Authors:

Wanda Cabella

Mathias Nathan

Editors:

Esteban Caballero

Pablo Salazar

Lorna Jenkins

Daniel Macadar

© UNFPA/DEBORAH ELENTER

Challenges Posed

by Low Fertility in

Latin America

and the Caribbean

Latin America

and the Caribean

WORKING PAPER

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean

© UNFPA, 2018

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this document do not necessarily reect those of the United

Nations Population Fund.

1

This document presents a brief overview of the characteristics

of low and very low fertility regimes. In it we identify

the demographic challenges faced by the countries leading these changes,

together with the main public policies implemented to provide solutions

to the ensuing consequences. It likewise seeks to draw lessons

from the experience obtained in these countries that could be useful

for Latin America and the Caribbean.

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean2

Contents

Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................................3

What are low fertility regimes and how are they measured? ....................................................8

In what regions of the world do low fertility regimes prevail? .................................................9

What are the main demographic mechanisms that account for low fertility

regimes? ................................................................................................................................................................. 11

What are the main social, economic and cultural forces that explain the low

fertility regimes? ................................................................................................................................................13

Is low fertility a problem? ............................................................................................................................14

Is it possible to reverse very low fertility? ..........................................................................................15

What is the current situation in Latin America regarding replacement regimes? ...16

What is the impact of the sustained drop in adolescent fertility

in Latin America and the Caribbean on the total fertility rate? ...........................................18

Is it necessary to implement policies to prevent the decrease in fertility

to extreme levels? ............................................................................................................................................ 23

What policies have been implemented in countries that have experienced long

years of low fertility regimes? Which have been successful? .................................................23

What policies could be more adequate and more feasibly applied in LAC? .............. 25

References ..............................................................................................................................................................27

3

Introduction

According to a recent United Nations estimate -published

in World Population Prospects (2017) - nearly half of the

global population resides in countries affected by low

fertility, with 18 of these countries found in Latin America

and the Caribbean. The falling birth rate is the main factor

that explains these decreasing demographic trends,

the changes in population age structure, aging and the

subsequent pressure on social security systems.

The aim of this document is to facilitate a dialogue

regarding the fall of fertility levels and its implications

for our region. At the same time, it recognizes that low

fertility represents a challenge to societies’ development,

but should not be addressed as a threat. It is UNFPA’s

intention to highlight this issue and encourage countries

to adopt strategies allowing them to adequately manage

these realities and their possible impacts, among them

the nourishing of the creative and productive potential of

a society for all ages- empowering those of working age

while simultaneously creating more inclusive communities

which will allow those of a more advanced age to better

lend their experience and energy in ways which will bring

benefit across the board.

Detailed in this document are the common characteristics

of countries faced with low and very-low fertility, including

analysis of the history of those at the forefront of these

changes, the challenges they have faced and the initiatives

they have put into place to confront them. Also presented

are lessons learned which may be of relevant use in dealing

with the extreme fall of fertility in our region.

While acknowledging that the information presented

may not be suitable for general application, since local

particularities may require answers tailored specifically to

them, it is to be stressed that very low fertility can only be

avoided through promotion of certain incentives including,

but not necessarily limited to, childcare services, achieving

a work-life balance condicive to family planning, legislation

pertaining to maternity and paternity leave and a sharing

of domestic responsibilities between parents regardless

of gender which, in turn, is linked with the recognition

of women’s sexual and reproductive rights, and greater

participation of women in the labor market.

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean4

5

© UNFPA/DEBORAH ELENTER

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean6

© UNFPA/ESTEBAN CABALLERO

7

Challenges Posed by Low

Fertility in Latin America and

the Caribbean

In the last two centuries humanity has witnessed the

longest periods of population growth in history. Societies

and governments, therefore, have some experience in how

to face the consequences and eventual problems posed

by demographic growth. Current generations have not

known stages of deceleration of population growth of

the magnitude and stability recorded at present in much

of the developed world (Teitelbaum 2018). The birth

reduction is the main factor that accounts for the scant or

lack of population growth in more developed societies. The

reduction of fertility to low levels during extended periods,

slightly over thirty years in several European countries

and around two decades in some countries of East Asia,

has given rise to the concept of “low fertility regimes”. The

installation of these regimes has raised a certain level of

concern among some specialists and among the political

teams of countries where fertility has reached low and very

low levels. The eects of this trend on the age structure,

basically aging, together with the pressure exerted on the

social security system, the slowdown in population growth,

and even the possibility of its decline in absolute terms, are

among the most frequently used reasons mentioned when

drawing attention to the potential social and economic

harm caused by low fertility contexts. Reasons of nationalist

(related to the social identity of the populations) and

even military (related to the decline of potential military

personnel) nature have also been indicated, although as a

side-issue (Rindfuss and Kim Choe 2015).

The controversy surrounding the eects of falling fertility

has become increasingly sophisticated as more countries,

more or less developed, have entered into low fertility

regimes. With the increasing availability of information

and knowledge about the demographic mechanisms

involved in the recent decline, it is possible to reassess

the magnitude of the drop and its consequences, and

even observe how the dierent institutional and cultural

contexts react dierently to the fertility drop.

At the turn of the century, the countries of Latin America

and the Caribbean have begun to reach total fertility rates

in line with low fertility regimes, three or four decades later

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean8

than the countries that led this change. Although levels

are still heterogeneous, the truth is that in the past years

a signicant group of countries in the region converged

towards fertility levels at or below the level of generational

replacement (Cabella and Pardo 2014; ECLAC 2011). At

present, and according to recent United Nations estimates,

18 Latin American countries have Total Fertility Rates (TFR)

below the replacement level (United Nations 2017). So

far none of the Latin American countries has crossed the

limit of 1.5 children per woman (very low fertility), so the

region is in time to evaluate the possibility of fertility drops

below this level and advance solutions to the potential

problematic consequences associated with the extreme

fertility reduction. As will be seen later in this document,

there are relevant nuances among the demographic, social

and economic eects of the low fertility regimes and

those with very low or ultra-low fertility rates. For the

time being, suce it to say that there is a certain consensus

that the challenges posed by very low fertility regimes are

much more dicult to overcome, and that avoiding fertility

reductions that imply the installation of this type of regimes

is a rst lesson we can draw from the recent experience in

European and Asian countries (Morgan 2003). A second

lesson that emerges from the analysis of low fertility

regimes is that their arrival is inevitable and even desirable

as they usually are the result of greater gender equity,

almost perfect contraceptive control, more educational

and employment opportunities for women. A third lesson,

particularly relevant in developing countries, is that so far

low fertility regimes have become installed in countries that

count with the necessary resources to implement adequate

institutional measures to make parenting compatible with

the life-style of these societies (Morgan 2003).

With these two ideas in mind (acceptance of low fertility

and acknowledgment that it is possible to avoid extremely

low fertility) this document aims to: a) highlight the

characteristics of the low and very low fertility regimes, b)

review their evolution in countries leading these changes

together with the main demographic challenges faced, c)

review the policies implemented to meet the challenges

of low fertility and d) draw lessons from the experience in

these countries that could be useful in Latin America and

the Caribbean.

In order to organize information and facilitate its reading,

the document is structured as a set of questions related to

the evolution and characteristics of low fertility regimes,

the situation in Latin America and the Caribbean vis a vis

the recent decline in fertility close to or lower than the

replacement level, and nally in relation to the policies

adopted in the pioneer countries that could serve as a

reference for ours.

1. What are low fertility regimes

and how are they measured?

Low fertility regimes are those in which the total fertility

rate is below replacement fertility levels. Replacement

fertility is equal to the level of fertility which, if maintained

over time, will produce a zero-population growth under

the assumption of constant mortality and absence of

migration. The replacement level corresponds to a total

fertility rate of 2.1 children per woman, the rate that

ensures the replacement of the number of women of

reproductive age.

1

Thus, the long-term persistence of a

fertility rate below the replacement level would produce a

population decrease.

Countries with very low or extremely low fertility are

those that are below the threshold of 1.5 children per

woman (McDonald 2006, Rindfuss and Kim Choe 2016). The

threshold of a TFR of 1.3 children per woman has also been

used to describe the experience of several European and

East Asian countries that during the 1990s achieved the

lowest fertility levels known to date (Kohler et al., 2002;

Goldstein et al., 2009). Although arbitrary, the denition

1. It is greater than 2.0 because some girls do not manage to sur-

vive until the reproductive ages and due to the imbalance in the

relationship between newborn boys and girls, in favor of boys.

9

of these thresholds is useful to predict the rate of growth

and the long-term change in the population age structure.

A stable population (and with constant mortality rates)

with a TFR of 1.5, for example, would be reduced by half

in 64 years; with a TGF of 1.9, this would take 230 years

(Toulemon 2011).

The total fertility rate (TFR) is a synthetic period measure,

which expresses the number of children a woman would

have if she were subject throughout her life to the fertility

rates according to age observed during that moment or

period (usually a year). It is the most widely used indicator

to analyze the evolution of the fertility level of a population

given its availability for a broad set of countries and

years, and due to the relative simplicity to estimate it and

communicate results. As will be seen later, this measure is

not free from interpretation diculties, particularly during

periods of change in fertility.

Measures of cohort fertility, which follow the reproductive

experience of a generation, allow direct interpretation of its

value, and the number of children that a certain generation

of women had and at what ages may be unequivocally

estimated. The major problem is that it requires waiting

for each generation to complete its reproductive life. In

this document, we will not refer much to cohort measures,

which will be specically included to underscore the fact

that variations in period measures such as the TFG, for

example, do not strictly correlate with the nal cohort

fertility values.

2. In what regions of the world do

low fertility regimes prevail?

Fertility rates under the replacement level (low fertility,

very low or ultra-low fertility) have been a widespread

phenomenon in Europe since the 70s and a few years

later in several Asian countries. The unprecedented birth

rate increase after the end of World War II was followed in

most of these countries by a reduced fertility trend which

FIGURE 1.

NUMBER OF COUNTRIES WITH FERTILITY BELOW THE

REPLACEMENT LEVEL IN 20102015 IN SELECTED

REGIONS

Data source: United Nations, WPP 2017.

Number of countries

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

1950/ 1955/ 1960/ 1965/ 1970/ 1975/ 1980/ 1985/ 1990/ 1995/ 2000/ 2005/ 2010/

1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Europe Asia Latin America and the Caribbean

Period

led to the description of low and very low fertility regimes

as demographic scenarios that would characterize the

new dynamics of family formation in the most developed

countries. This phenomenon is known in the literature as

the passage from baby boom to baby bust.

Fertility has long fallen beyond the replacement level in

developed regions, and most of the countries included

form part of the post-transitional or low fertility group.

However, there is considerable variability: while some

countries have a TFR just below the replacement level,

others present values between 50% and 75% below the

replacement value (Rindfuss and Kim Choe 2016).

According to the recent United Nations estimates (United

Nations 2017), almost half of the world population lives in

low fertility countries. The number of countries with fertility

below the replacement level increased sharply in the past

four decades, going from less than ten in the early 1970s to

more than eighty at present (gure 1). Approximately half

of the low fertility countries are in Europe. This increase was

also registered, although later, in the Asia and Latin America

and the Caribbean regions.

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean10

The Southern Europe and Eastern Europe regions, as well

as East Asia, have the lowest fertility rates in the world,

with levels close to 1.5 children per woman on average

(gure 2). By manner of example, a TGF of 1.6 was observed

in Ukraine, 1.5 in Italy, 1.4 in Spain and 1.3 in Greece,

Portugal, and Poland during the 2010-15 period. Among

the countries with very low fertility in East Asia, we may

mention Japan (1.5) and South Korea (1.3). Fertility levels in

the regions of North-Western Europe are usually closer to

the replacement level: the TFR varies between 1.8 and 2.0

children per woman in countries such as Denmark, France,

Holland, Norway, United Kingdom or Sweden (United

Nations 2017). In some of these countries, TFR proximity to

the replacement level is linked to the implementation of

generous parental leaves, advances in child care coverage

and policies that encourage gender equity, among other

measures. We will later review the main policies associated

with fertility levels close to two children per woman.

Based on the experience observed in the more developed

countries, it may be said that until now there is no

theoretical or empirical “limit” in which the TFR stabilizes

once it is below the replacement level. On the contrary,

evidence in low fertility countries indicates that the TFR

tends to be unstable, and subject to changes in the labor

market and the economic situation, or to policy measures

addressed to families among other factors. These changes

often operate through the modication of the fertility

calendar, causing a rise or fall in births in a population in

a given year. On the other hand, the nal cohort fertility

tends to be more stable than period fertility and close

to replacement level (Sobotka 2017). Furthermore, the

instability and diversity of the TFR contrast with the relative

stability observed in the ideal family size in low fertility

countries, that is close to the two children (Sobotka and

Beaujouan 2014).

Similarly, the existing diversity in fertility rate among

developed countries suggests that there are institutional,

political, cultural and historical factors operating at the

national level. The eect of these factors varies among

countries and allows to explain the observed dierences

in fertility within the group of post-transitional societies.

This is central when considering the possible strategies to

reverse future fertility reductions (Rindfuss and Kim Choe

2016). One of the dierential aspects when comparing

these countries with countries in Latin America and Africa

is that adolescent fertility level is low, almost nil in some.

Even so, there also is variability in the adolescent fertility

rate among high-income countries. According to the data

reported in the Di Cesare report (2016) for Western high

income countries, in 2013 the Anglo-Saxon countries

(United States, United Kingdom and New Zealand) showed

the highest values (between 25 and 30 ‰ ), while the vast

majority of countries presented rates close to or below

10 ‰. Within the set of countries below this threshold,

there are some that stand out for their extremely low rates.

In Slovenia the rate is under 1 ‰, in Switzerland it is 1.7

‰, and several countries (Germany, France, Italy, Austria,

among others) are close to 4 ‰ rates. The report highlights

that the low current rates result from a sustained decline

process that started in the 1960s. More importantly, they

TFR

5.0

4.5

4.0

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

1970/ 1975/ 1980/ 1985/ 1990/ 1995/ 2000/ 2005/ 2010/

1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Western Europe Nothern Europe Southern Europe

Eastern Europe Eastern Asia

FIGURE 2.

EVOLUTION OF THE TOTAL FERTILITY RATE BETWEEN

197075 AND 201015 IN LOW FERTILITY SUBREGIONS

Data source: United Nations, WPP 2017.

Period

11

are the outcome of the implementation of consistent

policies over time geared to achieve substantial

improvements in adolescent sexual and reproductive

health.

3. What are the main demographic

mechanisms that account for low

fertility regimes?

Three demographic forces leading to the creation of stable

regimes of low and very low fertility have been recognized:

1) the choice of a small number of children (quantum) 2)

the postponement of the rst birth (tempo) and 3) the

increased proportion of women who do not have children

(childlessness).

As for the rst, it is important to note that in the most

developed countries the number of women or couples who

have many children is small; consequently, the proportion

of high-order births (3 or more) is very low: between 75 and

90% of births are currently rst or second order (Morgan

2003). Most couples choose to have few children, and this

standard seems to have installed in low fertility countries at

least half a century ago when developed societies reached

the last demographic transition phase.

The recent fall in fertility to low and very low levels in

these countries was mainly driven by the second factor

mentioned above: the delay in the fertility onset to a

more advanced age (Figure 3) which has meant that an

increasing number of women begin their reproductive

life over 30 years of age (Kohler et al., 2002). This process

is known as the Postponement Transition and explains

the importance of the changing fertility calendar in the

fertility drop to low and very low levels. The postponement

of fertility, fundamentally the rhythm at which it was

processed, caused periods of sharp fall of the TFR. The TFR is

aected by changes in the fertility calendar and the female

population distribution according to their parity, which

sometimes causes an equivocal interpretation of these

values (Bongaarts and Sobotka 2012). The postponement

of entry to motherhood among young cohorts, for

example, causes a decrease in births observed over a

period and correspondingly a lower TFR than that observed

in the absence of such a calendar change. In other words,

the delay in the fertility age produces a reduction in the TFR

during the period even if the nal cohort fertility remains

unchanged. This change in the period indicator caused by

variations in the fertility calendar is known as tempo eect

or distortion.

The so-called tempo eect has been a central element

accounting for the decline of the TFR to extremely low

levels in European countries during the 1990s; although

these countries have characteristics that explain having

reached low fertility, none of them would have reached

such extreme levels without the decisive pressure exerted

by the calendar eect (Goldstein et al., 2009).

The variability in the current TFR values between the low

and very low fertility countries is partly due to the “rebound

eect” registered in the great majority of the European

countries that pioneered the fertility decrease to low and

very low levels (Bongaarts and Sobotka, 2012, Bongaarts

and Feeney 2010). The process started in these countries

between the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, and the rate reached

very low values in some. However, in the 1990s period

fertility began to rise, and now the TFR tends to approach

the replacement threshold in several countries. The

demographic explanation for the recovery of the period

fertility level is attributed to the gradual disappearance of

the tempo eect, once the postponement of births ceased

to exert a lowering eect on the GFR.

Postponement to advanced reproductive ages can have

undesirable eects among women who start late (or

reach advanced ages of the reproductive cycle without

having children, but with the desire to have them) since

their time of exposure to the probability of being mothers

is shortened, and this in turn conditions these women’s

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean12

possibility of having the expected number of children.

Additionally, postponement to older ages increases the

likelihood that people will choose a life without children

or eventually lose interest in that option (Sobotka 2017).

The postponement of fertility has also resulted in couples

that decide to have children when women’s fertility is in

decline (Velde & Pearson 2002), with an increased risk

of prolongation of time to pregnancy, infertility, and

miscarriages, among other aspects related to maternal and

newborn health (Schmidt et al., 2012).

The third factor impacting on the consolidation of low

fertility regimes is the growing number of women who,

for various reasons, reach the end of their reproductive life

without having children. Although in all societies there

is a portion of the population that does not participate

in the process of biological reproduction, in recent years

the growth of nulliparity has been studied as a social and

demographic phenomenon characteristic of societies

undergoing Second Demographic Transition. In European

countries, even though nulliparity gures vary, there is a

convergence towards increased childlessness. At present

this value is approximately 20% among women who have

completed their reproductive cycle in Austria, Germany,

and Switzerland. Without reaching such high values, a

series of other European countries have likewise increased

the proportion of women who remain childless, with an

average value of 15% (Sobotka 2017). In very low fertility

Asian countries (Japan, South Korea, Singapore) this

indicator reaches gures close to 30%. It should be noted

that the registered values of childless women at the end

of their reproductive life oscillate between 5 and 10% for

most of the 20

th

century. The reasons for this phenomenon

are diverse, but there is some consensus that nulliparity

is partly an unintended consequence of postponement,

and largely the result of a deliberate choice of a child-free

lifestyle, or the outcome of having opted for personal

development and work and having to face the diculties

of combining work with upbringing (Kreyenfeld and

Konietzka 2017).

FIGURE 3.

MEAN AGE AT FIRST BIRTH IN SELECTED COUNTRIES. 1978 2011

Source: Our own, with data from the Human Fertility Database. www.humanfertility.org.

31

30

29

28

27

26

25

24

23

22

21

20

1978 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010

Japan

Holland

Spain

Sweden

Austria

Chzech

Republic

United

States

13

4. What are the main social,

economic and cultural forces that

explain the low fertility regimes?

Numerous transformations unfolded simultaneously

between the last decades of the 20th century and

the beginning of the 21st century and contributed to

modify reproductive behavior in Europe, especially

the postponement of the rst birth. Sobotka (2017)

summarized the factors indicated in several studies,

stressing the key role played by four factors in delayed

parenthood: 1) the expansion of education, 2) the

increasing economic uncertainty, particularly among young

people, 3) the gender revolution, which has mainly resulted

in the almost complete incorporation of women into the

labor market, and 4) the transformations that have taken

place in the sphere of couple relationships.

Underlying these changes we may recognize an

ideological-cultural change component, ultimately

expressed in the Second Demographic Transition concept.

Its main promoters, the Belgian demographers Lesthaeghe

and Van de Kaa (1986), argued that during last decades

of the 20th century a series of changes converged and

radically modied the role of individuals about both

family and society. According to these authors, the forces

of modernization led to an exacerbation of individualism

which, transferred to fertility decisions, meant that

individuals increasingly evaluated the cost of having

children in relation to the loss of their autonomy that

hindered their personal development and decreased their

© UNFPA/DEBORAH ELENTER

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean14

time for leisure. Individual autonomy and self-realization

are at the center of life course decisions, freedom of

choice and equal opportunities become highly valued life

goals; at social level laws are adopted to guarantee the

respect for personal decisions such as divorce, abortion

and reproductive decision making in general (Lesthaeghe

2014; Giddens 1993). In turn, the structural changes

accompanying the consolidation of the industrial and

post-industrial economy made working in the labor market

increasingly incompatible with child-rearing tasks.

None of these changes would have been possible without

three revolutions that began in the 1960s: the contraceptive

revolution, the sexual revolution and the gender revolution

(Giddens, 1993). The invention of highly ecient contraceptive

methods enabled a radical change regarding reproductive

decisions: “... during the First Demographic Transition, the issue

was to adopt contraception in order to avoid pregnancies: during

the Second Demographic Transition the basic decision is to

stop contraception in order to start a pregnancy “(Lesthaeghe

and Surkyn 2004). The invention the pill methods made it

possible to postpone the beginning of reproductive life until

the desired time without abstaining from sexual life and thus

allowed societies where contraception is the “default option”

to ourish (Balbo, Billari & Mills 2013). On the other hand, the

sexual revolution questioned the idea that sexual life was only

legitimate within marriage, together with the notion that its

sole purpose was procreation. According to Van de Kaa (2004),

fertility becomes “derivative”, and results from a long reection

process where the central question in this deliberation

regarding reproduction is: “will the arrival of a child contribute

to my self-realization? “. Finally, the gender revolution, with its

hallmark questioning of patriarchal power and connections

with the expansion of women’s education and employment,

has resulted in an unprecedented drive towards greater

autonomy of women when taking conjugal and reproductive

decisions. All these changes contributed in general terms to

delay the formation of couples and the arrival of the children.

5. Is low fertility a problem?

There is consensus according to which reduced fertility

results from the capacity of populations to meet their

reproductive objectives both regarding the number of

children and the time to have them. It would thus be

inappropriate to consider that low fertility is a problem per se.

Even so, its consolidation poses challenges for contemporary

societies that must tailor their institutions to adapt to the

new demographic reality. A low fertility sustained over time

leads to an aging population and an eventual negative

population growth. The lower the fertility rates, the faster

these changes will be processed. What are then the concerns

associated with aging and population decline?

With regard to the aging population, the main challenge

is associated with the nancial sustainability of social

security, public health, and elderly care systems. As older

people increase in number and the working-age population

decreases governments are faced with the problem of

nancing the cost of social protection systems and must

review the benets granted to people of retirement age and

the tax burden on the active population. Both options are

unpopular with the electorate and can generate political

costs for governments (Rindfuss and Min Choe 2015).

As for negative growth, concerns range from aspects

related to nationalism, the need to have a relatively large

domestic consumer market to place domestic economic

production and the challenge of sustaining the necessary

size of the country’s armed forces with young people

(Rindfuss and Min Choe 2015).

Low fertility is not a problem, and for some sectors may

even be positive as it lowers the burden for families,

and allows the possibility of achieving more equitable

societies from the gender standpoint if we consider that,

at least until now, it is basically women who are primarily

responsible child care. The fact that it is not a problem in

and on itself does not exempt societies with low fertility

demographic regimes from reecting upon its multiple

15

impact on social life, intergenerational and generational

relationships (the family network, for example, and with it

the supply for family care) and, fundamentally, to anticipate

its consequences when planning in relation to the negative

eects, particularly those derived from the labor market.

21

6. Is it possible to reverse very low

fertility?

The experience in European countries is a good example

of the role that the postponement of fertility can play

in the temporary decline of the TFR. A relevant part of

the explanation of the fall of the TFR to very low levels

responds to the “distortion” of the tempo eect that

generated the postponement of the rst birth in these

countries between 1980 and 2000, and its subsequent

recovery once the rate of increase of the deferment began

to slow down, that is, when the tempo eect ceased to

have signicant downward eects at period level. In sum,

from a purely demographic perspective, it is possible to

respond that very low fertility can be reversed insofar as

it is the outcome of a particular combination of intensity

and calendar, which, when diluted, causes the recovery

of period fertility. This rst explanation, of a mechanical

nature, is undoubtedly a relevant factor when weighing the

existence of a transient component in the fall to very low

fertility levels. As shown above in this document, this drop

to very low levels and its subsequent rebound has been

observed in several European countries. However, there still

is signicant heterogeneity in the TFR levels of European

countries and, generally speaking, of developed countries

that experienced drops to very low levels. Although it is

possible to interpret these dierences as dierences in the

rhythm of development of the Postponement Transition,

recent research has analyzed another set of factors, both

institutional and social, that help to explain why within the

set of countries that experienced drastic falls in fertility,

some returned to levels close to two children per woman

and others are still far from recovering a level close to the

replacement threshold.

As indicated by Morgan (2003), it is reasonable to consider

that “even large families will be small in the 21st century” as

a fact; this is consistent with two as the ideal number of

children in most of the low-income and very low fertility

countries (Testa 2006). However, in some countries the

TFR is currently very close to two children per woman

(France, Holland and Sweden) while in others it is much

less than two (Italy, Spain and Hungary, for example, have

TGF levels between 1.2 and 1.4). What factors explain these

dierences? What factors impacted in some countries to

make fertility recover while in others this recovery cannot

be even envisaged?

The more widely accepted theories on the decline of post-

transitional fertility agree that the expansion of female

education and the rise in women’s wages are powerful

drivers of the fertility reduction, as in the case of the

Second Transitional Demographic Theory (SDT) and the

New Home Economics (Aasve et al., 2015). However, recent

trends are showing that this relationship is not proven

in several countries of the developed world where the

relationship between development and fertility shows the

opposite sign to that expected according to the mentioned

theories: in several of the countries with a very advanced

SDT and with greater development fertility is increasing

rather than decreasing (Aasve et al 2015, Myrskyla et al

2009, Luci and Thévenon 2011).

Part of the explanation refers to the mechanics of the

TFR. But there a considerable debate is also starting in

relation to the role played by the emergence of increasingly

egalitarian societies in relation to gender roles. Between

the end of the 1990s and 2000s, Mc Donald (2000) and

Esping Andersen (2009) placed this issue at the center of

the discussion: the theory of the incomplete revolution

2. For a good analysis of the consequences of aging and the central

dimensions that must be addressed to avoid the diculties that

societies face due to the fall in fertility, see Rofman, Amarante and

Apella (2016)

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean16

posed by Esping Andersen and the theory of gender

equality mismatch in the public and the domestic spheres

are currently form the backdrop of the research that seeks

to unravel the reasons why some developed countries

increased their fertility and others did not.

Esping Andersen (2009) highlights the dierences in

fertility regarding the capacity of societies and institutions

to adapt to the new role of women in all areas of daily life,

and especially highlights the importance of the role played

by the state to make family and working life compatible

together with its eect on fertility. Mc Donald (2000)

interprets the dierences in post-transitional fertility

in relation to the specicities of the gender system in

countries with low fertility. A comparison between the

countries of Southern Europe (very low fertility) with

the Nordic countries (fertility close to replacement level)

shows that in the former there is a signicant gap between

gender equality in the institutions oriented to individuals

(education system, labor market) and gender relations

in the domestic sphere. In other words, gender equality

encourages fertility, if and only if there is a correspondence

between women’s opportunities in the public sphere and

an equal division of domestic roles. On the other hand, the

more the state ensures that family-oriented institutions

(e.g. childcare, parental and care leave, etc.) are based on

a foundation that promotes gender equality in the family,

domestic life, the fewer barriers couples will nd when they

decide to start or increase their fertility.

In summary, while the low fertility model is rooted in

developed societies where contributes towards gender

equality in all spheres of life, very low or ultra low fertility

regimes are associated with the existence of a gap in

gender equality when comparing the public and the

family spheres. In this sense, and to answer the question

that opens this section, there is consensus among experts

indicating that it is possible to reverse very low fertility and

that the key to avoid or reverse very low fertility regimes

lies in the construction of increasingly egalitarian societies

at the level of gender relations.

A varied set of measures was implemented in European

countries where the decline in fertility was signicant

and occurred since the mid-’70s, some explicitly aimed

at promoting births, others seeking to promote gender

equality and increasingly reconcile family life and work.

Spain, Sweden, and France (Pardo and Varela, 2013)

are three paradigmatic cases. There is a consensus that

countries, including Spain, that implemented policies

geared to boost the birth rate were hardly successful,

particularly those that did this through monetary incentives

(Thévenon 2011). France is an exception to this rule since

it is one of the countries that has managed to sustain a

TFR of 1.9 children per woman through comprehensive

family policies aimed to reconcile family and work, with a

signicant component of child care provision and a strong

dose of state co-responsibility. Sweden also has one of

the highest fertility rates in Europe, close to 1.9, but in this

country family policies never aimed to raise fertility but

rather to promote gender equality and especially involve

males in parenting tasks. A set of devices aimed to facilitate

the reconciliation between family life and work life was

implemented in both countries and included the public

provision of child care, parental leave, money transfers to

households, exible working hours and the promotion of

shared child care by men and women.

7. What is the current situation

in Latin America regarding low-

fertility regimes?

The Latin America and Caribbean region experienced a rapid

decline in fertility in the past decades. Several countries,

most of the from the Caribbean region (Table 1) present

a total rate below the replacement level, 18 countries in

the subcontinent reached a TFR under 2.1 children in the

2010-2015 ve-year period. In fact, the rst countries to cross

the replacement threshold in the 1980s were Antigua and

Barbuda, Barbados and Cuba. Later, some countries of South

America joined in together with Costa Rica.

17

Increased access to contraceptive methods is considered

a key factor accounting for the fertility drop in the region

(Guzmán et al., 2006). Nevertheless, the prevalence of

contraceptive methods in the region shows dierences

both among countries and social groups. The socially

most vulnerable sectors of the population have diculties

in accessing ecient methods and present a large gap

between their desired and eective fertility (Cavenaghi and

Alves 2009).

The fall in fertility to low levels in Latin America and the

Caribbean was not accompanied by the delay in the

fertility calendar as in the case of most European and

East Asian countries (Cavenaghi and Alves 2009; Sobotka

2017). Indeed, its uniqueness is due to the persistence

of a pattern of reproduction at early ages, particularly

during adolescence (ECLAC 2012, Cabella and Pardo 2014,

Rodríguez and Cavenaghi 2014).

The persistence of high adolescent fertility rates in

Latin America and the Caribbean responds, according

to Rodríguez (2013), to a combination of early sexual

debut, poor access to contraceptive methods since the

beginning of sexual life and limited access to abortion.

Likewise, fertility at early ages in the region occurs in a

context of strong inequalities in reproductive behavior

associated with the position occupied by individuals in

the social structure: people from low socioeconomic strata

usually have higher and earlier fertility than those in the

upper strata, as well as a higher proportion of unwanted

pregnancies (Cavenaghi and Alves 2009; ECLAC 2012;

Nathan, Pardo and Cabella 2016).

Some studies have shown the emergence of the

postponement of the rst birth, although basically

concentrated among the most educated women (Rosero-

bixby et al., 2009, Nathan 2015, Lima et al., 2017). This has

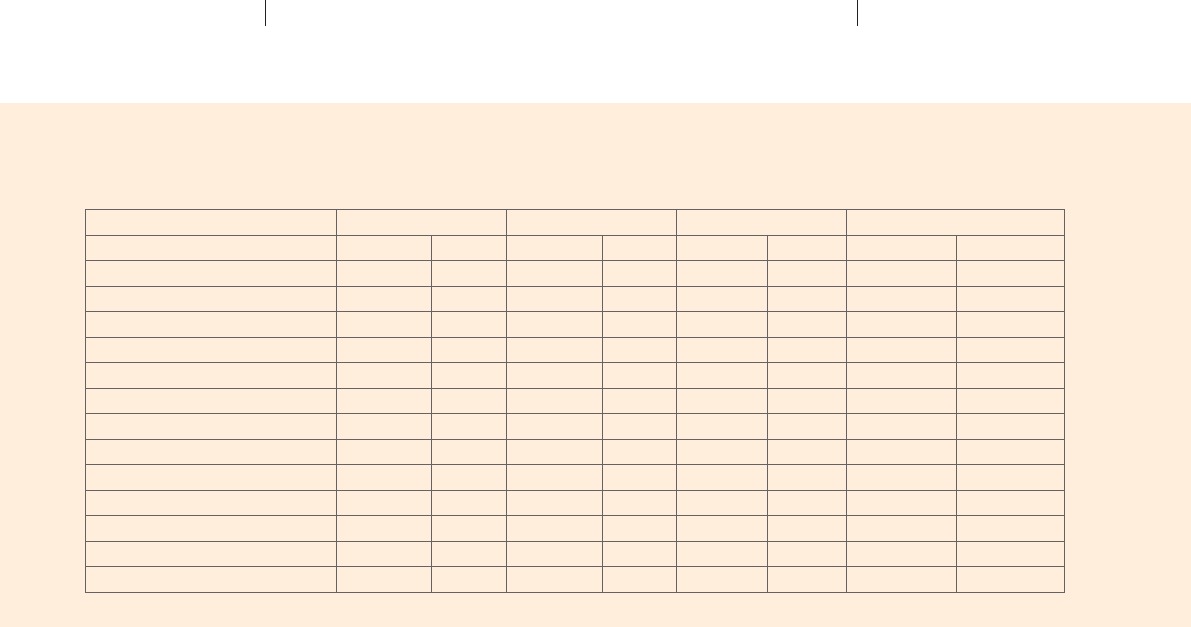

TABLE 1.

TOTAL FERTILITY RATE IN LATIN AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN COUNTRIES ACCORDING TO SUBREGION, 2010

2015

Caribbean Central America South America

St. Vincent and the Gren. 1.51 Costa Rica 1.85 Brazil 1.78

Puerto Rico 1.52 El Salvador 2.17 Chile 1.82

Cuba 1.71 Mexico 2.29 Colombia 1.93

Barbados 1.79 Nicaragua 2.32 Uruguay 2.04

U.S. Virgin Islands 1.80 Panama 2.60 Argentina 2.35

Aruba 1.80 Belize 2.64 Venezuela 2.40

Bahamas 1.81 Honduras 2.65 Surinam 2.46

Martinique 1.95 Guatemala 3.19 Peru 2.50

Guadeloupe 2.00 Equador 2.59

Trinidad and Tobago 2.01 Guyana 2.60

Curaçao 2.07 Paraguay 2.60

Jamaica 2.08 Bolivia 3.04

Antigua and Barbuda 2.10 French Guiana 3.45

Granada 2.18

Dominican Republic 2.53

Haiti 3.13

Data source: United Nations, WPP 2017.

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean18

produced a slow increase in the average age of women

when giving birth to their rst child in some countries such

as Chile and Uruguay (Nathan, Pardo and Cabella 2016, Lima

et al., 2017), together with an increase in the proportion of

women without children at 25-29 years in a broader set of

countries in the region (Rosero-Bixby et al., 2009, Esteve et

al., 2012). However, the growing contrast between the delay

in maternity of women with greater social and economic

opportunities and the persistence of an early fertility

among the most disadvantaged social sectors has caused a

polarization of the reproductive calendar (Rosero-Bixby et al.,

2009; ECLAC 2012; Rodríguez and Cavenaghi 2014; Nathan

2015; Lima et al., 2017). For this reason, it may be reasonable

to think that progress towards a late fertility context

develops slower in the region as compared to the experience

observed in developed countries.

Although fertility is expected to decline until it consolidates

at low levels close to 1.7 children per woman in 2050

(United Nations 2017), a certain margin of uncertainty

persists regarding the future course of reproductive

dynamics in Latin America and the Caribbean. In the

context of strong reproductive gaps between social sectors,

a high number of unplanned pregnancies (Sedgh et al.,

2016) and high rates of adolescent fertility, the possible

trajectories in terms of declining fertility level could present

a diversity of formats and rates of change.

8. What is the impact of the

sustained drop in adolescent

fertility in Latin America and the

Caribbean on the total fertility rate?

The main feature of the recent fertility drop in the

region has been the decoupling of the rate of decline in

adolescent fertility in relation to fertility at all ages. The

behavior of adolescent fertility will therefore play a decisive

role in the future evolution of the fertility rate in Latin

America and the Caribbean.

To what extent is this feature a specicity that may be

reversed with adequate reproductive health programs, or

is it a structural feature that is more dicult to combat?

Evidently the answer is not simple and the trajectories we

may envisage are diverse. This document considers the

United Nations projections as a standard source for the

analysis of prospective fertility scenarios in the region,

so in this section we will use them to describe the most

plausible future evolution of fertility in each country in

Latin America and the Caribbean, and for the region as a

whole. In this case we analyze the United Nations estimates

and projections (revision 2017, between the 2010-2015

and 2045-2050 ve-year periods) of the specic fertility

rates according to age together with total fertility gures,

with special consideration regarding the evolution of

adolescent fertility and its potential impact on the rates of

the immediately superior ages.

Figures 4a and 4b show the evolution of adolescent and

total fertility for Latin America and the Caribbean up to

the 2045-2050 quinquennium. We considered the three

projection variants used by the United Nations (high,

medium and low) and a fourth variant keeping the total

fertility rate constant at replacement level. According to the

projection data it is expected that adolescent fertility in the

region will continue with the downward trend observed in

recent years. A signicant reduction in the rate of age group

15-19 observed in 2010-2015 (67 per thousand) is expected

in the four variants. According to the medium variant,

the adolescent fertility rate would drop more than a half,

reaching a value of 32 per thousand. On the other hand,

the dierent variants predict total fertility rate passing from

2.14 children per woman observed in 2010-2015, to 2.26

(high), 1.77 (average) and 1.27 (low) in 2045-2050. Unlike

the trend registered in recent years, the graphs show a

more pronounced drop in the adolescent fertility than in

the total fertility rate. The model adopted by the United

19

Nations to project fertility thus reverses the main feature of

the recent reduction in Latin American fertility, namely, the

much faster fall in general fertility than that of adolescent

fertility (Rodríguez 2014; Cabella and Pardo 2014, ECLAC

2012). The United Nations projection even anticipates

the reduction of adolescent fertility also in a theoretical

scenario of constant fertility at replacement level.

The decrease in adolescent fertility is contemplated in

the changing pattern of fertility according to age, which

indicates that the evolution of total fertility will result from

two trends: a) a reduction of births in women at an early

age; and b) an increase in births at ages associated with

the postponement of motherhood (25-29 and 30-34 years).

This low and late fertility model approaches that observed

in European countries, and may be seen as the emerging

reproductive pattern in Latin America for the coming years.

It is worth mentioning that the adolescent fertility rate is

below 20 per thousand on average in the most developed

regions of the world. In Europe, it is currently at values close

to 18 per thousand, and around 26 per thousand in North

America (United Nations 2017). Having reached such low

early fertility values in the more developed regions does

not necessarily imply that the gaps between the social

sectors have been completely overcome. They persist,

and in some cases, there has even been an increase in the

dierences between the probability of having a child at

adolescent ages among women with higher and lower

FIGURES 4A Y 4B.

PROJECTED EVOLUTION OF ADOLESCENT AND TOTAL FERTILITY IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN,

19901995 TO 20452050

Data source: United Nations, WPP 2017.

100,0

90,0

80,0

70,0

60,0

50,0

40,0

30,0

20,0

1990 - 1995

1995 - 2000

2000 - 2005

2005 - 2010

2010 - 2015

2015 - 2020

2020 - 2025

2025 - 2030

2030 - 2035

2035 - 2040

2040 - 2045

2045 - 2050

Adolescent Fertility Rate (thousand)

Adolescent Fertility Rate

High

Replacement

Low

Medium

1990 - 1995

1995 - 2000

2000 - 2005

2005 - 2010

2010 - 2015

2015 - 2020

2020 - 2025

2025 - 2030

2030 - 2035

2035 - 2040

2040 - 2045

2045 - 2050

Total Fertility Rate

3,5

3,0

2,5

2,0

1,5

1,0

Total Fertility Rate

Low

Medium

Replacement

High

FIGURE 5.

RELATIVE DISTRIBUTION OF THE FERTILITY RATES

ACCORDING TO AGE GROUP IN LATIN AMERICA AND

THE CARIBBEAN, 20102015 AND 20452050

Data source: United Nations, WPP 2017.

30%

25%

20%

15%

10%

5%

0%

15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49

Age Group

2010 - 2015 2045 - 2050

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean20

FIGURES 6A, 6B, 6C, AND 6D.

EVOLUTION OF FERTILITY RATES ACCORDING TO AGE GROUP IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN IN THE

DIFFERENT SUBREGIONS, 19901995 TO 20452050

Data source: United Nations, WPP 2017.

180,0

160,0

140,0

120,0

100,0

80,0

60,0

40,0

20,0

1990 - 1995

1995 - 2000

2000 - 2005

2005 - 2010

2010 - 2015

2015 - 2020

2020 - 2025

2025 - 2030

2030 - 2035

2035 - 2040

2040 - 2045

2045 - 2050

Latin America and The Caribean

20-24

Family rates (in thousands)

25-29

30-34

35+

15-19

180,0

160,0

140,0

120,0

100,0

80,0

60,0

40,0

20,0

1990 - 1995

1995 - 2000

2000 - 2005

2005 - 2010

2010 - 2015

2015 - 2020

2020 - 2025

2025 - 2030

2030 - 2035

2035 - 2040

2040 - 2045

2045 - 2050

The Caribean

20-24

Family rates (in thousands)

25-29

35+

15-19

30-34

180,0

160,0

140,0

120,0

100,0

80,0

60,0

40,0

20,0

1990 - 1995

1995 - 2000

2000 - 2005

2005 - 2010

2010 - 2015

2015 - 2020

2020 - 2025

2025 - 2030

2030 - 2035

2035 - 2040

2040 - 2045

2045 - 2050

Central America

20-24

Family rates (in thousands)

25-29

30-34

35+

15-19

180,0

160,0

140,0

120,0

100,0

80,0

60,0

40,0

20,0

1990 - 1995

1995 - 2000

2000 - 2005

2005 - 2010

2010 - 2015

2015 - 2020

2020 - 2025

2025 - 2030

2030 - 2035

2035 - 2040

2040 - 2045

2045 - 2050

South America

20-24

Family rates (in thousands)

25-29

30-34

35+

15-19

educational levels (Raymo et al., 2015). In any case, these

dierences are noticeably lower than those observed

among dierent educational levels in Latin America.

In the transition towards a late fertility pattern, the fall in

fertility between 15-24 years will be compensated by a less

pronounced decrease in the births of mothers between

25 and 39 years of age, and even by a slight increase at

some of these ages. The evolution of specic fertility rates

by age group according to the United Nations projections

(medium variant) suggests a “rebound” in fertility in the

30-34 years group, and a stability of the specic rates in

the 25-29 years and 35+ groups in all subregions of the

continent (graphs 6a, 6b, 6c and 6d). It is worth mentioning

that the specic rates for older women vary both due to

the eect of the age of onset of fertility and the size of

the nal ospring. Thus, in parallel with the reduction in

quantum fertility, it is expected that the intensity at late

ages will experience a decrease since it is at those ages

that high-order births usually occur. But while the decrease

in high-order births tends to reduce rates at late ages of

the reproductive cycle, the postponement of the onset

of maternity acts in the opposite direction, slowing down

the rate of decline in fertility intensity at those ages or

even reversing it. This particular conuence of tendencies

between intensity and calendar is at the basis of the

assumptions used by the United Nations in agreement

with the trends of projected fertility according to age; it

may, therefore, be inferred that its technicians expect Latin

America to converge in the medium term towards a pattern

21

FIGURE 7.

TOTAL FERTILITY AND ADOLESCENT FERTILITY RATE IN SELECTED LATIN AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN

COUNTRIES, 20102015

Data source: United Nations, WPP 2017.

Note: The blue bars correspond to values for Latin America and the Caribbean

120,0

100,0

80,0

60,0

40,0

20,0

Adolescent fertility rate

(per thousand)

Brazil

Colombia

Costa Rica

Cuba

Chile

Uruguay

Jamaica

México

Argentina

Perú

Guatemala

Dominican

Republic

Total fertility rate

1.50 1.70 1.90 2.10 2.30 2.50 2.70 2.90 3.10 3.30 3.50

similar to that of the Postponement Transition observed in

Europe.

Twelve countries were selected according to the criteria

of regional and demographic representation (gure 7) to

review in greater detail the future scenario of fertility in the

region. These countries show a relative heterogeneity in the

evolution of adolescent and total fertility. In any case, we

sought to prioritize the analysis of countries with a TFR below

the regional average (below the replacement threshold) to

focus on the prospective analysis in low fertility contexts. In

most of these countries, the adolescent fertility rate ranges

between 50 and 70 per thousand, except Guatemala (80 per

thousand) and Dominican Republic (100 per thousand).

Table 2 shows the adolescent and total fertility rate in

selected countries for the 2010-2015 and 2045-2050 ve-

year periods, the percentage change of both indicators

between these two periods and the relative weight of

adolescent fertility levels in the total fertility rate. A general

reading of this table demonstrates that while a signicant

fall in adolescent fertility is expected, total fertility will show

a much less pronounced fall, suggesting that the pattern of

change in Latin American fertility rests on the assumption

that the fertility decline at early ages will be correlated

with a brake on the fall or possible increase in reproductive

intensity at older ages. In other words, that adolescents will

postpone the beginning of motherhood and that possibly

a portion of young women will move forward the rst birth.

According to this rationale, it is expected that the percentage

of TFR corresponding to the 15-19 years group will decrease

in all countries. The relative weight loss of adolescent fertility

will be much greater for those reaching the lowest total

fertility rates.

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean22

In a scenario of declining adolescent fertility in Latin

America and the Caribbean, it is ultimately plausible that

the total fertility rate will be below the replacement level,

but without reaching extremely low values. This would

occur under the assumption of a progressive consolidation

of a late fertility model in a region where women postpone

births, an expected transition in a low fertility context.

However, the fertility level projection does not include the

distortions that might be observed in the TFR due to the

rate of change in the average age of fertility (tempo eect).

If that were so, the TFR could experience periods of sharp

fall to very low levels, together with greater uctuations

associated with conjunctural factors. These potential drops

should be interpreted with extreme caution if we recall

the European experience that allows us to conclude that in

these the reductions are generally temporary, and do not

translate into drops of similar magnitude in the lifetime

fertility of the cohorts.

It is particularly important to consider this eect on

the TFR level. When women (or couples) change their

preferences and postpone the start of their reproductive

life, the intensity of fertility is aected downwards;

nevertheless, the nal fertility eventually may not change.

Put in demographic jargon, period fertility falls, but

cohort fertility remains unchanged. This occurs because a

sustained change in the reproductive calendar aects the

level of fertility observed each year. Let us use the example

of a population in which women have two children on

average: the rst usually at 19 years of age and the second

at 22, and, for whatever reason, there is a change in the

reproductive behavior in that population and women

postpone the rst birth to 25 years and the second at 28. In

the long term, cohorts that have children while processing

that change will have the same number of children, only

that they will have them later; the fertility of these cohorts

will not change but while the postponement is being

processed there will be a period during which there will be

missing births, so that the fertility of that 6 year period will

be lower than it would have been in the absence of that

postponement of fertility.

TABLE 2.

TOTAL AND ADOLESCENT FERTILITY RATES IN SELECTED LATIN AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN COUNTRIES, RELATIVE

CHANGE AND PERCENTAGE OF ADOLESCENT FERTILITY IN TOTAL FERTILITY, 20102015, AND 20452050

2010-2015 2045-2050 Relative Change %15-19 over TFR

15-19 TFR 15-19 TFR 15-19 TFR 2010-2015 2045-2050

Latin America and the Caribbean 66.6 2.14 32.0 1.77 -52% -17% 16% 9%

Argentina 64.0 2.35 41.1 1.93 -36% -18% 14% 11%

Brazil 67.0 1.78 30.0 1.63 -55% -8% 19% 9%

Chile 50.4 1.82 21.6 1.73 -57% -5% 14% 6%

Colombia 57.7 1.93 16.5 1.67 -71% -14% 15% 5%

Costa Rica 59.1 1.85 25.4 1.68 -57% -9% 16% 8%

Cuba 50.6 1.71 15.6 1.76 -69% 3% 15% 4%

Dominican Republic 100.6 2.53 51.0 1.84 -49% -27% 20% 14%

Guatemala 78.6 3.19 39.1 2.06 -50% -35% 12% 9%

Jamaica 60.8 2.08 20.7 1.77 -66% -15% 15% 6%

Mexico 66.0 2.29 29.2 1.72 -56% -25% 14% 8%

Peru 52.1 2.50 24.0 1.84 -54% -27% 10% 7%

Uruguay 58.0 2.04 29.2 1.82 -50% -11% 14% 8%

Data source: United Nations, WPP 2017.

23

9. Is it necessary to implement

policies to prevent the decrease in

fertility to extreme levels?

The answer to this question is yes if we are speaking of

societies unable to provide friendly environments for

the realization of the reproductive aspirations of the

population, which, as discussed earlier in this document,

are related to how widespread is gender equality in these

societies. To the extent that the breadwinner system is

increasingly less representative of the situation of families

– surely in the developed world, although its decline is

also undeniable in less developed societies - the dual

contributor model creates diculties when trying to

solve conicts between work and parenting tasks, and

specically overburdens women with the responsibility in

the absence of models of shared responsibility between

the state, the market and families and between men and

women.

If fertility in the region gets to the point of reaching long

periods of very low levels, as in European countries, it will

bring about an accelerated population aging together with

a smaller workforce, and surely demand that governments

reconsider social and family policies (or evaluate the

consequences of not having them). One of the risks

entailed in a poorly informed assessment of the fall in

fertility is the implementation of pro-natalist policies.

These policies are linked to the changing role of women in

the family. The reproductive aspirations of the population

are conditioned by several factors, where the cost of raising

children is central. Policies that aim to create more friendly

environments for fertility contemplate the trajectory of

women in the public sphere and the burden of care that

usually befalls them when they have children. In short, they

seek to contribute to make the “second shift “ (women’s

second shift) that refers to the domestic chores that women

usually perform after their workday, become a shared

responsibility together with other players, domestic and

non-domestic.

Broadly speaking fertility policies may be divided into

control, pro-natalist or work-family reconciliation policies

(linked to the notion of co-responsibility). The latter

does not have a demographic goal proper; however, by

attempting to achieve greater harmonization between

family tasks and paid work, they may remove pressure from

the burden of having children and therefore result in an

increased number of children.

Within this last policy package, it is possible to distinguish:

1) direct economic transfers; 2) parental leaves; 3) care

support; 4) exible jobs. None is optimal, and all have their

pros and cons. For this reason, it is often said that it is most

convenient for governments to develop a set of measures

and not implement one single policy. On the other hand,

decisions of this nature require a strong public investment,

either through the direct execution of services or the

economic subsidy to companies or families; the debate

also regards the relevance of such investment if the result

of these policies is minimal or nil in terms of modifying

reproductive behavior (if governments have established

future goals in this regard). On the other hand, the

combination of a varied menu of policies that remain over

time usually shows positive eects. According to recent

assessments, a stable supply of programs is one of the most

relevant aspects (Gauthier 2015).

10. What policies have been

implemented in countries that

have experienced long years of low

fertility regimes? Which have been

successful?

Concern about the undesired eects of the consolidation of

low and very low fertility regimes has been at the center of

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean24

the debate on the eects of demographic change in several

regions of the world for some years now. Many countries

have implemented policies to counter them. Low and

very low fertility regimes are observed in countries with

very dierent institutional structures and welfare regimes

(McDonald, 2006); the variety of measures is also relatively

important.

Although several authors point out the diculty of

evaluating the eects of family policies (Gauthier, 2015,

Thévenon and Gauthier, 2011) and even show that for the

most part, the eects are either ambiguous or marginal,

there are indications that some policies are more eective

than others.

As shown above, one of the explanations with more

consensus in relation to what makes the dierence

between the countries with very low fertility and those that

remain in low fertility regimes, regards the inconsistency

between gender equality in the public sphere (especially

the labor market) and in the domestic ambit (McDonald,

2000; Esping Andersen, 2013). In countries where domestic

gender roles have not changed in line with the changes

towards greater gender equality in other spheres, women

prefer to give up motherhood to avoid compromising their

careers or postpone it to extreme ages of reproductive life.

In these countries there is usually also little investment in

early childhood care, and the caring tasks fall upon the

family and especially women.

European countries have increased eorts to improve

family policies in the last two decades. Ireland, the United

Kingdom and Iceland, for example, raised their investment

in these policies between 2001 and 2009, reaching close to

4% of the GDP in 2009. Most investment in family policies

focuses on maternal, paternal and parental leave, together

with early childhood care services. Among these measures,

we highlight the leave periods strictly reserved for fathers

to promote the participation of men in caring tasks,

encourage gender equality in child care, as well as achieve

greater involvement of men with their children (Thévenon

et al., 2014). Another set of measures seeks to promote the

articulation between family public policies and measures

that depend on employers; the latter seek to increase

awareness in employers so that they contribute with work

schedules that help to manage family life and relieve

tensions between family and job. One of the challenges of

these policies is to achieve exible hours without exerting a

negative impact on working conditions.

In sum, the European experience shows that it is possible

to sustain fertility rates close to replacement levels without

necessarily aiming at demographic objectives. Although

there is controversy as to which mechanisms promoted the

increase in fertility (leaving aside the purely demographic

tempo eects), there seems to be a certain consensus that

gender equality in the domestic and public spheres plays a

key role to help people meet their reproductive aspirations

and that rather than monetary transfers, it is the measures

aimed at providing quality care services and enhance time

management that facilitate parenting tasks.

Family policies are increasingly a key instrument to

ensure that women and men succeed in making work

compatible with family, their role is also crucial to limit

the negative consequences of fertility on the well-being

of people and households (Sobotka 2017). This author

concludes that until now pronatalist programs, generally

based on nancial incentives, fail because they are not

able to integrate the new reality of gender relations and

the growing aspirations of women in the realization of

their working careers in the normative basis of policies.

On the other hand, even in countries that have managed

to mitigate gender discrimination in the labor market, this

aspect continues to be a barrier that must be overcome

by a signicant number of women. A recent paper by

Marianne Bertrand (2018) eloquently shows how women,

especially those with better payed jobs, face the so-called

glass ceiling, increasingly linked to penalties in the labor

market due to demands for exibility in working hours to

manage to harmonize family and work.

25

11. What policies could be more

adequate and more feasibly

applied in LAC?

In societies with high levels of inequality and where

“contraception by default” is not the norm, as is the case

for Latin American countries, it is hard to establish a set of

eective measures for the population as a whole. Is it, for

example, more convenient to invest in universal policies or

in targeted policies capable of addressing the most urgent

demands of the population, but positioned at social scale?

When thinking about family policies, we nd an additional

element: do we want to reduce the fertility of the poorest

and increase that of the most educated? Do we want

to reduce fertility at an early age but ensure that more

educated women do not postpone the rst birth to very

old ages? Do we want to achieve low adolescent fertility

but without a greater drop in total fertility? Is it necessary

to think of policies for dierent social groups? More

importantly, should we think that policies must accompany

the specicities and social realities of the dierent sub-

regions in Latin America and the Caribbean?

This document does not aim to anticipate a possible

answer to these questions, its purpose is to present the

© MARIA FLEISCHMANN

Challenges Posed by Low Fertility in Latin America and the Caribbean26

main challenges that Latin American societies face vis a vis

the demographic changes that have occurred and those

that will soon come. The overview of the measures adopted

by the countries that have processed changes of a similar

nature in the recent past aimed to give a general idea of the

more eective possible interventions at public policy level,

more in line with respect for reproductive rights and the

promotion of gender equality in terms of the biological and

social reproduction of populations.

According to a recent report by the International Labor

Organization (2009), even though the Latin American

region has progressed in the regulation of maternity

protection (maternity leave, for example), the beneciary

population is ultimately small, in particular, because

measures are exclusively linked to the formal labor market.

The report likewise highlights the fact that the legal

framework and policies aimed at reconciling family and

work life are still poorly developed and, more especially,

the scarce promotion of the involvement of men in

domestic and caring responsibilities. In short, the advances

are not proportional to the huge changes that have

occurred in women’s lives, especially in relation to their

massive participation in the labor market. The expansion

of coverage of educational services and care for young

children is underscored in the report as one of the most

important advances regarding work-family reconciliation,

although again, these policies are only commencing and

fragmentary.

27

References

- Aassve, A., Mencarini, L & Sironi, M. “Institutional Change, Happiness, and Fertility”,

European Sociological Review, Volume 31, 6(1): 749–765.

- Balbo, N. Billari. F. & Mills, M. (2013) “Fertility in Advanced Societies: A Review of Research”, Eur J Population (2013)

29:1–38.

- Becker, Gary S. 1965. “A Theory of the Allocation of Time.” The Economic Journal 75:493-517.

—. 1981. A Treatise on the Family: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

- Bertrand, M. (2018) – “The Glass Ceiling”, Coase Lecture Booth School of Business, University of Chicago, Economica, 85:

205–231

- Bongaarts J. and Sobotka T. (2012) “A Demographic Explanation for the Recent Rise in European Fertility”, Population

and Development Review, 38(1): 83–120.

- Bongaarts, J. y Feeney, G., “When is a tempo eect a tempo distortion?”, Genus, 66,2 1-15, 2010.

- Cabella, W. and Pardo, I. (2014) “Hacia un régimen de baja fecundidad en América Latina y el Caribe, 1990-2015”. In

Cavenagui, S. and Cabella, W., Comportamiento reproductivo y fecundidad en América Latina: una agenda inconclusa,

pp. 13-31, Alap Editor, Rio de Janeiro, serie e-investigaciones n°3. Available in: http://www.alapop.org/alap/Serie-E-

Investigaciones/N3/Capitulo1_SerieE-Investigaciones_N3_ALAP3.pdf, 2014.

- Cepal (2011) Panorama social de América Latina 2011, ECLAC, Santiago de Chile.

- Di Cesare, M.C. (2015) Fecundidad adolescente en los países desarrollados. Niveles, tendencias y políticas. LC/W.660,

Naciones Unidas: Santiago de Chile.

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 2009. The Incomplete Revolution: Adapting to Women’s New Roles.

Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gauthier (2015)

- Giddens, A. 1993. La transformación de la intimidad. Sexualidad, amor y erotismo en las sociedades modernas. Cátedra.

- Goldstein, J., Sobotka, T. and Jasilioniene, A. (2009). The End of “Lowest-Low” Fertility? Population and Development

Review, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 663-699.

- Guzmán, J.M., Rodríguez, J., Martínez, J., Contreras, J.M. and González, D. “The Demography of Latin America and the