What GAO Found

United States Government Accountability Office

Why GAO Did This Study

Highlights

Accountability Integrity Reliability

March 2006

STATE’S CENTRALLY BILLED FOREIGN

AFFAIRS TRAVEL

Internal Control Breakdowns and

Ineffective Oversight Lost Taxpayers

Tens of Millions of Dollars

Highlights of

GAO-06-298, a report to the

Committee on Homeland Security and

Governmental Affairs, U.S. Senate

The relative size of the Department

of State’s (State) travel program

and continuing concerns about

fraud, waste, and abuse in

government travel card programs

led to this request to audit State’s

centrally billed travel accounts.

GAO was asked to evaluate the

effectiveness of internal controls

over (1) the authorization and

justification of premium-class

tickets charged to the centrally

billed account and (2) monitoring

of unused tickets, reconciling

monthly statements, and

maximizing performance rebates.

What GAO Recommends

To improve controls over premium-

class travel, systematically monitor

unused airline tickets, and provide

assurance of accurate and timely

payment of the centrally billed

accounts to maximize rebates,

GAO is making 18

recommendations to State,

including that it

•

develop a management plan

requiring audits of State’s

premium–class travel,

•

modify international travel

management center contracts

to require identification and

processing of unused

electronic tickets,

•

establish procedures to either

pay or dispute transactions on

the Citibank invoice, and

•

urge other users of State’s

centrally billed travel accounts

to comply with existing travel

requirements.

State concurred with all 18

recommendations.

Breakdowns in key internal controls, a weak control environment, and

ineffective oversight of State’s centrally billed travel accounts resulted in

taxpayers paying tens of millions of dollars for unauthorized and improper

premium-class travel and unused airline tickets. State’s over 260 centrally

billed accounts are used by State and other foreign affairs agencies to

purchase transportation services, such as airline and train tickets. GAO

found that between April 2003 and September 2004 State’s centrally billed

accounts were used to purchase over 32,000 premium-class tickets costing

almost $140 million. Premium-class travel—primarily business-class airline

tickets—represented about 19 percent of the tickets issued but about 49

percent of the $286 million spent on airline tickets with State’s centrally

billed account travel cards. GAO determined that this trend continued for

fiscal year 2005. GAO found that 67 percent of this premium-class travel was

not properly authorized, justified, or both. Because premium-class tickets

typically cost substantially more than coach tickets, improper premium-class

travel represents a waste of tax dollars. The examples below illustrate

premium-class travel by senior State executives that was improperly

authorized by annual blanket authorizations. Most of these blanket

premium-class travel authorizations were signed by subordinates who told

us they couldn’t challenge the use of premium-class travel by senior

executives.

Examples of Improper Authorization by Subordinates of Executive Premium-Class Travel

Traveler Grade

Number of premium-

class tickets

Cost of premium-

class-tickets

1 Presidential appointee 45 $213,000

2 Senior Executive Service 26 $104,000

3 Presidential appointee 24 $93,600

Source: GAO.

Ineffective oversight and control breakdowns also contributed to problems

with monitoring unused tickets, reconciling monthly statements, and

maximizing performance rebates. Although federal agencies are authorized

to recover payments made to airlines for tickets that they ordered but did

not use, State failed to do so and paid for about $6 million for airline tickets

that were not used or processed for refund. State was unaware of this

problem before our review because it neither monitored travelers’ adherence

to travel regulations nor systematically identified and processed all unused

tickets. State also failed to reconcile or dispute over $420,000 of

unauthorized charges before paying its monthly bank invoice and instead

deducted the amounts from its bill. Because these amounts were not

properly disputed under the contract terms, State underpaid its monthly bills

and was thus frequently delinquent. Handling questionable charges in this

ad hoc manner sharply reduced State’s eligible rebates. Overall, State

earned only $700,000 out of a possible $2.8 million in rebates that could have

been earned if it had properly disputed unauthorized charges and paid the

bill in accordance with the contract.

www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?GAO-06-298.

To view the full product, including the scope

and methodology, click on the link above.

For more information, contact Gregory Kutz at

(202) 512-7455 or kutzg@gao.gov.

Page i GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

Contents

Letter 1

Results in Brief 3

Background 8

Ineffective Controls over Authorization and Justification of

Premium-Class Travel Led to Wasted Taxpayer Dollars 11

Lack of Oversight and Controls Led to Other Breakdowns 22

Conclusion 28

Recommendations for Executive Action 28

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 31

Appendixes

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 34

Evaluating the Effectiveness of Controls over Premium-Class

Travel 34

Data Reliability Assessment 41

Appendix II: Comments from the Department of State 43

Appendix III: GAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments 53

Tables

Table 1: Examples of Premium-Class Travel Not Authorized or

Properly Justified 16

Table 2: Examples of Waste Related to Unused Tickets 26

Table 3: State and Other Foreign Affairs Agencies’ Premium-Class

Travel Populations Subjected to Sampling 36

Table 4: Premium-Class Statistical Sample Results 38

Figures

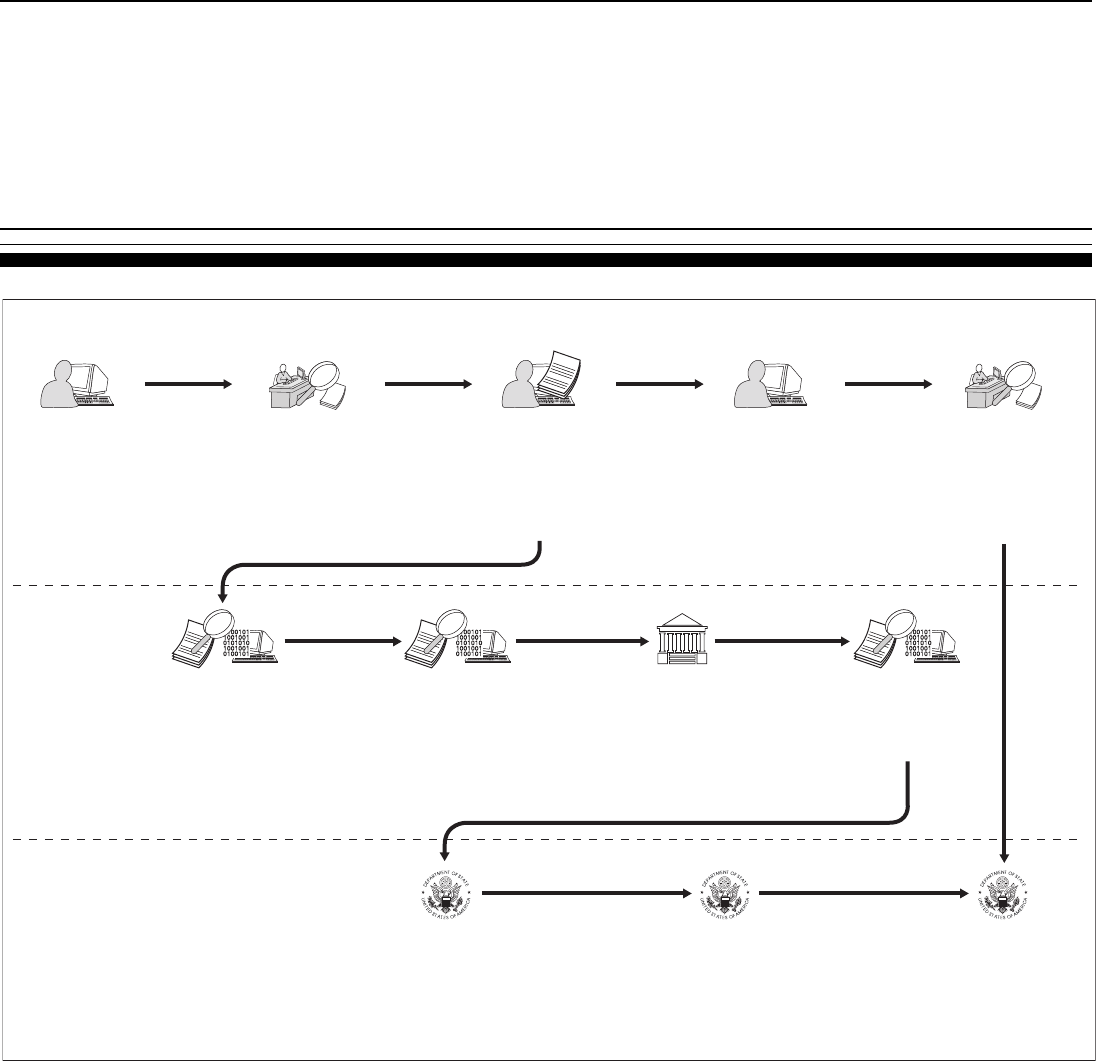

Figure 1: Flowchart of the Centrally Billed Account Travel Card

Process 10

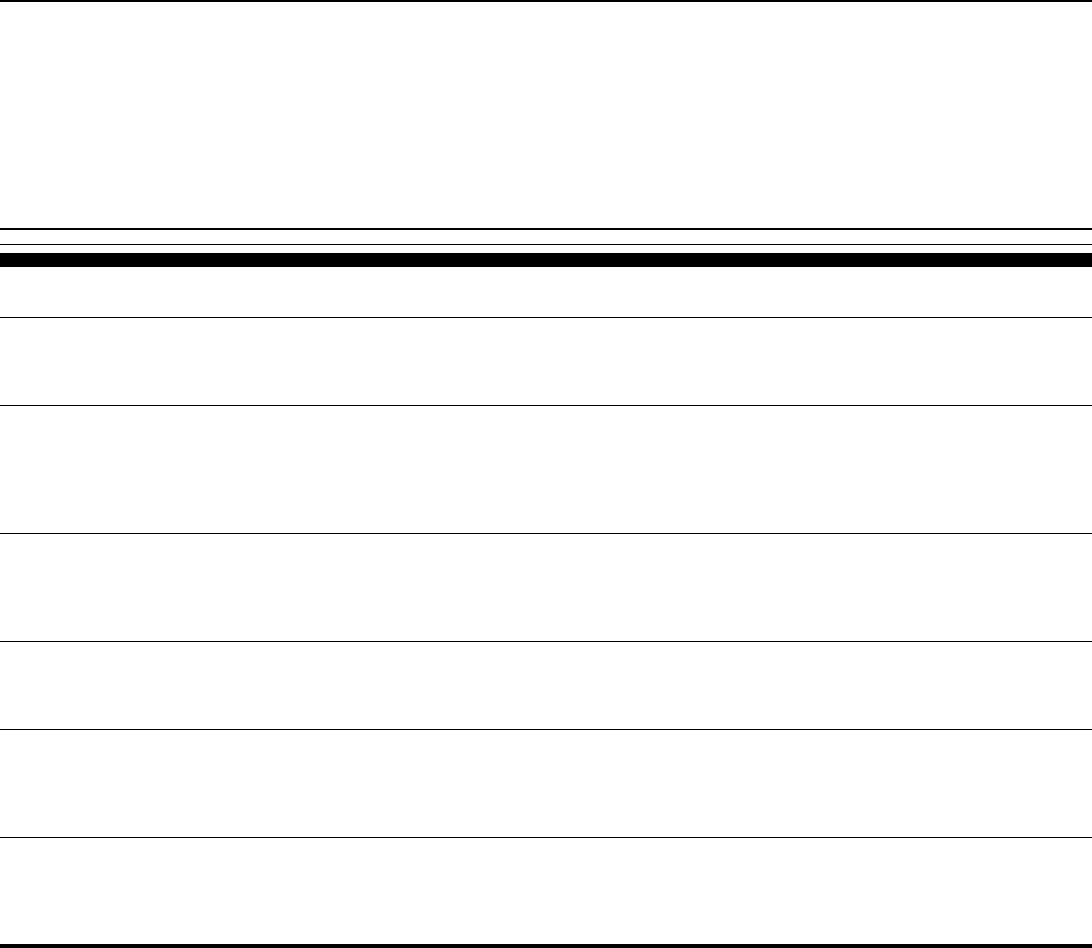

Figure 2: Premium-Class Tickets Purchased for State and Other

Foreign Affairs Personnel Charged to State’s Centrally

Billed Accounts, April 2003 through September 2004 13

Figure 3: Examples of Premium-Class Travel by State and Other

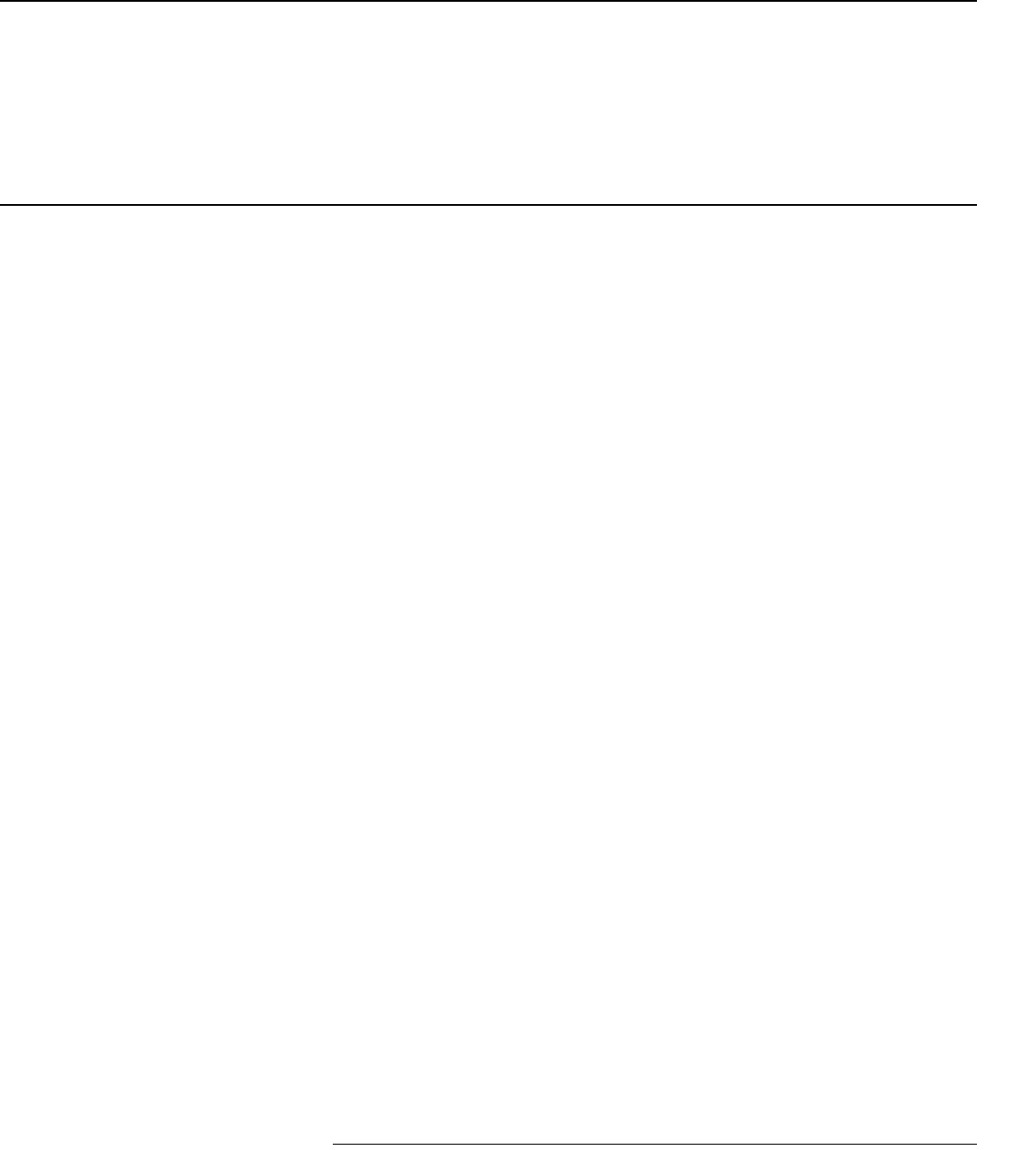

Foreign Affairs Executives from Washington, D.C. 19

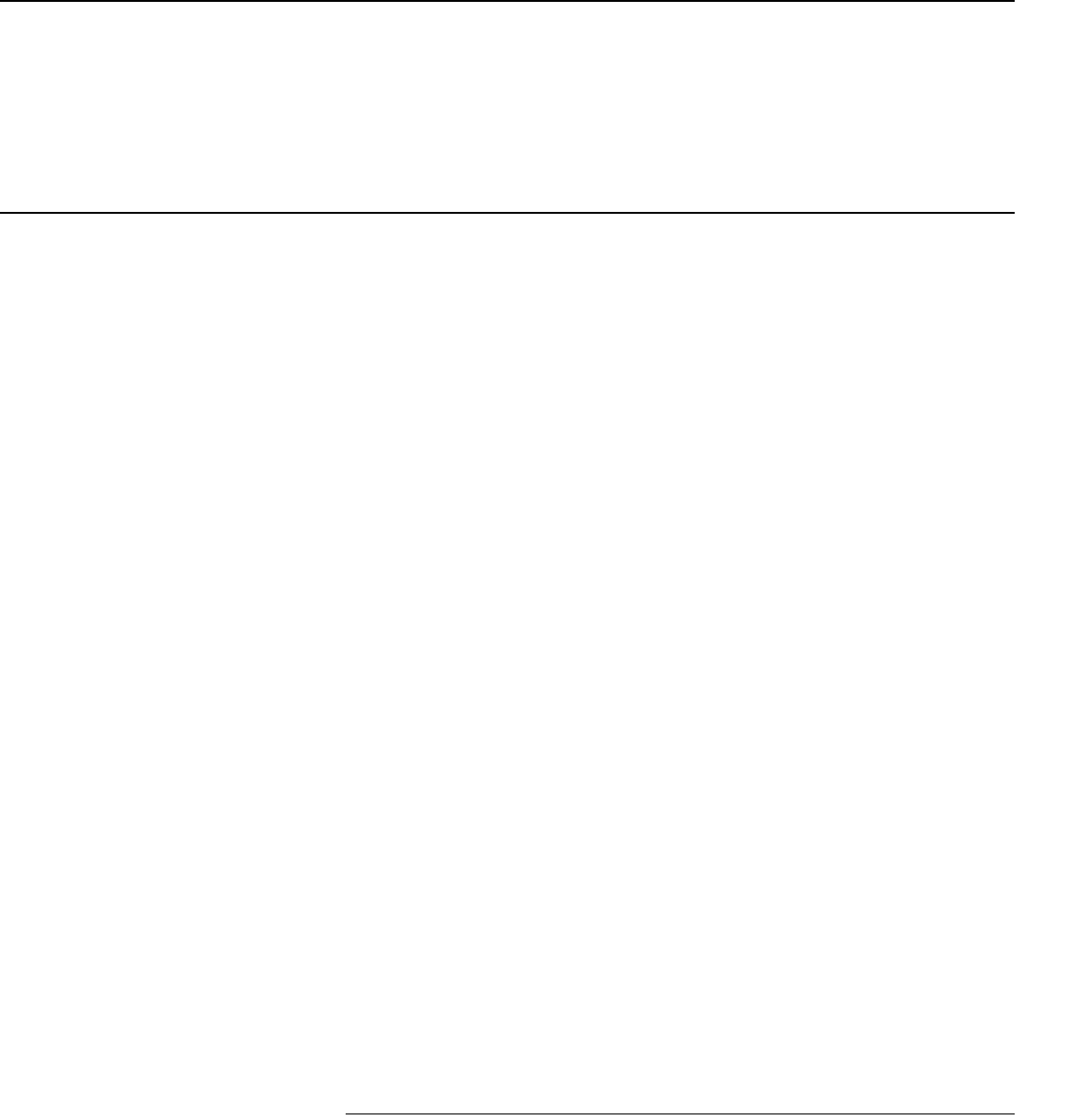

Figure 4: Flowchart of Control Breakdowns in the Unused Ticket

Process 24

Page ii GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. It may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further

permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or

other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to

reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

United States Government Accountability Office

Washington, D.C. 20548

Page 1 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

A

March 10, 2006 Letter

The Honorable Susan M. Collins

Chairman

The Honorable Joseph I. Lieberman

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and

Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

This report responds to your request that we audit controls over the travel

paid for with the Department of State’s (State) over 260 centrally billed

travel accounts, which includes travel related to a number of foreign affairs

agencies (e.g., State and other federal agencies located at United States’

diplomatic missions abroad). State’s centrally billed travel process is used

predominantly by State employees; however, other government travelers

who also use State’s centrally billed accounts reimburse State for their

travel expenses. While State uses purchase orders and Government Travel

Requests (GTR) to pay for some airline tickets at overseas posts, as

requested, our analysis excluded all travel transactions that were not

procured through State’s over 260 centrally billed travel accounts.

1

State leads our government in conducting American diplomacy; its mission

is based on the Secretary of State’s role as the President’s principal foreign

policy adviser. State’s mission is to create a more secure, democratic, and

prosperous world for the benefit of the American people and the

international community. This mission is carried out through six regional

bureaus, each of which is responsible for a specific geographic region of

the world. State operates more than 260 embassies, consulates, and other

posts worldwide and has over 57,000 employees -– including Foreign

Service, civil service, and Foreign Service nationals. Additionally, State’s

posts support other U.S. government agencies, such as the Departments of

Commerce, Defense (DOD), and Homeland Security, which also use State’s

centrally billed accounts when overseas. In general, other agencies

overseas authorize their own travel and State processes the payments

based on their authorizations. In carrying out this mission, State manages

the second largest centrally billed travel card program in the federal

1

State issues individually billed travel card accounts (IBA) to its civil service and foreign

service employees. These accounts are primarily intended to pay for other travel-related

expenses, such as lodging and rental cars.

Page 2 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

government, after DOD. About 70 percent of State’s and other foreign

affairs agencies’ travel is international or at least one flight segment in a

trip had an origin or destination outside the continental United States.

Comparatively, State and other foreign affairs agencies spent more on

premium-class travel than did DOD, both in terms of total dollars spent and

as a percentage of total airline travel.

2

In light of the relative size of State’s

program, and the concerns about fraud, waste, and abuse in government

travel card programs, you requested that we audit premium-class travel and

other centrally billed travel account activities. Federal travel regulations

define premium-class travel as any class of accommodation above coach

class, that is, first or business class.

The centrally billed travel accounts are used by State bureaus, overseas

posts, and other foreign affairs agencies to purchase transportation

services such as airline and train tickets, while the individually billed

accounts are used by individual travelers for lodging, rental cars, and other

travel expenses. For fiscal years 2003 and 2004, State incurred over

$400 million in expenses on its centrally billed and individually billed travel

accounts, with over $360 million charged to its centrally billed accounts.

Because State disburses funds directly to Citibank under a

governmentwide travel card contract for charges made to the centrally

billed accounts, the use of these accounts for improper

3

transportation,

especially the use of the more expensive premium-class travel, results in

direct increased cost to the government. Governmentwide, General

Services Administration’s (GSA) Federal Travel Regulation, and sections

of the U.S. Department of State’s Foreign Affairs Handbook (FAH) and the

U.S. Department of State’s Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM), require that

travelers use coach-class accommodations for official domestic and

international air travel, except when a traveler is specifically authorized to

2

Recognizing that DOD and State have different missions, DOD’s premium-class travel

represented 1 percent of total DOD airline transactions and 5 percent of total dollars spent

on airline travel charged to the centrally billed accounts for fiscal years 2001 and 2002.

3

For this report, we define improper premium-class transactions as those for which

travelers did not have specific authorization to use premium-class accommodations or those

transactions that were properly authorized but did not provide specific justification for

premium-class travel that was consistent with State regulation or policy. We also considered

transactions improper if premium-class travel was authorized under State policies or

procedures that were inconsistent with the Federal Travel Regulation or the guidance

provided in our Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government (GAO/AIMD-00-

21.3.1) and our Guide for Evaluating and Testing Controls Over Sensitive Payments

(GAO/AFMD-8.1.2).

Page 3 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

use premium class. The travel regulations also state that travelers on

official government travel must exercise the same standard of care in

incurring expenses that a prudent person would exercise when traveling on

personal business.

As you requested, the objective of our audit was to determine the

effectiveness of State’s internal controls over its centrally billed travel card

program and determine whether fraudulent, improper, and abusive travel

expenses exist. Specifically, we evaluated the effectiveness of internal

controls over (1) the authorization and justification process for premium-

class tickets charged to State’s centrally billed travel accounts and

(2) State’s monitoring of unused tickets, reconciling monthly statements,

and maximizing performance rebates.

To meet our objectives, we (1) reviewed applicable laws, regulations, and

practices governing travel, including the use of centrally billed travel

accounts; (2) interviewed State officials on its travel policy and procedures,

including the use of centrally billed travel and under what circumstances

premium-class travel is authorized; (3) extracted premium-class and other

transactions from Citibank databases of charges made to State’s centrally

billed accounts for fiscal years 2003 and 2004; (4) tested a statistical sample

of premium-class transactions, 5) used data mining to identify additional

instances of improper premium-class travel based on the frequency and

dollar amount of premium-class travel, including premium-class travel by

senior executives; (6) compared data on unused tickets provided by

airlines to data provided by Citibank; and (7) conducted other audit work,

including visits to two overseas locations to evaluate the design and

implementation of key control procedures and activities. We performed our

audit work from September 2004 through November 2005 in accordance

with U.S. generally accepted government auditing standards. We performed

our investigative work in accordance with standards prescribed by the

President’s Council on Integrity and Efficiency. A detailed discussion of our

scope and methodology is presented in appendix I.

Results in Brief

Breakdowns in key internal controls, a weak control environment, and

ineffective oversight of State’s centrally billed travel accounts resulted in

taxpayers paying tens of millions of dollars annually for unauthorized and

Page 4 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

improper premium-class travel and unused airline tickets.

4

Additionally,

State failed to properly reconcile or dispute over $420,000 in unauthorized

charges, which in addition to raising concerns about potential fraud,

resulted in State failing to earn over $2 million in rebates intended to

reduce the cost of government travel. These problems occurred because

State (1) did not have management controls in place to effectively oversee

and monitor its centrally billed accounts and the extent of premium-class

travel and (2) treats premium-class travel accommodations as a benefit for

working for the department.

We determined that breakdowns in key controls led to an estimated

67 percent

5

of premium-class travel by State and other foreign affairs

personnel during most of fiscal years 2003 and 2004 not being properly

authorized or justified. Because a premium-class ticket frequently costs

two to three times the amount of a coach ticket, taxpayers paid tens of

millions of dollars for premium-class tickets that were not properly

authorized or justified. For example, our statistical sample included a

family of four that flew from Washington, D.C., to Moscow for post-

assignment travel. The business-class tickets cost $6,712 ($1,678 each) and

the flight lasted about 12 hours, which does not meet the requirements of

the premium-class flight duration. The cost of coach-class tickets—the

form of travel required by travel regulations—would have been $1,784

($446 each), or $4,928 less than the amount actually spent. Further, State

did not have complete and accurate data on the extent of premium-class

travel and performed little or no monitoring of this travel.

State also made management decisions on premium-class travel that

contributed to increased costs to taxpayers without performing a cost-

benefit analysis. For example, we found that some of State’s top

executives, including some under secretaries and assistant secretaries,

often used premium-class travel regardless of the length of the flight. We

found that State spent over $1 million dollars on premium-class flights for

17 senior executives during most of fiscal years 2003 and 2004. Our analysis

4

Our audit did not specifically question whether travel charged to State’s centrally billed

travel accounts was necessary; however, where State failed to produce evidence supporting

the authorization or justification for the travel, we accurately refer to those travel instances

as potentially fraudulent. Without evidence to the contrary, potential for fraud exists.

5

All percentage estimates from this sample of premium-class transactions have 95 percent

confidence intervals of within plus or minus 10 percentage points of the estimate itself,

unless otherwise noted.

Page 5 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

indicated that most of these flights were domestic or to destinations in

Western Europe or South America and did not last more than the 14 hours

required by federal and state regulations to justify use of premium-class

travel. Further, many of the executives used blanket travel orders signed by

subordinates to justify purchasing premium-class travel. A blanket

authorization is effective for all travel during a certain time period. For

some executives, annual blanket premium-class authorizations were

completed at the beginning of the fiscal year and covered any travel during

that fiscal year. A blanket authorization is not an appropriate vehicle for

authorizing premium-class travel because federal and state travel

regulations require that all premium-class travel be authorized on a trip-by-

trip basis. Also, we continue to consider authorization of premium-class

travel by employees subordinate to the traveler to be a weak internal

control due to both the additional cost and the potential for abuse

associated with premium-class travel. As we have reported in the past,

travel authorized by subordinates is in effect self authorization, which

constitutes a lack of controls over executive premium-class travel.

Senior State officials also told us that the department offered premium-

class travel as a benefit to its other employees for flights lasting over

14 hours, including permanent change of station travel. According to these

officials, this decision was made to improve morale and was arrived at

without performing a cost and benefit analysis. Although federal and State

regulations allow premium-class travel if the flight is over 14 hours without

a rest stop, agencies—such as DOD—attempt to avoid the significant

additional cost associated with these flights by encouraging employees to

take a rest stop en route to their final destination, generally saving

thousands of dollars per trip. As a result of State’s policy, we found

numerous examples in our statistical sample in which State and other

foreign affairs agencies authorized premium-class travel but did not take

into consideration less expensive forms of travel as an alternative.

In addition, we found examples where State’s diplomatic courier service

used premium-class travel under a blanket authorization without specific

justification. Because we did not have authority to open and inspect

diplomatic pouches, we were unable to validate the classification

designations on the packages. Thus, we did not evaluate whether couriers

were necessary or appropriate or if there were any security issues

associated with courier service procedures. However, we believe the

department could potentially save considerable taxpayer dollars if it better

Page 6 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

managed courier use of premium travel. By regulation,

6

State is required to

ensure the secure movement of classified U.S. government documents and

material across international borders.

7

State’s regulations call for

diplomatic couriers to personally accompany classified diplomatic

pouches. State’s practice is to have couriers use premium-class

accommodations to personally escort cargo carried in diplomatic pouches.

Some courier transactions appeared in our statistical sample of premium

travel and data mining of fiscal years 2003 and 2004 transactions and we

found instances among these of premium-class travel that were not

properly authorized, justified, or both. While the courier service used

agency mission requirements to justify premium-class travel by the

couriers, we found courier transactions where premium-class

accommodations were used even when the courier was not escorting

diplomatic pouches and when no other justification for premium-class

accommodations were specified. When couriers are not escorting

diplomatic pouches, they must follow the same travel regulations as all

other State and other foreign affairs employees. We also found that State’s

Courier Service has begun to institute cost-saving measures for couriers

that, if expanded, could save substantial taxpayer dollars. These measures

include the expanded use of cargo carriers (e.g., FedEx), which do not

require the couriers to purchase passenger tickets when they accompany

packages in the cargo area and therefore reduce freight costs.

Ineffective oversight and breakdowns in controls also led to problems with

State’s other centrally billed travel activities. For example, although federal

agencies are entitled to recover payments made to airlines for tickets that

they ordered but did not use, State and other foreign affairs agencies paid

for about $6 million in airline tickets that were not used and not processed

for refund. State officials were unaware of this problem before our audit

because State did not monitor employees’ adherence to travel regulations

and did not have a systematic process in place for travel management

centers to identify and process unused tickets. For example, we found that

State purchased two identical tickets costing over $16,000 for the same

business and first-class travel between Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and

Albuquerque, New Mexico, and one set of tickets valued at over $8,000 was

wasted and never used. State also failed to reconcile or dispute over

6

U.S. Department of State Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM),Vol. 5 and Vol. 12,

implementation of the Omnibus Diplomatic Security and Antiterrorism Act of 1986.

7

This report does not focus on the need for couriers or security issues surrounding their

use.

Page 7 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

$420,000 of unauthorized and potentially fraudulent charges before paying

its travel card account. Instead of disputing these charges with Citibank,

State simply deducted the amounts from its credit card bill. However,

because these amounts were not properly disputed, State underpaid its

monthly bills and was thus frequently delinquent under contract terms. The

unanticipated consequence of these delinquencies was a substantial

reduction in the amount of rebates that State would have been eligible to

receive. Overall, State earned $700,000 out of a possible $2.8 million in

rebates that could have been earned if it had properly disputed

unauthorized charges and paid its bills in accordance with the terms of the

contract.

This report contains 18 recommendations to the Secretary of State aimed at

reducing improper premium-class travel and travel costs related to State’s

centrally billed travel accounts. Our recommendations seek to improve the

internal controls over airline tickets purchased with centrally billed

accounts so that State has reasonable assurance that premium-class travel

is authorized, properly justified, and that because of the additional cost,

minimized to the extent possible. We also recommend that State take a

series of immediate steps to identify and recover all unused and

unrefunded tickets. Further, we recommend that State properly dispute

invalid transactions and pay its centrally billed account on time. Finally, we

recommend that State take actions to achieve efficiencies in the courier

service.

In written comments on a draft of this report, State concurred with all 18 of

our recommendations and stated that it had taken actions or will take

actions to address them. However, in its comments, State said that our

report overstated the amount wasted on premium class travel, and that we

incorrectly implied that State carelessly implemented business class

regulations without adequately considering the increased cost of premium

class travel. We disagree. Our statistical sample clearly demonstrated that a

majority of State’s premium class travel was neither authorized nor

justified. Because premium-class travel is frequently two to three times

more expensive than coach travel, this improper travel resulted in tens of

millions of dollars of wasted taxpayer resources. Further, State could not

provide any evidence that it ever collected or analyzed information about

the costs associated with its premium-class travel practices. In addition,

the travel practices exemplified in this report clearly demonstrate that the

tone set by top State Department executives indicate that it treats

premium-class as an employee benefit regardless of cost and federal law

and regulation.

Page 8 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

Background

State derives its authority to grant leave and travel reimbursements to its

foreign service employees from the Foreign Service Act of 1980. To

implement provisions of the act, the department issued the FAM and the

FAH. Travel by State’s civil service employees is generally governed by the

General Services Administration’s (GSA) Federal Travel Regulation (FTR),

but in some cases is also governed by the FAM. State’s general policy is for

its foreign and civil service employees to travel using coach-class

accommodations provided by common carriers. However, regulations

governing foreign service and civil service travel authorize the use of

premium-class travel under specific circumstances. Both foreign service

and civil service travel regulations require the agency head or his or her

designee to authorize first-class travel in advance. These regulations also

require the authorizing official at a post abroad or the executive director of

the funding bureau or office domestically to authorize premium-class travel

other than first class. Further, in September 2004, the Assistant Secretary of

State for Administration sent a memorandum to all State executive

directors emphasizing “that it is wrong to authorize premium-class travel

on a blanket basis” and “that a separate justification for premium-class

travel is required for each trip.” Federal and State travel regulations

authorize premium-class accommodation when at least one of the

following conditions exists:

• no space is available in coach-class accommodations,

• regularly scheduled flights provide only premium-class

accommodations,

• an employee with a disability or special need requires premium-class

accommodations,

• security issues or exceptional circumstances,

• travel lasts in excess of 14 hours without a rest stop,

• foreign-carrier coach-class air accommodations are inadequate,

• overall cost savings, such as when a premium-class ticket is less

expensive than a coach-class ticket or in consideration of other

economic factors,

Page 9 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

• transportation costs are paid in full through agency acceptance of

payment from a nonfederal source, or

• required because of agency mission (e.g., courier).

The regulations also allow for the traveler to upgrade to premium-class

accommodations, at the traveler’s expense or by using frequent traveler

benefits, but the upgrade cannot be charged to the centrally billed account.

State has the second largest centrally billed travel card program in the

federal government. During fiscal years 2003 and 2004, State used 155

different centrally billed accounts

8

-–143 international and 12 domestic-–to

purchase more than $360 million in transportation services, such as airline

tickets, train tickets, and bus tickets, for State and other foreign affairs

agencies. Each bureau has its own travel budget and is responsible for

obligating its travel expenses. The local travel-authorizing official or the

executive director of the funding office is responsible for determining the

necessity of travel, issuing the travel order, certifying the availability of

funds, and recording an obligation against a unit’s appropriated funds.

State’s travel management centers (TMC) make airline reservations, issue

airline tickets charged to the centrally billed account upon receipt of a

signed travel order, and perform a reconciliation between the tickets it

issued and tickets charged on the Citibank invoice. To complete this

reconciliation process, TMCs are responsible for associating each charge

with a specific travel order. The financial management officer (FMO) at

overseas posts and resource management’s Global Financial Operations in

Charleston, South Carolina, for domestic activity, are generally responsible

for reviewing a TMC’s monthly reconciliation, making appropriate changes,

and certifying or authorizing Citibank’s invoice for payment. Upon receipt

of the TMC’s reconciliation, billed transaction report (BTR), and supporting

files, State pays Citibank for the tickets purchased on the centrally billed

account. State also pays travelers for nontransportation costs claimed on

their individual travel voucher. Figure 1 shows the design of the processes

used to issue an airline ticket on centrally billed accounts and reimburse

travelers for travel expenses. It also explains the roles of different offices in

providing reasonable assurance that airline tickets charged to these cards

are appropriate and meet a valid government need.

8

Although State had over 260 centrally billed accounts during fiscal years 2003 and 2004,

State actively used 155 of the accounts during this same period.

Page 10 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

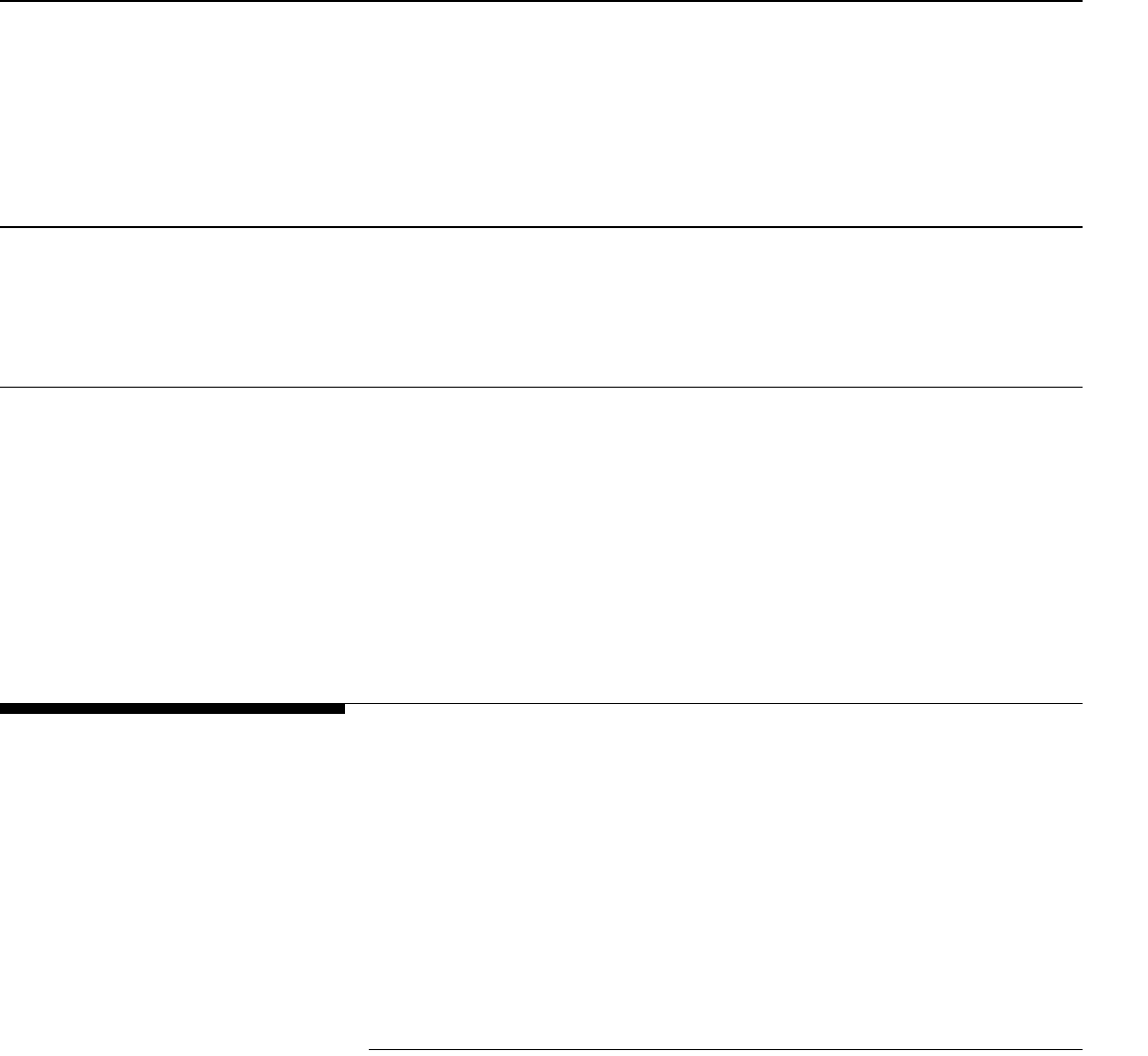

Figure 1: Flowchart of the Centrally Billed Account Travel Card Process

Source: GAO.

Traveler

Traveler makes

reservation and

completes travel

request

Traveler

Traveler completes

travel and claims

reimbursement

Approving

official

Approving Official (A/O)

and financial officer

review travel request

and obligate funds

T.O.

T.O.

T.O.

State

Department

State receives a Billed

Transaction Report (BTR)

and an unresolved transaction

report that includes charges

requiring dispute

State

Department

State reconciles BTR

against obligations (prevalidates

that an obligation exists) and

uploads the information into

State’s accounting system

State

Department

State pays Citibank for

reconciled CBA charges

and pays traveler’s claim

for nontransportation

expenses

Travel Management

Center (TMC)

TMC views TO in Travel

Manager (TM) software

or as paper copy, checks

for approval and funding, and

compares TO origin/destination

and dates to itinerary

Travel Management

Center

TMC charges the centrally

billed account (CBA)

and issues airline ticket to

traveler. TMC maintains

a file of TO with

invoice/itinerary

Travel Management

Center

TMC reconciles CBA

invoice to its own record

of tickets issued

Citibank

Citibank processes CBA

charges, pays the airlines,

and sends the CBA invoice

to the TMC and the State

Department

Approving

official

Approving official(s)

review and approve

travel expenses on

voucher, and submit

voucher for payment

Traveler

Traveler obtains

travel order (TO), and

provides copies to Travel

Management Center

(TMC)

T.O.

Traveler, approving

official

Travel Management

Center, banks

State Department

Page 11 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

Ineffective Controls

over Authorization and

Justification of

Premium-Class Travel

Led to Wasted

Taxpayer Dollars

Premium-class travel accounted for almost half of travel expenditures

charged to State’s over 260 centrally billed accounts during most of fiscal

years 2003 and 2004, including domestic and overseas operations, and this

trend continued for fiscal year 2005. On the basis of our statistical sample,

we estimate that 67 percent of premium-class travel during April 2003

through September 2004 for State and other foreign affairs personnel was

improper--either not properly authorized or properly justified because of

breakdowns in key internal controls. Examples of breakdowns in key

controls include travelers flying premium-class travel when the travel

orders did not authorize premium-class travel; subordinates authorizing

their supervisors to take premium-class flights; and travel orders

authorizing premium-class travel using criteria of a total flight time of more

than 14 hours, even though the actual flight time, including layovers, was

less than 14 hours. Also, State’s diplomatic couriers used premium-class

travel even when it was not justified. In addition, we found that State’s top

executives, including under secretaries and assistant secretaries, often

used premium-class travel regardless of the length of the flight. Further,

senior State officials told us that the department offered premium-class

travel as a benefit to its employees, as part of their human capital initiative,

for all flights lasting over 14 hours, which is allowed by federal and State

regulations but is costly to taxpayers. However, State did not perform a

cost-benefit analysis before offering this benefit. In comparison, agencies—

such as DOD—attempt to avoid the significant additional cost associated

with premium-class travel on flights lasting more than 14 hours by

encouraging employees to take a rest stop en route to their final

destination, saving hundreds, sometimes thousands, of tax dollars per trip.

Prior to 2002, State policy prohibited the use of premium-class

accommodations for permanent change of station travel even when the

duration of the travel exceeded 14 hours—a prohibition established by

many other agencies with staff stationed overseas. However in 2002, State

eliminated that prohibition.

Extent of Premium-Class

Travel Is Significant

Between April 2003 and September 2004,

9

State and other foreign affairs

agencies purchased over 32,000 airline tickets costing about $140 million

that contained at least one leg of premium-class travel for State and other

foreign affairs personnel using State’s centrally billed account travel cards.

9

State’s credit card vendor, Citibank, could not provide the first 6 months of fiscal year 2003

(October 2002–March 2003) data due to limitations in its archiving capabilities.

Page 12 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

In addition, we determined that premium-class travel continues to be

significant for fiscal year 2005.

10

As discussed later in this report, because

State does not obtain or maintain any information on premium-class travel,

it cannot monitor its proper use, identify trends, or determine alternate,

less expensive means of transportation. As shown in figure 2, premium-

class travel represents about 19 percent of the tickets issued, and State’s

and other foreign affairs agencies’ spending on premium-class travel

represented about 49 percent of the $286 million spent on airfare charged

to the centrally billed accounts during the period April 2003 through

September 2004.

11

Our analysis excluded all travel transactions at overseas

posts that were not procured through the centrally billed travel accounts

because it was outside the scope of our request. State told us that at some

overseas posts travelers purchase airline tickets using Government Travel

Requests (GTR) and purchase orders. Further, the information State

provided for some tickets purchased with GTRs did not distinguish

between premium- and coach-class tickets.

10

For fiscal year 2005, on the basis of our analysis of the information available, we

determined that over 17 percent of the tickets issued (17,000 out of 95,000 tickets, ) and over

40 percent of the dollars expended ($80 million out of $196 million) were premium-class

tickets.

11

Figure 2 includes travel related to State, other U.S. government agencies principally

engaged in activities abroad, and other domestic departments and agencies with

international operations. State uses the other foreign affairs agency funds to pay for travel

paid for using State’s centrally billed accounts.

Page 13 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

Figure 2: Premium-Class Tickets Purchased for State and Other Foreign Affairs Personnel Charged to State’s Centrally Billed

Accounts, April 2003 through September 2004

Key Internal Controls over

Premium Travel Were

Ineffective

Breakdowns in key internal control activities led to significant numbers of

transactions lacking proper authorization and justification for premium-

class travel. On the basis of our sample of premium transactions,

12

an

estimated 67 percent of premium-class travel was not properly authorized,

justified, or both. Specifically, 39 percent of the premium-class airline

tickets charged to State’s centrally billed account from April 2003 through

September 2004 were not properly authorized. In addition, 28 percent of

premium-class transactions that were authorized were not justified in

accordance with either federal or State regulations. (See app. I for further

details of our statistical sampling test results.) Further, State did not

maintain accurate and complete data on the extent of premium-class travel

and thus had a lack of controls in place to oversee and manage this travel.

Each fiscal year State is required to report to GSA on first-class travel taken

by all State and other foreign affairs personnel. However, we found

23 roundtrip first-class tickets valued at more than $85,000, obtained for

State or other foreign affairs agencies, that were not reported by State to

19% -

81% -

49% -

51% -

32,000 tickets

Premium class

133,000 tickets

Other class

$140 million

Premium class

$146 million

Other class

Source: GAO analysis of Citibank data.

Percentage of tickets Percentage of dollars

Premium class

Other class

12

Our testing excluded all premium-class transactions costing less than $750 because certain

intra-European flights only offer business-class tickets and therefore are an acceptable

means of airline travel; however, both federal and State regulations require the traveler to

certify this fact on their voucher.

Page 14 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

GSA as required in fiscal years 2003 and 2004. Further, we saw no evidence

of external or internal audits of State’s centrally billed travel program.

13

Proper Authorization Did Not

Exist

Requiring premium-class travel to be properly authorized is the first step in

preventing improper premium-class travel. Federal and State regulations

require premium-class travel to be specifically authorized. State travel

regulations specify that premium-class travel must be authorized in

advance of travel, unless extenuating circumstances or emergencies make

prior authorization impossible, in which case the traveler is required to

request written approval from the appropriate authority as soon as possible

after the travel. Using these regulations, we found that transactions failed

the authorization test in the following two categories: (1) the

documentation did not specifically authorize premium-class travel or a

blanket travel authorization was used to authorize premium-class travel

and (2) the travel order authorizing premium-class travel was not signed.

Premium-class travel was not specifically authorized. On the basis of

our statistical sample, we estimated that the travel orders and other

supporting documentation for 13 percent of the premium-class

transactions did not specifically authorize the traveler to fly premium class,

and thus the travel management center should not have issued the

premium-class ticket. We estimated that an additional 17 percent of the

transactions were authorized by a blanket authorization, including all

diplomatic courier travel. A blanket authorization is not an appropriate

vehicle for authorizing premium-class travel because federal and State

travel regulations require that all premium-class travel be authorized on a

trip-by-trip basis. In September 2004, State issued a memorandum to all

executive directors reminding them about the use of blanket orders,

emphasizing that it is wrong to authorize business-class travel on a blanket

basis and also reminding the executive directors that a trip-specific

justification must be provided for each business-class authorization.

Travel order was not signed. We estimated that 5 percent of premium-

class transactions did not have signed travel authorizations. Ensuring that

travel orders are signed, and signed by an appropriate official, is a key

13

We asked State management if there had been any audits or reviews of the centrally billed

account program, whether internal or external. State officials told us that they did not see

the centrally billed account program as risky and therefore did not conduct reviews of the

program. Further, according to the Assistant Special Agent-In-Charge at State’s Office of

Inspector General (OIG), there had been no travel card investigations during fiscal years

2002, 2003, and 2004.

Page 15 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

control for preventing improper premium-class travel. If the travel order is

not signed, or not signed by the individual designated to do so, State cannot

guarantee that the substantially higher cost of the premium-class tickets

was properly reviewed to ensure it represented an efficient use of

government resources.

Documentation of Valid

Justification for Premium-Class

Travel Often Did Not Exist

Another internal control weakness identified in the statistical sample was

that the justification used for premium-class travel was not provided, not

accurate, or not complete enough to warrant the additional cost to the

government. To determine whether premium-class travel was justified, we

looked at whether there was documented authorization and, if there was,

whether the authorization for premium-class travel was supported by a

valid reason. Thirty-nine percent of premium-class transactions were not

authorized and, therefore, could not have been justified. State asserts that

even if business-class authorization for some trips was not properly

documented, the premium travel was nevertheless justified so long as the

trips were in excess of 14 hours. However, without properly documented

authorization, we cannot assess the propriety of such travel

notwithstanding the 14-hour travel rule and therefore must conclude that it

was unjustified premium-class travel. In addition, 28 percent of premium-

class transactions were authorized but were not supported by valid

justification.

14

Federal and State travel regulations provide that travel in

excess of 14 hours, without a rest stop en route or a rest period on arrival is

justification for premium class. We found premium travel included trips

with such rest stops for flights lasting under 14 hours.

Table 1 contains specific examples of both unauthorized and unjustified

travel from both our statistical sample and data mining work. These

examples illustrate the improper use of premium-class travel and a

resulting increase in travel costs. More detailed information about some of

the cases follows the table.

14

An estimated 51 percent of the transactions would have failed justification regardless of

the authorization status.

Page 16 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

Table 1: Examples of Premium-Class Travel Not Authorized or Properly Justified

Source: GAO analysis of premium-class travel transactions and supporting documentation.

a

Source of estimated coach fares is GSA contract fare or expedia.com.

b

Fares do not include all applicable taxes and airport fees.

• Traveler #1 flew from Washington, D.C., to Honolulu, Hawaii. The total

cost of the trip was $3,228. In comparison, the unrestricted government

fare from Washington, D.C., to Honolulu was $790. According to State

regulation, travelers using premium-class travel are not entitled to an

overnight rest stop en route. Furthermore, the travel was authorized by

a blanket premium-travel authorization signed by a subordinate of the

traveler and a separate trip authorization was not included to

specifically authorize this trip, as required. The travel authorization did

not provide specific justification for business-class travel and the travel

was not more than 14 hours. Therefore, the transaction failed

authorization and justification.

Traveler Source Itinerary

Class of

ticket

Cost of

premium

ticket paid

Estimated

cost of

coach-fare

ticket

a, b

Reason for exception

1 Data mining Washington, D.C., to

Honolulu, Hawaii,

through Canada

Business $3,228 $790 Travel was authorized by a blanket

authorization. Traveler signed their

own upgrade. Continuous travel

without rest stops was less than 14

hours. Transaction failed

authorization and justification.

2 Data mining Johannesburg, South

Africa, to Asmara,

Eritrea, through

Frankfurt, Germany

Business $8,353 $2,921 Traveler approved his own travel.

Traveler flew premium class and was

reimbursed for lodging for a rest stop

en route. Transaction failed

authorization and justification.

3 Data Mining Johannesburg, South

Africa, to Asmara,

Eritrea, through

Frankfurt, Germany

Business $8,353 $2,921 Traveler flew premium class and was

reimbursed for lodging at a rest stop

in Frankfurt. Transaction failed

justification.

4 Data Mining Washington, D.C., to

Honolulu, Hawaii,

through San

Francisco

First class $4,155 $858 Traveler flew first class to Hawaii

using a travel order that allowed for

travel to and within Europe. Travel

was less than 14 hours. Transaction

failed authorization and justification.

5 Statistical

Sample

Washington, D.C., to

Moscow, Russia

Business $6,712 $1,784 Family of four flew business class

from Washington, D.C., to Moscow.

Trip was less than 14 hours.

Transaction failed justification for

premium travel.

Page 17 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

• Travelers #2 and #3 traveled from Johannesburg to Asmara through

Frankfurt, at a cost of about $8,353 each, a total of $16,706. Although

they traveled business class for the entire trip, they were reimbursed for

a hotel room during the layover in Frankfurt on the return visit, at a cost

of about $171 each. According to State regulation, travelers using

premium-class travel are not entitled to a government-funded

15

rest stop

en route. If the travelers had flown coach for this round trip and taken a

rest stop en route, the airfare would have cost about $2,921 and State

could have saved about $11,000 for the two tickets. One of these

travelers approved the travel authorizations for both himself and the

other traveler.

• Traveler #4 flew first class from Washington, D.C., to Hawaii on a

blanket travel order that only authorized travel within Europe. Although

the travel was less than 14 hours, State provided no justification for first

class, and State did not report the first-class travel to GSA. We found

that State issued a first-class airline ticket to Hawaii using a blanket

travel authorization that authorized premium-class accommodations.

State issued the ticket to an unauthorized destination–Hawaii–because

the blanket travel order authorized travel to Europe and State’s travel

officials did not review the blanket authorization to ensure that the

travel authorization was current, valid, and the trip was to an authorized

destination. Because State did not follow its own policies for

authorization and review of travel, the government paid $4,155 for an

unauthorized trip.

Management Decisions to

Offer Premium Travel as a

Benefit

State’s management allowed top State and other foreign affairs executives

to use premium-class travel by approving blanket travel orders, similar to a

blank check. State also allowed premium-class travel as a benefit–without

considering less expensive alternatives–to other employees for flights

lasting over 14 hours and for permanent change of station travel, costing

taxpayers tens of millions of dollars. Further, State’s practice is for

diplomatic couriers to use premium-class travel accommodations to escort

diplomatic pouches.

15

Although the rest stop was not overnight, the travelers arrived in Frankfurt early in the

day and obtained lodging at government expense to rest while waiting for an evening flight

from Frankfurt to Johannesburg.

Page 18 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

Executive Premium-Class

Travelers

State’s top executives, including under secretaries and assistant

secretaries, often used premium-class travel regardless of the length of the

flight. Our data mining of frequent premium-class travelers showed that

many of these travelers were senior foreign affairs executives. On the basis

of this information, we expanded our data mining to include trips taken by

selected presidential appointees and SES-level foreign affairs staff to

determine if their travel was authorized and justified according to federal

and State regulations. In addition to the federal and State regulations, we

also applied the criteria set forth in our internal control standards

16

and

sensitive payments guidelines

17

in evaluating the proper authorization of

premium-class travel. For example, State travel regulations and policies do

not restrict subordinates from authorizing their supervisors’ premium-class

travel, a practice which our internal control standards consider to be

flawed. Therefore, a premium-class transaction that was approved by a

subordinate would fail the control test based on our internal control

standards. State and other foreign affairs agencies paid over $1 million for

269 premium-class tickets for flights taken by 17 foreign affairs executives

during April 2003 through September 2004. We found 65 tickets containing

business- and first-class segments costing about $300,000 that were under

14 hours. Most of these flights were to destinations within the United

States, South America, and Western Europe. Further, over $860,000 in

premium-class trips taken by executives were obtained using blanket

authorizations. For each premium-class trip, State regulation requires

specific authorization to fly premium class. In most cases, the blanket

travel orders authorized premium-class travel for an entire year and were

signed by subordinates. State officials told us that because the blanket

authorization allowed premium class, the executives obtained premium-

class tickets even when the trip was under 14 hours. The subordinate

authorizers told us they could not challenge an under secretary or an

assistant secretary. Examples of premium-class trips associated with

improper accommodation and their additional cost to taxpayers are

included in figure 3 to illustrate the issues associated with executive

premium-class travel found through our data mining.

16

GAO/AIMD-00-21.3.1.

17

GAO/AFMD-8.1.2.

Page 19 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

Figure 3: Examples of Premium-Class Travel by State and Other Foreign Affairs

Executives from Washington, D.C.

Note: GSA fares exclude applicable taxes and fees.

Other Premium-Class Travelers

State also made a management decision to offer premium-class travel to its

employees as a benefit, resulting in increased costs to taxpayers. Although

State officials were aware that offering employees rest stops on longer

flights was often less expensive than premium-class travel, they offered the

more expensive premium-class travel to employees for all flights lasting

over 14 hours, which increased costs. For example, one individual in our

statistical sample flew premium-class roundtrip from Washington, D.C., to

Tel Aviv at a cost of over $6,000. Although the trip lasted over 14 hours, as

an alternative to paying the premium-class rates, State could have flown

this employee coach and paid the cost of an overnight rest stop in London,

for a total cost of about $2,300 (about $1,600 for the GSA contract airfare

and $700 in lodging and per diem expenses). Overall, this option could have

saved taxpayers over $3,700. State officials explained that they made these

decisions about premium-class travel to improve morale and retain highly

qualified foreign-service personnel. State officials also believed that, among

other factors, their decisions about premium-class travel for trips in excess

of 14 hours have led to increased morale, as reflected in “The Best Places to

Work” survey. However, State could not provide any empirical evidence

Source: GAO.

Destination Amount paid GSA fare Potential savings ( = $1,000)

$7,495$780$8,275Zurich, Switzerland

$3,673$800$4,473Manchester, England

$3,308$684$3,992Monterey, California

$4,023$856$4,879Oslo, Norway

$4,826$756$5,582Vienna, Austria

$5,173$1,000$6,173Frankfurt, Germany

$5,178$1,150$6,328Brussels, Belgium

$5,203$630$5,833Amsterdam, Netherlands

$5,301$966$6,267Geneva, Switzerland

$6,565$650$7,215London, England

Page 20 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

that showed a direct correlation that offering premium-class travel

increased its scores on the survey or increased retention of foreign-service

personnel, and could not provide evidence that travel was a metric in the

“Best Places to Work” survey. In contrast, agencies, such as DOD, attempt

to avoid the significant additional cost associated with premium-class

travel on flights lasting more than 14 hours by encouraging employees to

take a rest stop en route to their final destination, saving hundreds,

sometimes thousands, of tax dollars per trip. Finally, our testing showed

that all State employees, not just those in the foreign service that are

governed by State regulations, were authorized to use premium-class,

without constraint, when the trip was over 14 hours.

State also decided to offer premium-class travel to foreign service

employees for permanent change of station moves for all flights that

exceeded 14 hours, in accordance with federal and State regulations.

However, State’s decision resulted in increased costs to taxpayers.

Permanent change of station and similar moves accounted for about

$17 million (12 percent) of State’s and other foreign affairs agencies’

premium-class travel for April 2003 through September 2004. Prior to 2002,

State policy prohibited the use of premium-class accommodations for

permanent change of station travel, even when the duration of the travel

exceeded 14 hours—a prohibition established by many other agencies with

staff stationed overseas, including DOD. However, in 2002, State eliminated

that prohibition at a significant cost to taxpayers. We found numerous

examples in our statistical sample in which premium-class travel was

properly authorized, and as such these transactions were among the 33

percent of transactions that were considered to be properly authorized and

justified. However, it is important to note that because of State’s decision to

treat premium-class travel as a benefit, State did not consider having the

travelers take alternative, less expensive forms of travel.

Premium-Class Travel by

Diplomatic Couriers

We found instances where State’s diplomatic couriers

18

lacked proper

18

authorization, justification, or both when flying premium class; therefore,

we believe State could potentially save considerable taxpayer dollars if it

more aggressively managed the travel of its couriers. For example, when

couriers are not on a mission to escort diplomatic pouches or they are

escorting only cabin-carried diplomatic pouches, they must follow the

18

As mentioned, we did not evaluate whether couriers were necessary or appropriate or if

there were any security issues associated with courier service procedures.

Page 21 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

same travel regulations explained earlier as all State and other foreign

affairs employees.

19

We tested diplomatic courier transactions in our statistical sample of

premium-class transactions and performed data mining of fiscal year 2003

and 2004 transactions. In total, we tested over 20 diplomatic courier

premium-class transactions. We found control breakdowns similar to those

described above with blanket authorization and justification of courier

premium-class travel. Blanket travel orders were used to authorize

premium-class courier travel for all courier transactions that we tested but,

as stated, blanket orders do not specifically authorize premium travel as

required by State regulations. Although the Courier Service used mission

security requirements to justify premium-class travel by its couriers, we

found examples of premium-class travel when couriers were returning

empty-handed, commonly referred to as “deadheading.” In response to

these findings, Courier Service officials acknowledged that the use of

premium class is not justified when couriers return empty-handed unless

the 14-hour rule applies. Courier Service officials also told us that couriers

may not know when they will be returning empty-handed until they arrive

at an airport and are told that the post did not complete the expected

outgoing pouch. By that time, they may not be able to downgrade their

return ticket to economy class because a foreign airline is unwilling to do

so, or time does not permit them to return to the gate to change their ticket.

However, the Courier Service did not indicate on the documentation that it

provided to us any attempts to downgrade their tickets in a deadheading or

any other situation where premium-class travel was not justified. Further,

the Courier Service Deputy Director told us that because there are still

some problems in this area, they routinely check courier trip reports to

identify and address any noncompliance.

We found that State’s Courier Service has begun to institute cost-saving

measures that, if expanded, could save taxpayer dollars. These measures

include the expanded use of cargo carriers (e.g., FedEx), which do not

require the couriers to purchase passenger tickets and charge lower freight

costs than the commercial airlines. Our analysis of a FedEx study

19

By regulation, State is required to ensure the secure movement of classified U.S.

government documents and material across international borders. The Courier Service

mission is to provide secure transportation of classified documents and materials for the

federal government. State’s practice is for its diplomatic couriers to use premium-class

travel accommodations to personally escort diplomatic pouches containing classified U.S.

government documents and material across international borders.

Page 22 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

performed for the Courier Service showed that substantial air cargo

savings and benefits could be achieved through direct cargo flights with

multiple stops along a designated route. Although the Courier Service

initiated the use of cargo carriers in late 2004, expanding this approach to

the extent practical could achieve substantial savings. However, to achieve

the additional savings, the Courier Service would need to overcome foreign

mission resistance to meeting cargo aircraft outside of business hours.

According to Courier Service officials, foreign mission personnel have been

unwilling to meet air cargo shipments that arrive outside normal business

hours and at cargo airports outside city limits. According to State, Mexico

City has recently indicated a willingness to support cargo flight arrivals at

Toluca airport. Courier Service officials also told us that while all agencies

receiving diplomatic pouches should share responsibility for meeting and

taking custody of diplomatic pouch shipments, the burden has generally

fallen on State employees.

Lack of Oversight and

Controls Led to Other

Breakdowns

Ineffective oversight and breakdowns in controls also led to problems with

State’s other centrally billed travel activities. For example, although federal

agencies are entitled to recover payments made to airlines for tickets that

they ordered but did not use, State and other foreign affairs agencies paid

for about $6 million in airline tickets that were not used and not processed

for refund. We found paper and electronic unused tickets for both domestic

and international flights. State was unaware of this problem before our

audit because it did not monitor employees’ adherence to travel regulations

and did not have a systematic process in place for TMCs to identify and

process unused tickets. State also failed to reconcile or dispute over

$420,000 of unauthorized and potentially fraudulent charges before paying

its account. Instead of disputing these charges with Citibank, State simply

deducted the amounts from its credit card bill. This action had the

unanticipated consequence of substantially reducing the amount of rebates

that State would have been eligible to receive. Thus, State earned only

$700,000 out of a possible $2.8 million in rebates that could have been

earned if State disputed unauthorized charges and paid the bill in

accordance with the terms of the contract with Citibank.

Ineffective Controls and

Monitoring Led to

Numerous Unused Tickets

We asked for data on unused tickets purchased on State’s centrally billed

accounts from the top six domestic airlines—United, Continental,

American, Delta, Northwest, and U.S. Airways. All airlines except U.S.

Airways directly provided us electronic data on unused tickets. Data

Page 23 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

provided by the five airlines and verified against Citibank’s data showed

that over 2,700 airline tickets with a face value of about $6 million

purchased with State’s centrally billed accounts were unused and not

refunded. The airline tickets State purchased, for State and other foreign

affairs personnel, through the centrally billed accounts are generally

acquired under the terms of the air transportation services contract that

GSA negotiates with U.S. airlines. Airline tickets purchased under this

contract have no advance purchase requirements, have no minimum or

maximum stay requirements, are fully refundable, and do not incur

penalties for changes or cancellations. Under this contract, federal

agencies are entitled to recover payments made to airlines for tickets that

agencies acquired but did not use.

20

While generally there is a 6-year

statute of limitation on the government’s ability to file an action for

financial damages based on a contractual right,

21

the government also has

up to 10 years to offset future payments for amounts it is owed.

22

State Did Not Monitor Employee

Adherence to Travel Regulations

During fiscal years 2003 and 2004, State did not implement controls to

monitor State’s and other foreign affairs employees’ adherence to travel

regulations requiring notification of TMC or the appropriate State officials

about unused tickets. Federal and State travel regulations require a traveler

who purchased a ticket using the centrally billed account either to return

any unused tickets purchased to the travel management center that

furnished the airline ticket or to turn in unused tickets immediately upon

arrival at their post to the administrative officer or, upon arrival in

Washington, D.C., to the executive officer of the appropriate managing

bureau or office. This notification of an unused ticket initiates a process to

submit requests to the airlines for refunds.

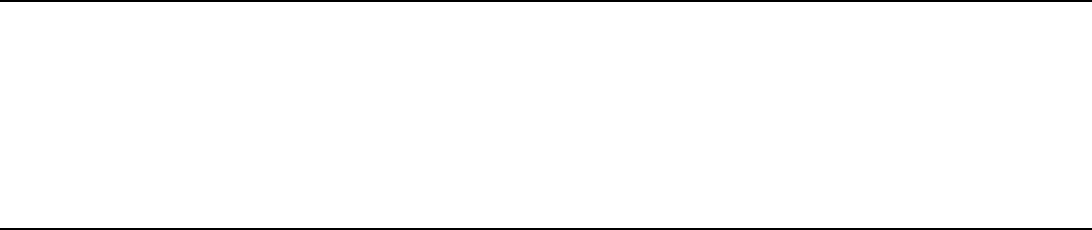

Figure 4 illustrates where control breakdowns can occur if travelers do not

adhere to State requirements. As shown, once a ticket is charged to the

centrally billed account and given to the traveler, State has no systematic

controls to determine independently if the ticket was used—or remains

unused—unless notified by the traveler. If the traveler does not report an

unused ticket, the ticket would not be refunded unless TMC monitored the

status of airline tickets issued electronically and applied for the refunds.

20

31 U.S.C. § 3726(h).

21

28 U.S.C. § 2415(a).

22

31 U.S.C. § 3716(e).

Page 24 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

Figure 4 shows that the failure of the traveler to notify the appropriate

official of an unused paper ticket would result in the ticket being unused

and not refunded. Although bank data indicate that State received some

credits for airline tickets purchased, State did not maintain data in such a

manner as to allow it to identify the extent of unused tickets and to

determine whether credits were received.

Figure 4: Flowchart of Control Breakdowns in the Unused Ticket Process

State Did Not Have a Process for

Travel Management Centers to

Identify All Unused Tickets

State did not have a systematic process in place to monitor whether TMCs

were consistently identifying and filing for refunds on unused tickets. For

instance, State contractually required the domestic TMC to identify and

process all unused electronic tickets. In exchange, the TMC received a fee

for each refund received for an unused ticket. However, State did not

Source: GAO.

Travel Management Center issues

tickets and charges

State Department’s centrally

billed accounts

Ticket is

used or

refunded

Was

ticket fully

used?

Did traveler

notify Travel

Management

Center?

Are unused

tickets

identified?

Is the

ticket

electronic?

Does Travel

Management

Center monitor

unused tickets?

Did Travel

Management

Center request

credit for

unused tickets?

Wasted resources, unused tickets not refunded

Ye s

Ye s No

Ye s

Ye s Ye s

Ye s

No

No

No No No

Page 25 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

implement procedures to determine whether unused tickets were being

identified and credits were being received. Instead, State officials took the

TMC’s monthly report indicating only the total dollar amount of refunds

submitted to the airlines as evidence of contractual compliance. Unless

State implements control procedures to verify whether TMCs were

identifying and filing for refunds on the unused tickets consistently, State

cannot provide reasonable assurance that all requests for refunds resulted

in a credit to the government.

Even when a TMC had procedures in place to identify and process unused

electronic tickets, State was still unable to identify unused paper tickets.

For example, by fiscal years 2003 and 2004, State’s domestic TMC and

TMCs at both of the overseas locations we visited had the capability to

identify or search the databases of the airlines that participate in electronic

ticketing or to receive notification from the airlines of unused tickets, and

subsequently obtain refunds. However, even though the TMCs can identify

electronic tickets, they cannot independently identify paper tickets, which

are typically used for international travel.

23

State has not implemented a

systematic process to verify whether a significant portion of airline tickets

are unused, such as matching tickets issued by TMC with travel vouchers

submitted by travelers upon completion of their trip. Without such a

process State will not have reasonable assurance that tickets purchased

through the centrally billed accounts are used or refunded.

In addition to the $6 million dollars of unused tickets or trip segments we

identified using the airline data, we estimated that, based on the statistical

sample, 3 percent of premium-class airline tickets were unused and not

refunded. This 3 percent estimate is for premium-class tickets only and

excludes coach accommodations.

Table 2 contains specific examples of tickets that the airlines identified as

unused that we tested as a part of our statistical sample of premium class

transactions and data mining selections. Since these tickets were not used,

they resulted in waste and increased costs to taxpayers.

23

We found that about 70 percent of State’s foreign affairs travel is international or includes

at least one flight segment with an origin or destination outside the continental United

States.

Page 26 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

Table 2: Examples of Waste Related to Unused Tickets

Source: GAO analysis.

State Did Not Dispute

Unauthorized Transactions

and Lost Performance

Rebates

State did not dispute over 320 unauthorized transactions, totaling over

$420,000, associated with its two primary domestic centrally billed

accounts during fiscal year 2003 and fiscal year 2004. TMCs reconcile

transactions on the monthly credit card invoice to the tickets issued by the

TMC and recorded in the airline reservation system. Disputes are typically

filed for transactions that neither the TMC nor State identified as having

issued or authorized. Tickets that do not match could occur for many

reasons, such as an airline charging the ticket to the wrong credit card

account, an individual fraudulently obtaining an airline ticket, or the

merchant or credit card vendor failing to provide enough information to

allow the transaction to match. State did not have processes or procedures

in place to file disputes for transactions that failed to reconcile between the

bank invoice and the computer reservation system. We provided State a list

of 219 travelers’ names

24

associated with the over 320 unauthorized

transactions to verify that they were State employees or otherwise

authorized by State or other foreign affairs agencies to travel. According to

State, 38 of the 219 travelers were individuals for whom State had no

record of ever working for State as an employee, contractor, or being

authorized to travel as an invited guest. Thus, these transactions could be

potentially fraudulent charges. As for the remaining 181 travelers, State

informed us that while the airline tickets purchased were for individuals

who are either current or former State employees, contractors, or invited

Traveler Source Itinerary

Class of

ticket(s)

Price paid Explanation for unused tickets

1 Statistical

sample

Albuquerque, NM, to

Ethiopia and return

First and

business

$8,838 Traveler completed travel using a second ticket

issued for the same trip.

2 Statistical

sample

Washington, DC, to

Nigeria

Business $5,503 Traveler went to Senegal instead of Nigeria using a

different ticket.

3 Statistical

sample

Buenos Aires,

Argentina, to Lima,

Peru

Business $1,327 Traveler used an identical coach-class ticket.

4 Data mining Miami, FL, to Mexico Business $2,254 Traveler went to Chile instead of Mexico using a

different ticket.

24

We are investigating these transactions to determine if they are fraudulent.

Page 27 GAO-06-298 State Travel Cards

guests, State has no evidence that the trips had been authorized. Thus,

these trips also could represent potentially fraudulent charges.

As a result of not disputing unauthorized charges and not paying its bill in

accordance with the contract, State faced the unanticipated consequence

of substantially reducing the amount of rebates that it would have been

eligible to receive. For example, if State had effectively managed the

domestic accounts and disputed these charges, State could have earned

over $1 million in rebates. Instead, State earned only about $174,000 in

performance rebates for its domestic accounts. In contrast, at two overseas

posts that we visited, State was properly disputing transactions. However,

as previously noted, State still did not effectively manage its centrally billed

accounts departmentwide and, consequently, earned only $700,000 out of a

possible $2.8 million in performance rebates from Citibank.

The contract that State entered into with Citibank to issue centrally billed