1

Primary Care Respiratory

Update

PCRS position on FeNO testing for

asthma diagnosis

The fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) test

measures the level of NO in the exhaled breath

and provides an indication of eosinophilic inflam-

mation in the lungs. For the diagnosis of asthma,

the British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the Scot-

tish Intercollegiate Guidelines (SIGN) position

FeNO testing after the objective evaluation of air-

ways obstruction and alongside other potential

tests for inflammation such as determination of

blood eosinophil levels, IgE skin-prick test to

detect atopy, and tests for variability (reversibility,

peak expiratory flow [PEF] charting and challenge

tests).

1

Patients with a history and clinical char-

acteristics that support a high probability of

asthma and who have had an objective measure

of reversible airways obstruction do not need

FeNO before progressing to a trial of treatment.

1

Additional objective evidence including FeNO is

recommended as an optional investigation as a

test for eosinophilic asthma for those considered

to have an intermediate probability of asthma.

1

The current PCRS position aligns with the guid-

ance issued by BTS/SIGN. This article reviews

the evidence base and clinical guidelines upon

which the PCRS position is based.

Background

Asthma is a heterogeneous condition character-

ized by respiratory symptoms (wheeze, cough,

breathlessness, chest tightness and pain) asso-

ciated with variable airflow obstruction, hyper-

responsiveness and often an underlying inflam-

mation. There is no single defining feature or

symptom of asthma, however variability is at its

core, so diagnosis is achieved through a holistic

evaluation of patient symptoms over time along-

side repeated physiologic evaluation of lung func-

tion, and assessment of response to trials of

treatment. Pathologic evaluations including tests

for eosinophilic airway inflammation, and other

investigations, may sometimes be needed.

Nitric oxide (NO) is produced in the lungs and

so can be detected in the exhaled breath and

elevated exhaled NO levels are thought to be

related to eosinophilic lung inflammation.

2

Frac-

tional exhaled NO (FeNO) testing is quantitative,

noninvasive, simple and safe and elevated FeNO

may be supportive of a diagnosis of asthma in

untreated individuals presenting with respiratory

symptoms.

3

However, while suggestive, a posi-

tive FeNO test is not conclusive evidence of

asthma. Indeed, eosinophilic lung inflammation

has been suggested to be a contributing factor

to asthma in approximately 50% of cases, with

the remaining 50% of cases not showing evi-

dence of eosinophilic lung inflammation.

4,5

There has been considerable discussion in

recent years regarding the relevance of FeNO

testing in the diagnostic workup of patients pre-

senting with respiratory symptoms for whom a

diagnosis of asthma is suspected. Here we

review the current recommendations for the role

of FeNO testing in the diagnosis of asthma and

explore the benefits, limitations and challenges of

utilising this test in the primary care setting.

How is FeNO testing conducted?

The FeNO test measures the level of NO in the

exhaled breath. FeNO testing is conducted using

a handheld device into which the patient blows

FeNO Testing For Asthma Diagnosis -

A PCRS Consensus

FeNO Testing For Asthma Diagnosis - A PCRS Consensus was commissioned to set out

the PCRS position on the role of FeNO testing within the context of asthma diagnosis.

Carol Stonham Vice chair, Primary Care Respiratory Society and

NHS Gloucestershire CCG and Noel Baxter Chair PCRS Executive

Feno article2.qxp_Layout 1 28/06/2019 09:33 Page 1

2

Primary Care Respiratory

Update

for 10 seconds at 60 litres a minute. A shorter test is available for

children. The result is provided within approximately 1 minute with

a FeNO level ≥35 ppb as a positive test in children and a level

≥40 ppb as a positive test in adults.

6

What are the current recommendations for FeNO

testing for asthma diagnosis?

NICE

In November 2017 the National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence (NICE) issued guidance for the diagnosis, monitoring

and management of asthma.

6

The guidance focuses on objective

testing for the diagnosis of asthma and suggests FeNO evalua-

tion be considered as an objective test alongside spirometry and

peak expiratory flow (PEF) at initial presentation if equipment is

available, and as part of the diagnostic algorithm for both children

over 5 and adults with respiratory symptoms suggestive of

asthma (Box 1).

BTS/SIGN

The 2016 BTS/SIGN guidance takes a pragmatic approach to

asthma diagnosis and recommends that for patients with a

high probability of asthma, a trial of treatment is appropriate.

1

The guideline incorporates FeNO testing as part of the

diagnostic algorithm only for patients with an intermediate

probability of asthma where further evidence is required

(Box 2). Unlike the current NICE guidance, the principle inves-

tigation is to test for airway obstruction and bronchodilator

reversibility on spirometry. FeNO testing is positioned after

spirometric evaluation as an optional investigation to test for

eosinophilic inflammation along side determination of blood

eosinophil level, IgE skin-prick test for detection of atopy, and

tests for variability (reversibility, PEF charting and challenge

tests)

1

if the results of spirometric evaluation are not clear. A

positive FeNO increases the probability of asthma but a

negative test does not exclude a diagnosis of asthma.

Box 1: NICE guidance for the role of FeNO is the evaluation and diagnosis of asthma in children over

5 and adults

6

FeNO in the diagnosis of asthma in children

• Consider a FeNO test in children and young people (aged 5-16 years) if there is diagnostic uncertainty after initial

assessment and they have either:

o Normal spirometry or

o Obstructive spirometry with a negative bronchodilator reversibility test. Regard a FeNO level of ≥35 ppb as

a positive test

•

Suspect asthma in children and young people (aged 5-16 years) if they have symptoms suggestive of asthma and:

o A FeNO level ≥35 ppb with normal spirometry and negative peak flow variability or

o A FeNO level ≥35 ppb with obstructive spirometry but negative bronchodilator reversibility and no variability in

peak flow or

o Normal spirometry, a FeNO level ≤34 ppb and a positive peak flow variability

• Diagnose asthma in children and young people (aged 5-16 years) if they have symptoms suggestive of asthma

and:

o A FeNO ≥35 ppb with normal spirometry and negative peak flow variability or

o Obstructive spirometry and positive bronchodilator reversibility

FeNO in the diagnosis of asthma in adults

• Offer a FeNO test to adults (aged >17 years) if a diagnosis of asthma is being considered. Regard a FeNO level

of ≥40 ppb as a positive test

• Suspect asthma in adults (aged >17) with symptoms suggestive of asthma, obstructive spirometry and:

o Negative bronchodilator reversibility, and either a FeNO level ≥40 ppb, or a FeNO levels between 25 and

39 ppb and positive peak flow variability, or

o

Positive bronchodilator reversibility, a FeNO level between 25 and 39 ppb and negative peak flow variability

• Diagnose asthma in adults (>17 years) if they have symptoms suggestive of asthma and:

o A FeNO ≥40 ppb with either positive bronchodilator reversibility or positive peak flow variability or bronchial

hyperreactivity or

o A FeNO between 25 and 39 ppb and a positive bronchial challenge test or

o Positive bronchodilator reversibility and positive peak flow variability irrespective of FeNO level

Feno article2.qxp_Layout 1 28/06/2019 09:33 Page 2

3

Primary Care Respiratory

Update

Benefits of FeNO testing as part of the diagnostic

workup for asthma

Reliance on physiologic measures of lung function is a point-

in-time measure and as such if patients are asymptomatic on

the day they attend for testing the results may be negative. A

negative result may also be delivered if the test did not achieve

optimal quality due to operational or patient factors. FeNO is

an objective measure of eosinophilic lung inflammation which

is likely to persist even in the absence of overt respiratory

symptoms on a given day.

7-9

At present, data on the cost-effectiveness of FeNO testing in

the primary care setting is limited but early indications suggest

this may be favourable.

10

Although an initial investment in equip-

ment and training is required with ongoing consumable costs,

there may be cost savings associated with correct diagnosis,

reduced referrals to secondary care and reductions in emergency

primary care and accident and emergency visits.

11-14

While not currently recommended in clinical practice guide-

lines, evidence suggests FeNO testing may also be informative

for the ongoing monitoring of patients with asthma with poor

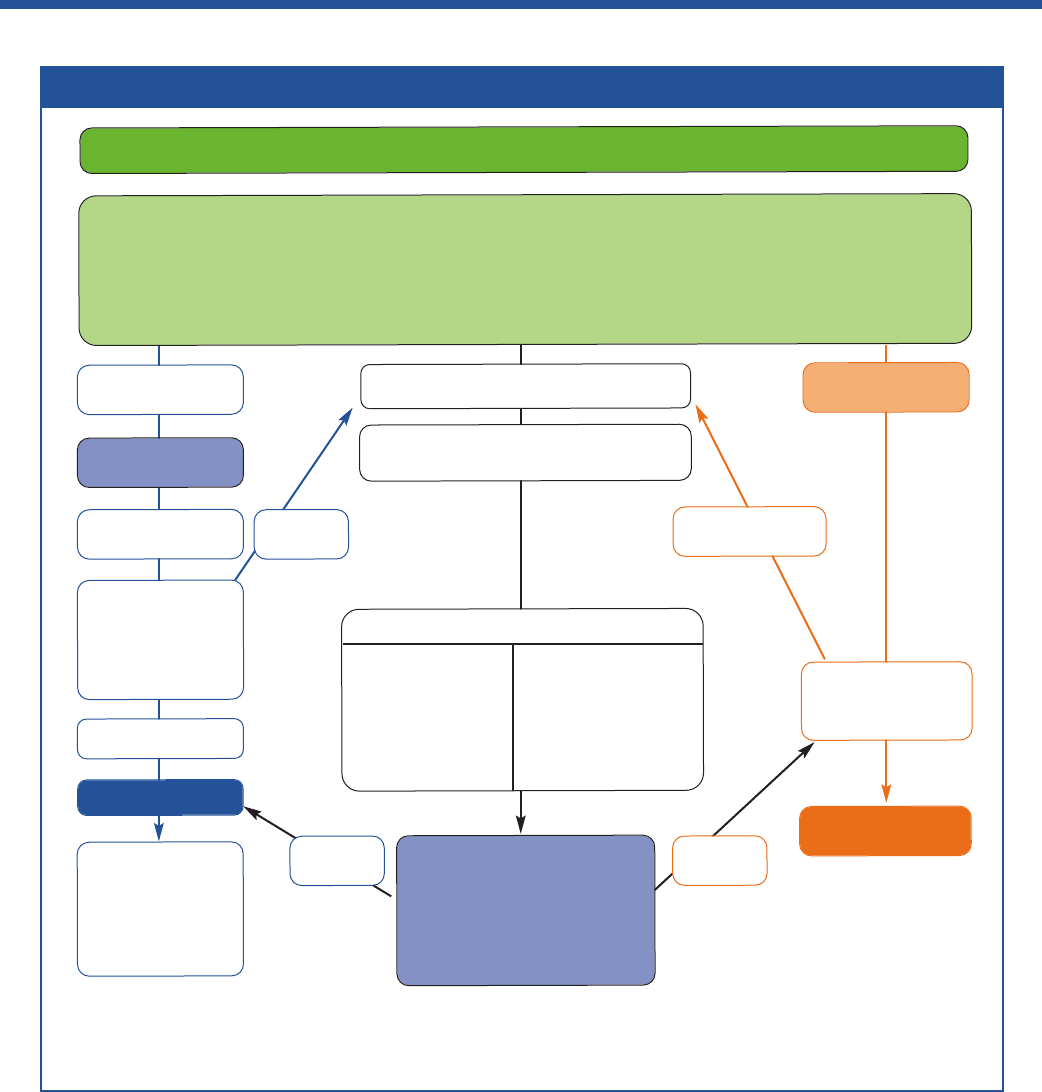

Box 2: The BTS/SIGN diagnostic algorithm for patients presenting with respiratory symptoms

1

Presentation with respiratory symptoms: wheeze, cough, breathlessness, chest tightness*

Structured clinical assessment (from history and examination of previous medical records)

Look for

• recurrent episodes of symptoms

• symptom variability

• absence of symptoms of alternative diagnosis

• recorded observation of wheeze

• personal history of atopy

• historical record of variable PEF or FEV

1

Adjust maintenance

dose. Provide self-

management advice

Arrange on-going

review

High probability

of asthma

Code as:

suspected asthma

Poor

response

Initiation of

treatment

Assess response

objectively

(lung function/

validated symptom

score)

Good response

Asthma

Good

response

Poor

response

Other diagnosis

confirmed

Investigate/treat for

other more likely

diagnosis

Low probability

of asthma

Other diagnosis

unlikely

Intermediate probability of asthma

Test for variability:

• reversibility

• PEF charting

• challenge tests

Test for eosinophilic

inflammation or

atopy:

• FeNO

• blood eosinophils

• skin-prick test, IgE

Options for investigations are:

Test for airway obstruction

spirometry + bronchodilator reversibility

Suspected asthma:

Watchful waiting

(if symptomatic)

or

Commence treatment and

assess response objectively

* In children under 5 years and others unable to undertake spirometry in whom there is a high or intermediate probability of asthma, the options are

monitored initiation of treatment or watchful waiting according to the assessed probability of asthma

Feno article2.qxp_Layout 1 28/06/2019 09:33 Page 3

4

Primary Care Respiratory

Update

control, providing an objective measure of steroid responsiveness

and providing an alert of persistent lung inflammation even in the

absence of evidence of airway obstruction.

9,15

Changes in FeNO

levels may be useful to guide step up and step down of anti-

inflammatory medication and may prompt an evaluation of

adherence and inhaler technique. Having an objective test result

may facilitate opening up a conversation about adherence and

inhaler technique that may be otherwise difficult to approach or

forgotten.

Challenges and limitations of FeNO testing

There is some overlap between FeNO levels among individuals

with and without asthma.

3

An evaluation of the results of eight

studies among adults within the secondary care setting sug-

gested that around 1 in 5 individuals with a positive FeNO test

will not have asthma (false positive) and around 1 in 5 people with

a negative FeNO test will have asthma (false negatives).

1

Data

are lacking for primary care populations. However, as a general

rule, a FeNO level ≥40 ppb is regarded as positive in adults with

a level of ≥35 ppb regarded as positive in children.

1

A variety of factors not related to the pathology of asthma

can result in increased and decreased levels of FeNO, confound-

ing the utility of this test in supporting a diagnosis of asthma

(Box 3).

Understanding these potentially confounding factors and the

potential for false positive and false negative results is essential

to the proper utilization of FeNO testing as part of the diagnostic

workup of patients presenting with respiratory symptoms.

In the general practice setting cost may be a barrier to the

routine use of FeNO testing as part of the work up of patients

presenting with respiratory symptoms suggestive of asthma. The

introduction of Primary Care Networks and new ways of working

with larger populations offers opportunity in primary care beyond

practice level. FeNO is not currently widely available in the UK

and if this test is to be a required component of the diagnostic

workup primary care networks will be required to invest in the

necessary equipment, training (usually provided by the manu-

facturer of the equipment required) and consumables or rely

on referrals to secondary care. Routine FeNO testing for all

patients with asthma may not be a practical approach for all

primary care practices at this time. The NICE 2017 guideline

recommends a FeNO test for all adults presenting with acute

respiratory symptoms suggestive of asthma if equipment is

available and if testing will not compromise treatment of the

acute episode. However, treatment can be initiated for patients

who are acutely unwell at presentation if waiting for objective

tests may compromise treatment of the acute episode.

Objective tests should then be carried out once the acute

symptoms have been controlled. Referral to secondary care

may be made in cases of diagnostic uncertainty. An alternative

to investment in FeNO testing by individual primary care prac-

tices may be a locality-based approach whereby primary care

practices in a given locality or Primary Care Network pool

resources to invest in a FeNO testing service. This approach

is currently being trialled in the UK.

6,16

Conclusions

FeNO testing is a quantitative, non-invasive, simple and safe test

making it suitable for use in the primary care setting with appro-

priate training of health care professional with responsibility for

delivering and interpreting the results.

3

The benefits to patients

are that they do not need to be referred to secondary care for

additional testing as a positive FeNO test alongside respiratory

symptoms and lung function tests suggestive of asthma supports

a diagnosis. However, concerns remain over the necessity for

FeNO testing in every asthma diagnosis and its cost-effective-

ness, and it has been suggested the FeNO testing is more

appropriately placed in diagnostic centres within the community,

intermediate or secondary care setting. Given the current limita-

tions of extending FeNO testing to all patients presenting with

symptoms suggestive of asthma, the current PCRS position

aligns with the guidance issued by BTS/SIGN namely the use of

Box 3: Confounding factors that may result in an increased or decreased FeNO level

1

Confounding factors that may INCREASE

FeNO levels

FeNO levels may be higher than population norms in:

• Men, tall individuals and those consuming a diet high

in nitrates

FeNO levels may be elevated in:

• Patients with allergic rhinitis exposed to an allergen

even in the absence of respiratory symptoms

• Patients with active rhinovirus infection

Confounding factors that may DECREASE

FeNO levels

FeNO levels may be lower than population norms in:

• Children (a lower reference range must be used)

FeNO levels may be reduced in:

• Cigarette smokers

• Patients recently treated with inhaled or oral

corticosteroids

Feno article2.qxp_Layout 1 28/06/2019 09:33 Page 4

5

Primary Care Respiratory

Update

FeNO testing as an optional investigation to test for eosinophilic

inflammation where there is diagnostic uncertainty.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the considered review of this document provided by

our colleagues Hetal Dhruve (Community Pharmacist, London), Deborah Leese

(Pharmacist, Chesterfield) and Laura Rush (Practice Respiratory Lead, Somerset).

Editorial support was provided by Dr Tracey Lonergan.

References

1. BTS/SIGN. SIGN 153. British guideline on the management of asthma.

Published September 2016. Available at: https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/docu-

ment-library/clinical-information/asthma/btssign-asthma-guideline-2016/.

Accessed March 2019.

2. Berry M, Morgan A, Shaw DE, Parker D, Green R, Brightling C, et al.

Pathological features and inhaled corticosteroid response of eosinophilic and

non-eosinophilic asthma. Thorax 2007;62:43-9.

https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2006.073429

3. Dweik RA, Boggs PB, Erzurum SC, Irvin CG, Leigh MW, Lundberg JO, et al.

An official ATS clinical practice guideline: interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide

levels (FeNO) for clinical applications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:

602-15. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.9120-11ST

4. Douwes J, Gibson P, Pekkanen J, Pearce N. Non-eosinophilic asthma:

important and possible mechanisms. Thorax 2002;57:643-8.

https://thorax.bmj.com/content/57/7/643

5. McGrath KW, Icitovic N, Boushey HA, Lazarus SC, Rand Sutherland E, Chinchilli

VM, et al. Asthma Clinical Research Network of the National Heart, Lung, and

Blood Institute: a large subgroup of mild-to-moderate asthma is persistently

noneosinophilic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:612-9.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201109-1640OC

6. NICE. Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. NICE

guideline ng80. Published 29 November 2017. Available at:

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80. Accessed March 2019.

7. Boulet LP, Turcotte H, Plante S, Chakir J. Airway function, inflammation and

regulatory T cell function in subjects in asthma remission. Can Respir J 2012;

19:19-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2012/347989

8. Cano-Garcinuno A, Carvajal-Urena I, Diaz-Vazquez CA, Dominguez-

Aurrecoechea B, Garcia-Merino A, Molla-Caballeron de Rodas P, et al.

Clinical correlates and determinants of airway inflammation in pediatric

asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2010;20:303-10.

http://www.jiaci.org/summary/vol20-issue4-num604

9. Paro-Heitor ML, Bussamra MHCF, Saraiva-Romanholo BM, Martins MA,

Okay TS, Rodrigues JC. Exhaled nitric oxide for monitoring childhood asthma

inflammation compared to sputum analysis, serum interleukins and pulmonary

function. Pediatr Pulmonol 2008;43:134-41. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.20747

10. Harnan SE, et al. Measurement of exhaled nitric oxide concentration in asthma:

a systematic review and economic evaluation of NIOX, MINO, NIOZ VERO and

NObreath. Health Technology Assessment 2015;19.82. Available at:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321828/. Accessed March 2019.

11. Calhoun WJ, Ameredes BT, King TS, Icitovic N, Blkeecker ER, Castro M, et al.

Comparison of physician-, biomarker-, and symptom-based strategies for

adjustment of inhaled corticosteroid therapy in adults with asthma: the BASALT

randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012;308:987-97.

https://doi.org/10.1001/2012.jama.10893

12. Peirsman EJ, Carvelli TJ, Hage PY, Hanssens LS, Pattyn L, Raes MM, et al.

Exhaled nitric oxide in childhood allergic asthma management: a randomised

controlled trial. Pediatr Pulmonol 2014;49:624-31.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.22873

13. Powell H, Murphy VE, Taylor DR, Hensley MJ, McCaffery K, Giles W, et al.

Management of asthma in pregnancy guided by measurement of fraction of

exhaled nitric oxide: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;

378:983-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60971-9

14. Syk J, Malinovschi A, Johansson G, Unden AL, Andreasson A, Lekander M, et al.

Anti-inflammatory treatment of atopic asthma guided by exhaled nitric oxide: a

randomized, controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013; 1:639-48.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2013.07.013

15. LaForce C, Brooks E, Herje N, Dorinsky P, Rickard K. Impact of exhaled nitric

oxide measurements on treatment decisions in an asthma specialty clinic. Ann

Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014; 113:619-23.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2014.06.013

16. Metting EI, Riemersma RA, Kocks JH, Piersma-Wichers MG, Sanderman R,

van der Molen T. Feasibility and effectiveness of an asthma/COPD service for

primary care: a cross-sectional baseline description and longitudinal results.

NPJ primary care respiratory medicine 2015;25.

https://www.nature.com/articles/npjpcrm2014101

Date of Preparation:

June 2019 Version 1

Feno article2.qxp_Layout 1 28/06/2019 09:33 Page 5