THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES

National Academy of Sciences

National Cooperative Highway Research Program

NCHRP PROJECT NUMBER 20-7 (232)

ADA Transition Plans:

A Guide to Best Management Practices

May 2009

Jacobs Engineering Group

Baltimore, MD

Page i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

I INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................................... 1

Background ............................................................................................................................................................. 1

Applicability to State Departments of Transportation .............................................................................................. 1

Purpose of This Guide ............................................................................................................................................ 1

Focus ...................................................................................................................................................................... 2

Methodology ........................................................................................................................................................... 2

Contents of This Guide ........................................................................................................................................... 2

II STEPS to Compliance ................................................................................................................................................ 2

Overview ................................................................................................................................................................. 2

Step 1 - Designating an ADA Coordinator .............................................................................................................. 3

Step 2 - Providing Notice About the ADA Requirements ........................................................................................ 3

Step 3 - Establishing a Grievance Procedure ......................................................................................................... 3

Step 4 - Development of Internal Standards, Specifications, and Design Details ................................................... 4

Step 5 - The ADA Transition Plan ........................................................................................................................... 4

Step 6 - Schedule and Budget for Improvements ................................................................................................... 6

Step 7 - Monitoring the Progress ............................................................................................................................ 7

Conclusion to the Process ...................................................................................................................................... 7

III FINDINGS and Best Practices of State DOTs ........................................................................................................... 7

Overview ................................................................................................................................................................. 7

Administrative Tasks ............................................................................................................................................... 7

Self-Evaluation Phase ........................................................................................................................................... 10

Implementation ..................................................................................................................................................... 12

Sample Transition Plan Outline ............................................................................................................................ 15

Public Involvement ................................................................................................................................................ 16

Coordination With Other Agencies ........................................................................................................................ 17

IV CONCLUSION ......................................................................................................................................................... 18

V FURTHER REFERENCE ........................................................................................................................................ 18

VI ATTACHMENTS ..................................................................................................................................................... 19

List of ADA Contacts by State ............................................................................................................................... 19

Questionnaire........................................................................................................................................................ 32

Page 1

I INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 is a civil rights statute (hereinafter referred to as the Act)

that prohibits discrimination against people who have disabilities. There are five separate Titles (sections) of

the Act relating to different aspects of potential discrimination. Title II of the Act specifically addresses the

subject of making public services and public transportation accessible to those with disabilities. With the

advent of the Act, designing and constructing facilities for public use that are not accessible by people with

disabilities constitutes discrimination.

The Act applies to all facilities, including both facilities built before and after 1990. As a necessary step to a

program access plan to provide accessibility under the ADA, state and local government, public entities or

agencies are required to perform self-evaluations of their current facilities, relative the accessibility

requirements of the ADA. The agencies are then required to develop a Program Access Plan, which can be

called a Transition Plan, to address any deficiencies. The Plan is intended to achieve the following:

(1) identify physical obstacles that limit the accessibility of facilities to individuals with disabilities,

(2) describe the methods to be used to make the facilities accessible,

(3) provide a schedule for making the access modifications, and

(4) identify the public officials responsible for implementation of the Transition Plan.

The Plan is required to be updated periodically until all accessibility barriers are removed.

APPLICABILITY TO STATE DEPARTMENTS OF TRANSPORTATION

The requirements of the ADA apply to all public entities or agencies, no matter the size. The transition plan

formal procedures as outlined in 28 C.F.R. section 35.150 only govern those public entities with more than 50

employees. The obligation to have some planning method to make facilities ADA-accessible is required for all

public entities. This includes State Departments of Transportation (hereinafter referred to as Departments) and

the extensive public transportation systems that they manage. The development or updating of a Transition

Plan is now an ongoing activity or a goal at many Departments. A principal challenge of this activity to the

Departments, as opposed to other government agencies that manage public facilities, is the need to cope with

the overall size and geographic extent of the public facilities that a Department of Transportation manages.

These public facilities can involve thousands of miles of public rights-of-way.

PURPOSE OF THIS GUIDE

The purpose of this guidance document is to ensure that good ideas, helpful information, and successful

practices concerning the development and updating of Transition Plans are recognized, recorded, and shared

among Departments of Transportation.

Page 2

FOCUS

ADA Transition Plans are required from all Departments to cover all facilities under their control. This includes

rights-of-way, but also the buildings that may be owned by the Department such as district offices, welcome

centers, rest stops, airport terminals, and other types of buildings associated with transportation activities. The

focus of this report is solely on Department managed pedestrian facilities in public rights-of-way. This typically

includes sidewalks, pedestrian paths, curb ramps, street crossings, driveway crossings, crosswalks, median

crossings, public transit stops, and pedestrian activated signal systems. The accessibility of pedestrian

facilities in the public right-of-way is only one aspect for providing equal access to state government programs,

services, and activities – but it is an aspect that affects many citizens in their daily activities.

METHODOLOGY

The material in this report is based on information obtained through Department websites, questionnaires filled

out by some Departments, and telephone interviews with the ADA coordinator or other contacts at some

Departments as well as input from guidance documents from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the

Department of Justice (DOJ), and the US Access Board. All contacts were made with the understanding that

individual state status, progress, or data would not be reported or compared, but that any information obtained

would be used in an effort to help other Departments comply with the development and updating of their own

Transition Plans.

CONTENTS OF THIS GUIDE

This report presents the issues that Departments have to deal with in the development and updating of their

ADA Transition Plans. It then describes, using anecdotal information, the roadblocks encountered in dealing

with these issues and the methods that Departments across the country have developed to make progress.

II STEPS TO COMPLIANCE

OVERVIEW

The ideal scenario for meeting the requirements of the Act with regard to the accessibility of facilities in the

public right-of-way would involve the following steps:

(1) designating an ADA Coordinator,

(2) providing notice to the public about ADA requirements,

(3) establishing a grievance procedure,

(4) developing internal design standards, specifications, and details,

(5) assigning personnel for the development of a Transition Plan and completing it,

(6) approving a schedule and budget for the Transition Plan, and

(7) monitoring the progress on the implementation of the Transition Plan.

The following is an expansion on each of the requirements for this ideal scenario.

Page 3

STEP 1 - DESIGNATING AN ADA COORDINATOR

Each Department must designate at least one responsible employee to coordinate ADA compliance. The

benefits of having an ADA Coordinator are that:

It makes it easier for members of the public to identify someone to help them with

questions and concerns about disability discrimination,

It provides a single source of information so questions by the Department staff and from

outside the Department can be answered quickly and consistently, and

It provides an individual who can focus on and who can be instrumental in moving

compliance plans forward.

The person who is appointed to this position must be familiar with the Department’s operation, trained in the

requirements of the ADA and other laws pertaining to discrimination, and able to deal effectively with local

governments, advocacy groups, and the public. It is assumed that the coordinator is given sufficient time free

of other responsibilities to carryout the Coordinator’s functions. Possible locations for the position within a

Department are the Office of the Commissioner, the Civil Rights Office, the Legal Department, the Planning

Department, or the Public Involvement Department.

STEP 2 - PROVIDING NOTICE ABOUT THE ADA REQUIREMENTS

A Department must provide public notice about the rights of the public under the ADA and the responsibility of

the Department under the ADA. Providing notice is not a one time requirement, but a continuing responsibility.

The audience of those who may have an interest in accessibility on Department facilities might include a large

number of individual citizens that would be not be readily identifiable. Groups that are likely to include the

target audience include public transit users and advocacy groups. A Department has the responsibility to

determine the most effective way to provide notice. A notice on a Department website lends itself to both the

requirement for wide notice and the requirement for continuing notice. The website must in itself be

accessible. The Department of Justice has provided a model that could be followed by Departments on their

website. See “Notice under the Americans with Disabilities Act” on their web page,

http://www.ada.gov/pcatoolkit/chap2toolkit.htm, for more information.

Public Outreach Programs The opportunity for the disabled community and other interested parties

to participate in developing the Transition Plan is an integral part of the process. The dissemination of

information and requests for comments can take place through awareness days, newsletters, and

websites. The ability to comment must be linked with public access to information databases.

Possible sources of input to the Transition Plan are activists, advocacy groups, general citizens,

organizations that support the rights of the disabled, elected officials, other agencies, a Governor’s

Committee on People with Disabilities or other such body, or a state ombudsman. Comments can be

obtained through comment forms at meetings, transcriptions of meetings, a dedicated hotline, an e-

mail address, or a postal address.

STEP 3 - ESTABLISHING A GRIEVANCE PROCEDURE

A Department is required to adopt and publish procedures for resolving grievances arising under Title II of the

ADA. The procedures are intended to set out a system for resolving complaints of disability discrimination in a

Page 4

prompt and fair manner. Complaints would typically be directed to the Department’s Office of Civil Rights. It is

generally thought that filing a complaint with a Department is an appropriate first step, in that it provides an

opportunity to resolve a local issue at the local level. However, the exhaustion of a Department’s grievance

procedure is not a prerequisite to filing a complaint with either a federal agency or a court. The Department of

Justice has provided a model for Departments to follow. See “Grievance Procedure under the Americans with

Disabilities Act” at http://www.ada.gov/pcatoolkit/noticetoolkit.pdf for more information.

STEP 4 - DEVELOPMENT OF INTERNAL STANDARDS, SPECIFICATIONS, AND DESIGN DETAILS

The Architectural and Transportation Barrier Compliance Board (alternatively called the Access Board) has

developed accessibility guidelines for pedestrian facilities in the public right-of-way. The Federal Highway

Administration has recognized these as its currently recommended best practices. A Department can adopt

these accessibility guidelines into their own system of standards, specifications, and design details with

modifications to meet local conditions. Development of design standards and design details within the

Department allows for consistency in the application of ADA requirements for new facilities. See

http://www.access-board.gov/prowac/guide/PROWGuide.htm for more information

STEP 5 - THE ADA TRANSITION PLAN

The Transition Plan (hereinafter referred to as the Plan) should consist of the following elements:

1. A List of Physical Barriers in the Department’s Facilities that Limit Accessibility of Individuals with

Disabilities (the Self-Evaluation),

2. A Detailed Description of the Methods to Remove these Barriers and Make the Facilities Accessible,

3. A Schedule for Taking the Necessary Steps,

4. The Name of the Official Responsible for Implementation,

5. A Schedule for Providing Curb Ramps, and

6. A Record of the Opportunity Given to the Disability Community and Other Interested Parties to

Participate in the Development of the Plan.

Periodic updates to the Transition Plan are required in order to ensure on-going compliance. Some of these

key steps are described further below.

The Self-Evaluation The first task involved in preparing an ADA Transition Plan is conducting an

inventory of existing physical barriers in the facilities operated by the Department and listing all the

barriers that limit accessibility. This is often referred to as the self-evaluation process. Possible

inventory approaches are on-ground surveys, windshield surveys, aerial photo studies, or drawing

reviews. Deficiencies very likely to be found in an inventory of facilities are:

Page 5

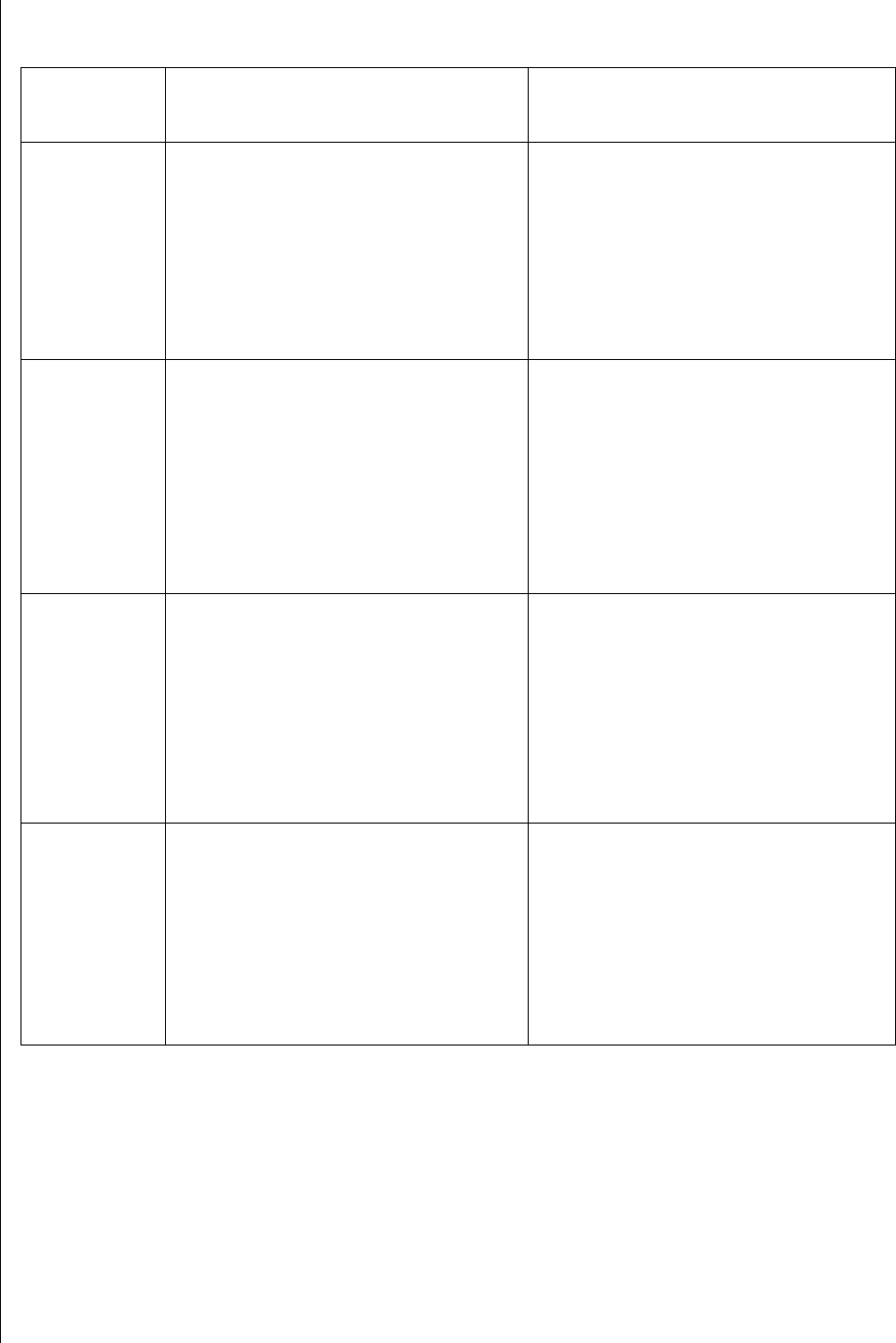

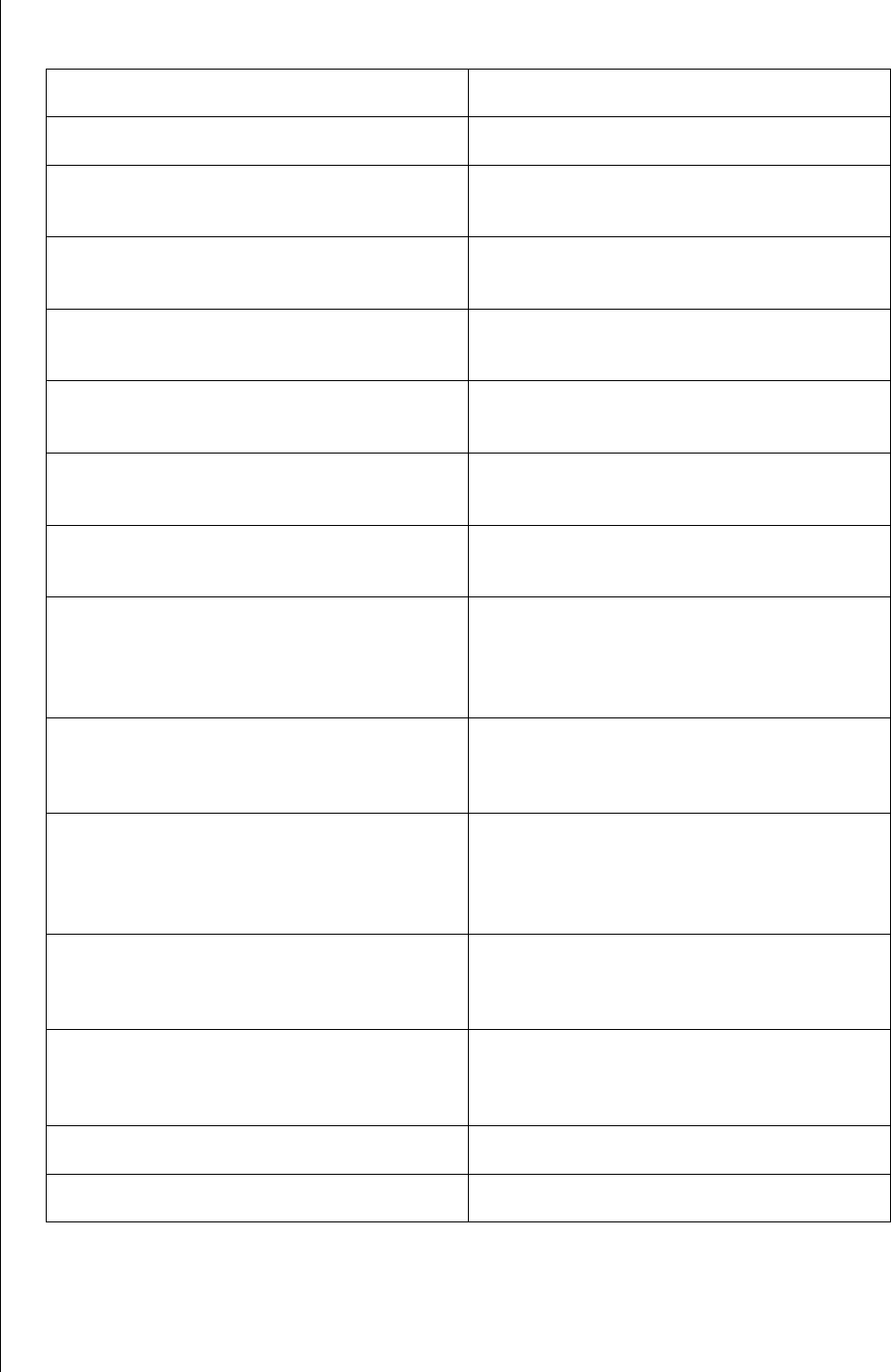

SELF-EVALUATION CHECKLIST

ISSUE

POSSIBLE BARRIERS

Sidewalk and Pathway Clear Width

Narrow, Below Guidelines

Sidewalk and Pathway Cross Slope

Steepness, Irregularity, Variability, Warping

Landings Along Sidewalks and

Pathways

Less Than 4 feet by 4 feet

Sidewalk and Pathway Grade

Steepness, Angle Points

Materials and Finishes

Deterioration of Surfaces, Deterioration of Markings,

Appropriateness of material (ex. Cobblestones)

Gratings

Grating Type, Grate Opening Orientation

Discontinuities

Missing Sections, Gaps, Drops, Steps

Detectable Warning System

Missing, Inappropriate Materials, Inadequate Size, Wrong

Location

Obstructions

Signs, Mail Boxes, Fire Hydrants, Benches, Telephones,

Traffic Signal Poles, Traffic Signal Controller Boxes,

Newspaper Boxes, Drainage Structures, Tree Grates,

Pole Mounted Objects, Standing Water, Snow or Ice

Traffic Signal Systems

Lack of Provision for the Visually Impaired such as APS,

Inadequate Time Allowed, Inoperable Buttons,

Inaccessible Buttons

Curb Ramp

Missing, Doesn’t Fall within Marked Crosswalk, Doesn’t

Conform to Guidelines

Curb Ramp Flares

Missing Where Required, Too Steep

Standards set for each of these issues can be found in the US Architectural and Transportation Barriers

Compliance Board’s Accessible Rights-of-Way: A Design Guide, Chapter 3 “Best Practices in Accessible

Rights-of-Way Design and Construction”. Refer to their website at http://www.access-

board.gov/prowac/guide/PROWGuide.htm for more information.

The information developed through the inventory process has to be quantified and presented as a baseline so

that progress can be monitored and measured. The inventory information can be presented in a variety of

ways including Aerial Photos, a Database or Spreadsheet, Marked Up Drawings, or a Geographic Information

System (GIS).

Page 6

Self-evaluation also takes place after the Transition Plan is complete. Periodic reviews and updates to the

Plan must be conducted to ensure ongoing compliance with ADA requirements. Self-evaluation activities

would then consist of reviewing the Plan to determine the level of compliance, and determine if any additional

areas of upgrade are needed. If deficiencies are found, these are catalogued and the Transition Plan updated

to detail how and when the barriers to pedestrian access would be removed.

STEP 6 - SCHEDULE AND BUDGET FOR IMPROVEMENTS

The Transition Plan should include a schedule of improvements to upgrade accessibility in each year following

the Transition Plan. Remediation work can be presented for an independent remediation program or as an

integral part of regularly scheduled maintenance and improvements project such as Resurfacing Projects,

Roadway Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Projects, and Signal System Installation Projects. All new projects,

regardless of funding sources, would include pedestrian elements that are consistent with the ADA guidelines.

Funding Sources The most immediate source of funds for remediation efforts is the incorporation of

improvements into existing programmed remediation projects, incorporation into programmed

signalization projects, and incorporation into programmed maintenance work. An accessibility

improvement program could be developed as a stand alone project through the Transportation

Improvement Program. Potential sources of funding for accessibility improvements also include the

following:

o Congestion Mitigation/Air Quality Program,

o Highway Safety Improvement Program,

o National Highway System Improvements Program,

o Railway – Highway Crossing Program,

o Recreational Trail Program,

o Safe Routes to School Program,

o State and Community Traffic Safety Program,

o Surface Transportation Program,

o Transportation Enhancement Activities Program.

Additional federal funding sources for different elements of pedestrian projects and programs can be found at

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/civilrights/ada_qa.htm#q30.

Prioritization The prioritization of improvements that may not be included in an existing programmed

project can be based on a number of factors. Generally, priority should be given to transportation

facilities, public places, and places of employment. Other factors to consider when prioritizing

improvements may include:

o Citizen requests or complaints regarding inaccessible locations,

o Pedestrian level of service,

o Population density,

o Presence of a disabled population,

o Cost

Page 7

STEP 7 – MONITORING THE PROGRESS

In order to be effective, the Transition Plan needs to be utilized in yearly planning of projects and funding

decisions, and also needs to be periodically reviewed for compliance and validity. The Transition Plan should

be viewed as a “living document” and updated regularly to reflect changes in real world conditions and to

address any possible new areas of noncompliance. Changes to a sidewalk such as the installation of a

newspaper vending machine, or the relocation of a light pole, can create new access problems that were not

evident when the plan was drafted. Regular updates to the plan will also result in monitoring compliance and

the effectiveness of priorities set in the Plan itself.

CONCLUSION TO THE PROCESS

The ideal conclusion to the Transition Plan process is the elimination of the barriers listed in the Transition

Plan and the acceptance of the requirements of the Act as an everyday reality in all future work going forward.

Due to the magnitude of the task and the other priorities that a Department faces, the ideal scenario has not

universally played out. Although the majority of Departments contacted had some form of inventory or

Transition Plan completed, many of the Departments reported that they were either just beginning the process

or didn’t have firm plans for preparing a Transition Plan.

The following sections of this Guide discuss best practices and decisions that Departments have utilized in

dealing with implementation issues and the methods that they have used to make progress. In addition to

presenting anecdotal evidence from the states in Best Practices, the following sections present “keys to

success”. These are called out to help Departments as they are undertaking the ADA tasks associated with

drafting and updating a Transition Plan.

III FINDINGS AND BEST PRACTICES OF STATE DOTS

OVERVIEW

Each of the fifty state Departments of Transportation as well as those in Puerto Rico and the District of

Columbia were included in this study to gather information on Best Practices used among the states for

completing tasks associated with ADA requirements. All Departments have web sites available for review. A

questionnaire was developed to facilitate the information gathering process from the Departments. This

questionnaire was e-mailed to each of the Departments. The questionnaire was followed up with a telephone

survey to aid in the information exchange. Of the 52 Departments contacted, 20% completed the

questionnaire, 44% were contacted by phone for discussion but with no formal survey completed, and 13%

were not successfully contacted. The remaining 23% of the Departments have indicated that the questionnaire

will be forthcoming, but as of the date of this report, their completed questionnaires have not been received.

The questionnaire is included as an attachment.

ADMINISTRATIVE TASKS

Departments were found to vary greatly in their responsibilities, their structure, and the nature of the facilities

that they manage. Nevertheless, they all have the responsibility of establishing a basic program to meet the

administrative requirements of the ADA. The basic administrative requirements of this program are:

Page 8

(1) Designating an ADA Coordinator,

(2) Giving notice about the ADA requirements, and

(3) Establishing a grievance procedure.

The Coordinator: Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 presented many similar requirements

to those found in the ADA and has been around longer than the ADA. If there was an individual who

had responsibility for carrying out the requirements of Section 504, this individual provided a logical

selection for the duties of ADA Coordinator. In many states, an ADA coordinator has been appointed

as a part-time or in some cases a full-time position. In a few states, an ADA coordinator has only been

appointed within the past two years. The background of these staff members varies greatly. Many of

the staff members in these positions have backgrounds that do not match the technical requirements

that are needed to successfully complete the activities required to comply with ADA. This presents a

roadblock for the agencies at the outset of the process and can lead to delays in compliance.

The Coordinator may report to the Human Resources Department or to a Civil Rights Department.

The direction to the process provided by an ADA coordinator generally correlates with the successful

drafting and implementation of the Transition Plan.

Whether there is a staff of one or an entire ADA task force, training was also cited by various

Departments as an important tool for ensuring compliance with ADA requirements and completion of

ADA Transition Plans. Many Departments have staff that has participated in some form of ADA

training from the Federal Highway Administration, the US Access Board, or other agencies. Several

other Departments are requiring that all personnel within the DOT receive training. Educating

Department staff in the requirements of Title II of the ADA results in better flow of information

regarding non-compliant rights-of-way and can creates a “buy-in” to the process by all staff.

Giving Notice of ADA Requirements: As described above, Departments are required to give notice

to the public on information regarding public accessibility and compliance with ADA. A Department’s

web site is generally the first resource for the public to seek out information about pedestrian

accessibility in the public right-of-way. There are a wide range of approaches to providing website

KEY TO SUCCESS

Providing dedicated, trained staff within the Department for ADA compliance has a high

correlation with successful drafting and implementation of Transition Plans, Self-evaluations,

and Transition Plan updates.

Page 9

information about ADA requirements among the Departments - varying from a webpage devoted

exclusively to the subject, to a link on the main web page, to passive discussion of the issue

submerged in other topics.

By providing this information on-line, the Department widens the accessibility of the information and

allows for education of the general public and facilitates the exchange of information with the disabled

community. Utilizing the Department’s web page can provide a one stop portal for issues related to

ADA compliance, including pedestrian accessibility on Department rights-of-way, Transition Plan

status and methodologies for filing complaints. Many Departments home pages have links to the

“ADA/Accessibility Program”. Other websites mention the ADA only passively as part of other

discussions. More commonly, the ADA is mentioned, but not highlighted, under statewide pedestrian

and bicycle plans, policies, programs, and planning guidance.

The best practice for notification is to provide a clear and exclusive reference to the ADA requirements

on the Department’s webpage in order to best address the notification requirement.

Other forms of notice that Departments utilize include public meetings. Meetings should be targeted

to the pedestrian community and specifically to the disabled pedestrian community. Mailings and

information regarding meetings can be distributed to this targeted community with the help of

advocacy groups for the disabled.

Grievance Procedure: As a regulatory requirement of ADA, the Department must adopt and publish

a grievance procedure providing for prompt and equitable resolution of complaints alleging any action

that would be prohibited under Title II. In addition to the regulatory requirement of including the

grievance procedure in the Transition Plan, it is also good practice to include this detailed information

on the Department’s website. The grievance procedure should make methods clear for any member

KEY TO SUCCESS

Provide a website with links to the various components of the ADA Transition Plan such as

policies, compliance planning for construction and retrofits, opportunities for public

participation, links to the ADA advisory committee, grievance procedures, and the schedule for

implementation of the program.

KEY TO SUCCESS

One state found that public meetings on the newly completed inventory were better attended

when they were coupled with another meeting geared toward the disabled community – such

as linking the meeting with a regularly scheduled meeting of the Statewide or Local

Commission on Disabilities.

Page 10

of the public wishing to inform the Department of potential hindrances to public access along

pedestrian rights-of-way. Exchange of this information is a critical step in addressing potential ADA

noncompliance and preventing the escalation of the grievance to a formal civil complaint.

Department approaches to this responsibility vary from simply adopting the state grievance procedure,

to developing unique approaches for the Department itself.

SELF-EVALUATION PHASE

As the initial step in the Transition Plan, Departments are required to conduct an inventory of their facilities to

determine if they are accessible by persons with disabilities. This stage is often referred to as the self-

evaluation phase. This section discusses how agencies have undertaken or are planning to undertake this

assignment.

The Inventory: Many Departments reported the completion of the inventory during the self-evaluation

as being the biggest and most daunting task of the Transition Plan process. Lack of budget and

(associated) lack of staffing often make this task extremely challenging to complete. Budgetary

constraints as well as management decisions on staffing and support of ADA programs are a major

factor in each Department’s ability to complete the tasks associated with updating the Transition Plan.

As a result, many states report being stalled in the inventory phase, either awaiting the completion of

self-evaluation activities or unable to take the data collected and develop priorities for upgrades.

Ideally, dedicated funding and staffing would be planned out through the completion of the Transition

Plan prior to starting any self-evaluation activities.

Several states have adopted a two pronged approach to Transition Plan development due to the level

of effort required to fully inventory state rights-of-way, by creating two separate plans; one for buildings

and one for rights-of-way. This allows the compliance effort for buildings and other public facilities to

proceed without being held up during completion of state wide inventory of rights-of-way. Other

states have prioritized the inventory and are approaching the task in stages. These Departments have

completed part of the inventory to include highly used areas such as urban areas with high pedestrian

traffic, and areas near facilities that are commonly used by pedestrians with disabilities, such as a

school for the blind. This allows for the Department to move forward with updating the Transition Plan

KEY TO SUCCESS

Making the grievance procedure as straightforward as possible for the public can facilitate

information exchange regarding non-compliant sites, and can help the Department avoid

escalation of grievance issues. By allowing the public to choose any method of filing a

grievance, from writing a formal complaint to the ombudsman, filing a complaint electronically

through the website, contacting any Department business office, or calling a toll free number,

the Department ensures a better exchange of information.

Page 11

to address these high traffic areas, and the Department can then complete the inventory of remaining

rights-of- way as time and resources allow.

Other states have utilized the organization of the Department into regions or districts as a logical way

of dividing the inventory process, with each District responsible for self-evaluation activities and

development of an individual Transition Plan covering their geographic area. Where the inventory

process has been divided up, states continue to maintain a central location of inventory data to allow

for access by the public and other offices within the state.

Inventory also requires an assessment of who is responsible for the facilities’ compliance. Many

states reported that determining who was responsible for compliance was often difficult and can stall

the inventory process, since it is unclear what should be included in the self-evaluation. Sidewalks on

state roads within municipalities were cited as sometimes problematic, as were public transit facilities

that were owned by the DOT but operated by others. Some Departments turn over ownership of

sidewalks to municipalities upon completion of construction. In cases where responsibility for

compliance is in question, it is critical that the municipality and the Department be in close contact to

allow for resolution. Departments have reported grievances being filed with no clear idea of who is

responsible for upgrading the facility, leading to delay in addressing the nonconformity.

Making the Information Available: The most common method of storing the data gathered during

the inventory process is quickly becoming the utilization of GIS. Some states have held outreach

meetings with data displays on which the public can view street level detail of public access issues

along state rights-of-way. GIS enables linking real photos of the site with a general mapping tool and

engineering data. Providing this type of street level information to the members of the public greatly

enhances the readability of the information, and can create a more productive information exchange.

Establishing a Baseline: The main goal of the Self-evaluation phase is to provide a baseline of what

facilities under the Department’s responsibility are noncompliant with ADA standards. Comparisons to

the initial self-evaluation will provide evidence of a Department’s good faith in efforts to comply with

ADA requirements.

KEY TO SUCCESS

When staffing or funding for inventory efforts is a challenge, many Departments get creative –

several states have reported using summer interns for self-evaluation activities on public rights

–of-way. Others prioritize the inventory process by looking at high pedestrian areas first. In

this way, even if a complete inventory cannot be undertaken, those areas that will be most

utilized (such as urban intersections) are addressed.

Page 12

IMPLEMENTATION

When the self-evaluation is completed and the Department has an inventory of where structural modifications

are required to achieve accessibility, the Department must plan for the removal of these barriers. A Transition

Plan must contain at a minimum:

(1) a list of the physical barriers that limit the accessibility of services to individuals with disabilities (the

inventory),

(2) a detailed outline of the methods to be used to remove these barriers and make the facilities

accessible,

(3) a schedule for taking the necessary steps to achieve compliance, and

(4) the name of the official responsible for the plan’s implementation.

Curb Ramp Deficiencies: Curb Ramps are a small but vitally important part of making sidewalks,

street crossings, and the other pedestrian routes that make the public right-of-way accessible to

people with disabilities. They receive special consideration in the Transition Plan with a separate

schedule for the remediation of curb ramp issues. The primary issue with curb ramps in many

Departments is how to proceed with rectifying a large, long term problem in a logical manner.

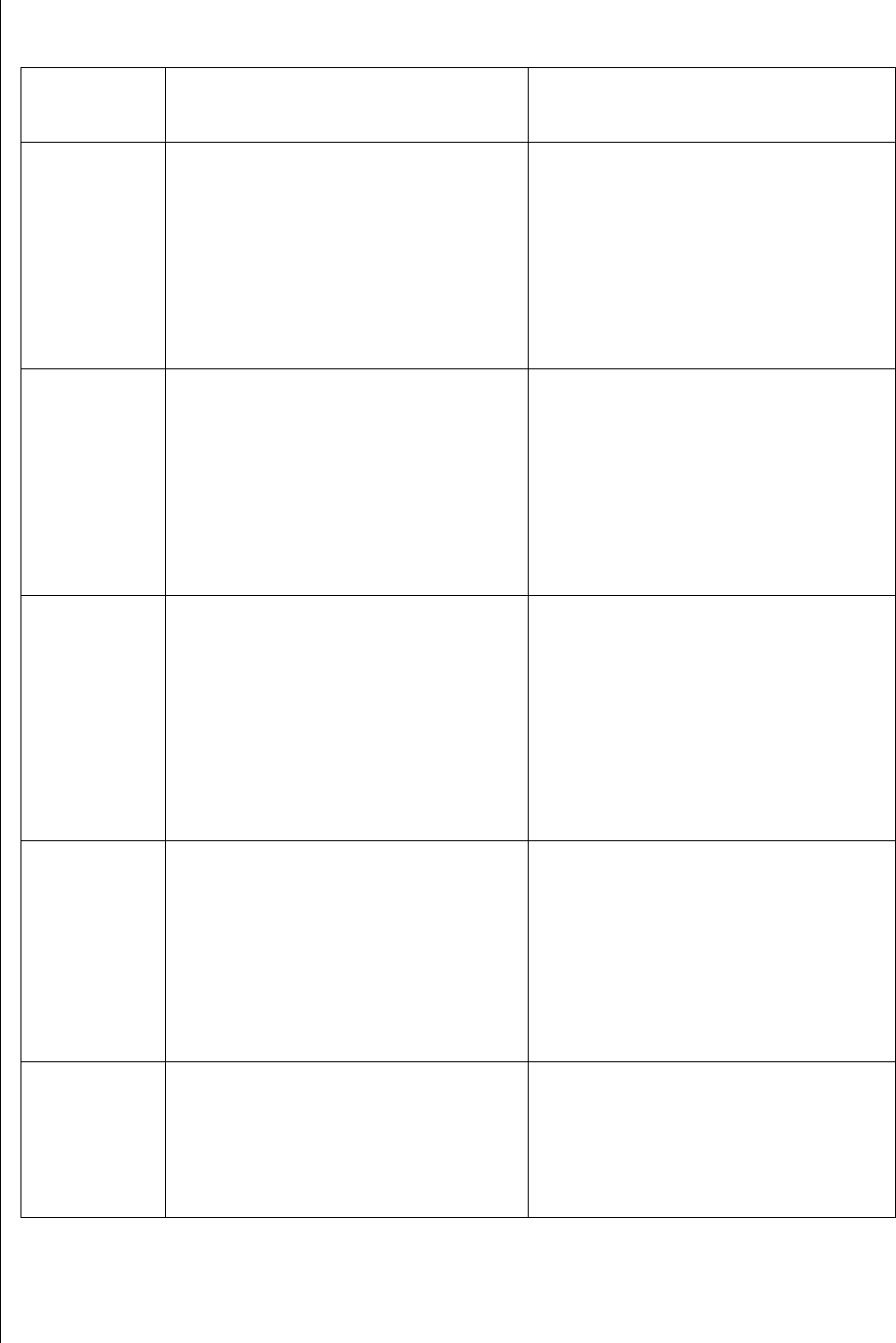

The following table provides an example from one Department of how to prioritize removal of accessibility

barriers. The Table uses a ranking system (priority) based on variables (Situation) that include location,

degree of utilization and degree of non compliance.

KEY TO SUCCESS

A very detailed approach for setting priorities for dealing with curb ramps (or other non

conformities) can help with successful implementation of the Plan. Criteria can include both

physical characteristics and location considerations. Making use of such a specific criteria

presupposes that sufficient detail has been gathered in the self-evaluation phase so that the

curb ramps can be accurately characterized.

Page 13

PRIORITY

SITUATION

Highest

1A

Existing Curb Ramp with Running Slope Greater than 12% and Location

near a Hospital, School, Transit Stop, Government Building, or Similar

Facility

1B

No Curb Ramp where Sidewalk or Pedestrian Path Exists and Location

near a Hospital, School, Transit Stop, Government Building, or Similar

Facility

2A

An Existing Curb Ramp with a Running Slope Greater than 12% (Not

Located near a Hospital or Similar Facility)

2B

No curb ramp where a Sidewalk or Pedestrian Path Exists (Not Located

near a Hospital or Similar Facility)

3

No Curb Ramp where a Striped Crosswalk exists

4

One Curb Ramp per Corner and Another is Needed to Serve the Other

Crossing Direction

5A

An Existing Curb Ramp with either a Running Slope Greater than 1 to 12

or an Insufficient Landing

5B

An Existing Curb Ramp with Obstructions in the Ramp or the Landing

5C

An Existing Curb Ramp with any of the Following Conditions:

o A Cross Slope Greater than 3%

o A Width Less Than 36 Inches

o No Flush Transition or a Median or Island Crossings that are

Inaccessible

5D

An Existing Curb Ramp with Returned Curbs where Pedestrian Travel

Across the Curb is not Permitted

5E

An Existing Diagonal Curb Ramp without the 48 Inch Extension in the

Crosswalk

5F

An Existing Curb Ramp without Truncated Dome Texture Contrast or

without Color Contrast

Lowest

The Pedestrian Push Button is not Accessible from the Sidewalk or from

the Ramp

Page 14

Schedule: Setting priorities for the implementation of upgrades is a requirement. Transition Plans

should include a year by year schedule of upgrades. Many Departments will prioritize projects based

on level of anticipated use rather than the degree of non-compliance. Curb ramps or intersections that

may be near facilities for the disabled, are generally given priority for upgrade. However, oftentimes it

is difficult for Departments to know themselves which intersections are most utilized by persons with

disabilities.

Funding: The funding for implementation of the Transition Plan can come from several sources, as

discussed earlier in this report and in the FHWA guidance found at

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/civilrights/ada_qa.htm#q30. Lack of funding and staffing were cited as the

most common roadblocks to completing the inventory and the Transition Plan. In Departments where

dedicated funding and staffing is not in place, Transition Plans are generally not completed. In the

longer term, this may lead to civil suits and expensive litigation for Departments. Establishing a well

developed Transition Plan can be viewed as a capital planning tool and will allow for better

Departmental control over the compliance process.

The funding of the upgrades found in the Transition Plan is also a consideration, since ADA

compliance activities do not stop with the successful completion of the Transition Plan, or the update

of a Transition Plan. The improvements therein must be funded and undertaken as well. Accessibility

improvements are generally incorporated into existing improvement projects. In some cases

Departments have provided special projects that specifically address pedestrian access requirements.

KEY TO SUCCESS

Working closely with advocacy groups to set the schedule for implementation and prioritization

can be extremely beneficial. These groups can help bring information from the public to the

Departments so that money can be best spent on those areas that will serve to benefit the

most people.

KEY TO SUCCESS

One state’s approach to prioritization uses a GIS database that contains information regarding

compliant and non-compliant elements. This GIS information is then displayed along with

locations of pedestrian incidents, feedback from the community or local jurisdiction, locations of

government facilities, locations of public facilities and mass transit stops. Each of these

elements were assigned a value and ranked for priority.

Page 15

Lines of Responsibility: A management structure for the implementation of the Transition Plan is

extremely important in order to fully complete all tasks that are associated with the Plan.

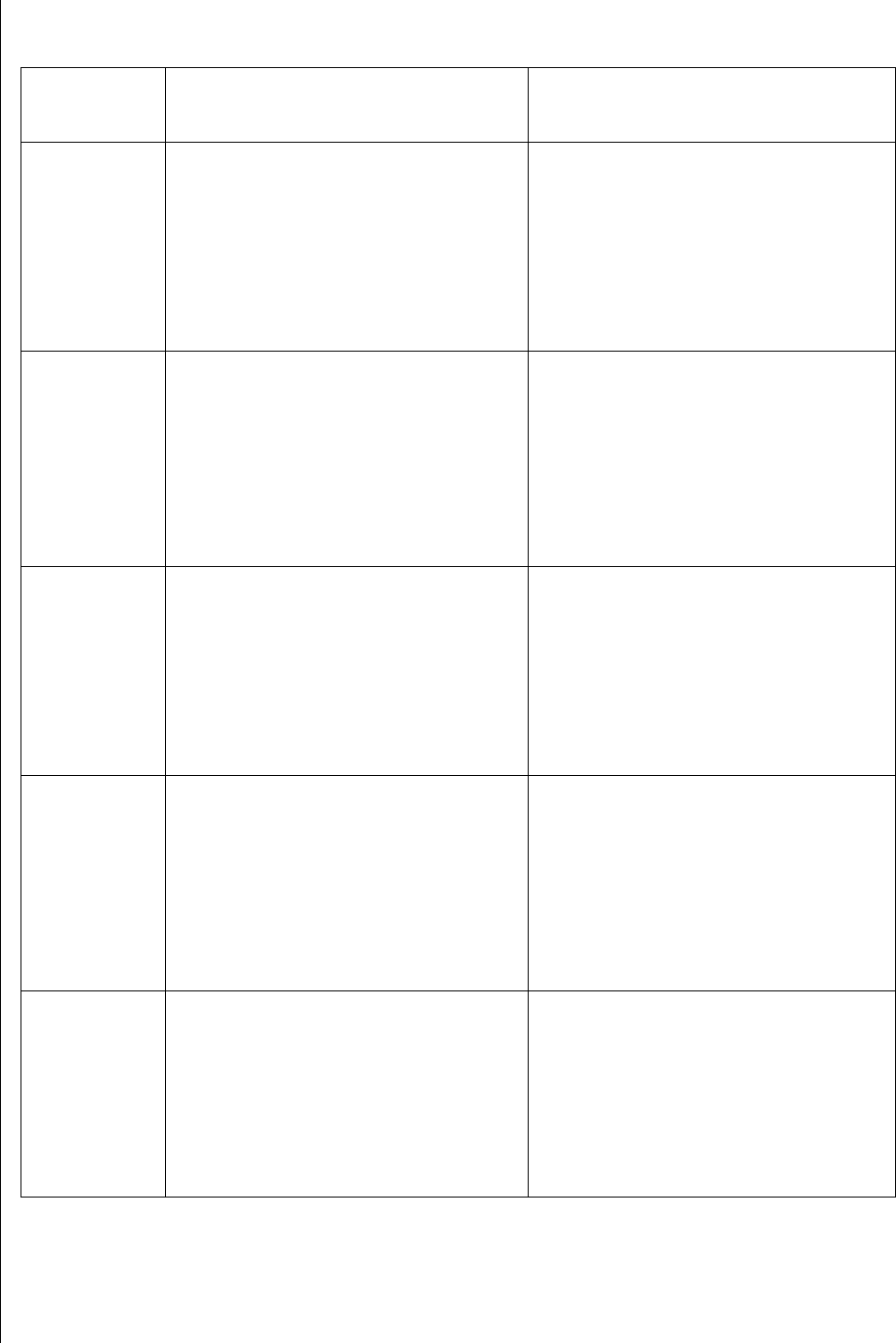

SAMPLE TRANSITION PLAN OUTLINE

Among the states that have not yet completed a Transition Plan, staff members asked if a generic Transition

Plan format is available. In many regions, FHWA provides a sample plan to help Departments facilitate the

process. Although there are mandates for content, there are no requirements for format of the Transition Plan.

KEY TO SUCCESS

Length and level of detail of Transition Plans varies greatly among the states. For example,

one state provides a succinct one and a half page of narrative on rights-of-way and the

prioritization criteria, incorporating the inventory by reference. Other states have a Transition

Plan that provides pages and pages of actual inventory with priorities and proposals for each

individual site. At the outset of the process, a Department should make a determination as to

what level of detail will be included in the Plan and the content that will be the most beneficial

to them in implementing ADA

KEY TO SUCCESS

Beyond simply designating an ADA Coordinator, many Departments have a designated

Transition Plan manger, as well. While the ADA Coordinator may be involved in public

outreach and oversight of ADA compliance, the Transition Plan manager may be better

equipped to handle the technical aspects related to the self-evaluation activities and Transition

Plan updates.

Page 16

The following is a sample of one possible outline for Transition Plans.

SECTION

CONTENTS

I SELF-EVALUATION :

A list of physical barriers in the department’s facilities that limit

accessibility of individuals with disabilities. This may take the form

of an Excel spreadsheet or GIS files incorporated by reference,

or can be worked into a narrative list to be embedded in the text

of the Transition Plan.

II CORRECTION PROGRAM:

A detailed description of the methods to remove these barriers

and make the facilities accessible.

III IMPLEMENTATION SCHEDULE:

A schedule for taking the necessary steps.

IV PROGRAM RESPONSIBIL ITY:

The name of the official responsible for implementation. This

should include the name of the department ADA coordinator, as

well as a transition plan team (if there is one), or the regional

coordinators, if the inventory and transition plans area is divided

by region or district.

V CURB RAMP CORRECTION PROGRAM:

A schedule for providing curb ramps.

VI PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT RECORD:

Record of the opportunity given to the disability community and

other interested parties to participate in the development of the

Plan.

ATTACHMENTS

PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT

The Department is required to provide an opportunity for people outside of the agency, people with disabilities,

and other interested individuals and organizations to review and comment on the Transition Plan. This section

presents some of the approaches agencies have used to provide this opportunity.

The Dissemination of Information: Although all Departments now have websites, very few have the

Transition Plan available for public review. This represents a missed opportunity as an avenue for

information dissemination. In addition to providing information for the public at large, the targeted

distribution of information should also be undertaken. Advisory groups that may have worked with the

Department during the development of the Plan and the prioritization of the upgrades would receive

the information. Advocacy groups that work with the disabled community, as well as any individuals

with disabilities that may have participated in Plan development in some way (ex. through grievance

filings, through hotlines or through previous public meetings), would also be interested in reviewing the

plan.

Page 17

COORDINATION WITH OTHER AGENCIES

Coordination among transit agencies can be a helpful step in creating a Transition Plan that is concise and

effective in addressing upgrades.

Public Transit: There are many states where Departments are not only responsible for pedestrian

access along public rights-of-way but also for pedestrian access to other transit facilities.

Departments of Transportation also frequently have responsibility for public transit such as

responsibility for airports, ferry systems, light rail systems and bus terminals. Each of these presents

unique compliance issues. All facilities need to be included in the Department’s Transition Plan.

KEY TO SUCCESS

Seeking the involvement of Advocacy groups and the disabled public early in the process can

lead to better success in dealing with non-compliance areas. This early coordination can

provide valuable information to the Department from people who most use the pedestrian

facilities and provides and opportunity for the concerns that are most important to the advocacy

groups and the public to be addressed more effectively. These groups know best where

problem areas are and their input can provide valuable insight to Departments that are trying to

set priorities for upgrades.

KEY TO SUCCESS

Creation of a regional working group for ADA compliance issues was cited by several states in

the east as being a helpful practice in completing tasks related to the Transition Plan. These

interstate groups are made up of an ADA coordinator as well as other members of

Departments and FHWA. The meetings provide a forum for exchange of ideas and any Best

Management practices. The groups exchange ideas in their approach to developing inventories

and updating Transition Plans. Regional grouping also enables common challenges among

the states to be more effectively addressed. Densely urbanized areas in the Northeast, with

miles of urban sidewalks interspersed with public transit have different pedestrian issues than

newer cities in the Southwest. For example, Washington State deals with an entirely different

pedestrian issue in managing the nations’ largest ferry system. Creating regional work groups

can facilitate discussion of common regional problems.

Page 18

Adjacent Jurisdictions: Where facilities owned and operated by the Department abut facilities owned

by others, such as a municipality, responsibility for ADA compliance should be coordinated. For

example group meetings with ADA coordinators throughout the state have been cited by some states

as valuable in avoiding conflict among adjacent jurisdictions. In one phone interview with a

Department ADA Coordinator, the coordinator explained that one of his priorities for the upcoming

year was to create a master list for the state of all ADA Coordinators at the municipal and state level to

facilitate statewide interagency coordination. Taking this one step further, many Departments in the

northeast participate in a civil rights working group among the states. This group addresses Title II

compliance as one of its tasks

IV CONCLUSION

The purpose of this document is to ensure that good ideas, helpful information, and successful practices

concerning the development and updating of Program Access Plans or Transition Plans are recognized,

recorded, and shared among Departments of Transportation.

The ideal conclusion to this process is the elimination of the barriers and the acceptance of the requirements

of the ADA as an everyday reality in all future work going forward. Due to the magnitude of the task and the

other priorities that a Department faces, the ideal scenario has not universally played out. Although the

majority of Departments contacted had some form of inventory or Transition Plan completed, many of the

Departments reported that they were either just beginning the process or didn’t have firm plans for preparing a

Transition Plan.

By highlighting some of the issues and the methods used to address issues that the Departments face when

developing and updating their ADA Transition Plans it is desired that going forward all Departments can make

significant progress towards improving access to the facilities they manage. This document presents ideal

scenarios and some of the best practices of Departments across the country. It is recognized that each

Department or responsible agency will have to tailor an approach to developing, updating and implementing a

Transition Plan based upon their own needs and available resources and that the level of detail and content of

the Plan will vary and be presented in a format that will be the most beneficial to them in implementing ADA.

V FURTHER REFERENCE

There are many guidance documents available on the internet with helpful information to assist in completing

and updating ADA Transition Plans. Some of those more frequently cited by Departments include the

following:

FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION OFFICE OF CIVIL RIGHTS QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS ABOUT ADA AND

SECTION 504, January 2008. Available, [ retrieved December 2008]

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/civilrights/ada_qa.htm

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE ADA BEST PRACTICES TOOLKIT FOR STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS June

2008. Available, [retrieved December 2008] http://www.ada.gov/pcatoolkit/toolkitmain.htm .

UNITED STATE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, THE AMERICANS WITH DISABILITIES ACT, TITLE II TECHNICAL

ASSISTANCE MANUAL, COVERING STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT PROGRAMS AND SERVICES, November

1993. Available, [ retreived December 2008] http://www.ada.gov/taman2.html

Page 19

PUBLIC RIGHTS-OF-WAY ACCESS ADVISORY COMMITTEE and ITE Publication Special Report: ACCESSIBLE

PUBLIC RIGHTS-OF-WAY, PLANNING AND DESIGNING FOR ALTERNATIONS. Available, [ retreived December

2008 ] http://access-board.gov/prowac/alterations/guide.htm

US ACCESS BOARD, REVISED GUIDELINES FOR ACCESSIBLE PUBLIC RIGHTS-OF-WAY. November 2005.

Available, [ retreived December 2008] http://www.access-board.gov/PROWAC/draft.htm

FHWA DESIGNING SIDEWALKS AND TRAILS FOR ACCESS PART 2. Available, [ retreived December 2008]

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/sidewalk2 .

KRW INCORPORATED, ADA TRANSPORTATION ACCESSIBILITY REFERENCE GUIDE, Project Action, National

Easter Seal Society, and U.S. Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board, March 1993.

Many Departments cited recent training from FHWA as being helpful in understanding the issues surrounding

ADA Transition Plan compliance. The FHWA training documents are often used as reference documents

during the updating of a Transition Plan.

Statutes and Regulations: The Department’s Title II regulations for state and local governments are found at

Title 28, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 35 (abbreviated as 28 CFR pt. 35. The ADA Standards for

Accessible Design are located in Appendix A of Title 28, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 36 (abbreviated as

28 CFR pt. 36 app. A). Those regulations, the statute, and many helpful technical assistance documents are

located on the ADA internet Home Page at http://www.ada.gov and on the ADA technical assistance CD-ROM

available without cost from the toll-free ADA Information Line at 1-800-514-0301 (voice) and 1-800-514-0383

(TTY).

VI ATTACHMENTS

LIST OF ADA CONTACTS BY STATE

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

Alabama

Byron Browning

Assistant ADA Coordinator

Alabama Department of Transportation

1409 Coliseum Boulevard

Montgomery, AL 36110

334-242-6942

Page 20

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

Alaska

Jon Dunham

Civil Rights Office Manager

2200 East 42nd Avenue

PO Box 196900

Anchorage AK 99519-6900

907-269-0851

[email protected]ate.ak.us

Arizona

Edward Edison

Civil Rights Administrator

Arizona Department of Transportation

1135 N 22nd Ave, 2nd Floor

Phoenix, AZ 85009

602-712-7761

Arkansas

James Moore

Internal EEO Coordinator

Arkansas State Highway &

Transportation Department

10324 Interstate 30

Little Rock, Arkansas 72209

501-569-2299

james.moore@arkansashighways.com

California

Alex Morales III

ADA/504 Coordinator

California Department of Transportation

Civil Rights Program

1823 14th Street

MS 79

Sacramento CA 95814

916-324-8764

.

Jerry Champa is the lead for the

Transition Plan effort

California Department of Transportation

Civil Rights Program

1823 14th Street

MS 79

Sacramento CA 95814

916-324-8764

jerry_cham[email protected]]

Page 21

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

Colorado

Benjamin Cordova

ADA Coordinator

Colorado Department of Transportation

Center for Equal Opportunity

4201 East Arkansas Avenue, Room 200

Denver, Colorado 80222

303-757-9594

benjamin.cordova@dot.state.co.us

Connecticut

John F. Carey

Transportation Division Chief

Connecticut Department of

Transportation

2800 Berlin Turnpike

P.O. Box 317546

Newington, CT 06131-7546

860-594-2710

Delaware

Linda M. Osiecki, M.E., P.E.

Program Manager, Quality Section

Delaware Department of Transportation

800 Bay Road

P.O. Box 778

Dover, DE 19903

302-760-2342

District of

Columbia

Brett Rouiller

ADA/504 Coordinator

District of Columbia Department of

Transportation

2000 14th Street, NW

5th Floor

Washington, DC 20009

202-497- 4722

Page 22

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

Florida

Dean Perkins

ADA Coordinator

Florida Department of Transportation

Haydon Burns Building

605 Suwannee Street

Tallahassee, Florida 32399-0450

850-414-4359

[email protected].fl.us

Georgia

Ulander Gervais

Title VI/Environmental Justice Specialist

Georgia Department of Transportation

Office of Equal Opportunity

2 Capitol Square

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

404-463-6928

[email protected]ate.ga.us

Hawaii

Benjamin Gorospe

ADA Coordinator

Hawaii Department of Transportation

Office of Civil Rights

869 Punchbowl Street #112

Honolulu, Hawaii 96813

808-587-7584

benjamingGorospe@hawaii.gov

Idaho

Karen Sparkman

Director, Civil Rights Section

Idaho Transportation Department

P. O. Box 7129

Boise, ID 83707-1129

208-334-8852

karen.sparkm[email protected]

Page 23

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

Illinois

David Dailey

ADA Specialist

Bureau of Civil Rights

2300 South Dirksen Parkway, Room 317

Springfield, IL 62764

217-557-5900

Indiana

Christine D. Cde Baca

Title VI/ADA Administrator

100 North Senate, Room N750

Indianapolis, IN 46204

317-234-6142

Iowa

Roger E. Bierbaum

Director, Office of Contracts

Highway Division

Iowa Department of Transportation

800 Lincoln Way

Ames, IA 50010

515-239-1414

roger.bierbaum@dot.iowa.gov

Kansas

Mike Smith

Internal Civil Rights/ADA Coordinator

Kansas Department of Transportation

Eisenhower State Office Building

700 SW Harrison

Topeka, Kansas 66603

785-296-2279

eeooffice@ksdot.org

Kentucky

Kathy Marshall

Office of Human Resources

Kentucky Transportation Cabinet

200 Mero Street

Frankfort, KY 40601

502-564-4610

KathyN.Marshall@ky.gov

Page 24

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

Louisiana

Candy Cardwell

Human Resources Analyst

Human Resources Section

Louisiana Department of Transportation

and Development

P.O. Box 94245

Baton Rouge, LA 70804-9245

225-379-1241

candycardwell@dotd.louisiana.gov

Maine

GiGi Ottmann-Deeves

Maine Department of Transportation

16 State House Station

Augusta, ME 04333

207-624-3036

gigi.ottmann-[email protected]v

Maryland

Linda I. Singer

ADA Title II Coordinator, Legislative

Manager

Office of Policy and Research

Maryland State Highway Administration

707 North Calvert Street

Baltimore MD 21202

410-545-0362

Massachusetts

David Phaneuf

ADA Coordinator

Massachusetts Highway Department

State Transportation Building

10 Park Plaza, Room 3170

Boston, MA 02116

617-973-7722

Angela Rootekoff

Office of Civil Rights

State Transportation Building

10 Park Plaza, Room 3170

Boston, MA 02116

617-973-7025

angela.rootekof[email protected]a.us

Michigan

Tony Kratofil

Bay Region Engineer

55 E. Morley Dr.

Saginaw, MI 48601

989-754-0878

Page 25

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

Minnesota

Bruce Latu

Minnesota Department of Transportation

395 John Ireland Boulevard

St. Paul, MN 55155-1899

651-291-1016

Mississippi

Carolyn Bell

Civil Rights Manager

Mississippi Department of Transportation

401 North West Street

Jackson, MS 39201

601-359-7466

Missouri

Lester Woods

External Civil Rights Administrator

Missouri Department of Transportation

1617 Missouri Boulevard

Jefferson City, MO 65109

573-751-2859

lester.woodsJr@modot.mo.gov

Stefan Denson

Missouri Department of Transportation

1617 Missouri Boulevard

Jefferson City, MO 65109

573-751-1355

stefan.denson@modot.mo.gov

Montana

Alice Flesch, Program Manager

Montana Department of Transportation

2701 Prospect Avenue

PO Box 201001

Helena, MT 59620-1001

406-444-9229

aflesch@mt.gov

Nebraska

Jim Knott

Director, Roadway Design Division

Nebraska Department of Roads

Roadway Design

1500 Highway 2

PO Box 94759

Lincoln, NE 68509-4759

402-479-4601

Page 26

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

Nevada

Dennis Coyle

ADA/504 Coordinator

Nevada Department of Transportation

1263 South Stewart Street

Carson City, NV 89712

775-888-7598

New

Hampshire

David Chandler

New Hampshire Department of

Transportation

7 Hazen Drive

P.O. Box 483

Concord, NH 03302-0483

603-271-2467

[email protected].nh.us

New Jersey

Chrystal Section-Williams

Title VI Analyst

Division of Civil Rights & Affirmative

Action

New Jersey Department of

Transportation

1035 Parkway Avenue

Trenton, NJ 08618

609-530-2939

chrystal.section-williams@dot.state.nj.us

Paul Thomas

ADA Transition Plan Manager

New Jersey Department of Transportation

1035 Parkway Avenue

Trenton, NJ 08618

paul.thom[email protected]

New Mexico

Jose Ortiz

ADA Coordinator

New Mexico State Transportation

Department

Aspen Plaza1596 Pacheco Street

Santa Fe, NM 87505

505-827-1648

jose.o[email protected].us

Page 27

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

New York

David Perez

Compliance Specialist II

New York State Department of

Transportation

Office of Audits and Risk Management

Services

Civil Rights Bureau, Pod 62

50 Wolf Road

Albany, New York 12232

North Carolina

Walt Thompson

Director, Productivity Services

North Carolina Department of

Transportation

1517 Mail Service Center

Raleigh, NC 27699-1517

919-733-2083

[email protected].nc.us

North Dakota

Mark S. Gaydos, P.E.

North Dakota Department of

Transportation

Design Division

608 East Boulevard Avenue

Bismarck, ND 58505-0700

701-328-4417

mgaydos@nd.gov

Roger Weigel

North Dakota Department of

Transportation

Design Division

608 East Boulevard Avenue

Bismarck, ND 58505-0700

701-328-4403

Ohio

Kimberly Watson

EEO Program Administrator

Office of Chief Legal Counsel

Civil Rights Unit

Ohio Department of Transportation

Central Office

1980 West Broad Street

Columbus, OH 43223

614-728-9245

[email protected]ate.oh.us

Page 28

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

Oklahoma

Glenn Brooks

Title VI Coordinator

Oklahoma Department of Transportation

200 N. E. 21st Street, Room 1-B4

Oklahoma City, OK 73105

405-521-4139

[email protected]ladot.state.ok.us.

Oregon

Martha Smith

EEO/Affirmative Action/ADA Coordinator

Oregon Department of Transportation

Office of Civil Rights/Human Resources

104 Transportation Building

355 Capitol Street NE

Salem, OR 97301

503-373-7093

martha.sm[email protected]

Pennsylvania

Chris Drda

Chief, Consultant Agreement Section

Bureau of Design

Pennsylvania Department of

Transportation

400 North Street

Keystone Building, 7th Floor

Harrisburg, PA 17120

717-783-9309

Puerto Rico

Ana Olivencia

ao[email protected]p.gov.pt

Page 29

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

Rhode Island

Michael Penn

Senior Civil Engineer

Rhode Island Department of

Transportation

Two Capitol Hill

Providence, RI 02903

401-222-2023 x4050

South Carolina

Natalie Moore

ADA Coordinator

South Carolina Department of

Transportation

955 Park Street

Columbia, SC 29201

803-737-1347

adacoordinator@scdot.org

South Dakota

June Hansen

Civil Rights Compliance Officer

South Dakota Department of

Transportation

700 East Broadway Avenue

Pierre, SD 57501

605-773-3540

june.hansen@state.sd.us

Tennessee

Margaret Mahler

ADA Coordinator

Tennessee Department of Transportation

Suite 400 – James K. Polk Building

505 Deaderick Street

Nashville, TN 37243

615-741-4984

margaret.z.m[email protected]

Texas

Jesse W. Ball Jr.

Civil Rights Director

Texas Department of Transportation

Office of Civil Rights

125 East 11th Street

Austin, TX 78701-2483

512-475-3117

Page 30

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

Utah

Warren Grames

Risk Manager

Utah Department of Transportation

4501 South 2700 West

4th Floor

Salt Lake City, UT 84114-8430

801-965-4272

Ming Jiang

Pedestrian Safety Engineer

Utah Department of Transportation

4501 South 2700 West

4th Floor

Salt Lake City, UT 84114-8430

801-965-4427

Vermont

Lori Valburn

Director of Civil Rights Programs

Vermont Agency of Transportation

National Life Building - Drawer 33

Montpelier, VT 05633

802-828-5561

lori.valburn@state.vt.us

Virginia

Alexis Thornton-Crump

SPHR, Certified Mediator

Assistant Division Administrator

Civil Rights Division

Virginia Department of Transportation

1401 East Broad Street,

Richmond, VA 23219

804-786-4414

[email protected]ginia.gov

Freddie Jones

Virginia Department of Transportation

1401 East Broad Street,

Richmond, VA 23219

804-786-4552

[email protected]irginia.gov

Washington

Kathryn LePome

ADA Coordinator

Washington State Department of

Transportation

Office of Equal Opportunity

P.O. Box 47314

Olympia, WA 98504

360-705-7097

lepomek@wsdot.wa.gov

Page 31

State

ADA Coordinator

Contact

(if different than ADA coordinator)

West Virginia

Ray Lewis, P.E.

Traffic Research and Special Projects

Engineer

West Virginia Division of Highways

Traffic Engineering

Division1900

Kanawha Boulevard East,

Building Five

Charleston, WV 25305

304-558-3063

Wisconsin

Title VI Coordinator

Civil Rights and Compliance Section

Bureau of Equity and Environmental

Services

Wisconsin Department of Transportation

4802 Sheboygan Avenue, Room 451

Madison, WI 53705

608-266-0208

[email protected].wi.us

Michele Carter and Ronald Ulvog

Facilities Maintenance Personnel

4802 Sheboygan Avenue, Room 451

Madison, WI 53705

608-266-0208

608-266-5359

michele.carter@dot.state.wi.us

ronald.ulvog@dot.dtate.wi.us

Wyoming

Lonny Pfau

Human Resources Manager

Wyoming Department of Transportation

5300 Bishop Boulevard

Cheyenne, WY 82009

307-777-4103

[email protected]te.wy.us

Kent Lambert

Wyoming Department of Transportation

5300 Bishop Boulevard

Cheyenne, WY 82009

kent.lam[email protected]y.us

Page 32

QUESTIONNAIRE

QUESTIONNAIRE FOR DEPARTMENTS OF TRANSPORTATION

DEVELOPMENT OF A BEST PRACTICES GUIDE

TO UPDATE ADA TRANSITION PLANS

NCHRP PROJECT NUMBER 20-7 (232)

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and other federal statutes place responsibility

on state departments of transportation to meet accessibility requirements for

pedestrians. These requirements include a self-evaluation study to see where the

agency’s facilities stand with regard to accessibility and a transition plan to provide the

needed accessibility improvements. An interview process with state departments of

transportation is being carried out as part of a study called “Development of a Best

Practices Guide to Update ADA Transition Plans”. The study is being sponsored by the

National Cooperative Highway Research Program; Jacobs Edwards and Kelcey is under

contract to conduct interviews and prepare a report. The overall goal of the study is to

ensure that good information, good ideas, and good practices concerning transition

plans for pedestrian accessibility programs are recognized, recorded, and shared.

There are three parts to the questionnaire: (1) the determination of some background

information, (2) a discussion of self-evaluation studies that are used to define needed

accessibility improvements, and (3) a discussion of transition plans that are used to carry

out the improvements needed to bring facilities in line with accessibility standards.

Agency

Contact Person

Title

Telephone Number

E-Mail Address

Date of Discussion

What are your responsibilities?

ADA Coordinator?

Title II Coordinator?

Section 504 Coordinator?

Page 33

Self-Evaluation Plan Manager?

ADA Transition Plan Manager?

Other?

I BACKGROUND

Agencies vary greatly in their responsibilities and their structure and in the nature of the

facilities that they manage. This section is intended to provide some context to help

understand agency planning for accessibility.

1. Agency Responsibilities

The goal of this section is to determine the range of resources that the agency is

responsible for. This range can vary widely between agencies. This study concerns

itself only with highway rights-of-ways but the overall context of the agency’s

responsibilities needs to be understood.

What types of resources is your agency

responsible for?

Highways?

Rest Areas?

Welcome Areas?

Scenic Overlooks?

Recreation Areas?

Office Buildings?

Maintenance Facilities?

Bus Transit Systems?

Bus Stops?

Van Transit Systems?

Rail Transit systems

Public Safety Facilities?

Page 34

Railways?

Ferries?

Airports?

Ports and Harbors?

Pipelines?

Waterways?

Anything else?

2. The ADA Compliance Role Within the Agency

Transportation Agencies vary widely in how they integrate the ADA compliance

responsibility into their organization. The goal of this section is to understand how the

agency assigns the responsibility for ADA compliance.

Where does the ADA Coordinator role fall

within your Agency?

Office of the Commissioner?

Civil Rights Office?

Legal Department?

Public Affairs Department?

Pubic Involvement Department?

Programs Department?

Planning Department?

Design Department?

Right-of-way Department?

Maintenance Department?

Other?

Page 35

3. Document Development

Agencies vary in their progress on formal document development. The goal of this

section is to determine where the agency stands in this process.

Does your agency have a joint self-

evaluation and transition plan?

Where can it be seen?

Is it updated periodically?

Does you agency have a separate self-

evaluation plan?

Does you agency have a separate

transition plan?

Are either of these documents in progress?

4. Compliance Complaints and Suits

The demand for pedestrian accessibility varies based on the nature of the area served.

The goal of this section to understand the nature of the demand for pedestrian

accessibility improvements.

Do you receive complaints about

pedestrian accessibility?

How many?

What are the usual subjects of complaints?

Have you been sued?

Have you entered into any settlements?

Is there an activist community or

organization that focuses on this subject?

Page 36

II SELF-EVALUATION PLAN

The State Department of Transportation is required to conduct a self-evaluation of its

facilities to determine if these facilities are accessible to persons with disabilities. This

can be a massive undertaking. This section is a discussion about how agencies have

undertaken or are planning to undertake this assignment.

1. Inventory of Facilities

The goal of this section is to determine the approach the agency has taken to perform

inventory work.

What is the magnitude of the inventory

challenge?

Roadway miles?

Person hours?

Crew hours?

Months of duration?

What is your initial information base?

Aerial Photography Library?

Map Library?

Drawings?

Field Survey?

Computer Database?

What is your approach to doing inventory

work?

Windshield survey?

On ground survey?

Photo studies?

What is the extent of inventory work?

All pedestrian facilities?

Page 37

Only pedestrian facilities deemed of

concern by the agency?

Only pedestrian facilities in key areas?

Only pedestrian facilities that support a

public service function?

Only pedestrian facilities where complaints

have been received or concerns have

been raised?

Other selection criteria?

What inventory tools have you found

useful?

GPS?

Photography?

GIS Mapping?

Computer Database?

2. Identification of Deficiencies

The goal of this section is to discuss what facilities the agency is typically dealing with

and what some of the common deficiencies are.

What types of facilities are you dealing

with?

Sidewalks?

Curb Ramps?

Curb Cuts?

Driveway Crossings?

Crosswalks?

Ramps?

Medians?

Bus Stops?

Page 38

Bike Paths?

Other?

What types of deficiency issues are you

finding?

Clear Width and Other Dimensions?

(Narrow, Below Guidelines)

Grade?

(Steepness, Angle Points)

Cross Slope?

(Steepness, Irregularity, Variability)

Materials and Finishes?

(Deterioration, Inappropriateness)

Discontinuities?

(Missing Sections, Gaps, Drops)

Obstructions?

(Signs, Lights, Mail Boxes, Fire Hydrants,

Newspaper Boxes, Drainage Structures,

Standing Water)

Detectable Warning Systems?

(Missing, Inappropriate Materials,

Inadequate Size, Wrong Location)

Traffic Signal Systems?

(Inadequate Time Allowed, Inaccessible

Buttons, Inoperable Buttons, Lack of

Visually Impaired Provisions)

Lighting?

(Missing, Not Operating, Inadequate

Levels)

Maintenance and Services?

(Snow Removal, Debris Clean Up, Trash

Cans, Recyclable Material Bins)

Access Through Work Zones?

Other?

Page 39

3. Validation of Selections

The agency is required to provide an opportunity for people with disabilities and other

interested individuals and organizations to review and comment on the self-evaluation of

facilities. The goal of this section is to determine the approaches used to provide this

opportunity.

Is there an Advisory Group?

How do they function?

Periodic meetings?

Field visits?

Other?

Is there input from activists or

organizations?

Is there input from other agencies?

Is there input from elected officials?

Is there a Community Outreach Effort?

Are there local public meetings about

inventory results?

Are these independent meetings or

piggybacked on other community

meetings?