Teens

and

Speeding

Breaking the

Deadly Cycle

PAGE 2 of 27

Acknowledgments

Richard Retting, Sam Schwartz Consulting, researched and wrote the report in consultation with

Pam Shadel Fischer, GHSA Senior Director of External Engagement.

Russ Martin, GHSA Senior Director of Policy and Government Relations, and Kerry Chausmer,

GHSA Director of Programs and Member Services, edited the report. Jonathan Adkins, GHSA

Executive Director, oversaw the report.

Creative by Brad Amburn. This report is made possible with support from Ford Motor Company Fund.

Published January 2021

This publication is primarily directed to Governors Highway Safety Association (GHSA) members,

the state and territorial Highway Safety Ofces (SHSOs) tasked with addressing the behavioral

safety issues that plague the nation’s roadways and contribute to the vast majority of trafc

crashes. It is not intended to be inclusive of all policies or programs, nor does inclusion of a policy or

program imply endorsement by GHSA or Ford Motor Company Fund. Rather it is intended to foster

discussion and action that advances the safety of all roadway users. While SHSOs are the primary

audience, teen driving program providers and advocates, educators, elected ofcials and others

working to advance highway safety will also nd it instructive.

Contents

Executive Summary ............................................3

Introduction ..................................................................4

Size and Nature of the Problem .............. 6

Speeding-related Fatal Crashes

Among Teen Drivers

.......................................... 6

Why the Problem Exists

................................ 11

Developmental Issues

....................................11

Driver Skills and Driving Behavior

........ 11

Reducing the Problem......................................11

Speed Limits and

Speed Enforcement

........................................12

Driver Education and Training

................12

Graduated Driver Licensing

......................14

Parents’ Role ............................................................ 15

In-vehicle Driver Monitoring

.................... 15

Smartphone Apps

.............................................16

In-Vehicle Safety Technology

.................17

Parental Involvement in the

Learning-To-Drive-Process

....................... 18

Modeling Safe Driving Behavior

...........19

Parent-Teen Driving Agreements

.........19

Peer-to-Peer Programs .................................20

Conclusion ...................................................................21

References .................................................................23

Appendix 1.................................................................. 25

Appendix 2 .................................................................26

Executive Summary

The U.S. has a speeding problem. Driving at high rates of speed or too fast for conditions is one

of the most prevalent factors contributing to serious and fatal crashes on our nation’s roadways.

Over the past ve years (2015-2019), speeding has claimed the lives of approximately one-third of

all people killed in motor vehicle crashes. While speeding is risky for all drivers, it is particularly

problematic for teens 16 to 19 years of age. A closer look at the speeding data reveals a troubling

and persistent trend—teen drivers and their passengers accounted for a greater proportion of

speeding-related fatalities than all other motorist age groups (43% versus 30%).

Why the disparity? Teen drivers do not have the experience necessary to recognize and quickly

react appropriately to dangerous situations, which makes speeding even riskier for them. This

propensity to speed, however, is not innate. Teens learn about speeding at an early age, as they

ride in vehicles driven by their parents and other adults and observe persistent speeding behavior.

They are likely taught by driver education professionals and/or their parents that speeding is

dangerous. But as teens gain condence behind the wheel, their travel speeds are likely to

increase and be exacerbated by other drivers on the road. For teens, like the adults they grew up

riding with, keeping up with trafc—even if it requires going well over the speed limit—becomes

the norm.

This report examines what we know about speeding-related teen driver fatal crashes—the driver

was more likely to be male (37% versus 28%), have run-off the road or rolled over the vehicle

and to be unbelted. While the youngest teen drivers (16- and 17-year-olds) have the highest fatal

crash risk due to lack of experience, their older counterparts (18- and 19-year-olds) are more likely

to crash later at night (midnight to 5 a.m.) and on highways and freeways. And when it comes to

passengers, the risk of a teen driver being involved in a speeding-related fatal crash increases

exponentially with each additional peer in the vehicle.

Breaking this deadly cycle is critical for driving down serious injuries and deaths involving teen

drivers and their passengers. The good news is that this problem is not insurmountable. This

report identies some of the best no-tech, low-tech and high-tech resources (many of which are

free) available to help families rein-in their speeding teens—and for parents to monitor their own

driving speeds, as well. These include parent-teen driving agreements, state graduated driver

licensing systems, peer-to-peer and parent-education programs, online training, and in-vehicle

safety technology. Even a teenager’s cellphone can be tapped to deliver information to mom and

dad about their speeding and other driving behaviors via free or low-cost apps.

The key is convincing parents to not only learn about and leverage these resources, but also to

recognize the danger speeding poses for their teen drivers and take appropriate action. The

former is the job of the State Highway Safety Ofces and their partners working in the teen

driving arena, which is why this report includes recommendations directed specically at them.

PAGE 3 of 25

PAGE 4 of 27

Introduction

Losing a child is, without a doubt, a parent’s worst nightmare. But sadly, each year there are parents

in the United States (U.S.) that nd themselves in the unimaginable position of making nal

arrangements for their teenage child killed in a motor vehicle crash, rather than organizing birthday

parties or graduation celebrations. As shown in Figure 1, despite welcome declines in the number of

trafc fatalities involving teenage drivers and passengers in 2018 and 2019, more than 2,000 U.S.

teen vehicle occupant deaths occured each year. The data in this report come from the National

Highway Trafc Safety Administration’s (NHTSA) Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS).

For all teen driver and passenger fatalities during that same 5-year period, 43% involved

speeding. By comparison, 30% of fatalities involving drivers and passengers ages 20+ were

speeding-related (Figure 2). A total of 4,930 teen drivers and passengers were killed in these

speeding-related crashes. A state-by-state breakdown of teen driver and passenger fatalities for

this 5-year period is provided in the Appendix.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), motor vehicle crashes are the

leading cause of death for U.S. teens

1

. The fatal crash rate per mile driven for 16- and 17-year-olds

is about three times the rate for drivers 20 and older

2

. Based on police-reported crashes of all

severities, the crash rate for 16- to 19-year-olds is nearly four times the rate for drivers 20 and older.

Risk is highest at age 16.

In addition to having higher death rates, teen drivers pose a greater danger to others on the road.

They pose the highest risk of death to their passengers, occupants of other passenger vehicles

and non-vehicle occupants such as pedestrians and cyclists

3

.

Risk factors for teen crashes include inexperience, impulse control, lower seat belt use rates than

other age groups

4

and speeding. This report focuses on speeding.

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

2015 2019201820172016

2,380

2,078

2,159

2,382

2,420

FIGURE 1 >>

Teen Drivers and Passengers

Killed in Motor Vehicle

Crashes, 2015–2019

PAGE 5 of 27

The U.S. has a speeding problem. Driving at high rates of speed or driving too fast for conditions is

one of the most prevalent factors contributing to serious and fatal crashes for drivers of all ages.

Speed limits are routinely violated and many drivers freely admit to speeding on a regular basis

5

. In

recent years, many states have raised speed limits with some having maximum posted speed limits

of 75 mph or higher. The result of higher speed limits is even higher vehicle speeds

6

.

Speeding increases both the likelihood of being in a crash and crash severity. Vehicles traveling

at higher speeds cover a greater distance between the time a hazard is detected and the time the

driver reacts, so the vehicle will travel farther before coming to a stop. Higher speeds also increase

crash energy forces. This compromises a vehicle’s ability to protect occupants against serious and

fatal injuries, even with substantial improvements in vehicle crashworthiness (e.g., steel reinforced

safety cage, air bags, three-point seat belts, crumple zones). And even small increases in travel

speed have signicant, often deadly, consequences when a vehicle collides with a pedestrian or

bicyclist.

While speeding is a risk factor for all drivers, teenagers (and other novice drivers) are at greater

risk for serious crashes when speeding. Traveling at higher speeds or at speeds too fast for

conditions reduces the amount of time drivers have to react to unforeseen dangers such as loss

of control on slick pavement or a child or deer running into the road. Teen drivers are in the early

stages of gaining the experience needed to recognize and get out of dangerous situations, which

makes speeding even more risky.

Despite clear evidence of the harmful effects of speeding on fatal crashes, speeding by teen

drivers continues to claim thousands of lives each year. This report provides the latest data on

speed-related fatal crashes among teen drivers and evidence for their increased propensity

to speed. It points to possible reasons for the speeding problem and suggests potential

countermeasures as well as recommendations for possible implementation by the State Highway

Safety Ofces and their partners.

Teen drivers

and passengers

(Ages 13-19)

Drivers and

passengers

(Ages 20+)

43% 30%

FIGURE 2 >>

Percent of All Driver and

Passenger Deaths that

Were Speeding Related,

2015–2019

PAGE 6 of 27

Size and Nature of the Problem

Speeding-related Fatal Crashes Among Teen Drivers

From 2015 to 2019, 15,510 teen drivers ages 16 to 19 were involved in fatal motor vehicle crashes.

More than one-third of those crashes—5,202—involved speeding as documented in FARS.

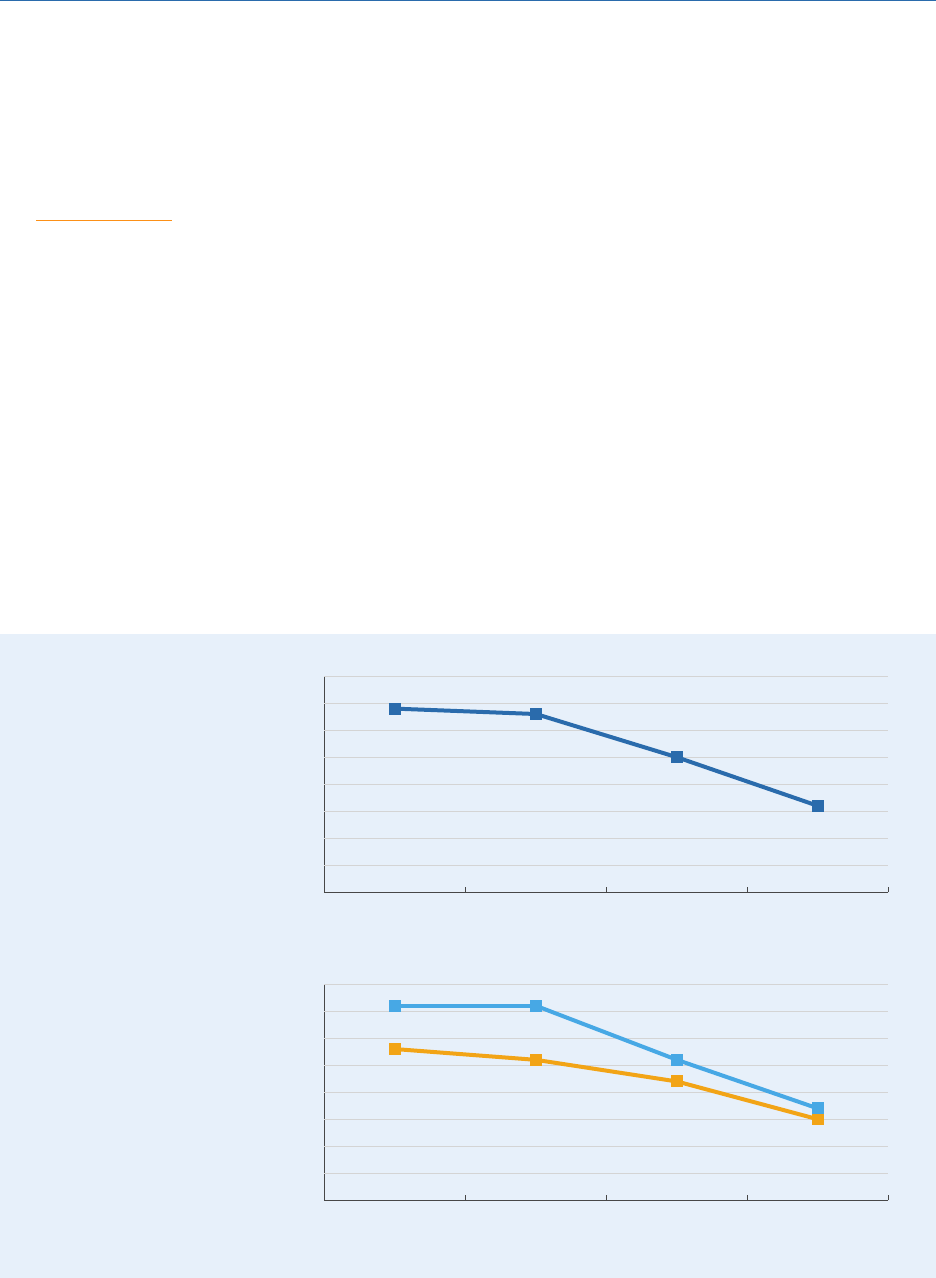

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the percentage of all speeding-related fatal crashes by driver age and

gender for the ve-year period. (Throughout the remainder of this report, passenger vehicle is

referred to as vehicle.)

The youngest drivers (ages 16 to 19) had the greatest proportion of fatal crashes involving

speeding (34%), followed closely by 20- to 29-year-old drivers (33%).

Male drivers in every age group account for the greatest proportion of fatal crashes involving

speeding, although the disparity with female drivers diminishes with age. The youngest drivers

(ages 16 to 19) of both sexes have the greatest proportion of fatal crashes involving speeding, with

36% of males and 28% of female teen drivers involved in these crashes.

In many speeding-related fatal crashes, drivers fail to keep their vehicles on the road. Roadway

departure often results in high-speed collisions with trees, utility poles, culverts, parked cars and

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

65+30-6420–2916–19

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

65+30-6420–2916–19

34%

33%

25%

16%

36% 36%

26%

17%

15%

22%

26%

28%

Driver Age

Driver Age

FIGURE 3 >>

Percent of All Fatal Crashes

that were Speeding-Related

by Driver Age, 2015–2019

FIGURE 4 >>

Percent of All Fatal Crashes

that were Speeding-Related

by Driver Age and Gender,

2015–2019

n Male

n Female

PAGE 7 of 27

other roadside objects. As shown in Figure 5, the youngest drivers (16- and 17-year-olds) had the

highest percentage of fatal, speeding-related crashes resulting in roadway departure (71%),

with the rate declining as drivers age. High levels of roadway departure for young drivers most

likely reects a lack of experience in selecting appropriate speeds for driving conditions and could

also be associated with driver distraction and alcohol/drug impairment.

Another major risk factor in speeding-related crashes is vehicle rollover, which can be dangerous

and deadly. As shown in Figure 6, the youngest drivers (16-year-olds) had the highest percentage

of speeding-related fatal crashes involving rollover (41%), with a slight, gradual decline in the

rate as drivers age. As with roadway departure, higher levels of young driver rollover crashes

might reect a lack of experience in selecting appropriate speeds for driving conditions, as well as

inappropriate response to sudden changes in driving conditions at high speeds.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

Driver Age

LANE

DEPARTURE

50+40–4930–3920–2919181716

71%

71%

68%

65%

62%

58%

55%

52%

FIGURE 5 >>

Percent of Speeding-Related

Fatal Crashes that Involved

Roadway Departure by

Driver Age, 2015–2019

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

Driver Age

50+40–4930–3920–2919181716

41%

35%

37%

33% 33%

32%

30%

26%

FIGURE 6 >>

Percent of Speeding-Related

Fatal Crashes that Involved

Rollover by Driver Age,

2015–2019

PAGE 8 of 27

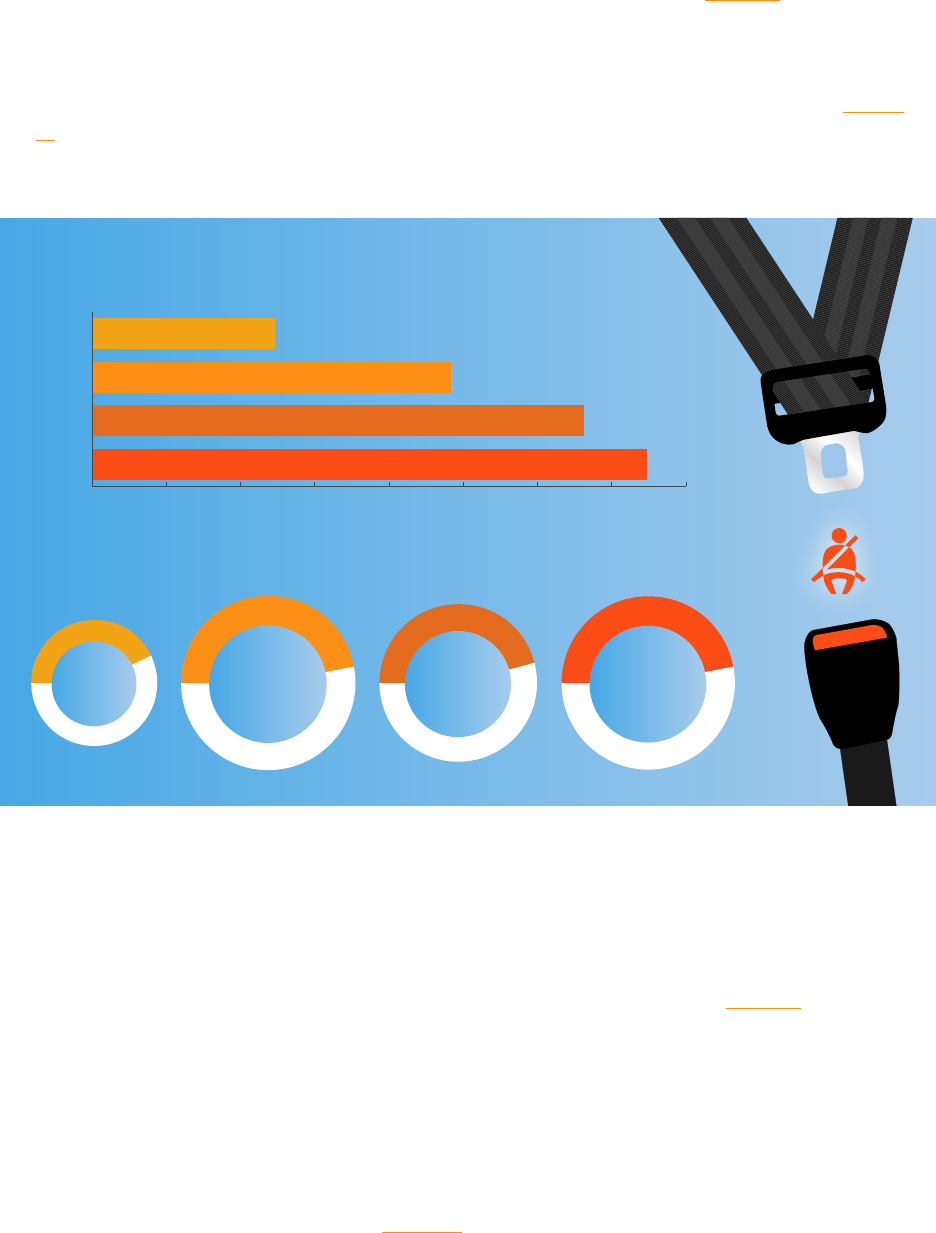

Driving after dark is riskier than daytime driving for several reasons, including higher travel speeds

due to emptier roads, driver fatigue and a higher prevalence of alcohol impairment. As shown in

Figure 7, the percent of speeding-related fatal crashes that occurred at night among teen drivers

was lowest for 16-year-olds and increased with age. For 16- to 19-year-old drivers combined,

51% of all fatal crashes occurred in the dark. The increasing percent of nighttime crashes as teen

drivers age is likely due to parental restrictions and/or state Graduated Driver License (GDL) laws

limiting nighttime driving by the youngest novice teen drivers.

Similarly, late night hours, such as midnight to 5 a.m., can be particularly risky, especially for

young drivers. As shown in Figure 8, the percent of speeding-related fatal crashes that occurred

between this time period among teen drivers was also lowest for 16-year-olds and increased

with age. As teens age and earn additional nighttime driving privileges, they are at increased risk

of being involved in deadly late-night crashes.

All occupants of a vehicle should wear seat belts—on every trip. However, due to their higher-crash

risk, it is especially important that teens always wear seat belts. Today’s teens grew up with car

FIGURE 7 >>

Percent of All Speeding-Related Fatal

Crashes that Occurred at Night by Driver

Age: 2015–2019

FIGURE 8 >>

Percent of All Speeding-Related Fatal

Crashes that Occurred from Midnight to

5 AM by Driver Age: 2015–2019

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

50+

40–49

30–39

20–29

19

18

17

16

Driver Age

44%

47%

32%

53%

54%

58%

53%

46%

Percentage

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

50+

40–49

30–39

20–29

19

18

17

16

Driver Age

11%

15%

8%

22%

22%

28%

21%

15%

Percentage

PAGE 9 of 27

seats and seat belts, which should make it natural for them to buckle up. Yet sadly, more than half

of all teen drivers killed in speeding-related crashes were unrestrained. As Figure 9 shows, the

number of unrestrained fatally injured teen drivers increased with age. This could be the result

of exposure (e.g., number of licensed drivers by age, amount of time spent driving by age) and that

teenagers typically feel more comfortable driving at higher speeds as they gain experience. This

level of comfort may also result in lower seat belt usage rates as teenagers age. As shown in Figure

10, the percent of fatally injured teen drivers in speeding-related crashes that were unrestrained

was lowest for 16-year-olds, and higher for 17-,18-, and 19-year-olds.

It is well known the presence of one or more teen passengers in a teen driver’s vehicle has

been shown to negatively affect driver behavior and increase crash risk

7

. Teen passengers, for

example, can goad the driver on or the driver could be showing off to friends. In some cases,

passengers could physically interfere with the driver (e.g., grabbing the steering wheel). This

problem is exacerbated with higher numbers of teen passengers in the vehicle. Figure 11 shows

the percentage of teen driver (ages 16 to 19) speeding-related fatal crashes by teen passenger

presence. For both male and female teen drivers, the rate of fatal crashes that were speeding-

related increased with each additional teen passenger in the vehicle.

Understanding where teen drivers are speeding—the road type—is also important. Public roads

generally fall into three categories: freeways such as interstates and limited access-highways;

non-freeway arterials, typically the main roads that carry local and regional trafc through

communities; and collector/local roads. Figure 12 shows the percentage of speeding-related fatal

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400

19

18

17

16

123

242

374

331

Driver Age

43%

Driver Age

16

47%

Driver Age

17

46%

Driver Age

18

47%

Driver Age

19

FIGURE 9 >>

Number of Fatally Injured Unrestrained Teen Drivers in Speeding-Related Crashes, 2015–2019

FIGURE 10 >>

Percent of Fatally Injured Teen Drivers in Speeding-Related Crashes that were Unrestrained by Age, 2015–2019

PAGE 10 of 27

crashes by roadway category. Note that teen speeding is not conned to freeways. In fact, it is

more likely to occur on non-freeway and local roads.

Interstates and other freeways have features that promote safety (e.g., median barriers to help prevent

head-on collisions; elimination of intersections and crossing-path collisions through limited access),

and speed limits and travel speeds are highest on these roadways, which can be a signicant challenge

for novice drivers. For this reason, many young drivers limit or delay driving on Interstates and other

freeways, or travel more slowly than other drivers on these high-speed roads. As young drivers gain

experience, they may be more willing to travel on Interstates and other freeways, and/or travel at

22%

29%

48%

16%

37%

47%

14%

40%

46%

9%

50%

41%

5%

54%

39%

Driver Age

0

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

20+19181716

FIGURE 12 >>

Percent of Speeding-Related

Fatal Crashes by Roadway

Type, 2015–2019

n Freeway

n Non-Freeway Arterial

n Collector/Local

FIGURE 11 >>

Percent of Speeding-Related

Fatal Teen Driver Crashes by

Teen Passenger Presence,

2009-2018

n Driver Alone

n 1 Teen Passenger

n 2 Teen Passengers

n 3+ Teen Passengers

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

Male Female Total

20%

26%

24%

22%

18%

25%

21%

19%

21%

26%

25%

23%

PAGE 11 of 27

higher speeds on these roads. This likely explains why the percent of all fatal crashes that occur on

Interstates and other freeways increases steadily with driver age through the teen years.

Why the Problem Exists

Elevated crash rates for teen drivers result both from inexperience and immaturity. Young drivers are

still learning critical driving skills that experienced drivers take for granted. And teenagers are still

developing physically, mentally and emotionally. Lack of experience behind the wheel makes it more

difcult for teenagers to assess potential crash risks, such as speeding, as well as to recognize and

respond to hazards when they occur. While the relative contribution of driver age versus inexperience

has long been debated, the effects of experience are clearly demonstrated by a steep drop in crash

rates, especially among the youngest drivers, during the rst few months of driving

8

.

Developmental Issues

Adolescents’ brains differ from those of adults in important ways. Higher teen driver death rates

are reported to be related to problems with behavior and emotion control

9

. The human brain isn’t

fully developed until the early to mid-twenties, particularly the prefrontal cortex where impulse

control, decision making and judgment are centered, thus compromising important functions

related to safe driving. Some teenagers may also be impulsive, thrill seeking and more drawn to

the rewards of risky behavior rather than wary of the negative consequences of such behaviors.

Driver Skills and Driving Behavior

Learning to drive safely takes time and extended practice, regardless of age. Many skills must

be mastered. New drivers usually learn maneuvering skills such as steering, accelerating and

braking relatively quickly. Meanwhile, more complex tasks such as visual search, risk and hazard

perception, and appropriate responses to the latter, come with practice over a longer time period.

Novice drivers’ attention can be easily overloaded such that their ability to pay attention to multiple

activities on the road (e.g., pedestrians and cross trafc) is limited. There is evidence novice drivers

are less able to assess hazards in the trafc environment and their visual search patterns are less

attuned to detect potential future risks

10

. Observational studies have documented the tendency

for teen drivers to speed and allow shorter following distances

11 12

. These risky behaviors are

exacerbated in the presence of teen passengers.

Reducing the Problem

One of the biggest challenges in addressing the dangers of speeding is

that this behavior is widely accepted nationwide. The U.S. has a culture

of speeding in which many drivers view speed limits as minimums rather

than the maximums based on ideal conditions. According to the “2019

AAA Safety Culture Index,” 48.3% of motorists reported exceeding the

posted speed limit by 15 mph on highways, while 41.5% admitted driving

10 mph over the posted speed limit on residential streets in the past month

13

.

The latest speed research conducted for NHTSA conrms what the motoring

public admits: 68% are exceeding the posted speed limit on limited access

roads and 56% and 58% are doing so on arterials and collectors, respectively.

SPEED

LIMIT

70

The U.S. has a culture of

speeding in which many

drivers view speed limits

as minimums rather

than the maximums.

PAGE 12 of 27

Approximately 16% to 19% of these motorists are also traveling more than 10 mph over the posted

speed limit

14

.

Although speeding has long been recognized as a critical factor contributing to fatal teen

crashes, effective measures to reduce the problem have been elusive. Potential countermeasures

include driver training, safety education, state GDL laws that set a minimum age at which teens

may obtain a driving permit and license and restrictions on when teens can drive and with whom,

speed enforcement, and a growing array of in-vehicle technologies. The remainder of this report

addresses various approaches to help reduce the teen speeding-related crash problem and

recommendations for consideration by the SHSOs.

Speed Limits and Speed Enforcement

Speed limits and their enforcement have the potential to deter teen drivers from speeding, but

most law enforcement agencies have insufcient stafng resources to conduct rigorous, sustained

speed enforcement campaigns. In addition, some law enforcement ofcials believe public concerns

about perceived racism in trafc enforcement might be a factor in the apparent slowdown in trafc

enforcement by police

15

. Although police speed enforcement activities do not specically target

drivers by age, law enforcement agencies could conduct periodic speed enforcement at crash-

prone locations frequented by younger drivers, such as near high schools or shopping malls.

While automated trafc enforcement (e.g., safety cameras) has been shown to dramatically reduce

speeding behavior

16

, many states either prohibit this technology, do not expressly authorize its use,

or restrict cameras to school and/or work zones.

Recommendations

Partner with community advocates, parents and others concerned about speeding to educate

elected ofcials, the media and key inuencers about the effectiveness of automated speed

enforcement (safety cameras) as a supplement to traditional police enforcement. A checklist,

developed by AAA, Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, the Insurance Institute for

Highway Safety and the National Safety Council, for implementing red light camera programs

can serve as a useful resource for automated speed enforcement

17

.

Identify speeding-related teen-driver crash hot spots and partner with local police agencies to

conduct enforcement.

Driver Education and Training

Beginning drivers need training to learn basic driving skills, as well as to master more advanced

techniques over time. Driver education enjoys widespread public support as the preferred way to

prepare teenagers for driving. There is mixed evidence regarding the effectiveness of traditional

driver training in reducing crashes among young drivers. Several comprehensive international

reviews of the best scientic evaluations of driver education programs for young beginners

concluded there is no difference in the crash records of driver education graduates compared with

equivalent groups of beginners who learned to drive without formal education

18

.

PAGE 13 of 27

Newer research conducted in Nebraska, however, investigated whether teens who obtained

their intermediate-level provisional operators permit (POP) in a GDL environment through driver

education had fewer crashes and trafc violations then teens who obtained their POP by completing

a supervised driving certication log in lieu of taking driver education. A descriptive epidemiological

study examining a census of all 151,880 teen drivers in Nebraska from 2003 to 2010 found the

driver education cohort had signicantly fewer injury and fatal crashes and violations than the

certication log cohort during the rst two years of driving following receipt of their POP

19

.

In partnership with the American Driver and Trafc Safety Education Association, GHSA and

several other safety-related organizations, NHTSA developed driver training curricula and

administrative standards. NHTSA also developed a driver education program assessment tool to

help states conduct a comprehensive review of their education and training programs to determine

where improvements can be made.

Computer-based curriculum provides another option for delivering teen driver education and

training with more consistency and convenience, though safety outcomes vary. For example:

» Researchers tested a stand-alone, self-administered training module intended to accelerate

the process of perceptual expertise for young, novice drivers among a small sample of young

drivers

20

. Five out of the six pilot-study participants demonstrated robust improvements in all

learning categories included in the training – path conict, stopping vehicle, roadside incursion,

forced path change, obscured potential hazard and emergency vehicle effects. While this

approach appears promising, the study did not examine the training’s effect on actual driving

skills or crash risk and whether these effects are long-lasting.

» Researchers developed and evaluated Accelerated Curriculum to Create Effective Learning

(ACCEL), a computer-based training program that can be downloaded from the Internet on any

personal computing device (e.g., laptops, smartphones, tablets)

21

. The program targeted six

skills based on a literature review of factors linked to novice driver crash risk. The researchers

found the ACCEL training group performed better than the placebo training group in ve of the

six skills, with tactical hazard mitigation performance marginally better for the ACCEL group

as compared to the placebo group. The study also examined whether the skills were sustained

three to six months post-training and the effects of a second ACCEL training session. Findings,

however, were limited due to high participant attrition. Overall, the ACCEL training program

accelerated the development of novice drivers’ strategic and tactical hazard anticipation and

attention maintenance skills across the riskiest crash scenarios.

» Ford Driving Skills for Life offers The

Academy, a free online resource to help

teens “test [their] safe driving knowledge

and gain valuable safe driving skills.” The

Academy also includes a Parent-Teen Driver

Agreement (see page 19 for more information

on this proven tool), and science-based

resources that use algebra and biology to

reinforce critical trafc safety concepts

22

.

PAGE 14 of 27

A number of high-performance driver training programs are available for parents that want to

expose teens to emergency driving exercises such as hard braking, emergency lane change and

slide recovery, and skid control, as well as cognitive skills like hazard anticipation, visual scanning

and situational awareness.

Recommendations

Promote state adoption of the national driver training curricula and administrative standards.

Use the NHTSA driver education program assessment tool to conduct a comprehensive review

of your state’s driver education and training programs to determine where improvements can

be made.

Provide and/or promote resources and programs that build upon driver education and training

to help teens develop higher order driving skills.

Conduct research to determine whether teens in your state that complete mandated driver

education have lower crash and violation rates than teens who do not complete mandated

driver education.

Graduated Driver Licensing

Graduated Driving Licensing (GDL) is widely recognized as one of the most

effective approaches for reducing the risk of teen crashes. GDL restricts

teen driving to times of the day and situations that are considered lower risk.

According to NHTSA, this approach can reduce teen crash risk by as much

as 50%

23

. GDL addresses well-known high risks for novice drivers by limiting

driving at night and with teen passengers during the initial six to 12 months

of licensure, only allowing unrestricted driving after more experience has

been gained.

The effects of GDL specically on teen speeding behavior have not been established by research.

But limiting driving under conditions for which speeding is known to be more prevalent — at night

(when roads are emptier) and with teen passengers – is critical and both restrictions are shown to

reduce teen crash risk. Stronger GDL laws lead to the greatest crash reductions

24

. GHSA maintains

a list of current state GDL laws.

Some states do not allow teen drivers to advance from one phase of GDL to another if they have

been convicted of certain trafc violations such as racing and reckless driving. Penalties for

serious trafc offenses committed by teen drivers in some states include license suspension,

which temporarily takes away driving privileges and delays advancement through the GDL process.

GDL restricts teen

driving to times of the

day and situations

that are considered

lower risk. This

approach can reduce

teen crash risk by as

much as 50%.

PAGE 15 of 27

Recommendations

Promote Graduated Driver License law effectiveness in reducing teen crash risk and raise

awareness of why restricting late night driving and passengers may help reduce teen

speeding.

Pursue inclusion of GDL phase advancement restrictions for speed-related violations, a best

practice all GDL systems should include.

Partner with your state licensing agency to conduct research assessing GDL’s impact on

reducing teen driver speeding violations and crashes.

Parents’ Role

Beyond government laws and restrictions, parents can take an active role in helping to reduce teen

crashes. The following noteworthy approaches are available to families of teen drivers.

In-vehicle Driver Monitoring

Many parents worry about how safely their teens are driving when they’re unsupervised. When

asked about their specic concerns, the number one issue for parents was speeding. More than

half said they’d want to know if their teen was speeding

25

.

Fortunately, a growing number and variety of aftermarket devices are available that employ

computer chips, GPS systems and video-based recorders to assist parents in monitoring and

controlling teen driving behavior. There is some evidence that in-vehicle monitoring of novice

teen drivers can result in less risky driving

26 27

. Whether in-vehicle monitoring can be an effective

countermeasure depends on whether teens change their driving behavior. For that to happen,

parents need to be engaged and use the information provided by these systems to coach their teen

drivers. However, parents’ interest in checking on their teens’ driving behavior is not universal and

diminishes over time

28

, which reduces the potential effectiveness of in-vehicle driver monitoring.

In addition to aftermarket devices, some vehicle manufacturers offer equipment that allows

parents to limit certain types of teen driving behavior. For example:

» Ford’s MyKey© Technology is a standard

feature on all Ford and Lincoln models

that offers a special teen driver key

parents can program to limit the vehicle

top speed to 80 mph and provide

audible warnings at speeds of 45, 55

and 65 mph

29

. MyKey also includes a

“Belt-Minder” that not only chimes but

mutes the vehicle’s audio speakers

PAGE 16 of 27

until the driver is buckled up. According to Ford, parents of teen drivers are supportive of the

technology, with 75% saying they like the speed limiting feature. Systems such as MyKey have

the potential to reduce speeding-related crashes, although no studies have examined their

effectiveness.

» Volvo offers Care Key in-car technology in 2021 models, which is aimed at addressing speeding.

With Care Key, Volvo owners can apply a speed cap when younger family members or less

experienced drivers are behind the wheel. Also, starting with all 2020 models, Volvo capped its

top vehicle speed at 112 mph.

» Chevrolet offers Teen Driver Technology, a built-in system that allows parents to set a speed

alert and limit the top speed to 85 mph, set a volume limit that includes muting the audio until

the driver and front seat passenger are buckled up, and receive the industry’s rst and only

in-vehicle report card. Parents can use this information to identify potential problem areas and

provide guidance.

Smartphone Apps

Although cellphone use behind the wheel is strongly discouraged, and is generally restricted or

prohibited, smartphone apps have been developed to support safe driving behavior. The prevalence

of cell phone use among teen drivers presents an opportunity for parents to use a growing number

of smartphone apps to keep tabs on how teens are driving and supports parents’ efforts to

discourage unsafe teen driving behaviors, including:

» Life360 is designed to keep families connected by providing parents the ability to monitor teen

driving in real time. The app includes a driver safety mode that can track locations and monitor

speed, and send text message alerts for hard braking, rapid acceleration and even crashes

30

.

» Built into specic models, the Hyundai Blue Link app enables parents to set custom, pre-set

notications that tell them when their teens exceed the speed limit

31

.

» Bouncie provides parents access to real-time driving

insights, including notications for speed, acceleration,

hard braking, idle time and more

32

. Events for each trip

are summarized and available for review anytime, giving

parents the ability to monitor their teens’ safe driving

progress overtime.

» State Farm offers the app-based Steer Clear discount

program for teens, which is promoted as a way for “teen

and young adult drivers to improve their driving skills and

earn a discount” on auto insurance

33

.

» American Family Insurance’s Teen Safe Driver app monitors

teen drivers’ risky behaviors and sends alerts to their

smartphones. Parents also have the app on their phones,

enabling them to keep an eye on their novice driver and

Life360 Blue Link Bouncie

Steer

Clear

Teen Safe

Driver

PAGE 17 of 27

take corrective action as necessary. Insured families receive a 10% discount after their teens

complete 3,000 miles or one year in the program

34

.

In-Vehicle Safety Technology

When purchasing a new vehicle or deciding which family vehicle should be driven by teen drivers,

parents should consider the role of in-vehicle safety technologies. These include:

» Lane-keeping assist, which provides feedback to drivers when straying out of the travel lane.

» Automatic emergency braking, which automatically activates the vehicle’s brake system, to

some degree, when necessary.

» Adaptive cruise control, which automatically adjusts vehicle speed to maintain a safe distance

from vehicles ahead.

» Speed limit recognition, which can warn drivers when they’re exceeding the speed limit.

These advanced safety features are available on many vehicles as either standard or optional

equipment.

It is important to note safety technologies such as those described above

are intended to support—not serve as a substitute for—a safe and engaged

driver nor are they a substitute for parental involvement in the teen driver

learning and skill building process. The use of driver monitoring devices

requires candid conversations between parents and teens. It is important they

agree on the role of these technologies in reinforcing safe driving behaviors

and habits, which should have already been taught to teen drivers by their

parents and driving instructors. Safety technologies can serve as guardrails to remind teens in

real-time when their driving actions or decisions are putting them at risk. It also is important

for parents to learn how their vehicles’ safety features work and to convey this information to

their teen drivers. This goes for smartphone apps, as well. But most importantly, parents should

regularly reinforce with their teens that a safe driver is a vehicle’s most important and effective

safety feature.

Recommendations

Promote parental use of in-vehicle safety technology, apps and other tools to monitor and

coach their teen drivers throughout and beyond the rst year of licensure.

Partner with automakers and dealer groups to educate driver education and training

instructors and parent-teen driving program providers about the newest vehicle safety

features and how they work to reduce crash risk.

Include information about vehicle safety features in teen driving educational materials.

In-vehicle safety

technology is

intended to support

— not serve as a

substitute for — a

safe and engaged

driver.

PAGE 18 of 27

Parental Involvement in the Learning-To-Drive-Process

Many programs are available to help parents better understand the risks for their novice drivers

and what they can do and use to help address those risks. Some examples include learning about

and enforcing GDL requirements including developing a parent-teen driving agreement, coaching

and monitoring their teens, being positive

role models and controlling the car keys.

Because today’s parents learned to drive

under very different conditions and with

far less prescriptive driver licensing

laws, educational programs are key to

encouraging informed parental involvement.

Some states, nonprots and insurance

companies have developed and/or fund

parent education/orientation programs

that show promise in engaging parents and

teens to work together as the latter get

behind the wheel

35

.

Research conducted on the effectiveness of teen driving parent education/orientation program

identied the following key components for success

36

:

» Be evidence-based and grounded in research

» Provide clear guidance for parent action

» Have repeated contacts with parents

» Incorporate principles of adult learning

» Explain the rationale for GDL and the role of parents

» Be designed and conducted by individuals outside the driver education system

» Have systems in place to ensure the program is standardized and delivered consistently

» Evaluate outcomes

» Mandate parent attendance

Some of these programs address the critical role parents play in controlling the keys, which

involves making (sometimes) tough decisions about when teenagers are not allowed to drive the

family vehicle. Vehicle ownership is also a factor to consider. Teens often drive smaller and older

vehicles that offer less protection than larger and newer vehicles in a crash. Several studies have

shown that teens considered to be the primary owner of a vehicle are more likely to speed

37 38

, so

parents should think carefully about providing teens their own vehicle when rst licensed.

This parent involvement is important. Research from The Children’s

Hospital of Philadelphia found that teenage drivers with authoritative

(actively involved) parents were half as likely to be involved in a crash,

71% less likely to drive intoxicated, and 30% less likely to use a cell

phone when driving compared to teens with uninvolved parents. These

same teens were also 50% more likely to buckle up and recognize why

50%i

Research shows

teen drivers with

authoritative parents

are half as likely to be

involved in a crash.

PAGE 19 of 27

doing so is important

39

. Authoritative parents provide a warm supportive environment with clear

boundaries giving them enough structured support to allow them to make good choices.

Recommendations

Provide and/or fund teen driving parent education/orientation programs that have the

components for success discussed on page 18.

Incorporate data about the positive impact actively involved (authoritative) parents have on

their teens’ safe driving behaviors in trainings and educational materials.

Educate parents about the importance of controlling the keys and the propensity for teens

that own their own vehicles to speed.

Modeling Safe Driving Behavior

The behavior and actions of parents can have signicant inuence over their children’s driving

behavior. Teenagers learn from watching their parents. Parents are their teens’ rst driving

teacher and coach and their biggest inuencer. Research shows that teens welcome their parents’

involvement, citing their parents as the number one inuence when it comes to learning to drive

40

.

It is important for parents to model safe driving behavior and be consistent in the messages they

tell their teens versus their own driving behaviors. By not speeding, driving aggressively or driving

distracted or impaired, parents can model the type of safe driving behavior they expect their teen

drivers to exhibit.

Modeling safe driving behavior includes slowing down during inclement weather. New teen drivers

need to learn how vehicles react in inclement weather and may not appreciate the risks of driving

in rain, fog, ice and/or snow. Parents teaching their teens how to drive should take them out on

a rainy or snowy day and let them learn how vehicles react with less traction and how reducing

speed can help them better maintain control on slick road surfaces.

Recommendation

Include an inclement weather driving lesson that includes a focus on speeding in novice driver

training materials provided to parents.

Parent-Teen Driving Agreements

Conversations between parents and teens about safety can help ensure teens make better

decisions behind the wheel. Parent-teen driving agreements serve as a tool to prompt discussion

and ongoing dialogue about safety. Researchers at the CDC and other safety and health-related

organizations strongly recommend parents use an agreement that clearly outlines the rules of the

road with their new drivers

41

. Examples of parent-teen driving agreements (PTDA) are available

online and most cover the key risk factors for teens including driving at night, passengers, cell

phones and texting, seat belts, and the use of alcohol. At minimum, a PTDA should outline the

PAGE 20 of 27

provisions in a state’s GDL and other motor vehicles laws including obeying speed limits, and the

consequences for violating them.

Recommendation

Promote parents and teens working together to develop a parent-teen driving agreement that

at minimum addresses the requirements in your state’s GDL law and obeying posted speed

limits, along with the consequences for violating those requirements.

Peer-to-Peer Programs

In addition to learning safe driving behaviors and habits from parents

and driving instructors, teens can be encouraged by their peers to act

safely and responsibly behind the wheel. Because teens who regularly

participate in positive social projects designed to help their peers

and others are less likely to engage in risky behaviors

42

, peer-to-peer

trafc safety programs are an important part of a broader strategy for

preventing teen driver crashes and the resulting injuries and fatalities.

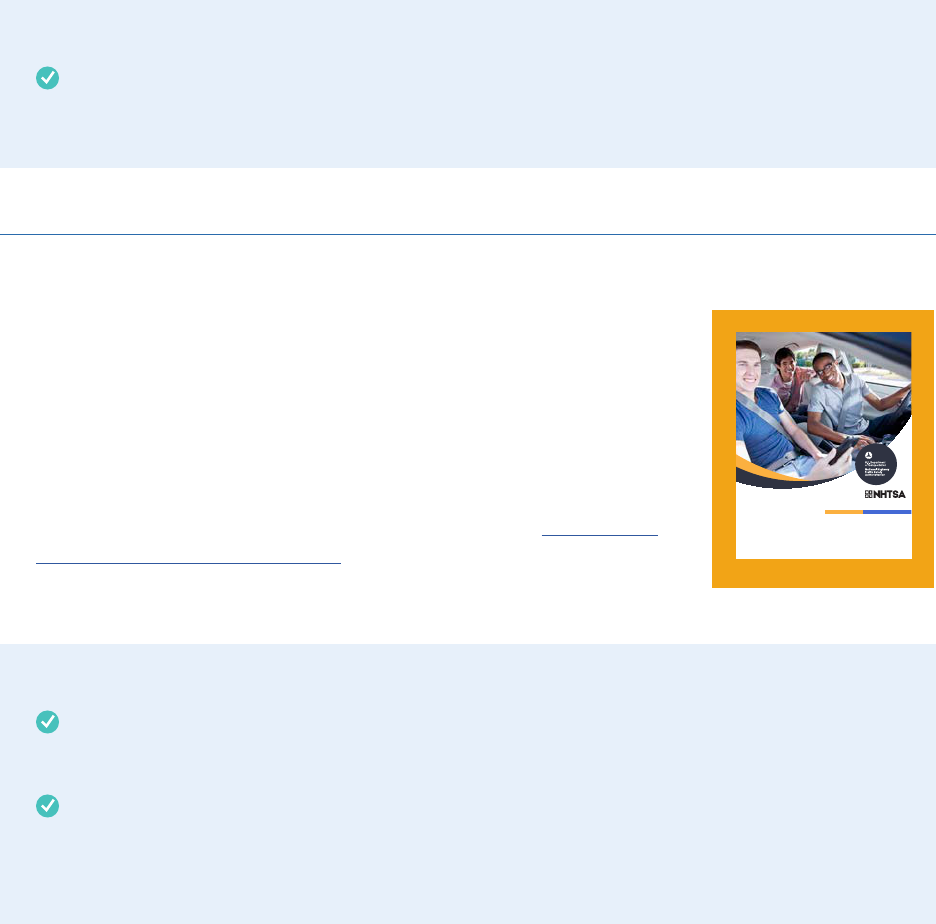

NHTSA partnered with GHSA to publish a comprehensive Peer-to-Peer

Teen Trafc Safety Program Guide that can support community efforts

to establish effective peer-to-peer teen driver safety programs

43

.

Recommendations

Develop and implement or fund peer-to-peer trafc safety programs that incorporate the

essential elements discussed in the NHTSA “Peer-to-Peer Teen Trafc Safety Guide.”

Work with peer-to-peer programs such as Students Against Destructive Decisions (SADD)

and Family, Career & Community Leaders of America (FCCLA) to educate teen leaders

and advisors about teens’ overinvolvement in speeding-related fatal crashes and proven

countermeasures for addressing this problem.

PEER-TO -PEER

TEEN TRAFFIC SAFETY

PROGRAM GUIDE

PAGE 21 of 27

Conclusion

While speeding is a risk factor for all drivers, teenagers are at greater risk for serious crashes

when speeding. Analyses of fatal crash data conrm the signicant role speeding plays in teen

driver crashes:

» Among all age groups, teen drivers—of both sexes—have the greatest proportion of fatal crashes

involving speeding, with 36% of males and 28% of female teen drivers involved in these crashes.

» Teen drivers have the highest percentage of speeding-related fatal crashes that resulted in

roadway departure (71%) or rollover (41%).

» More than half of teen speeding-related fatal crashes occurred at night; 20% occurred between

midnight and 5 a.m.

» More than half of all teen drivers killed in speeding-related crashes were not wearing seat belts.

» The percent of fatal crashes that were speeding-related increased with each additional teen

passenger in the vehicle.

Inexperience and immaturity place teen drivers at greater risk of being involved in a fatal crash. In

addition, some teens lack impulse control and engage in risky behavior such as speeding. Higher

speeds increase both the likelihood of being in a crash and of being seriously injured or killed. Yet

the issue of speeding among teen drivers—and for drivers of all ages—does not garner as much

attention as other risk factors such as distracted, alcohol or drug impaired driving or have the same

social stigma. Increases in posted speed limits on some roads to 75 mph, 80 mph and even 85 mph

have sent the wrong message that high speeds are safe and acceptable.

Despite the proven benets of GDL, speeding-related teen crash rates remain high. Parents play a

critical role in their teens’ safety and are generally supportive of restrictions on their novice drivers

when rst licensed. Parents can be instrumental in decisions about when teens rst get their

licenses and what, where, when and how often they may drive the family vehicle.

There is clear evidence that young drivers speed more in the presence of their friends, so

passenger restrictions are particularly important. Limiting the number of teens (and siblings)

has been shown to reduce crashes, but there are still many fatal crashes involving teen drivers

transporting their peers.

Parents are concerned about their teens’ speeding behavior and are key to making a difference.

Impactful actions parents can take to reduce both teen speeding behavior and the risk of severe

crashes include:

» Getting—and staying—intimately involved in the learning-to-drive-process.

» Supplementing traditional driver education and training with plenty of supervised behind the

wheel practice as well as online tools, hands-on events and other resources.

» Consistently modeling safe driving behavior.

PAGE 22 of 27

» Establishing and enforcing rules about when their teens may drive and with whom.

» Ensuring the vehicles teens have access to are equipped with driver assist technologies.

» Using in-vehicle driver monitoring to track teen driving behavior and provide feedback

regarding speeding to promote the adoption of safe driving habits.

In addition to learning safe driving behaviors from parents and driving instructors, peer-to-peer

trafc safety programs are an important part of a broader strategy for preventing teen driver

crashes and the resulting injuries and fatalities.

Speeding is pervasive among drivers of all ages and a major contributing factor in all fatal crashes.

Teens learn to speed because it is the normalcy they observe and what becomes expected of them

when driving in trafc, regardless of what they are taught by parents or instructors. It is hard for

teens to adhere to or fully respect speed limits and other best safety practices when they do not

comport with the everyday driving experience. For these reasons, achieving progress in reducing

teen speeding-related crashes and fatalities has been a signicant challenge. The variety of tools

and resources presented in this report provide the best available approaches to support parents’

efforts to reduce teen speeding behavior and crashes.

PAGE 23 of 27

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Teen Drivers: Get the Facts. https://www.cdc.gov/

motorvehiclesafety/teen_drivers/teendrivers_factsheet.html Accessed 11-25-2020.

2. Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (2020). Teenagers. https://www.iihs.org/topics/teenagers Accessed 11-

25-2020.

3. Braver, E.R. & Trempel, R.E. (2004). Are older drivers at higher risk of involvement in collisions resulting in deaths

or non-fatal injuries among their passengers and other road users? Injury Prevention, 10, 27-32.

4. Enriquez, J. (2019). Occupant restraint use in 2018: Results from the NOPUS controlled intersection study (Report

No. DOT HS 812 781). Washington, DC: National Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

5. Schroeder, P., Kostyniuk, L., & Mack, M. (2013). National survey of speeding attitudes and behaviors (Report No.

DOT HS 811 865). Washington, DC: National Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

6. Retting, R.A. & Cheung, I. (2008). Trafc speeds associated with implementation of 80 mph speed limits on rural

interstates in West Texas. Journal of Safety Research 39: 529–534.

7. Williams, A.F., Ferguson, S.A., & McCartt, A.T. (2007). Passenger effects on teenage driving and opportunities for

reducing the risks of such travel. Journal of Safety Research, 38: 381-390.

8. Mayhew, D.R., Simpson, H.M., & Pak, A. (2003). Changes in collision rates among novice drivers during the rst

months of driving. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 35: 683-691.

9. National Research Council. (2007). Preventing teen motor crashes: Contributions from the behavioral and social

sciences. Washington, DC: National Research Council, Institute of Medicine, and Transportation Research Board

of the National Academies.

10. Ferguson, S.A. (2003). Other high-risk factors for young drivers – how graduated licensing does, doesn’t, or could

address them. Journal of Safety Research, 34: 71-77.

11. Simons-Morton, B., Lerner, N., & Singer, J. (2005). The observed effects of teenage passengers on the risky

driving behavior of teenage drivers. Accident Analysis and Prevention, 37: 973-982.

12. Goodwin, A.H., Foss, R.D., & O’Brien, N.P. (2012). The effect of passengers on teen driver behavior. (Report No. DOT

HS 811 540). Washington, DC: National Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

13. AAA Foundation for Trafc Safety. (2020, June). 2019 AAA Trafc Safety Culture Index, Washington, DC.

https://aaafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2019-Trafc-Safety-Culture-Index.pdf

14. DeLeonardis, D., Huey, R., & Green, J. (2018, March). National trafc speeds survey III: 2015. Washington,

DC: National Highway Trafc Safety Administration. https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.dot.gov/les/

documents/812485_national-trafc-speeds-survey-iii-2015.pdf

15. Kunkle, F. (2016, Oct. 5). Is Ferguson effect making nation’s highways unsafe? Some safety ofcials think so.

Washington Post.

16. Retting, R.A., Kyrychenko, S., & McCartt. A.T. (2008). Evaluation of automated speed enforcement on Loop 101 in

Scottsdale, Arizona. Accident Analysis and Prevention 40:1506-1512.

17. AAA, Advocates for Auto & Highway Safety, Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, and National Safety

Council (2018). Red light camera program checklist. https://www.iihs.org/media/1c936880-1816-44fe-ab57-

df603ad15714/ZjmPNA/News/2018/072418/RLC-program-checklist.pdf33333 Accessed 11-25-2020.

18. Williams, A.F., & Ferguson, S.A. (2004). Driver education renaissance? Injury Prevention: 10: 4-7.

19. Shell, D.F., Newman, I.M., Córdova-Cazar, A.L., & Heese, J.M. (2015). Driver education and teen crashes and trafc

violations in the rst two years of driving in a graduated licensing system. Accident Analysis & Prevention Volume

82: 45-52.

20. Lerner, N., Gill, M., Kellman, P.J., Burke, T., Older, R.M., & Scott-Parker, B. (2017). Development of a novice driver

training module to accelerate driver perceptual expertise. Washington, DC: AAA Foundation for Trafc Safety.

21. Fisher, D.L., Young, J., Zhang, L., Knodler, M., & Samuel, S. (2017). Accelerating teen driver learning: anywhere,

anytime training. Washington, DC: AAA Foundation for Trafc Safety.

22. Ford Driving Skills for Life. https://www.drivingskillsforlife.com/resources Accessed 11-25-2020.

PAGE 24 of 27

23. NHTSA Teen Driving webpage: https://www.nhtsa.gov/road-safety/teen-driving Accessed 9-17-2020

24. McCartt, A.T., Teoh, E.R., Fields, M., Braitman, K.A., & Hellinga, L.A. (2010). Graduated licensing laws and fatal

crashes of teenage drivers: A national study. Trafc Injury Prevention, 11: 240-248.

25. McCartt, A.T., Hellinga, L.A., & Haire, E.R. (2007). Age of licensure and monitoring teenagers’ driving: Survey of

parents of novice teenage drivers. Journal of Safety Research, 38: 697-706.

26. Farmer, C.M., Kirley, B.B., & McCartt, A.T. (2010). Effects of in-vehicle monitoring on the driving behavior of

teenagers. Journal of Safety Research, 41: 39-45.

27. Simons-Morton, B.G., Bingham, C.R., Claude Ouimet, M., Pradhan, A.K., Chen, R., Barretto, A., & Shope, J.T. (2013).

The effect on teenage risky driving of feedback from a safety monitoring system: A randomized controlled trial.

Journal of Adolescent Health [online article], 1-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23375825/

28. Carney, C., McGehee, D.V., Lee, J.D., Reyes, M.L., & Raby, M. (2010). Using an event-triggered video intervention

system to expand the supervised learning of newly licensed adolescent drivers. American Journal of Public

Health, 100:1101e6.

29. Ford Motor Company MyKey Feature. https://owner.ford.com/support/how-tos/technology/keys/how-to-use-my-

key.html Accessed 11-25-2020.

30. Life360. https://www.life360.com/features-driving-safety/ Accessed 11-25-2020

31. Hyundai Motor Company Blue Link® Connected Car Service. https://www.hyundaiusa.com/us/en/blue-link

Accessed 11-25-2020.

32. Bouncie. https://www.bouncie.com/ Accessed 11-25-2020.

33. State Farm Insurance Steer Clear® Safe Driver Discount. https://www.statefarm.com/insurance/auto/discounts/

steer-clear Accessed 11-25-2020

34. American Family Insurance Safe Driver Discount Program for Teens https://www.amfam.com/insurance/car/

teensafedriver Accessed 11-25-2020.

35. Fischer, P.S. (2013). Promoting parent involvement in teen driving. Washington, DC: Governors Highway Safety

Association.

36. Goodwin, A.H., Harrell, S., Foss, R., O’Brien, N.P., Kirley, B.B., & Wang, Y. (2018). Orientation sessions for parents of

young novice drivers: An assessment of U.S. programs and recommendations. Washington, DC: AAA Foundation

for Trafc Safety.

37. Cammisa, M.X., Williams, A.F., & Leaf, A.L. (1999). Vehicles driven by teenagers in four states. Journal of Safety

Research, 30: 25-30.

38. Klauer, S.G., Simons-Morton, B., Lee, S.E., Ouimet, M.C., Howard, E.H., & Dingus, T.A. (2011). Novice drivers’

exposure to know risk factors during the rst 18 months of licensure: The effect of vehicle ownership. Trafc

Injury Prevention, 12: 159-168.

39. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Center for Injury Research & Prevention (2009). Driving through the

eyes of teens a closer look, second in a series of teen driver safety issues. https://www.teendriversource.org/

Accessed 11-25-2020.

40. The Allstate Foundation (2015). Our journey to safer teen driving, 2015 data summary. Northbrook, IL. https://

www.allstate.com/resources/allstate/attachments/pdf/2015-chronic-taf-tsd-history.pdf Accessed 11-25-2020.

41. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parent-Teen Driving Agreement https://www.cdc.gov/

parentsarethekey/agreement/index.html Accessed 11-25-2020.

42. Varenhorst, B.B. (2004). Tapping the power of peer helping. Reclaiming children and youth. The Journal of

Strength-based Interventions 13(3): 130-133.

43. Fischer, P. (2019). Peer-to-peer teen trafc safety program guide (Report No. DOT HS 812 631). Washington, DC:

National Highway Trafc Safety Administration.

PAGE 25 of 27

Appendix 1

Teen Driver and Passenger Fatalities and Speeding-Related Fatalities by State,

2015–2019

State Total Teen Fatalities Speeding-Related Fatalities % Speeding-Related

Alabama 363 143 39%

Alaska 26 13 50%

Arizona 272 140 51%

Arkansas 172 58 34%

California 979 453 46%

Colorado 213 122 57%

Connecticut 72 39 54%

Delaware 30 15 50%

District of Columbia 5 4 80%

Florida 789 163 21%

Georgia 468 132 28%

Hawaii 30 25 83%

Idaho 96 25 26%

Illinois 335 197 59%

Indiana 320 127 40%

Iowa 154 43 28%

Kansas 167 88 53%

Kentucky 223 73 33%

Louisiana 237 76 32%

Maine 42 30 71%

Maryland 130 65 50%

Massachusetts 95 51 54%

Michigan 312 138 44%

Minnesota 120 43 36%

Mississippi 272 55 20%

Missouri 374 227 61%

Montana 86 38 44%

Nebraska 115 27 23%

Nevada 81 41 51%

New Hampshire 35 27 77%

New Jersey 116 58 50%

New Mexico 102 59 58%

New York 227

143 63%

North Carolina 436 214 49%

North Dakota 37 14 38%

Ohio 408 145 36%

Oklahoma 237 93 39%

Oregon 124 71 57%

Pennsylvania 344 234 68%

Rhode Island 18 12 67%

South Carolina 275 157 57%

South Dakota 57 26 46%

Tennessee 334 91 27%

Texas 1,212 534 44%

Utah 114 39 34%

Vermont 18 10 56%

Virginia 244 120 49%

Washington 163 71 44%

West Virginia 89 42 47%

Wisconsin 200 91 46%

Wyoming 51 28 55%

Total 11,419 4,930 43%

Source: FARS

PAGE 26 of 27

Appendix 2

Teen Driver and Passenger Fatalities and Speeding-Related Fatalities by State

Sorted by Number, 2015–2019

State Total Teen Deaths

Texas 1,212

California 979

Florida 789

Georgia 468

North Carolina 436

Ohio 408

Missouri 374

Alabama 363

Pennsylvania 344

Illinois 335

Tennessee 334

Indiana 320

Michigan 312

South Carolina 275

Arizona 272

Mississippi 272

Virginia 244

Louisiana 237

Oklahoma 237

New York 227

Kentucky 223

Colorado 213

Wisconsin 200

Arkansas 172

Kansas 167

Washington 163

Iowa 154

Maryland 130

Oregon 124

Minnesota 120

New Jersey 116

Nebraska 115

Utah 114

New Mexico 102

Idaho 96

Massachusetts 95

West Virginia 89

Montana 86

Nevada 81

Connecticut 72

South Dakota 57

Wyoming 51

Maine 42

North Dakota 37

New Hampshire 35

Delaware 30

Hawaii 30

Alaska 26

Rhode Island 18

Vermont 18

District of Columbia 5

Total 11,419

State Speeding-Related Teen Deaths

Texas 534

California 453

Pennsylvania 234

Missouri 227

North Carolina 214

Illinois 197

Florida 163

South Carolina 157

Ohio 145

Alabama 143

New York 143

Arizona 140

Michigan 138

Georgia 132

Indiana 127

Colorado 122

Virginia 120

Oklahoma 93

Tennessee 91

Wisconsin 91

Kansas 88

Louisiana 76

Kentucky 73

Oregon 71

Washington 71

Maryland 65

New Mexico 59

Arkansas 58

New Jersey 58

Mississippi 55

Massachusetts 51

Iowa 43

Minnesota 43

West Virginia 42

Nevada 41

Connecticut 39

Utah 39

Montana 38

Maine 30

Wyoming 28

Nebraska 27

New Hampshire 27

South Dakota 26

Hawaii 25

Idaho 25

Delaware 15

North Dakota 14

Alaska 13

Rhode Island 12

Vermont 10

District of Columbia 4

Total 4,930

The Governors Highway Safety Association (GHSA) is a nonprofit association representing the highway

safety offices of states, territories, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. GHSA provides leadership

and representation for the states and territories to improve traffic safety, influence national policy,

enhance program management and promote best practices. Its members are appointed by their Governors

to administer federal and state highway safety funds and implement state highway safety plans.

www.ghsa.org

@GHSAhq