1

Obstructed View:

New York State Aorney General

Eric T. Schneiderman

From the Office of:

What’s Blocking New Yorkers from Geng Tickets

SolD oUt AgAIn|

CAPTCHA

Type the two words:

1

This report was a collaborave eort prepared by the Bureau of Internet and Technology

and the Research Department, with special thanks to Assistant Aorneys General Jordan

Adler, Noah Stein, Aaron Chase, and Lydia Reynolds; Director of Special Projects Vanessa Ip;

Researcher John Ferrara; Director of Research and Analycs Lacey Keller; Bureau of Internet and

Technology Chief Kathleen McGee; Chief Economist Guy Ben-Ishai; Senior Enforcement Counsel

and Special Advisor Tim Wu; and Execuve Deputy Aorney General Karla G. Sanchez.

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Execuve Summary ....................................................................... 3

The History of, and Policy Behind, New York’s Tickeng Laws ....... 7

Current Law ................................................................................... 9

Who’s Who in the Tickeng Industry ........................................... 10

Findings ....................................................................................... 11

A. The General Public Loses Out on Tickets to

Insiders and Brokers .................................................................... 11

1. The Majority of Tickets for Popular Concerts Are Not Reserved

For the General Public .......................................................................... 11

2. Brokers & Bots Buy Tickets in Bulk, Further Crowding Out Fans ...... 15

a. Ticket Bots Amass Hundreds or Thousands of Tickets in an Instant ....... 15

b. Even without Bots, Brokers Use Industry Knowledge and Relaonships

to Gain an Edge Over Fans ...................................................................... 21

c. Ticket Limits Are Not Regularly Enforced ................................................ 22

d. Brokers, With and Without Bots, Buy Up Many

Tickets to New York Events ..................................................................... 23

e. Brokers Sell Tickets at Substanal Markups ............................................ 25

f. Speculave Tickets Increase Confusion and Risk for Fans ........................ 26

g. The Market Structure Is Atypical ............................................................. 27

B. High Fees for Unclear Purposes Raise Concerns ......................... 28

1. Fees are Charged by Ticket Vendors and Venues ............................. 29

2. Event Ticket Fees are Higher than Most Online Vendors ................. 31

C. Restraints of Trade in Tickeng ................................................... 32

1. Seng of Ticket Resale Price Floors ................................................. 32

2. Pracces That Impede Consumer Access to

Alternave or “Unocial”Ticket Resale Plaorms................................ 33

Recommendaons ....................................................................... 34

Appendix – Methodology for NYAG Analyses ...............................38

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The New York Aorney General (“NYAG”) regularly receives complaints from New Yorkers

frustrated by their inability to purchase ckets to concerts and other events that appear to sell

out within moments of the ckets’ release. These consumers wonder how the same ckets

can then appear moments later on StubHub or another cket resale site, available for resale at

substanal markups. In response to these complaints, NYAG has been invesgang the enre

industry and the process by which event ckets are distributed – from the moment a venue

is booked through the sale of ckets to the public. This Report outlines the ndings of our

invesgaon.

More than 15 years ago, NYAG issued a landmark report on what it called “New York’s largely

underground and unexamined cket distribuon system.” The report announced that it was

a system that provides “access to quality seang on the basis of bribes and corrupon at the

expense of fans.”

Since that report was wrien broad changes in the technology of ckeng and an overhaul of

New York’s ckeng laws have completely transformed the landscape, in ways both good and

bad. Following the repeal of New York’s “an-scalping laws” in 2007, the once underground

cket resale economy moved parally above ground. This change has produced some benets:

online marketplaces have replaced waing in long lines, the growth of cket resale plaorms

has somemes made it easier to sell unwanted ckets, and the last minute-minded can aend

shows without interacng with potenally dishonest street scalpers.

Yet many of the problems described in 1999

have persisted and, in some cases, have grown

worse. Whereas in many areas of the economy

the arrival of the Internet and online sales has

yielded lower prices and greater transparency,

event ckeng is the great excepon. The

complaints NYAG receives from consumers

concerning ckeng commonly cite “price

gouging,” “scalping,” “outrageous fees” and

“immediate sell-outs.” As one cizen wrote,

in a typical complaint: “The average fan has

no chance to buy ckets at face value … this

is a disgrace.” Many performers voice similar

frustraons.

1

The problem is not simply that demand for prime

seats exceeds supply, especially for the most in-

demand events. Tickeng, to put it bluntly, is a

xed game. Consider, for example, that on December 8, 2014, when ckets rst

went on sale for a tour by the rock band U2, a single broker purchased 1,012 ckets to one show

at Madison Square Garden in a single minute, despite the cket vendor’s claim of a “4 cket

1. See, e.g., Mark Savage, “Sir Elton John: Secondary ticket prices ‘disgraceful’,”BBC News (Dec. 16, 2015),

available at

http://www.

bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-35091230; Patrick Doyle, “Eric Church on Scalpers, Bro-Country and Blake Shelton Scandal,”

Rolling Stone (June 11, 2014),

available at

http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/eric-church-on-scalpers-bro-country-and-

blake-shelton-scandal-20140611.

“I think it’s extoronate

and I think it’s disgraceful.”

- Sir Elton John, referring to inated

secondary sales

“It’s a systemac problem

with music ...”

- Eric Church, referring to scalpers

4

limit.” By the end of that day, the same broker and one other had together amassed more than

15,000 ckets to U2’s shows across North America.

Consider that brokers somemes resell ckets at margins that are over 1,000% of face value.

Consider further that added fees on ckets regularly reach over 21% of the face price of ckets

and, in some extreme cases, are actually more than the price of the cket. Even those who

intend their events to be free, like Pope Francis, nd their good intent defeated by those who

resell ckets for hundreds or even thousands of dollars.

Findings

A. The General Public Loses Out on Tickets to Insiders and Brokers.

New Yorkers keep asking the same queson: why is it so hard to buy a cket at face value?

1. Holds & Pre-Sales Reduce the Number of Tickets Reserved for the General Public.

Our invesgaon found that the majority of ckets for the most popular concerts are not reserved

for the general public at least in the rst instance. Rather, before a member of the public can buy

a single cket for a major entertainment event, over half of the available ckets are either put on

“hold” and reserved for a variety of industry insiders including the venues, arsts or promoters,

or are reserved for “pre-sale” events and made available to non-public groups, such as those

who carry parcular credit cards.

2. Brokers Use Insider Knowledge and Oen Illegal Ticket Bots to Edge Out Fans.

When ckets are released, brokers buy up as many desirable ckets as possible and resell them

at a markup, oen earning individual brokerages millions of dollars per year. To ensure they get

the ckets in volume, many brokers illegally rely on special soware – known as Ticket Bots – to

purchase ckets at high speeds. As the New York Times reported, Ticketmaster has esmated

that “60 percent of the most desirable ckets for some shows” that are put up for sale are

purchased by Bots.

2

Our research conrms that at least tens of thousands of ckets per year are

being acquired using this illegal soware.

Brokers then mark up the price of those ckets – by an esmated 49% on average, but somemes

by more than 1,000% – yielding easy prots. In at least one circumstance, a cket was resold at

7,000% of face value. Finally, some brokers sell “speculave ckets,” meaning they sell ckets

that they do not have but expect to be able to purchase aer locking in a buyer. Speculave

ckets are a risk for consumers and also drive up prices even before ckets are released.

NYAG’s invesgaon idened those brokers re-selling the most ckets for New York events.

Nearly all were unlicensed, and several employed illegal Ticket Bots to buy ckets. A number of

specic invesgaons and enforcement acons are in process.

2. Ben Sisario, “Concert Industry Struggles With ‘Bots’ That Siphon O Tickets,” N.Y. Times (May 26, 2013),

available at

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/27/business/media/bots-that-siphon-o-tickets-frustrate-concert-promoters.html

5

B. High Fees for Unclear Purposes Raise Concerns.

Another common complaint concerns the unclear and unreasonable “service fees” added to the

face value of ckets, which are generally set by venue operators and cket vendors. New York

law prohibits these pares from adding fees to the prices of ckets unless they are connected

to the provision of a “special service” and are “reasonable.” Our examinaon of cket fees

set by 150 venues in New York raises concerns, revealing that unclear “convenience charges,”

“service fees,” and “processing fees” somemes reach outlandish levels, either as a percentage

of the cket’s face value or in absolute dollar terms. On average, New York venues and their

ckeng vendors charge fees averaging 21% of face values, which exceeds what other online

sellers charge. Moreover, we found fees as high as $42 aached to a cket to see Professional

Bull Riding at Madison Square Garden and $28 to see Janet Jackson at Jones Beach Theater.

C. Restraints of Trade Exist.

NYAG is concerned by the growing imposion of resale price oors (i.e. “no sales below list

price”), along with eorts to mandate that ckets be sold on a single “walled garden” market, as

opposed to consumers having the opon of buying ckets from dierent resale plaorms. We

are also interested in the degree to which excessive service charges may constute evidence of

abuse of monopoly power, especially as they relate to the resale of sports ckets.

Recommendaons

In 1999, NYAG found that, despite long-standing regulaon, the law “has not succeeded in

eliminang the abuse it was intended to address.” That remains true today, and New York

remains in need of greater protecons for the buying public. We therefore oer several

recommendaons:

A. Ticket Resale Plaorms Must Ensure Brokers Comply With the Law.

Ticket resale plaorms are in the best posion to ensure that their broker customers follow the

law, and they must take meaningful steps to do so. Specically, these plaorms should require

that brokers provide their New York license numbers as a condion of using the resale plaorm,

and disclose to potenal customers the face value of ckets they are oering for sale, as already

required by New York law.

B. Industry Players Must Increase Transparency Regarding

Ticket Allocaons and Limits.

The industry must provide greater transparency into the allocaon of ckets, to increase

accountability and enable the public to make informed choices. Promoters of events, who

know the number of seats being held, should provide that informaon to cket vendors, such

as Ticketmaster, to make available to the public. In addion, wherever cket vendors claim that

cket limits are enforced, they should enforce those limits as a maer of course on a per-person

basis. If such limits are not actually being enforced, cket vendors must make that clear.

6

C. Ticket Vendors Must Address the Bot Epidemic.

Bot use is a major reason why New Yorkers cannot get ckets at face value. While the industry

works on long-term technological soluons to this problem, steps can be taken to reduce Bot

use in the near-term. NYAG has contacted Ticketmaster and another major cket vendor, AXS,

to discuss concrete reforms, such as preempve enforcement of cket limits, analyzing purchase

data to idenfy ongoing Bot operaons for prosecuon, and invesgang resellers of large

volumes of ckets to popular shows, among others.

D. The Legislature Should Act.

While there is no reason the industry should wait for legislave acon to implement the reforms

outlined above, the Legislature should act to ensure that reform is meaningful and lasng.

Specically:

i. Mandate the industry reforms outlined above.

ii. End the ban on non-transferrable paperless ckets.

A soluon that most industry parcipants agree is eecve at reducing broker acvity is

the use of non-transferrable “paperless ckets.” Unlike paper ckets and electronic ckets

that are freely transferrable from the buyer to another person, non-transferrable paperless

ckets require an event aendee to present the credit card that was used to purchase the

cket. As a result, the inial purchaser typically must be present to use the cket. State

law creates a

de facto

ban on these paperless ckets, but this rule makes New York an

outlier – ours is the only state that bans the pracce – and this ban should be repealed.

iii. Impose criminal penales for Bot use.

Given that cket resellers are making considered business decisions when they deploy

Bots to acquire massive amounts of ckets near-instantaneously, the prospect of criminal

prosecuon may well have a deterrent eect on this conduct.

iv. Cap permissible resale markups.

Unl 2007, New York capped the markup resellers could charge, and the State removed

that cap in hopes of beneng consumers. Unfortunately, compeon-driven savings

intended to benet fans have instead been converted to prots for a handful of savvy

middlemen using mulple employees or computers, or illegal Bots. New York should

reinstute a reasonable limit on resale markups.

7

THE HISTORY OF, AND POLICY BEHIND,

NEW YORK’S TICKETING LAWS

New York’s approach to ckeng has undergone dramac changes over the last een years.

Understanding both the history and the policy goals of previous and current ckeng legislaon

is important to all that follows.

3

1920 – 2007: The “An-Scalping” Era.

“The greatest evil that theatergoers in this city have to contend with is the cket speculator,”

wrote a New York City magistrate in 1901. “They are praccally highwaymen and hold up

everybody that goes to a place of amusement.”

4

As the quote suggests, the resale of ckets for

prot has long been considered an aggravaon in this State. In 1922, Governor Nathan Miller

declared the need for acon to combat what he called “gross proteering” by “cket scalpers.”

He signed a law, widely described as an “an-scalping law,” that began the State’s regulaon of

cket sales for major events. It originally regulated “boxing and wrestling, relang to ckets to

places of entertainment,” and capped the price of resale ckets at two dollars above face value.

5

The law maintained its basic character for seventy years, broadening in scope, and adding various

provisions to ban bribes paid to venues by brokers for ckets (known as “ice”). Eventually, the

two-dollar limit became a 20% or 45% price cap (depending on the size of the venue), which

the law required to be printed legibly on each cket.

6

Over the years, the legislature periodically

imposed stricter penales on those selling ckets near venues and took steps to give the State

the power to police out-of-state actors dealing in ckets to events within New York.

Nonetheless, as NYAG’s report made clear in 1999, the law was both inconsistently enforced and

dicult to enforce. Underground brokers ourished, oen openly oung the law. By that year,

cket brokering had grown into a large underground economy typied by law-breaking, secret

cket holds, bribe paying, and a general state of corrupon at all levels.

2007 – Present: A Regulated Industry.

In 2007, in a sweeping legal change, the New York legislature decriminalized all resale of ckets

for prot, or “scalping,” and adopted an approach that sought to treat ckeng as a regulated

industry. With the price caps lied, brokers were now free to operate openly and sell ckets at

whatever prices consumers might pay. In the face of crics who warned that prices would rise

and brokers would reap unseemly prots, the sponsors of the Bill expressed some hope that the

new approach might, in fact, reduce cket prices on the resale markets. As Assemblyman Joseph

D. Morelle argued at the me, “By allowing greater compeon for the resale dollar, we may

actually see a decrease in secondary prices, which is … ulmately best for the consumer.”

7

3. The governing statutory provisions are found in New York Arts and Cultural Aairs Law, Article 25 (“N.Y. Arts & Cult. A. L.”).

4. Kerry Segrave, Ticket Scalping: An American History, 1850-2005 (2006), p. 55.

5. N.Y. General Business Law §§ 167-69k (McKinney 1922) (repealed 1983).

6. The following notice was required to be printed on tickets:

“If the venue to which this ticket grants admission seats 6000 or fewer persons, this ticket may not be resold for more than 20%

above the price printed on the face of this ticket, whereas if the venue to which this ticket grants admission seats more than 6000

person, this ticket may not be resold for more than 45% above the price printed on the face of this ticket.”

7. Oce of Joseph D. Morelle, “Morelle Bill Establishing Free Market for Ticket Resellers Passes Assembly” (May 29, 2007),

available at

http://assembly.state.ny.us/mem/Joseph-D-Morelle/story/22938.

8

The operang premise of the 2007 law was not to completely deregulate cket resale, but

to legalize it pursuant to regulaon and taxaon. Pre-2007, many of the brokers operated in

open violaon of the law; the 2007 law introduced a revised licensing system supervised by

the Secretary of State. The licensing system required, among other things, various disclosures

of ckets sold, the posng of a bond to cover counterfeit ckets, and the payment of a $5,000

annual fee.

Above all, the 2007 law represented

a new and experimental approach

to the cket industry, made clear by

the fact that the law regularly sunsets

and is therefore subject to ongoing

nkering by the legislature. The rst

adjustments came in 2010, when the

law underwent major changes, three

of which are important here. First,

for the rst me, the law banned

the use of cket-buying soware,

or “Bots.” The New York Senate

commentated that such soware is

“used by unscrupulous speculators to

purchase ckets at inial sale ahead

of consumers intending to aend an

event,” and put enforcement dues

in the hands of the Aorney General.

8

Evident in the ban on Bots and the

legislature’s commentary is the idea that cket buying, when presented to the public as a fair

contest, should in fact be fair, and not subject to manipulaon by soware or similar techniques.

In other words, the legislature prefers that the ability to obtain ckets be based on factors like

showing up at the right me or simple luck of the draw, as opposed to gaining an advantage

through soware that funcons dierently than a human could.

Second, an important 2010 legal reform addressed growing service fees imposed by primary

cket sellers and their cket vendor agents, such as Ticketmaster or Telecharge. It mandated, for

the rst me, that any fees charged for “special services” must be “reasonable.”

9

Third, the law

barred non-transferrable paperless ckets, as discussed in greater detail later in this Report.

10

The clear tenor of the ckeng statute is to make cket brokering into a regulated industry and

connue “safeguarding the public against fraud, extoron, and similar abuses.” Ticket brokers

are not illegal, but must obtain a license, post bonds, disclose their acvies to the Secretary of

State, and avoid using prohibited Bots. Whether the new system has operated in the interests

of New York cizens remains an open queson of public policy.

8. New York State Senate Introducer’s Mem., SB No. 3840-A.

9. N.Y. Arts & Cult. A. L. § 25.29 (as amended July 2, 2010).

10. Id. § 25.30.

What’s a Bot?

A Ticket Bot is soware that automates

cket-buying on plaorms such as

cketmaster.com.

Automaon lets the Bot (1) perform

each transacon at lightning speed, and

(2) perform hundreds or thousands of

transacons simultaneously.

As a result, in the rst moments aer

ckets to a top show go on sale, Bots

crowd out human purchasers and can

snap up most of the good seats.

9

CURRENT LAW

New York State law prohibits engaging “in the business of reselling any ckets to a place of

entertainment” within New York State without rst procuring “a license.

11

Those who resell, oer

to resell, or purchase with the intent to resell ve or more ckets without a license are guilty

of a misdemeanor and subject to penales.

12

Addionally, the law requires that brokers post

a $25,000 bond with their license applicaon to ensure compliance with the law’s provisions

and cover damages to their customers from any misconduct.

13

Brokers that resell ckets online

must also display a hyperlink to a copy of their licenses,

14

and they must display the face value of

ckets along with the resale prices.

15

New York State law also makes it illegal for brokers to use Bots to bypass security measures on

the websites of cket vendors, such as Ticketmaster, or to maintain any interest in or control of

such Bots.

16

Anyone who violates these provisions is subject to penales and the forfeiture of

prots.

17

No current federal law specically prohibits the use of Ticket Bots, but legislaon has been

proposed that would do so. The Beer On-line Ticket Sales Act of 2014 or the BOTS Act, supported

by Senator Charles Schumer, would prohibit, as an unfair and decepve act, the sale or use of

Ticket Bots. It would also provide for criminal penales for those who engage in this conduct.

11. Id. § 25.13.

12. Id. §§ 25.09(2), 25.35.

13. Id. § 25.15.

14. Id. § 25.19.

15. Id. § 25.23.

16. Id. § 25.24.

17. Id.

10

WHO’S WHO IN THE TICKET INDUSTRY

11

FINDINGS

A. The General Public Loses Out on Tickets to Insiders and

Brokers.

The majority of ckets for popular concerts are diverted away from the general public. First,

various “hold” and “pre-sale” programs reduce the total number of ckets available to the

general public. Then, of those ckets that remain, brokers use a number of methods including

Bots to seize a large poron of the remaining ckets. Brokers even sell ckets that they do not

actually own, known as “speculave” ckets, to fund their later purchases.

1. The Majority of Tickets for Popular Concerts Are Not Reserved

For the General Public.

It may come as no surprise to fans that many concert ckets are never made available to the

general public, but there is lile informaon available as to where precisely those ckets actually

go. To bring some light to this issue, NYAG has obtained and analyzed informaon regarding the

allocaon and distribuon of ckets from the largest promoters, Live Naon and AEG, for the

top-grossing shows in New York for the years 2012-2015.

NYAG found that, on average, only about 46% of ckets are reserved for the public. The remaining

54% of ckets are divided among two groups: holds (16%) and pre-sales (38%).

18

Holds are ckets

that are reserved for industry insiders, such as arsts, agents, venues, promoters, markeng

departments, record labels, and sponsors. Pre-sales make ckets available to non-public groups

before they go on sale to the general public. The two most common pre-sale events are for

credit card holders and members of fan clubs, but venues, promoters, or other groups may run

pre-sale events as well. Brokers, as discussed below, oen begin harvesng ckets at these pre-

sale events and later during the general on-sale.

18. The methodology for this analysis is in the Appendix.

12

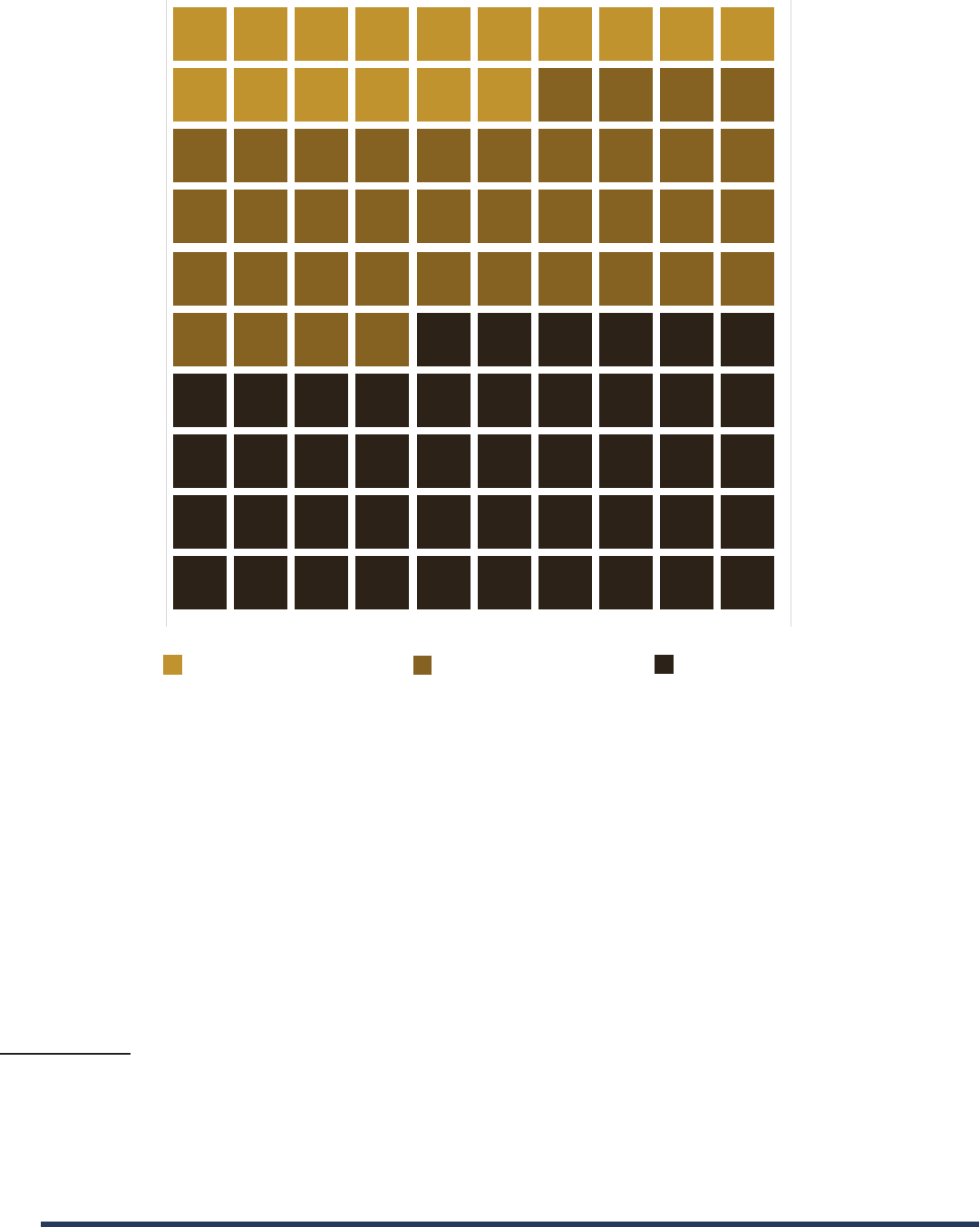

Figure 1. Less Than Half of Tickets Are Reserved for the General Public.

Source: Live Naon/Ticketmaster (2012 – 2013) and AEG (2012 – 2015)

19

Among the top grossing shows in New York, approximately 16% of all ckets were reserved

through “holds” for industry insiders: arsts, venues, agents, markeng departments, sponsors,

promoters, and execuves.

20

Oen, venues are the biggest beneciaries of these holds. For

example, Madison Square Garden was typically allocated more than 900 ckets per concert

and Barclays Center was allocated an average of 500 ckets per concert for the highest grossing

concerts held at those venues.

For some concerts, cket holds account for well over 16% of the available ckets. For instance, a

Kanye West show at Barclays Center held 29% of ckets for insiders, including over 2,000 ckets

for the promoter and more than 500 ckets for the venue. In all, fourteen of the State’s most

popular shows held at least 20% of available ckets for insiders, as shown in Figure 2. Holding

a large number of ckets is not necessarily a pracce among all shows – the Vans Warped Tour

2013 and Barry Manilow concerts, both at the Nassau Coliseum, held 5% or less of ckets.

19. The methodology for this analysis is in the Appendix.

20. It is worth noting that a hold simply represents a reservation, and that in most cases a group that has been allocated tickets

through a hold will not use a portion of those tickets. In these instances, the tickets are released back to the promoter, who will

typically make the tickets available for sale to the public. Because the tickets are usually not released through a publicized on-sale

event, tickets released in this manner are often purchased by brokers who are constantly searching for new tickets that are made

available closer to the date of the event.

Ticket Allocaon

Holds for Insiders

Pre-Sale Events

General Public

13

Figure 2. Fourteen Popular Shows Held at Least 20% of Tickets for Insiders.

Source: Live Naon/Ticketmaster (2012 – 2013) and AEG (2012 – 2015)

21

Filtered for shows with 20% or more total capacity placed on hold

Approximately 38% of ckets to the most popular shows in New York were reserved for “pre-

sales,” advance sales to select groups of fans and cardholders of major banks and nancial

instuons.

22

These nancial instuons, including American Express, Cibank, and Chase, have

negoated agreements whereby their cardholders have the opportunity to purchase ckets

21. The methodology for this analysis is in the Appendix.

22. For the top shows, it is often the case that all of the tickets that are made available through the pre-sale events are sold. For

less popular shows, tickets set aside for pre-sale events can go unsold. When tickets set aside for a pre-sale event are not sold, the

unsold tickets are reallocated to the initial public on-sale.

Trey Songz

Madison Square Garden

(Theater) on 3/1/2012

20%

Jusn Bieber

Madison Square Garden on

11/29/2012

28%

Jusn Bieber

Madison Square Garden on

11/28/2012

28%

Keith Urban

Madison Square Garden on

1/29/2014

20%

The Voice

Beacon Th eatre on 7/9/2014

22%

Ricardo Arjona

Madison Square Garden on

2/26/2012

23%

Fresh Beat Band

Madison Square Garden

(Theater) on 11/30/2013

24%

Fresh Beat Band

Madison Square Garden

(Theater) on 11/29/2013

24%

Kanye West

Barclays Center on

11/20/2013

21%

Kanye West

Barclays Center on 11/19/2013

29%

Drake

Jones Beach on 6/16/2012

20%

Luke Bryan

Nassau Coliseum on

2/7/2013

20%

Farm Aid

Saratoga Perf orming Arts

Center (SPAC) on 9/21/2013

22%

Fleetwood Mac

Madison Square Garden on

4/8/2013

24%

NKOTB

Nassau Coliseum on 6/1/2013

24%

Promoter

LiveNao n

AEG

14

before the ckets are released for sale to the general public. Importantly, fans are not necessarily

the ones purchasing ckets released in pre-sale events. For popular events, brokers, realizing the

advantages of pre-sale programs, purchase heavily and oen use illegal Bots to maximize their

yield in pre-sales, as discussed in greater detail below.

23

While the majority of pre-sale events

are conducted by credit card companies, members of other groups, including fan clubs, social

media websites, and specialty shopping sites also receive advance opportunies to purchase

ckets.

The number of ckets reserved for pre-sale events can be quite large for some concerts. For

example, for more than 30 of New York’s most popular concerts, at least half of the ckets were

set aside for pre-sale events. Figure 3 idenes ten shows that made more than half of the

ckets available through pre-sale events where none of the ckets were explicitly reserved for

fan clubs.

Figure 3. Ten Popular Shows Reserved Over 50% of Tickets

Through Pre-Sales Events, None Explicitly Earmarked for Fan Clubs.

Source: Live Naon/Ticketmaster (2012 – 2013)

24

Filtered for shows with more than 50% of total capacity sold through

pre-sale events and no ckets specically earmarked for fan clubs

23. Even setting aside the problem of brokers, cardholder pre-sales may disadvantage many fans. They reserve tickets for hold-

ers of select credit cards, who may generally be wealthier than fans who lack those cards and the benets that come with being

a cardholder. As a result, these pre-sales give wealthier fans a better chance of getting tickets at face value, while decreasing the

supply of face-value tickets available to less wealthy fans.

24. The methodology for this analysis is in the Appendix.

Fleetwood Mac

Madison Square Garden on 4/8/2013

61%

Coldplay & Jay-Z

Barclays Center on 12/31/2012

70%

Coldplay &

Jay-Z

Barclays Center on 12/30/2012

52%

Jay-Z & Jusn

Timberlake

Yankee Stadium on 7/20/2013

69%

Jay-Z & Jusn

Timberlake

Yankee Stadium on 7/19/2013

71%

SteelyDan

Beacon Theatre on 10/8/2013

64%

SteelyDan

Beacon Theatre on 10/5/2013

65%

SteelyDan

Beacon Theatre on 10/4/2013

64%

SteelyDan

Beacon Theatre on 10/1/2013

64%

SteelyDan

Beacon Theatre on 9/30/2013

64%

Promoter

LiveNao n

15

Holds and pre-sales can leave few ckets for the public. Indeed, for many of the top shows, less

than 25% of ckets were actually released to the general public in an inial public on-sale. For

example, just over 1,600 ckets (12% of all ckets) were released to the public during the inial

public on-sale for a July 24, 2014 Katy Perry concert at Barclays Center. Similarly, for two Jusn

Bieber concerts at Madison Square Garden, on November 28, 2012 and November 29, 2012,

fewer than 2,000 ckets (15% of all ckets) to each show were released to the public during the

inial public on-sale.

2. Brokers & Bots Buy Tickets in Bulk, Further Crowding Out Fans.

The broker industry, while not the explicitly underground industry it was in the 20th century,

remains dicult to learn about and oen operates in violaon of one or more State laws.

The average fan vying to purchase a cket to a popular concert has lile hope of compeng

against brokers, many of whom use illegal and unfair means to purchase ckets. Brokers are

able to purchase large quanes of ckets to popular events by (a) employing illegal Bots, and/

or (b) exploing their industry knowledge and relaonships to get access to ckets.

a. Ticket Bots Amass

Hundreds or Thousands

of Tickets in an Instant.

A Ticket Bot is a soware

program that automates

the process of searching

for and buying ckets to

events on cket vendor

plaorms, such as

Ticketmaster. Using Bots,

a broker can automate the

process of searching for

and buying ckets so that it occurs in the blink of an eye, and conduct tens, hundreds, or even

thousands of lightning-fast transacons at the same me.

To successfully buy thousands of ckets, Bots must perform four dierent funcons. These

funcons may be handled by one Bot or several.

First, spinner, or “drop checker,” Bots constantly monitor ckeng sites to detect the release, or

“drop,” of ckets. Ticketmaster has stated that spinners can account for as much as 90% of the

trac to its website.

25

Second, Bots automate the search for and reservaon of ckets that are up for sale. Here,

brokers exploit the fact that most ckeng plaorms “reserve” ckets for a few minutes to give

the (human) customer me to complete the purchase. Brokers take advantage of this feature

by conducng mulple near-instantaneous searches at the precise moment ckets are released

for sale, throwing hundreds of ckets into reserve and removing them from the pool of ckets

25. Ticketmaster L.L.C. v. RMG Technologies, Inc., 07-Civ.-2534 (C.D. Cal.) (Application for Entry of Default Judgment); Ben Sisario &

Emily B. Hager et al., “Fair Ticketing: Fans Before Scalpers,” N.Y. Times Video (May 27, 2013),

available at

http://nyti.ms/13V6sdO.

“...According to Ticketmaster, bots have been used to

buy more than 60 percent of the most desirable tickets

for some shows….”

Concert Industry Struggles With ‘Bots’ That

Siphon Off Tickets

16

available for purchase. The broker may then review the search results and choose which seats

to buy.

26

Figure 4 shows an example of a Bot that has searched for and reserved several groups

of ckets, displaying the groups and the me remaining for the Bot-user to purchase each one.

Figure 4. Bot Displays Time Remaining to Buy

Temporarily “Reserved” Tickets.

Source: Ticketbots.net

Third, Bots automate the process of purchasing ckets, using dozens or hundreds of purchaser

names, addresses, and credit card numbers. The names of the “buyers” may be simply invented,

or they may be borrowed from real people.

Fourth, and nally, Bots must defeat the an-Bot security measures that most cket-selling

plaorms employ. The most obvious of the cket vendors’ defensive tools that Bots must bypass

is the “CAPTCHA” test (“Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans

Apart”). This test usually requires that a user prove she is human by reviewing text that is

distorted or obscured and entering those characters into a text box.

26. Some brokers use this interval to oer the temporarily reserved tickets for sale on secondary market platforms such as Stub-

Hub at a given markup, and only if the resale is quickly consummated do they then actually buy the reserved tickets from the

primary ticket vendor. This ability to use temporary reserve to avoid risk greatly undermines a shibboleth repeated to NYAG

during our investigation, that brokers benet the ticket industry as a whole, including artists, promoters, and venues, by taking on

nancial risk through up-front purchases of lots of tickets which they may be unable to resell.

17

Figure 5. Ticket Vendors Use Dierent Types of CAPTCHA.

Unfortunately, many Bot programmers have been able to bypass these forms of CAPTCHA.

Over the years, Ticketmaster has repeatedly refurbished its CAPTCHA program, using dierent

versions of CAPTCHA created by third pares such as Google and Solve Media.

27

While these

CAPTCHAs may have stopped some Bots, more sophiscated Bot programmers quickly adapted.

In many cases, they collected thousands of the new CAPTCHAs and used them to “train” their

soware to “read” the new CAPTCHAs through improved opcal character recognion. In other

instances, the Bots transmit in real-me images of the CAPTCHAs they encounter on Ticketmaster

and other sites to armies of “typers,” human workers in foreign countries where labor is less

expensive. These typers – employed by companies such as Death by CAPTCHA, Image Typerz,

and DeCaptcher – read the CAPTCHAs in real-me and type the security phrases into a text box

for the Bot to use to bypass cket vendors’ defenses and use their sites.

28

Addionally, at various points, Ticketmaster abandoned CAPTCHAs for its mobile app on the

iPhone plaorm, based on the premise that it could beer verify idenes on mobile and

therefore did not need a CAPTCHA test. Our invesgaon of brokers reveals that some have

targeted the CAPTCHA-free mobile plaorm by either designing Bots to mimic mobile devices

or by using an arsenal of actual mobile devices to buy ckets.

27. Some CAPTCHAs incorporate technology that attempts to identify Bots before an image is even shown, to present an easier

test to likely humans and more dicult CAPTCHAs to suspected Bots. See, e.g., Solve Media – High Security Standards, http://

solvemedia.com/security/index.html. Many sophisticated Bot developers have bypassed these additional measures.

28. Some CAPTCHAs now do away with security phrases and use other types of puzzles. See, e.g., Google – “Introducing No CAPT-

CHA reCAPTCHA,” https://googleonlinesecurity.blogspot.com/2014/12/are-you-robot-introducing-no-captcha.html. It remains to

be seen if these new approaches will be harder to bypass, especially for Bots that use teams of human typers.

18

To eecvely beat out the many fans (and other Bots) aempng to search for and reserve ckets

at the start of a sale, most Bots simultaneously aempt mulple connecons to the cket vendors’

systems, oen dozens or even hundreds at a me. These connecons are oen responsible for

sudden massive increases in Internet requests to ckeng websites when ckets are released.

To conceal that these large numbers of concurrent connecons originate from a single source,

most Bot users purchase hundreds or thousands of proxy IP addresses to use for each separate

connecon aempt. Moreover, because cket vendors block or slow trac connecons from IP

addresses that appear to be used by Bots, many Bots automacally rotate through their stores of

proxy IP addresses to bypass detecon and blocking. Bot users also typically register hundreds

or thousands of e-mail addresses, again to conceal that a single purchaser is responsible for

many concurrent transacons and to circumvent security measures designed to prevent Bots

from purchasing ckets.

With these capabilies, Bots can be extremely eecve for brokers. First, they can buy hundreds

of ckets in moments. NYAG has idened many instances in which Bots were able to purchase

hundreds of ckets within moments of the release of ckets to the general public or through a

pre-sale, including the examples shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Bots Buy Huge Numbers of Tickets Moments Aer Release.

Source: NYAG Invesgave Materials

1,012

tickets in

1 minute

U2 2015 Tour

Madison Square Garden

Bought by one bot on December 8, 2014, for a

July 19, 2015 concert.

520

tickets in

3 minutes

Beyoncé

Barclays Center

Bought by one Bot on March 4, 2013 for an

August 5, 2013 concert.

15,087 tickets in 1 day

U2 2015 Tour

Twenty Different Venues

Bought by two Bots on December 8, 2014 for

twenty concerts in the same tour across North

America.

522

tickets in

5 minutes

One Direction

Jones Beach

Bought by one Bot on April 14, 2012 for a June

28, 2013 concert.

19

Addionally, by being rst in line, Bots can also purchase the most desirable seats to many shows.

For example, NYAG reviewed a case study by one cket vendor showing that Bots purchased

more than 90% of the most desirable ckets to one show. As part of its own analysis, NYAG

found that, of the 251 ckets one Bot operaon purchased to a May 5, 2014 Coldplay concert

at the Beacon Theatre, 148 of those ckets were in the rst seven rows of the theater. This

amounted to more than 60% of seats in those seven rows.

As a result of these huge advantages, Bots are able to purchase many ckets to New York events.

The sources we interviewed uniformly stated that the usage of Bots has reached epidemic

proporons in the ckeng industry. Indeed, NYAG found that three brokers using Ticket Bots

collecvely purchased more than 140,000 ckets to events in New York over a three-year period

between 2012 and 2014.

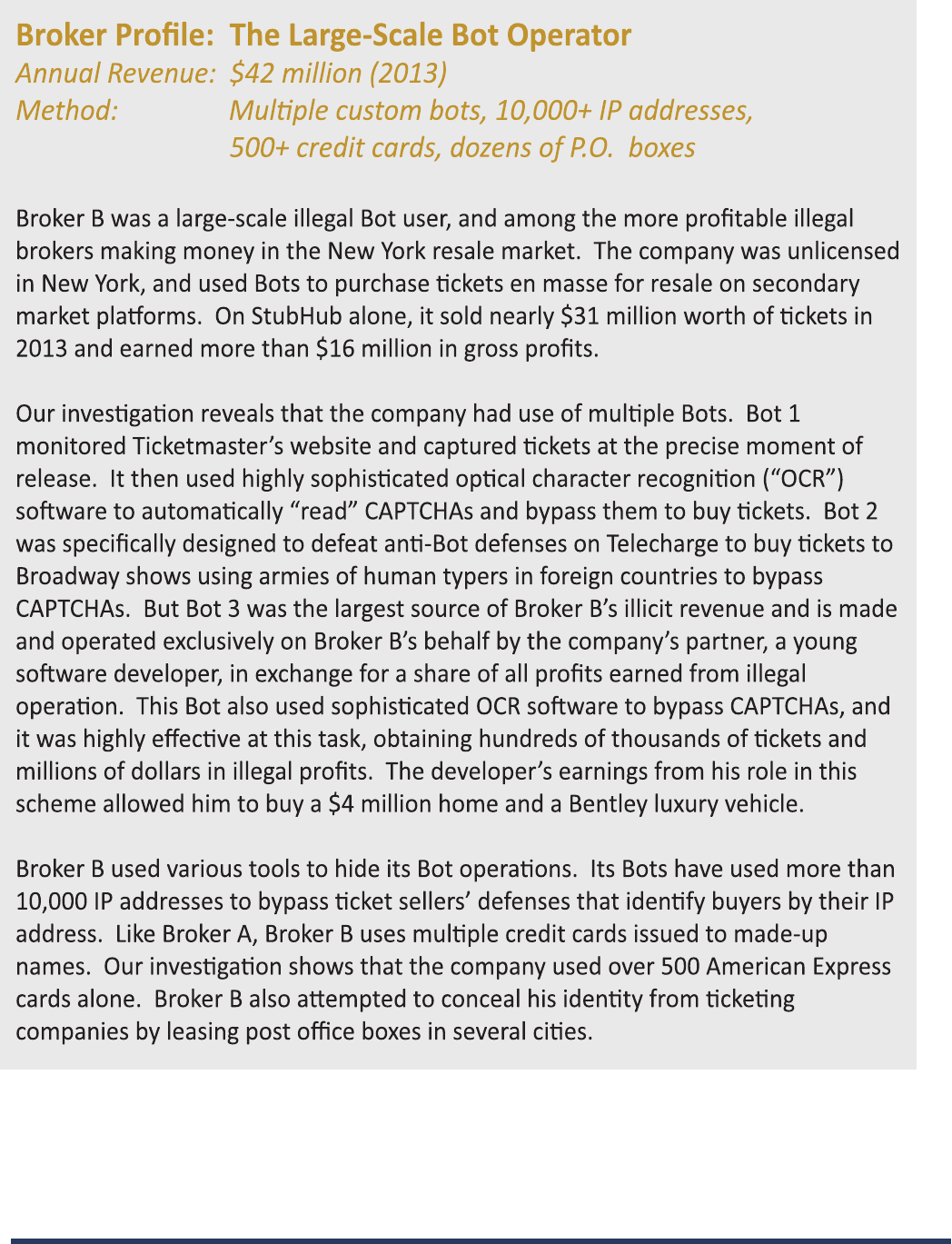

Broker Profile: The One-Man Bot Broker

Revenue: $1.4 million from events in New York (2014)

Method: Bot mimicking Ticketmaster app & 1,000+ credit cards

Broker A was an illegal Bot user who represents a typical species of broker. The

company is a one-man operaon that opened when its proprietor was sll in

college. The company paid overseas programmers for sophiscated cket-buying

Bots designed to mimic the Ticketmaster iPhone app and defeat its an-Bot

defenses. To maximize its yield, and avoid cket limits, the company obtained more

than 1,000 credit cards, many of which used ficous names, each designed to

appear to Ticketmaster as a different individual.

Armed with its Bot and collecon of credit cards, the company directed legions of

purchase requests at popular shows; its acons are part of what led to the quick

sellouts. Its harvest was put up for resale on numerous plaorms, including Stub-

Hub and Vivid Seats, and its own site. While it made much of its money from New

York venues, the company is not licensed in New York.

20

21

b. Even without Bots, Brokers Use Industry Knowledge and

Relaonships to Gain an Edge Over Fans.

Brokers who do not use Bots nevertheless have several signicant advantages over the average

fan based on their knowledge of the industry and relaonships.

First, brokers in many instances take advantage of pre-sale events oered to holders of certain

credit cards. Brokers are aware of which credit cards can be used in pre-sales and open accounts

for these credit cards. Brokers also closely follow cket release schedules and are prepared to

purchase ckets at pre-sales, when the compeon for ckets is oen less than during a public

on-sale.

In many instances, arsts try to get ckets into the hands of fans by oering pre-sales to ocial

fan clubs, for example by issuing special codes to fan clubs that allow members to log into the

pre-sale on cket vendor sites ahead of the general on-sale. Unfortunately, brokers oen sign

up for these fan clubs, obtain the codes, and either use them themselves or sell them to other

brokers.

Second, Brokers have resources to aempt many concurrent connecons. Brokers understand

that it is important to try to reserve and purchase as many ckets as possible during the rst

moments of an on-sale. Many brokers therefore use mulple computers or mobile devices to

try to connect to ckeng websites at the same me. NYAG spoke with one broker who owned

100 mobile devices and claimed to use dozens of those at a me by himself to try to purchase

ckets. Some brokers employ dozens of people simply to have many humans trying to reserve

and purchase ckets at the same me.

Third, many Brokers maintain direct relaonships with venues and sports teams. In these cases,

brokers are able to purchase ckets without compeng for ckets through the ckeng website.

Barclays Center, for example, has provided several brokers who own season ckets to Brooklyn

Nets games with the opon to purchase several hundred ckets to most other events at the

venue, including all music concerts. More than 500 ckets to an Elton John concert at Barclays

Center were distributed to brokers in this manner.

22

c. Ticket Limits Are Not Regularly Enforced.

The consumer may be familiar with the cket limits that are encountered on the websites of

most cket vendors. Popular arsts and their promoters typically seek to have vendors, like

Ticketmaster or AXS, impose a limit on the number of ckets that any individual can purchase

for any event. For concerts, a typical limit is eight ckets per purchase; more popular concerts

set smaller limits. The theory behind limits is intuive and obvious: by liming the number of

ckets any one individual can purchase, ckets will be more fairly distributed. If cket limits

were truly eecve – if it were impossible for any one person to buy more than the stated

number of ckets – broker acvity would be greatly limited.

Our invesgaon suggests that in the case of some cket vendors, including Ticketmaster, cket

limits do not always have the eect the public would expect. Ticketmaster implements cket

limits by restricng the number of ckets that can be purchased in a single transacon (a per-

transacon limit). It does not, however, restrict at the me of sale the number of ckets that can

be purchased by a user through mulple transacons (a per-person limit). In other words, when

an arst requests an eight-cket limit, Ticketmaster will permit a user to purchase only eight

ckets in a single transacon, but then will allow the same user to make addional purchases of

eight ckets each.

Broker Profile: Licensed Broker

Revenue: $25.4 million (2013)

Method: Employees buy ckets en masse

Broker C is a licensed �cket broker. In opera�on since the 1990s, the company has

become highly profitable under the new �ckets law. The company employs approxi-

mately 25 full-�me employees; each employee is paid a wage to keep his or her

own accounts and purchase, using his or her own American Express credit cards, as

many �ckets as possible for shows or events decided upon by management. The

company pays its annual licensing fees to the New York Secretary of State.

Broker C is an example of the 2007 law in opera�on. On the one hand, the

company pays its licensing fees, discloses its ac�vi�es, and is in apparent compli-

ance with most of the regula�ons. On the other hand, the company’s sizable annual

profits – $4.8 million in gross profit in 2013 – are direct evidence of the prices that

the public pays on the secondary �cket markets.

23

Ticketmaster can aempt to idenfy violaons of the cket limit aer ckets have been sold

by canceling those transacons that exceeded the limit the arst had requested. It will only

undertake this review, however, if an arst specically requests the audit. Yet many arsts seem

unaware of this fact. For example, a sophiscated representave of several top arsts playing the

largest arenas told NYAG they had been unaware that Ticketmaster required a separate auding

request to enforce limits the arst had already requested, and had therefore never made such

a request. Thus, although some arsts are trying to make ckets available to average fans by

pricing them below market value and seng cket limits, the lack of real-me enforcement per

user at the point of purchase (or thereaer) undermines their eorts.

The main beneciary of the unenforced cket limits is, of course, the broker industry. As repeat

players, the brokers know well that the limits are rarely enforced. Our interviews with brokers

and others in the industry, and our review of cket purchasing data, reveal that the limits,

enforced or not, are easy to evade. The eect of these shortcomings in enforcement of cket

limits is exacerbated where brokers use Bots to speed up their purchases above the limits, to

the detriment of ordinary members of the public. As a result, brokers have an advantage as

compared to ordinary buyers, who believe the phrase “cket limits” means what it says.

d. Brokers, With and Without Bots, Buy Up Many Tickets to New York Events.

Evidence that brokers are responsible for the purchase of large quanes of ckets can somemes

be seen in sales data that tracks the purchasing acvies of enes holding mulple credit cards.

For example, Figure 6 below shows American Express cardholders who purchased more than

$3 million in ckets through Ticketmaster for events in New York State and surrounding areas

using their American Express cards. A single broker used 149 dierent American Express cards

to make more than 38,000 purchases totaling over $12 million just from 2013-2015, while other

brokers racked up similarly shocking volumes of purchases, somemes using just a handful of

credit cards.

24

Figure 7. Twelve Brokers Each Purchased More than $3 Million in Tickets.

Source: American Express Purchases to Ticketmaster for Events

in New York & Surrounding Areas (2013-2015)

29

29. The methodology for this analysis is in the Appendix.

$12,251,282

throug h

38,366

transactions an d

149

cards .

$11,668,951

throug h

45,711

transactions an d

87

cards

.

$6,175,235

throug h

16,805

transactions an d

644

cards

.

$3,838,637

throug h

13,678

transactions an d

170

cards

.

$3,129,622

throug h

12,450

transactions an d

132

cards

.

$5,595,105

throug h

26,656

transactions an d

25

cards

.

$4,625,014

throug h

11,680

transactions an d

54

cards

.

$3,697,400

throug h

11,046

transactions an d

20

cards .

$3,592,798

throug h

10,039

transactions an d

23

cards .

$3,309,475

throug h

7,992

transactions an d

289

cards

.

$3,361,108

throug h

18,776

transactions an d

4

cards

.

$3,280,623

throug h

8,061

transactions an d

57

cards

.

25

e. Brokers Sell Tickets at Substanal Markups.

Brokers prot by selling ckets at a substanal markup over face value. NYAG studied six cket

brokers and found they marked up their ckets an esmated 49% on average, ranging by broker

from an average of 15% to 118%. Figure 8 depicts the markups charged by representave brokers

for their most protable shows.

Figure 8. Examples of Six Brokers’ Markups Show Large Prots.

Source: Transaconal sales data for select brokers (2011-2014)

30

30. The methodology for this analysis is in the Appendix.

$1,600

$815

$1,600

$350

$218

$218

$544

$443

$544

$250

$570

$693

$64

$101

$1,602

$79

$4,400

$3,650

$3,526

$1,249

$932

$925

$1,590

$1,155

$1,008

$1,306

$1,221

$999

$1,404

$1,351

$1,256

$7,244

$5,336

$4,635

$0 $1,000 $2,000 $3,000 $4,000 $5,000 $6,000 $7,000 $8,000

Barbra Streisand @ Barclays Center

NY Rangers v. LA Kings @ Madison Square Garden

Barbra Streisand @ Barclays Center

U2 @ Madison Square Garden

Stanley Cup Finals @ Madison Square Garden

Stanley Cup Finals @ Madison Square Garden

Eric Clapton @ Madison Square Garden

NHL Conf. Finals @ Madison Square Garden

Eric Clapton @ Madison Square Garden

Yusuf Islam/Cat Stevens @ Beacon Theatre

NHL Conf. Finals @ Madison Square Garden

NHL Conf. Finals @ Madison Square Garden

Ed Sheeran @ Madison Square Garden

Eagles @ Madison Square Garden

Pearl Jam @ Barclays Center

One Direction @ Madison Square Garden

Barbra Streisand @ Barclays Center

One Direction @ Beacon Theatre

Ticket Face Value Markup Amount

Custom Bot

Broker A

Custom Bot

Broker B

Bot Broker B

Non-Bot

Broker B

Non-Bot

Broker A

Bot Broker A

$94

$228

26

Figure 9. Brokers Charge Large Markups.

31

Source: Source: Transaconal sales data for select brokers (2011-2014)

Our analysis also reveals that the brokers that commanded the greatest markups in the cket resale

market were those that used Ticket Bots, and, moreover, that the most sophiscated, custom

Ticket Bots were associated with the highest markups. This may be because the sophiscated,

custom Bots were able to purchase the most desirable seats, which could be resold for the

highest prices.

f. Speculave Tickets Increase Confusion and Risk for Fans.

In early December 2015, ckets purporng to be for Bruce Springsteen’s 2016 “River Tour”

began appearing on secondary sites like StubHub, TicketNetwork and Vivid Seats. Some ckets

were even adversed for inated prices of as much as $5,800 per cket. The catch? No such

ckets had yet been released. What brokers were selling were “speculave ckets,” that is to

say, ckets that they planned, or hoped, to buy later.

When a speculave cket is sold, the broker then tries to purchase an actual cket, at a lower

price, to provide to the buyer. The broker pockets the dierence between the price at which he

pre-sold the cket and the price at which he later bought the cket. Speculave ckets harm

both consumers and the cket industry. In many cases, consumers are just defrauded – they

do not receive the specic seats they paid for, instead receiving ckets for some other seats.

In some cases, consumers receive no ckets at all. Speculave cket sales also drive up prices

for consumers and oen cause widespread confusion and frustraon among consumers, who

wonder how ckets can appear on the resale market before ckets are even released to the

public.

In 2014, singer Eric Church expressed his frustraon with such ckeng: “They’re taking the

money, and they’re not even on sale. There’s no ckets on sale yet. They don’t really have them

– they’re promising the fact that they can get them. It’s a damn scam is all it is. It’s the maa.” In

the case of the 2016 Springsteen tour menoned above, NYAG asked StubHub, TicketNetwork,

and Vivid Seats to take down the speculave cket lisngs, and they all complied. This one-me

enforcement acon was eecve in that instance, but the problem is recurrent.

31. The methodology of this study appears in the Appendix.

Broker

Avg.

Cost

Avg.

Resale

Price

Markup

Highest

Markup

Amount Percent

Custom Bot A $145 $317 $172 118% 7,154%

Custom Bot B $104 $188 $84 81% 2,190%

Bot A $100 $137 $37 36% 637%

Bot B $105 $137 $32 30% 456%

Non-Bot Broker A $78 $101 $23 29% 1,537%

Non-Bot Broker B $111 $128 $17 15% 1,601%

27

g. The Market Structure Is Atypical.

Another nal point to keep in mind concerning this industry: the typical market structure is

skewed. For one, ckets are oen sold on the primary market for a face value that is below

market price. Although this may sound surprising, our invesgaon suggests it is common

and reects various factors. For one thing, maers of goodwill and reputaon in the sale of

ckets are important to certain performers. That is clearest, for example, for events where

the promoter has non-commercial goals – like Pope Francis, who distributed free ckets for his

public appearances – or at events like the New York City Center’s annual Fall for Dance Fesval,

which includes world-renowned performers but sells ckets for just $15, “in keeping with the

Fesval’s commitment to make dance accessible to everyone.”

32

Even more explicitly commercial acts somemes price their ckets below what they might charge

to make them accessible to younger fans or those of ordinary incomes. The band Fugazi, acve

over the 1990s and early 2000s, for example, long kept its cket prices at $5.

33

Pearl Jam, among

the most popular bands of the 1990s, set its cket prices at or below $20 to make it possible

for young fans to aend its concerts. As the band said in prepared tesmony before Congress,

“Although, given our popularity, we could undoubtedly connue to sell out our concerts with

cket prices at a premium level, we have made a conscious decision that we do not want to put

the price of our concerts out of the reach of many of our fans.”

34

Somemes a mixture of economic and non-economic moves is evident. A sports team, like the

Brooklyn Nets or New York Mets, might not want to be accused of “gouging” fans, and hoping

to build a loyal fan base, and so might price its ckets accordingly. Some sense of this came in

2009 when the New York Yankees experimented with much higher cket prices and were subject

to widespread cricism and unaering media coverage. The New York Post described the

Yankees’ new plan as “greed-driven-and-delivered” and the prices as “insanely and obscenely

high.”

35

Eventually, in the face of both cricism and poor sales, the Yankees lowered their prices

dramacally. Somemes even a prot-maximizing performer might set prices lower than market

value to guarantee a sellout and a full house for markeng purposes. Some of the promoters we

spoke with argued that a public sense of high demand and cket scarcity is necessary to create

strong demand for ckets. Hence, seng cket prices at a low level, so as to drive sales, may be

necessary to create the sense of a “sellout tour” that stokes demand to aend it.

Cheaper ckets could be very benecial to consumers, as long as they reap the benets. The

problem with this industry is that a middleman essenally takes the benets intended for the

consumer. In other words, the cket broker or reseller, able to buy up ckets before the public

gets a chance, prots from the lower priced cket – charging the consumer a much higher price

and pockeng the dierence. To further complicate the industry, the enes most able to stop

this pracce are either powerless or not economically incenvized to stop the pracce. Arsts

may want to avoid this from happening but have to rely on the venues to sell ckets. Venues

have an interest in selling out ckets and have lile incenve to put protecons in place. Ticket

32. Press Release, “New York City Center Announces 2015 Fall for Dance Festival” (July 29, 2015),

available at

https://www.nyci-

tycenter.org/content/misc/PressRelease-FFD15a.pdf.

33. John Pareles, “Review/Rock; Melodies Amid Rant, Thoughts Amid Rage,” N.Y. Times (Mar. 7, 1991),

available at

http://www.

nytimes.com/1991/03/07/arts/review-rock-melodies-amid-rant-thoughts-amid-rage.html.

34. Hearing of U.S. House Comm. on Gov’t Ops., Subcomm. on Info., Justice, Transp., & Ag., 103d Cong. (June 30, 1994).

35. Phil Mushnick, “Pricing fans out of Stadium no good for Yankees or MLB,” N.Y. Post (Apr. 27, 2014),

available at

http://nypost.

com/2014/04/27/pricing-fans-out-of-stadium-no-good-for-yankees-or-mlb.

28

vendors also have an interest in selling as many ckets as they can; they collect a fee with each

cket that is sold, a fee that is the same regardless of whether it is paid by you or a reseller.

B. High Fees for Unclear Purposes Raise Concerns

Next to sellouts, few issues seem to aggravate consumers as much as the addion of unexplained

“convenience” charges or “service” fees to the prices of ckets. These fees can be of considerable

cost to consumers as a percentage of a cket’s face value, or in absolute dollar terms. For

example, a cket to the Professional Bull Riding event at Madison Square Garden had $42 in fees

aached; a cket to

see Janet Jackson at

Jones Beach Theater

came with a $28 fee.

In 2010, the New

York legislature

amended the State’s

law governing cket

fees.

36

The statute,

as it stands, bans the

addion of

any

fee to a cket by a venue operator or its cket vendor except fees that are

associated with “special services” for which a “reasonable service charge” may be levied. The

statute states that special services include but are not limited to such services as “sales away from

the box oce, credit card sales

[37]

or delivery.” Thus, charges added to a cket’s face value violate

State law if they are either (1) mandatory, general fees, unconnected to the provision of “special

services,” or alternavely, when (2) such fees reach levels that are no longer “reasonable.”

A ban on the charging of mandatory fees unconnected to a bona de service is a common consumer

protecon measure. New York City, for example, expressly bars restaurants from adding general

surcharges to the prices on menus.

38

Relatedly, the U.S. Department of Transportaon considers

it an “unfair and decepve pracce” to adverse cket prices that do not include mandatory fees

and taxes.

39

The New York law on cket charges creates a similar rule by banning the charging

of fees unrelated to the provision of specialized services, and also regulang the fees that are

charged.

36. N.Y. Arts & Cult. A. L. § 25.29.1. The Senate Sponsor Memorandum summarized the provision as follows: “requires that service

charges in association with tickets sold be reasonable.”

37. Despite this provision, imposing a surcharge on credit card use is illegal under General Business Law § 518. (“No seller in any

sales transaction may impose a surcharge on a holder who elects to use a credit card in lieu of payment by cash, check, or similar

means”). See Expressions Hair Design v. Schneiderman, No. 13-4533 (2d Cir. 2015),

available at

http://law.justia.com/cases/fed-

eral/appellate-courts/ca2/13-4533/13-4533-2015-09-29.html.

38. New York City Rule § 5-59 provides: “A seller serving food or beverages for consumption on the premises may not add sur-

charges to listed prices. For example, a restaurant may not state at the bottom of its menu that a 10 percent charge or a $1.00

charge will be added to all menu prices.”

39. 14 CFR 399.84.

“I purchased a 30 dollar cket to see A View From

A Bridge. During the transacon I saw that a ten

dollar fee would be added for handling. Handling

what? I am using my own printer to print my own

cket!”

- Typical consumer complaint to NYAG about fees

1. Fees are Charged by Ticket Vendors and Venues.

Relying on publicly available informaon, NYAG conducted a broad study of the fees being

charged in New York State by 150 dierent venues and their cket vendors.

40

The examinaon

reveals substanal variaon in what fees are charged, but it also reveals some clear paerns.

First, it is worth nong that some outlets sell their ckets themselves; these venues are oen

smaller and non-prot. Examples include the Lancaster Opera House and the New York City

Ballet. These outlets or organizaons either do not charge any mandatory fees at all, or charge

a small service and/or handling fee for buying away from the cket oce that does not generally

vary with the price of the cket.

Most venues, however, sell their ckets pursuant to an exclusive contract with a cket vendor

like Ticketmaster or Tickets.com. This group includes the larger venues, such as Brooklyn’s

Barclays Center, Albany’s Times Union Center, and Bualo’s First Niagara Center. However,

smaller venues, like the Ulster Performing Arts Center in Kingston and the Stanley Center for the

Arts in Uca, also use cket vendors. Generally speaking, the venue/cket vendor combinaons

charge fees and use a variety of formulas to set them, such as adding a xed charge based on

the type of cket or charging some percentage of the total price of the ckets.

While it is ckeng vendors (mainly Ticketmaster) that bear the brunt of the complaints about

fees, some venues play a central role in seng such fees and share in the money that the cket

vendors collect. Our review of long-term contracts between Ticketmaster and large venues like

Barclays Center or Madison Square Garden reveals that the pares negoate the fee amounts —

including “convenience charges” or “service fees” (per cket) and “processing fees” (per order)

– that can be shared between the venue and cket vendor.

41

The venue may also ban the cket

vendor from levying other charges, such as “delivery fees” for PDFs of ckets.

Our examinaon of the fees charged in New York also allowed us to esmate the average fee

amounts charged by the larger venues in combinaon with three cket vendors for events

in this State: Ticketmaster, TicketWeb, and Tickets.com. On average, combining the fees

charged by these three vendors and their venue clients for 150 New York venues, we found an

average surcharge of 21% of the face value of a cket, which amounts to almost $8 in fees on

average. However, our invesgaon also revealed that in certain cases, cket fees charged were

surprisingly high in real dollar terms, even if they were not a large percentage of the face value

of the cket. The following chart shows examples of ckets for several events in which the fees

exceeded $25 per cket.

40. The methodology of this study appears in the Appendix.

41. Ticket vendors often enter into multi-year contracts with venue operators to sell tickets to all events at the operator’s facility.

The terms of these contracts generally set forth the convenience charges and other fees that Ticketmaster must collect, and the

portions of those fees and charges that it must deliver to the venue, as well as the portions that Ticketmaster can keep.

29

30

Figure 10. Examples of Large Fees for Select Events and Venues.

Source: Fees collected from Ticketmaster, Tickets.com & TicketWeb (2015)

Professional Bull

Riding: Built Ford

Tough Series

Radio City

Christmas

Spectacular

Brooklyn Nets vs.

Phoenix Suns

Janet Jackson:

Unbreakable

World Tour

Black Sabbath:

The End

$42

in fees or 21%

of face value

$41

in fees or 11%

of face value

$30

in fees or 7%

of face value

$28

in fees or 16%

of face value

$28

in fees or

16%

of face value

31

2. Event Ticket Fees are Higher than Most Online Vendors.

Because Ticketmaster, TicketWeb, and Tickets.com all conduct a major poron of their business

online, where costs are oen lower than for brick-and-mortar retailers, we examined other online

plaorms that, similar to cket vendors, interact with consumers on one side and sellers on the

other side, to assess whether charging consumers large services fees separate and apart from

the cket’s face value is nonetheless typical or perhaps necessary for ckeng. In this regard we

examined online vendors of ckets for airplane seats, such as Expedia and Priceline, and vendors

of ckets to lms, like Fandango and MovieTickets.com. We also examined online plaorms

that sell a broader mixture of goods, like Amazon and Etsy, to see if they charge consumer fees

separate and apart from the posted prices.

Our examinaon suggests that, among online plaorms, the vendors of event ckets appear to

charge fees to consumers that are higher than most other online vendors – in fact, most of the

online plaorms we examined charge no “general” fees to consumers for the sale of ckets or

goods and post prices that already reect the full cost to the consumer. That is true of Amazon

and Etsy, and it is also typically true even of vendors of airline ckets, like Expedia and Priceline.

42

The main excepons are the sites that sell movie ckets, because those vendors charge consumer

fees that are close in magnitude to the average fees charged in live event ckeng. Fandango,

for example, charges moviegoers a “transacon fee” between 75 cents and $2.50 per cket, and

a “convenience fee” of $1.50 per cket.

It is unclear what services are covered by the “convenience charges,” “service fees,” and

“processing fees” collected by online vendors of live event ckets, and why those services warrant

charging consumers fees that are higher than in most other online contexts. To the extent that

cket vendors and their venue operator clients collect these fees for anything other than the

provision of “special services,” they would be in violaon of New York law. In addion, any of

these fees that exceed a “reasonable” charge are impermissible under the law.

42. Rather than collecting money through fees to the consumers, these companies collect money from sellers who use their

platforms to sell to consumers. We observed no consumer fees being charged on any of these companies’ websites, and indeed

Expedia and Priceline state they rarely charge broker fees to consumers.

32

C. Restraints of Trade in Tickeng

Up to this point, the Report has focused on the sale and brokerage of ckets, which are subject to

industry-specic regulaon under Arcle 25 of New York’s Arts and Cultural Aairs Law. However,

under the Donnelly Act, the Aorney General is also tasked with enforcing the laws prohibing

unreasonable restraints of trade and the unlawful monopolizaon of markets. Pursuant to that

authority, NYAG has serious concerns about several ongoing pracces related to the sale and

resale of ckets in New York. In parcular, NYAG is concerned with the seng of price oors on

cket resale, the pracces that impede consumer access to alternave cket resale plaorms,

and, in parcular, the combined eect of such conduct on consumers. NYAG is involved in an

ongoing mul-state invesgaon of these issues.

1. Seng of Ticket Resale Price Floors.

Some cket issuers – parcularly sports teams, including NFL teams and the New York Yankees

– have put in place “price oors.” Price oors are rules designed to prevent ckets from being

sold at a price below some level, usually the face value of the cket or something close to it.

For example, many NFL teams encourage or even require cket holders to use Ticketmaster’s

“NFL Ticket Exchange” plaorm – which is frequently billed as the ocial resale site and the

only “safe” place to buy secondary NFL ckets. However, on NFL Ticket Exchange the seller is

then prohibited from seng a price below a certain level – generally the face value of the cket.

Consequently, if a season cket holder wants to sell his or her ckets for a lower price than he

or she paid, he or she may be unable to do so, or may need to use a complex procedure to do so

on another plaorm.

NYAG’s concern with price oors is twofold. First, buyers of ckets on Ticket Exchange or other

sites with price oors are frequently not informed that the ckets they are buying are subject

to a oor. It is therefore easy for buyers to be fooled into believing what they are paying is the

market price for a cket, when in fact the buyer is paying a price arcially inated by a price

oor. The more aggressively sports leagues and individual teams push cket buyers and sellers

to use their “ocial” secondary markets, the more serious this problem becomes.

More fundamentally, even when buyers are informed of price oors, the oors deprive the

public of a chief benet of the market-driven approach taken by the 2007 law: lower prices. In

parcular, price oors may make it impossible to obtain ckets on the team-promoted Ticket

Exchange plaorm for below face value when demand decreases. As described above, when

contemplang the legalizaon of cket resale, the sponsors of the 2007 legislature repeatedly

expressed the hope that legalizing prot resale might lower prices for consumers. A clear source

of such savings is lower prices when demand falls. For example, near the end of an unsuccessful

baseball season, the ckets to watch a team not desned for the playos may go down sharply,

allowing fans who otherwise might not be able to aord to see a match to buy ckets for far less

money.

Overall, NYAG believes there is lile to say in favor of price oors: They tend to expose the public

to the full costs of the new cket economy, while depriving the public of the benets.

33

2. Pracces That Impede Consumer Access to Alternave or “Unocial”

Ticket Resale Plaorms.

The problems that come with price oors are exacerbated by eorts to push consumers to the

resale plaorms that maintain them and pracces that impede consumer use of plaorms that

do not. NYAG is therefore greatly concerned with other forms of restraints imposed on the resale

of ckets, parcularly when those restraints impede or complicate consumer access to resale

cket plaorms that do not enforce price oors. Examples of such pracces include delayed

delivery of PDF versions of resold ckets, and policies that place season cket holders at risk of

cancellaon of their cket subscripons when they sell on unocial resale plaorms.

The consumer harm caused by price oors is directly related to the success of the eorts to

pressure consumers to use only the primary seller’s (usually Ticketmaster’s) plaorm. That is

because plaorms that use price oors are at a natural compeve disadvantage compared to

those that do not, and so if consumers engage in comparison shopping, they will gravitate to the

plaorms with a more open market. However, to the extent that the combinaon of pracces

such as PDF-delays and cancellaon threats pressure consumers into using the plaorms that

incorporate a price oor, consumers will be harmed. This is parcularly true given the inadequate

disclosure of the existence of these price oors. Without knowing that beer prices could be

available elsewhere, it is harder for consumers to benet from the compeve market.

34

RECOMMENDATIONS

The State regards ckeng and cket resale as “a maer aected with the public interest.”

43

Unfortunately, if one of the purposes of the 2007 law – which repealed the ban on “scalping”

– was to reduce cket prices, or make ckets more available to “ordinary” fans, it has not been

successful. While there have been some posive developments, the basic reality described in the

1999 Report remains the same. If nine decades of experience have taught anything, it is that the

incredible demand for desirable ckets can be exploited even in the face of determined eorts

to get ckets in the hands of the public. The long history of cket “scalping,” the challenges

inherent in enforcement, and the incenves and prots available may make some think it is

impossible to x ckeng. Nonetheless, the situaon is not hopeless.

There are several concrete steps industry parcipants can take to make the system fairer and

more transparent. In light of the ndings in this Report, we believe that the legislature should

hold hearings on the subject of ckeng in New York to challenge key members of this industry

to put forth how they might help more ckets get into the hands of “ordinary” fans. However,

if soluons are not implemented soon, the best and cheapest ckets will connue to go to the

resellers and consumers will connue to ask why they cannot get ckets.

A. Ticket Resale Plaorms Must Ensure Brokers

Comply With the Law.