization of health care delivery systems are responses to changing population

dynamics whose eects must be studied

(10)

. Countries need tools to identify current pro-

gramme priorities based on the most frequent direct causes and determinants of maternal

death in their context. Immediate, medium term and long range planning are needed to

project health system infrastructure, commodities and maternity care workforce that can

meet these evolving needs, along with a rational framework for their allocation. A single

maternal health strategy will not be adequate for every country, or within each country over

time and for all subpopulations.

6

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Targets for maternal mortality

reduction post-2015

Maternal health stakeholders strongly support the continued need for a specic target for mater-

nal mortality reduction in the post-2015 development framework, with the ultimate goal of

ending all preventable maternal deaths. To achieve this goal, progress needs to be accelerated

as well as concerted national/global eorts and global targets are needed to reduce disparities

in maternal mortality between countries. Within countries, national targets and plans must also

address disparities among subgroups to help achieve both national and global equity, and a

“grand convergence” in maternal survival.

Global targets to increase equity in global MMR reduction

By 2030,

all

countries should reduce MMR by at least two thirds of their 2010 baseline level. The

average global target is an MMR of less than 70/100 000 live births by 2030. The supplemen-

tary national target is that

no

country should have an MMR greater than 140/100 000 live births

(a number twice the global target) by 2030.

Achieving the above post-2015 global target will require an average global ARR in MMR of 5.5%,

similar to the current MDG 5a target. To achieve the global target all countries must contrib-

ute to the global average by reducing their own MMR from the estimated 2010 levels (based on

forthcoming maternal mortality estimates 1990–2015 developed by the Maternal Mortality Esti-

mation Inter-Agency Group (MMEIG)).

Intensied action is called for in countries with the highest MMRs who will need to reduce their

MMR at an ARR that is steeper than 5.5%. However, the secondary target is an important mech-

anism for reducing extremes of between-country inequity in global maternal survival. Countries

with the lowest MMRs nd it dicult to achieve a two third reduction from the baseline. It is rec-

ognized that when the absolute number of maternal deaths is very small, dierences become

statistically meaningless, hampering comparisons. However, even in these countries, there are

likely to be subpopulations with high risk of maternal death, and thus achieving within-country

equity in maternal survival would be an important goal.

These targets while ambitious are feasible given the evidence of progress achieved over the past

20 years. They will focus attention on maternal mortality reduction and maternal and newborn

health as critical components of the post-2015 development agenda. The process for setting

these targets and the choice of indicators are articulated elsewhere

(11,12)

.

Country targets to increase equity in global MMR reduction

To prioritize equity at the country level, expanded and improved equity measures should be

developed to accurately track eorts to eliminate disparities in MMR between subpopulations

within all countries.

7

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Country targets: The MMR target of less than 70 by 2030 applies at the global level but not neces-

sarily for individual countries. The following sets of national targets are recommended (Figure 2).

•

For countries with MMR less than 420 in 2010 (the majority of countries worldwide): reduce

the MMR by at least two thirds from the 2010 baseline by 2030.

• For all countries with baseline MMR greater than 420 in 2010: the rate of decline should

be steeper so that in 2030, no country has an MMR greater than 140.

•

For all countries with low baseline MMR in 2010: achieve equity in MMR for vulnerable pop-

ulations at the subnational level.

Target-setting is accompanied by the need for improved measurement approaches and data

quality to allow more accurate tracking of country progress as well as causes of death. To

contextualize the targets and allow collaborative strategic planning and best practice sharing

at the regional level, it may be appropriate, in some regions, to dene more ambitious targets.

Establishment of an interim milestone to track progress toward

the ultimate MMR target

To help countries monitor progress toward individual national targets for 2030 and evaluate the

eectiveness of their chosen mortality reduction strategies, a major interim milestone is pro-

posed for 2020. This will be set based on the nal 2015 MMR estimates, which will determine the

2010 baseline MMR for the post-2015 targets at both the global and national levels.

Country 3

Country 2

Country 1

Global

reduction > 2 ⁄ 3

(ARR ~5.5%)

103

70

50

19

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

1990 2000 20202010 2030

MMR per 100,000 live births

Countries with baseline

MMR <420

ARR: annual rate of reduction.

Source: WHO, 2014b

Country C

Country B

Country A

Global

70

1000

800

600

400

200

0

1990 2000 20202010 2030

MMR per 100,000 live births

Countries with baseline MMR >420

140

FIGURE 2: MMR reduction at country level

8

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Strategic framework for policy

and programme planning to

achieve MMR targets

Laying the foundation for the strategic framework

The contribution of maternal, newborn and child health for sustainable development

EPMM is a pillar of sustainable development, considering the critical role of women in families,

economies, societies, and in the development of future generations and communities. Investing

in maternal and child health will secure substantial social and economic returns. A recent analy-

sis suggests that increasing health expenditure by just US$ 5 per person per year through 2035

in the 74 countries that account for the bulk of maternal and child mortality could yield up to

nine times that value in social and economic benets

(13)

.

Focusing on implementation eectiveness as the foundation for a paradigm shift

A paradigm shift for the next maternal health agenda rests on a strong foundation of imple-

mentation eectiveness, which marries a well-considered strategic policy framework with a

ground-up focus on implementation performance that accounts for contextual factors, health

system dynamics and social determinants of health.

Eective care for women and girls, as well as mothers and newborn must draw upon intersec-

toral collaboration and cooperation at every stage, given the vital linkages between MMR and

a country’s water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) systems, transportation and communication

infrastructure, and educational, legal and nance systems. It must be responsive to local condi-

tions, strengths and barriers, and address implementation needs and challenges from the ground

up. Programme planning must be people-centric, i.e. driven by people’s aspirations, experiences,

choice and perceptions of quality

(14)

. Care services must be based on respect for women’s and

girls’ agency, autonomy, and choice.

Eective programme planning must be wellness-focused and population-based, providing sup-

portive primary and preventive care to the majority of women who are essentially healthy so

that they can experience planned, uncomplicated pregnancies and births, while ensuring that

high risk pregnancies and complications are recognized early, and interventions when indi-

cated are undertaken in an appropriate and timely manner. Care must therefore emphasize the

framework of availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of services (AAAQ), as well as

other human rights standards, such as participation, information and accountability, which are

ensured through cultivation of a robust enabling environment.

Eective service delivery integrates the delivery of key interventions across the sexual, reproduc-

tive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health (SRMNCAH) spectrum whenever possible,

to lower costs while increasing eciencies and reducing duplication of services

(15).

At the same

9

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

time it will meet the health and social needs of women and communities, and support the goal

of people-centric health care. Reproductive and maternal health policy makers and planners

must prioritize adequate resources and eective health care nancing, while ensuring that ser-

vice delivery is cost-ecient.

To be eective for

every

woman, mother and newborn, SRMNCAH care must adopt a rights-based

approach to planning and implementation, situating health care within a broader framework of

equity, transparency and accountability, including mechanisms for participation, monitoring and

redress. Furthermore, improved metrics, measurement systems and data quality are needed to

ensure that all maternal and newborn deaths and stillbirths are counted, and that other impor-

tant processes, structures and outcome indicators of AAAQ are tracked.

Guiding principles, cross-cutting actions and strategic

objectives for policy and programme planning

The following strategic framework reects the contributions and support of a wide stakeholder

base, under which key interventions and measures of success must be developed.

Box 2: Ultimate goal of EPMM

Guiding principles for EPMM

• Empower women, girls and communities.

• Protect and support the mother–baby dyad.

•

Ensure country ownership, leadership and supportive legal, regulatory and nancial frameworks.

• Apply a human rights framework to ensure that high-quality reproductive, maternal and new-

born health care is available, accessible and acceptable to all who need it.

Cross-cutting actions for EPMM

• Improve metrics, measurement systems and data quality to ensure that all maternal and new-

born deaths are counted.

• Allocate adequate resources and eective health care nancing.

Five strategic objectives for EPMM

• Address inequities in access to and quality of sexual, reproductive, maternal and newborn

health care.

• Ensure universal health coverage for comprehensive sexual, reproductive, maternal and new-

born health care.

• Address all causes of maternal mortality, reproductive and maternal morbidities, and related

disabilities.

• Strengthen health systems to respond to the needs and priorities of women and girls.

• Ensure accountability to improve quality of care and equity.

10

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Guiding principles for EPMM

Empower women, girls, families and communities

Prioritizing the survival and health of women and girls requires recognition of their high value

within society through attention to gender equality and empowerment. This includes strategies

to ensure equal access to resources, education (including comprehensive sexuality education),

and information, and focused eorts to eliminate gender-based violence and discrimination,

including disrespect and abuse of women using health care services. Gender-based violence is

widespread around the world and aects the reproductive health of women and girls throughout

their lives. Its adverse consequences include unwanted pregnancies, pregnancy complications

including low birth weight and miscarriage, injury and maternal death, and sexually transmitted

infections, such as human immunodeciency virus infection (HIV)

(16)

.

Strategies for empowering women in the context of their reproductive and maternal health

care must ensure that they not only have the power of decision making but also the availabil-

ity of options that allows them to exercise their choices. Achieving substantive equality calls

for governments to address structural, historical and social determinants of health and gen-

der discrimination, including economic inequality and workplace discrimination, and to ensure

equal outcomes for women and girls

(17,18)

. Evidence shows that when girls exercise their rights

to delay marriage and childbearing and choose to advance in school, maternal mortality goes

down for each additional year of study they complete

(19,20)

. These and other interventions that

develop women’s capacity to care for and choose for themselves contribute to empowerment,

which includes autonomy over their own reproductive lives and health care decisions, access to

health care services and options, and the ability to inuence the quality of services through par-

ticipatory mechanisms and social accountability. Supporting women’s ability and entitlement to

make active decisions also positively inuences the health of their children and families.

People are empowered to participate in and inuence how the health system works when they

are included as true partners in accountability mechanisms, and when participatory processes

are instituted for identifying factors that aect women and girls seeking care. Numerous stud-

ies have also shown that engaging men and boys as supporters and change-agents can improve

the health of families and entire communities

(21)

. In addition to education, information and tra-

ditional or social media campaigns, these critical dimensions of a framework for empowerment,

can help change social norms in families and communities.

Integrate maternal and newborn care, protect and support the

mother–baby relationship

The health outcomes for mothers and their newborn and children are inextricably linked; mater-

nal deaths and morbidities impact newborn and child survival, growth and development

(22)

.

Therefore, an integral part of the framework is to protect and support the mother–baby rela-

tionship and to encourage the integration of strategies and service delivery for both, including

linkage of vital registration data collected for mothers and their newborn and prevention of

mother-to-child transmission of HIV. In eect, any policy or programme that focuses on either

11

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

maternal or newborn health should include consideration of the other. This is the principle of

“survival convergence”

(23)

.

It is important to recognize the special signicance of the mother–baby relationship. Newborn

health outcomes are enhanced when necessary care is provided without separation of the baby

from its mother. Such integration of care is also more acceptable to women and families, and e-

cient for the health system. Maternal and newborn health services should be delivered together

whenever this can be done without compromising quality of care for either.

Prioritize country ownership, leadership and supportive legal,

regulatory and nancial mechanisms

The strategic framework for maternal and newborn health prioritizes country ownership, lead-

ership, and supportive legal, regulatory and nancial frameworks to ensure that strategies for

EPMM transcend policy and translate into action within countries. A key focus of this principle

is good governance and eective stewardship of the full array of political tools, social capital

and nancial resources available to support and enable a high-performing health system. Trans-

parent, publicly available information on maternal health budgets and policies is needed to

promote accountability and deter corruption.

Country ownership applies to leaders and policy makers, and also extends to civil society through

community input and participation. Community engagement and mobilization are enhanced

through social accountability mechanisms that encourage women and communities to partici-

pate in the system and play their part to ensure that maternal and newborn health care is AAAQ,

and is organized to respond to their health needs as well as their values and preferences

(24)

.

Strong leadership encourages an enabling environment to facilitates policies and nancial com-

mitments by country leaders, and also development partners and funders. Strong leadership is

also critical to champion global and country MMR targets, enable all countries to make contin-

uous progress through the stages of the obstetric transition, and develop and maintain health

care systems that can reliably and equitably deliver the necessary care to end preventable mater-

nal deaths.

Supportive legal mechanisms include laws and policies that uphold human rights in the con-

text of maternal health care, laws that guarantee access to comprehensive maternal health care

and provide for universal health coverage (UHC), mechanisms for legal redress for those harmed,

abused or abandoned in the course of seeking care, as well as supportive employment laws and

frameworks for legal licensure of the maternity care workforce within the jurisdictions where

they are needed

(25–28)

. Supportive legal mechanisms also extend beyond the arena of health

care service organization and delivery to include laws that address gender discrimination and

empower women and girls, for example, by prohibiting early marriage.

Supportive regulatory mechanisms enable eective human resources management of the nec-

essary workforce, such as regulation of midwives, nurses and doctors, and guide task sharing

with the goal of increasing timely access to quality care including interventions for prevention

and management of complications. The collection of vital statistics and improved data on causes

of maternal and newborn deaths and stillbirths through MDSR can also be supported through

facilitative regulatory mechanisms.

12

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Supportive nancial mechanisms aimed at achieving UHC include conditional cash transfers,

voucher programmes, various forms of insurance and performance-based incentives. Support-

ive nancial mechanisms can also refer to donor harmonization and eorts by donors to ensure

that funding does not impose structural barriers to the achievement of important outcomes not

readily measured within short funding cycles or along vertical technical and programme lines.

Apply a human rights framework to ensure that high-quality

sexual, reproductive, maternal and newborn health care is

available, accessible and acceptable to all who need it

The Oce of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) supports the various human

rights monitoring mechanisms within the UN system. These treaty-monitoring bodies have con-

sistently viewed maternal mortality as a human rights issue. The Committee on the Elimination

of Discrimination against Woman (CEDAW), the Human Rights Committee and the Committee on

the Rights of the Child have each explicitly interpreted the right to life to include an obligation

to prevent and address maternal mortality

(29–31)

. CEDAW has armed that an important indi-

cator of states’ realization of women’s rights is whether they ensure equality of health results for

women – including lowering of maternal mortality rate

(32)

. Treaty monitoring bodies have also

highlighted the prevention of maternal mortality and the provision of maternal health services

within state obligations to fulll the right to health

(33,34)

. The Committee on Economic, Social

and Cultural Rights has explicitly indicated that states’ obligations to ensure maternal health care

for women – which includes pre-natal and post-natal care – is a core obligation under the right

to health

(35)

. Treaty monitoring bodies have also linked elevated rates of maternal mortality to

lack of comprehensive reproductive health services

(36)

, restrictive abortion laws

(37)

, unsafe or

illegal abortion

(38,39)

, adolescent childbearing

(40)

, child and forced marriage

(41)

and inade-

quate access to contraceptives

(42)

.

The United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) has also recognized high rates of maternal mor-

tality and morbidity as unacceptable and a violation of human rights. Its resolution emphasizes

that maternal mortality is not solely a health and development issue, but also a manifestation of

various forms of discrimination against women

(26)

. International human rights standards require

governments to take steps to “improve child and maternal health, sexual and reproductive health

services, including access to family planning, pre- and post-natal care, emergency obstetric ser-

vices and access to information, as well as to resources necessary to act on that information”.

Where resources are limited, states are expected to prioritize certain key interventions, including

those that will help guarantee maternal health and in particular emergency obstetric care

(43)

.

However, a human rights approach to maternal and newborn health extends beyond the provi-

sion of services to embrace a broader application of rights-based principles aimed at protecting

and supporting the health of populations. The OHCHR in its guidance for addressing maternal

mortality and morbidity using a rights-based approach includes empowerment, participation,

non-discrimination, transparency, sustainability, accountability and international assistance as

fundamental principles. Furthermore, this OHCHR guidance specically highlights enhancing the

status of women, ensuring sexual and reproductive health rights including addressing unsafe

abortion, strengthening health systems and improving monitoring and evaluation as necessary

elements of a rights-based strategic framework for reducing maternal mortality and morbidity

(44)

.

13

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

As it becomes possible to envision an end to preventable maternal and newborn deaths, the

scope of strategic planning must move beyond focusing solely on prevention of worst out-

comes for ‘women at highest risk’ towards supporting and encouraging optimal outcomes

for ‘all women’. Thus, the topmost priorities of a health agenda for a sustainable future must

include educating and empowering women and girls, gender equality, poverty reduction, uni-

versal coverage and access, and equity within the overall context of a rights-based approach to

health and health care. This re-orientation towards optimal health for all requires a fundamen-

tal paradigm shift.

14

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Cross-cutting actions for EPMM

Improve metrics, measurement systems and data quality

A key aim of improving measurement systems is to ensure that all maternal and newborn deaths

are counted. Only an estimated one third of countries have the capacity to count or register

maternal deaths

(45)

. Less than two fths of all countries have a complete civil registration system

with accurate attribution of the cause of death, which is necessary for the accurate measurement

of maternal mortality

(4)

. In 2011, only two of the 49 UN least developed countries had over 50%

coverage of death registration

(46)

.

Today, estimation is necessary to infer MMRs in many countries where little or no data are avail-

able; unfortunately, these countries are the very ones where mortality and severe morbidity are

often highest due to weak health infrastructure. Because countries around the world do not use

standardized instruments and indicators to track maternal mortality, estimation must presently

be used to make international comparisons and measure progress towards global targets. Esti-

mates that are adjusted using models that allow comparability and make up for missing data

yield dierent point estimates than countries’ own data sources, which causes confusion and

consternation.

A cross-cutting priority for the post-2015 strategy is to move towards counting every maternal

and perinatal death through the establishment of eective national registration and vital sta-

tistics systems in every country, as articulated within the recommendations of the Commission

for Information and Accountability

(28)

. This will require implementation of a revised stand-

ard international death certicate that clearly identies deaths in women of reproductive age

and their relationship to pregnancy, and standard birth and perinatal death certicates (still-

births and newborn deaths up to 28 days of age). Ideally, these registries should link the data of

mothers and their newborns. Standard denitions (with standardized numerators and denom-

inators) for coding and reporting maternal deaths and indirect obstetric deaths must be used

both within and across countries for an accurate understanding of the causes of death and to

allow valid comparisons; thus all countries should adopt denitions that are consistent with the

current International Classication of Diseases manual. The World Health Organization (WHO)

has claried the application of these denitions to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and the

puerperium

(47)

. MDSR and similar perinatal death surveillance, including condential inquiries

and collection of quality of care data on near misses and severe morbidities are also important

mechanisms for ensuring that every death is counted.

There are other equally important uses for improved metrics and measurement systems, includ-

ing for the purpose of accountability to track equity and to ensure programme eectiveness.

Indicators for equity that need to be developed should not overburden data collection sys-

tems, specically at facility level. Agreement on programme coverage indicators is needed to

measure quality and eectiveness of care

(48)

; these data could be used also for accountabil-

ity, e.g. through auditing and feedback. In addition to standardized data sources, indicators and

intervals for data collection to allow for better global comparisons, and the local use of data for

ensuring quality of care and health system accountability in clinical programmes are important

15

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

components of programme eectiveness. New technologies for data collection (e.g. mapping,

mobile phones) with shown eectiveness could also speed up data collection to allow eective,

real-time use.

Prioritize adequate resources and eective health care nancing

The imperative to prioritize adequate and sustainable resources for maternal and newborn health

refers both to development partners and donors in the global community, and to political lead-

ers and nancial decision makers in countries. It encompasses adequate budgetary allocation

through specic, transparent budget lines for maternal and newborn health. It includes health

care nancing for UHC as well as innovative nancing mechanisms and incentives to ensure

equity, increase coverage and improve quality. Intersectoral collaboration beyond the health

sector is a critical success factor for EPMM. Close partnership with the nancial sector is a vital

component of intersectoral collaboration, and must include both public and private national

health care players, ministries of nance, and private as well as bilateral global development

partners and donors.

A multistakeholder nancing group led by The World Bank has issued a concept note for a Global

Financing Facility (GFF) for SRMNCAH from 2015 to 2030. Elaborating on analyses published

in two recent reports

(13,49)

, the GFF lays out a framework for achieving the aforementioned

“grand convergence” between low- and high-income countries for these health outcomes by

2030. The framework projects domestic contributions and estimates the gap nancing needed

by donors to achieve high coverage for SRMNCAH by 2030 in the 75 countries in which 98% of

maternal and newborn deaths occur

(50)

. According to this framework, low- and middle-income

countries should allocate at least 3% of their gross domestic product to general government

health expenditures of which at least 25% (and up to 50%) should be allocated to SRMNCAH.

Global funders should make up the funding gap, which is estimated to range from US$ 5.24 per

person in 2015 to US$ 1.23 per person in 2030

(51)

.

Budget transparency, assured through budget monitoring, analysis and advocacy, is an impor-

tant way for civil society beneciaries to verify that policy commitments made are in fact fullled.

A human rights approach to monitoring maternal health budgets ensures that policy deci-

sions, including allocation of nancial resources, are carried out on the basis of transparency,

accountability, non-discrimination and participation

(52)

. The Commission on Information and

Accountability for Women’s and Children’s Health recommends that countries track and report

at least two indicators:

(i) total health expenditure by nancing source, per capita; and

(ii) total reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health expenditure by nancing source, per

capita

(28)

.

Eective health care nancing includes exploration of nancial incentives and other economic

measures for improving AAAQ to women, families and communities. While some nancial incen-

tives have been shown to increase the utilization of maternal and newborn health services and

oer promise in their ability to improve quality and equity, some have had unintended adverse

eects and more studies are needed to ascertain the full impact of nancial incentives on mater-

nal health outcomes

(53)

.

16

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Box 3: Rationale and scope of strategic objectives for EPMM

Progress toward EPMM necessitates a comprehensive approach along the continuum of

care for each pregnancy and throughout each woman’s reproductive years. The approach

should address not only the causes of maternal death, but also the social and economic

determinants of health and survival.

It calls for a system-level shift from maternal and newborn care that is primarily focused on

identication and treatment of pathology for the minority, to skilled and wellness-focused

care for all. This includes preventive and supportive care to: strengthen women’s own capa-

bilities in the context of respectful relationships, be responsive to their needs, focus on

promotion of normal reproductive processes, provide rst-line management of complica-

tions and accessible emergency treatment when needed. This approach requires eective

interdisciplinary teamwork and integration across facility and community settings. Findings

of a new Lancet special series suggest that midwifery is central to this approach

(54)

.

The comprehensive maternal health strategic framework presented here for inclusion in

the post-2015 sustainable development agenda applies across the full continuum of health

care that is relevant to the goal of ending preventable maternal and newborn mortality, and

maximizing the potential of every woman and newborn to enjoy the highest achievable

level of health. This includes sexual, reproductive, maternal and newborn health care, and

comprises adolescent health, family planning and attention to the infectious and chronic

noncommunicable diseases that contribute directly and indirectly to maternal mortality.

Furthermore, the human rights approach that is a fundamental guiding principle of this

strategic framework extends beyond solely the organization and provision of clinical ser-

vices to include focused attention to broader human rights issues that contribute to the

social determinants of health, such as the status of women and gender equality, poverty

reduction, universal coverage and access, as well as non-discrimination and equity.

This strategic framework is intended to provide meaningful and useful guidance to inform

programme planning for EPMM and optimal maternal and newborn health. Given the reality

of nite resources and limited capacities, not every desired intervention can be undertaken

immediately, and some interventions will be more eective than others. Thus, decision

makers have to make rational choices about priorities and phasing, bearing in mind the

human rights principle of progressive realization – the obligation to do everything that is

immediately possible given the constraints of limited resources. The principle of progressive

realization also outlines obligations that are immediate regardless of resources, for example,

the immediate obligation to take action to eliminate discrimination.

The key interventions for EPMM are known; thus the post-2015 maternal health strategy is

not a list of prescribed technical interventions. Countries must now go beyond doing the

right things to do things right. Alongside eective clinical interventions, it is important to

pay attention to the non-clinical aspects of respectful maternity care. The development of

health systems that can deliver the correct interventions both eectively and equitably,

with reliable high quality under conditions that are dynamic is a priority. Moreover, a rm

grounding in implementation eectiveness is important, since programme priorities are

17

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

subject to change as countries move through stages in their transition to lower levels of

maternal mortality.

The strategic framework for EPMM is intentionally non-prescriptive. It oers broad strategic

objectives rather than a detailed list of clinical interventions; interventions and measures

of success must be tailored to the country and selected based upon local context including

epidemiology, geography, health systems capacity and available resources. Each strategic

objective includes illustrative examples of global best practices that need to be adapted,

adopted and monitored to ensure that they are eective in context. Thus, the strategy

emphasizes the importance of short term, medium term and long range programme plan-

ning to achieve and maintain high-performing systems that can deliver improved outcomes.

18

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Elaboration of the ve

strategic objectives to guide

programme planning towards

EPMM

1. Address inequities in access to and quality of sexual,

reproductive, maternal and newborn health care

All countries should increase eorts to reach vulnerable populations with high-quality primary

and emergency SRMNCAH services. Disparities in access to and quality of health care exist wher-

ever there is a factor (such as wealth, geography, gender, ethnicity, class, caste, race, religion) that

places some people at a social disadvantage relative to others and puts them at risk for stigma,

discrimination and unequal treatment. In the context of reproductive, maternal and newborn

health it includes disrespect and abuse of women who seek maternity care in facilities or from

skilled providers. Vulnerable populations include: the urban and rural poor; adolescents; com-

mercial sex workers; people who are marginalized; the socially excluded; lesbian, gay, bisexual,

and transgender population; those living with disabilities or HIV; immigrants; refugees; those

in conict/post-conict areas; as well groups who experience disparities regularly. These dis-

parities must rst be recognized and analysed at a basic level to determine how health system

operations, planning and programming for maternal health, and service distribution result in

inequitable health outcomes so they can be addressed and eliminated.

Governments and technical experts should improve the availability and eective use of data on

inequities and their eect on reproductive and maternal health. Valid equity indicators must be

developed. Disaggregated data on them should be routinely collected and used to understand

the determinants of inequities and to design, implement and monitor interventions to elimi-

nate them.

Programme planners should promote equitable coverage and equal access to sexual, reproduc-

tive, maternal and newborn health care services through better eorts to understand the unique

challenges and needs of subpopulations within societies to achieve substantive equality. This

includes identifying and addressing barriers to access – nancial, legal, gender, age, cultural,

geographic or based on fear of disrespectful care – and understanding the factors, including

values and preferences, that make care acceptable to all who need it and encourage sustained

demand at scale. It also means ensuring that an adequate workforce is available to provide the

full range of SRMNCAH care to all subpopulations. This may include workforce analysis and long

range planning, subsidies to representatives of vulnerable populations for health professional

education, human resources incentives to encourage placement and retention in underserved

communities, and task sharing to extend the reach of essential services.

19

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Health care quality reects the degree to which care systems, services and supplies increase

the likelihood of a positive health outcome

(55)

. Recognizing that inequity in maternal health

includes systematically uneven quality and not just access, eorts must also ensure that the care

that is oered to all populations is of comparably high quality. To this end, governments should

plan, implement and evaluate contextualized policies, programmes and strategies that take into

account inequities and ensure that representatives from disadvantaged groups have a voice in

these processes. This must be part of the eort to understand how to make a global best prac-

tice yield eective, high-quality results in the context in which it is to be implemented and for

all populations.

2. Ensure universal health coverage for comprehensive sexual,

reproductive, maternal and newborn health care

UHC is dened as “all people receiving quality health services that meet their needs without

being exposed to nancial hardship in paying for the services”. This denition encompasses two

equally important dimensions of coverage: reaching all people in the population with essential

health care services, and protecting them from nancial hardship due to the cost of health care

services

(56)

. Particular emphasis must be placed on ensuring access without discrimination,

especially for the poor, vulnerable and marginalized segments of the population

(57)

.

UHC comprises access without discrimination to essential safe, aordable, eective, quality

medicines as well as to essential health services

(57)

. Governments should determine the set

of essential SRMNCAH covered services and commodities, using evidence of cost-eective-

ness to identify the priority package. Strategic planning must include resource mobilization and

eective service delivery to guarantee that the worst-o in the population are reached with the

essential service package, based on an understanding of population demographics and plan-

ning for the appropriate number of human resources.

A priority for expanding coverage to more people is to identify and remove barriers to utiliza-

tion, and to promote the AAAQ. Countries should develop national strategies to improve care

coverage during labour and childbirth, and expand high-quality, evidence-based service cov-

erage to include preconception and interconception care, family planning, antenatal care and

postpartum care. Standards are needed for the indications and safe use of medical and surgical

interventions, including caesarean section. Development of functioning referral systems is cru-

cial. To achieve these goals, governments and development partners should explore innovative

nancing mechanisms to drive improvements in both coverage and quality. Specic provisions

to protect families accessing emergency obstetric care and emergency newborn care from nan-

cial catastrophe are especially important.

Applying a human rights approach to UHC suggests a pathway to progressive universalism.

Reports from WHO and a Lancet Commission have described a pathway to UHC that could be

achieved within one generation. Governments are called upon to rst institute publicly funded

insurance making essential services available to all without out-of-pocket expenditures, and

later to expand services through progressive mandatory prepayment and pooling of funds with

exemptions for the poor, bolstered by a variety of nancing mechanisms, to cover a larger bene-

ts package

(49,56)

. Transparency and participatory mechanisms to include civil society in both

20

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

the decision making process and the monitoring and evaluation of UHC programmes are neces-

sary to maximize ownership and promote accountability.

3. Address all causes of maternal mortality, reproductive and

maternal morbidities and related disabilities

The post-2015 global maternal health strategy cannot prescribe a list of interventions that will

maximize progress towards EPMM in every country. Each country must rst understand the

most important causes of maternal deaths in its population. Programme planning must then

involve prioritization based on analysis of context-specic determinants of risk and health sys-

tems capacity. The stages of a progressive obstetric transition described by Souza and coworkers

provide a framework and suggest programme priorities that may take precedence at each stage

(3)

. This framework cannot be applied indiscriminately but provides a foundation for country-

specic analysis and adaptation based on local ndings. Thus, a clear planning priority is that

countries should improve the quality of certication, registration, notication and review of

causes of maternal death.

While the distribution of major causes of maternal death diers between countries and for sub-

populations within countries, these are well known

(8)

.

At the same time, recent reports support the notion of a transition from deaths attributable to

direct causes where MMR is very high towards a greater proportion of deaths due to indirect

causes as MMR decreases, necessitating an accompanying shift in country strategies for mater-

nal mortality reduction

(8,58)

. Maternal causes of death that carry stigma, including abortion

and HIV infection, are likely to be underreported or misclassied. Nevertheless, recent analyses

suggest that the number of deaths following unsafe abortion has increased signicantly in sub-

Saharan Africa, even as the global number of maternal deaths attributable to complications of

abortion has fallen due to major decreases in developed countries since 1990. Although HIV-

related deaths in pregnancy accounted for 2.6% of global maternal deaths in 2013, they were

associated with nearly 4% of all maternal deaths in sub-Saharan Africa

(4)

.

Unmet need for family planning also contributes substantially to maternal mortality. A recent

analysis using maternal mortality estimates from the WHO and data on contraceptive prevalence

from the 2010 UN World Contraceptive Use database suggested that maternal mortality would

have been almost two times higher in 172 countries without contraceptive use at current levels,

indirect (27%)

haemorrhage (27%)

hypertensive disorders (14%)

sepsis (11%)

abortion complications (8%)

embolism (3%)

other direct (10%)

FIGURE 3: Global estimates for causes of maternal mortality 2003–2009

21

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

and projected that an additional 104 000 deaths per year could be averted by fullling unmet

need for family planning (a 29% annual reduction globally)

(59)

.

Structural and social barriers that contribute to maternal death include delays in seeking, access-

ing and receiving appropriate treatment, as well as health system deciencies that compromise

the availability, accessibility or quality of care.

It is estimated that for every maternal death, 20–30 more women experience acute or chronic

pregnancy-related morbidities, such as obstetric stula or depression, which impair their func-

tioning and quality of life, sometimes permanently

(60)

. The true scope of the problem is unknown

due to lack of accurate systems for measurement. A WHO-led Maternal Morbidity Working Group

has agreed on a consensus denition for maternal morbidity (“any health condition attributed to

or complicating pregnancy, childbirth or following pregnancy that has a negative impact on the

woman’s well-being or functioning”) and is working on the development of a measurement tool

(61)

. Countries must develop plans for tracking and treating maternal morbidities, and should

use standard denitions and metrics whenever possible.

Having identied the most important causes of maternal death, as well as the prevalence of key

diseases and malnutrition along with maternal morbidity, the unmet need for family planning,

the capacity and reach of the health system, and the human and nancial resources available,

each country should plan a context-specic strategy for implementing eective interventions

to address them.

Intersectoral coordination is a critical element of country planning to address all causes of mater-

nal mortality at each stage of the obstetric transition. Where MMR is very high, improvement in

basic infrastructure including WASH systems, roads and health care facilities, workforce planning

and education for girls are key areas for intersectoral linkages with maternal health programme

planning. As countries reduce MMR, there is a need to strengthen the recognition and manage-

ment of indirect causes of maternal death, and coordinate with other relevant sectors and health

providers to address care for noncommunicable diseases, develop innovative education, screen-

ing and management approaches for these conditions, as well as appropriate clinical guidelines

and protocols. Quality and appropriateness of care remain important issues, however with a par-

ticular focus on avoiding over-medicalization and harms related to overuse of interventions

(3)

.

Each strategy should include a systematic approach to implementing evidence-based standards,

guidelines and protocols, and to monitoring and evaluating their outcomes. Countries and devel-

opment partners must agree to collect data on indicators that allow implementers to evaluate

the quality and eectiveness of their care processes. To date, few maternal and neonatal health

programmes in high burden countries have adopted a large-scale process improvement initia-

tive. However, various systematic process improvement methods have shown positive increases

in use of eective interventions

(62)

.

Although eective interventions exist for the major causes of maternal death, in many contexts

the best available, low-cost, high-impact interventions are not implemented well enough or

widely enough. Governments and development partners should make eective interventions

that address the most prevalent causes of death in the population available at scale by building

on existing successful reproductive and maternal health services, taking into account cost- and

programme-eectiveness.

22

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

High-impact evidence-based clinical interventions

Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

(PMNCH)

Essential interventions, commodities and guidelines

for reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health

http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/

publications/201112_essential_interventions/en/

PMNCH publications http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/en/

http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/search/en/

http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/tools/en/

http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/databases/en/

WHO

Guidelines on maternal, reproductive and women’s

health

http://www.who.int/publications/guidelines/

reproductive_health/en/

WHO

Guidelines on preconception care

http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/

documents/concensus_preconception_care/en/

WHO

Reproductive Health Library

http://apps.who.int/rhl/en/

WHO Human Resource Planning (HRP)/Reproductive

Health and Research (RHR)

Clinical and health systems guidance on all aspects of

reproductive health)

www.who.int/hrp/en/

WHO, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), United

Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Averting Maternal

Death and Disability (AMDD) program

Monitoring emergency obstetric care: A handbook

http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/

monitoring/9789241547734/en/

Maternal Health Task Force: PLOS collection on

maternal health

http://www.ploscollections.org/static/maternalhealth

Box 4: Evidence-based resources for planning key interventions

Trustworthy and regularly updated sources for identifying evidence-based, high-impact

clinical interventions, and best available guidance on topics that are critical for eective

health system strengthening are discussed here.

To be eective in the specic context where it is to be implemented, each country’s plan

must be customized to t its own population health needs, health system capacity and

available resources. Moreover, it is likely that the priority interventions for each country will

change over time as the variables in the planning equation shift and as best available evi-

dence on eective clinical interventions evolves.

Therefore, country planners must analyse their context-specic needs, research the best

currently available evidence on eective interventions to meet those needs, and apply a

rational framework for prioritizing essential services and scaling up. Each country’s frame-

work will need to be revisited at regular intervals to track progress, reassess the underlying

assumptions and adjust the plan as needed.

23

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and

Research

Obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive medicine:

Guidelines, reviews, position statements,

recommendations, standards

http://www.gfmer.ch/Guidelines/Obstetrics_

gynecology_guidelines.php

Nutrition

WHO

e-Library of Evidence for Nutrition Actions

http://www.who.int/elena/en/

http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/en/

http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/en/

http://www.who.int/nutrition/gina/en/

http://www.who.int/nutrition/nlis/en/

Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH)

WHO

Water, sanitation, hygiene

http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/

publications/en/

http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/hygiene/en/

http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/hygiene/

settings/ehs_hc/en/

OHCHR

On the right track: good practices in realizing the rights

to water and sanitation

http://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/WaterAndSanitation/

SRWater/Pages/GoodPractices.aspx

Commodities

UN Commission on Life-Saving Commodities for

Women and Children Commissioners’ Report

http://www.unfpa.org/public/home/publications/

pid/12042

Maternity care workforce

WHO

Optimizing health worker roles to improve access

to key maternal and newborn health interventions

through task shifting

http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/

maternal_perinatal_health/978924504843/en/

WHO

Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural

areas through improved retention

http://www.who.int/hrh/retention/guidelines/en/

UNFPA

State of the World’s Midwifery Report 2014

http://unfpa.org/public/home/publications/pid/17601

Global Health Workforce Alliance

Knowledge Centre (multiple publications)

http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/en/

Facility readiness and basic infrastructure

WHO

Service availability and readiness assessment

http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/

sara_introduction/en/

http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/

sara_reference_manual/en/

http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/

sara_implementation_guide/en/

24

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

WHO

Global Health Observatory

Health infrastructure

http://www.who.int/gho/health_technologies/medical_

devices/health care_infrastructure/en/

WHO

Public health and infrastructure

http://www.who.int/trade/distance_learning/gpgh/

gpgh6/en/

WHO

Operations manual for delivery of HIV prevention,

care and treatment at primary health centres in high-

prevalence, resource-constrained settings

http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/imai/operations_manual/en/

Scaling up eective interventions

WHO, Global Health Workforce Alliance

Scaling up, saving lives (report)

http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/

resources/scalingup/en/

WHO-ExpandNet

Beginning with the end in mind: planning pilot

projects and other programmatic research for

successful scaling up

http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/

strategic_approach/9789241502320/en/

K4Health

Guide to fostering change to scale up effective health

services

https://www.k4health.org/toolkits/fostering-change

Institute for Health care Improvement (IHI)

The breakthrough series: IHI’s collaborative model for

achieving breakthrough improvement

http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/

TheBreakthroughSeriesIHIsCollaborativeModelfor

AchievingBreakthroughImprovement.aspx

WHO, UNAIDS, UNICEF

Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS

interventions in the health sector. Progress report 2010

http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/2010progressreport/report/

en/

WHO

Strategic approach to strengthening sexual and

reproductive health

http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/

strategic_approach/RHR_07.7/en/

WHO, ExpandNet

Practical guidance for scaling up health service

innovations

http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/

strategic_approach/9789241598521/en/

WHO, ExpandNet

Scaling up health service delivery: from pilot

innovations to policies and programmes

http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/

strategic_approach/9789241563512/en/

WHO, ExpandNet

Nine steps for developing a scaling-up strategy

http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/

strategic_approach/9789241500319/en/

Health system strengthening

PMNCH

Success factors for women’s and children’s health:

multisector pathways to progress

http://www.who.int/pmnch/successfactors/en/

WHO

Health systems topics: about health systems

HSS publications

http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/en/

http://www.who.int/healthsystems/publications/en/

25

Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM)

Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research

Publications

http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/en/

Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research

A compilation of institutions producing synthesis

documents

http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/synthesis/

alliancehpsr_hpsrsynthesis.pdf?ua=1

Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research

Implementation research platform

http://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/projects/

implementationresearch/en/

4. Strengthen health systems to respond to the needs and

priorities of women and girls

For health systems to respond to the priorities and the needs of women and girls, they must

be seen as social institutions in addition to delivery systems for clinical care interventions, with

the capacity to either marginalize people or enable them to exercise their rights. This complex-

ity reects the conceptualization of health systems as being made up of both “hardware and

software”

(63)

. The “hardware” of a health system represents the basic health system building