www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

1

An Everyman Inside of a Superman: A Cluster Analysis of Action

Comics #1

Rebekah Hayes

In 1938, a cultural icon was created, spurring America towards a rhetoric of

superheroes who surpassed the capabilities of humanity yet remained

uncorrupted by immense power. The icon was Superman, and he was introduced

to the world in Action Comics #1 written by Jerry Siegel and illustrated by Joe

Schuster. Superman is highly relevant because of his long, important history as

an American icon and the symbolism he represents in modern culture. Part of his

symbolism is contained in his role as the first superhero. It is widely accepted

that Siegel and Schuster’s “Superman” gave birth to the concept of the superhero

and inspired every superhero story that came after him (Coogan; Tye). In the last

few decades, superhero films and television shows have permeated people’s

screens in astounding numbers. With this genre saturation comes a need to

understand the origin story of the superhero archetype in order to comprehend

the arguments that underlie the modern comic book and the abundance of

superhero narratives. That archetype is contained within Superman, specifically

within the pages of his debut comic.

Importantly, like any other argument that is crafted, Siegel and Schuster had

underlying perceptions of the world that were undeniably integrated into

Superman from his first appearance in Action Comics #1. The field of rhetoric is

uniquely suited to analyze the arguments embedded within Superman as it is the

study of argumentation. Because comic books are a visual medium, it is vital the

images that portray Superman are a subject of analysis. However, while studies

of Superman’s history can be seen as adjacent to rhetorical understandings

(Regalado; Tye), there are few formal visual rhetorical studies of Superman’s

debut, and they are limited by their methods (Cross; Paris).

In order to accomplish a formal rhetorical study of Action Comics #1, this study

adopts a unique methodology that is suited to analyze comic book images:

cluster criticism. Cluster criticism identifies key terms that have elements that

“cluster” around them, suggesting a rhetor’s conscious or unconscious meaning

for their text (Foss 63-66). Although the method is not exclusively visual, this

project explores the use of cluster criticism in visual applications by analyzing the

enduring visual rhetoric of Superman’s comic debut. The concept that key terms

cluster around a visual element is valuable to studying comic books because

comics are reliant on messages conveyed to an audience through images, not

just the conversations, thoughts, and narratives conducted within text bubbles or

boxes. Additionally, Kathaleen Reid, an important scholar of cluster criticism,

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

2

called for the study of more applications of visual cluster criticism. Thus, using

cluster criticism will open a new path into Superman’s rhetorical meaning and

further current understandings of cluster criticism by applying it to a new medium.

Due to Superman’s importance, the limited rhetorical study of his debut, and the

usefulness of cluster criticism, this project will use cluster criticism to analyze the

visual rhetoric of Superman in Action Comics #1 and answer specific queries.

First, based on the visual clusters around Superman, what is the rhetorical

meaning of Superman embedded within his debut? Second, knowing that cluster

criticism is an analytic methodology with unique value for visual analysis that has

seemingly gone unused in the rhetorical analysis of comic books, implementing

this technique should examine the effectiveness of cluster criticism in relation to

comic books. This will be achieved by understanding whether new rhetorical

meaning emerges from Action Comics #1 using this method. Thus, I seek to

answer the following questions: Does cluster analysis provide a new

understanding of Superman’s debut? As an American symbol, what does

Superman’s rhetorical meaning argue about America in 1938, and how might that

meaning be relevant today?

Literature Review

Before this article answers the designated research questions, it is important to

delve into relevant research to understand current perspectives on Superman

(Tye; Regaldo), the rhetorical analyses that have been conducted about early

Superman comics (Cross; Paris), and the method that will be applied in this

article (Foss; Reid).

Histories and Cultural Studies of Superman

When investigating Superman’s rhetorical meaning, historical and cultural studies

are valuable although they often indirectly provide insight into Superman’s

symbolism. Within the available historical research on Superman, Larry Tye’s

book Superman: The High-Flying History of the Man of Steel is a notable

biographical account of Superman’s creators. In this history, Tye investigates

elements of Superman’s rhetorical symbolism, although he does not claim this

investigation as a rhetorical study. For example, Tye asserts that Superman’s

Jewish creators, Siegel and Schuster, include many references to Judaism, such

as allusions to the biblical character Moses and the fact that Superman’s birth

name “El” originates in the Hebrew language (Tye 65). While Tye offers insight

into seemingly intentional symbolism embedded in Superman comics due to his

creators’ biographies, his book is a biography and history rather than a rhetorical

study of visual elements of Superman comics.

In contrast to Tye’s work, the book Bending Steel: Modernity and the American

Superhero, by Aldo J. Regalado, explores Superman’s significance as a

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

3

progenitor of various heroes. In his study, Regalado identifies various

intersecting rhetorical frames that informed Superman’s introduction, such as

“the American Revolution’s rhetoric of freedom,” opposition to “modernity,” “the

Great Depression,” “anti-Semitism,” and “aggressive white masculinity” (18, 80,

102). While Regalado’s claims are useful, he does not perform a formal rhetorical

analysis because his project is a cultural analysis that stretches beyond

Superman. Furthermore, Regalado does not provide close visual analysis of

Superman comics as he takes a broad view of many superheroes.

Rhetorical Analyses of Superman

Although indirect rhetorical studies are useful, formal rhetorical arguments about

Superman are needed. In my research, I found only masters’ theses which

addressed early Superman comics in the field of rhetoric. Importantly, in David J.

Cross’s masters’ thesis, he interprets Superman by examining “rhetorical studies

of historic events,” and examining visual and textual elements of Superman

comics through a historical lens (13). Cross finds that Superman supports

modernity, which greatly contrasts with Regalado’s interpretation of Superman as

opposing modernity (23). Also, Cross claims Action Comics #1 promotes

isolationism through a narrative in which Superman confronts a lobbyist (64).

Cross’s methodology combines visual rhetoric and history but does not use a

particular method to collect significant images and does not spend extensive time

collecting the overall meaning in Action Comics #1.

Another relevant work regarding the rhetoric of Superman is Sevan M. Paris’s

rhetorical analysis of Superman through his thesis How to Be a Hero: A

Rhetorical Analysis of Superman’s First Appearance in “Action Comics.” Paris’s

thesis examines “how Superman’s creators accomplished the rhetorical

heightening visually” in order to influence children to be engaged in a type of

heroism feasible for children, such as defending innocent peers (6). To Paris,

rhetorical heightening is an element that emphasizes the importance of specific

messages. Paris argues that rhetorical heightening, such as through panel

structure, was used to persuade children to employ everyday heroism. While

Paris’s findings are valuable, he focuses on Superman’s audience as children

which discounts the value of interpreting the comic as a literary artifact which has

evolved beyond a juvenile audience and has influenced adults.

Cluster Criticism

In contrast to the methods used by Cross and Paris, the rhetorical method of

cluster criticism for visual artifacts relies on a systematic identification of

important elements. Cluster criticism is a process in which an artifact is examined

by a rhetorician who identifies “key terms,” visuals or words that recur or are

significant, then categorizes “cluster terms,” recuring words or visuals that are

“clustered” around the key terms (Foss 63-65). In my search of visual cluster

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

4

criticism, I did not locate any research in which cluster criticism has analyzed

Superman or comic books.

Furthermore, although Kenneth Burke, the originator of cluster criticism, did not

focus on cluster criticism as a method of visual analysis, in her article, “The Hay-

Wain: Cluster Analysis in Visual Communication,” Kathaleen Reid adapts cluster

criticism to analyze Hieronymus Bosch’s painting the Hay-Wain and proves the

value of cluster criticism in analyzing artifacts from visual media. However, Reid

finds visual artifacts offer limited elements to help identify cluster terms, visual

analysis must account for the ways visual artifacts differ from textual artifacts,

and “multiple realities” may arise due to scholarly interpretation (Reid 51-52).

Reid concludes, “Despite these issues that arise from the application of cluster

analysis, the rhetorical perspective helps open the door for more research

regarding visual communication” (52). Ultimately, Reid found that cluster criticism

is a viable rhetorical approach to visual rhetorical scholarship, and she suggests

scholars investigate various applications.

Having surveyed historical, cultural, and rhetorical approaches to Superman

comics, it is apparent that studies of Superman can be further developed. Tye

and Regalado provide knowledge based on history and culture, but neither

author studies the character within a rhetorical frame nor do they provide close

analysis of Superman’s debut. In contrast, Cross and Paris work within the field

of rhetoric, but Cross does not focus enough on the method of selecting images

and Paris’s findings limit Superman’s meaning to an audience of children rather

than examining how Superman inspired an entire genre of comics that have

influenced contemporary American adults. After considering alternative rhetorical

methods for analyzing Superman, I have concluded that visual cluster criticism

(as articulated by Foss) is a useful methodology for selecting images to analyze.

The following study will offer insight into cluster criticism’s ability to uncover more

unconscious rhetorical meanings embedded in Superman and will answer

Kathaleen Reid’s call to investigate cluster criticism’s viability with an array of

visual media by analyzing a comic book.

Method

Due to the need for formal rhetorical analyses of Superman that allow for both

the enduring legacy of the character and choosing images through a clearer

methodology, this study will implement cluster criticism as defined by Foss. In

selecting a comic book to analyze, many of Kathaleen Reid’s concerns about

applying cluster criticism to visual artifacts were addressed. For instance, the

length of a comic book means the artifact provides sufficient data to draw

connections between clusters and key terms; comics also rely on sequencing

their stories and conveying a message to readers, thereby answering Reid’s

concern about art and language not having a sense of past and present. Further,

because Reid encourages implementing cluster criticism on a broader array of

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

5

artifacts, this analysis of Action Comics #1 serves to answer Reid’s call for further

study of the usefulness of cluster criticism to analyze a variety of visual artifacts.

Regarding methodology, Sonja K. Foss provides a clear process to conduct

cluster criticism. Foss describes how to conduct a cluster analysis: “The first step

in cluster criticism is to select the key terms. Your key terms should be nouns”

(64). The next step in cluster analysis is “identifying each occurrence of each key

term and charting the terms that cluster around each key term” (65). For visual

cluster analysis, Foss recommends identifying “representational images or visual

aspects of the key terms” (65). Thus, this project includes a chart organizing

identified cluster images around identified key terms and those cluster images

will be the cluster terms (see Figure 1). Although Foss recommends identifying

key terms and cluster terms based on “frequency and intensity,” to limit the scope

of this project, I have used only Superman/Clark Kent as the key term for the

visual analysis to determine the rhetorical meaning Siegel and Schuster

embedded in Superman (64-67). Thus, in this project Superman is the visual key

term and representational images that surround him will be visual cluster terms.

The Artifact

Action Comics #1 was published in 1938 and contains stories other than the

origin of Superman, but for the purpose of this study, only Superman’s narrative

will be analyzed. Action Comics #1 begins by describing Superman’s origin on a

distant, culturally, and scientifically advanced planet (Siegel and Schuster). Infant

Superman is rocketed to Earth, taken in by an orphanage, and begins to exhibit

extraordinary powers and promises to help humanity. The first narrative features

Superman locating proof of innocence for a woman on death row, leading him to

barge into the governor’s home to obtain the woman’s pardon. In the second

narrative, Clark Kent hears of an abuse case. He becomes Superman and

confronts the man abusing his wife. Later, Clark asks Lois Lane, his coworker at

the newspaper, to go dancing with him and she reluctantly agrees. An aggressive

man, named Butch, tries to force Lois to dance with him, and Clark passively

defends her. When Lois leaves Clark at the roadhouse, she is followed and

kidnapped by Butch. Subsequently, Superman pursues Butch’s green car, and

Superman hoists Butch onto telephone lines. In the next narrative, the

newspaper editor sends Clark to Washington D.C. After listening to a lobbyist,

named Greer, coercing a senator to vote for wartime interference, Superman

follows Greer and carries him through the heights of the Capitol to terrorize him

into altering his behavior.

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

6

Visual Cluster Analysis

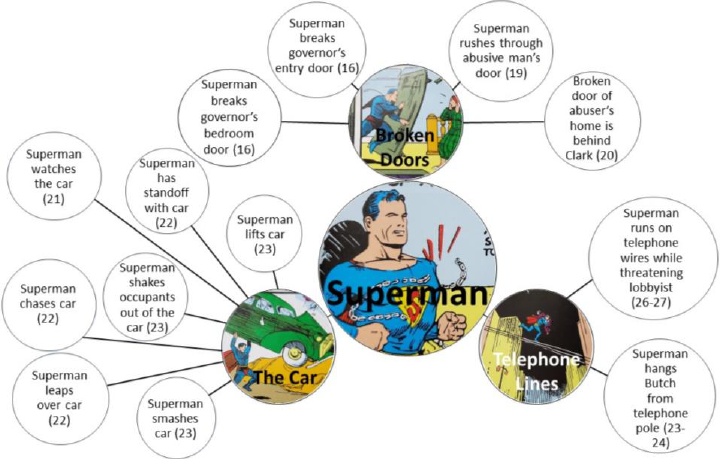

Figure 1: Chart of visual clusters identified around Superman; Action Comics #1

by Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster, in Action Comics 80 Years of Superman: The

Deluxe Edition, edited by Paul Levitz and Liz Erikson, DC Comics, 2018, pp. 16,

23, 26, 27.

As previously discussed, to limit the scope of this project, “Superman” and “Clark

Kent” will be the key term in this cluster analysis. The character is prominent

throughout Action Comics #1 as the focal point of each part of the narrative,

making him meet Foss’s rule of “frequency and intensity” (67). Much discussion

of Superman’s costume and appearance has already been conducted nullifying

the use of these details as providing new context through cluster criticism. Also,

because Superman is in nearly every panel, visuals cluster around him easily,

increasing the importance of “frequency and intensity” in identifying visual cluster

terms associated with him. In order to identify viable visual clusters, Foss’s

description of identifying clustered terms in the form of “representational images”

is implemented in the identification of cluster terms (65). Around Superman, the

following visual cluster terms have been identified: the green car, broken doors,

and telephone lines (see fig. 1).

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

7

The Green Car

Figure 2: Various panels in Superman’s encounter with the green car; Action

Comics #1 by Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster, in Action Comics 80 Years of

Superman: The Deluxe Edition, edited by Paul Levitz and Liz Erikson, DC

Comics, 2018, p. 22-23.

Arguably the most prominent and identifiable cluster term associated with

Superman is the iconic green car. Featured on the cover of Action Comics #1

and a vital part of Superman’s pursuit to rescue Lois, the green automobile

meets Foss’s guideline of intensity (see Figure 2). Superman is frequently framed

with the vehicle from the moment of its introduction (Siegel and Schuster 21-23).

However, the negative use of the car and Superman’s interactions with it suggest

Superman is opposed to the rhetoric embedded in this automobile.

Before the most famous panel in which Superman smashes the car, Superman

was shown pursuing the car. First, he stood in front of the vehicle, almost daring

the car to run him over; then, he leapt over the speeding vehicle, allowing him to

chase it, capture it, and shake the occupants violently from the interior (Siegel

and Schuster 22-23). Next, in a replication of the cover (except for the missing

third man cowering in fear), Superman raises the car above his head in a move

of impossible strength. In this panel, the front of the car is slightly crumpled,

showing Superman has already begun to shatter the car (see Figure 2). Multiple

motion lines along the sides of the car represent the downward motion and

incredible speed at which Superman is breaking the vehicle (see Figure 2).

Screaming men flee away from Superman and this terrifying scene ends with

Butch running towards the reader (see Figure 2). While the textual narrative has

assured readers that Superman is the protagonist and a paragon of virtue, each

visual detail reveals strength, speed, destruction, and terror that evokes a sense

that Superman is dangerous.

Within this panel, the car has come to represent the power, status, and control

that Butch and his companions had exerted, but are now made impotent by

Superman’s power. Subtle evidence made the car a representation of Butch’s

control. Of course, Butch’s suit matches the car and signals a relationship

between the two, but it is his use of the car that signals its relationship to Butch’s

control. The symbolism of control is particularly clear in the previous panels in

which the car was the weapon Butch attempted to level at Superman when

attempting to run him down (Siegel and Schuster 22). In these panels, the action

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

8

flows against expectation as Superman is on the right side of the panels and the

green car moves from the left toward the right. The expectation would be for the

protagonist to move left to right as this is the direction American comics are read

(Potts 91). Thus, putting the car on the side of panels usually occupied by

protagonists indicates it has greater narrative beyond the power of a singular

man, Superman.

However, when Superman leaps over the car the action is reversed. In the third

panel in Figure 2, the car appears to be heading in a different direction, yet it

remains on the same path. This disruption in “action flow,” which is the

consistency of direction in comic books, supports that the physical weapon of the

car loses its power over Superman. In comics, artists can choose to “have all

protagonists in a story move with that natural left-to-right eye flow until the

protagonist . . . experiences a reversal in his or her journey” (Potts 91). Although

Potts suggests there is flexibility in the variety of ways that artists can use the

reversal of action flow, it seems Superman’s leap over the car signals a switch

from Butch having control to Superman possessing greater influence.

Additionally, the camera switch converts Superman from passively standing to

becoming aggressive and frightening to the men. Specifically, in the iconic panel,

Superman literally wrests Butch’s power from him, shatters that symbol of

control, and terrifies the occupants who were using their power to take people

like Lois. Thus, Superman’s destruction of the green car is an assault on toxic

uses of control achieved through wealth and proves he is equally dangerous to

its occupant for whom it is a symbol.

Additionally, within the historical context of Siegel and Schuster’s writing, the car

is symbolic of an industry that wasted the city of Cleveland and an instrument of

alienation. Siegel and Schuster’s home city of Cleveland had significant negative

associations with the automobile industry, “six motor manufacturers were based

[t]here in the decades after 1900. The 1930s Depression, however, initiated a

period in which the decline of its industrial base destroyed much of Cleveland's

economic strength” (“Cleveland”). Meaning, in the home city of Superman’s

creators, the widespread economic downturn in the automobile industry was

detrimental, causing automobiles to represent the loss of economic stability.

Furthermore, during this era the automobile was connected to alienation of

people from other drivers and pedestrians. The invention of the stoplight in

Cleveland showed how cars could be a source of disconnection among people

(Nelson 1). Thus, the car represents both the economic devastation of the Great

Depression and the individual’s alienation from humanity. So, when the lay

reader viewed the car, connotations of economic downturns and distance from

other people were evident. This is furthered when considering how the car is

used as a tool to try to run down an individual in the road. The alienation that was

associated with the car dividing the ability to recognize others’ humanity is

understood through the attempt to kill Superman. Thus, Superman’s destruction

of this symbol places him in the position of adversary to the rhetoric embedded

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

9

within this cluster term. Superman’s rhetorical opposition to the powerful is

evident through his taking their control, status, and power from them, and the

same action conveys opposition to loss of livelihoods and supports connection

with humanity.

Broken Doors

Figure 3: Superman and the various broken doors panels; Action Comics #1 by

Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster, in Action Comics 80 Years of Superman: The

Deluxe Edition, edited by Paul Levitz and Liz Erikson, DC Comics, 2018, pp. 16-

17, 19-20.

Another frequent and intense cluster around Superman is the three broken doors

involved in his storyline. These doors each hold rhetorical meaning that can be

apparent to the average reader: Superman breaks barriers. However, the

doorways also reveal an underlying meaning that Superman is a character who

cannot be held back and can invade every aspect of people’s lives. The repeated

action of breaking doors shows readers Superman can splinter barriers that keep

the average man from intervening in specific aspects of life. “Breaking barriers” is

the phrase that seeing this frequent action evokes, reminding readers of

normative barriers preventing people from going outside of accepted norms.

Each door seems to represent a different barrier that Superman implies should

be ignored, and, as a “superior” human, Superman does ignore them, asking

readers to consider the possibility that these barriers are wrong and should be

removed.

First, the door to the governor’s house seems to represent barriers to justice

because Superman breaks this door to retrieve a pardon (Siegel and Schuster

16-17). Superman jumps through this door, but it remains intact, although

separated from its doorway, implying the barrier is a problem that remains, but

Superman is capable of overcoming it (see Figure 3). This meaning correlates

with Superman’s vow to help those in need. The door to the governor’s bedroom

is representative of the need for citizens to have access to their political

representatives and not be ignored and barred from being heard. Interestingly,

this door is made of metal and should be the most difficult to breach (see Figure

3). Because this door crumples in Superman’s hands rather than flying off its

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

10

hinges or shattering like the other doors, this barrier is the strongest and the most

challenging to Superman (see Figure 3). There is a possible suggestion that it

bends rather than breaks because the law must be accessible and adaptable to

individual situations rather than an inflexible source of punishment. Further,

although it does crumple under Superman’s grip, it was not as easily removed

even by Superman, telling readers, while Superman can triumph over the

barriers to leaders, the barrier is that much greater to the normal citizen (see

Figure 3).

Regarding the door Superman breaks to stop the man beating his wife, this

barrier represents the normative perspectives from the era in which spousal

abuse was to be ignored or accepted. This door is made of wood and the reader

can see a portion of the door is gone when Clark is kneeling over the defeated

man (see Figure 3). The rhetoric involved in this particular barrier is especially

clear when examining the panel in which Clark is told that there is a report of a

man abusing his wife, appearing to run directly from this panel to the next as

Superman, in which we do not see the door, only Superman’s immediate

intervention. Scott McCloud theorizes the space between panels, the gutters,

represents a space in which readers create the scene for themselves (88-93).

When the reader must fill more of the gap, it requires more effort and the shot

that Siegel and Schuster use between Clark hearing about the abuse and his

intervention as Superman is considered a “scene-to-scene” transition (McCloud

74). Although the reader must assume the leap to the location of the abuse, the

connection between Clark and Superman makes it easier to fill the gap. Thus,

the ease of the transition implies that this door or barrier that Superman can

overcome is so thin people can easily see through it and take action. However,

the barrier does exist, and the door must be opened to recognize and act on the

issue. Superman’s interactions with this door compel readers to reinterpret their

perspectives on physical abuse and consider recognizing when abuse is

happening, and then act on that recognition.

Furthermore, there is surprising meaning connected to the cluster of the door of

the abusive man. Of note is the mirroring between the panel in which Superman

arrives to stop the man beating his wife and the panel in which Clark leans over

the man’s prone body (see Figure 3). While there are several panels between the

moment Superman stops the man and the moment the officer arrives, the panels

could be viewed as a set of “transitions featuring a single subject in distinct

action-to-action progressions” because they each feature Superman and the

abusive man fighting (McCloud 70). This creates contrast when there is no longer

action between Superman and the abusive man because Superman changed

back to Clark and adopts a position similar to the one that the abusive man had

held when Superman arrived, and the man has taken the position of his prone

wife. In the same panel, the police officer becomes the subject in action

evidenced by his mirroring Superman’s arrival and his addition to the scene.

In addition to simply mirroring each other, the role changes become alarming

when considering the underlying, likely unintentional, rhetoric about the cycle of

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

11

abuse. By attacking the man, Superman became the abuser, injuring the man the

way the wife was injured. The police officer taking the position of Superman, by

entering through the door, has a connotation that perhaps the police, like

Superman, may have interest in justice, but can be instruments of injustice. This

door is complex visual rhetoric that could be interpreted as a positive message

about intervening in abuse, but it also reveals the dangers of assuming the role

of avenger. Ultimately, the cohesive message that arises from this cluster of

doors around Superman is that Superman stands against norms, representing

anti-normative narratives, which is both frightening and a call to action against

these barriers.

Telephone Lines

Figure 4: Superman and various telephone pole panels; Action Comics #1 by

Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster, in Action Comics 80 Years of Superman: The

Deluxe Edition, edited by Paul Levitz and Liz Erikson, DC Comics, 2018, pp. 23-

24, 26-27.

Another cluster group around Superman is telephone poles and their wires. They

are twice shown as Superman’s apparent method of punishment, making their

appearance an intense association with Superman, and they appear frequently

due to their presence in these multi-panel punishments (see Figure 4). To punish

Butch, Superman climbs a telephone pole near the site of the car chase and

hangs Butch from the telephone pole (see Figure 4). Later, to frighten Greer, the

lobbyist, Superman leaps to the telephone wires in Washington D.C. and races

across them (see Figure 4). These two instances show Superman’s ability to

confidently climb the heights of telephone poles and touch their electrified wires.

The repeated use of telephone poles demonstrates Superman’s intentional use

of a fear tactic to enact retribution upon the villains he deems to have

transgressed against society. This intense use of the telephone lines as a visual

element invites readers to understand the rhetorical meaning of the telephone

poles.

Although they are one cluster term, it seems each use of the telephone poles as

punishment centers around slightly different rhetoric. With Butch’s punishment,

he is hung from the pole and seemingly left there until someone releases him. In

Greer’s punishment, Superman is racing across the wires and uses fear of

electrocution to intimidate Greer, as seen in the dialogue where Greer fears this

outcome and Superman toys with the possibility of being electrocuted (Siegel

and Schuster 26-27). Thus, in Butch’s punishment, the importance of the

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

12

telephone wires as a relatively great height is the focus and it results in a form of

imprisonment because he is unable to free himself from this penalty. While

Greer’s punishment focuses on the wires’ potential electrocution, the height is

still important because Superman is racing over Washington, D.C., which

imposes importance upon the height in this situation as well. Interestingly,

Greer’s punishment is unresolved in Action Comics #1 because it ends on a

cliffhanger, in which Superman leaps from the wires towards a build and claims

he has “missed” the building, thereby intensifying the importance of heights

because Greer is the one that would be harmed by the fall (Siegel and Schuster

27).

Additionally, the telephone poles’ rhetoric of dominance is evident through

understanding their connection to heights. When a person or group has the high

ground, it often means they are going to win an argument because they are

morally superior, but this is a reference to battle tactics which have long

presumed having the highest section of a battlefield will help assure victory

(“Moral”). Thus, heights symbolize moral and physical dominance and

superiority. Superman’s attitude toward the telephone wires can be understood in

his trip with Greer up the telephone wires when Superman displays a half-smile

to assure readers that he is confident and comfortable going to these heights

(see Figure 4). Superman’s dominance over his opponents is clear because in

each case the men are carried and do not have any control over where they are

going while Superman is able to choose to take them to these heights.

Superman’s moral superiority is given to readers through the narrative, but he is

visually superior to the men because he has agency and control over them.

Furthermore, standing above a place and looking down, as Superman does from

the telephone lines, is a classical act of dominance. In the panels in Washington,

D.C., Superman takes this pose to gaze down at the Capitol building, a symbol of

U.S. governance and ideology, implying his dominance over Greer, who is

seemingly representative of corruption in the U.S., and the U.S. government

(Siegel and Schuster 27). In Figure 4, the fourth panel is angled so it appears the

viewer is looking up at Superman on the electrical wires and this angle is an “up-

shot [which] is often used to convey their [characters’] strength” (Janson 105).

Although the perspective is from a distance below Superman and Greer, creating

a sense of height, the angle emphasizes Superman’s power. In his dominance

and power, Superman’s punishment of Greer serves to assert that Superman will

oppose corruption in the government, and he independently has the power to do

so.

Importantly, Superman’s position on the telephone wires of Washington D.C.

shows his dominance comes with perspective. The final panel, Figure 4, is from

behind Superman and looks down on the Capitol building. He can view the

Capitol and the intricacies of the government with a macroscopic perspective that

shows him the danger of venal individuals in a society reliant upon the

government acting in good faith (see Figure 4). Without Superman holding him,

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

13

Greer would fall, indicating his inability to hold onto the larger impact of his

actions on the Capitol. So, Superman’s secure perch at such a great height also

argues he should have power because it grants him perspective to recognize

corruption and act against it. Seemingly, Superman is dominant over his

individual opponents and over the locations where he implements punishments.

Meaning, when Superman enacts his justice on Butch from the heights of the

telephone lines, he displays his superiority to Butch’s financial status and control.

Overall, Superman’s rhetorical dominance shown through the cluster of

telephone poles appears purposefully intimidating. Superman’s continued role as

an American symbol makes this rhetoric especially relevant. If Superman and

America are dominant as pictured in Action Comics #1, then they will set the

norm for what is unacceptable deviance. Without the examination of social or

physical controls on Superman/America, they can dole their version of justice as

an unimpeded imperialistic force. However, because Superman’s punishment is

meant to strike fear in those he deems have transgressed against society, Siegel

and Schuster’s visual grouping of telephone wires also suggests those who do

not deviate from Superman’s vision of “good” have nothing to fear. In these

panels, Superman is not punishing random people; he is enacting “justice” on

people who are traditional symbols of corruption. Butch, as his name implies,

shows an aggressive masculinity that takes whatever he wants and exerts

economic privilege over the working class, and Greer represents a group of

people trying to manipulate the political system for monetary gain. The greater

message conveyed through Superman’s dominance is the people who take

advantage of their political or economic positions may have had uncontested

power, but they can be challenged and their influence disrupted.

Synthesis

As this research about Superman suggests, his debut holds a wide array of

rhetorical arguments. At the same time, though, they all symbolize the need for

systemic change to support those with less social power. Rather than reinforcing

systems, Superman was the opposition to the existing norms. Through the

symbolism of the green car, readers see the economically privileged taking

advantage of those without the benefit of money, calling to mind collapsing

industries devastating people’s livelihoods. Just as automobiles represented

alienation, this also seems to manifest in the form of barriers, doors Superman

must overcome, that separate the citizen from other citizens and representatives.

These barriers, like the car, must be removed to achieve justice for those who

might be unseen and to reconnect society.

As a product of his time, Superman challenged the barriers and empowered

groups preventing the average person from intervening in their world, from

stopping spousal abuse to taking control back from the wealthy and politically

powerful. Superman’s dominance over Butch’s economic privilege, Greer’s

political manipulation, and the government, builds on his destruction of barriers

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

14

and attack on economic privilege; Superman opposes and takes control from

those who misuse their privileges. Butch should not have control and those like

Clark Kent, who understands what it means to be perceived as weak and is an

everyman inside of a superman, deserve to have that power. Superman

ultimately has dominance over the corrupt and his opposition is meant to correct

the systems already in place.

While it is alarming to view the visual of Superman paralleling the role of the

abusive husband, it could be read as precisely the kind of warning that must

accompany a character who is assuming the power of the things he opposes.

Because “power corrupts,” simply accepting Superman’s perfection would be

negligent rhetoric on the part of his creators. Superman uses unparalleled

physically embodied power to confront forms of power that are often invisible. By

creating the symbol of Superman, it seems Siegel and Schuster have created a

visible embodiment to confront those intangible inequities that their 1938

economy and political world was experiencing. By investing these powers in an

alien and not a man, this embodiment is able to rise above the faults of humanity

and use his power for positive change. However, when Superman acts against

rigid barriers and existing disparities it still appears terrifying to endow anyone

with such dominance. Yet, acting against economic, physical, and political abuse

seems to require possessing greater power. After all, it is not Clark Kent who

confronts these foes; it is Superman. Regardless of his moments of apparent

danger, Superman’s powerful interactions bringing change to his world seem to

argue for anyone to do something to confront injustice and corruption. Whether it

is his powerful protection of the woman on death row or his terrifying actions

against Greer, Superman’s rhetoric shows that the America of Action Comics #1

needs someone to push against accepted corruptions and social standards.

Conclusions

Through synthesizing the meanings found in these visual clusters, Superman’s

rhetorical meaning has become evident. Superman represents systemic social

change in corrupt and unaware governing systems. In order to bring change,

Superman seemingly must represent dominance over those imbalanced systems

he opposes. Thus, the destruction of the car and the doors and his punishments

of Butch and Greer show Superman’s rhetorical opposition and dominance over

normative culture, which had allowed alienation from others, economic

devastation, and political manipulation to remain the standard. Thus, this study

affirms the usefulness of cluster criticism in examining comic books and

discovers that Superman’s rhetorical meaning is complicated by his superhuman

ability to overcome and dominate evils of his generation and his own overbearing

justice.

In answer to Superman’s rhetorical meaning in relation to his enduring legacy as

an American symbol, Superman’s multitude of rhetorical meanings argues that

1938 America was imperfect and this meaning continues to be relevant today.

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

15

Superman stood against economic privilege, alienation, and barriers to justice,

suggesting even as America was experiencing these challenges, people like

Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster could envision a country that truly represented the

values of equality and connection. When considering the panels in which

Superman stood against abuse, but inadvertently became the abuser, historic

and contemporary issues in America seem evident. The United States is meant

to stand for justice, but the Black Lives Matter movement, among many other

groups similarly desiring a more just society, reveals that a need still exists for

social movements and narratives that break barriers between the people and

their leaders and access to justice. Even today, America continues to struggle

with equality and acceptance, which makes Siegel and Schuster’s enduring

representation of an answer to inequality relevant for continued study.

Regarding the process of implementing cluster criticism in a comic book issue,

the visual analysis was successful because it revealed more complex

understandings of Superman’s opposition to the economically powerful, his ability

to take power from the undeserving, new analysis of his opposition to specific

barriers, and his dominance over villains and the American government. These

findings support visual cluster criticism as a method that should be implemented

in the rhetorical analysis of comic books. The method revealed insights into

Superman’s rhetorical associations that would not have become apparent without

identifying the key term and noticing the significant clusters around the term

“Superman.” For instance, the use of cluster criticism revealed significant clusters

in the use of doors and telephone wires and the analysis identified the sheer

intensity of the iconic green car. Other methods that do not look for intense and

frequent uses of particular terms in connection to a key term, such as methods

used by Cross and Paris, would not have identified these cluster terms as

significant to the work, but they are essential to recognizing the unconscious

rhetoric embedded in Superman’s origin. Cluster criticism reveals relevant

modern rhetoric about systemic change that Siegel and Schuster embedded in

Superman from his introduction.

Furthermore, future researchers seeking to use cluster criticism to analyze comic

books could compare the rhetoric of Superman’s introduction to newer Superman

narratives, even if those narratives have been studied using different methods or

frameworks. Excellent examples for future study are All-Star Superman by Grant

Morrison, Superman: Red Son by Mark Millar, or Max Landis’s Superman:

American Alien. However, as this study of Action Comics #1 was limited to a

single issue, any application of visual cluster criticism to a series of comic issues,

in a collected volume, would be challenging due to the large number of visual

elements over a series of issues. As such studies are conducted, Reid’s concern

about the array of scholarly interpretation should be considered because the

visual elements in the clusters around Superman did lead to complex

interpretations. Although the array of interpretations can be understood by

connecting them to each other, future studies would likely benefit from choosing

www.xchanges.org

Volume 18, Issues 1 & 2

Spring 2024

www.xchanges.org

Hayes, “An Everyman Inside of a Superman”

16

key terms carefully to manage the various elements that would need to be

analyzed in coordination with each other.

Ultimately, this cluster analysis finds Superman’s role as an American symbol to

claim that America does not possess one homogenous meaning or value.

Instead, America was and is flawed and needs transformation and challengers to

norms. America still needs the ideal of heroes because they can confront barriers

and normative expectations and instill hope that the everyday individual can alter

society for the better. However, with this hopeful belief comes caution about

corrupt power and the actions taken to solve these problems. Although many of

the same struggles evident in Superman’s rhetoric persist in contemporary

American society, they have changed, and like Siegel and Schuster’s Superman

suggests, people can shape the values of America for better or worse.

Works Cited

“Cleveland.” The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather

Guide. 2018.

Coogan, Peter. “Genre: Reconstructing the Superhero in All-Star Superman.”

Critical Approaches to Comics: Theories and Methods, edited by Matthew

J. Smith and Randy Duncan, Routledge, 2012, pp. 203-220.

Cross, David J. An Historical and Visual Rhetorical Analysis of Superman Comic

Books, 1938-1945. 2011. Florida State University, Master’s thesis.

Foss, Sonja K. Rhetorical Criticism: Exploration and Practice. 5

th

ed., Waveland

Press, 2018.

Janson, Klaus. The DC Comics Guide to Pencilling Comics. Watson-Guptill

Publications, 2002.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. William Morrow, 1993.

“Moral.” Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, edited by Susie Dent,

Chambers Harrap, 20th edition, 2018.

Nelson, Megan Kate. “A Brief History of the Stoplight.” Smithsonian Magazine,

May 2018, www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/brief-history-stoplight-

180968734/.

Paris, Sevan M. How to be a Hero: A Rhetorical Analysis of Superman's First

Appearance in “Action Comics.” 2011. University of Tennessee at

Chattanooga, Master’s thesis.

Potts, Carl. The DC Comics Guide to Creating Comics: Inside the Art of Visual

Storytelling. Watson Guptill, 2013.

Regalado, Aldo J. Bending Steel: Modernity and the American Superhero.

University Press of Mississippi, 2015.

Reid, Kathaleen. “The Hay-Wain: Cluster Analysis in Visual Communication.”

Journal of Communication Inquiry, vol. 14, no. 2, 1990, pp. 40-54.

Siegel, Jerry and Joe Schuster. “Action Comics #1.” Action Comics 80 Years of

Superman: The Deluxe Edition, edited by Paul Levitz and Liz Erikson, DC

Comics, 2018, pp. 14-27.

Tye, Larry. Superman: The High-Flying History of America's Most Enduring Hero.

Random House, 2012.