Migration Policy Regimes 1

Human Mobility Governance Series

Migration Policy

Regimes in Latin

America and the

Caribbean

Immigration, Regional Free

Movement, Refuge, and

Nationality

Migration Policy Regimes 2

This project was carried out under the overall coordination of Felipe Muñoz, head of the Migration

Unit, by Diego Acosta, professor of migration law at the University of Bristol and consultant to the

IDB Migration Unit, in collaboration with Jeremy Harris, specialist at the Migration Unit. The following

experts assisted with the coding of the data on the various countries included in the project: Ignacio

Odriozola, Laura Sartoretto, María Eugenia Moreira, Luuk van der Baaren, and Alexandra Castro. Mauro

de Oliveira provided support with organizing the database and developing the online analytical tools.

Juan Camilo Perdomo and Kyungjo An helped review the database. The authors are grateful to José

Ignacio Hernández and two anonymous referees for their comments on the text.

Cataloging-in-Publication data provided by the

Inter-American Development Bank

Felipe Herrera Library

Acosta, Diego.

Migration policy regimes in Latin America and the Caribbean: immigration, regional free movement, refuge, and

nationality / Diego Acosta, Jeremy Harris.

p. cm. — (IDB Monograph ; 1010)

Includes bibliographic references.

1. Immigrants-Latin America-Social conditions. 2. Emigration and immigration law-Latin America. 3. Immigrants-

Latin America-Labor market. 4. Immigrants-Latin America-Economic aspects. 5. Naturalization-Latin America.

I. Harris, Jeremy. II. Inter-American Development Bank. Migration Unit. III. Title. IV. Series.

IDB-MG-1010

JEL Codes: F22, F66, H11

Key Words: Migration, Regularization, Access to Labor Markets, Citizenship, Migrants’ Rights.

Copyright © 2022 Inter-American Development Bank. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons IGO 3.0 At-

tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives (CC-IGO BY-NC-ND 3.0 IGO) license (https://creativecommons.org/licen-

ses/by-nc-nd/3.0/igo/legalcode) and may be reproduced with attribution to the IDB and for any non-commercial

purpose. No derivative work is allowed.

Any dispute related to the use of the works of the IDB that cannot be settled amicably shall be submitted to arbi-

tration pursuant to the UNCITRAL rules. The use of the IDB’s name for any purpose other than for attribution, and

the use of IDB’s logo shall be subject to a separate written license agreement between the IDB and the user and is

not authorized as part of this CC-IGO license.

Note that link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the license.

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the

Inter-American Development Bank, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent.

Note: The data presented in this study is valid as of December 31, 2021.

Migration Policy Regimes 3

By Diego Acosta and Jeremy Harris.

Migration Policy Regimes in

Latin America and the Caribbean

Immigration, Regional Free Movement,

Refuge, and Nationality

Migration Policy Regimes 4

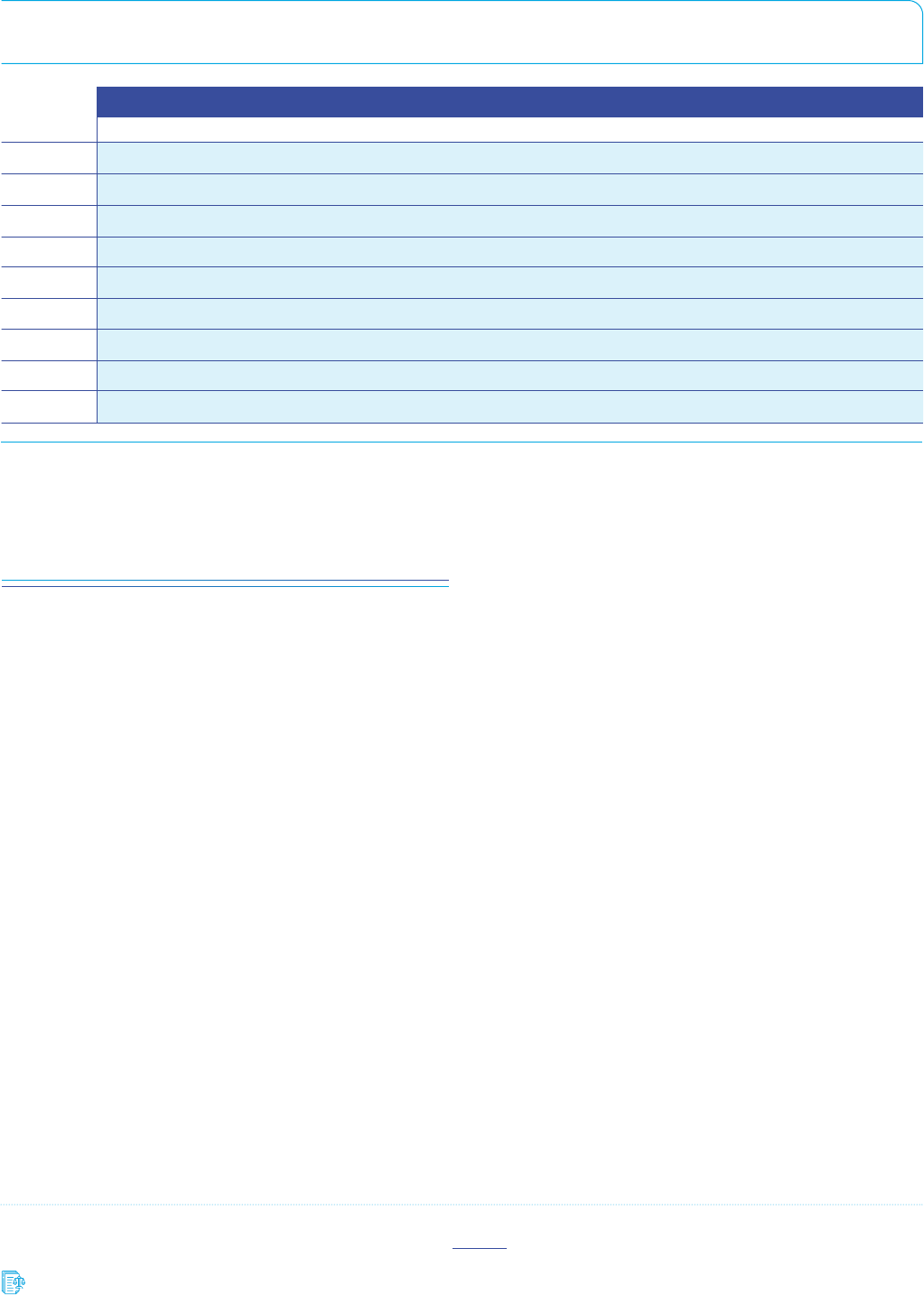

CONTENTS

Executive Summary 6

Introduction 8

1. International Instruments 10

1.a Main international United Nations human rights treaties 10

1.b International treaties that aect the regulation of human mobility 13

1.c Instruments that are not international treaties 14

Findings relating to international instruments 16

2. Regional Instruments 18

2.a Regional conventions 18

2.b Other indicators for regional cooperation 18

2.c Subregional instruments on the free movement of persons 19

Findings in regional instruments 21

3. Visa-Free Entry 22

4. Temporary Residency 25

4.a Preferential access to temporary residency 25

4.b Permanent regularization mechanisms 28

4.c Extraordinary regularization programs 29

5. Rights While Resident 31

5.a Right to work 31

5.b Right to healthcare 31

5.c Right to education 35

5.d Right to family reunification 35

5.e Right to permanent residence 36

5.f Right to vote 38

Migration Policy Regimes 5

CONTENTS

6. Nationality 40

6.a Jus soli (the right to citizenship for those born in the territory of a country) 40

6.b Jus sanguinis (the right to citizenship for children of nationals born abroad) 40

6.c Dual nationality 41

6.d Naturalization 46

7. Analysis of the Catalog of Migration-Related Legal Instruments 47

8. Conclusions 50

References 51

Annex I. Glossary 53

Annex II - Methodology 55

Annex III – Country Data 62

Migration Policy Regimes 6

Executive Summary

This report presents and describes a new database

that was generated using 40 indicators that typi-

fy the migration regimes of 26 countries in Latin

America and the Caribbean (LAC) that are borrow-

ing members of the Inter-American Development

Bank (IDB). These indicators have enabled us to

compare these migration regimes along multiple

dimensions, identify subregional patterns, and ob-

serve trends in the recent evolution of these pol-

icies.

The indicators are grouped into six areas: inter-

national instruments, which covers each coun-

try’s involvement in treaties and other multilateral

agreements; regional instruments, which analyzes

whether countries are party to agreements cover-

ing the Americas or its subregions; visa-free entry

rights, which measures whether a visa is required

to enter the country; access to temporary resi-

dence, which examines preferences in the granting

of residence permits and regularization processes

for irregular migrants; rights while resident, which

looks at migrants’ access to healthcare, education

services and the labor market, family reunification,

voting rights, and permanent residence; and na-

tionality, which measures whether the nationality

of a given country is only obtained at birth or can

be acquired through a subsequent naturalization

process.

The value assigned to each indicator is backed by

a reference to the legal instruments that define

the policy in question. For most indicators, a text

containing additional information explaining the

specific case is also provided. This is a unique da-

tabase for LAC and is included in Annex II of this

report. It can also be accessed through the IDB Mi-

gration Unit web page.

THE MAIN FINDINGS FROM OUR

ANALYSIS OF THE DATABASE ARE:

A legal regime for migration has begun to

emerge in Latin America in the 21st centu-

ry. This includes the adoption of new migra-

tion laws that are generally accompanied by

subregional mobility schemes, such as the

MERCOSUR, Bolivia, and Chile Residency

Agreement and, more recently, the Andean

Statute. This new 21st-century model tends

to include mechanisms for the permanent

regularization of migrants; the right to ac-

cess the labor market, public health systems,

and public education; and the right to family

reunification. These mechanisms are comple-

mented by greater access to voting rights,

at least for local elections. This model is well

established in Mesoamerica, the Southern

Cone, and the Andean countries, but has not

yet made inroads in the Caribbean.

The regularization of irregular migrants

through permanent mechanisms established

by law and extraordinary regularization pro-

grams is now fairly common in Latin Amer-

ica, but not in the Caribbean. The countries

in the region have carried out more than 90

extraordinary regularization programs since

2000.

Migration Policy Regimes 7

Many of these countries oer preferential

access to permanent residency for migrants

from certain other countries that meet basic

criteria. In some cases, they also oer pref-

erential treatment for naturalization. The

only countries that do not allow residency

almost automatically for nationals of at least

one other country in the region are the Ba-

hamas and Haiti in the Caribbean, and Costa

Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Pan-

ama, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico in

Mesoamerica.

The percentage of ratification of both inter-

national and subregional instruments is very

high in Latin America but much lower in the

Caribbean.

Haitian nationals require visas in more coun-

tries in the region than those of any other

nationality, followed by Venezuelans and

Dominicans.

To develop the database, we analyzed some 435

legal instruments that define migration policy in

26 countries, using the 40 indicators.

Our analysis of this compendium of laws, regu-

lations decrees, administrative orders, and other

instruments shows that:

» The legal instruments that are in force in the

Andean countries in the Southern Cone are be-

tween 8 and 15 years old, on average, as com-

pared to 25 to 30 years old in Mesoamerica and

the Caribbean. This is testimony to the increase

in legislative eorts on migration in these two

subregions in recent years.

» In some areas, such as the regulation of visa

regimes or extraordinary programs for regular-

izing irregular migrants, the legislative activity

in question rests largely on decrees and admin-

istrative orders issued by countries’ executive

branches without the intervention of their par-

liaments. This leads to less stable norms that

entail less legal certainty for all stakeholders,

including migrants, the administration, the ju-

diciary, and others.

This database of indicators and legal instruments

is the IDB Migration Unit’s first attempt at under-

taking a comparative analysis of migration policy

regimes in the countries of Latin America and the

Caribbean. The unit will continue to update it,

with the aim of making it a key source of data for

the region.

Regional freedom of movement and resi-

dency agreements have become extremely

commonplace within LAC’s legislative land-

scape and they influence many aspects of

migration policy, such as access to the labor

market or family reunification.

The country that requires visas for visiting

nationals from more states in the region

than any other is Venezuela (11 states), fol-

lowed by Mexico (9). Venezuela’s policy in

this regard owes to its application of the

principle of reciprocity with states that re-

quire visas for Venezuelan nationals. The fact

that Mexico is a transit country to the United

States for some migrants may explain its re-

quirements in this regard.

Migration Policy Regimes 8

Introduction

Migration, the seeking of refuge, intraregional

freedom of movement, and nationality are high-

ly complex legislative areas that are regulated

through a wide variety of instruments at the do-

mestic, bilateral, regional, and international lev-

els. The ability to objectively measure dierent

aspects of countries’ migration policies allows us

to identify the similarities and dierences between

the legislation in force that governs the movement

of people across the region’s borders, their access

to rights and services while resident in their des-

tination country, and their eventual access to that

country’s nationality, should they desire to acquire

it. The methodology developed in this study and

the compendium of legal instruments provide an

overview of migration policy regimes in countries

in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). Future

updates will monitor these issues and examine any

trends that emerge.

This project has analyzed more than 435 legal

instruments from 26 countries, including consti-

tutions (Esponda 2021), regional legislation, bi-

lateral agreements, laws, regulations, decrees,

administrative orders, and other documents such

as public policies or reports. Where necessary, the

appropriate authorities in a given country were

consulted to clarify doubts. The aim of the project

is not to rank countries, as any eort in that direc-

tion would imply a value judgment on the relative

weighting of many factors that it would be impos-

sible to fully justify. Instead, the project seeks to

provide an objective description of the most im-

portant aspects of the regulation of migration pol-

icy in LAC and make this available to the public.

It is important to note that the database does not

evaluate the practical implementation of the claus-

es of the legislation in question.

1

Although practice

may dier in some respects from the letter of the

law (Acosta 2018; Acosta and Freier 2015), analyz-

ing the latter is fundamental to understanding not

only how migration is regulated but also the de-

cisions that migrants make (Blair, Grossman, and

Weinstein 2022 and 2021).

This report presents a series of 40 indicators on

these issues that have been applied to the 26 bor-

rowing member countries of the Inter-American

Development Bank (IDB)

2

. Each indicator consists

of a specific, objective question as to whether the

country has ratified a given treaty, how many times

it has carried out a regularization, or whether or

not it grants a certain right in its legislation. These

indicators enable us to make concrete, objective

comparisons between countries.

THEY COVER THE FOLLOWING AREAS:

1

This report uses the terms “laws,” “legal instruments,” and “norms” interchangeably.

2

For analytical purposes, the countries are divided into four groups: Southern Cone, Andean countries, the Caribbean,

and Mesoamerica.

1. INTERNATIONAL INSTRUMENTS

(17 indicators)

This indicator analyzes each country’s ratification

of the United Nations’ nine main international hu-

man rights treaties that aect people’s interna-

tional freedom of movement, six other treaties that

regulate human mobility, and the Global Compact

on Refugees and the Global Compact for Safe, Or-

dinary and Regular Migration.

Migration Policy Regimes 9

2. REGIONAL INSTRUMENTS

(8 indicators)

6. ACCESS TO NATIONALITY

(5 indicators)

3. VISA-FREE ENTRY TO COUNTRIES

(1 indicator)

4. ACCESS TO TEMPORARY RESIDENCY

(3 indicators)

5. RIGHTS WHILE RESIDENT

(6 indicators)

This examines the ratification of conventions and

agreements within the Americas on human rights

and refuge, and also considers countries’ involve-

ment in dierent subregional mobility schemes.

The final aspect of our analysis of migration cov-

ers legal standards on access to nationality, which

includes not only the possibility of naturalization

but also access to nationality for the children of

This measures the number of countries whose na-

tionals require a visa to enter any other country

in the region. Entering another country is the first

step on any migration journey.

Once a migrant has entered another country, ob-

taining a residency permit is the next key step in

their migration journey. This indicator includes

subindicators for preferential access to residency

for nationals of countries in the same subregion

and two indicators that examine the regularization

mechanisms available to irregular migrants.

While a migrant is resident in the country, their in-

tegration into the host society may be facilitated

by their having the right to access the labor mar-

ket and public healthcare and education services,

to take part in political life by voting, to family re-

unification, and to eventually obtain permanent

residency.

migrants that are born in the country in question

(jus soli). To complement this, we also examined

the regulations for obtaining nationality for the

children of nationals born abroad (jus sanguinis).

Finally, we analyzed whether each country allows

dual citizenship for nationals who acquire another

nationality and for foreigners who become local

citizens.

The universe of countries covered is the 26 bor-

rowing member countries of the IDB, such that

the database contains 1,040 indicators. There are

three types of indicators. The majority (32) are

binary and therefore measure whether an inter-

national instrument has been ratified or not, or

whether a right is granted or not. Two of the indi-

cators are numeric and reveal the number of bor-

rowing countries whose nationals require a visa to

enter the country in question, or the number of ex-

traordinary regularizations that have been carried

out since 2000. Finally, six indicators have three

possible answers: “not permitted,” “permitted for

some migrants,” or “permitted for all migrants,”

with variations in the three categories as needed

for the indicator in question.

As tends to be the case when gathering policy in-

dicators, it is often dicult to provide a precise

response as to whether or not a certain treatment

is granted, given that a country may do so for a

certain group of migrants or only under certain

circumstances. Consequently, for each indicator,

the database includes additional information that

qualifies or clarifies the assigned value, as well as a

reference to the law or laws on which the analysis

and assigned value are based, including the specif-

ic article. Finally, a link to each law is also included

to facilitate the use of the database.

THE PURPOSE OF THIS DOCUMENT IS TO

PRESENT THE PROJECT’S MAIN FINDINGS.

The next section examines the six areas into which

it is divided: international instruments, regional in-

struments, visa-free entry, temporary residency,

rights while resident, and, finally, nationality. Each

section presents the results descriptively, after

which we examine the main trends in more detail.

After analyzing the indicators, we briefly review

the body of legal instruments that were compiled

and examined for the project, which is followed

by some concluding comments. The methodology

and a glossary of terms are included in annexes to

the report.

Migration Policy Regimes 10

1. International Instruments

This section is divided into three sections that

analyze various international instruments that af-

fect the regulation of human mobility. It begins by

looking at the ratification of the nine main UN in-

ternational human rights treaties (which are sum-

marized in table 1). The second section covers the

ratification of five conventions and an additional

protocol that all influence the legal regime for hu-

man mobility in various ways. The third section ex-

amines two instruments that are not international

treaties but that are highly significant (table 2).

The reason that they are not international treaties

is because the international community decided

to produce two declarations that are far-reaching

but not legally binding. They cannot be ratified but

merely supported or endorsed.

1.a.1 International Convention on the Elimination

of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD)

3

,

December 21, 1965

This convention seeks to eradicate racial discrim-

ination and hatred. It also guarantees the enjoy-

ment of certain civil, political, economic, social,

and cultural rights without discrimination on the

grounds of race, color, descent, or national or eth-

nic origin. These rights include the right to free-

dom of movement and residency within the ter-

ritory of a state; the right to leave any country,

including one’s own, and to return to one’s coun-

try; and the right to a nationality (article 5). Some

182 countries have ratified the CERD, including all

IDB borrowing member states.

1.a Main international United Nations

human rights treaties

3

Abbreviations used in this document are those used by the UN.

1.a.2 International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights (ICCPR), December 16, 1966

This convention seeks to guarantee the protection

of the civil and political rights of those who are in

the territory of a state and subject to its jurisdic-

tion, without any discrimination. This includes spe-

cific rights for foreigners in relation to the guaran-

tees and procedures that must be complied with

in the case of expulsion from the country (article

13). Some 173 countries have ratified the ICCPR,

including all IDB borrowing member countries.

1.a.3 International Covenant on Economic, Social,

and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), December 16, 1966

The ICESCR seeks to guarantee a series of rights

in areas such as education, health, social securi-

ty, and labor. All IDB borrowing member countries

are part of the group of 171 countries that have rat-

ified the covenant.

1.a.4 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms

of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), De-

cember 18, 1979

The objective of CEDAW is to eliminate all forms

of discrimination against women, which is under-

stood as any “distinction, exclusion, or restriction

made on the basis of sex which has the eect or

purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition,

enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of

their marital status, on a basis of equality of men

and women, of human rights...” (article 1). Article

9 is particularly relevant since it establishes equal

rights for women to “acquire, change or retain

their nationality”; that neither marriage to an alien

nor change of nationality by the husband during

Migration Policy Regimes 11

marriage shall automatically change the national-

ity of the wife, render her stateless or force upon

her the nationality of the husband”; and that states

parties grant “women equal rights with men with

respect to the nationality of their children.” CE-

DAW has been ratified by 189 countries, including

all IDB borrowing member states.

1.a.5 Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel,

Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

(CAT), December 10, 1984

The section of this convention that is most rele-

vant to this study is article 3: “No State Party shall

expel, return (“refouler”) or extradite a person to

another State where there are substantial grounds

for believing that he would be in danger of being

subjected to torture.” The CAT has been ratified by

171 countries, 21 of which are IDB borrowing mem-

ber states.

1.a.6 Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC),

November 20, 1989

The purpose of this convention is to protect the

rights of children under the age of 18. The main

clauses are contained in articles 7 (the right to ac-

quire a nationality after birth) and 9–10 (on family

unity and reunification). The CRC has been ratified

by all IDB borrowing member states and 196 coun-

tries globally.

1.a.7 International Convention on the Protection

of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members

of Their Families (ICMW), December 18, 1990

This is the most important international trea-

ty on the rights of migrants and their families.

It includes rights that apply to all migrants, regard-

less of whether their status is irregular (articles

8–35), and rights that only apply to migrant work-

ers who are documented or whose status is reg-

ular (articles 36–56). The ICMW has been ratified

by 17 borrowing member states and 57 countries

in total.

1.a.8 Convention on the Rights of Persons with

Disabilities (CRPD), December 13, 2006

This treaty seeks to guarantee “full and equal en-

joyment of all human rights and fundamental free-

doms by all persons with disabilities” (article 1).

The most important article in relation to this study

is article 18, which establishes freedom of move-

ment and nationality, including the right to acquire

and change nationality, leave any country includ-

ing one’s own, enter one’s own country, or acquire

a nationality after birth. The CRPD has been rat-

ified by all IDB borrowing member states and by

184 countries in total.

1.a.9 International Convention for the Protec-

tion of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance

(CPED), December 20, 2006

This convention prohibits the use of forced disap-

pearance against any person. The most relevant

section of the CPED is article 16: “No State Par-

ty shall expel, return (“refouler”), surrender or ex-

tradite a person to another State where there are

substantial grounds for believing that he or she

would be in danger of being subjected to enforced

disappearance.” This CPED has been ratified by 13

IDB borrowing member states out of a total of 63.

Migration Policy Regimes 12

TABLE 1: International Instruments (date of ratification)

CARIBBEAN

BAHAMAS

1.a.1 ICERD

8 / 5 / 1975 11 / 8 / 1972 11 / 14 / 2001 2 / 15 / 1977 12 / 19 / 1972 6 / 4 / 1971 3 / 15 / 1984 10 / 4 / 1973

BARBADOS BELIZE GUYANA HAITI JAMAICA SURINAME TRINIDAD & TOBAGO

1.a.2 ICCPR

12 / 23 / 2008 1 / 5 / 1973 6 / 10 / 1996 2 / 15 / 1977 2 / 6 / 1991 10 / 3 / 1975 12 / 28 / 1976 12 / 21 / 1978

1.a.3 ICESCR

12 / 23 / 2008 1 / 5 / 1973 3 / 9 / 2015 2 / 15 / 1977 10 / 8 / 2013 10 / 3 / 1975 12 / 28 / 1976 12 / 8 / 1978

1.a.4 CEDAW

10 / 6 / 1993 10 / 16 / 1980 6 / 16 / 1990 7 / 17 / 1980 7 / 20 / 1981 10 / 19 / 1984 3 / 1 / 1993 1 / 12 / 1990

1.a.5 CAT

5 / 31 / 2018

Not

Ratified

3 / 17 / 1986 5 / 19 / 1988

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

11 / 16 / 2021

Not

Ratified

1.a.6 CRC

2 / 20 / 1991 10 / 9 / 1990 5 / 2 / 1990 1 / 14 / 1991 6 / 8 / 1995 5 / 14 / 1991 3 / 1 / 1993 12 / 5 / 1991

1.a.7 ICMW

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

11 / 14 / 2001 7 / 7 / 2010

Not

Ratified

9 / 25 / 2008

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

1.a.8 CRPD

9 / 28 / 2015 2 / 27 / 2013 6 / 2 / 2011 9 / 10 / 2014 7 / 23 / 2009 3 / 30 / 2007 3 / 29 / 2017 6 / 25 / 2015

1.a.9 CPED

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

8 / 14 / 2015

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

SOTHERN CONE

ARGENTINA

1.a.1 ICERD

2 / 10 / 1968

27 / 3 / 1968 20 / 10 / 1971 18 / 8 / 2003 30 / 8 / 1968

BRAZIL CHILE PARAGUAY URUGUAY

1.a.2 ICCPR

8 / 8 / 1986 24 / 1 / 1992 10 / 2 / 1972 10 / 6 / 1992 1 / 4 / 1970

1.a.3 ICESCR

8 / 8 / 1986 24 / 1 / 1992 10 / 2 / 1972 10 / 6 / 1992 1 / 4 / 1970

1.a.4 CEDAW

15 / 7 / 1985 1 / 2 / 1984 7 / 12 / 1989 6 / 4 / 1987 9 / 10 / 1981

1.a.5 CAT

24 / 9 / 1986 28 / 9 / 1989 30 / 12 / 1988 12 / 3 / 1990 24 / 10 / 1986

1.a.6 CRC

4 / 12 / 1990 24 / 9 / 1990 13 / 8 / 1990 25 / 9 / 1990 20 / 11 / 1990

1.a.7 ICMW

23 / 2 / 2007 21 / 3 / 2005

Not

Ratified

23 / 9 / 2008 15 / 2 / 2001

1.a.8 CRPD

2 / 9 / 2008 1 / 8 / 2008 29 / 7 / 2008 3 / 9 / 2008 11 / 2 / 2009

1.a.9 CPED

14 / 12 / 2007 29 / 11 / 2010 8 / 12 / 2009 3 / 8 / 2010 4 / 3 / 2009

MESOAMERICA + MEXICO

COSTA RICA

1.a.1 ICERD

1 / 16 / 1967 11 / 30 / 1979 1 / 18 / 1983 10 / 10 / 2002 2 / 20 / 1975 2 / 15 / 1978 8 / 16 / 1967 5 / 25 / 1983

EL SALVADOR GUATEMALA HONDURAS MEXICO NICARAGUA

PANAMA

DOMINICAN

REPUBLIC

1.a.2 ICCPR

11 / 29 / 1968 11 / 30 / 1979 5 / 5 / 1992 8 / 25 / 1997 3 / 23 / 1981 3 / 12 / 1980 3 / 8 / 1977 1 / 4 / 1978

1.a.3 ICESCR

11 / 29 / 1968 11 / 30 / 1979 5 / 19 / 1988 2 / 17 / 1981 3 / 23 / 1981 3 / 12 / 1980 3 / 8 / 1977 1 / 4 / 1978

1.a.4 CEDAW

4 / 4 / 1986 8 / 19 / 1981

6 / 17 / 1996

8 / 12 / 1982 3 / 3 / 1983 3 / 23 / 1981

1 / 23 / 1986

10 / 27 / 1981

7 / 5 / 2005

10 / 29 / 1981 9 / 2 / 1982

1.a.5 CAT

11 / 11 / 1993 1 / 5 / 1990 12 / 5 / 1996 8 / 24 / 1987

1.a.6 CRC

8 / 21 / 1990 7 / 10 / 1990 6 / 6 / 1990 8 / 10 / 1990 9 / 21 / 1990

3 / 8 / 1999

10 / 5 / 1990 12 / 12 / 1990 6 / 11 / 1991

1 / 24 / 2012

1.a.7 ICMW

Not

Ratified

3 / 14 / 2003 3 / 14 / 2003 8 / 9 / 2015 10 / 26 / 2005

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

1.a.8 CRPD

10 / 1 / 2008 12 / 14 / 2007 4 / 7 / 2009 4 / 14 / 2008 12 / 17 / 2007

3 / 18 / 2008

12 / 7 / 2007 8 / 7 / 2007

6 / 22 / 2011

8 / 18 / 2009

1.a.9 CPED

2 / 16 / 2012 4 / 1 / 2008

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Migration Policy Regimes 13

TABLE 1: International Instruments (date of ratification) (cont.)

Source: Compiled by the authors.

ANDEAN

BOLIVIA

1.a.1 ICERD

9 / 22 / 1970

9 / 2 / 1981 9 / 22 / 1966 9 / 29 / 1971 10 / 10 / 1967

COLOMBIA ECUADOR PERU VENEZUELA

1.a.2 ICCPR

8 / 12 / 1982 10 / 29 / 1969 3 / 6 / 1969 4 / 28 / 1978 5 / 10 / 1978

1.a.3 ICESCR

8 / 12 / 1982 10 / 29 / 1969 3 / 6 / 1969 4 / 28 / 1978 5 / 10 / 1978

1.a.4 CEDAW

6 / 8 / 1990 1 / 19 / 1982 11 / 9 / 1981 9 / 13 / 1982 5 / 2 / 1983

1.a.5 CAT

4 / 12 / 1999 12 / 8 / 1987 3 / 30 / 1988 7 / 7 / 1988 7 / 29 / 1991

1.a.6 CRC

6 / 26 / 1990 1 / 28 / 1991

5 / 24 / 1995

3 / 23 / 1990 9 / 4 / 1990 9 / 13 / 1990

1.a.7 ICMW

10 / 16 / 2000 2 / 52 / 2002

Not

Ratified

9 / 14 / 2005 10 / 25 / 2016

1.a.8 CRPD

11 / 16 / 2009 5 / 10 / 2011 4 / 3 / 2008 1 / 30 / 2008 9 / 24 / 2013

1.a.9 CPED

12 / 17 / 2008 7 / 11 / 2012 10 / 20 / 2009 9 / 26 / 2012

1.b.1 Convention Relating to the Status of Refu-

gees (CSR), July 28, 1951

The CSR defines the term “refugee” and establish-

es the legal status and protection owed to those

who are granted this status. It applies to people

who are refugees as a result of events that took

place before January 1, 1951.

1.b.2 Additional Protocol Relating to the Status of

Refugees (APSR), January 31, 1967

The ASPR expands the scope of application of the

CSR by removing the geographical or time limits

that were part of the latter. There are 145 states

parties to the CSR and 146 to the ASPR. All IDB

borrowing member states are parties except Bar-

bados and Guyana, which have not ratified either

instrument, and Venezuela, which has ratified the

ASPR but not the CSR.

1.b.3 Convention Relating to the Status of State-

less Persons (CSP), September 28, 1954

1.b International treaties that aect the

regulation of human mobility

This convention defines the term “stateless per-

son” as someone “who is not considered as a na-

tional by any State” and establishes the legal sta-

tus and protection of such people. The CSP has

been ratified by 96 countries, 20 of which are IDB

borrowing member states.

1.b.4 Convention on the Reduction of Stateless-

ness (CRS), August 30, 1961

The CRS establishes several obligations to reduce

statelessness, including granting nationality to a

person born in the territory who would otherwise

be stateless (article 1) or limiting the state’s ability

to deprive a person of their nationality if doing so

would lead to their being stateless (article 8). It

has been ratified by 77 countries, 17 of which are

IDB borrowing member states.

1.b.5 Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants

by Land, Sea and Air

4

November 15, 2000

The protocol seeks to “prevent and combat the

smuggling of migrants, as well as to promote co-

operation among states parties to that end, while

protecting the rights of smuggled migrants” (arti-

cle 2). The protocol has 178 states parties, includ-

ing all IDB borrowing member states except Boliv-

ia and Colombia.

4

“Smuggling” is the facilitation or promotion of the illegal entry of a person into a country they are not a national or a permanent

resident of, for the purpose of financial gain. See the Glossary (Annex I) for more details.

Migration Policy Regimes 14

5

Tracking is the recruitment or receipt of persons using forms of coercion or fraud for the purpose of exploitation. This includes

sexual exploitation and forced labor. See the Glossary (Annex I) for more details.

1.c Instruments that are not international

treaties

1.c.1 Global Compact on Refugees, December 17,

2018

The Global Compact on Refugees is an agreement

negotiated at the government level that establish-

es four key objectives: alleviate pressures on host

countries, enhance refugee self-reliance, expand

1.b.6 Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish

Tracking

5

in Persons, Especially Women and

Children, December 12, 2000

The purpose of the protocol is to “prevent and

combat tracking in persons,” especially women

and children, and to “protect and assist the vic-

tims of such tracking” (article 2). The protocol

has 150 states parties, including all IDB borrowing

member states.

TABLE 2: International Instruments

CARIBBEAN

BAHAMAS

1.b.1 CSR 1951

15 / 9 / 1993 27 / 6 / 1990

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

25 / 9 / 1984 30 / 7 / 1964 29 / 11 / 1978 10 / 11 / 2000

BARBADOS BELIZE GUYANA HAITI JAMAICA SURINAME TRINIDAD & TOBAGO

1.b.2 APSR

1967

15 / 9 / 1993 27 / 6 / 1990 25 / 9 / 1984 30 / 10 / 1980 29 / 11 / 1978 10 / 11 / 2000

1.b.3 CSP

1954

6 / 3 / 1972 14 / 9 / 2006 27 / 9 / 2018 11 / 4 / 1966

1.b.4 CRS

1961

14 / 8 / 2015 27 / 9 / 2018 9 / 1 / 2013

1.b.5

Smuggling

Protocol

2000

26 / 9 / 2008

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

14 / 9 / 2006 16 / 4 / 2008 19 / 4 / 2011 29 / 9 / 2003 25 / 5 / 2007 6 / 11 / 2007

1.b.6

Tracking

Protocol

2000

26 / 9 / 2008

Endorsed Endorsed

11 / 11 / 2014

11 / 11 / 2014

26 / 9 / 2003 14 / 9 / 2004 19 / 4 / 2011 29 / 9 / 2003 25 / 5 / 2007 6 / 11 / 2007

1.c.1 GCM

2018

Not

Endorsed

Endorsed Endorsed

Not

Endorsed

1.c.2 GCR

2018

Endorsed Endorsed Endorsed Endorsed

Endorsed

Endorsed Endorsed

Endorsed

Endorsed Endorsed

access to third-country solutions, and support

conditions in countries of origin for return in safety

and dignity. All but five UN member states voted

in favor; the Dominican Republic was one of the

five abstentions. All other IDB borrowing member

countries supported the Global Compact.

1.c.2 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regu-

lar Migration, December 19, 2018

This is an agreement negotiated at the government

level under the auspices of the United Nations. It

covers all aspects of international migration and

sets out 23 objectives in various areas. Support-

ing states are committed to these objectives. The

Global Compact was adopted by 152 of the 193 UN

member states, including 20 IDB borrowing mem-

ber countries. Brazil initially voted in favor but has

since announced its intention not to endorse the

Global Compact. The other LAC countries that

abstained or voted against it are Belize, Chile, the

Dominican Republic, Paraguay, and Trinidad and

Tobago.

Migration Policy Regimes 15

TABLE 2: International Instruments (cont.)

SOUTHERN CONE

1.b.1 CSR 1951

1.b.2 APSR

1967

1.b.3 CSP

1954

1.b.4 CRS

1961

1.b.5

Smuggling

Protocol

2000

1.b.6

Tracking

Protocol

2000

1.c.1 GCM

2018

1.c.2 GCR

2018

ARGENTINA

15 / 11 / 1961

6 / 12 / 1967

1 / 6 / 1972

13 / 11 / 2014

19 / 11 / 2002

19 / 11 / 2002

Endorsed

Endorsed

16 / 11 / 1960

BRAZIL

7 / 4 / 1972

13 / 8 / 1996

25 / 10 / 2007

29 / 1 / 2004

29 / 1 / 2004

Not

Endorsed

Endorsed

28 / 1 / 1972

CHILE

27 / 4 / 1972

11 / 4 / 2018

11 / 4 / 2018

29 / 11 / 2004

29 / 11 / 2004

Not

Endorsed

Endorsed

1 / 4 / 1970

PARAGUAY

1 / 4 / 1970

1 / 7 / 2014

6 / 6 / 2012

23 / 9 / 2008

22 / 9 / 2004

Not

Endorsed

Endorsed

22 / 9 / 1970

URUGUAY

22 / 9 / 1970

2 / 4 / 2004

21 / 9 / 2012

4 / 3 / 2005

4 / 3 / 2005

Endorsed

Endorsed

1.b.1 CSR 1951

28 / 3 / 1978 22 / 9 / 1983

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

7 / 6 / 2000 28 / 3 / 1980 2 / 8 / 1978 4 / 1 / 1978

1.b.2 APSR

1967

28 / 3 / 1978

28 / 4 / 1983

28 / 4 / 1983 22 / 9 / 1983 7 / 6 / 2000 28 / 3 / 1980 2 / 8 / 1978 4 / 1 / 1978

1.b.3 CSP

1954

9 / 2 / 20152 / 11 / 1977 28 / 11 / 2000 7 / 6 / 2000 15 / 7 / 2013

1.b.4 CRS

1961

19 / 7 / 2001

23 / 3 / 1992

23 / 3 / 1992

1 / 10 / 2012

18 / 12 / 20122 / 11 / 1977 29 / 7 / 2013

2 / 6 / 2011

2 / 6 / 2011

1.b.5

Smuggling

Protocol

2000

7 / 8 / 2003

Not

Ratified

1 / 4 / 2004 18 / 12 / 2008 4 / 3 / 2003 15 / 2 / 2006 18 / 8 / 2004 10 / 12 / 2007

1.b.6

Tracking

Protocol

2000

9 / 9 / 2003

Endorsed Endorsed Endorsed

18 / 3 / 2004

18 / 3 / 2004

1 / 4 / 2004 1 / 4 / 2008 4 / 3 / 2003 12 / 10 / 2004 18 / 8 / 2004 5 / 2 / 2008

1.c.1 GCM

2018

Endorsed Endorsed

Not

Endorsed

Not

Endorsed

1.c.2 GCR

2018

Endorsed Endorsed Endorsed Endorsed

Endorsed

Endorsed Endorsed

Endorsed

Endorsed

MESOAMERICA + MEXICO

COSTA RICA EL SALVADOR GUATEMALA HONDURAS MEXICO NICARAGUA

PANAMA

DOMINICAN

REPUBLIC

Migration Policy Regimes 16

TABLE 2: International Instruments (cont.)

Source: Compiled by the authors.

ANDINOS

1.b.1 CSR 1951

1.b.2 APSR

1967

1.b.3 CSP

1954

1.b.4 CRS

1961

1.b.5

Smuggling

Protocol

2000

1.b.6

Tracking

Protocol

2000

1.c.1 GCM

2018

1.c.2 GCR

2018

17 / 8 / 1955

ECUADOR

6 / 3 / 1969

2 / 10 / 1970

24 / 9 / 2012

17 / 9 / 2012

Endorsed

17 / 9 / 2012

Endorsed

21 / 12 / 1964

PERÚ

15 / 9 / 1983

23 / 1 / 2014

18 / 12 / 2014

23 / 1 / 2002

Endorsed

23 / 1 / 2002

Endorsed

BOLIVIA

9 / 2 / 1982

9 / 2 / 1982

6 / 10 / 1983

6 / 10 / 1983

18 / 5 / 2006

Endorsed

Endorsed

Not

Ratified

10 / 10 / 1961

COLOMBIA

4 / 3 / 1980

7 / 10 / 2019

15 / 8 / 2014

Endorsed

4 / 8 / 2004

Endorsed

Not

Ratified

VENEZUELA

19 / 9 / 1986

15 / 4 / 2005

13 / 5 / 2002

Endorsed

Endorsed

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

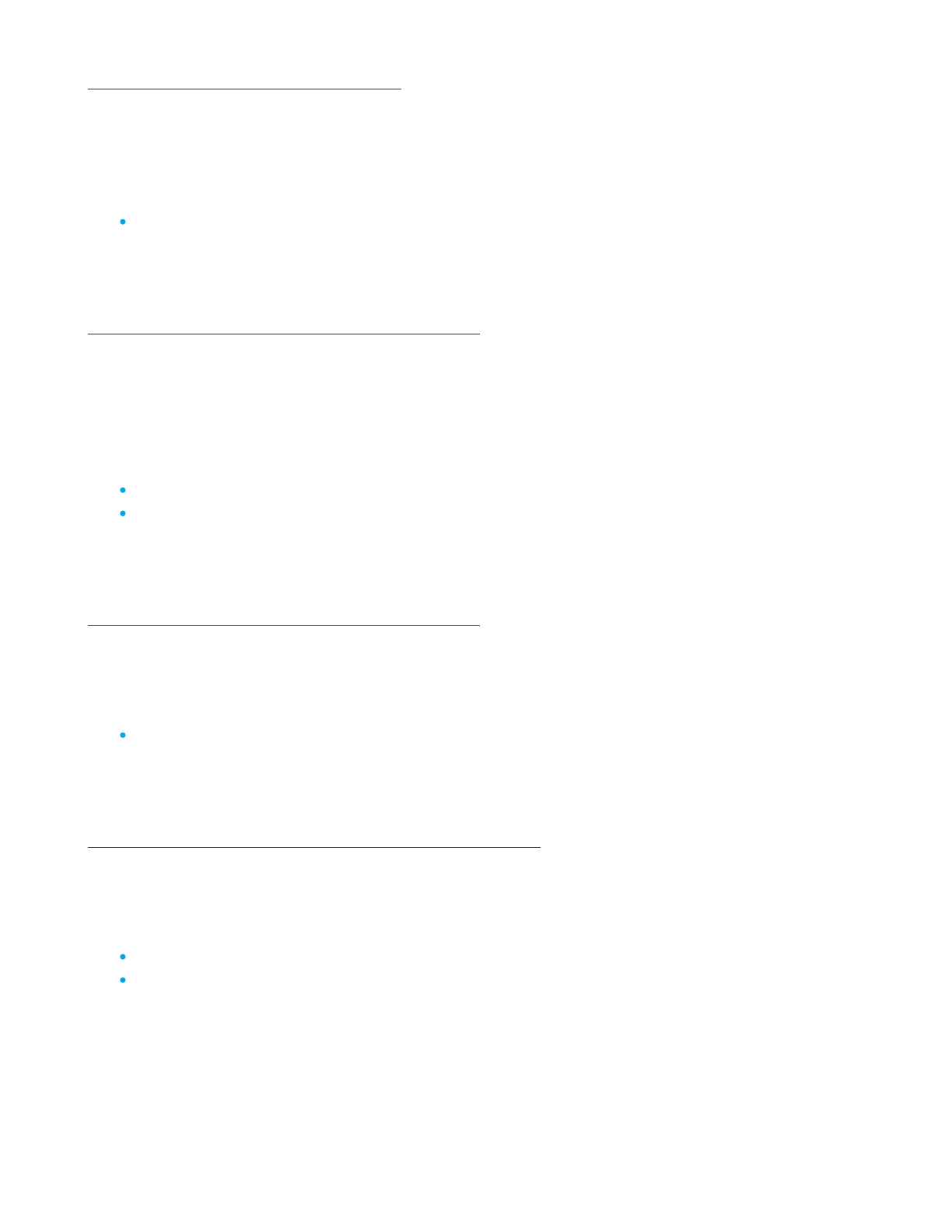

Findings relating

to international instruments

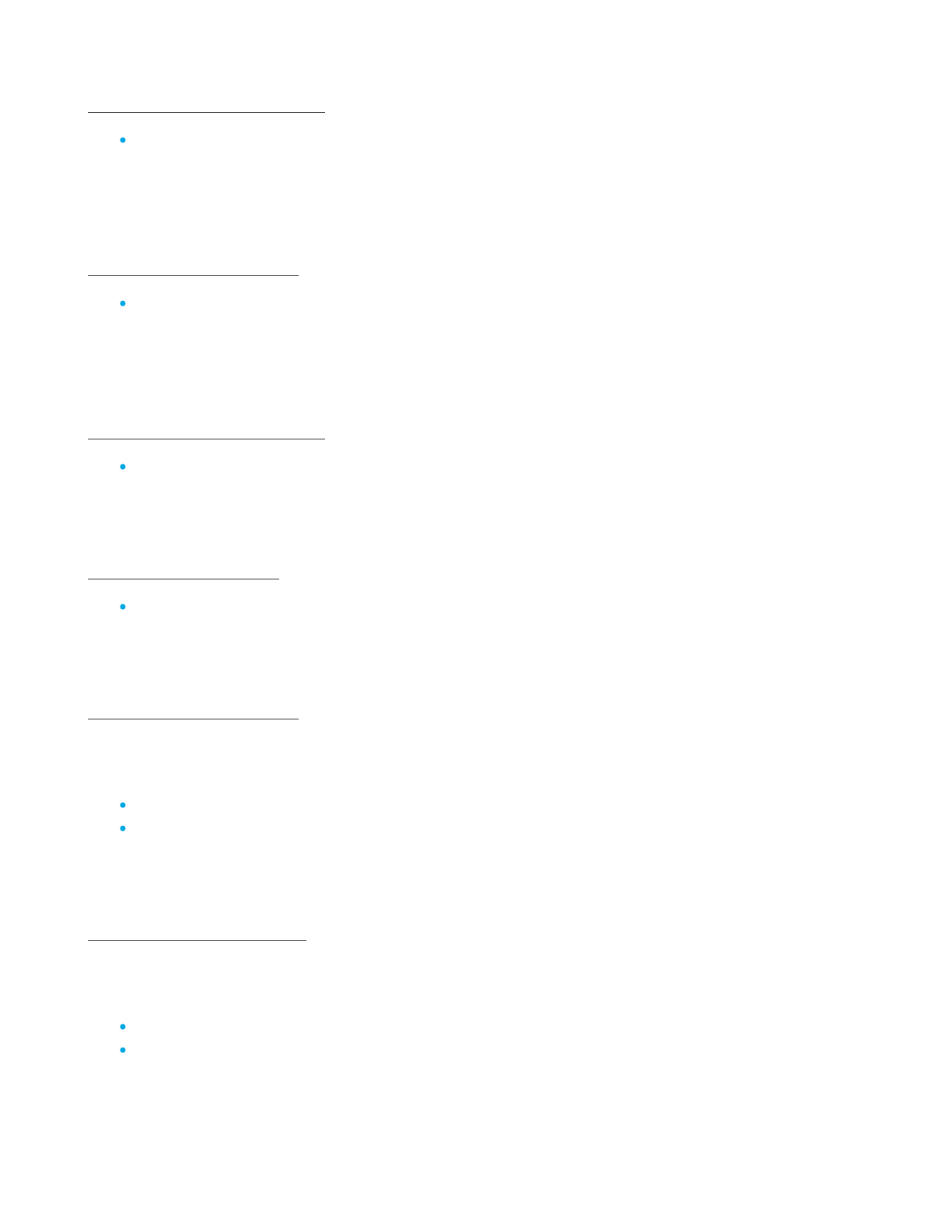

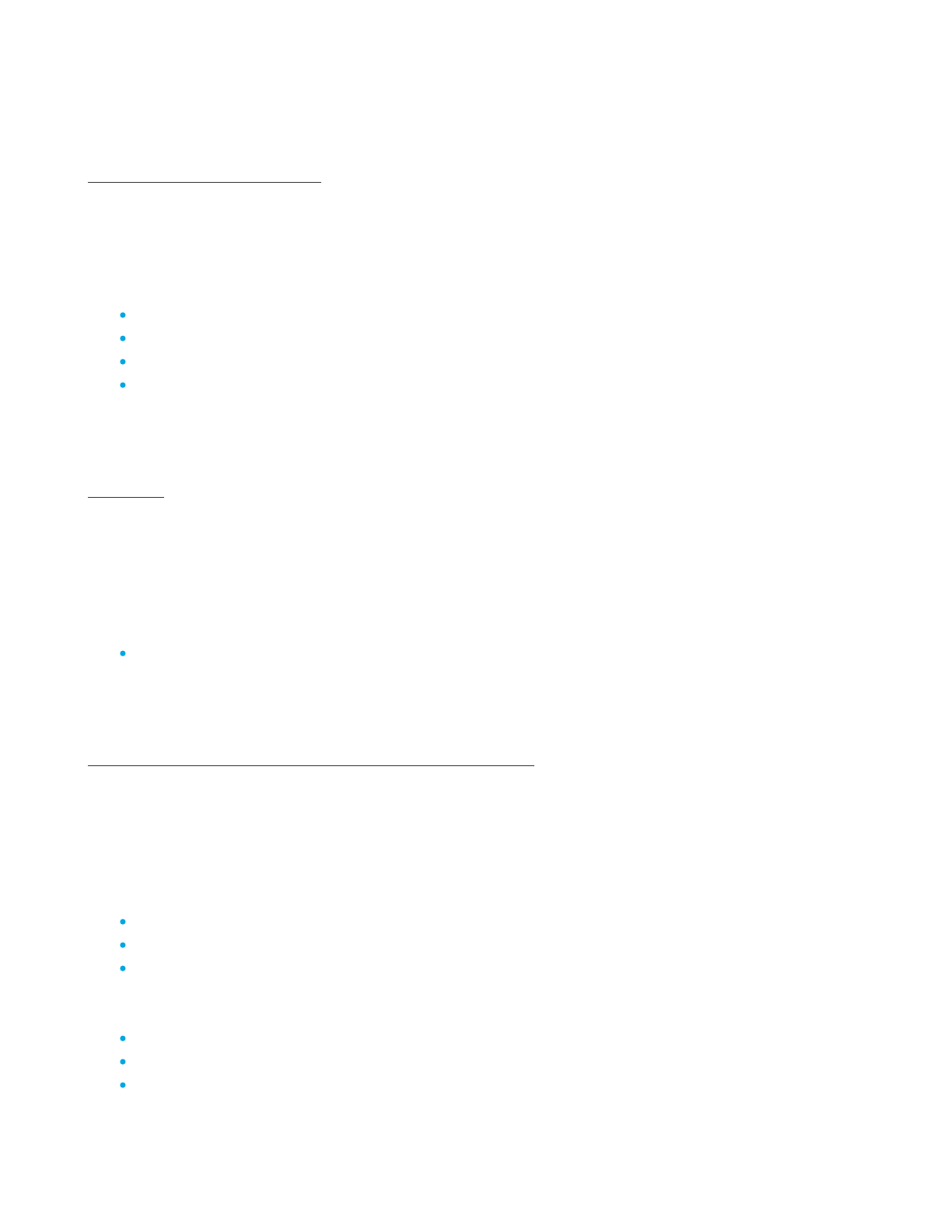

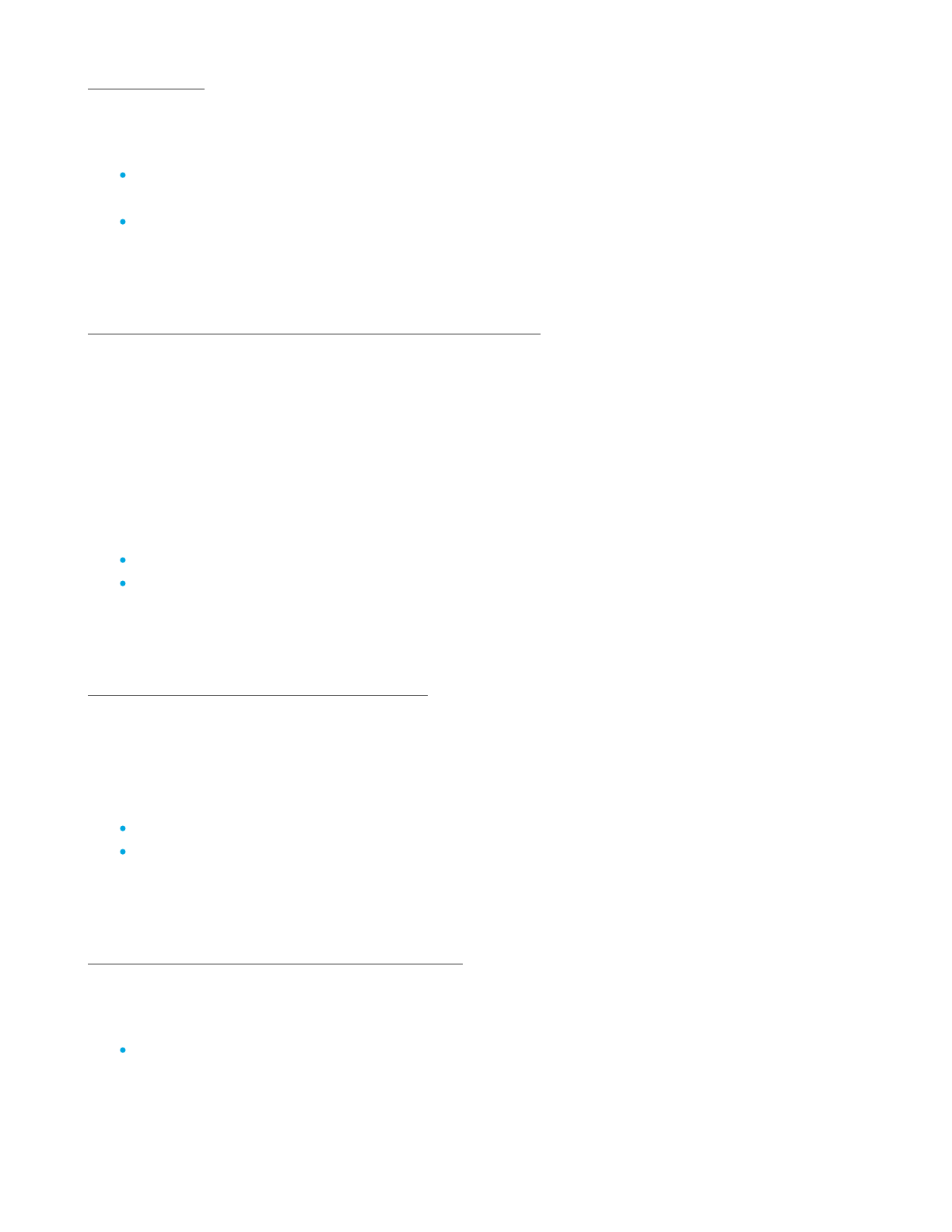

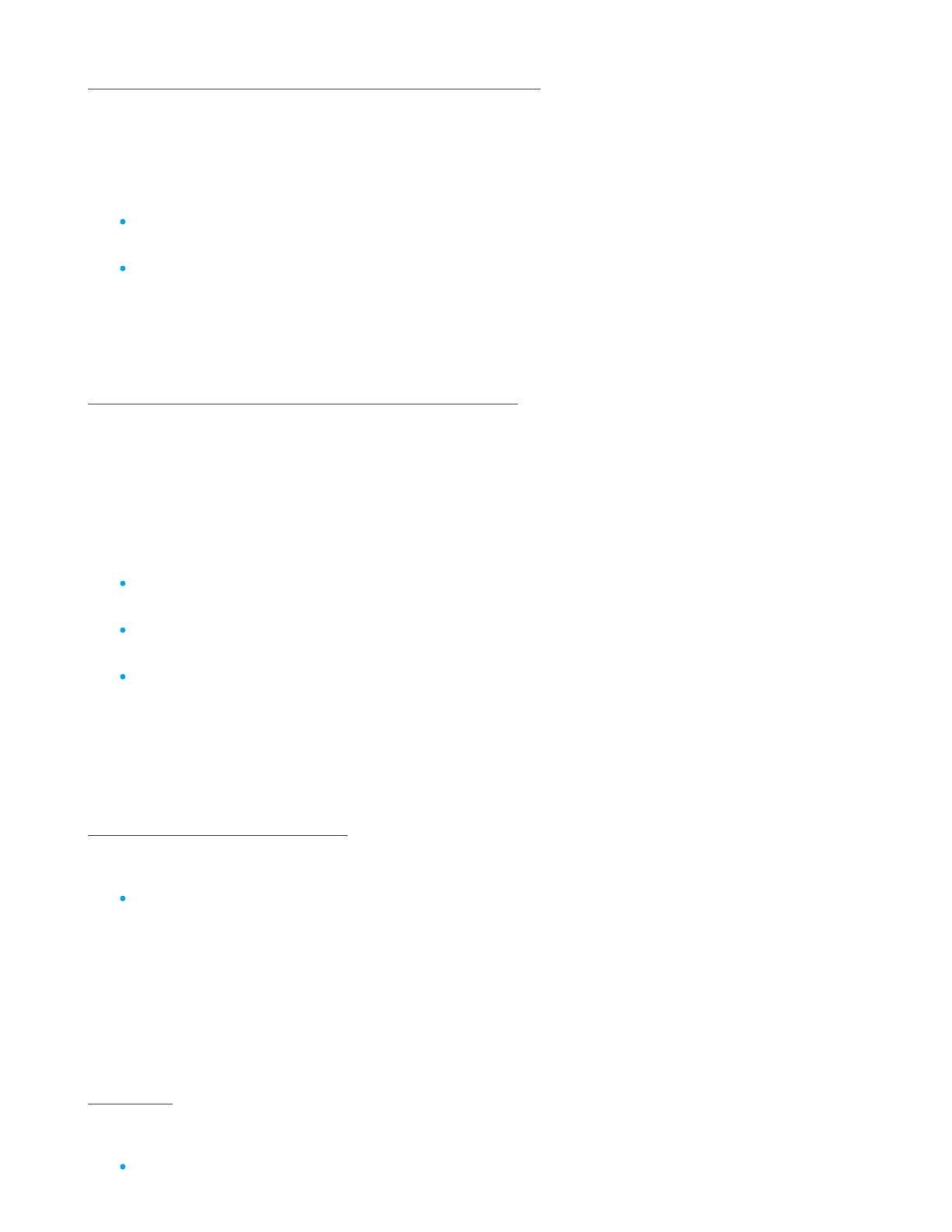

The main finding is that the rate of ratification of

these instruments is very high for IDB borrowing

member states in general, but is much lower in

the Caribbean. First, of the total 234 possible rat-

ifications of the nine main UN human rights trea-

ties by the 26 countries, 209 have been carried

out. Some 16 of these 25 nonratifications are from

Caribbean countries and 7 are from countries in

Mesoamerica. Of the 156 possible ratifications of

the 6 international treaties that aect the regula-

tion of human mobility, 22 (or 14%) have not taken

place. Of these 22, 13 are from the Caribbean, and

7 are from Mesoamerica (see figure 1). The two

2018 Global Compacts provided 52 opportunities

for support from the 26 IDB borrowing member

countries. Of these, 7 (13%) did not take place. The

Andean countries are the only subregion to have

fully supported both global compacts (figure 2).

Five countries (Argentina, Ecuador, Honduras,

Peru, and Uruguay) have ratified or endorsed

all the treaties. At the other extreme are the

Dominican Republic and Barbados, which have

rejected the most instruments (six), followed by

Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago which have not

ratified or supported five of them. The relative fre-

quency of nonratifications by Caribbean countries

may be explained by these not being independent

countries at the time that the treaties were negoti-

ated, although this does not explain why they have

not joined subsequently.

Of the 16 instruments analyzed (taking the CSR

and the ASPR as a single instrument), 7 have been

ratified by all states and 9 have been rejected

by at least one IDB borrowing member country.

Leaving aside the Convention for the Protection

of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, the

relevance of which to the regulation of mobility

is more limited, the Convention on the Reduction

of Statelessness and International Convention on

the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Work-

ers and Members of Their Families are the least

accepted of the 16 instruments, as nine countries

have still not joined them, most of which are in

the Caribbean. Positive progress has been made

on the Convention on the Reduction of Stateless-

ness, which has been ratified by 12 states since

2010, some of which (e.g., Argentina, Paraguay,

Migration Policy Regimes 17

FIGURE 1: Ratification of the 16 Human Rights and Human Mobility Treaties

FIGURE 2: Support for the Global Compacts for Refugees and Safe and Regular Migration

Not ratified Ratified

Total Caribbean Andean

Countries

100%

80%

60%

40%

20%

0%

Southern

Cone

Mesoamerica

Not endorsed Endorsed

Total Caribbean Andean

Countries

100%

80%

60%

40%

20%

0%

Southern

Cone

Mesoamerica

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Source: Compiled by the authors.

and Uruguay) have also recently enacted specific

domestic laws in this area. The International Con-

vention on the Protection of the Rights of All Mi-

grant Workers and Members of Their Families may

be ratified by other states in the near future. For

example, Haiti signed it in 2013 but has not yet rat-

ified it, while Brazil’s Congress has been debating

doing so since 2010.

6

In fact, of the 57 states that

have ratified it worldwide, 17 (30%) are IDB bor-

rowing member countries, so the overall trend in

LAC is to be a party to this instrument.

Two other factors are worth noting. Most of the

states included in this study adopted specific laws

on human tracking, although issues relating to

migrant smuggling tend to be included in migra-

tion laws. Three exceptions to this are Ecuador,

which regulates human tracking in its human

mobility law, Suriname, and Venezuela. Further-

more, while all LAC countries except Barbados

and Guyana have ratified the Refugee Convention

and/or the Additional Protocol to this, there are

five that have not passed any national laws in this

area (Bahamas, Haiti, Jamaica, Trinidad and Toba-

go, and Suriname). This is a major challenge that

could pose huge diculties when it comes to rec-

ognizing refugee status and providing protection

for those holding this.

6

For more information steps have been taken as part of this process, see the following link (last accessed December 29, 2021):

https://www.camara.leg.br/proposicoesWeb/fichadetramitacao?idProposicao=489652

Migration Policy Regimes 18

2. Regional Instruments

This section is divided into three subsections

that analyze the dierent regional instruments

that aect the regulation of human mobility. The

first of these examines the ratification of two in-

ter-American conventions. The second covers two

indicators that do not refer to the ratification of a

specific duty but rather to the recognition of the

jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court of Human

Rights and the domestic implementation of the

Cartagena Declaration on Refugees. The third ex-

plores the ratification of subregional instruments

that facilitate the free movement of persons (see

Table 3). Finally, it is worth noting the importance

of some regional forums in which migration topics

have been discussed in recent years, such as the

South American Conference on Migration or the

Quito Process. These are not included here as they

do not produce binding legal norms.

2.a.1 American Convention on Human Rights

(ACHR), November 22, 1969

Also known as the Pact of San José, this is the most

important human rights instrument in the Ameri-

cas and includes an extensive list of civil and po-

litical rights. It also establishes the two competent

bodies that are empowered to ensure compliance

with the ACHR: the Inter-American Commission

on Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of

Human Rights. The ACHR has been ratified by 24

states in the Americas, including all the IDB bor-

rowing member countries except the Bahamas,

Belize, Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago.

2.b.1 Jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court of

Human Rights (IA Court)

This indicator refers to the countries that have

recognized the jurisdiction of the IA Court as per

article 62 of the ACHR. Some 20 IDB borrowing

member countries have done so to date; the only

countries that have not are the following Carib-

bean countries: Bahamas, Belize, Guyana, Jamai-

ca, and Trinidad and Tobago, the latter of which

has also not ratified the ACHR. The Dominican

Republic is currently in legal limbo on this matter.

Through ruling 256 of 2014, the Dominican Con-

stitutional Court declared that the jurisdiction of

the IA Court had not been recognized through

the proper procedure and that it therefore did not

have jurisdiction. Conversely, in March 12, 2019, the

IA Court issued an order in which it deemed that

the Constitutional Court ruling of November 4,

2014, has no legal eect under international law.

2.a Regional conventions

2.b Other indicators

for regional cooperation

2.a.2 Additional Protocol to the American Conven-

tion on Human Rights in the Area of Economic,

Social and Cultural Rights, November 17, 1988

Also known as the Protocol of San Salvador, this

instrument includes a number of fundamental

socioeconomic rights, such as the right to edu-

cation, social security, and health or labor rights.

It has been ratified by 17 IDB borrowing member

countries, most of which are in Central and South

America. Most Caribbean countries have not yet

ratified it, including the Bahamas, Barbados, Be-

lize, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, and Trinidad and To-

bago, and neither has the Dominican Republic.

Chile is likely to be the next state to ratify it, as its

Senate approved this in July 2021.

Migration Policy Regimes 19

2.b.2 Cartagena Declaration on Refugees,

November 22, 1984

The Cartagena Declaration is a non-legally bind-

ing instrument that was adopted in 1984, a time

when a large number of Central American citizens

were fleeing their countries but whose legal status

did not fall under the definition of refugee in the

1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of

Refugees, or the 1967 Additional Protocol to this.

The Cartagena Declaration expanded the concept

of refugee to include “persons who have fled their

country because their lives, safety or freedom have

been threatened by generalized violence, foreign

aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of

human rights or other circumstances which have

seriously disturbed public order.”.

7

This expand-

ed definition has been included in part or in full

in the domestic legislation of 15 IDB borrowing

member states: Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil,

Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala,

Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, and

Uruguay. In Costa Rica, the Cartagena Declaration

has been applied at the judicial level. The remain-

ing IDB borrowing member countries have not in-

cluded the expanded definition in their domestic

legislation.

2.c.1 Residency Agreement for Nationals of the

MERCOSUR States Parties, Bolivia, and Chile, De-

cember 6, 2002

This agreement entered into force in 2009 and is

open for ratification by any of the full and associ-

ate member countries of MERCOSUR. This means

that all 12 South American countries can join it.

Guyana, Suriname, and Venezuela are the only

2.c Subregional instruments

on the free movement of persons

countries that have not ratified the agreement to

date. It oers nationals of states parties the right

to residency in another state. Specifically, it en-

ables them to obtain a two-year temporary res-

idency permit that can then be converted into a

permanent one. The agreement covers a variety of

rights, including the rights to work, education, or

family reunification.

2.c.2 Decision No. 878 Andean Migration Statute,

May 12, 2021

This decision entered into force on August 11,

2021, and is directly applicable in the four mem-

ber states of the Andean Community: Bolivia, Co-

lombia, Ecuador, and Peru. The statute adds to the

set of instruments that have already been adopted

by the Andean Community and that facilitate the

free movement of people, including Decision 545,

which only applies to workers. It establishes that

nationals of these countries have the right to re-

side in any of the other states, as do any foreigners

with permanent residency rights in any of them.

Those in question are initially granted a temporary

residency permit that may later be converted into

a permanent one. The statute provides access to

rights such as education or family reunification, as

well as the right to work, including self-employ-

ment.

2.c.3 Central American Free Mobility Agreement

CA-4, June 20, 2006

This agreement was signed by the migration au-

thorities of El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and

Nicaragua within the framework of the Central

American Integration System (SICA). The other

four SICA member states (Belize, Costa Rica, Pan-

ama, and the Dominican Republic) are not party

to it. It facilitates the transit of people from partic-

ipating countries without the need for a passport

but does not include the right to residency.

7

Cartagena Declaration on Refugees, adopted by the Colloquium on the International Protection of Refugees in Central America,

Mexico and Panama, held in Cartagena, Colombia, from November 19 to 22, 1984.

Migration Policy Regimes 20

TABLE 3: Regional and Subregional Instruments

CARIBBEAN

BAHAMAS

ACHR 1969

5 / 11 / 1981

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Accepted

Not

Accepted

Not

Accepted

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Internalized

Not

Internalized

Not

Internalized

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Internalized

Not

Internalized

14 / 9 / 1977 19 / 7 / 1978 12 / 11 / 1987

BARBADOS BELIZE GUYANA HAITI JAMAICA SURINAME TRINIDAD & TOBAGO

San Salvador

1988

28 / 2 / 1990

IACHR

Accepted Accepted Accepted

Cartagena

1984

Internalized

CARICOM

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Accepted

Not

Accepted

Not

Internalized

Not

Internalized

Ratified Ratified Ratified Ratified Ratified

SICA CA-4

Ratified

MERCOSUR

2002

ACHR 1969

Not

Ratified

18 / 8 / 198914 / 8 / 1984

30 / 6 / 2003

26 / 3 / 1985 10 / 8 / 1990

San Salvador

1988

21 / 11 / 1995

IACHR

Accepted Accepted

Cartagena

1984

Internalized Internalized Internalized

Accepted

InternalizedInternalized

Accepted

Ratified

9 / 7 / 1992

8 / 8 / 1996 28 / 5 / 1997

Accepted

Ratified Ratified Ratified Ratified

MERCOSUR

2002

SOUTHERN CONE

ARGENTINA BRAZIL CHILEPARAGUAY URUGUAY

ACHR 1969

20 / 6 / 19782 / 3 / 1970

Not

Accepted

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Internalized

Not

Internalized

2 / 3 / 1981 25 / 9 / 1979 8 / 5 / 1978 21 / 1 / 1978

San Salvador

1988

28 / 10 / 1992

IACHR

AcceptedAccepted

29 / 9 / 1999 4 / 5 / 1995

27 / 4 / 1978

Accepted

30 / 5 / 2000

Accepted Accepted

Cartagena

1984

Internalized

5 / 9 / 1977

Accepted

14 / 9 / 2011

InternalizedInternalized

SICA CA-4

Not

Ratified

Not

Internalized

Ratified Ratified

8 / 3 / 1996

Internalized

Accepted

15 / 12 / 2009

Internalized

Ratified

Ratified

MESOAMERICA + MEXICO

COSTA RICA EL SALVADOR GUATEMALA HONDURAS MEXICO NICARAGUA

PANAMA

DOMINICAN

REPUBLIC

ACHR 1969

Not

Ratified

Not

Ratified

Not

Internalized

8 / 12 / 197728 / 5 / 1973

22 / 10 / 1997

12 / 7 / 1978 1 / 7 / 2019

San Salvador

1988

17 / 5 / 1995

IACHR

Accepted Accepted

Cartagena

1984

Internalized Internalized Internalized

Accepted

Internalized

Accepted

11 / 8 / 2021 11 / 8 / 2021 11 / 8 / 2021 11 / 8 / 2021

Ratified Ratified Ratified Ratified

20 / 6 / 1979

12 / 7 / 2006 10 / 2 / 1993

Accepted

Decisión

878 CAN

MERCOSUR

2002

ANDEAN

ECUADOR PERUBOLIVIACOLOMBIA VENEZUELA

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Migration Policy Regimes 21

2.b.4 Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas Establish-

ing the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and

Including the Single Market, July 5, 2001.

This treaty entered into force on January 1, 2006.

Per article 46, certain categories of nationals of

CARICOM member states have the right to work in

other states. There are currently ten skilled worker

categories. These are: university graduates, artists,

musicians, professional athletes, media workers,

nurses, teachers, artisans with a Caribbean Voca-

tional Qualification (CVQ), domestic workers with

a CVQ or similar certificate, and those holding a

university diploma or vocational training certif-

icate that is comparable to a diploma and was

awarded by a recognized university or institution.

8

All other nationals of member states do not have

the right to work and must follow each country’s

domestic immigration laws. All CARICOM member

states except the Bahamas have ratified the agree-

ment. In other words, the IDB borrowing member

countries to have ratified it are Barbados, Belize,

Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad

and Tobago. However, Haiti does not apply the

free mobility framework to skilled workers.

Findings in regional instruments

There were two major findings. First, as with the

international instruments, there was significant

divergence between the ratification of these in-

struments by the Caribbean states and the other

three subregions. With the exception of Surina-

me, relatively few Caribbean states are parties to

the American Convention on Human Rights and

the Protocol of San Salvador nor recognize the

contentious jurisdiction of the IA Court. Likewise,

Belize is the only state to have incorporated the

expanded definition of “refugee” from the Carta-

gena Declaration in its domestic legislation. The

Dominican Republic is the only state in the other

subregions to follow a similar pattern to the Ca-

ribbean states. At the other end of the spectrum,

13 countries have ratified both conventions, ac-

cepted the jurisdiction of the IA Court, and have

implemented the Cartagena Declaration.

Second, regional freedom of movement agree-

ments have become extremely commonplace

within LAC’s legislative landscape. The excep-

tion in this case is SICA, which only has the Cen-

tral American Free Mobility Agreement. This has

been implemented by merely four of the bloc’s

eight member states and, moreover, is very limit-

ed in scope compared to MERCOSUR, the Andean

Community, or CARICOM agreements.

9

8

For more information, see the report: Caribbean Community Secretariat, CARICOM. Single Market and Economy, Free Move-

ment—Travel and Work, 3rd edition, 2017, p. 20. The following website also contains relevant information (last accessed December

28, 2021): https://gisbarbados.gov.bb/csme/travel/

9

Statistics from the IDB and OECD (2021, p. 27) demonstrate the magnitude of the impact of the MERCOSUR and CARICOM re-

gional mobility mechanisms. The Andean Community migration statute is too recent for data on it to be available yet.

Migration Policy Regimes 22

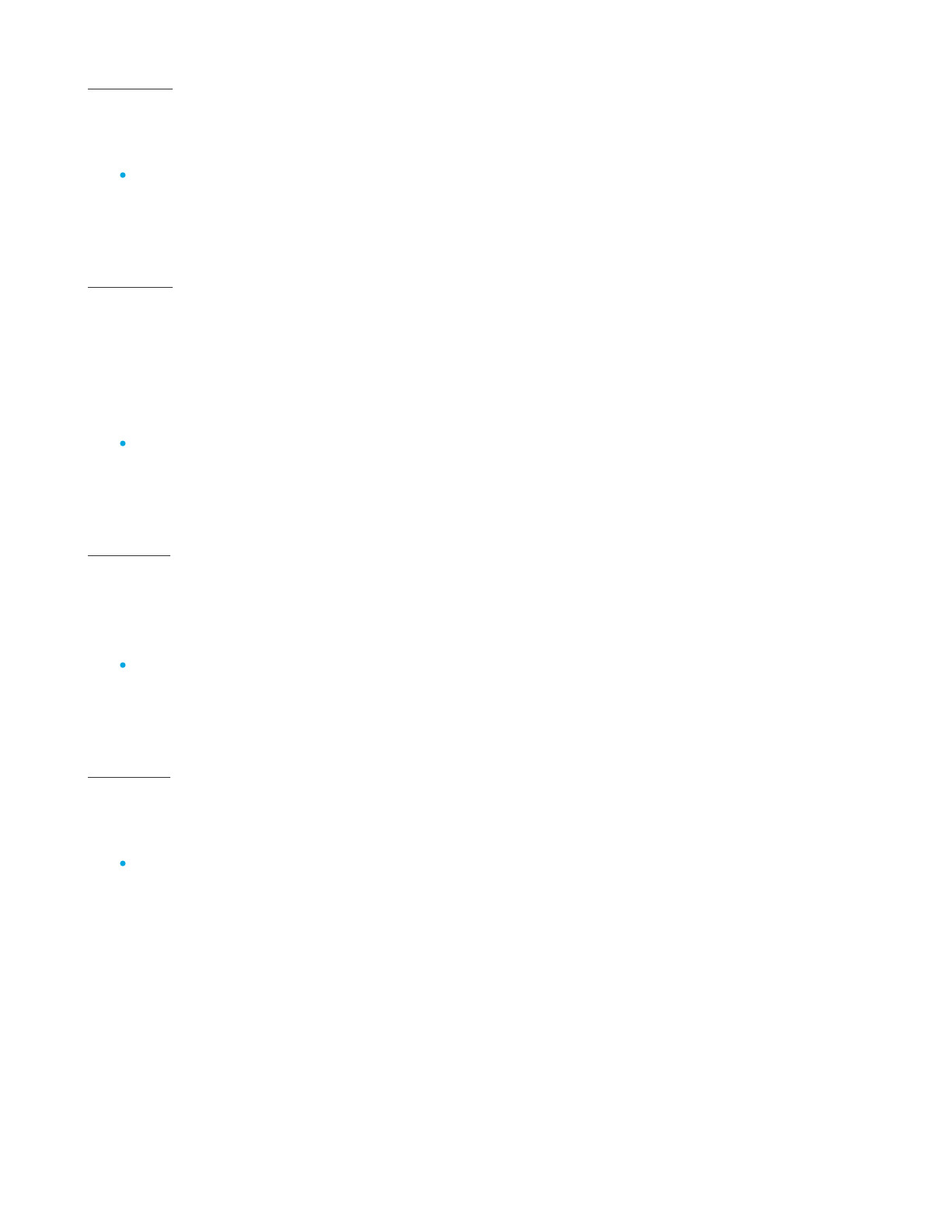

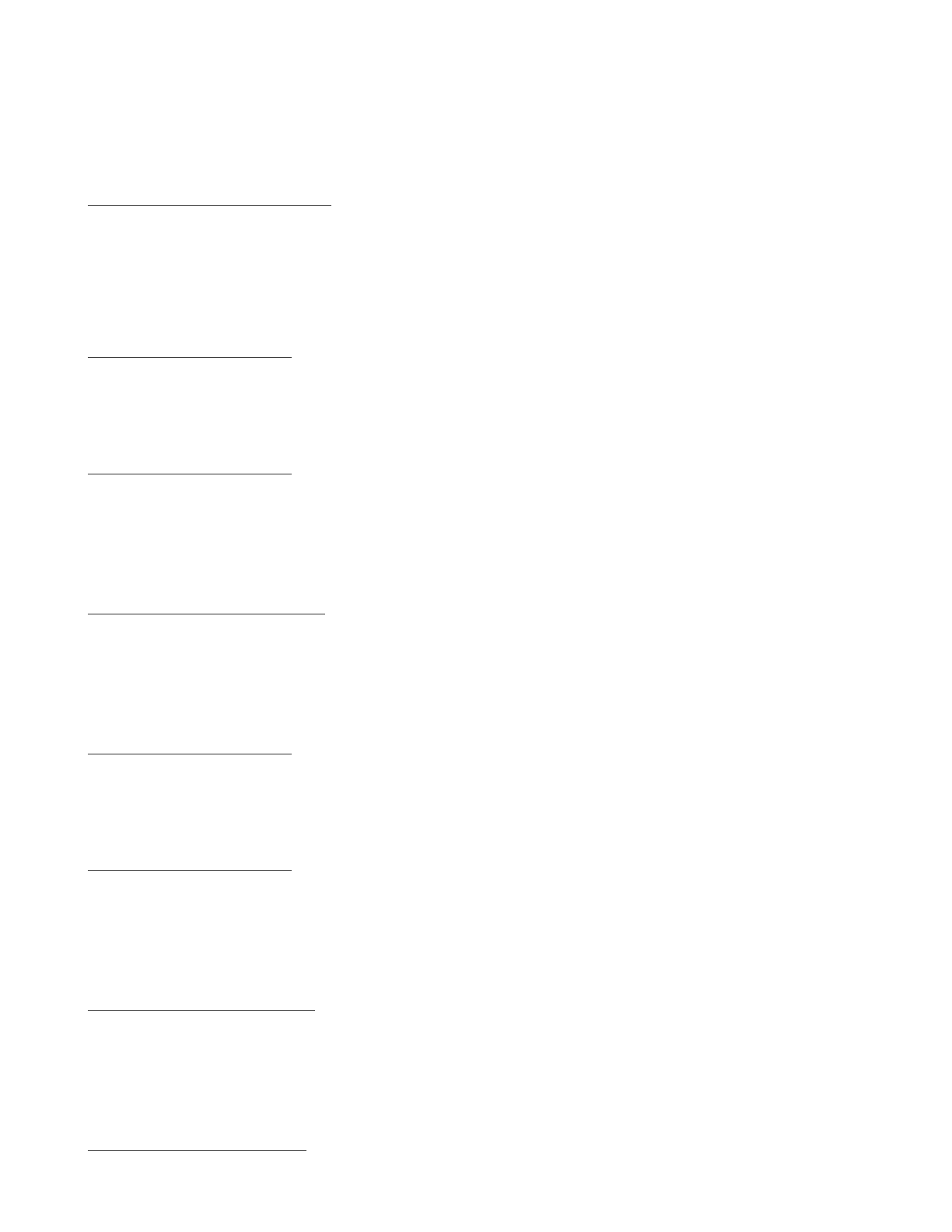

3. Visa-Free Entry

This section explores the citizens of countries that

are required obtain a visa to enter a given country.

The data that it draws on comes mainly from the

ocial websites of the relevant ministries in each

country, usually the ministry of foreign aairs. Our

analysis covers the 26 IDB borrowing member

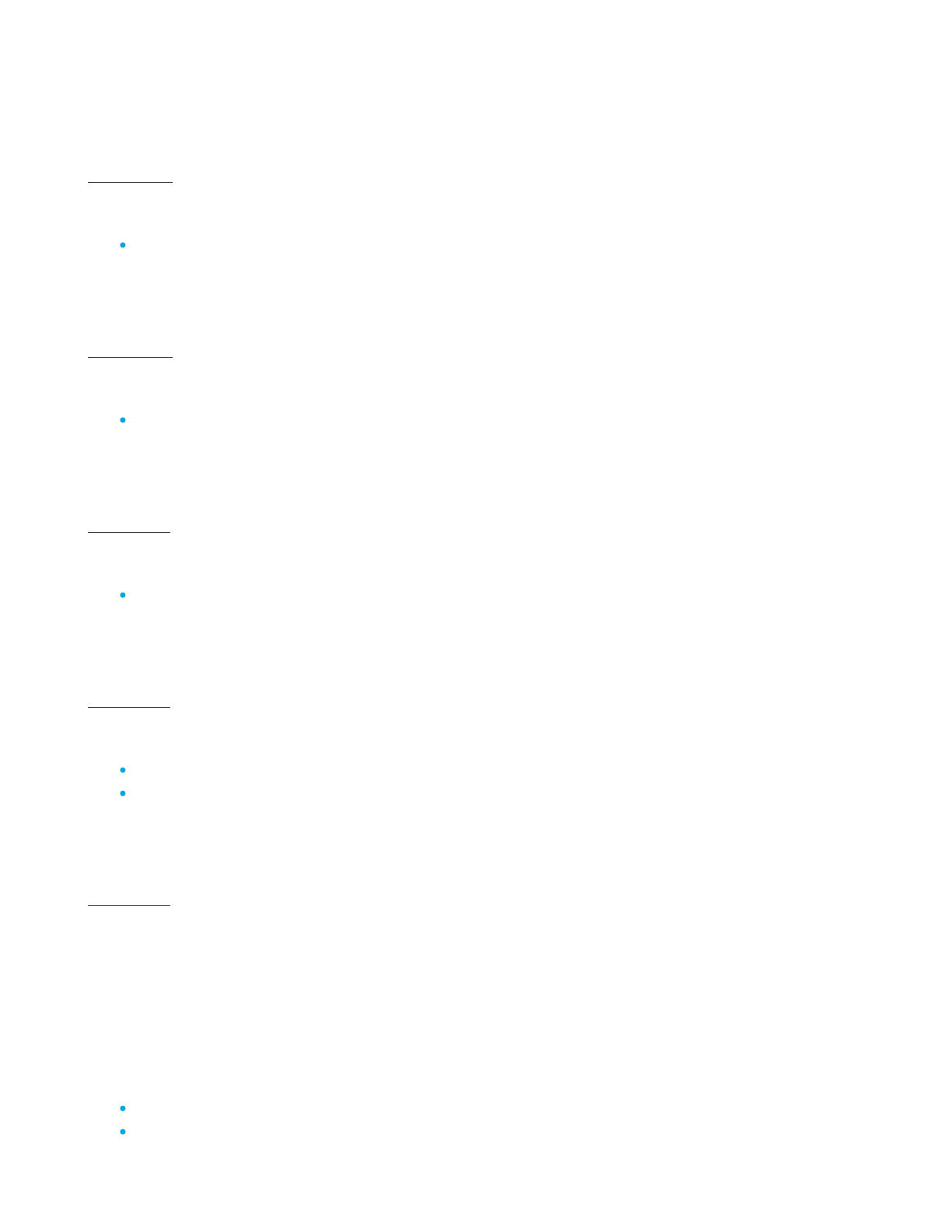

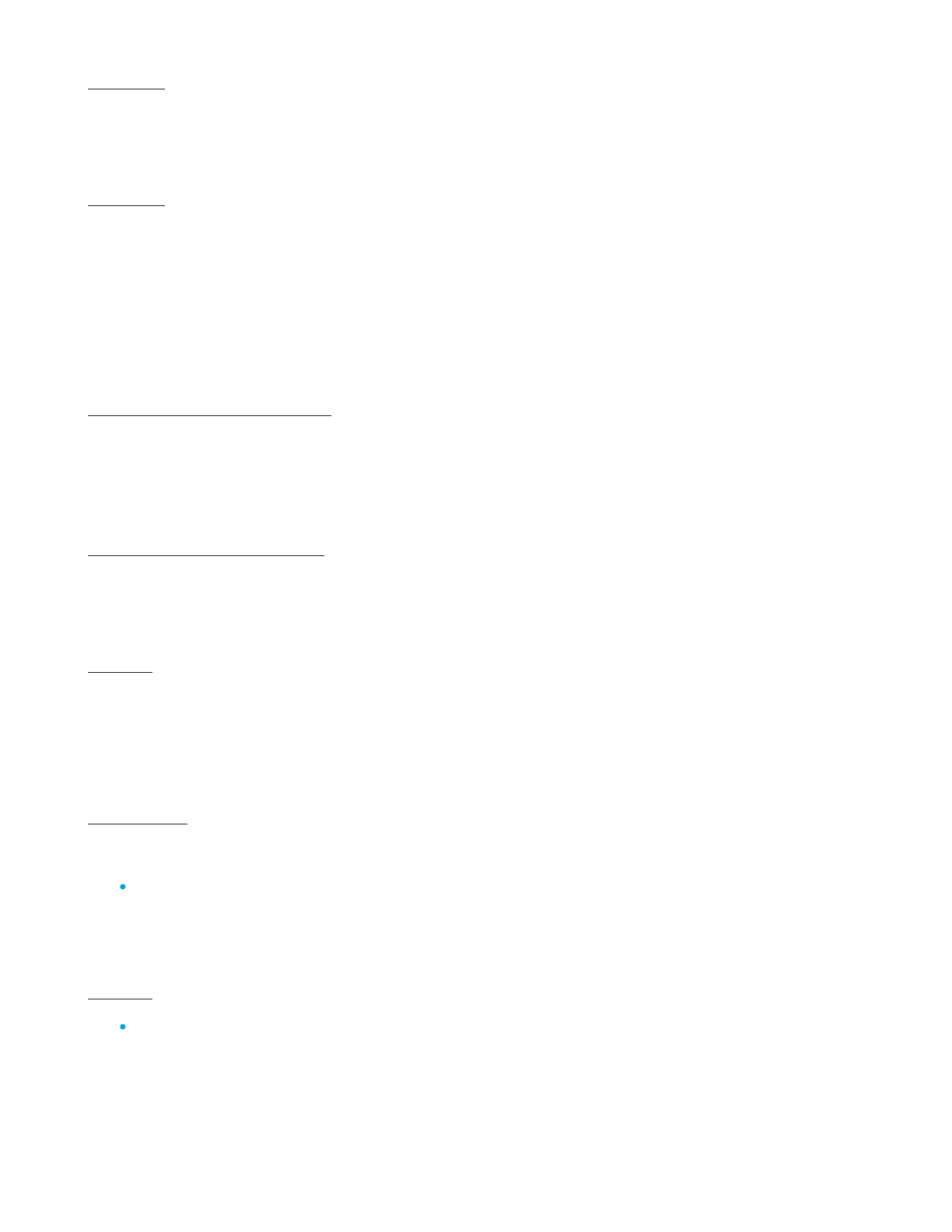

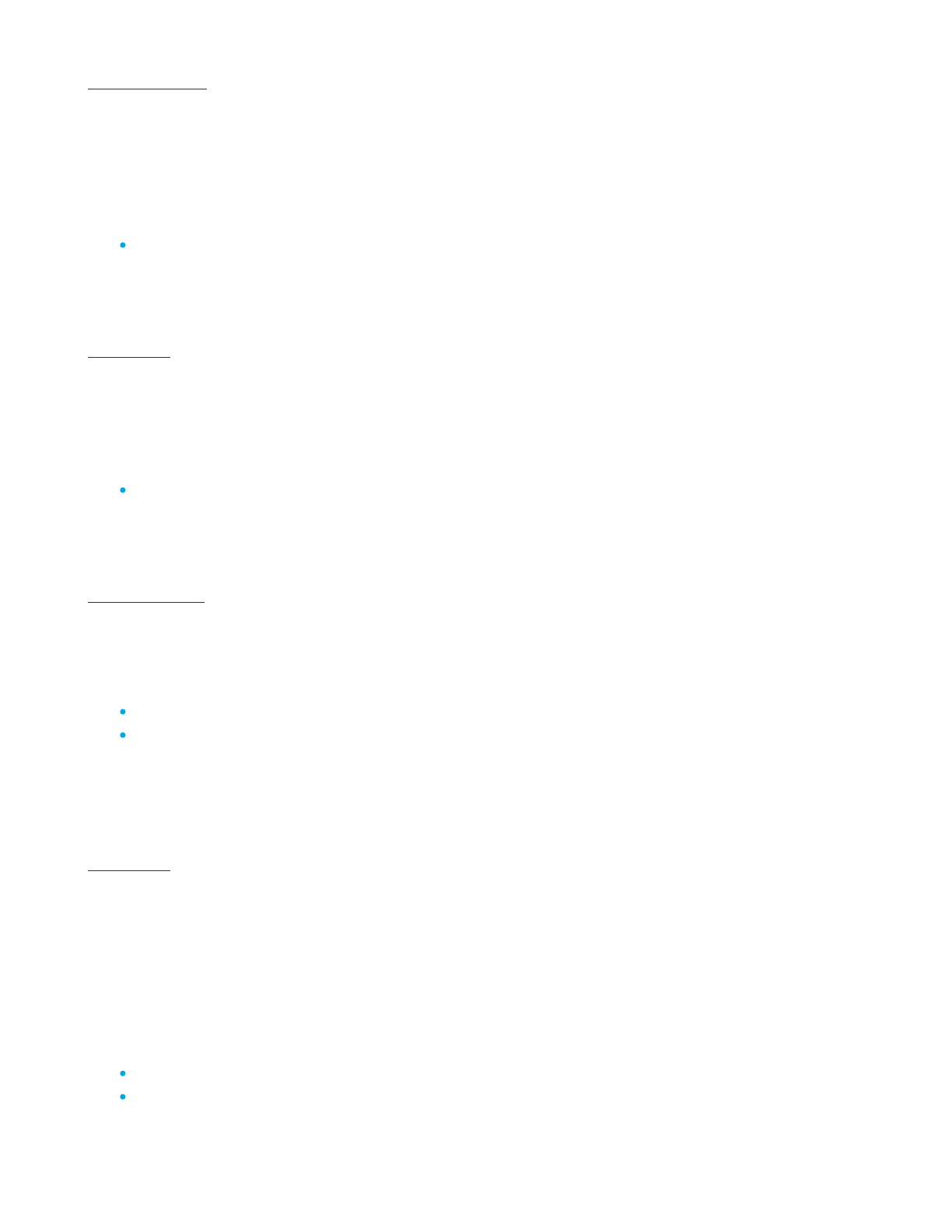

countries. Our main finding is that visa-free move-

ment among LAC countries is commonplace, al-

though conditions vary considerably from coun-

try to country.

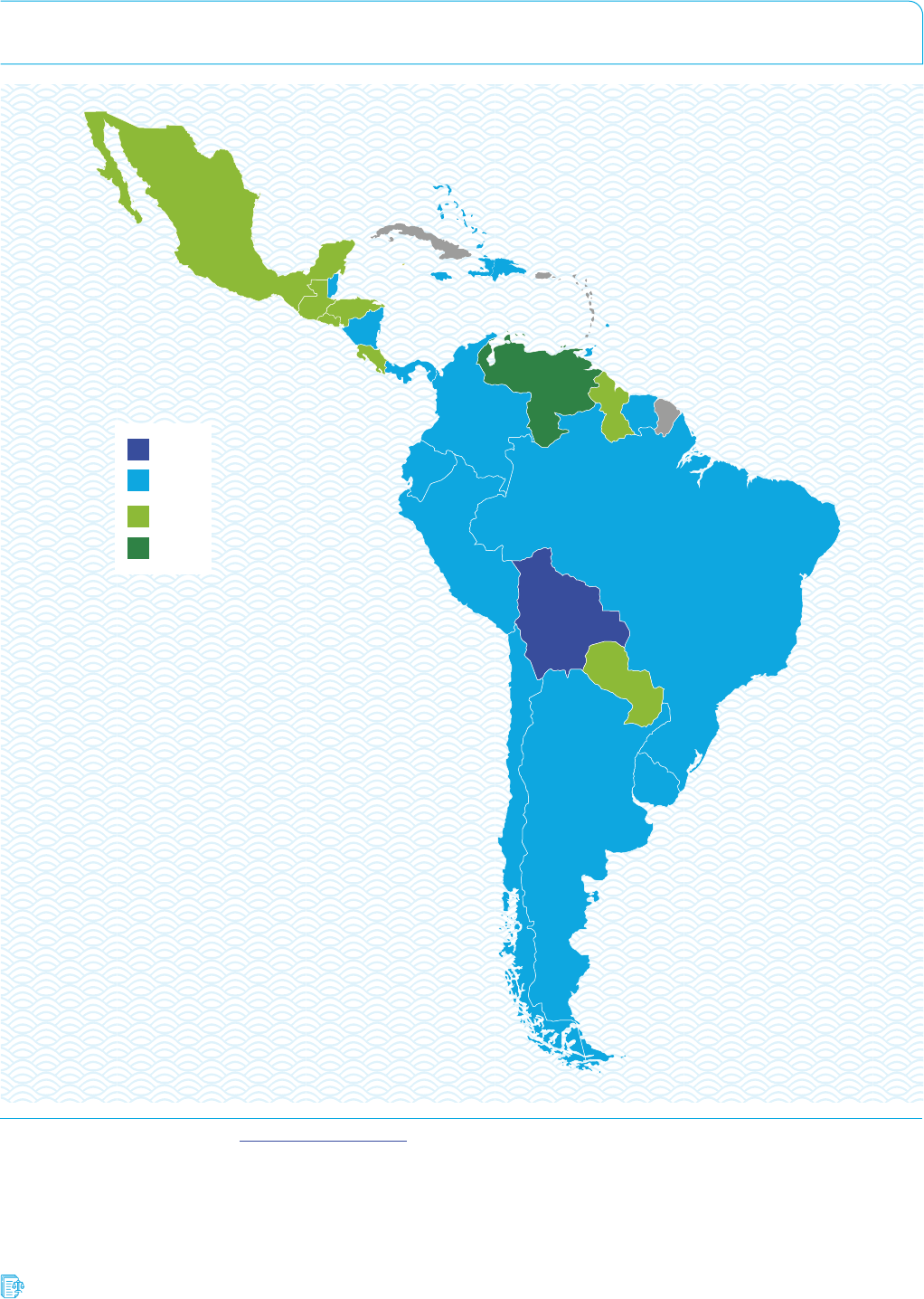

First, the country that requires visas for visiting

nationals from more states in the region than any

other is Venezuela, which requires them for citi-

zens of 11 countries, followed by Mexico with 9 (see

figure 3). Venezuela’s policy in this regard owes to

its application of the principle of reciprocity with

states that require visas for Venezuelan nationals.

As a consequence, it has modified its visa legisla-

tion in the last five years on several occasions to

exclude nationals from several countries from the

benefit of visa-free entry as tourists, such as Pana-

ma in 2017 or Chile and Peru in 2019.

In the case of Mexico, this may be related to the fact

that it is the main country of transit for migrants

seeking to reach the United States. This generates

a significant flow and visas are a mechanism that

may slow it to make it more manageable. Countries

whose citizens must have a visa prior to travelling

to Mexico are those that are most often encoun-

tered attempting to cross into the U.S. without

permission. These include four countries in Central

America (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and

Nicaragua), Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and

Ecuador

10

. Nationals of these countries are among

the most often detained at the US border for at-

tempting to cross without permission

11

.

With respect to the other countries that require

visas of citizens of six or more LAC countries, we

find the countries of the Northern Triangle (El Sal-

vador, Guatemala, and Honduras) and Costa Rica

in Central América, Guyana in the Caribbean, and

Paraguay in South America. In five of these eight

cases, the Guyanese visa requirements seem to be

based on reciprocity, as those eight countries also

require visas for Guyanese. The three exceptions

are El Salvador, Haiti, and Nicaragua. Paraguay

requires visas for nationals of eight countries of

the Caribbean, though this is reciprocal only with

Guyana and Surinam.

10

Joint Foreign Ministry-Government communiqué of Mexico, “México suspende temporalmente exención de visas para nacio-

nales ecuatorianos”, August 20, 2021, available here: https://www.gob.mx/sre/prensa/mexico-suspende-temporalmente-exen-

cion-de-visas-para-nacionales-ecuatorianos-280613?idiom=es (last accessed December 28, 2021).

11

US Customs and Border Patrol had more than 97 thousand encounters with Ecuadorians attempting to cross the US border

without permission in fiscal year 2021. While it is possible that some persons were encountered more than once, this is still

eight times the number of Ecuadorians in similar circumstances in 2020. See https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/nationwi-

de-encounters

Migration Policy Regimes 23

FIGURE 3: Number of Countries in LAC Whose Nationals Are Required to Hold a Visa

to Enter Other Countries

Source: Compiled by the authors. See datamig.iadb.org/law-map.

0

1-5

6-10

>10

MEXICO

BELIZE

THE BAHAMAS

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

BARBADOS

GUYANA

SURINAME

BRAZIL

URUGUAY

ARGENTINA

CHILE

PERU

ECUADOR

COLOMBIA

BOLIVIA

PARAGUAY

VENEZUELA

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO

HAITI

JAMAICA

HONDURAS

NICARAGUA

GUATEMALA

EL SALVADOR

PANAMA

COSTA RICA

Migration Policy Regimes 24

TABLE 4: Number of Countries in LAC Requiring Visas for Nationals of Each Country

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Number of countries

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

9

10

11

24

Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Uruguay

Barbados, Chile, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago

Belize, Colombia, Panama, Peru, Paraguay

Bahamas, Guatemala

Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras

Bolivia, Guyana, Jamaica

Nicaragua

Suriname

Dominican Republic

Venezuela

Haiti

Countries

If the data is analyzed from the point of view of

the number of destination countries that nation-

als of each country can visit without a visa, only

the citizens of Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, and

Uruguay have the privilege of entering all other

borrowing member countries without a visa. Na-

tionals of Barbados, Chile, Mexico, and Trinidad

and Tobago require visas for just one state, and

those of six other countries in two (see table 4).

All other countries except Bolivia require visas for

Haitian nationals, including other countries in the

Caribbean.

Second, several states have introduced visa re-

quirements for Venezuelan nationals in recent

years, namely Honduras and Panama in 2017;

Guatemala in 2018; Chile, Ecuador, the Dominican

12

Mexico and Costa Rica also introduced visa requirements for Venezuelan nationals in January and February 2022, respectively.

13

CARICOM, Thirty-Ninth Regular Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community, Montego Bay,

Jamaica, July 4–6, 2018, p. 12.

Republic, Peru, and Trinidad and Tobago in 2019;

and Nicaragua in 2021

12

(Chaves-González and

Echevarría Estrada 2020; Acosta, Blouin, and Frei-

er 2019).

Another noteworthy point in the case of Haiti is

the uncertain relationship between the right to

freedom of movement that derives from regional

agreements and the application of visa require-

ments. For example, in 2018, the heads of state

and government of the CARICOM countries de-

cided to recognize Haitian citizens’ right to move

to another member state for stays of up to six

months, subject to certain conditions.

13

However,

this right is not being complied with in practice for

various reasons.

Migration Policy Regimes 25

4. Temporary Residency

entered the country regularly before May 2023

(article 4). Bilateral agreements on this matter are

also commonplace in South America and include,

for example, the agreements signed between Ec-

uador and Venezuela (2010), Argentina and Brazil

(2005), and Brazil and Uruguay (2013). The rel-

evant regional treaties include the MERCOSUR,

Bolivia, and Chile Residency Agreement and the

MERCOSUR Residency Agreement, both of which

have been in force since 2009; the Andean Migra-

tory Statute, in force since August 11, 2021; and

Articles 45 and 46 of the CARICOM Revised Trea-

ty of Chaguaramas, which entered into force on

January 1, 2006. These three agreements dier in

terms of scope—in other words, who they apply

to and what rights they entail—but they all facili-

tate the residency of thousands of people in South

America and the Caribbean.

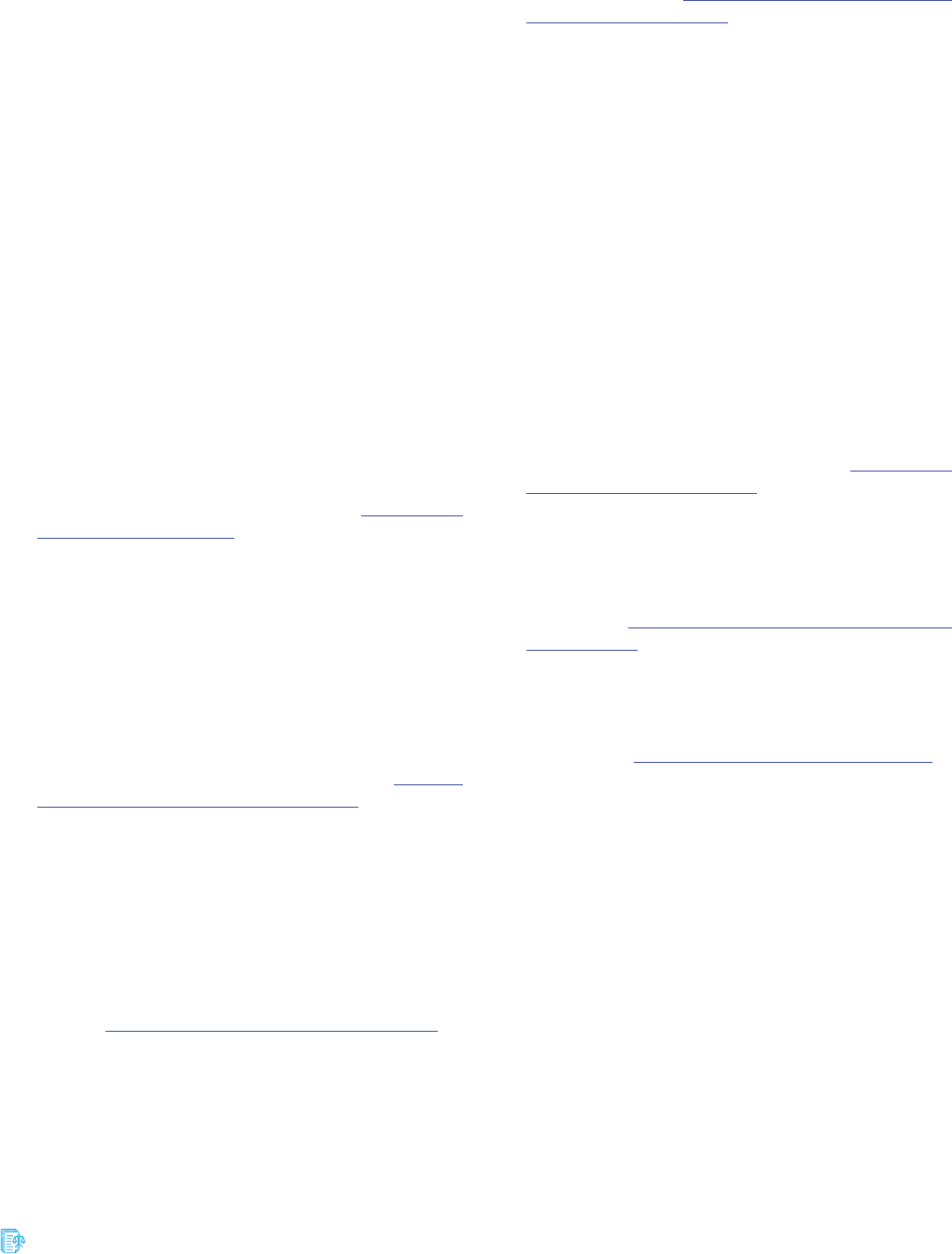

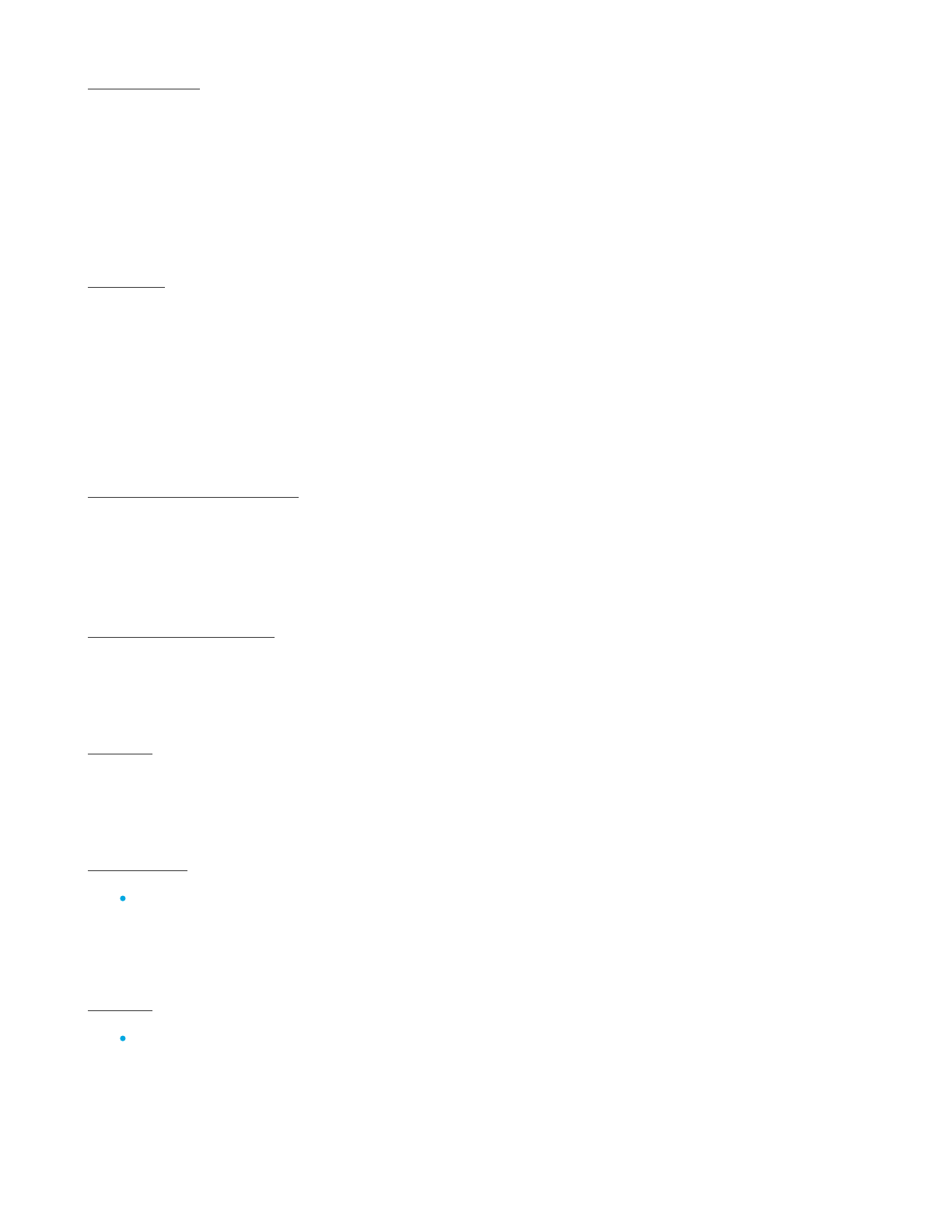

Third, reciprocity is not always a prerequisite.

For example, Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay oer

residency rights to nationals of Guyana, Surina-

me, and Venezuela even though this treatment is

not reciprocal. Brazil also enables Haitian nation-

als to apply for a temporary visa at its Port-au-

Prince Consulate, which can be transformed after

arrival in Brazil into a two-year residency permit

(Fernandes et al. 2013). Likewise, El Salvador al-

lows residency for those who are nationals of oth-

er Central American countries by birth, a privilege

that Salvadorans do not enjoy in these countries.

Finally, several Caribbean countries (e.g., Barba-

dos, Guyana, Jamaica, or Trinidad and Tobago)

give special treatment to citizens of the Bahamas,

or Haiti, or both, even though these countries do

not implement the CARICOM agreement for the

free movement of skilled workers. Consequently,

Colombia’s decision in 2016 not to oer the right

of residency to Chilean nationals due to the lack of

existing reciprocity is not a pattern that is always

observed.

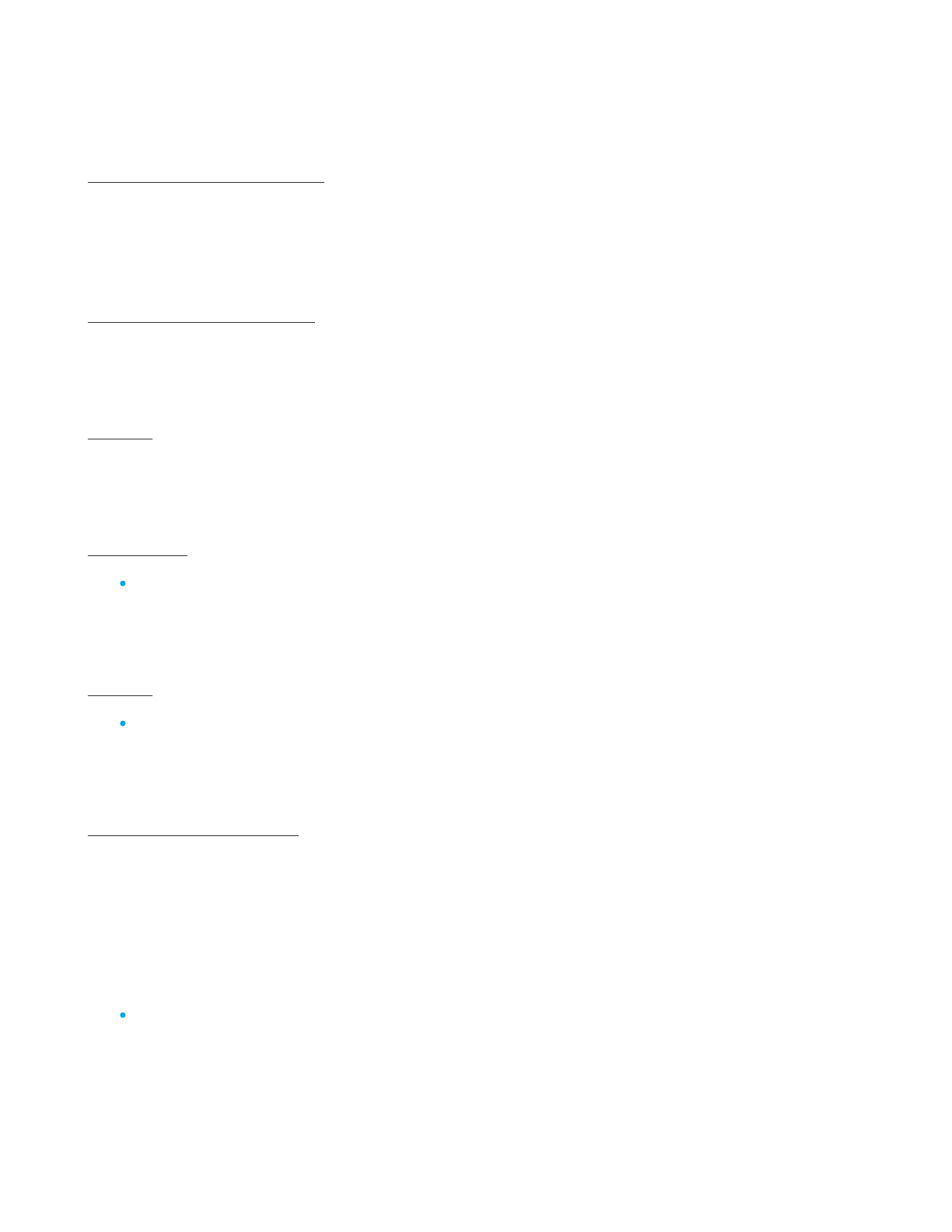

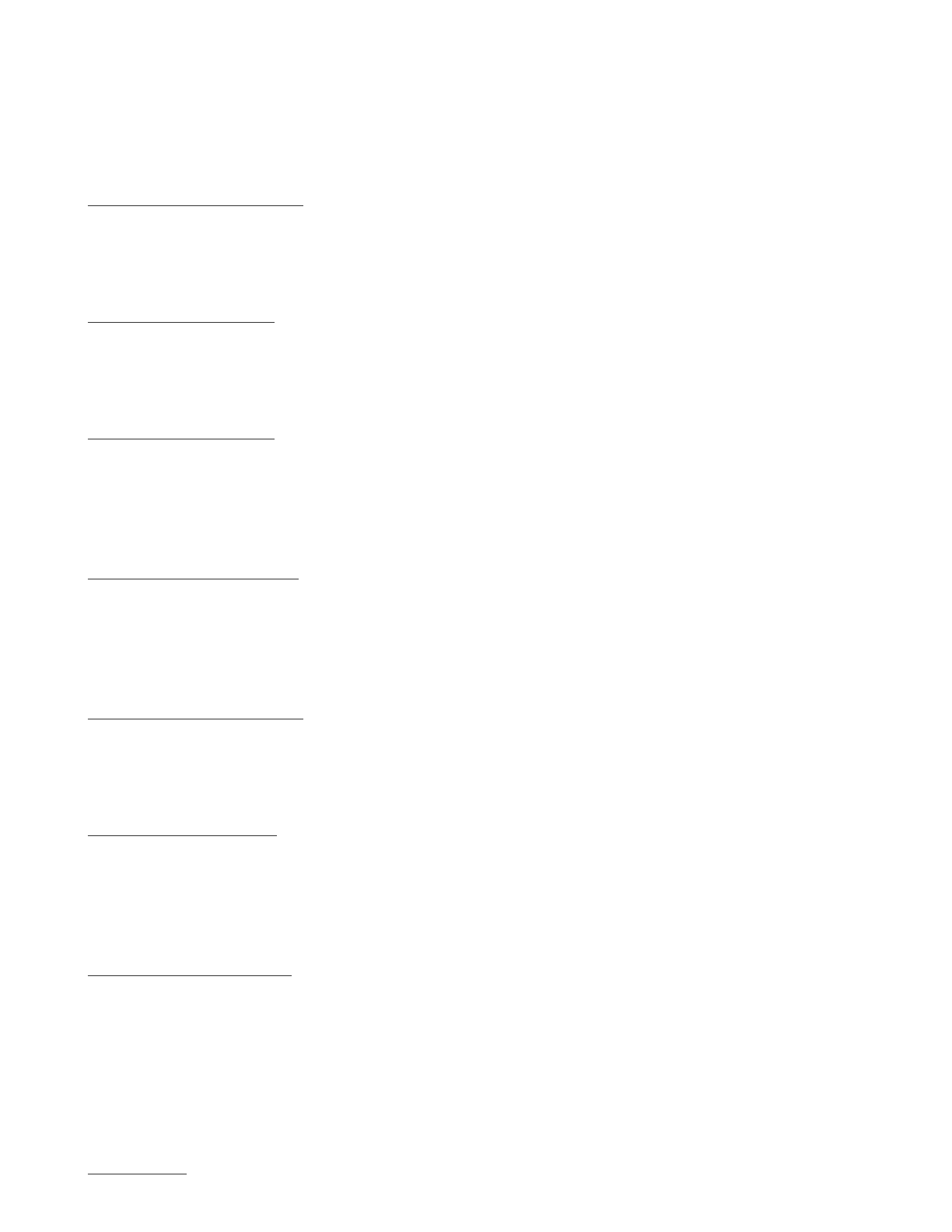

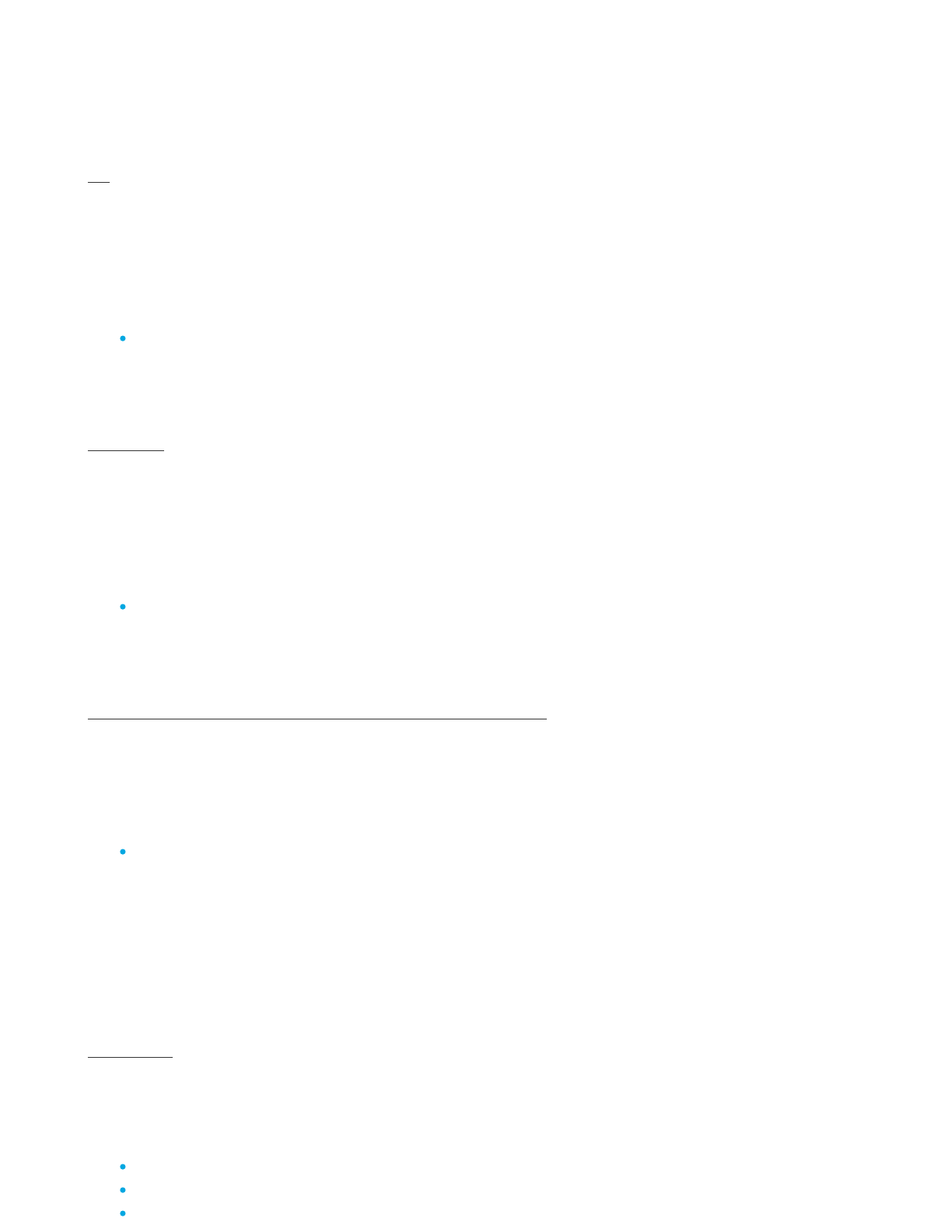

This indicator examines whether a country allows

privileged access to temporary residency for na-

tionals of another state in the region. The main

finding is that free residency clauses have become

commonplace and now exist in the legislation of

17 of the 26 borrowing member countries. That

said, a few points need to be explored in greater

detail.

First, the only countries that do not allow privi-

leged access to residency for nationals of at least

one other country are the Bahamas and Haiti in

the Caribbean, and Costa Rica, Guatemala, Hon-

duras, Nicaragua, Panama, the Dominican Repub-

lic, and Mexico in Mesoamerica. Mexico’s position

is explained by the fact that it is not a party to any

regional agreement with freedom of movement

rules. Likewise, the Bahamas has not ratified the

2001 Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas, while Haiti

does not apply the part concerning the free move-

ment of certain skilled workers despite having rat-

ified it. Finally, the Central American Free Mobility

Agreement that was adopted as part of SICA was

agreed on by only four countries (El Salvador, Gua-

temala, Honduras, and Nicaragua) and is intended

to allow intraregional transit but not residency.

Second, rules facilitating residency can be found

not only in regional agreements but also in bilat-

eral treaties and domestic legislation. For exam-

ple, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and El Salvador

establish residency rights for nationals of certain

countries in the region in their domestic legisla-

tion. This is also the case for Colombia, although

on a temporary basis: Decree 216 of 2021 enables

Venezuelan nationals to request residency if they

4.a Preferential access

to temporary residency

Migration Policy Regimes 26

FIGURE 4: Preferential Access to Temporary Residency

Source: Compiled by the authors. See datamig.iadb.org/law-map.

No

For Regional Migrants

For Regional Migrants

and some others

MEXICO

BELIZE

THE BAHAMAS

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

BARBADOS

GUYANA

SURINAME

BRAZIL

URUGUAY

ARGENTINA

CHILE

PERU

ECUADOR

COLOMBIA

BOLIVIA

PARAGUAY

VENEZUELA

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO

HAITI

JAMAICA

HONDURAS

NICARAGUA

GUATEMALA

EL SALVADOR

PANAMA

COSTA RICA

Migration Policy Regimes 27

TABLE 5: Temporary Residency

CARIBBEAN

BAHAMAS

Preferential

access to

temporary

residence

For some

nationals of

the subregion

For some

nationals of

the subregion

For some

nationals of

the subregion

For some

nationals of

the subregion

For some

nationals of

the subregion

For some

nationals of

the subregion

and some others

BARBADOS BELIZE GUYANA HAITI JAMAICA SURINAME TRINIDAD & TOBAGO

Permanent

regularization

mechanisms

No No

Not

Available

Not

Available

Not

Available

Not

Available

Not

Available

Not

Available

Not

Available

Available

No

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

No

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

No

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

No

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

No

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

No

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

One

extraordinary

regularization

has been

carried out

One

extraordinary

regularization

has been

carried out

Extraordinary

regularization

mechanisms

since 2000

Preferential

access to

temporary

residence

For some

nationals

of South

America

For some

nationals

of South

America

For some

nationals

of South

America

For some

nationals

of South

America

For some

nationals

of South America

and some others

Permanent

regularization

mechanisms

Not

Available

Available Available Available Available

11

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

5

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

2

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

One

extraordinary

regularization

has been

carried out

3

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

SOUTHERN CONE

ARGENTINA BRAZIL CHILEPARAGUAY URUGUAY

Extraordinary

regularization

mechanisms

since 2000

Preferential

access to

temporary

residence

For some

nationals of

the subregion

Permanent

regularization

mechanisms

No No No No No No No

Not

Available

Not

Available

Not

Available

Not

Available

Available Available Available Available

No

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

No

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

9

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

One

extraordinary

regularization

has been

carried out

One

extraordinary

regularization

has been

carried out

3

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

13

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

2

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

MESOAMERICA + MEXICO

COSTA RICAEL SALVADORGUATEMALA HONDURASMEXICO NICARAGUA

PANAMA

DOMINICAN

REPUBLIC

Extraordinary

regularization

mechanisms

since 2000

Migration Policy Regimes 28

Preferential

access to

temporary

residence

For some

nationals

of South

America

For some

nationals

of South

America

For some

nationals

of South

America

For some

nationals

of South

America

For some

nationals

of South

America

Permanent

regularization

mechanisms

Extraordinary

regularization

mechanisms

since 2000

Not

Available

Not

Available

Available Available Available

11

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

12

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

4

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

8

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

3

extraordinary

regularizations

have been

carried out

ANDEAN

ECUADOR PERUBOLIVIA COLOMBIA VENEZUELA

TABLE 5: Temporary Residency (cont.)

Source: Compiled by the authors.

The database distinguishes between two dierent

regularization procedures. Permanent regulariza-

tion mechanisms (4.b) are procedures that are

established by law or in the implementing regu-

lations and that allow any individual to benefit

from them at any time if certain requirements are

met. In contrast, extraordinary programs (4.c), dis-

cussed below, only apply for a limited time and are

normally regulated by means of a decree or ad-

ministrative order issued by the executive.

The main trend that we want to highlight is that

permanent regularization mechanisms have be-

come commonplace in the region and are in place

in 13 countries.

First, most countries have incorporated these

mechanisms as part of the new migration laws