STATE

DEPARTMENT

Pervasive Passport

Fraud Not Identified,

but Cases of

Potentially Fraudulent

and High-Risk

Issuances Are under

Review

Report to Congressional Requesters

May 2014

GAO-14-222

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-14-222, a report to

congressional requesters

May 2014

STATE DEPARTMENT

Pervasive Passport Fraud Not Identified, but

Cases of

Potentially Fraudulent and High-Risk Issuances Are

under Review

Why GAO Did This Study

Fraudulent passports pose a significant

risk because they can be used to

conceal the true identity of the user

and potentially facilitate other crimes,

such as international terrorism and

drug trafficking. State issued over 13.5

million passports during fiscal year

2013.

GAO was asked to assess potential

fraud in State’s passport program. This

report examines select cases of

potentially fraudulent or high-risk

issuances among passports issued

during fiscal years 2009 and 2010—the

most recently available data at the time

GAO began its review. GAO matched

State’s passport data from fiscal years

2009 and 2010 for approximately 28

million issuances to databases with

information about individuals who were

deceased, incarcerated in state and

federal prison facilities, or who had an

active warrant at the time of issuance.

GAO also analyzed the passport data

to identify issuances to applicants who

provided a likely invalid SSN, which

had not been assigned at the time of

the passport application, or had been

publically disclosed. From each of

these five populations, GAO selected

nongeneralizable samples for

additional review. GAO also randomly

selected a generalizable sample from a

population of passport issuances to

applicants who used only the SSN of a

deceased individual. GAO reviewed

State’s adjudication policies, and

examined passport applications for

these populations to further assess

whether there were potentially

fraudulent or high-risk issuances. State

provided technical comments and

generally agreed with our findings. This

report contains no recommendations.

What GAO Found

Of the approximately 28 million passports issued in fiscal years 2009 and 2010

that GAO reviewed, it found issuances to applicants who used the identifying

information of deceased or incarcerated individuals, had active felony warrants,

or used an incorrect Social Security number (SSN); however, GAO did not

identify pervasive fraud in these populations. The Department of State (State)

has taken steps to improve its detection of passport applicants using identifying

information of deceased or incarcerated individuals. In addition, State modified its

process for identifying applicants with active warrants, and has expanded

measures to verify SSNs in real time. GAO referred, and State is reviewing,

matches from this analysis. The following summarizes GAO’s findings:

• Deceased individuals. As shown in the figure, GAO identified at least 1

case of potential fraud in the sample of 15 cases, as well as likely data

errors. State reviewed the cases referred by GAO, and indicated fraud could

likely be ruled out in 9 of the 15 cases; State plans to further review 6 cases.

• State prisoners. GAO found 7 cases of potential fraud among the sample of

14 state prisoner cases. State noted fraud could likely be ruled out in 10 of

the 14 cases, and intends to conduct additional reviews of 4 cases.

• Federal prisoners. None of the 15 cases in this sample had fraud indicators,

since all individuals were not actually in prison when applying for passports.

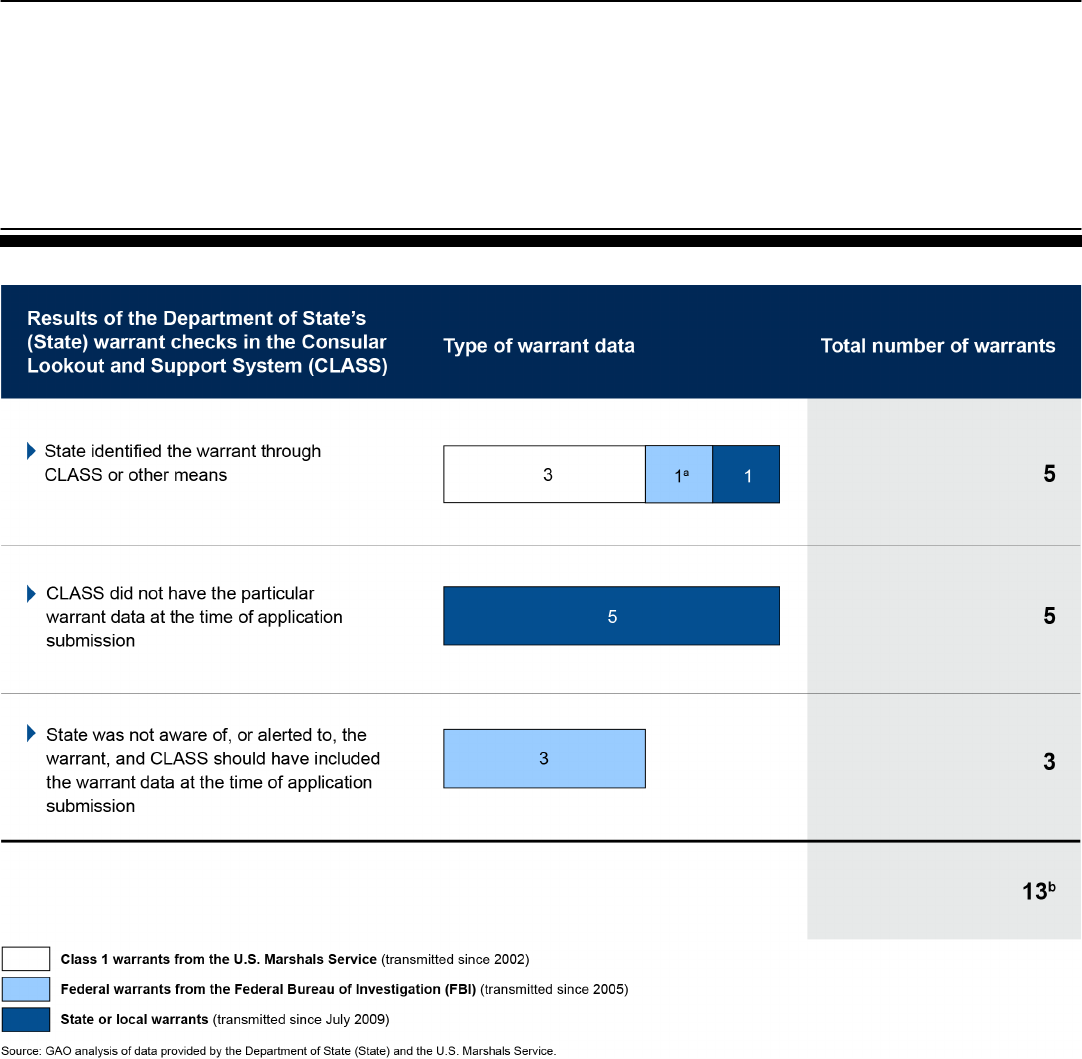

• Individuals with active warrants. GAO found five cases where State

identified the warrant and resolved it prior to issuance. As the figure shows,

GAO also identified three cases with warrants that State was not aware of or

alerted to, but should have been in State’s system for detection during

adjudication.

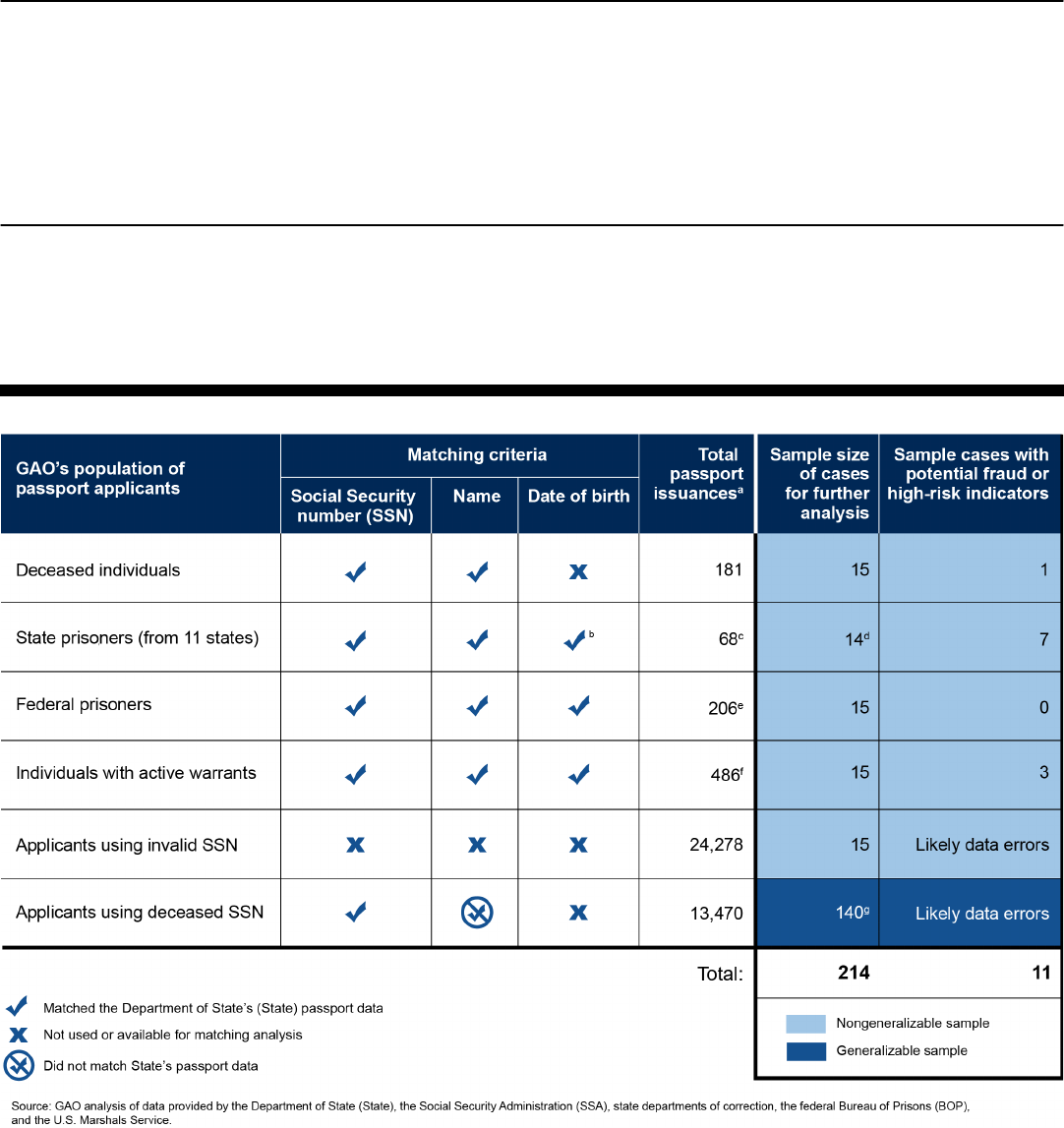

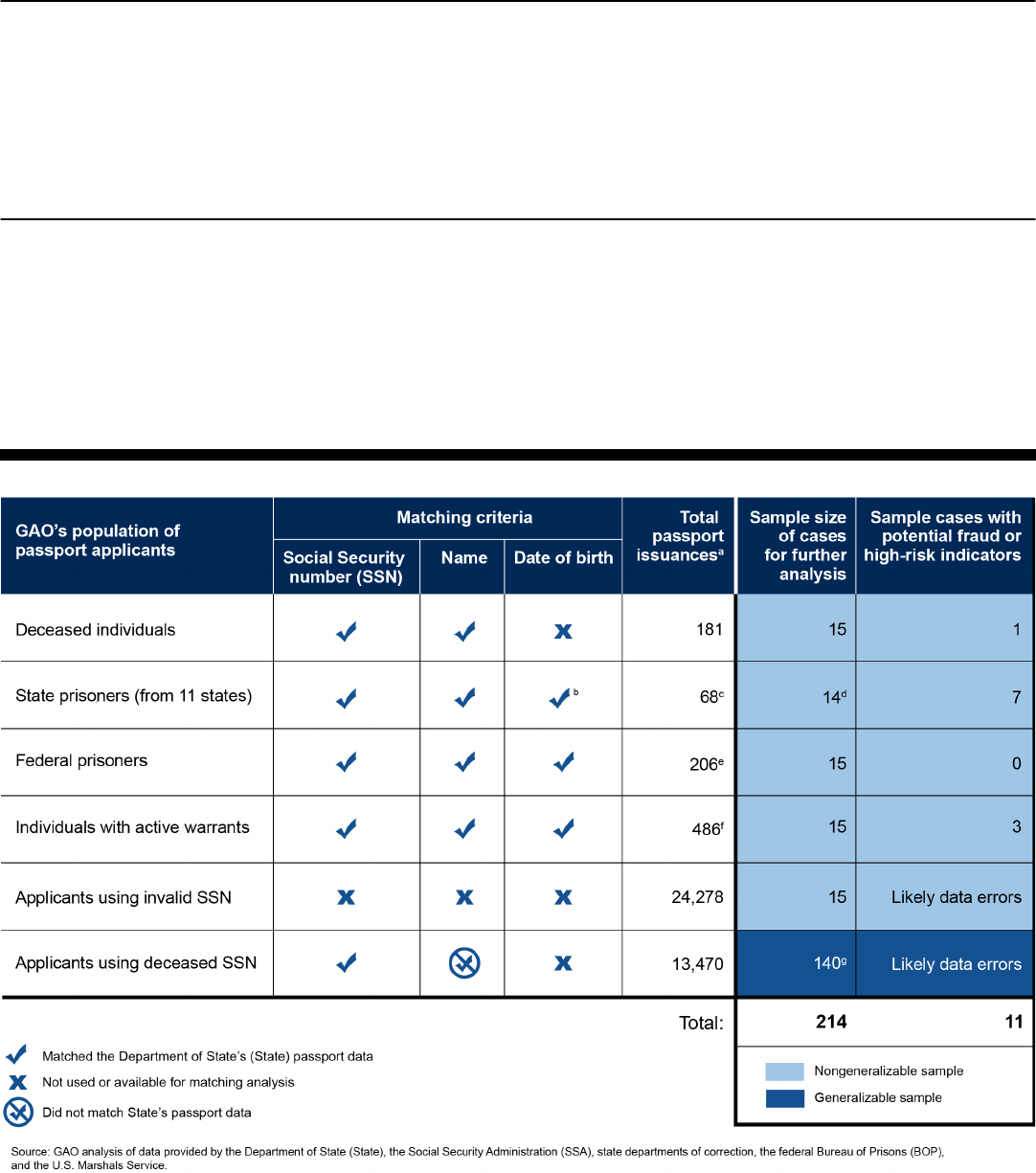

Summary of GAO’s Matching Analysis and Nongeneralizable Samples

a

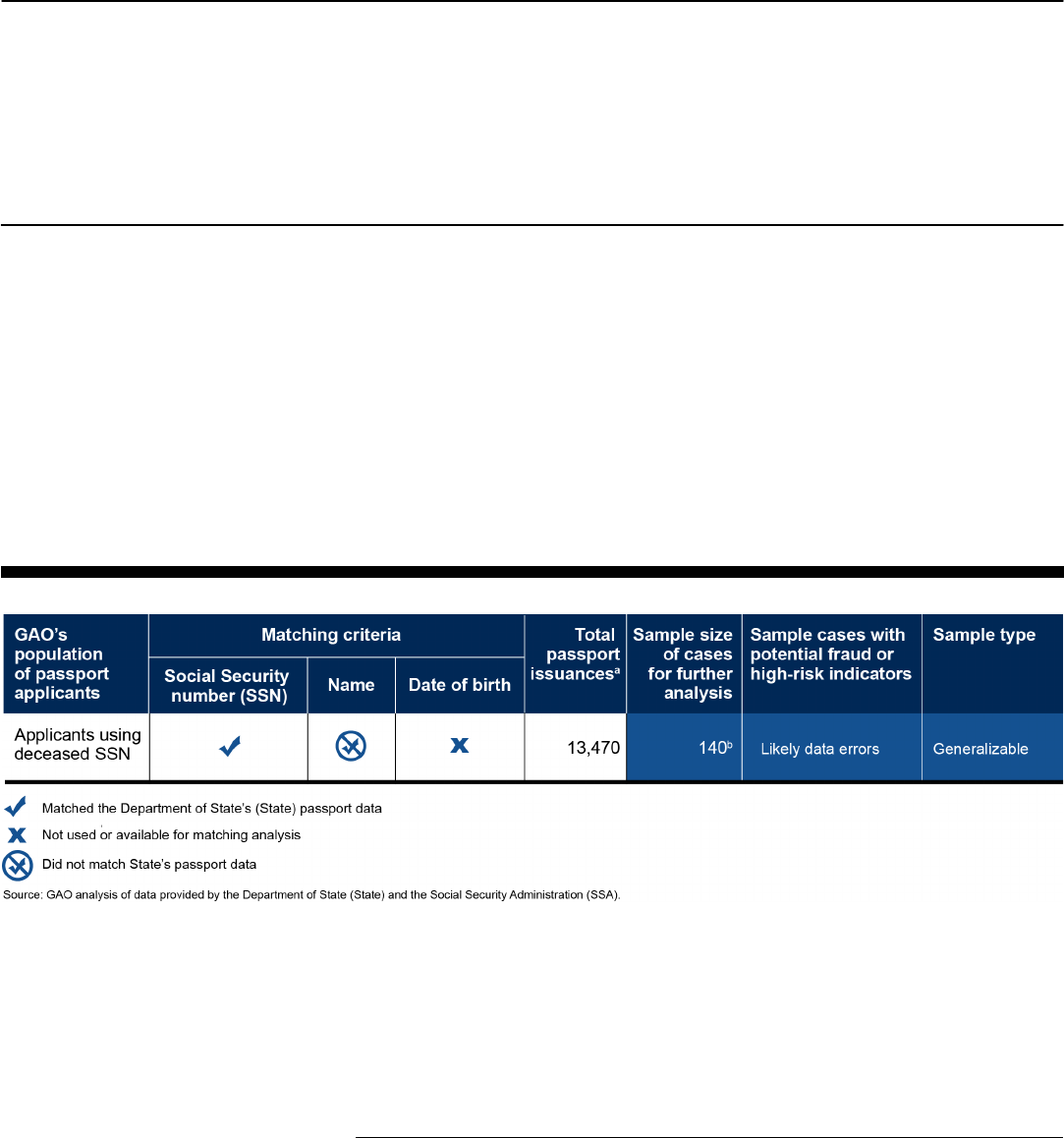

In addition, GAO found 13,470 passport issuances to individuals who used the

SSN, but not the name, of a deceased person, as well as 24,278 issuances to

applicants who used a likely invalid SSN. GAO reviewed a 140-case

generalizable sample and a 15-case nongeneralizable sample for these two

populations, respectively, and determined the cases were likely data errors. State

has taken steps to capture correct SSN information more consistently.

Total passport issuances are solely based on the matching criteria. GAO did not verify that all

issuances from its match populations were actual fraud cases or issuances to individuals with active

warrants. Rather, it selected samples for further review and referred all matches to State.

View GAO-14-222. For more information,

contact Stephen M. Lord at (202) 512-6722 or

Page i GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Letter 1

Background 6

Examples of Potentially Fraudulent or High-Risk Passport

Issuances Found, but Pervasive Fraud Not Identified 13

Agency Comments 30

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 31

Appendix II Passport Application and Adjudication Process 37

Appendix III The Department of State’s (State) Use of the Social Security

Administration’s (SSA) Records for Death Checks 39

Appendix IV Description of Warrant-Matching Analysis 41

Appendix V GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 43

Table

Table 1: Warrants by Type of Offense to Individuals Issued

Passports from Fiscal Years 2009 and 2010 42

Figures

Figure 1: Summary of Matching Analysis and Samples by

Population 4

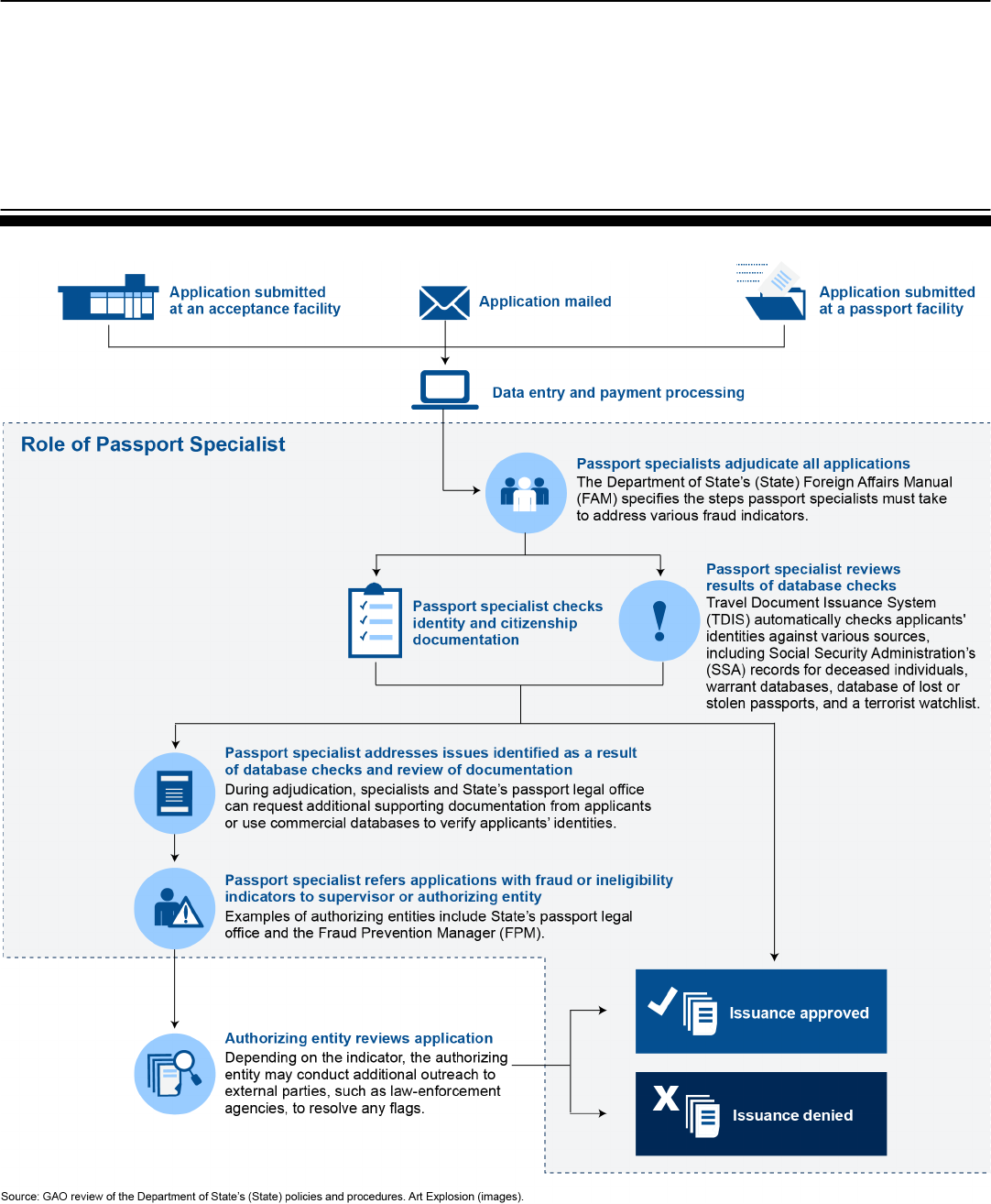

Figure 2: Passport Application and Adjudication Process 8

Figure 3: Description of Matching Analysis and Sample of

Deceased Individuals 14

Figure 4: Summary of Matching Analysis and Sample of State

Prisoners 16

Figure 5: Summary of Matching Analysis and Sample of Federal

Prisoners 18

Contents

Page ii GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Figure 6: Timeline Showing When the Department of State (State)

Began Checking for Federal, State, and Local Warrants 22

Figure 7: Summary of Matching Analysis and Sample of

Applicants with Active Warrants 23

Figure 8: Summary of Whether State Identified the Warrants in

Our Sample Population 24

Figure 9: Summary of Matching Analysis and Sample of

Deceased-SSN Errors 26

Figure 10: Estimated Percentage of Causes of Incorrect SSNs

Associated with Deceased Individuals in State’s Passport

Data 28

Figure 11: Summary of Analysis and Invalid Social Security

Number Sample 29

Figure 12: Summary of Matching Analysis and Samples by

Population 35

Figure 13: Passport Application and Adjudication Process 38

Figure 14: Social Security Administration’s Responses and

Actions of Passport Specialists 40

Page iii GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Abbreviations

BOP Bureau of Prisons

CLASS Consular Lookout and Support System

DS Bureau of Diplomatic Security

EVS Enumeration Verification System

FAM Foreign Affairs Manual

FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation

FinCEN Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

FPM Fraud Prevention Manager

NCIC National Crime Information Center

SSA Social Security Administration

SSN Social Security number

State Department of State

TDIS Travel Document Issuance System

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

May 1, 2014

The Honorable Dianne Feinstein

Chairman

Select Committee on Intelligence

United States Senate

The Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse

Chairman

Subcommittee on Crime and Terrorism

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

The Honorable Benjamin L. Cardin

United States Senate

Fraudulent passports pose a significant risk because they can be used to

conceal the true identity of the user. In addition, according to the

Department of State (State), passport and visa fraud are often committed

in connection with crimes such as international terrorism, drug trafficking,

organized crime, alien smuggling, money laundering, pedophilia, and

murder. As a result, even a few instances of passport fraud can have far-

reaching effects. A passport is an official government document that

conveys certain benefits, such as certifying an individual’s identity,

permitting a citizen to travel abroad, proving citizenship, assisting with

loan applications, and fulfilling other needs not related to international

travel. State issued over 13.5 million passport cards and books during

fiscal year 2013.

Page 2 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Since May 2005, we have issued several reports identifying fraud

vulnerabilities in the passport issuance process.

1

In 2005 and 2007, we

reported on weaknesses in State’s information sharing with other federal

agencies, such as the Social Security Administration (SSA), as well as

opportunities to improve the agency’s oversight of passport acceptance

facilities. In 2010, we tested State’s passport issuance procedures by

using counterfeit documents and the identities of fictitious or deceased

individuals, inducing State to issue five genuine U.S. passports.

2

State

identified two of our seven applications as fraudulent during its

adjudication process; however, we were able to obtain passports using

counterfeit documents in three cases.

3

You asked that we assess potential fraud in State’s passport program.

This report examines select cases of potentially fraudulent or high-risk

issuances among passports issued during fiscal years 2009 and 2010.

We have made several

recommendations beginning in 2005 designed to help reduce passport

fraud, including that State improve information sharing with other federal

agencies, improve execution of passport fraud-detection efforts, and

strengthen internal controls at its passport-acceptance facilities. State

generally concurred with our recommendations and has taken steps to

address them.

1

GAO, State Department: Undercover Tests Show Passport Issuance Process Remains

Vulnerable to Fraud, GAO-10-922T (Washington, D.C.: July 29, 2010); State Department:

Significant Vulnerabilities in the Passport Issuance Process, GAO-09-681T (Washington,

D.C.: May 5, 2009) Addressing Significant Vulnerabilities in the Department of State’s

Passport Issuance Process, GAO-09-583R (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 13, 2009);

Department of State: Undercover Tests Reveal Significant Vulnerabilities in State’s

Passport Issuance Process, GAO-09-447 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 13, 2009); Border

Security: Security of New Passports and Visas Enhanced, but More Needs to Be Done to

Prevent Their Fraudulent Use, GAO-07-1006 (Washington, D.C.: July 31, 2007); and

State Department: Improvements Needed to Strengthen U.S. Passport Fraud Detection

Efforts, GAO-05-477 (Washington, D.C.: May 20, 2005).

2

Suspicious identifying information and documentation included passport photos of the

same investigator on multiple applications; a 62-year-old applicant using a recently issued

Social Security number (SSN); passport and driver’s license photos showing about a 10-

year age difference; as well as the use of a California mailing address, a West Virginia

permanent address and driver’s license address, and a Washington, D.C., phone number

in the same application.

3

In the two remaining cases, State recovered the passports from the mail before they

were delivered.

Page 3 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

To examine potentially fraudulent or high-risk passport issuances in fiscal

years 2009 and 2010,

4

we matched State’s passport-issuance data for

approximately 28 million passport issuances (including passport books

and cards)

5

to databases containing information about individuals who

were (1) deceased, (2) incarcerated in a state prison facility, (3) in the

custody of the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), or (4) the subject of an

active warrant at the time of the passport issuance.

6

We conducted this

matching on the basis of common data elements including Social Security

number (SSN), name, and date of birth. We also analyzed the passport

data to identify issuances to applicants who provided an invalid SSN,

which was defined as an SSN that had not been assigned at the time of

the passport application, or had a high risk of misuse.

7

4

We used data from these fiscal years because they were the most recent, full fiscal years

available at the time State complied with our data request. In addition, for purposes of this

report, potentially fraudulent passport issuances are those that involved an applicant using

someone else’s identity to apply for and receive a passport. We defined high-risk passport

issuances as issuances to individuals who may pose a risk to public safety, but who did

not necessarily steal someone’s identity to apply for a passport, such as people with

active warrants for felony charges.

From each of

these five populations, we selected nongeneralizable samples for further

review. In addition, from a population of 13,470 passport issuances to

applicants who used the SSN, but not the name, of a deceased individual,

we selected a generalizable stratified random sample of 140 passport

issuances, including 70 passport issuances from both fiscal years 2009

5

According to publically available passport issuance statistics, State issued a combined

total of 28,964,775 passports during fiscal years 2009 and 2010. GAO reviewed

domestically issued passports and excluded passports issued by the Special Issuance

Agency to government travelers. We reviewed a total of 28,000,063 passport issuance

records for these fiscal years.

6

Our review included state prison data from 11 states including Alabama, Arizona,

California, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Virginia. We

also obtained state prisoner data from five other states including Illinois, Louisiana,

Michigan, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina, but did not use the data from these sources

for our matching analysis for various reasons, including the absence of key fields or

delays in receiving the data. We selected these 16 states because they had the largest

prisoner populations as of December 31, 2009.

7

Prior to June 25, 2011, the Social Security Administration (SSA) issued SSNs according

to a sequential and geographic logic. SSNs that were issued after fiscal years 2009 and

2010 should not be found in passport data from that time and therefore all SSNs in the

passport data should be subject to SSA’s sequencing logic. In addition, SSNs that have

been publicly disclosed in advertisements or those used as placeholders by data entry

clerks (e.g., 012-34-5678 or 111-11-1111) are at higher risk of misuse, and may represent

a fraud indicator if found in the passport data.

Page 4 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

and 2010. We analyzed these cases to determine whether the applicant

provided the correct SSN and State recorded it incorrectly, or whether the

applicant provided the wrong SSN and State recorded the incorrect SSN

in its system. Figure 1 summarizes the focus of our matching analysis

and the related sample sizes selected for further review.

Figure 1: Summary of Matching Analysis and Samples by Population

a

These totals are solely based on the matching criteria described. We conducted additional reviews to

verify data for the sample items in the next column. We did not verify that all issuances from our

matching analysis were actual cases of fraud or issuances to individuals with active warrants. Rather,

we selected samples for additional review, and referred all matches to State for further investigation.

b

In our data matching, we used state prisoner data from 11 states including Alabama, Arizona,

California, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Virginia. However, even

though we used data from all 11 states during our matching analysis, three of these state prison

databases did not have any valid matches to the passport data. In addition, data from three states did

Page 5 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

not include dates of birth, and therefore records in these databases matched to State’s passport data

based on Social Security number (SSN) and name only.

c

As described in more detail later in this report, our review indicated that some matches may be a

result of identity theft perpetrated by the state prisoner, prior to incarceration, and not the passport

applicant.

d

We selected a nongeneralizable sample of up to two prisoners incarcerated in each of the states we

reviewed for a total of 14 cases from eight different states.

e

This number includes passport issuances to people residing in halfway houses, and therefore may

not represent issuances to individuals using the identities of federal prisoners to apply for a passport.

f

These 486 passport issuances were associated with 442 unique individuals that had a total of 564

open warrants. We did not confirm that all of these warrants were associated with felony charges, but

we excluded warrants with a description of either a “traffic crime” or “misdemeanor” from our analysis.

g

As highlighted in figure 1, we selected a total of 214 passport issuances

for additional review from our five nongeneralizable and one

generalizable samples. For each of the 214 passport issuances selected,

we reviewed a copy of the original passport application, submitted the

SSN from State’s passport data to SSA for verification, and obtained

records of the passport holder’s travel activity from the Financial Crimes

Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a bureau of the U.S. Department of the

Treasury. We also reviewed State’s documentation of additional

investigative steps the agency took, if any, to resolve fraud indicators

during the adjudication of the passports. Where applicable, we obtained

additional documentation about the death, incarceration, or fugitive status

of applicants from federal and state agencies. For this review, we

included only issued passports; we did not examine passport applications

that were rejected by State or abandoned by the applicant. Furthermore,

we did not attempt to identify all possible types of passport fraud.

The generalizable stratified random sample of 140 passport issuances included 70 passport

issuances from both fiscal years 2009 and 2010.

We assessed the reliability of State’s passport data, TECS travel-activity

data provided by FinCEN, SSA’s full death file, state and federal prisoner

data, and data on individuals with open warrants provided by the U.S.

Marshals Service by reviewing relevant documentation, interviewing

knowledgeable agency officials, and examining the data for obvious

errors and inconsistencies.

8

8

TECS is a data repository to support, among other things, law enforcement “lookouts”

and border screening. TECS is owned and managed by the U.S. Customs and Border

Protection with the Department of Homeland Security.

With the exception of prisoner data from five

states, which we did not use, we concluded that all of the data we used

were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report. We examined

State’s policies, guidance, including the Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM),

Page 6 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

and other materials provided to passport specialists. We reviewed

changes to State’s controls since fiscal years 2009 and 2010 with respect

to preventing certain fraudulent or high-risk passport issuances. We also

interviewed State officials, observed the adjudication process at a

passport facility, and reviewed the 214 passport applications in our

samples to further assess whether there were potentially fraudulent or

high risk issuances. For a more-detailed description of our objectives,

scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We performed this audit from March 2010 through May 2014 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

9

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objective. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objective.

According to agency officials and guidance posted on State’s public

website, applicants can apply for a U.S. passport in one of three ways: in

person at an acceptance facility, by mail (for renewal applications), or at a

passport facility that offers acceptance services (typically expedited

applications). Applicants submit documents, such as a birth certificate or

driver’s license, to passport acceptance agents to provide evidence of

citizenship, or noncitizen nationality, and proof of identity. The acceptance

agents are to watch the applicant sign the application, review submitted

documents for completeness, and check for application inconsistencies.

For example, acceptance agents are to assess whether photographs and

descriptions in the identification documents match the applicant. If an

acceptance agent suspects that an applicant has submitted fraudulent

information or exhibits nervous behavior, the acceptance agent is

instructed to accept the application and complete a checklist indicating

9

The extended period required for our review was a result of various factors, including

data-sharing negotiations with State, the time required to receive and review requested

documentation, extensive data preparation and analysis involving multiple agency

databases, and State’s requirement to review all sensitive information on-site at the State

Department.

Background

Passport Application

Process

Page 7 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

the reason for suspected fraud. The agents are to then send the

application, checklist, and photocopy of the identification to State’s Fraud

Prevention Manager (FPM). Acceptance agents are not State employees;

however, State provides training, as well as detailed guidance that

governs their work. State also conducts periodic inspections and audits of

acceptance facilities to ensure compliance with regulations and policies.

According to State officials, the most common way to renew a passport is

by mail. An individual with a passport issued during the previous 15 years

may renew it by submitting a mail-in application, along with the previously

issued passport, a recent photograph, and documentation of a name

change, if applicable. Applications submitted by mail or at an acceptance

facility are sent to a Department of the Treasury contracted lockbox

service provider for data entry and payment processing. The lockbox

service provider converts handwritten or typed text into electronic data

and deposits passport fees paid by the applicant. Once the lockbox data

entry and payment are complete, the electronic data and paper passport

application are sent to passport-issuing facilities around the United States

for adjudication.

Applicants who demonstrate a need for in-person expedited service for

either a first-time issuance or a renewal may submit their applications

directly to a passport-issuing facility. State employees at these facilities

accept passport fees and enter application data directly into State’s

electronic processing system, called the Travel Document Issuance

System (TDIS), before forwarding the application for expedited

adjudication.

Figure 2 provides an overview of the passport application and

adjudication process for applications received in person at an acceptance

facility, by mail, or at a passport facility that offers acceptance services

(see app. 2 for static version of this figure).

Page 8

GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Figure 2: Passport Application and Adjudication Process

Interactive Graphic

Print Version: Click here or go to appendix II.

Application submitted

at a passport facility

Application mailed

Application submitted

at an acceptance facility

Instructions: Roll over the for more information.

Passport specialists adjudicate all applications

Data entry and payment processing

Passport specialist checks

identity and citizenship

documentation

Role of Passport Specialist

Passport specialist reviews

results of database checks

Passport specialist refers applications

with fraud or ineligibility indicators to

supervisor or authorizing entity

Passport specialist addresses issues

identified as a result of database

checks and review of documentation

Authorizing entity

reviews application

Issuance approved

Issuance denied

X

Source: GAO review of the Department of State (State) data. Art Explosion (images).

Page 9 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

As we have noted in previous products, each passport application is to be

individually reviewed by a passport specialist during a process known as

adjudication.

10

State’s FAM specifies the steps passport specialists must

take to address various fraud indicators. According to State documents,

specialists are responsible for reviewing applications and documents

establishing the applicants’ identity and citizenship, as well as conducting

various checks, as described below. Depending on the results of the

adjudication, passport specialists may approve or deny the passport

issuance, conduct additional checks, request more information from the

applicant, or forward the application for additional review by their

supervisor, the FPM, or by offices in Passport Headquarters.

11

Once a

passport has been issued, the application is scanned and archived.

Passports issued to individuals 16 years or older are generally valid for 10

years.

12

Several federal statutes and regulations either require or permit State to

withhold a passport from an applicant in certain situations. For example,

State must withhold passports from individuals who are in default on

certain U.S. loans, who are in arrears of child support in an amount

determined by statute, or who are imprisoned, on parole, or on

supervised release as a result of certain types of violations of the

Controlled Substances Act, Bank Secrecy Act, and some state-level drug

laws.

13

Likewise, State may choose to refuse a passport to applicants

who are the subject of an outstanding local, state, or federal warrant of

arrest for a felony, or the subject of probation conditions or criminal court

orders that forbid the applicant from leaving the country and the violation

of which could result in the issuance of a federal arrest warrant.

14

During the adjudication process, passport specialists are to review

applications and results of checks against various databases to detect

fraud and suspicious activity, and for other purposes. Application data are

10

For example, see GAO-10-922T.

11

According to a State official, Passport Headquarters consists of eight offices, such as

the Office of Adjudication and the Office of Technical Operations.

12

A passport issued to an applicant who is under 16 years old is generally valid for 5

years.

13

22 U.S.C. § 2671(d), 42 U.S.C. § 652(k), and 22 U.S.C. § 2714.

14

22 C.F.R. § 51.60(b).

Passport Adjudication

Process

Page 10 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

entered into TDIS, State’s electronic processing system. TDIS

automatically checks applicants’ names against a number of sources,

including SSA’s death records and a database of warrants. For example,

TDIS automatically checks key identifying information of all passport

applicants against SSA’s full death file, as well as a database of felony

warrants for certain crimes. Passport specialists are to compare the

application to the information in TDIS to make sure it was entered

properly and to identify missing information.

Passport specialists are also to review the results of automatic checks

during a process State refers to as “the front-end” process of adjudication.

For instance, during this process, passport specialists are to determine

whether an applicant currently holds a passport, has a history of lost or

stolen passports, or has already submitted a passport application.

According to State officials, such checks are intended to facilitate the

identification of suspicious activity and prevent multiple passport

issuances to the same person. Passport specialists also are to consider

the results from facial recognition technology which is used to help

prevent the issuance of passports to individuals using false identities and

people who should be denied passports for other legal reasons, such as

terrorists in the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) terrorist

database.

15

In addition, passport specialists may employ commercial

databases and other tools during the adjudication process to assist in

confirming an applicant’s identity or citizenship.

15

In technical comments, State officials clarified that specialists do not deny passport

applications based solely on the results of facial recognition technology. According to

officials, facial recognition technology is one of many tools specialist use to determine

whether an application should be referred for further review and investigation. Officials

added that State does not deny passports to individuals identified in the FBI’s terrorist

database without additional review and investigation by the appropriate office.

Page 11 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

In April 2007, State and SSA signed an information-exchange agreement

that allows State to query SSA’s records for verifying applicants’ identities

and identifying deceased individuals. In accordance with this agreement,

State’s TDIS automatically queries SSA’s Enumeration Verification

System (EVS) to verify that a passport applicant’s SSN, name, and date

of birth match the records at SSA.

16

EVS includes a death indicator based

on SSA’s full death file of approximately 98 million records, which aids

State in identifying applicants using the identity of a deceased individual

to apply for a passport.

17

16

26 U.S.C. § 6039E requires passport applicants to provide an SSN, if they have one,

when applying for or renewing a passport. However, passports may be issued to

applicants who do not have an SSN.

In most cases, State’s controls will not flag an

applicant as deceased unless certain fields such as the SSN, name, and

date of birth all match the identifying information of a deceased individual.

According to State’s procedures, passport specialists must refer any

applications with a positive death indicator to State’s FPM for additional

review, since the match may indicate a case of stolen identity. The FPM

reviews all applications referred to it by passport specialists to determine

whether the identifying information on the passport application is in fact

associated with a deceased individual. The FPM can approve the

passport application once it has reviewed and resolved any indicators of

17

As GAO previously reported in May 2013, (GAO, Social Security Administration:

Preliminary Observations on the Death Master File, GAO-13-574T [Washington, D.C.:

May 8, 2013]), the Social Security Act places limitations on SSA’s sharing of state-

reported death information; SSA removes the state-reported records from the full death

file and provides the public death file, or public Death Master File, to the Department of

Commerce’s National Technical Information Service, which sells it through a subscription

service. Since October 2009, State used its subscription to the public death file, which

excludes state-reported death information and is available publicly to any interested party

for a fee. State officials noted in their technical comments that all applications are now

checked using SSA’s real-time verification system, and that State uses the public death

file in exceptional circumstances, such as when the real-time system is unavailable or for

postissuance audits. Unlike the public death file, the full death file contains all death

records, including state-reported death information, and is available to federal benefit-

paying agencies; however, State has access to certain data elements from the full death

file as a result of its information-exchange agreement with SSA.

Selected Controls for

Detecting Potentially

Fraudulent and High-Risk

Issuances

SSN Verification and Data

Checks for Deceased

Individuals

Page 12 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

potential fraud. See appendix III for additional details on State’s use of

SSA’s records for death checks.

In fiscal years 2009 and 2010, the years of passport issuances we

reviewed, State did not have access to federal and state prisoner

databases in order to check whether applicants’ identities matched those

of incarcerated individuals. Since then, State has taken steps to explore

access to such databases. For example, in June 2013, State entered into

a data-sharing agreement with the BOP in order to access federal

prisoner data. In addition, officials told us that in December 2013, State

completed the first phase of a pilot project using prisoner data from two

states, Florida and Rhode Island, to identify whether applicants are

fraudulently using identities of state prisoners. We provide additional

details on State’s initiatives to improve data checks for incarcerated

individuals in a subsequent section.

In 2002, the Marshals Service began transmitting certain warrant data to

State for use during the passport adjudication process. Since then, the

information State receives has changed to include additional warrants

from the FBI, as described in detail below. To help State determine

whether an applicant may have an active warrant for a felony charge,

TDIS automatically checks applicants’ identifying information in State’s

Consular Lookout and Support System (CLASS), a database that

maintains warrant data.

18

18

In addition to warrant data, CLASS contains other information, such as data from the

FBI’s Terrorist Screening Center database and information from the Department of Health

and Human Services about individuals delinquent on child support.

TDIS indicates a possible match if certain data

elements from the passport application, such as the name, SSN, date of

birth, place of birth, or gender, matches information in CLASS within

certain parameters. State’s policies require that passport specialists refer

likely matches in CLASS to State’s passport legal office. Officials said

paralegals in the passport legal office are to review the information and

contact the warrant issuer to confirm the identity of the subject in the

warrant against the passport applicant, verify that the warrant is active

and related to a felony charge, and further coordinate, as necessary. The

passport legal office may also use commercial databases, or photographs

obtained from the warrant issuer, to confirm applicants’ identities. In

technical comments, State officials clarified that the passport legal office

is authorized to deny the passport issuance when it determines, or is

informed by a competent authority, that the applicant is the subject of an

Data Checks for Incarcerated

Individuals

Data Checks for Individuals

with Active Warrants

Page 13 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

outstanding federal, state, or local warrant of arrest for a felony crime. In

addition, the passport legal office can authorize the passport issuance if it

determines, upon additional review, that there was not in fact a legitimate

match in CLASS. The legal office may approve an issuance in cases

where the warrant was closed, associated with a misdemeanor charge, or

for other reasons, such as a request by law enforcement agencies.

Of the combined total of approximately 28 million passport issuances we

reviewed from fiscal years 2009 and 2010, we found instances of

issuances to individuals who applied for passports using identifying

information of deceased or incarcerated individuals, as well as applicants

with active felony warrants. The total number of cases we identified

represented a small percentage of all issuances during the two fiscal

years, indicating that fraudulent or high-risk issuances were not

pervasive. We also determined that State’s data contained inaccurate

SSN information for thousands of passport recipients. Most of the

instances in which there was inaccurate SSN information appeared to be

applicant or State data-entry errors, rather than fraud. Since fiscal years

2009 and 2010, State has taken steps to improve its detection of passport

applicants using the identifying information of deceased or incarcerated

individuals. In addition, State modified its process for identifying

applicants with active warrants, and has expanded measures to verify

SSNs in real time.

Out of a combined total of approximately 28 million passport issuances

we reviewed from fiscal years 2009 and 2010, we identified 181

passports issued to individuals whose name and SSN both appeared in

SSA’s full death file, suggesting that the applicant may have

inappropriately used the identity of a deceased person.

19

19

These 181 passport issuances were associated with 167 unique individuals.

To ensure that

Examples of

Potentially Fraudulent

or High-Risk Passport

Issuances Found, but

Pervasive Fraud Not

Identified

Passport Issuances to

Applicants Associated with

Deceased Individuals,

Prisoners, and Individuals

with Active Warrants

Issuances to Applicants Using

Identifying Information of

Deceased Individuals

Page 14 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

our matches did not contain legitimate applicants who died shortly after

submitting their applications, we included only individuals who had died

more than 120 days before the passport issuance.

20

Figure 3: Description of Matching Analysis and Sample of Deceased Individuals

Figure 3 summarizes

our matching analysis and sample results.

a

It is not possible to determine from data matching alone whether the

passport issuance was appropriate or fraudulent without reviewing the

facts and circumstances for each individual case from the 181 passport

issuances. Thus, we randomly selected a nongeneralizable sample of 15

cases for additional analysis. For each case, we attempted to verify death

information from SSA’s full death file by obtaining a copy of the death

certificate and confirming that SSA’s most-current records listed the

individual as deceased. We also requested TECS travel data from

FinCEN and reviewed open-source information to search for additional

fraud indicators. The following information provides additional details on

the 15 cases.

These totals are solely based on the matching criteria described. We conducted additional reviews to

verify data for the sample items in the next column. We did not verify that all issuances from our

matching analysis were actual cases of fraud or issuances to individuals with active warrants. Rather,

we selected samples for additional review, and referred all matches to State for further investigation.

• In one case, the applicant applied for and received an expedited

passport by mail in January 2009 using the SSN, name, and date of

birth of a deceased individual. The SSA’s full death file and the death

certificate indicated that the purported applicant had died in May

20

We selected 120 days after death to allow for approximately 60 days of passport

application processing time and 60 days of lag time in reporting an individual’s death to

SSA for inclusion in the full death file.

Page 15 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

2008. According to TECS travel data, the passport was used in June

2009 to fly to the United States from Mexico and had not been used

again as of June 2013. As a result of information we provided, State

reviewed this case in 2013 and determined that the applicant

appeared to be an imposter. State officials noted that the application

should have been referred to the FPM during adjudication, because it

contained multiple fraud indicators. State officials said this case

should be referred to the Bureau of Diplomatic Security (DS) for

further investigation.

• In another case, the applicant’s passport issuance was delayed by

more than a year because her name mistakenly appeared in SSA’s

full death file. In our May 2013 testimony, we found that SSA’s data

contained a small number of inaccurate records, and SSA has stated,

in rare instances, it is possible for the records of a person who is not

deceased to be included erroneously in the death file.

21

• In 4 of the 15 cases, the applicant used a similar name to, as well as

the same SSN as, a deceased individual. For each of the four cases,

we verified the death information in SSA’s full death file by obtaining a

copy of the deceased person’s death certificate. However, State

officials said fraud could likely be ruled out in all four cases for various

reasons, such as the inadvertent use of an incorrect SSN.

Situations

where a living individual is inappropriately listed as deceased in SSA’s

records can create a hardship for the person who has been falsely

identified as deceased. This case highlights one of the challenges

State encounters when querying SSA’s full death file, and illustrates

why State reviews applicants with death indicators on a case-by-case

basis.

• In 9 of the 15 cases, we could not verify the death of the applicants

because we were unable to identify the state in which the individual’s

death was recorded (possibly because the applicant was not

deceased) or because state officials would not or could not provide

the death certificate to us. State’s subsequent review of these cases

indicated that fraud could likely be ruled out in four cases, and that

five of the cases should be referred to DS for further investigation.

As of May 2014, we have referred all 181 passport issuances we

identified from our matching analysis using SSA’s full death file, including

21

GAO-13-574T.

Page 16 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

the 15 cases we examined in more detail, to State for further review and

investigation.

Out of the combined total of approximately 28 million passport issuances

we reviewed from fiscal years 2009 and 2010, we identified 68 issuances

to individuals who used an SSN, name, and in some cases, date of birth

of a state prisoner on their passport application.

22

Without reviewing the

facts and circumstances for each case, it is not possible on the basis of

data matching alone to determine the extent to which these instances

represent fraudulent issuances. Thus, from the group of individuals

related to the 68 issuances, we selected 14 cases for further review.

23

Figure 4: Summary of Matching Analysis and Sample of State Prisoners

For

each sample case, we obtained additional documentation from state

departments of corrections to verify key data fields for these passport

recipients. Figure 4 summarizes our matching analysis and sample

results.

a

22

In our data matching, we used state prisoner data from 11 states including Alabama,

Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Texas, and

Virginia. Three of these state prison databases did not have any valid matches to the

passport data. In addition, data from three states with matches did not include dates of

birth, and therefore records in these databases matched to State’s passport data based

on SSN and name only.

These totals are solely based on the matching criteria described. We conducted additional reviews to

verify data for the sample items in the next column. We did not verify that all issuances from our

matching analysis were actual cases of fraud or issuances to individuals with active warrants. Rather,

we selected samples for additional review, and referred all matches to State for further investigation.

23

The 68 passport issuances were associated with 61 unique individuals. In addition, our

review indicated that some matches may reflect situations in which a prisoner stole the

applicant’s identity prior to incarceration, resulting in matches to State’s passport data that

do not represent fraud.

Issuances to Applicants Using

the Identifying Information of

State and Federal Prisoners

Page 17 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

b

Our review indicated that some matches may be a result of identity theft perpetrated by the state

prisoner, prior to incarceration, and not by the passport applicant. In addition, data from three states

with matches did not include dates of birth, and therefore records in these databases matched to

State’s passport data based on SSN and name only.

c

From our nongeneralizable sample of 14 cases, we identified seven

passport applicants who may have fraudulently used the identities of state

prisoners, since the incarcerated individuals could not have physically

appeared at a passport facility to submit their applications.

We selected a nongeneralizable sample of up to two prisoners incarcerated in each of the states we

reviewed for a total of 14 cases from eight different states.

24

We could not conclusively determine that all our sample cases or

matches represented passport fraud, because for instance, it is possible

that the state prisoner may have stolen the identity of the applicant prior

to incarceration. For example, we identified two cases involving data from

the same prison facility in which the prisoner had an alias name, in

addition to an SSN and date of birth, that matched the information of the

passport applicant. We provided information on all our matches, including

the 14 state prisoner cases in our sample, to State for review. According

to officials, State’s review of these cases included, but was not limited to,

an assessment of fraud indicators in the passport applications, and

review of the applicants’ information in commercial and internal

databases. State determined that fraud could likely be ruled out in eight

cases. Officials initially said they should refer the remaining six cases to

DS for further investigation. In their technical comments on a draft of this

report, State officials said they conducted a second review of the six

remaining cases and determined that two individuals used their true

identities on their passport applications, and they ultimately referred four

cases to DS for investigation.

The seven

remaining cases in our state prisoner sample of 14 individuals were either

not incarcerated at the time of application submission, applied for

passports using mail-in applications, or represented possible identity theft

by the prisoner prior to incarceration. Federal regulations do not prohibit

State from issuing passports to prisoners; however, according to officials,

State’s policy is to deny passport issuances to individuals who are

incarcerated at the time of application submission.

24

These seven individuals applied for a passport using a DS-11 application, which must

be submitted in person at an acceptance facility or passport agency.

Page 18 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Of the four cases in our state prisoner sample that State officials referred

to DS, we identified three instances where the passport was used to

cross an international border during the prisoners’ periods of

incarceration. These cases highlighted the active use of passports

obtained by potentially fraudulent means. We verified this travel activity

by comparing the names, dates of birth, and passport numbers in State’s

passport data for these cases with TECS travel data provided by FinCEN.

The TECS travel log for the three cases showed that the individuals used

the passports for international travel at least once during the prisoners’

periods of incarceration. In one case, an individual used the passport

obtained by potentially fraudulent means to cross the U.S.-Mexico border

more than 300 times.

In addition to our analysis of state prisoners, we also identified 206

passport issuances to individuals who used an SSN, name, and date of

birth in their applications that matched identifying information in the BOP’s

federal prisoner data. However, the data we received included individuals

residing in halfway houses. Unless otherwise stated in the conditions of

release for parole, passport issuances to individuals living in halfway

houses are legally permissible. Since we focused our in-depth analysis on

a nongeneralizable sample of 15 cases, we did not determine the extent

to which the 206 cases represented individuals in federal prison facilities

as opposed to halfway houses. Figure 5 summarizes our matching

analysis and sample of 15 cases.

Figure 5: Summary of Matching Analysis and Sample of Federal Prisoners

a

These totals are solely based on the matching criteria described. We conducted additional reviews to

verify data for the sample items in the next column. We did not verify that all issuances from our

matching analysis were actual cases of fraud or issuances to individuals with active warrants. Rather,

we selected samples for additional review, and referred all matches to State for further investigation.

b

This number includes passport issuances to people residing in halfway houses, and therefore may

not represent issuances to individuals using the identities of federal prisoners to apply for a passport.

Page 19 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

From our sample of 15 cases, we did not identify any individuals who

applied for a passport using the identity of a federal prisoner in their

passport application. We determined that at least 9 of the 15 individuals

were living in BOP halfway houses when the passport application was

submitted. Moreover, we did not find any indications of identity theft. The

other six individuals were either not in a halfway house at the time of

application submission, or we were unable to determine, on the basis of

the information provided, their location after they were released from a

federal prison facility.

25

In fiscal years 2009 and 2010, officials said State did not have access to

federal and state prisoner databases in order to check whether

applicants’ identities matched those of incarcerated individuals. In June

2013, State entered into a data-sharing agreement with the BOP that will

allow it to access federal prisoner data, including information about

individuals incarcerated in federal facilities or halfway houses. In addition,

State obtained data-sharing agreements with two individual state

departments of corrections, Florida and Rhode Island, as part of a pilot

project to identify whether applicants fraudulently used the identities of

state prisoners. State officials said these states represent different

geographical regions and a large and small inmate population, and both

had technical capabilities to transfer data efficiently and securely to State

for adjudication purposes. Officials said in their technical comments that

State completed the first phase of the pilot project in December 2013.

This phase included the development of search criteria for detecting the

fraudulent use of prisoners’ identities. According to officials, State referred

three potential fraud cases to DS for further investigation as a result of

this effort. Officials also reported in their technical comments that State

plans to acquire prisoner data from other states, and that it is developing

best practices for obtaining such data. In addition, officials noted that

State is in the early stages of planning a second phase of the pilot project.

However, the documentation for these six

individuals indicated that they were not incarcerated when the application

was submitted.

State officials highlighted various challenges with respect to using

prisoner data during adjudication, including technical requirements and

issues related to data transmission, as well as potential legal limitations.

25

Of these six individuals, one was incarcerated in a federal prison facility at the time of

passport issuance. However, the individual applied for the passport prior to being in

federal custody, and was subsequently issued a passport once his sentence began.

Page 20 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

For example, according to BOP officials, State and the BOP will have to

develop a technical infrastructure to facilitate sharing of federal prisoner

data, which officials expected to occur no later than the end of fiscal year

2014. Similarly, with respect to state prisoner data, State officials noted

that data from state departments of corrections would need to be

automatically transmitted to allow for the updating of information on a

consistent basis. In technical comments, State officials clarified that they

would prefer to receive data from individual state departments of

corrections on a real-time basis; however, the frequency with which State

receives these data is not a factor in determining whether State enters

into a data-sharing agreement with a department of corrections. State

officials also highlighted issues regarding the compatibility of systems

from various states, as well as concerns about poor data that could lead

to false matches and delays in processing passport applications.

Moreover, State officials told us legal limitations may prevent the transfer

of state-level inmate data; however, State did not report having such

challenges working with Florida and Rhode Island during its pilot project.

Out of a combined total of approximately 28 million passport issuances

we reviewed from fiscal years 2009 and 2010, we identified 486

issuances to individuals using the SSN, name or alias, and date of birth of

people with active warrants on their passport applications.

26

We could not

determine from matching analysis alone whether all warrants were

associated with felonies, but our analysis excluded warrants with a

description of either a “traffic crime” or “misdemeanor” in data provided by

the Marshals Service (see app. IV for additional details). The type of

warrant data State has received for detecting active felony warrants

through CLASS has changed over time. In 2002, the Marshals Service

began providing State with certain warrant information in CLASS. These

only included Class 1 warrants, which is a designation for warrants the

Marshals Service enters and maintains in the National Crime Information

Center (NCIC) database, a criminal database that provides the warrant

data to CLASS.

27

26

These issuances include individuals whose SSN, partial name (or alias), and date of

birth in warrant data provided by the Marshals Service matched information in State’s

passport data. In addition, these 486 passport issuances were associated with 442 unique

individuals with a total of 564 open warrants.

According to State officials, the FBI began providing

State with federal felony warrants in 2005 for use during the adjudication

27

The NCIC database is an electronic repository of data on crimes and criminals of

nationwide interest and a locator file for missing and unidentified persons.

Issuances to Individuals with

Active Warrants

Page 21 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

process. In late July 2009, officials said State began receiving state and

local warrants from the FBI for crimes of varying degrees of severity,

including misdemeanors, serious felonies, and nonserious felonies.

28

28

FBI officials told us the bureau completed modifications of its warrant data for State in

August 2007 to include not only federal warrants, but also state and local warrants.

According to State officials, it would have been infeasible for State to receive or use state

or local warrant data in 2007, given the technical and operational requirements for

preparing CLASS, guidance to passport specialists, and instructions to offices that assist

in the passport adjudication process. Officials added that State’s regulatory authority to

deny or revoke passports on the basis of an outstanding state or local felony warrant was

not effective until February 2008. Moreover, the Memorandum of Understanding between

the FBI and State for sharing state and local warrants was not signed by both parties until

January 2009.

According to State officials, the high volume of warrant cases was

unmanageable and State had no authority to take action on misdemeanor

warrants. Thus, in November 2010, State officials said they updated

CLASS so that it included only state or local warrants connected to more-

serious felonies they selected. Officials also said CLASS is updated daily

with information provided by the Marshals Service and the FBI, and

currently contains information for federal, state, and local felony warrants

related to State’s selected felony charges. Figure 6 illustrates the

evolution in State’s data checks for warrants.

Page 22 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Figure 6: Timeline Showing When the Department of State (State) Began Checking for Federal, State, and Local Warrants

a

“Class 1” is a designation of the Marshals Service for warrants it enters and is responsible for in the

NCIC database, a criminal database that sources the warrant data in Consular Lookout and Support

System (CLASS).

b

From the population of 486 issuances with active warrants that we

identified through matching, we randomly selected a nongeneralizable

sample of 15 individuals for additional analysis. Figure 7 summarizes our

matching analysis and sample results.

According to officials, in November 2010, State selected certain felonies for inclusion in State’s

CLASS in response to a high volume of state and local warrants it received in July 2009, which also

included warrants for misdemeanors.

Page 23 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Figure 7: Summary of Matching Analysis and Sample of Applicants with Active Warrants

a

These totals are solely based on the matching criteria described. We conducted additional reviews to

verify data for the sample items in the next column. We did not verify that all issuances from our

matching analysis were actual cases of fraud or issuances to individuals with active warrants. Rather,

we selected samples for additional review, and referred all matches to State for further investigation.

b

According to the Marshals Service, all 15 of the individuals in our

nongeneralizable sample had warrants related to felony charges, 3 of

which the Marshals Service was responsible for executing. Fugitives with

felony warrants may pose a risk to public safety, and passports could help

them evade capture by law enforcement agencies. State may choose to

refuse a passport to applicants who are the subject of an outstanding

felony warrant. In our analysis of the 15 cases, we took into account the

evolution in State’s controls. Figure 8 summarizes our review of the cases

in our sample.

These 486 passport issuances were associated with 442 unique individuals with a total of 564 open

warrants. Beyond our sample items, we did not confirm whether the warrant was associated with a

felony charge. However, these records excluded all warrants with a description of either a “traffic

crime” or “misdemeanor.”

Page 24 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Figure 8: Summary of Whether State Identified the Warrants in Our Sample Population

a

According to officials, State received a notice from the relevant U.S. District Court regarding this

individual that indicated the court order for the person had ceased and the individual was sentenced

to probation. As a result, State officials said the warrant for this individual was not included in the

Consular Lookout and Support System (CLASS) for State’s warrant check.

b

Upon further review of our original sample of 15 cases, we identified one individual who had a state

or local warrant that was not issued until after the applicant applied for his passport. In addition, our

review of court documents for another case indicated the individual was unlikely to have been a

fugitive when applying for the passport, since he was arrested and faced criminal charges after the

warrant was issued, but about a decade before submitting the application. As a result, we did not

further review these cases as part of our sample.

Page 25 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Among the 13 applicants we reviewed in detail, we found five cases with

warrants that State identified during the adjudication process. For

instance, after detecting the warrant in one case, State’s passport legal

office ultimately determined the passport applicant was a victim of identity

theft and was not the subject of the warrant. In another case, State

identified a warrant at the state or local level for an applicant who applied

for a passport at a time when State’s controls had begun checking for

such warrants. In this case, State’s passport legal office authorized the

passport issuance to the individual after concluding the associated charge

was for a misdemeanor crime, as opposed to a felony offense. We also

identified five cases where the applicants had outstanding state or local

felony warrants on the application date, and State’s CLASS did not have

data for such warrants when the individuals applied.

29

In the other 3 of the

13 sample cases we reviewed, we found no indications that State was

aware of or alerted to the individuals’ warrants at the time they applied for

passports, even though it appeared that CLASS should have included the

warrant data.

30

We referred all passport issuances we identified from our

matching analysis, including our sample cases, to State for further review

and investigation.

29

For one of these cases, State provided additional details on a subsequent passport

issuance. Specifically, State highlighted a case of passport fraud involving an individual in

our sample that occurred after the period of passport issuances we reviewed from fiscal

years 2009 and 2010.

30

Officials of the Marshals Service told us there can be delays between the date a warrant

is issued and the date a law enforcement agency validates it in the NCIC database.

Alternatively, the officials said, law enforcement agencies may elect not to enter the

warrant into a federal database at all. In such circumstances, State would not be alerted to

the warrant, regardless of whether it was federal, state, or local, because CLASS would

not contain information about it for use during the passport adjudication process.

Page 26 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Out of the combined total of approximately 28 million passport issuances

we reviewed from fiscal years 2009 and 2010, we found 13,470 passport

issuances to individuals who submitted an SSN associated with a

deceased individual,

31

but where the name used in the passport

application did not match the name of the deceased individual.

32

Figure 9: Summary of Matching Analysis and Sample of Deceased-SSN Errors

As we

previously noted, we analyzed these cases to determine whether the

applicant provided the correct SSN and State recorded it incorrectly, or

whether the applicant provided the wrong SSN and State recorded the

incorrect SSN its system. Specifically, from this population, we selected a

stratified random sample that consisted of 140 passport issuances,

evenly divided between fiscal years 2009 and 2010 (see fig. 9). We refer

to these cases below as deceased-SSN errors.

a

These totals are solely based on the matching criteria described. We conducted additional reviews to

verify data for the sample items in the next column. We did not verify that all issuances from our

matching analysis were actual cases of fraud or issuances to individuals with active warrants. Rather,

we selected samples for additional review, and referred all matches to State for further investigation.

b

The generalizable stratified random sample of 140 passport issuances included 70 passport

issuances from both fiscal years 2009 and 2010.

31

State may issue multiple passports to the same individual, such as when the applicant

applies for both a passport book and a passport card. These 13,470 passport issuances

were associated with 12,781 unique individuals.

32

We also found 181 passport issuances where both the applicant’s name and SSN

matched the SSN and name of a deceased individual. These issuances are described in

detail in the previous section under the subheading “Issuances to Applicants Using

Identifying Information of Deceased Individuals.”

State’s Records Contained

Erroneous SSNs for

Thousands of Passport

Issuances as a Result of

Applicant or State Data-

Entry Error

Page 27 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

We estimated that approximately 50 percent of the 13,470 cases with

deceased-SSN errors were instances where the applicant provided an

SSN that did not belong to him or her.

33

33

From 13,470 passport records with names that did not match the corresponding record

in the SSA full death file, we selected a stratified random sample of 140 passport

issuances. All estimates from this sample have a margin of error of +/-9 percentage points

or fewer unless otherwise noted. See app. I for more details.

We did not identify any other

evidence of potential fraud in this group of cases, which suggests that

applicants may have made mistakes in filling out the passport application.

We estimated that in approximately 44 percent of the 13,470 cases with

deceased-SSN errors applicants provided the correct SSNs, but State

entered them incorrectly into TDIS. State officials could not provide an

explanation for the errors related to these cases, which included

applications with handwritten SSNs that were difficult to read, as well as

typed SSNs. The remaining 6 percent of cases did not fall into either of

these categories. Such cases included instances where the applicant did

not provide an SSN, or where we were unable to ascertain the applicant’s

actual SSN. Figure 10 summarizes the issuances we reviewed involving

deceased-SSN errors.

Page 28 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

Figure 10: Estimated Percentage of Causes of Incorrect SSNs Associated with

Deceased Individuals in State’s Passport Data

Notes: All percentage estimates in figure 10 are generalized to the population of 13,470 cases with

deceased-SSN errors. All estimates in figure 3 have a margin of error of +/-9 percentage points or

fewer at the 95 percent confidence level.

a

In addition to deceased-SSN errors, we also found 24,278 issuances

during fiscal years 2009 and 2010 to individuals who applied for a

passport using a likely invalid SSN that SSA has never issued.

Records that did not fall into any of the two categories above were classified as “other.” Examples

include instances where the applicant did not provide an SSN, or where GAO was unable to ascertain

the applicant’s actual SSN.

34

34

State may issue multiple passports to the same individual, such as when the applicant

applies for both a passport book and a passport card. These 24,278 passport issuances

were associated with 22,543 unique SSNs. In some cases, more than one individual used

the same likely invalid SSN to apply for a passport.

For

example, SSA has never issued the SSN “999-99-9999,” so we would

Page 29 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

have included an applicant who used that SSN in this population.

35

We

randomly selected a nongeneralizable sample of 15 cases from the

population of unique, likely invalid SSNs for additional review (see fig.

11). In seven cases, State improperly recorded the applicants’ SSNs in

TDIS. In six cases, the applicant provided an incorrect SSN, five of which

were close to the applicant’s actual SSN.

36

Figure 11: Summary of Analysis and Invalid Social Security Number Sample

We did not determine the

cause of the invalid SSNs in the remaining two cases, because they

involved minors for whom we could not ascertain the passport recipient’s

actual SSNs.

a

State officials were unable to identify the specific reason for the

deceased-SSN errors or likely invalid SSNs we identified, but the agency

said it has taken actions to capture correct SSN information more

consistently. For example, since January 2010, State’s management has

issued memorandums clarifying the policies and procedures for capturing

These totals are solely based on the matching criteria described. We conducted additional reviews to

verify data for the sample items in the next column. We did not verify that all issuances from our

matching analysis were actual cases of fraud or issuances to individuals with active warrants. Rather,

we selected samples for additional review, and referred all matches to State for further investigation.

35

26 U.S.C. § 6039E requires passport applicants to provide an SSN, if they have one,

when applying for or renewing a passport. When an applicant has not been issued an

SSN, State requests applicants to enter all zeroes in the SSN field on the passport

application. We therefore excluded SSNs with all zeroes from our analysis of invalid

SSNs. However, we included in our analysis other single-character SSNs, such as “999-

99-9999.” While these SSNs are invalid, they may reflect an attempt by applicants without

SSNs to follow State’s guidance.

36

We defined a “close” SSN as one where at least six digits matched the applicant’s actual

SSN. SSNs that were not close were defined as those with more than three digits that did

not match the applicant’s actual SSN.

Page 30 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

and correcting applicant SSN information. In addition, in September 2011,

State signed an information-exchange agreement with SSA to implement

a real-time verification process through a secure online system. As of

June 2013, State officials said all 28 domestic agencies and centers were

able to verify SSNs in real time. We have not assessed these measures’

effects on reducing SSN errors, but among the issuances we reviewed,

SSN errors fell from about 24,762 in fiscal year 2009 to approximately

12,986 in fiscal year 2010.

37

We provided a draft of this report to State and the Department of Justice

for comment. State provided technical comments, which we incorporated

into the report, as appropriate. The Department of Justice did not have

any comments.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of

this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the

report date. At that time, we will send copies to interested congressional

committees, the Secretary of State, and the Attorney General. In addition,

the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at

http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact

me at (202) 512-6722 or lor[email protected]. Contact points for our Offices of

Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page

of this report. GAO staff who made major contributions to this report are

listed in appendix V.

Stephen M. Lord

Managing Director

Forensic Audits and Investigative Service

37

These incorrect SSNs only include SSNs associated with a deceased individual, or

SSNs that we could identify as having never been issued. They do not include legitimately

issued SSNs listed incorrectly in State’s data that do not belong to a deceased individual,

and therefore the count may be understated.

Agency Comments

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and

Methodology

Page 31 GAO-14-222 Department of State Passport Services

You asked that we assess potential fraud in the Department of State’s

(State) passport program. This report examines potentially fraudulent or

high-risk issuances among passports issued during fiscal years 2009 and

2010.

1

To examine potentially fraudulent and high-risk passport issuances in

fiscal years 2009 and 2010,

2

we matched State’s passport-issuance data

for approximately 28 million passport issuances to databases containing

information about individuals who were (1) deceased, (2) incarcerated in

a state prison facility, (3) in the custody of the federal Bureau of Prisons

(BOP), or (4) the subject of an active warrant at the time of the passport

issuance.

3

1

For purposes of this report, potentially fraudulent passport issuances are those that

involve an applicant using someone else’s identity to apply for and receive a passport. We