A Position Statement Held on Behalf of the Early Childhood Education Profession

Effective early childhood educators are critical for realizing the

early childhood profession’s vision that each and every young

child, birth through age 8, have equitable access to high-quality

learning and care environments. As such, there is a core body

of knowledge, skills, values, and dispositions early childhood

educators must demonstrate to effectively promote the

development, learning, and well-being of all young children.

Disponible en Español: NAEYC.org/competencias

Professional Standards

and Competencies for

Early Childhood Educators

Adopted by the NAEYC National Governing Board November 2019

Professional Standards and Competencies

for Early Childhood Educators

Copyright © 2020 by the National Association for

the Education of Young Children. All rights reserved.

Permissions

NAEYC accepts requests for limited use of our

copyrighted material. For permission to reprint,

adapt, translate, or otherwise reuse and repurpose

content from the nal published document, review

our guidelines at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions.NAEYC.org

Professional Standards and Competencies

for Early Childhood Educators

3 Introduction

4 Relationship of Five Foundational Position Statements

6 Purpose

6 The Position

7 Design and Structure

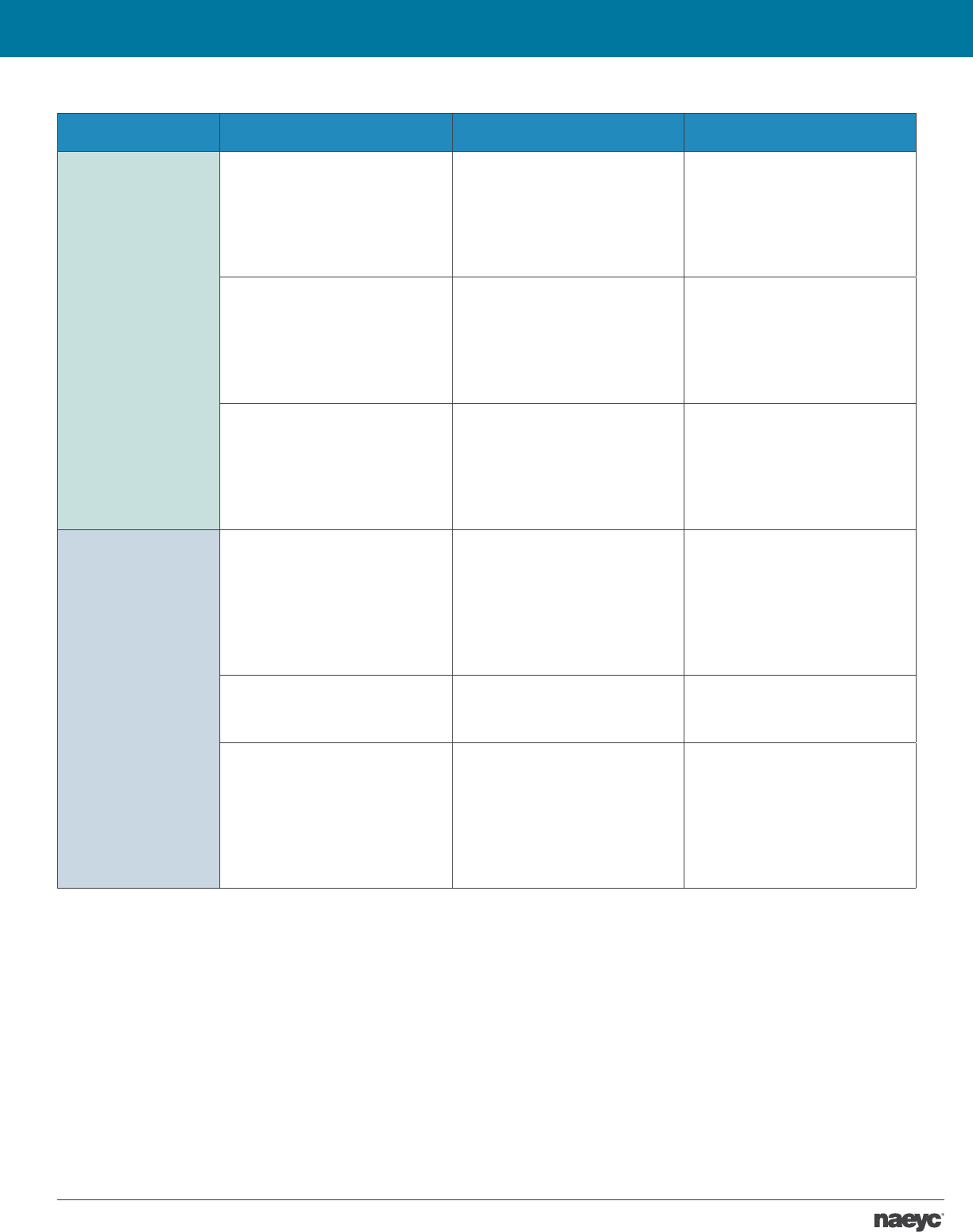

8 Professional Standards and Competencies

9 Summary

11

STANDARD 1: Child Development and Learning in Context

13

STANDARD 2: Family–Teacher Partnerships

and Community Connections

15

STANDARD 3: Child Observation, Documentation, and Assessment

17

STANDARD 4: Developmentally, Culturally, and

Linguistically Appropriate Teaching Practices

20

STANDARD 5: Knowledge, Application, and Integration of

Academic Content in the Early Childhood Curriculum

24

STANDARD 6: Professionalism as an Early Childhood Educator

26 Recommendations for Implementation

26 Early Childhood Educator Professional Preparation Programs

27 Higher Education Accreditation

27 Early Learning Programs

28 Federal, State, and Local Policies

29 Researchers

30 Appendices

30

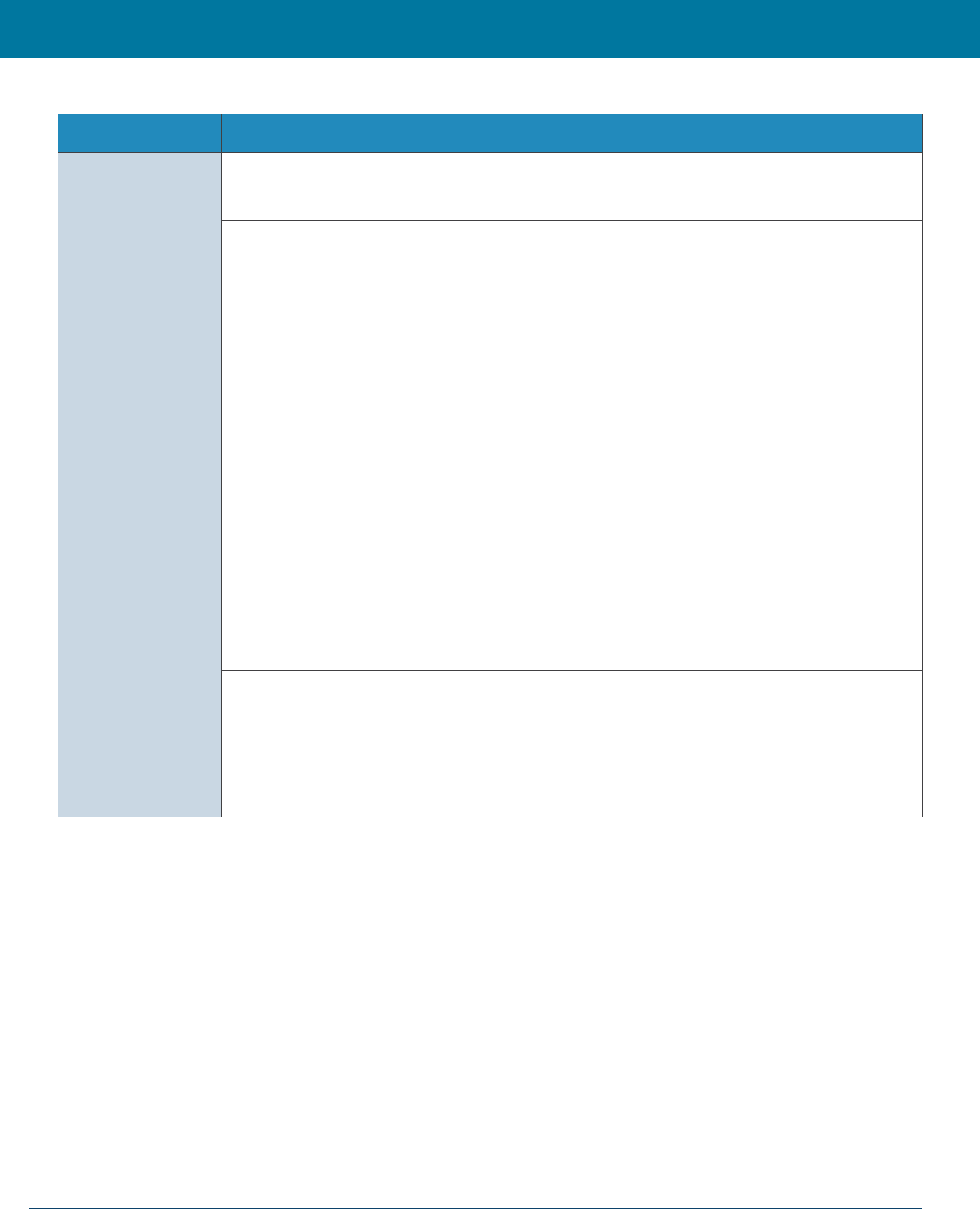

APPENDIX A: Leveling of the Professional Standards

and Competencies by ECE designation

48

APPENDIX B: Critical Issues and Research Informing

the Professional Standards and

Competencies for Early Childhood Educators

51

APPENDIX C: Glossary

58

APPENDIX D: References and Resources

66

APPENDIX E: The History of Standards for Professional Preparation

68

APPENDIX F: Professional Standards and Competencies Workgroup

1 | PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

Developing the Professional Standards and

Competencies for Early Childhood Educators

In 2017, the Power to the Profession Task Force began an extensive process to

review the range of the eld’s existing standards and competencies and establish a

process for arriving at a set of agreed-upon standards and competencies for the early

childhood education profession, working birth through age 8 across states, settings,

and degree levels. This work included a deep look at multiple national standards and

competencies; following a deliberative decision-making process, it resulted in the Task

Force recommendation that the 2010 NAEYC Standards for Initial and Advanced Early

Childhood Professional Preparation Programs be explicitly positioned as the foundation

for the standards and competencies of the unied early childhood education profession.

At the same time, the Task Force set four specic conditions

and expectations for the revision of the NAEYC professional

preparation standards. These included an expectation

that the standards would be reviewed in light of the most

recent science, research, and evidence; it gave particular

consideration to potential missing elements identied in

the Transforming the Workforce report, including teaching

subject-matter specic content, addressing stress and

adversity, fostering socio-emotional development, working

with dual language learners, and integrating technology in

curricula. To revise the standards, and respond to these and

other expectations, including the expectation that the revisions

would occur in the context of an inclusive and collaborative

process, a workgroup was convened in January 2018. The

workgroup comprised the Early Learning Systems Committee

of the NAEYC Governing Board, early childhood practitioners,

researchers, faculty, and subject-matter experts, including

individuals representing organizations whose competency

documents were considered, referenced, and used to inform

the revisions. The organizations included the following

Task Force members: the Council for Exceptional Children,

Division of Early Childhood; the Council for Professional

Recognition; and ZERO TO THREE.

In September 2018, the workgroup released the rst public

draft of the Professional Standards and Competencies for

Early Childhood Educators. This was followed by an extensive

public comment period and months of intensive work to

release the second public draft for needed feedback and

guidance from the eld, higher education, and others. The

second public draft of the competencies, which included a rst

draft of the leveling of the competencies to ECE I, II, and III,

was open from May to July 2019.

The second comment period was followed by extensive

rewriting, supported by a group of experts drawn from

preparation programs at ECE levels I, II, and III. The result

was a third public draft focused solely on the leveling, which

was open from October to November 2019. Ultimately,

the Professional Standards and Competencies for Early

Childhood Educators, leveled and aligned to ECE Levels I,

II, and III, are being released in conjunction with the full

Unifying Framework.

This excerpt is adapted from the Unifying Framework

for the Early Childhood Education Profession.

A POSITION STATEMENT HELD ON BEHALF OF THE EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION PROFESSION | 2

Message from the NAEYC Governing Board

The NAEYC Governing Board is deeply honored to hold the Professional Standards

and Competencies for Early Childhood Educators (“Professional Standards and

Competencies”) on behalf of the early childhood education profession.

In response to the Power to the Profession (P2P) Task

Force’s 2018 decision to name the 2010 NAEYC Standards

for Initial and Advanced Early Childhood Professional

Preparation Programs (a NAEYC position statement) as

the foundation for the standards and competencies for the

unied early childhood education profession, the Governing

Board seriously considered and responded to the attendant

conditions and expectations. The revisions process is outlined

in detail on the opposing page, and we are deeply grateful

to all of the Governing Board members, P2P Task Force

members, early childhood practitioners, researchers, faculty,

state agency personnel, national and state organizations,

and subject-matter experts for their extensive engagement,

feedback, and guidance.

Given that the Professional Standards and Competencies

were developed by and are intended for the early childhood

education eld, and need to be adopted and used by

practitioners, states, professional preparation programs,

employers, and others, NAEYC has updated the name of the

standards. The Governing Board agreed to this because we

believe it is critical for all of us in this profession to own and

use these standards and competencies to guide our work.

While it is the members of the early childhood education

profession who, with support from professional preparation

programs, state systems, and others, are responsible for

implementing the Professional Standards and Competencies,

the NAEYC Governing Board commits to uphold its

responsibilities as the holder of the competencies and its

intellectual property to ensure that the competencies are

faithfully and appropriately utilized and that all future

revisions occur through an inclusive process that engages

the early childhood eld across states and settings.

With gratitude to our profession for doing the hard work

of dening and leveling the core standards and competencies

for all early childhood educators,

Amy O’Leary

President, NAEYC Governing Board

Elisa Huss-Hage

Chair, Early Learning Systems Committee

of the Governing Board

3 | PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

Introduction

This update to the NAEYC Standards for Early Childhood Professional

Preparation responds to the charge from the Power to the Profession (P2P)

Task Force to create nationally agreed-upon professional competencies

(knowledge, understanding, abilities, and skills) for early childhood

educators. As such, it revises the NAEYC 2009 position statement

“Standards for Early Childhood Professional Preparation” and expands

the intent of the standards and competencies to allow their application

across the early childhood eld, including professional preparation

programs, professional development systems, licensure, and professional

evaluations. It places diversity and equity at the center and responds to

the critical competencies identied in Transforming the Workforce for

Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation, the seminal 2015

report by the Institute of Medicine and National Research Council.

This update levels the standards to the scope of practice for each early

childhood educator designation recommended in the Unifying Framework

for Early Childhood Education Profession established by Power to the

Profession: ECE I, ECE II, and ECE III. For clarity, see Appendix A, “Leveling

of the Professional Standards and Competencies.” This document

also lays out recommendations for implementation of the standards

for multiple stakeholders in the early childhood education eld.

Details about the context in which the updated standards were developed and the history

of NAEYC’s professional preparation standards can be found in Appendices B and E.

A POSITION STATEMENT HELD ON BEHALF OF THE EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION PROFESSION | 4

Relationship of Five Foundational Position Statements

This position statement is one of ve foundational documents

NAEYC has developed in collaboration with the early childhood

education eld. While its specic focus is on dening the core

standards and competencies for early childhood educators,

this statement complements and reinforces the other four

foundational documents, which do the following:

› Dene Developmentally Appropriate Practice

› Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education

› Dene the profession’s Code of Ethical Conduct

› Outline Standards for Early Learning Programs

Developmentally

Appropriate

Practice (DAP)

Professional

Standards and

Competencies for

Early Childhood

Educators

Code of

Ethical Conduct

Advancing

Equity in Early

Childhood

Education

NAEYC

Early

Childhood

Program

Standards

NAEYC’s Foundational Documents

5 | PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

The early childhood educator professional preparation

standards herein are aligned with the ve broad categories

of educators’ decision-making described in depth in the

developmentally appropriate practice position statement:

› Using knowledge of child development

and learning in context to create a caring

community of learners (Standard 1)

› Engaging in reciprocal partnerships with families and

fostering community connections (Standard 2)

› Observing, documenting, and assessing children’s

development and learning (Standard 3)

› Teaching to enhance each child’s development

and learning (Standard 4)

› Understanding and using content areas to plan

and implement an engaging curriculum designed

to meet goals that are important and meaningful

for children, families, and the community in the

present as well as the future (Standard 5)

The key elements of Standard 6, “Professionalism as an Early

Childhood Educator,” pull forward the knowledge, skills, and

dispositions that early childhood educators need in order

to make decisions that exemplify ethical, intentional, and

reective professional judgment and practice.

Early childhood as an interdisciplinary,

collaborative, and systems-oriented profession

Eective early childhood education and the promotion of

children’s positive development and learning in the early

years call for a strongly interdisciplinary and systems-

oriented approach. By its nature, the early childhood eld

is, and historically has been, interdisciplinary. That is, early

childhood educators need to integrate knowledge of all

aspects of child development—content in academic disciplines,

early intervention programs, and other programs for young

children—and draw on knowledge from other disciplines,

including speech and language therapy, occupational therapy,

special education, bilingual education, family dynamics,

mental health, and multiple other approaches to the

comprehensive well-being of young children and their families.

An interdisciplinary, systems-oriented perspective is essential

if professionals, particularly as they advance in their practice,

are to integrate multiple sources of knowledge into a coherent

approach to their work.

These foundational statements are grounded in NAEYC’s core values, which

emphasize diversity and inclusion and respect the dignity and worth of each

individual. The statements are built upon a growing body of research and

professional knowledge that underscores the complex and critical ways in

which early childhood educators promote early learning through relationships—

with children, families, and colleagues—that are embedded in a broader

societal context of inequities in which implicit and explicit biases are pervasive.

A POSITION STATEMENT HELD ON BEHALF OF THE EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION PROFESSION | 6

Purpose

The position statement presents the essential body of

knowledge, skills, dispositions, and practices required of all

early childhood educators working with children from birth

through age 8, across all early learning settings. It articulates

a vision of sustained excellence for early childhood educators.

The statement has been intentionally developed not only to

guide the preparation and practice of the early childhood

education profession but also to be used by others in the

early childhood eld. It is intended to serve as the core early

childhood educator standards and competencies for the

eld, a document that states can use to develop their own

more-detailed standards and competencies that address

their specic contexts. Ideally, the eld will use this position

statement to align critical professional and policy structures,

including the following:

› State licensing for early childhood educators

› State and national early childhood educator credentials and

related qualication recommendations or requirements

› Curriculum in professional preparation programs

› Articulation agreements between various levels and

types of professional preparation programs

› National accreditation of early childhood

professional preparation programs

› State approval of early childhood educator

professional preparation programs and

professional development training programs

› Expectations for educator competencies in

early learning program settings through job

descriptions and performance evaluation tools

The Position

Eective early childhood educators are critical for realizing

the early childhood profession’s vision that each and every

young child, birth through age 8, have equitable access to

high-quality learning and care environments. As such, there is

a core body of knowledge, skills, values, and dispositions early

childhood educators must demonstrate to eectively promote

the development, learning, and well-being of all young

children. These are captured in the next section, “Professional

Standards and Competencies for Early Childhood Educators.”

These standards will be updated regularly to respond to new

developments in the early childhood eld, new research, and

changing social and policy contexts.

These standards and competencies are informed by

› Research and practice that advance our

understanding of what early childhood

educators need to know and be able to do

› Early childhood standards as well as educator

standards from other professional organizations

› The current context of the early childhood

workforce and higher education

› The imperatives from the Unifying Framework

developed through Power to the Profession

Input from a broad-based workgroup (see Appendix F) and

the early childhood eld underpins the updated standards

and competencies.

7 | PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

Design and Structure

Comprehensive, not exhaustive: These standards and

competencies represent the core domains of knowledge and

practice required of every early childhood educator, and

they provide a baseline of expectations for mastery of these

domains. They are not meant to represent an exhaustive list

of what an early childhood educator should know and be

able to do in order to educate and care for young children.

For preparation programs, certication/licensure bodies,

accrediting bodies, state early childhood career ladders,

educator evaluation systems, and such, the competencies may

be expanded, as needed, to address specic state and local

contexts and to include more discrete competencies.

Aligned with the responsibilities of early childhood

educators: The standards and competencies align with

the early childhood education responsibilities designated by

the Unifying Framework for the Early Childhood Education

Profession (”Unifying Framework”) developed through Power

to the Profession:

› Planning and implementing intentional, developmentally,

culturally, and linguistically appropriate learning

experiences that promote the social and emotional

development, physical development and health,

cognitive development, language and literacy

development, and general learning competencies

of each child served (Standards 4 and 5)

› Establishing and maintaining a safe, caring, inclusive,

and healthy learning environment (Standards 1 and 4)

› Observing, documenting, and assessing children’s

learning and development using guidelines

established by the profession (Standards 3 and 6)

› Developing reciprocal, culturally responsive relationships

with families and communities (Standard 2)

› Advocating for the needs of children

and their families (Standard 6)

› Advancing and advocating for an equitable, diverse, and

eective early childhood education profession (Standard 6)

› Engaging in reective practice and

continuous learning (Standard 6)

Aligned with InTASC Model Core Teaching

Standards: Early childhood educators work in concert with

the rest of the birth through grade 12 teaching workforce. As

such, the Professional Standards and Competencies for Early

Childhood Educators are aligned with the larger education

eld’s understanding of eective teaching, as expressed

through the Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support

Consortium (InTASC) Model Core Teaching Standards.

Integrated content: Diversity, equity, inclusive practices,

and the integration of technology and interactive media do

not have separate standards; rather, these important content

areas are elevated and integrated in the context of each

standard. Included in each standard and its associated key

competencies are examples of how the content areas apply

to early childhood educators working with particular age

bands of children—infants and toddlers, preschoolers, and

early elementary age children. Whether or not examples are

found in a competency, though, the intention is that every

competency applies across the birth through age 8 continuum.

Intentionally higher-level language: The language used

in the standards and competencies is based in the science of

human learning and development and reects the technical

language of research and evidence used in the early childhood

profession. In their preparation, early childhood educators

will be introduced to the terminology and concepts found

throughout this document.

Simplied structure: The major domains of competencies

are captured in six core standards. Each standard describes

in a few sentences what early childhood educators need to

know and be able to do. It is important to note, then, that

the expectation is not just that early childhood educators

know something about child development and the science

of eective learning—the expectation is more specic

and complex. Each standard comprises three to ve key

competencies to clarify its most important features. These

key competencies break out components of each standard,

highlighting what early childhood educators need to know,

understand, and be able to do. A supporting explanation

tied to each key competency describes how candidates

demonstrate that competency.

Leveling of the standards and competencies to

ECE I, II, and III: The recommendations in the Unifying

Framework lay out three designations with associated scopes

of practice for early childhood educators–ECE I, ECE II, and

ECE III. Appendix A serves as a guide for the profession in

articulating expectations for mastery of the standards and

competencies at each level.

To nd the resources listed in the Introduction and the following standards and competencies, please see Appendix D.

A POSITION STATEMENT HELD ON BEHALF OF THE EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION PROFESSION | 8

Professional Standards

and Competencies for

Early Childhood Educators:

Summary

9 | PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

STANDARD 1

Child Development and

Learning in Context

Early childhood educators (a) are

grounded in an understanding of

the developmental period of early

childhood from birth through age

8 across developmental domains.

They (b) understand each child as an

individual with unique developmental

variations. Early childhood educators

(c) understand that children learn and

develop within relationships and within

multiple contexts, including families,

cultures, languages, communities,

and society. They (d) use this

multidimensional knowledge to make

evidence-based decisions about how

to carry out their responsibilities.

1a: Understand the developmental

period of early childhood from

birth through age 8 across physical,

cognitive, social and emotional,

and linguistic domains, including

bilingual/multilingual development.

1b: Understand and value each

child as an individual with unique

developmental variations, experiences,

strengths, interests, abilities, challenges,

approaches to learning, and with

the capacity to make choices.

1c: Understand the ways that child

development and the learning process

occur in multiple contexts, including

family, culture, language, community,

and early learning setting, as well

as in a larger societal context that

includes structural inequities.

1d: Use this multidimensional

knowledge—that is, knowledge about

the developmental period of early

childhood, about individual children,

and about development and learning

in cultural contexts—to make evidence-

based decisions that support each child.

STANDARD 2

Family–Teacher Partnerships

and Community Connections

Early childhood educators understand

that successful early childhood

education depends upon educators’

partnerships with the families of the

young children they serve. They (a)

know about, understand, and value

the diversity in family characteristics.

Early childhood educators (b) use this

understanding to create respectful,

responsive, reciprocal relationships

with families and to engage with them

as partners in their young children’s

development and learning. They (c) use

community resources to support young

children’s learning and development

and to support children’s families,

and they build connections between

early learning settings, schools, and

community organizations and agencies.

2a: Know about, understand, and

value the diversity of families.

2b: Collaborate as partners with families

in young children’s development and

learning through respectful, reciprocal

relationships and engagement.

2c: Use community resources to

support young children’s learning and

development and to support families,

and build partnerships between

early learning settings, schools, and

community organizations and agencies.

STANDARD 3

Child Observation, Documentation,

and Assessment

Early childhood educators (a)

understand that the primary purpose

of assessments is to inform instruction

and planning in early learning settings.

They (b) know how to use observation,

documentation, and other appropriate

assessment approaches and tools. Early

childhood educators (c) use screening

and assessment tools in ways that are

ethically grounded and developmentally,

culturally, ability, and linguistically

appropriate to document developmental

progress and promote positive outcomes

for each child. In partnership with

families and professional colleagues,

early childhood educators (d) use

assessments to document individual

children’s progress and, based on the

ndings, to plan learning experiences.

3a: Understand that assessments

(formal and informal, formative and

summative) are conducted to make

informed choices about instruction and

for planning in early learning settings.

3b: Know a wide range of types of

assessments, their purposes, and

their associated methods and tools.

3c: Use screening and assessment tools

in ways that are ethically grounded and

developmentally, ability, culturally, and

linguistically appropriate in order to

document developmental progress and

promote positive outcomes for each child.

3d: Build assessment partnerships with

families and professional colleagues.

A POSITION STATEMENT HELD ON BEHALF OF THE EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION PROFESSION | 10

STANDARD 4

Developmentally, Culturally,

and Linguistically Appropriate

Teaching Practices

Early childhood educators understand

that teaching and learning with young

children is a complex enterprise, and its

details vary depending on children’s ages

and characteristics and on the settings

in which teaching and learning occur.

They (a) understand and demonstrate

positive, caring, supportive relationships

and interactions as the foundation for

their work with young children. They

(b) understand and use teaching skills

that are responsive to the learning

trajectories of young children and to

the needs of each child. Early childhood

educators (c) use a broad repertoire

of developmentally appropriate and

culturally and linguistically relevant,

anti-bias, and evidence-based teaching

approaches that reect the principles

of universal design for learning.

4a: Understand and demonstrate

positive, caring, supportive

relationships and interactions as

the foundation of early childhood

educators’ work with young children.

4b: Understand and use teaching

skills that are responsive to the

learning trajectories of young

children and to the needs of each

child, recognizing that dierentiating

instruction, incorporating play as a

core teaching practice, and supporting

the development of executive function

skills are critical for young children.

4c: Use a broad repertoire of

developmentally appropriate, culturally

and linguistically relevant, anti-bias,

evidence-based teaching skills and

strategies that reect the principles

of universal design for learning.

STANDARD 5

Knowledge, Application, and

Integration of Academic Content

in the Early Childhood Curriculum

Early childhood educators have

knowledge of the content of the

academic disciplines (e.g., language

and literacy, the arts, mathematics,

social studies, science, technology and

engineering, physical education) and of

the pedagogical methods for teaching

each discipline. They (a) understand

the central concepts, the methods and

tools of inquiry, and the structures in

each academic discipline. Educators

(b) understand pedagogy, including

how young children learn and process

information in each discipline, the

learning trajectories for each discipline,

and how teachers use this knowledge

to inform their practice They (c) apply

this knowledge using early learning

standards and other resources to

make decisions about spontaneous

and planned learning experiences

and about curriculum development,

implementation, and evaluation to

ensure that learning will be stimulating,

challenging, and meaningful to each child.

5a: Understand content knowledge—

the central concepts, methods and

tools of inquiry, and structure—and

resources for the academic disciplines

in an early childhood curriculum.

5b: Understand pedagogical content

knowledge—how young children

learn in each discipline—and how

to use the teacher knowledge and

practices described in Standards 1

through 4 to support young children’s

learning in each content area.

5c: Modify teaching practices by

applying, expanding, integrating, and

updating their content knowledge in

the disciplines, their knowledge of

curriculum content resources, and

their pedagogical content knowledge.

STANDARD 6

Professionalism as an Early

Childhood Educator

Early childhood educators (a) identify

and participate as members of the early

childhood profession. They serve as

informed advocates for young children,

for the families of the children in

their care, and for the early childhood

profession. They (b) know and use

ethical guidelines and other early

childhood professional guidelines. They

(c) have professional communication

skills that eectively support their

relationships and work young children,

families, and colleagues. Early

childhood educators (d) are continuous,

collaborative learners who (e) develop

and sustain the habit of reective and

intentional practice in their daily work

with young children and as members of

the early childhood profession.

6a: Identify and involve themselves

with the early childhood eld and

serve as informed advocates for young

children, families, and the profession.

6b: Know about and uphold

ethical and other early childhood

professional guidelines.

6c: Use professional communication

skills, including technology-mediated

strategies, to eectively support young

children’s learning and development

and to work with families and colleagues.

6d: Engage in continuous, collaborative

learning to inform practice.

6e: Develop and sustain the

habit of reective and intentional

practice in their daily work with

young children and as members of

the early childhood profession.

11 | PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

Professional Standards and Competencies

for Early Childhood Educators

Becoming a professional early childhood educator means developing

the capacity to understand, reect upon, and integrate all six of these

professional standards. It is the integrated understanding of the

following that denes a professional early childhood educator:

› Child development

› Each individual child

› Family and community contexts and other inuences on

individual development and the ability to build respectful

reciprocal relationships with families and communities

› The use of observation and assessment to

learn what works for each child and for young

children as a community learning together

› The use of a repertoire of appropriate pedagogical practices

› Early childhood curriculum

› The application of professional knowledge,

disposition, and ethics

To deepen their understanding of and ability to navigate

complex situations, early childhood educators develop

a habit of reective practice, including integrating their

knowledge and practices across all six standards in order to

create optimal learning environments, design and implement

curricula, use and rene instructional strategies, and interact

with children and families whose language, race, ethnicity,

culture, and social and economic status may be very dierent

from educators’ own backgrounds. It is this knowledge and

practice that will allow teachers to transform a new group of

babies in the infant room or a group of second graders on the

rst day of school into a caring community of learners.

STANDARD 1

Child Development and Learning in Context

Early childhood educators (a) are grounded in an understanding of the developmental

period of early childhood from birth through age 8 across developmental domains.

They (b) understand each child as an individual with unique developmental variations.

Early childhood educators (c) understand that children learn and develop within

relationships and within multiple contexts, including families, cultures, languages,

communities, and society. They (d) use this multidimensional knowledge to make

evidence-based decisions about how to carry out their responsibilities.

A POSITION STATEMENT HELD ON BEHALF OF THE EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION PROFESSION | 12

Key Competencies and Supporting Explanations

1a: Understand the developmental period of

early childhood from birth through age 8 across

physical, cognitive, social and emotional, and

linguistic domains, including bilingual/multilingual

development. Early childhood educators base their

practice on the profession’s current understanding of the

developmental progressions and trajectories of children

birth through age 8 and on generally accepted principles

of child development and learning. They are familiar with

current research on the processes and trajectories of child

development, and they are aware of the need for ongoing

research and theory building that includes multicultural and

international perspectives.

Educators consider multiple sources of evidence (e.g., research,

observations from practice, professional resources) to expand

their understanding of child development and learning. Their

foundational knowledge across multiple interrelated areas

encompasses the physical, cognitive, social and emotional,

and linguistic domains, including bilingual/multilingual

development; early brain development, including executive

function; and the development of learning motivation and life

skills. They understand the roles of biology and environment;

the importance of interactions and relationships; the critical

role of play; and the impact of protective factors as well

as the impact of stress and adversity on young children’s

development and learning. They know and can discuss

the theoretical perspectives and research that ground this

knowledge and continue to shape it.

1b: Understand and value each child as an individual

with unique developmental variations, experiences,

strengths, interests, abilities, challenges, and

approaches to learning, and with the capacity to

make choices. Early childhood educators learn about

each child through observation, open-ended questions,

conversations, reections on children’s work and play, and

reciprocal communication with children’s families. They

understand that developmental variations among children

are normal, that each child’s progress will vary across

domains and disciplines, and that some children will

need individualized supports for identied developmental

delays or disabilities.

1c: Understand the ways that child development

and the learning process occur in multiple contexts,

including family, culture, language, community, and

early learning setting, as well as in a larger societal

context that includes structural inequities. Early

childhood educators know that young children’s learning and

identity are shaped and supported by their close relationships

with and attachments to adults and peers and by the cultural

identities, languages, values, and traditions of their families

and communities. Early childhood educators know that young

children are developing multiple social identities that include

race, language, culture, class, and gender, among others.

Educators recognize the benets to children of growing up

as bilingual/multilingual individuals and the importance of

supporting the development of children’s home languages.

Early childhood educators understand that all children and

families are widely impacted by society’s persistent structural

inequities related to race, language, gender, social and

economic class, immigration status, and other characteristics,

which can have long-term eects on children’s learning and

development. They know that young children are more likely

than any other age group to live in poverty, and they understand

how poverty and income inequality impact children’s

development. Early childhood educators understand how

trauma and stress experienced by young children and their

families, such as violence, abuse, serious illness and injury,

separation from home and family, war, and natural disasters,

can impact young children’s learning and development.

Early childhood educators also understand that early

childhood programs are communities of learners that have

the potential for long-term inuence on children’s lives.

They recognize the role that early education plays in young

children’s short- and long-term physical, social, emotional,

and psychological health and its potential as a protective

factor in children’s lives. They understand that they as early

childhood educators, along with the social and cultural

contexts of early learning settings, inuence the delivery of

young children’s education and care.

13 | PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

1d Use this multidimensional knowledge—that

is, knowledge about the developmental period

of early childhood, about individual children,

and about development and learning in cultural

contexts—to make evidence-based decisions that

support each child. To support each child and build a

caring community of children and adults learning together,

early childhood educators engage in continuous decision

making by integrating their knowledge of the following three

aspects of child development: (a) principles, processes, and

trajectories of early childhood development and learning;

(b) individual variations in children’s development and

learning; and (c) children’s development and learning in

dierent contexts. Teachers apply this knowledge across all

six standards presented here, as they build relationships with

children, families, and communities; conduct and use child

assessments; select and reect upon their teaching practices;

develop and implement curricula; and think about their own

development as professional early childhood educators. In

doing so, they create learning environments that are safe,

healthy, respectful, culturally and linguistically responsive,

supportive, and challenging for each young child by

› Promoting children’s physical and psychological

health, safety, and sense of security

› Demonstrating respect for each child as a

feeling, thinking individual and respect for

each child’s culture, home language, individual

abilities, family context, and community

› Building on the cultural and linguistic assets that

each child brings to the early learning setting

› Communicating their belief in children’s ability

to learn through play, spontaneous activities, and

guided investigations, helping all children understand

and make meaning from their experiences

› Constructing group and individual learning experiences

that are both challenging and supportive and by applying

their knowledge of child development to provide

scaolds that make learning achievable and that stretch

experiences for each child, including children with

special abilities, disabilities, or developmental delays.

STANDARD 2

Family–Teacher Partnerships and Community Connections

Early childhood educators understand that successful early childhood education depends

upon educators’ partnerships with the families of the young children they serve. They

(a) know about, understand, and value the diversity in family characteristics. Early

childhood educators (b) use this understanding to create respectful, responsive, reciprocal

relationships with families and to engage with them as partners in their young children’s

development and learning. They (c) use community resources to support young children’s

learning and development and to support children’s families, and they build connections

between early learning settings, schools, and community organizations and agencies.

A POSITION STATEMENT HELD ON BEHALF OF THE EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION PROFESSION | 14

Key Competencies and Supporting Explanations

2a: Know about, understand, and value the diversity

of families. Early childhood educators understand that

each family is unique. They know about the role of parents

(or those serving in the parental role) and about family

development, the diversity of families and communities,

and the many inuences on families and communities.

Early childhood educators have a knowledge base in family

theory and research and the ways that various factors

create the home context in young children’s lives: social and

economic conditions; diverse family structures, cultures and

relationships; family strengths, needs and stressors; and home

language and cultural values. They recognize that families

who share similar socioeconomic and racial and/or ethnic

backgrounds are not monolithic but are diverse in and of

themselves. Early childhood educators understand how to

build on family assets and strengths.

2b: Collaborate as partners with families in young

children’s development and learning through

respectful, reciprocal relationships and engagement.

Early childhood educators take primary responsibility

for initiating and sustaining respectful and reciprocal

relationships with children’s families and other caregivers;

they work with them to support young children’s positive

development both inside and outside the early learning setting.

Teachers learn with and from families, recognizing and

drawing on families’ expertise about their children for insight

into curriculum, program development, and assessment. Early

childhood educators strive to honor families’ preferences,

values, childrearing practices, and goals when making

decisions about young children’s development and care. They

share information with families about their children in ways

that families can understand and use at home, using families’

preferred communication methods and home languages as

much as possible.

When collaborating with families, early childhood educators

employ a variety of communication methods and engagement

skills, including informal conversations when parents pick

up and drop o children, more formal conversations in

teacher–family conference settings, and reciprocal technology-

mediated communications, such as phone calls, texting, or

emails. They help families and children with transitions at

home, such as adapting to a new sibling, and with transitions

to new services, programs, classrooms, grades, or schools.

Early childhood educators reect on their own values and

potential biases in order to make professional decisions

that arm each family’s culture and language(s) (including

dialects) and that demonstrate respect for various family

structures and beliefs about parenting.

2c: Use community resources to support young

children’s learning and development and to

support families, and build partnerships between

early learning settings, schools, and community

organizations and agencies. Early childhood educators

demonstrate knowledge about a variety of community

resources and use them to support young children’s learning

and development and families’ well-being. These might

include community cultural resources, mental health services,

early childhood special education and early intervention

services, health care organizations, housing resources, adult

education classes, adult courses in English as a second

language, translation/interpretation services, and economic

assistance resources. Educators help families to nd high-

quality resources and to partner with other early childhood

experts (e.g., speech pathologists, school counselors), as

needed, to support young children’s development and learning.

Regardless of their own work settings, all early childhood

educators contribute to building respectful, reciprocal

partnerships with the various early learning programs and

schools in their communities, as well as with community

organizations and agencies, through activities such as

sharing information about or organizing visits to libraries or

museums, participating in community events, visiting re

houses, helping children get to know their neighborhood, and

partnering with other programs and schools to support child

and family condence and continuity during transitions.

15 | PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

STANDARD 3

Child Observation, Documentation, and Assessment

Early childhood educators (a) understand that the primary purpose of assessment is

to inform instruction and planning in early learning settings. They (b) know how to use

observation, documentation, and other appropriate assessment approaches and tools.

Early childhood educators (c) use screening and assessment tools in ways that are ethically

grounded and developmentally, culturally, ability, and linguistically appropriate to document

developmental progress and promote positive outcomes for each child. Early childhood

educators (d) build assessment partnerships with families and professional colleagues.

Key Competencies and Supporting Explanations

3a: Understand that assessments (formal and

informal, formative and summative) are conducted

to make informed choices about instruction and for

planning in early learning settings. Early childhood

educators understand that child observation, documentation,

and other forms of assessment are central to the practice of

all early childhood professionals. They are close observers of

children. Educators understand that assessment is a positive

tool that can build continuity in young children’s development

and learning experiences. They understand that eective,

evidence-based teaching is informed by thoughtful, ongoing

systematic observation and documentation of each child’s

learning progress, qualities, strengths, interests, and needs.

They understand the importance of using assessments that

are consistent with and connected to appropriate learning

goals, curricula, and teaching strategies for individual young

children. Early childhood educators understand the essentials

of authentic and strengths-based assessment—such as age-

appropriate approaches and culturally relevant assessment

in a language the child understands and assessment that is

conducted by a speaker of the child’s home language—for

infants, toddlers, preschoolers, and children in early grades

across developmental domains and curriculum areas.

3b: Know a wide range of types of assessments,

their purposes, and their associated methods and

tools. Early childhood educators are familiar with a variety

of formative, summative, qualitative, and standardized

assessments. They know a wide range of formal and informal

observation methods, documentation strategies, screening

tools, and other appropriate resources, including technologies

that facilitate assessments and approaches to assessing young

children that help teachers plan experiences that scaold

children’s learning. Early childhood educators understand

the strengths and limitations of each assessment method and

tool. They understand the components of the assessment cycle

and concepts of assessment validity and reliability as well as

the importance of systematic observations, interpreting those

observations, and reecting on observations’ signicance for

and impact on their teaching.

A POSITION STATEMENT HELD ON BEHALF OF THE EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION PROFESSION | 16

3c: Use screening and assessment tools in ways

that are ethically grounded and developmentally,

ability, culturally, and linguistically appropriate

in order to document developmental progress and

promote positive outcomes for each child. Educators

embed assessment-related activities in the curriculum and

in daily routines to facilitate authentic assessment and to

make assessment an integral part of professional practice.

They create and take advantage of unplanned opportunities

to observe young children in play and in spontaneous

conversations and interactions as well as in adult-structured

assessment contexts. Early childhood educators analyze

data from a variety of assessment tools and use the data

appropriately to inform teaching practices and to set learning

and developmental goals for young children.

They understand assessment issues and resources, including

technology, related to identifying and supporting young

children with diering abilities, including children whose

learning is advanced, those who are bilingual or multilingual

learners, and children with developmental delays or

disabilities. They seek assistance, when needed, on how to

assess a particular child. This might mean reaching out to

colleagues who can bring new understanding, experience,

or perspective related to child and family ethnicity, culture,

or language. For example, a bilingual colleague may be

better prepared to successfully observe a child’s receptive

and expressive language skills, social interaction skills, and

emerging reading skills in both the child’s home language and

second language.

Early childhood educators know about potentially harmful

uses of inappropriate or inauthentic assessments and of

inappropriate assessment policies in early education. If

culturally or linguistically appropriate assessment tools are

not available for particular young children, educators are

aware of the limitations of the available assessments. When

not given the autonomy to create or select developmentally

appropriate, authentic assessments due to the setting’s

policies, such as the use of standardized, normative

assessments in pre-K through grade 3 settings, early

childhood educators exercise professional judgment and work

to minimize the adverse impact of inappropriate assessments

on young children and on instructional practices. They use

developmental screenings to bring resources and supports to

children and families and to avoid excluding children from

educational programs and services. They advocate for and

practice asset-based approaches to assessment and to the use

of assessment information.

Early childhood educators use assessment practices that

reect knowledge of legal and ethical issues, including

condentiality and the use of current professional practices

related to equity issues. In order to ensure fairness in their

assessments of young children, early childhood educators

consider the potential for implicit bias in their assessments,

their ndings, and the use of their ndings in creating plans

for supporting young children’s learning and development.

3d: Build assessment partnerships with families

and professional colleagues. Early childhood educators

partner with families and with other professionals to

implement authentic asset-based assessments and to develop

individualized goals, curriculum plans, and instructional

practices that meet the needs of each child. They recognize the

assessment process as collaborative and open, and they benet

from shared analyses and use of assessment results while

respecting condentiality and following other professional

guidelines. They encourage self-assessment in children

as appropriate, helping children to think about their own

interests, goals, and accomplishments.

Early childhood educators particularly ensure that assessment

results and the planning based on those results are conveyed

using jargon-free explanations that are easily understood

by families, teaching teams, and colleagues from other

disciplines. Teachers recognize that their responsibility is to

identify, but not diagnose, children who have the potential for

a developmental delay or disability or for advanced learning.

They know when to refer families for further assessment by

colleagues with specialized knowledge in a relevant area. Early

childhood educators participate as professional partners in

Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) teams for children

birth to age 3 and in Individualized Education Program (IEP)

teams for children ages 3 through 8.

17 | PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

STANDARD 4

Developmentally, Culturally, and Linguistically

Appropriate Teaching Practices

Early childhood educators understand that teaching and learning with young children is a

complex enterprise, and its details vary depending on children’s ages and characteristics

and on the settings in which teaching and learning occur. They (a) understand and

demonstrate positive, caring, supportive relationships and interactions as the foundation

for their work with young children. They (b) understand and use teaching skills that

are responsive to the learning trajectories of young children and to the needs of

each child. Early childhood educators (c) use a broad repertoire of developmentally

appropriate and culturally and linguistically relevant, anti-bias, and evidence-based

teaching approaches that reect the principles of universal design for learning.

Key Competencies and Supporting Explanations

4a: Understand and demonstrate positive, caring,

supportive relationships and interactions as the

foundation of early childhood educators’ work

with young children. They understand that all teaching

and learning are facilitated by caring relationships and that

children’s lifelong dispositions for learning, self-condence,

and approaches to learning are formed in early childhood.

When working with young children, early childhood

educators know that positive and supportive relationships

and interactions are the foundation for excellence in teaching

practice with individual children as well as the foundation for

creating a caring community of learners.

They know that how young children expect to be treated

and how they treat others is signicantly shaped in the early

learning setting. Early childhood educators understand that

each child brings his or her own experiences, knowledge,

interests, motivations, abilities, culture, and language to

the early learning setting and that part of the educator’s

role is to build a classroom culture that respects and builds

on this reality (Standard 1). They develop responsive,

reciprocal relationships with individual babies, toddlers, and

preschoolers and with young children in early school grades.

As such, teaching practices might include

› Integrating informal child observation throughout

various routines and activities in the day and using

those observations to learn about each child’s

strengths, challenges, and interests to guide

teachers’ decisions about teaching strategies and

curriculum implementation; and to build positive

relationships with each child and between children

› Providing a secure, consistent, responsive relationship as

a safe base from which young children can explore and

tackle challenging problems and can develop self-regulation,

social and emotional skills, independence, responsibility,

perspective-taking skills, and cooperative learning skills to

manage or regulate their expressions of emotion and, over

time, to cope with frustration, develop resilience, learn

to take on challenges, and manage impulses eectively

› Integrating young children’s home languages and cultures

into the environment and curriculum through materials,

music, visual arts, dance, literature, and storytelling

4b: Understand and use teaching skills that are

responsive to the learning trajectories of young

children and to the needs of each child, recognizing

that dierentiating instruction, incorporating

play as a core teaching practice, and supporting

the development of executive function skills are

critical for young children. Early childhood educators

understand that teaching young children requires teaching

skills and strategies that are responsive to and appropriate for

individual children’s ages, development, and characteristics

and the social and cultural family contexts in which they live.

They understand that dierentiating instruction based on

professional judgment about individual children or groups

of young children—including children who use multiple

A POSITION STATEMENT HELD ON BEHALF OF THE EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION PROFESSION | 18

languages or dialects, children whose learning is advanced,

and children who have developmental delays or disabilities

in order to help them meet important goals is at the heart of

developmentally appropriate practice.

Early childhood teachers understand the importance of

both self-directed play and guided play, as well as the role of

inquiry, in young children’s learning and development across

domains and in the academic curriculum. Early childhood

educators are familiar with the types of play (e.g., solitary,

parallel, social, cooperative, onlooker, fantasy, physical,

constructive) and with strategies to extend learning through

play across the full age and grade span of early education.

They understand that play helps young children develop

symbolic and imaginative thinking, peer relationships,

language (both English and the home language), physical

skills, and problem-solving skills.

Early childhood educators understand the importance of

helping children develop executive function and life skills,

including ability to focus, self-regulation, perspective taking,

critical thinking, communicating, remembering, making

connections, taking on challenges, cooperating, resolving

conicts, solving problems, moving toward independence,

feeling condent, planning, and participating in self-

directed, engaged learning in early childhood. They know

that these skills are developed through supportive, scaolded

interactions with adults and are critical for school readiness

and ongoing success. Early childhood educators know about

learning and diverse motivation theories, environmental

design, instructional design, and the appropriate and

intentional use of technology and interactive media to

enhance and improve access to learning.

As such, teaching practices might include

› Dierentiating instructional practices to respond

to the individual strengths, needs, abilities,

social identity, home culture, home language,

interests, motivations, temperament, and positive

and adverse experiences of each child

› Setting challenging and achievable goals for each

child across physical, social, emotional, and cognitive

domains; helping children set their own goals, as

appropriate; and adjusting support to scaold

and/or extend young children’s learning

› Stimulating and extending multiple forms of play as

part of young children’s learning to help them develop

symbolic and imaginative thinking, peer relationships,

social skills, language, creative movement, and

problem-solving skills; play would include imitative

play and social referencing in babies; solitary, parallel,

social, cooperative, onlooker, fantasy, physical,

and constructive play in toddlers, with increasing

complexity and skills in preschool and early grades

4c: Use a broad repertoire of developmentally

appropriate, culturally and linguistically relevant,

anti-bias, evidence-based teaching skills and

strategies that reect the principles of universal

design for learning. Educators apply knowledge

about ages, abilities, cultures, languages, interests, and

experiences of individual and groups of young children in

making professional judgments about the use of materials,

the organization of indoor and outdoor physical space

and materials, and the management of daily schedules

and routines. All decisions about and use of instructional

approaches and the learning environment are grounded in

and promote positive, caring, and supportive relationships

with and between young children.

While not exhaustive, the repertoire of practices to draw

upon across the birth-through-age-8 early childhood

period includes those addressed in 4a and 4b as well as the

following practices:

Creating the physical and social environments

› Arranging indoor and outdoor environments

that are physically and emotionally safe

› Using consistent schedules and predictable

routines as part of the curriculum

› Providing time, space, and materials to encourage

child-initiated play and risk taking and allowing

children space to roll, crawl, run, jump, exercise, and

engage in both ne and gross motor activities

› Designing teaching and learning environments that

adhere to the principles of universal design for learning

by incorporating a variety of ways for young children to

gain access to the curriculum content, oering multiple

teaching strategies to actively engage children, and

including a range of formats to enable all children to

respond and demonstrate what they know and have learned

19 | PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

› Selecting materials and arranging the indoor and outdoor

environments to create social and private spaces, oer

restful and active spaces, designate spaces for ne and

gross motor development, and create learning centers to

stimulate inquiry, problem solving, practice, and exploration

in foundational concepts in each curriculum area

› Using interactive media and technology with young

children in ways that are appropriate for individuals

and the group, that are integrated into the curriculum,

that provide equitable access, and that engage children

in problem solving, creative play, and interactions as

well as expanding their digital communication and

information capabilities in a safe and secure manner

› Using the environment and the curriculum to stimulate

a wide range of interests and abilities in children of

all genders, avoiding the reinforcement of gender

stereotypes and countering sexism and gender bias

› Engaging children as co-constructors of the environment

to help them express and represent their interests and

understandings, care for and take joy in nature, and

develop positive approaches to learning, participating in

school, and building relationships with peers and teachers

Advancing academic knowledge

› Integrating informal child observation throughout

various routines and activities in the day and using

those observations to inform decisions about teaching

strategies and curriculum implementation

› Integrating early childhood curriculum content into projects,

play, and other learning activities that reect the specic

interests of each child or of groups of children to help them

make meaning of curriculum content and to incorporate

playful learning from infancy through the early grades

› Engaging in genuine, reciprocal conversations with

children; eliciting and exploring children’s ideas;

asking questions that probe and stimulate children’s

thinking, understanding, theory-building, and shared

construction of meaning; encouraging and arming

young children’s self-expression while respecting various

modes of communication; fostering oral language and

communication skills; modeling desired behaviors

and language; and providing early literacy experiences

both in English and in children’s home languages

Providing social and emotional

support and positive guidance

› Responding to stress, adversity, and trauma in young

children’s lives by providing consistent daily routines,

learning the calming strategies that work best for individual

children, anticipating individual children’s dicult

experiences and oering comfort and guidance during those

experiences, supporting the development of self-regulation

and trust, and seeking help from colleagues, as needed

› Using varied approaches to positive guidance strategies

for individual children and groups, such as supporting

transitions between activities, modeling kindness and

respect, providing clear rules and predictable routines,

directing and redirecting behavior, and scaolding

peer conict resolution to help children learn skills for

regulating themselves, resolving problems, developing

empathy, trusting in early childhood educators, and

developing positive attitudes about school

Using culturally and linguistically relevant

anti-bias teaching strategies

› Becoming aware of implicit biases and working with

colleagues and families to use positive and supportive

guidance strategies for all children to help them

navigate multiple home and school cultural codes,

norms, and expectations and to prevent suspensions,

expulsions, and other disciplinary measures that

disproportionately aect young children of color

› Incorporating accurate age-appropriate and individually

appropriate and relevant information about ethnic,

racial, social and economic, gender, language, religious,

and LGBTQ+ groups in curriculum and instruction

› Confronting and teaching about racism and other -isms

as they arise in the classroom and on the playground and

addressing biases and stereotypes in books and

other resources used in the classroom in ways

that are developmentally appropriate for toddlers,

preschoolers, and children in early grades

› Using the home languages of children, as appropriate, in

the classroom to help them learn the content at the same

level as their English-speaking peers and to allow them to

use all of their linguistic assets to learn, and dierentiating

instruction for dual language learners to ensure they

learn the content while they are learning English

A POSITION STATEMENT HELD ON BEHALF OF THE EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION PROFESSION | 20

STANDARD 5

Knowledge, Application, and Integration of Academic

Content in the Early Childhood Curriculum

Early childhood educators have knowledge of the content of the academic disciplines

(e.g., language and literacy, the arts, mathematics, social studies, science, technology and

engineering, physical education) and of the pedagogical methods for teaching each discipline.

They (a) understand the central concepts, methods and tools of inquiry, and structures in each

academic discipline. Educators (b) understand pedagogy, including how young children learn

and process information in each discipline, the learning trajectories for each discipline, and how

teachers use this knowledge to inform their practice. They (c) apply this knowledge using early

learning standards and other resources to make decisions about spontaneous and planned

learning experiences and about curriculum development, implementation, and evaluation

to ensure that learning will be stimulating, challenging, and meaningful to each child.

Key Competencies and Supporting Explanations

5a: Understand content knowledge—the central

concepts, methods and tools of inquiry, and

structure—and resources for the academic disciplines

in an early childhood curriculum. Early childhood

educators know how to continuously update and expand

their own knowledge and skills, turning to the standards of

professional organizations in each content area and relying on

sound resources for their own development, for curriculum

development, and for selection of materials for young children

in the following disciplines.

Early childhood educators understand that

› Language and literacy learning are foundational not

just for success in school but for lifelong success in

communication, self-expression, understanding of the

perspectives of others, socialization, self-regulation,

and citizenship. Early childhood educators know that

listening, speaking, reading, writing, storytelling, and

visual representation of information are all methods of

developing and applying language and literacy knowledge

and skills. They understand essential elements of language

and literacy, such as semantics, syntax, morphology, and

phonology, and of reading, such as phonemic awareness,

phonics decoding, word recognition, uency, vocabulary,

and comprehension. Early childhood educators understand

the components and structures of informational texts and

of narrative texts, including theme, character, plot, and

setting. They are aware that oral language, print, and

storytelling are similar and dierent across cultures, and

they are familiar with literature from multiple cultures.

› The arts—music, creative movement, dance, drama, visual

arts—are primary media for human communication,

inquiry, and insight. Educators understand that each of

the arts has its own set of basic elements, such as rhythm,

beat, expression, character, energy, color, balance, and

harmony. They are familiar with a variety of materials

and tools in each of the arts and with the arts’ diverse

styles and purposes across cultures. Educators know

that engagement with the arts includes both self-

expression and appreciation of art created by others.

They value engagement in the arts as a way to express,

communicate, and reect upon self and others and upon

culture, language, family, community, and history.

› Mathematics is a language for abstract reasoning and

critical thinking and is used throughout life to recognize

patterns and categories, to make connections between

what is the same and what is dierent, to solve real-

world problems, and to communicate relationships and

concepts. Early childhood educators are familiar with

the concepts that underlie counting and cardinality and

number and operations. They understand algebraic and

geometric concepts such as equal/not equal, lines and

space, and estimation and measurement. They know that

the tools for mathematical inquiry include observation,

comparison, reasoning, estimation and measurement,

generation and testing of theories, and documentation

through writing, drawing, and graphic representation.

21 | PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS AND COMPETENCIES FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATORS

› Social studies is a science used to understand and think

about the past, the present, and the future and about self

and identity in society, place, and time. Early childhood

educators know that the eld of social studies includes

history, geography, civics, economics, anthropology,

archeology, and psychology—and that all of these areas

of inquiry contribute to our ability to make meaning

of our experiences, think about civic aairs, and make

informed decisions as members of a group or of society.

They are familiar with central concepts that include social

systems and structures characterized by both change

and continuity over time; the social construction of

rules, rights, and responsibilities that vary across diverse

groups, communities, and nations; and the development of

structures of power, authority, and governance and related

issues of social equity and justice. They know that oral

storytelling, literature, art, technology, interactive media,

artifacts, and the collection and representation of data are

all tools for learning about and exploring social studies.

› Science is a practice that is based on observation,

inquiry, and investigation and that connects to and uses

mathematical language. Early childhood educators

understand basic science concepts such as patterns, cause

and eect, analysis and interpretation of data, the use

of critical thinking, and the construction and testing of

explanations or solutions to problems. They are familiar

with the major concepts of earth science, physical science,

and the life sciences. They are familiar with and can use

scientic tools that include, for example, technology,

interactive media, and print to document science

projects in text, graphs, illustrations, and data charts.

› Technology and engineering integrate and employ concepts,

language, principles, and processes from science and

mathematics to focus on the design and production of

materials and devices for use in everyday life, school, the