The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S.

Department of Justice and prepared the following final report:

Document Title: Delivery and Evaluation of Sexual Assault

Forensic (SAFE) Training Programs

Author(s): Debra Patterson, Ph.D., Stella Resko, Ph.D.,

Jennifer Pierce-Weeks, RN, Rebecca Campbell,

Ph.D.

Document No.: 247081

Date Received: June 2014

Award Number: 2010-NE-BX-K260

This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice.

To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally-

funded grant report available electronically.

Opinions or points of view expressed are those

of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect

the official position or policies of the U.S.

Department of Justice.

Delivery and Evaluation of Sexual Assault Forensic (SAFE) Training Programs

2010-NE-BX-K260

FINAL REPORT

March 28, 2014

Principal Investigator: Debra Patterson, Ph.D., Assistant Professor

School of Social Work, Wayne State University

Detroit, MI 48202

Phone: (313) 577-5942

Email: [email protected]

Co-Investigator: Stella Resko, Ph.D., Assistant Professor

School of Social Work, Wayne State University

Detroit, MI 48202

Phone: (313) 577-4445

Email: [email protected]

Project Director: Jennifer Pierce-Weeks, RN, SANE-A, SANE-P

International Association of Forensic Nurses

6755 Business Parkway

Suite 303

Elkridge, MD 21075

Phone: (410) 626-7805 ext. 107

Consultant: Rebecca Campbell, Ph.D., Professor

Department of Psychology, Michigan State University

East Lansing, MI 48824-1116

Phone: (517) 432-8390

Email: [email protected]

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

ii

ABSTRACT

This study evaluated the effectiveness of the IAFN SAFE training that used an innovative blended

learning approach, which included a didactic portion online over a 12-week time period and a two-day

simulated clinical skills workshop. Healthcare clinicians (e.g., registered nurses) from across the United

States were enrolled in the training (N=198). We conducted an outcome evaluation using a mixed methods

approach to assess if the training was effective with training completion, knowledge attainment, and

knowledge retention three months post-training. Students completed a Web-based survey prior to the

training to examine three factors that may impact training completion: student characteristics, motivation,

and external barriers. To assess if there was a significant increase in the students’ knowledge, we utilized a

one-group pre-test post-test design where we assessed students’ knowledge attainment for all 12 online

modules. To examine students’ knowledge retention, students took an online post-training exam three

months following the training. Qualitative interviews were conducted with the clinical instructors to

understand their pedagogical approach and challenges to teaching clinical skills. In addition, we

interviewed students until we reached saturation of the major themes (N=64) about their post-training

experiences and struggles of applying their knowledge and skills into their practice.

Regarding training completion, the findings show that 79.3 percent of the enrolled students

completed the SAFE training. Utilizing hierarchical logistic regression, the study also found that students

were more likely to complete the training when they were interested in the training because of the two-day

clinical component. Students who work in rural communities were more likely to complete the training than

students from urban and suburban communities.

Regarding knowledge attainment, the results showed that the mean post-test scores were

significantly greater than the mean pre-test scores for all 12 online modules. On over 40% of the modules,

the students exhibited at least a 25% knowledge gain. Using a multiple linear regression model, we found

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

iii

that knowledge attainment was positively associated with students who have a reliable Internet connection,

students who were drawn to the training because it was no cost to them, and those with higher levels of

motivation. Lower knowledge gains were significantly related to students who reported more work/personal

barriers and those who were drawn to SAFE practice because they or someone close to them has personal

experience with sexual assault. Lower knowledge gain also was marginally linked with students who

reported less comfort with computers.

Regarding knowledge retention, the results indicate that students experienced a reduction of

knowledge from 77.92% at post-test to 68.83% at the follow-up exam with a 9.17% loss of knowledge.

Using multiple linear regression, the analysis found that knowledge retention was higher for students who

were drawn to the training because of the clinical training, and somewhat higher for students with more

nursing experience. Knowledge retention was significantly lower for those who have taken a prior online

course, and somewhat lower for students drawn to forensic nursing because of an experience with sexual

assault.

The qualitative interviews suggested that the clinical training helped clarify, broaden, or solidify the

content covered in the online modules. Most students identified utilizing many approaches they learned in

the training with their post-training patients. Some students indicated that they encountered challenges

since they began practicing as SAFEs such as feeling less prepared to provide care for some patient

populations (e.g., males), and having limited access to trained preceptors.

In conclusion, the evaluation’s overall assessment is that the IAFN SAFE training curriculum and

blended training model offers a strong foundation that can be built upon to meet the diverse learning needs

of clinicians across the country.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Report

1

I. Overview

9

II. Review of Relevant Literature

13

A. The Importance of Sexual Assault Forensic Nurse Examiners

13

B. Online Training as a Solution to SAFE Shortage

15

C. Limitations of Online Learning

17

D. Blended Learning: A Comprehensive Training Approach

19

III. The Current Research Project: Evaluation of the IAFN Training

21

A. Training Design and Implementation

21

B. Multi-Study Project Design: Concurrent Triangulation Mixed Methods Design

27

C. Quantitative Evaluation Aims

28

D. Qualitative Evaluation Aims

33

IV. Quantitative Evaluation Aims

35

Evaluation Question 1: What Factors Predict Training Completion/Attrition?

35

A. Methods

1. Research Design

35

2. Sampling

36

3. Procedures for Data Collection

39

4. Measures

41

5. Analytic Plan

43

B. Results

1. What Predicts Training Completion?

45

2. When did Attrition Occur?

49

Evaluation Question 2: Is There a Significant Increase in the Students’ Knowledge upon Completion

of the Training Modules?

52

A. Methods

1. Research Design

52

2. Sampling

52

3. Procedures for Data Collection

54

4. Measures

55

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

v

5. Analytic Plan

57

B. Results

1. Do Students’ Attain Knowledge?

58

2. What Predicts Knowledge Attainment?

60

Evaluation Question 3: Among those who Completed the Training, did the Participants Retain their

Knowledge 3 Months Post-Training?

63

A. Methods

1. Research Design

63

2. Sampling

64

3. Procedures for Data Collection

66

4. Measures

66

5. Analytic Plan

67

B. Results

1. Do Students Retain Knowledge of SAFE Practice?

68

2. What Predicts Knowledge Attainment Over Time?

69

V. Qualitative Evaluation Aims

73

A. Methods

1. Research Design

73

2. Sampling

74

3. Procedures for Data Collection

76

4. Measures

76

5. Analytic Plan

77

B. Results

Evaluation Question 4: How did the Clinical Training Contribute to Students’ Knowledge?

78

1. Instructors’ Pedagogical Approach.

79

2. Developing Sexual Assault Patient Care Skills

81

3. Developing Medical Forensic Exam Skills

87

4. Instructors’ Challenges and Recommendations

95

Evaluation Question 5: What were the Students’ Post-Training Experiences with Applying their

Knowledge?

99

1. Application of Skills with Post-Training Patients

99

2. Students’ Remaining Challenges with Patient Care

102

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

vi

3. Students’ Remaining Challenges with the Medical Forensic Exam

107

4. Students’ Experience and Needs when Encountering Delayed Practice

112

VII. Discussion of Findings

116

A. Summary of Cross-Study Findings and Implications

116

1. Findings from Evaluation Question #1: What factors predict training completion?

117

2. Findings from Evaluation Question #2: Is There a Significant Increase in the Students’

Knowledge upon Completion of the Training Modules?

124

3. Findings from Evaluation Question #3: Did the students retain knowledge?

129

4. Findings from Evaluation Question #4: How did the Clinical Training Contribute to

Students’ Knowledge?

133

5. Findings from Evaluation Question #5: What were the Students’ Post-Training

Experiences with Applying their Knowledge?

136

6. Evaluator Guidance for Incorporating Recommendations

143

B. Project Strengths, Limitations, and Implications for Future Research

150

C. Conclusions

154

VIII. References

156

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

vii

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Project Staff

175

Appendix B: Dissemination

177

Appendix C: Data Collection Instruments

178

Appendix D: Modules

230

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

viii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Creswell et al.’s (2003) Concurrent Triangulation Mixed Methods Design

28

Figure 2: Kaplan Meier Curve Illustrating Training Completion Over Time

51

Figure 3: Mean Increase in Knowledge from Pre-test to Post-test

60

Figure 4: Mean Increase in Knowledge from Pre-test to Post-test to three Month Follow-up

69

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

ix

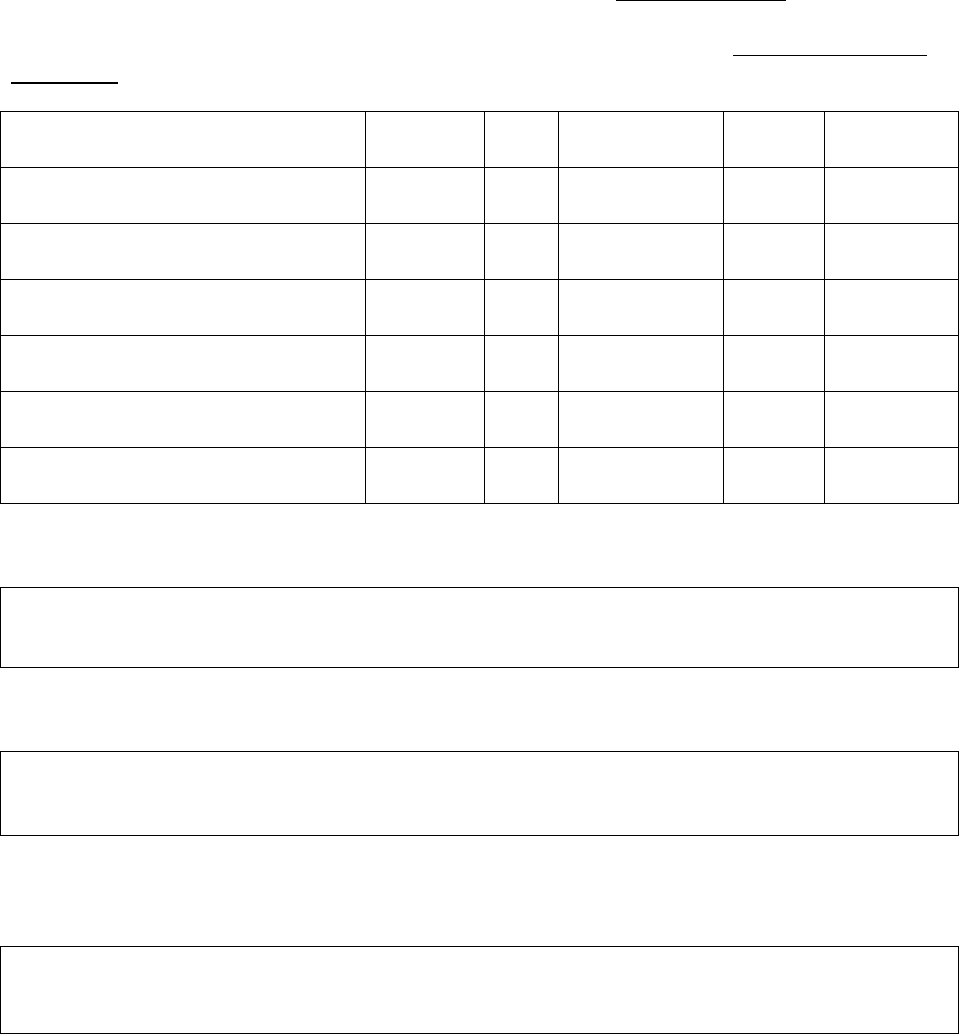

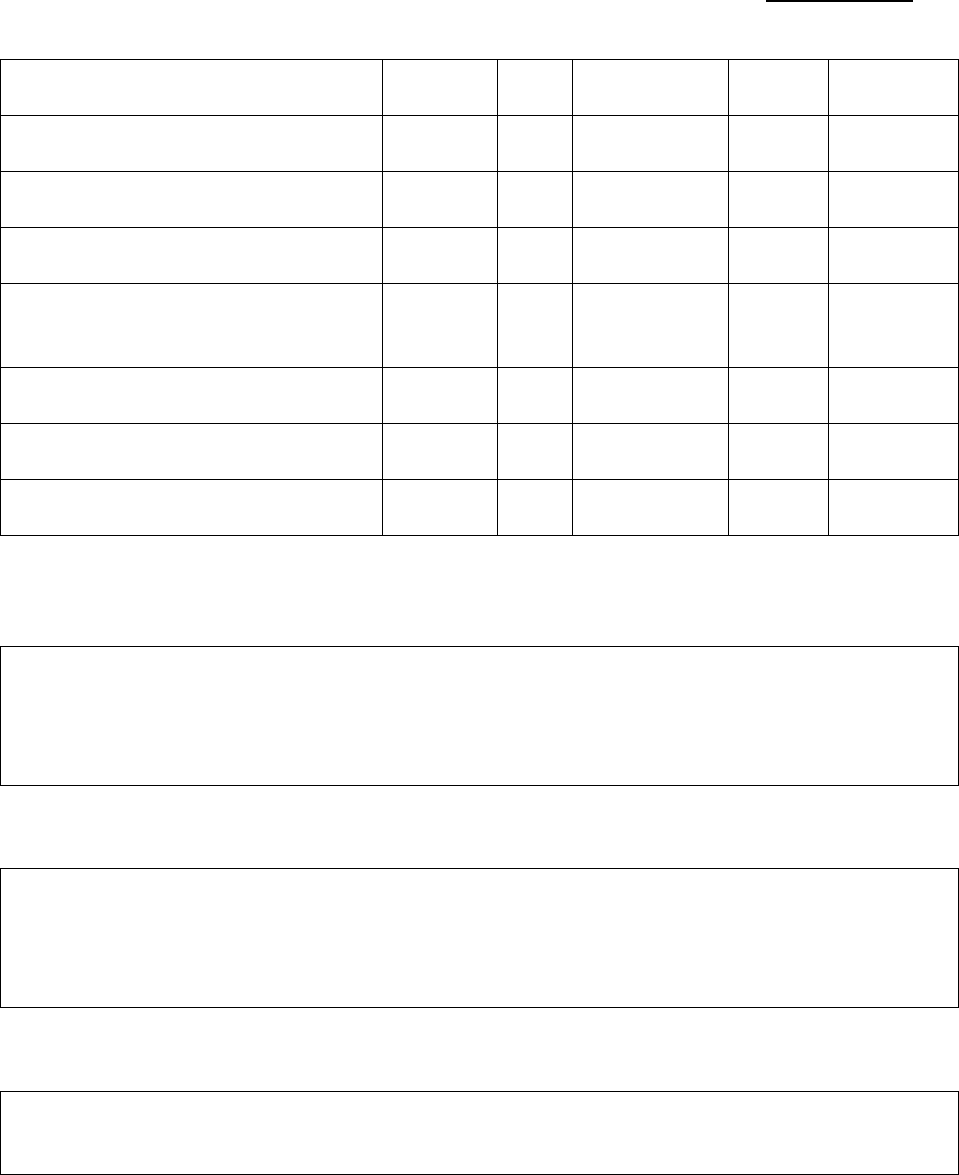

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Overview of the Evaluation Aims

29

Table 2 (Question 1): Students’ Descriptive Statistics

40

Table 3 (Question 1): Inter-correlations among Multivariate Predictor Variables for Training

Completion Analyses

44

Table 4 (Question 1): Bivariate Cross-tabulations and Chi-squared Tests Assessing the Relationship

between Training Completion and Study Variables

47

Table 5 (Question 1): Bivariate Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Training Completion

48

Table 6 (Question 1): Hierarchical Logistic Regression Predicting Training Completion

49

Table 7 (Question 1): Cox Proportional Hazards Model Predicting time to Attrition

50

Table 8 (Question 2): Students Descriptive Statistics

53

Table 9 (Question 2): Descriptive Statistics and t-test Results for Knowledge Attainment on Online

Modules

60

Table 10: Inter-correlations among Knowledge Attainment Multivariate Predictor Variables

61

Table 11 (Question 2): Bivariate Regression Analysis Predicting Knowledge Attainment

62

Table 12 (Question 2): Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Knowledge Attainment

63

Table 13 (Question 3): Descriptive statistics for Independent and Dependent Variables

65

Table 14 (Question 3): Inter-correlations among Knowledge Retention Multivariate Predictor

Variables

70

Table 15 (Question 3): Change in Knowledge Scores from Pre-test to Three Months Post-Training

71

Table 16 (Question 3): Bivariate Regression Analysis Predicting Knowledge Gains at Three Months

Post-Training

71

Table 17 (Question 3): Multiple Linear Regression Predicting Knowledge Retention

73

Table 18 (Question 4 & 5): Descriptive Statistics of Students Participation in the Qualitative

Interviews

75

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Sexual assault forensic examiner (SAFE) programs provide post-assault services to sexual assault

survivors that include medical forensic evidence collection, as well as patient-centered care to meet their

acute healthcare and emotional needs. Unfortunately, many victims do not have access to SAFE patient

care because there is a shortage of SAFE-trained clinicians across the United States. Limited access to

education has repeatedly been identified as a major contributor to the shortage of SAFE-trained clinicians,

especially in smaller communities. This project sought to address this shortage by delivering and evaluating

a comprehensive SAFE training developed by the International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN).

The IAFN SAFE training used an innovative blended learning approach: Students took a didactic

portion online over a 12-week time period and also attended a two-day clinical skills workshop. The 12-

week online structure allows students to learn the core content of SAFE practice without interfering with

their work schedule. The two-day clinical skills workshop was taught in a laboratory that simulates a clinical

setting with live models (gynecological teaching associate [GTA]) that allowed students to develop clinical

skills through repeated practice. To assess if the training was effective, we conducted an outcome

evaluation using a mixed methods approach, including quantitative pre-post training and qualitative

interviews with instructors and students.

The first evaluation question examined how many students completed the training and what

predicted training completion. This study used Web-based surveys that students (N=198) completed prior

to the training to examine three factors that may impact training completion and the timing of attrition:

student characteristics, motivation, and external barriers. The findings show that 79.3 percent of the

enrolled students completed the SAFE training, which is higher than completion rates for online courses in

general and substantially higher for free continuing education courses. Utilizing hierarchical logistic

regression, the study also found that students who were interested in the training because of the two-day

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

2

clinical component also were more likely to complete the training. Further, students who work in rural

communities were more likely to complete the training than students from urban and suburban

communities. In terms of when attrition occurred, we found that the instantaneous probability of attrition for

a participant who was motivated by the two-day clinical workshop was roughly a third of the probability for

those who were not interested in the two-day clinical workshop. The instantaneous probability of attrition for

those students that worked in a rural community was roughly a third of the probability for those who worked

in an urban or suburban community. The study also found that students who were interested in the training

because of its online nature were more likely to complete more of the training.

The second evaluation question examined if there was a significant increase in the students’

knowledge by utilizing a one-group pre-test post-test design where we assessed students’ knowledge

attainment for all 12 online modules. Students completed a weekly online pre-test before beginning each

training module and then a post-test upon completion of the module. The results showed that the mean

post-test scores were significantly greater than the mean pre-test scores for all 12 online modules. On over

40% of the modules, the students exhibited at least a 25% knowledge gain. The modules with high

knowledge gains included forensic science, ethics, and self-care (35.85%), photography (29.80%), medical

forensic history and physical (25.48%), evidence collection (25.63%), anogenital exam (23.93%), and the

justice system & testifying (20.75%). The modules with the lowest knowledge gains were medical

management module (15.86%), documentation (14.92%), program and operational issues (14.11%), and

patient centered, coordinated team approach (9.33%). We also examined the predictors of knowledge

attainment. Using a multiple linear regression model, we found that knowledge attainment was positively

associated with a reliable Internet connection, students who were drawn to the training because it was no

cost to them, and those students with higher levels of motivation. By contrast, lower knowledge gains were

significantly related to students who reported more work/personal barriers and those who were drawn to

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

3

SAFE practice because they or someone close to them has personal experience with sexual assault. Lower

knowledge gain also was marginally linked with students who reported less comfort with computers.

The third evaluation question sought to understand if the student retained their knowledge, which

was examined using an online post-training survey given to students three months following the training

and subsequently analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA. Our findings suggest that students

experienced a reduction of knowledge from 77.92% at post-test to 68.83% at the follow-up exam with a

9.17% loss of knowledge. Using multiple linear regression, the analysis found that knowledge retention was

somewhat higher for students with more nursing experience. Alternatively, students who have taken a prior

online course experienced significantly less knowledge retention. In addition, students who were drawn to

forensic nursing because of an experience with sexual assault was somewhat associated with less

retention of knowledge.

SAFE clinical skills are not commonly taught in a simulated laboratory setting. Thus, we wanted to

gain a more in-depth picture of the unique contributions of the clinical training with preparing clinicians for

SAFE practice. Therefore, the fourth evaluation question utilized a qualitative framework to understand the

instructors’ pedagogical approach to teaching clinical skills. In addition, we conducted qualitative interviews

to examine the students’ perceptions of the patient care and medical forensic exam skills gained from the

clinical component in the SAFE training, and how the clinical training contributed to their skill development.

Students who completed the entire training (i.e., online and clinical) were the target sample for the

qualitative interviews. We interviewed students until we reached saturation of the major themes (N=64).

The qualitative interviews also examined the fifth evaluation question: how students applied their gained

knowledge and skills into their practice with their post-training patients, along with any remaining struggles

that they encountered post-training. Furthermore, we explored the challenges experienced by a subset of

students following the training: those who are still waiting to examine their first patient (N=28 or 44% of all

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

4

students interviewed). In particular, we examined how students feel about not practicing, and if they

believed the delay will affect their abilities to practice as SAFEs.

The instructors indicated that their pedagogical approach began with creating an environment

conducive to learning by treating the students with respect and patience. The instructors began each skill

station by inquiring about the students’ clinical background to assess their learning needs. The instructors

also demonstrated components of SAFE practice, which provided students with a clear picture of the exam

process and to see the exam practiced correctly. While the students practiced different components of the

exam process with the GTAs, the instructors provided guidance and feedback. Instructors also suggested

that they promoted students’ clinical reasoning by having students’ articulate the rationale of their decisions

during the exam process. Together, the instructors believed that these different instructional methods

helped students to feel more confident with their skills by the end of the clinical training.

Because a patient-centered approach is important to the sexual assault patients’ wellbeing as well

as their participation in prosecution, we wanted to understand whether the students understood the concept

of patient-centered care. Prior to the training, several students said they had perceived the SAFE role only

as an evidence collector and identified forensic collection as their primary purpose with sexual assault

patients. By emphasizing that the well-being of the patient is paramount to SAFE practice, the training

helped students learn to see their SAFE role as an important part of the sexual assault patient’s healing. In

the qualitative interviews we asked students to describe different aspects of the SAFE role. The majority of

participants described some version of patient-centered care such as approaching sexual assault patients

with compassion and a non-judgmental attitude, and restoring a sense of control by providing them with

choices. While the entire training helped students understand the importance of patient-centered care, the

majority of students indicated that the clinical training played a stronger role in helping them learn how to

provide this model of care. The interviewed students explained that the hands-on practice and instructor

feedback were beneficial because they helped students conceptualize their approach with the patients’

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

5

comfort level in mind. Students reported that the realistic nature of the mock scenarios portrayed by the

GTAs was particularly beneficial to learning how to foster comfort during the exam and how to empower

sexual assault patients. By following the GTA’s cues (e.g. allowing or not allowing certain procedures

similar to how a patient may react), students were given practice on how to follow the needs of the patient,

which is a critical component of patient-centered care. In addition, observing the instructors demonstrate

the forensic exams and patient interactions helped students learn how to avoid re-traumatizing sexual

assault patients.

Another priority of the training was to help students attain the examination and evidence collection

skills needed to perform a competent sexual assault medical forensic examination. Overall, the majority of

students reported the clinical training substantially contributed to their knowledge and development of

medical forensic skills (e.g., history taking, conducting pelvic exams with a speculum). The GTAs’ realistic

portrayals of sexual assault patients were important in developing students’ skills, particularly with history

taking and pelvic speculum exams. During the pelvic exams, the instructors taught the students how to

identify abnormalities or injury using visualization and equipment. Students also learned about and were

able to practice photographing injuries and practice the Toluidine blue dye application and the Foley

catheter techniques. As a result of these instructional activities, the majority of students noted that they left

the training feeling confident enough to begin practicing.

For students who have had patients since the training, we asked them to describe a couple of post-

training cases and to describe how they approached or interacted with these patients. Students identified

utilizing many approaches they learned in the training to enhance their patients’ sense of safety, including

using a slower, gentler approach combined with non-threatening tone of voice and body language,

following the patients’ needs and allowing them to tell their story without interruption to build patient-

provider trust and rapport. Students also described offering their patients detailed explanations, validating

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

6

their experiences and avoid making any blaming or judgmental statements. Students reported this

approach appeared to help their sexual assault patients feel safe during the exam process.

We were also interested in understanding the quality of the students’ medical forensic evidence

documentation for exams with sexual assault patients following the training. Thus, the qualitative interviews

inquired if the students had received feedback from an experienced colleague or supervisor regarding their

documentation with sexual assault patients. Overall, we found that most students were not provided

feedback about their documentation from a supervisor or colleague. Some of the students who did receive

feedback were provided with brief remarks that they had done a good job with their documentation, while

others who do not have SAFEs in their institutions sought feedback from their department supervisors and

were told their documentation was detailed and thorough. A smaller number of students were provided with

feedback from trained SAFEs who indicated that the students’ documentation was of high quality.

The qualitative interviews also inquired about students’ remaining challenges they have

encountered since they began practicing as SAFEs. Although the clinical training included the practice of

patient interaction skills, many interviewed students expressed fear of re-traumatizing patients. Many

students also felt less prepared to provide care for male patients, patients with disabilities, and patients who

exhibit strong or absent emotional reactions. Students who practice in rural and low-resource SAFE

programs also continue to struggle with patient care due to their unique settings and challenges. For

example, some students reported they do not have local victim advocacy groups, which has resulted in

their role expanded to include the type of emotional support often provided by advocates. As a result, they

were less confident in their patient comfort skills. The students also identified several areas of struggle with

the medical forensic exam and documentation. Although the clinical training included several practice

opportunities, many students reported feeling unprepared for some aspects of the medical forensic exam

such as using the colposcope. Some students expressed a lack of confidence in the quality and accuracy

of their evidence collection because they have not received feedback from a SAFE in their institutions.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

7

Overall, the students believed that more practice opportunities during the clinical training would have let

them refine their skills.

Lastly, the interviews examined the challenges of those students who are still waiting to examine

their first patient. Many of the students who had not performed an exam remained committed to being a

SAFE. These students said they stayed motivated by keeping up with information and seeking out

educational opportunities. In addition, students found community groups (local IAFN chapter) to keep

abreast of SAFE topics while connecting to other SAFEs. Several students said they would be able to

perform an exam because the skills they learned in the training would be quickly remembered and

incorporated into their practice. However, several students said they would approach their first exam with

less confidence than they would had they performed their first exam immediately following the training.

Despite this decreased confidence, these students still expressed their continued interest in pursuing SAFE

work.

In conclusion, the evaluation identified many successes of the training. The majority of students

completed the training. Students exhibited high knowledge gains in the online modules pertaining to

forensic science, ethics, and self-care; photography; medical forensic history and physical; evidence

collection; anogenital exam; and justice system and testifying. Further, students experienced a fairly high

level of knowledge retention in comparison to the rates reported in prior research. As common with the

initial development of a training, the evaluation identified many challenges and recommendations. Students

experienced lower knowledge gains in multiple online modules, including those focusing on medical

management; documentation, program and operational issues; and patient-centered, coordinated team

approach. Several students indicated that these lengthy modules could be improved by breaking them into

subsections, as well as adding homework assignments that would allow instructors to provide formative

feedback on student progress. Many students in the qualitative interviews indicated that the clinical training

helped clarify, broaden, or solidify the content covered in the online modules. Finally, the evaluation

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

8

identified distinct learning needs of students with less healthcare experience and from rural communities,

which will require some modifications to the training. For example, these students believed that additional

practice time during the clinical training, as well as post-training supports (e.g. refresher training), would

have helped them feel more prepared to practice as SAFEs. These challenges and recommendations

notwithstanding, the evaluation’s overall assessment is that the IAFN developed a comprehensive SAFE

training curriculum that has the potential to meet the diverse learning needs of clinicians across the country.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

9

I. Overview

National epidemiological data suggest that at least 17% of women will be sexually assaulted in

their adult lifetimes (Tjaden, & Thoennes, 1998, 2006); however, most victims/survivors do not report to law

enforcement (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2007). Overall, approximately 18% of reported sexual assaults

are prosecuted (Campbell, 2008a; Spohn, 2008). When rape victims/survivors seek professional help after

an assault, they are most likely to be directed to the medical system, specifically hospital emergency

departments (ED) (Resnick et al, 2000). Over the years, both researchers and rape victim advocates have

noted numerous problems with this ED-based approach to post-assault health care and forensic collection

(Martin, 2005; Campbell & Martin, 2001; Campbell & Bybee, 1997). Many ED physicians are reluctant to

perform the rape exam (Martin, 2005), and most lack training specifically in forensic evidence collection

procedures (Littel, 2001). As a result, many rape kits collected by ED doctors are done incorrectly and/or

incompletely (Littel, 2001; Sievers, Murphy, & Miller, 2003). Additionally, emerging research indicates that

many rape victims are retraumatized by post-assault ED exams, which often leave them feeling more

depressed, anxious, blamed, and reluctant to seek further help (Campbell et al., 2001; Campbell et al.,

1999; Campbell & Raja, 1999; Campbell, 2005). These negative experiences have the unintended effect of

decreasing victims’ willingness to participate in law enforcement investigations and legal prosecution

(Campbell, 1998).

To address these problems, communities have implemented Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner

(SAFE) Programs

1

. These programs employ specially trained clinicians, usually nurses (rather than hospital

emergency department physicians) to provide comprehensive psychological, medical, and forensic services

for sexual assault victims (DOJ, 2004, 2006). SAFE programs can be a vital resource to victims as well as

the legal community, with prior research suggesting that these programs have improved the response

1

For purposes of this report, we will primarily refer to the medical personnel as SAFEs to be inclusive of all medical disciplines.

In addition, we will use the term “sexual assault” to reflect the broader range of contact and non-contact sexual offenses

including rape (see Koss & Achilles, 2008).

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

10

towards victims by meeting their acute healthcare and emotional needs, as well as the quality of medical

forensic evidence collection and documentation (Cabral, Campbell, & Patterson, 2011; Derhammer,

Lucente, Reed, & Young, 2000; Ledray & Simmelink, 1997; Sievers et al., 2003). This fundamental shift

has had a positive impact on the prosecution of rape cases (Campbell, Patterson, & Bybee, 2012; Crandall

& Helitzer, 2003). Therefore, it is critical that patients have access to SAFE clinicians, as they provide a

bridge between healthcare and legal systems.

Unfortunately, many victims do not have access to SAFE patient care because there is a shortage

of SAFE-trained clinicians across the United States. Limited access to training has repeatedly been

identified as a major contributor to the shortage of SAFE-trained clinicians, especially in smaller

communities. As recently as December 2009, IAFN’s SAFEta Project Coordinator noted that in the course

of delivering specific technical assistance around the National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic

Examinations of Adults/Adolescents, many rural and tribal areas are still struggling to find and provide

SAFE training for healthcare providers (K. Day, personal communication, May 1, 2010). The structure of

SAFE courses also may limit accessibility to training for some clinicians. Per the IAFN’s Sexual Assault

Nurse Examiner Educational Guidelines, this included 40 hours of didactic education followed by

recommended clinical activities that complement the didactic content. Traditionally, SAFE courses are

taught in-person over the course of one week, with students fulfilling their clinical hours following the

didactic education by performing pelvic exams at healthcare clinics with patients who are seeking routine

gynecological care. This is followed by the students practicing SAFE-related skills with sexual assault

patients under the supervision of a preceptor. The traditional one-week didactic course structure requires

training participants to incorporate training schedules into their personal and professional lives. Often, this

means that students are using vacation time and are paying for travel expenses out of pocket, which may

not be possible for all interested clinicians. Even when clinicians are able to complete the didactic training,

they may experience difficulty with obtaining necessary post-didactic clinical hours, which may prevent

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

11

trained clinicians from practicing as SAFEs. Attrition may be problematic as many trainers estimate that

roughly half of those who complete the training will actually practice as a forensic examiner

2

.

The purpose of this current project was to develop and evaluate a comprehensive sexual assault

medical-forensic examination training program that would reduce students’ barriers to accessing and

completing SAFE training. This project enabled IAFN to create and implement standardized, accessible

SAFE training on a national level by utilizing a blended training structure. Blended training incorporates

online and face-to-face modalities within a training by placing the didactic component of training online

while the face-to-face component focuses on skill building. The SAFE training taught a patient-centered

approach, the examination and evidence collection skills needed to perform a competent sexual assault

medical-forensic examination, and to impart knowledge of the criminal justice process to enable effective

courtroom testimony.

Most SAFE training is conducted in a classroom setting, during a one-week timeframe with a series

of PowerPoint presentations and minimal hands-on activities. However, spacing the content over a longer

timeframe rather than a truncated amount of time can improve knowledge retention (Bell et al., 2008). In

addition, an active learning approach has been shown to be substantially effective for learning clinical skills

(Stefanski & Rossler, 2009). The IAFN SAFE blended training was designed so that students took the

didactic portion online over a twelve-week time period through a series of modules. The bulk of the didactic

course was completed on the students’ own schedules, which increases accessibility to high-quality training

for rural and remote clinicians, and those who cannot leave their employment for a week-long training.

Obtaining clinical education has been a challenge for many clinicians who have completed the didactic

portion of SAFE training. Many communities have no experienced SAFEs with whom clinicians can train, or

2

Anecdotal conversations with trainers including Susan Chasson, Jenifer Markowitz, Jennifer Pierce Weeks, Kim Day and Carey

Goryl, also based on the number of SANE/SAFE courses listed in IAFN’s training calendar averaged annually and the number of

memberships to IAFN generated from these classes.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

12

simply have too few patients to obtain clinical competency. The IAFN training addressed these barriers by

providing a face-to-face two-day clinical skills workshop following the didactic series. The workshop

provided students with the opportunity to gain critical clinical skills as students were provided hands-on

experience through multiple case scenarios with gynecologic teaching associates (GTAs). Moreover, the

workshop provided an opportunity for participants to form a valuable network of mentors and peers to

provide support and assistance. The blended course was offered three times to allow for a manageable

course size to ensure that students’ learning needs were met. This course was available to clinicians at no

cost.

To assess if the training was effective, an outcome evaluation using a mixed methods approach

was conducted. First, the evaluation examined training completion, including the percentage of students

who completed the training and the factors that contributed to their completion. Second, the evaluation

assessed whether students attained knowledge through pre-test/post-tests and the factors that contributed

to knowledge attainment. We also conducted qualitative interviews with students to understand how the

clinical training contributed to their knowledge of patient and medical forensic exam skills. In addition,

qualitative interviews were conducted with the instructors to understand how they approached the clinical

training, challenges that they encountered during the training, and recommendations for future trainings.

Third, students’ retention of their knowledge was evaluated through a post-training exam approximately

three months following the training. Furthermore, qualitative interviews were conducted with students to

explore how the students applied their gained knowledge and skills into their practice following the training.

In addition, the interviews explored any challenges that the students encountered post-training, and their

recommendations for future trainings.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

13

II. Review of Relevant Literature

A. The Importance of Sexual Assault Forensic Examiners

Sexual Assault Forensic Nurses Examiner (SANE/SAFE) Programs emerged in the 1970s and now

number close to 600 programs throughout the United States (IAFN, 2013). Examiners in these programs

provide extensive psychological, medical, and forensic services for rape victims. The goal of SAFE

programs is to provide supportive care to victims while improving prosecution rates. SAFE programs strive

to improve prosecution by providing: 1) better-quality medical forensic evidence collection by specially

trained healthcare clinicians; 2) case consultation for law enforcement officials to increase their

understanding of medical evidence findings; and 3) expert witness testimony (Littel, 2001).

Research has found that SAFE programs can contribute to increased reporting and prosecution

rates for sexual assault cases (Campbell, Patterson, & Bybee, 2012). Campbell and colleagues (2008)

identified that SAFE practice can positively impact criminal justice outcomes through increased

engagement of sexual assault patients in the investigative and prosecution process (Patterson & Campbell,

2010). In particular, SAFEs help their patients begin the process of reinstating control over their bodies and

lives by not pressuring them to report to law enforcement. They emphasize that it is the victims’ choice and

SAFEs are there to care for them whatever they decide (Campbell, Greeson, & Patterson, 2011; Campbell,

Patterson, Adams, Diegel, & Coats, 2008). This attention to helping survivors heal indirectly affects their

willingness to participate in legal prosecution. When survivors are not as traumatized, they are more willing

and capable of participating in the prosecution process. In addition, survivors often have questions about

the medical forensic exam and the process of criminal prosecution. When forensic examiners provide

patients with this information, victims have more hope for and confidence about their legal cases, which

also indirectly contributes to increased victim participation (Campbell, Patterson, Bybee, & Dworkin, 2009).

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

14

Competent medical/forensic care can also provide victims with greater confidence in the criminal

justice system as a result of effective collaboration between SAFEs and colleagues in law enforcement and

prosecution (Campbell, Patterson, & Cabral, 2010). Clinical education on the medical forensic exam

process helps cultivate and enhance clinicians’ skills as expert witnesses and teaches effective trial

preparation in collaboration with prosecutors.

Numerous case studies suggest that SANEs are a vital resource to police and prosecutors (see

Campbell, Patterson, & Lichty, 2005 for a review). SAFE programs give law enforcement personnel and

prosecutors state-of-the-art forensic evidence to document crimes of sexual assault. The evidence

collected by the SAFE is typically sent to the state crime lab for analysis and the results are forwarded to

the prosecutor’s office. For example, research has shown that medical forensic evidence (MFE)

significantly predicts increased case progression, even after accounting for other characteristics that

traditionally have stunted case progression (e.g., use of alcohol). As such, the quality of the documentation

is paramount to successful legal outcomes. High-quality documentation also increases the likelihood that

law enforcement and prosecutors will utilize this documentation in their work. Detailed documentation may

suggest investigational leads that law enforcement could pursue to further develop a case. Prosecutors are

more inclined to charge cases when quality MFE documentation exists and often utilize this documentation

as a tool for plea bargaining when appropriate (Campbell et al., 2009). Two NIJ-funded, quasi-experimental

pre-post studies found that prosecution rates significantly increased after the implementation of SAFE

programs (Campbell, Bybee, Ford, Patterson, & Ferrell, 2009; Crandall & Helitzer, 2003). These results

suggest SANE programs may be effective in addressing the under-prosecution of sexual assault.

Overall, the emerging literature has suggested that SAFE programs play a critical role in improving

the response towards sexual assault victims, as well as prosecution rates. Despite the importance of SAFE

programs, there is a shortage of trained SAFEs in many communities often due to lack of accessible

training. This may be particularly true for less populated, geographically dispersed areas such as smaller

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

15

cities, rural communities, and tribal lands where access to training has been limited (Roberts, Brannan, &

White, 2005). In addition, remote/rural locations often struggle with competency due to limited or

nonexistent local expertise and low patient volume. Consequently, many victims across the United States

do not have access to quality patient care and expert medical forensic evidence collection following a

sexual assault.

B. Online Training as a Solution to SAFE Shortage

Online training may be a viable solution to increasing the number of trained SAFEs. Online training

has gained popularity and acceptance as a legitimate educational forum for providing high quality

healthcare training (Allen, & Seaman, 2010; Miller, Devaney, Kelly, & Kuehn, 2008; Ruiz, Mintzer, &

Leipzig, 2006). In addition, online training addresses a common barrier for many clinicians – family and

work responsibilities – of participating in professional training (Gormley, Costanzo, Lewis, Slone, & Savage,

2012). Online training is flexible and convenient and thus, time and costs associated with travel are

eliminated (Johnston, 2007). As such, online training increases accessibility to those living in remote areas

or those would have had to take time off from their jobs for training to attend a week-long classroom

training (Welsh, Wanberg, Brown, & Simmering, 2003; Pratt, 2002). Additionally, online training increases

the opportunity for students to have national experts serve as their instructors (Miller, Devaney, Kelly, &

Kuehn, 2008).

The extant literature has examined satisfaction and effectiveness with online learning among

practicing and student nurses, physicians, and other healthcare professionals. This literature suggests that

many healthcare students have characterized their online learning experience as primarily satisfactory

(Atack, 2003; Atack & Rankin, 2001; Bloom & Hough, 2003). In particular, students appreciate the flexibility

in scheduling and reduced travel, as well as the self-directed and self-pacing nature of online learning

(Roberts, Brannan, & White, 2005; Salyers, 2005). Students believed that this reduction in travel time could

be devoted to learning course concepts (Bello et al., 2005). Learners also expressed satisfaction with

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

16

online courses when they were provided with opportunity to share information, ask questions, and receive

feedback from other students and the instructor (Atack, Rankin, & Then, 2005; Johnson, Hornik, & Salas,

2008). Additionally, students find online training satisfactory because it provides multiple types of activities

for learning, such as recorded lectures, case studies, links to articles, patient interviews, and interactive

videos (Atack , Rankin, & Then, 2005; Zhang, Zhou, Briggs, & Nunamaker, 2006).

In terms of effectiveness, the overwhelming majority of studies have found online learning to be

effective in increasing knowledge across a wide variety of topics and healthcare learners (e.g., registered

nurses, medical and nursing students, physicians) (Cook et al., 2008; Smith, Silva, Covington, & Joiner,

2013; Stone, Barber, & Potter, 2005; US Department of Education, 2010). Furthermore, research has

suggested that online learning is effective for improving healthcare professional’s competencies, which

yields better patient care (Atack, Rankin, & Then, 2005; Schneiderman, Corbridge, & Zerwic, 2009).There

have been fewer studies examining knowledge retention following the training. These studies found the

degree of knowledge retention has been correlated positively to course satisfaction, student motivation, and

the amount of time spent with the online material (Metcalf, Tanner, & Buchanan, 2010; Naidr et al, 2004). In

addition, opportunity to discuss course content among students and with the instructor on discussions

boards has been linked to successful learning outcomes (Johnston, 2007; Means, Toyama, Murphy, Bakia,

& Jones, 2010).

Many studies have compared the effectiveness of online learning to the traditional face-to-face

classroom setting among healthcare learners, and found them to be equally effective with attaining

knowledge (Bello et al., 2005; Buckley, 2003; Day, Smith, & Muma, 2006; Hugenholtz, Croon, Smits, van

Dijk, & Nieuwenhuijsen, 2008; Jeffries et al., 2003; Leasure et al., 2000; Pratt, 2002; Salyers, 2005;

Walters, Raymont, Galea, & Wheeler, 2012; Woo & Kimmick, 2000). Although the majority of studies

suggest that online learning is neither inherently superior nor inferior to face-to-face learning (Cook et al.,

2008), a few studies have suggested that online learning produces modestly better learning outcomes

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

17

(Bandla et al., 2012; Means, Toyama, Murphy, Bakia, & Jones, 2010). Alternatively, a couple of studies

found mixed results with the online participants yielding higher scores than face-to-face learners on some

topics taught in the course but lower scores on other topics (Jang, Hwang, Park, Kim, & Kim, 2005;

Johnston, 2008). There is a dearth of research examining knowledge retention between these two learning

modalities, but a couple of studies tracked their participants’ pass rates for national certification exams and

found mixed results. For example, Hansen-Suchy (2011) found no significant differences in certification

exam scores for medical laboratory technicians and first time pass rates between online and face-to-face

learners. However, Johnston (2008) found that the exam scores for the patient care section of the

American Registry of Radiologic Technologists certification exam were higher for face-to-face learners than

for those online learners. Taken together, this research suggests that online and face-to-face modalities

produce similar learning outcomes in general, but each modality may provide learning conditions favorable

for particular topics.

C. Limitations of Online Learning

Although effective, online learning has its challenges. While research has suggested that the

majority of healthcare students find online learning satisfactory, some students may find this learning

modality less satisfying or more challenging. For example, students who have less comfort and experience

with computers would have difficulty maneuvering an online learning management system and would

require more technological guidance (Atack, Rankin, & Then, 2005). In addition, students may misperceive

online courses as easier and underestimate the amount of time needed to maintain the course expectations

(Johnston, 2007). Some students prefer the face-to-face learning experience because it offers opportunity

for direct interaction and opportunity to receive answers to their questions in real-time (Bandla et al, 2012;

Day, Smith, & Muma, 2006). Therefore, some students may experience feelings of isolation in an online

course, particularly if there is limited opportunity for students to interact with each other or receive feedback

from the instructor (Atack & Rankin, 2001; Johnston, 2007).

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

18

Another common challenge is that fewer students complete online courses. Research has

compared attrition rates between online and face-to-face settings, and found that online courses tend to

have higher attrition rates, often exceeding the classroom by 10%-20% (American Association of Colleges

of Nursing, 2010; Gilmore & Lyons, 2012). Attrition can be particularly challenging for free continuing

education courses because students may not be serious about completing the course (Stone, Barber, &

Potter, 2005). For example, Walters and colleagues (2012) reported a 53.1% completion rate for a

continuing education medical course. Gyorki et al. (2013) found a similar completion rate of 55.3% of those

who began the continuing education course but also noted an even earlier risk of attrition. Of those who

enrolled in the training, only three-quarters actually started the course.

Why are attrition rates higher for online courses? While student demographics and course

satisfaction have not been found to influence attrition substantially, lack of time, low motivation, and job

changes appear to contribute to attrition rates (Martinez, 2003; McMahon, 2013; Patterson & McFadden,

2009). For example, students who had more family responsibilities or worked full-time were more likely to

drop a course (Angelino, Williams, & Natvig, 2007; Willging & Johnson, 2009). Furthermore, students were

less likely to complete a course when they experienced personal and family problems such as health

concerns or death of a family member (Perry, Boman, Care, Edwards, & Park, 2008). Further, students with

less motivation may drop an online course because it requires more self-discipline and self-pacing than

traditional courses (Atack, 2003). Additionally, students may not complete a course if they realize that the

training no longer fits with their career aspirations (Perry, Boman, Care, Edwards, & Park, 2008).

Finally, clinical skills are complex and difficult to teach so it is unclear if online courses are

conducive for learning these complex skills (Rowe, Frantz, & Bozalek, 2012). Research has suggested that

online healthcare learners have additional needs that are typically addressed in the traditional face-to-face

classrooms, such as time to practice new skills (Atack & Rankin, 2001; Gilmore & Lyons, 2012). Blended

learning (also termed “hybrid”) may be a solution to address some of the challenges of online learning by

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

19

combining the online modality with the face-to-face setting (Means et al., 2010). This approach allows

students to gain new knowledge online while practicing new skills in the face-to-face setting.

D. Blended Learning: A Comprehensive Training Approach

Blended learning is a fairly new training approach in healthcare (Makhdoom, Khoshhal, Algaidi,

Heissam, & Zolaly, 2013), but it might be particularly advantageous because students receive the benefits

of both the online and face-to-face learning modalities. For example, most blended learning models places

the primary content in the online component, which allows healthcare students to learn the core content at

a flexible pace, reducing the common training barriers of work and family responsibilities (Gormley,

Costanzo, Lewis, Slone, & Savage, 2012). When students gain a solid knowledge of the content online, it

optimizes the time allotted for students to practice new skills during the face-to-face component (Bradley et

al., 2007; Lehmann, Bosse, & Huwendiek, 2010). Additionally, the face-to-face interaction provides

opportunity for students to interact with other students and ask questions of the instructor while they are

practicing skills (Gormley, Costanzo, Lewis, Slone, & Savage, 2012). Together, the blended learning model

provides a richer learning experience that meets the varied needs of students (Wild, Griggs, & Downing,

2002). Consequently, healthcare students who participate in blended learning tend to report feeling more

motivated and satisfied than those in an online or face-to-face only training (Bradley et al., 2007; Sung,

Kwon, & Ryu, 2008).

There have been few studies examining the effectiveness of blended learning for clinical

healthcare training (Rowe, Frantz, & Bozalek, 2012), but the existing research suggests favorable

outcomes. In a systematic review, Rowe and colleagues (2012) report that blended learning can enhance

clinical competencies such as history taking, performing examinations, documentation, and clinical

reasoning. Other studies have examined the effectiveness of blended learning to the traditional face-to-face

setting, and found that students who participated in blended training had significantly higher mean scores

(Makhdoom, Khoshhal, Algaidi, Heissam, & Zolaly, 2013; Means, Toyama, Murphy, Bakia, & Jones, 2010;

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

20

Stewart, Inglis, Jardine, Koorts, & Davies, 2013; Pereira et al., 2007; Sung, Kwon, & Ryu, 2008). Only one

study has examined knowledge retention of healthcare students who participated in a blended training, and

they found that students retained their knowledge two to four weeks following the training (Karamizadeh,

Zarifsanayei, Faghihi, Mohammadi, & Habibi, 2012). Blended learning may yield stronger effects because

students receive additional learning time and materials within two learning contexts, which increases the

likelihood of meeting the diverse learning needs of students (Means et al, 2010; Stewart, Inglis, Jardine,

Koorts, & Davies, 2013). Furthermore, the classroom learning likely reinforces the content learned online,

which can facilitate knowledge retention (Bradley et al., 2007).

Overall, blended learning addresses many of the common barriers to accessible training by placing

most of the students’ learning time online, but it also addresses some of the challenges with exclusive

learning online. As such, blended learning may be a viable option for increasing the accessibility of SAFE

training while advancing the students’ clinical skills. A clinical component of the training allows students to

have earlier exposure to gaining clinical skills essential for SAFE practice, which may be particularly

important for new SAFEs working in geographically dispersed communities where there are low volumes of

sexual assault patients. In this case, students might experience a delay in applying their new knowledge

and skills while they are waiting for their first sexual assault patient. In addition, there is a shortage of

nursing preceptors in these areas, including preceptors who have training as SAFEs (Elfrink, Kirkpatrick,

Nininger, & Schubert, 2010). This shortage may prevent new SAFES from receiving adequate clinical

experience to gain core competencies. Thus, a clinical component of a SAFE training may circumvent

these issues by helping students develop their foundational clinical skills. However, there is a dearth of

research on whether a blended training model is effective in developing the knowledge and skills essential

for competent SAFE practice.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

21

III. The Current Research Project: Evaluation of the IAFN SAFE Blended Training

A. Training Design and Implementation

1. Training Development. In accordance with best practices for online learning, the training was

developed through a peer review process (Ruiz, Mintzer, & Leipzig, 2006). In 2011, two focus groups were

convened in order to develop the online curriculum for the Sexual Assault Forensic Examiner

adult/adolescent training. The first focus group was comprised of community-based advocates, detectives,

prosecutors and crime lab analysts from across the United States. The second focus group was comprised

of SANE-A board certified Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners, advanced practice nurses and physicians from

across the United States. Under the facilitation of the Project Director and the assistance of a curriculum

specialist, the focus groups reviewed existing curriculum in conjunction with the International Association of

Forensic Nurses Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner Education Guidelines. The curriculum was edited to the

approval of both groups and formatted utilizing the American Nurses Credentialing Center format for

continuing education activities, and content expert presenters for specific topics were identified.

The full online curriculum was separated into twelve distinct modules. Current bibliographic

references for each module were compiled along with participant handout material that would be utilized in

the presentation material. Content experts developed specific PowerPoints for their presentations based on

the agreed upon curriculum, and created an audio recording of their lectures. This allowed students to view

PowerPoint slides while hearing the lecture. The project director in conjunction with the curriculum

consultant developed pre-test and post-test questions for each individual module to be completed by

course participants within the Learning Management System.

All finalized recorded content was transcribed and formatted into Shareable Content Object

Reference Model (SCORM) for the web-based e-learning system. Content was then loaded and launched

from the Digital Ignite Learning Management System. The Digital Ignite SCORM compliant Learning

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

22

Management System (LMS) housed the online training and discussions during course delivery. Each

participant's progress was tracked by the LMS, and participation was tracked online by the Project Director.

Each online module included a pre-test and post-test for participants, tracking their before and after

knowledge of content. The LMS was able to support a variety of learning formats including Flash, streaming

video and audio narrations, and various reading assignments and materials hosted internally. The

evaluations of each module and the overall course were also housed and tracked internally within the LMS.

The clinical skills lab curriculum was developed from a previously implemented clinical skills

training launched on the East Coast over 10 years ago, and was based on a precepted competency

assessment of SAFE-trained nurses working in rural communities with low volumes of sexual assault

patients. This existing one-day curriculum was expanded to a curriculum that would allow for one day of

training, including hands-on demonstration with live simulated patients, in the technical aspects of the

examination (evidence collection, speculum use, culture collection, Foley catheter, Toluidine blue dye and

colposcope use, photography and history taking). Day one was followed by a second day of training where

the precepted students performed mock complete sexual assault medical forensic examinations using live

simulated patients while being taught and evaluated by preceptors. The live clinical skills lab curriculum

was reviewed and revised by the medical expert focus group in keeping with the necessary clinical skills

acquisition expected of practicing Sexual Assault Forensic Examiners, whether they are registered nurses

or advanced practice providers, according to the IAFN SANE Education Guidelines.

2. Quality Assurance. During the in-person focus groups, nationally recognized experts from the

fields of advocacy, law enforcement, prosecution, medical and criminalistics (forensic science) gathered to

review, revise and approve the online and live clinical skills curriculum in keeping with the IAFN SANE

Education Guidelines and national protocols. The Project Director and curriculum expert outlined the

objectives in keeping with Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, including the six categories of

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

23

knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation. The content was then outlined

and sequenced with timeframes for completion, and all objectives were evaluated by participants.

3. Didactic Online Content. SANE training can look very different from one state to another, and

while the IAFN Education Guidelines are specific with regard to content that must be covered, how that

content is covered across jurisdictions is less clear. It was necessary that the content be generalizable

across jurisdictions, and that the students be able to pull out state- or territory-specific information

whenever necessary. Additionally, there are considerable differences between delivering an online versus

live audience training. It was important to utilize instructors that understood the absence of the live student,

and were willing and able to engage with students in different formats (i.e. email, online discussions) to

address any content questions that arose.

Therefore, Didactic Content Instructors were chosen across a wide geographic distribution based

on their extensive work in their area of expertise (SANE Practice, advocacy, investigation, criminalistics

[forensic science], prosecution) and for their known training ability. Because students would be attending

from all over the country, a mix of instructors was chosen from around the United States to represent the

larger country rather than a specific location. Many of the chosen instructors were from the original

curriculum development focus groups. Below is a summary of the content covered in the modules.

a) SAFE training introduction. The participants were introduced to the online learning management

system, logging in, how to negotiate completion of the pre-tests and post-tests, managing both the content

and handout materials, and troubleshooting technology issues. This module also introduced participants to

the SAFE field, including its history and the role of the SAFE.

b) Module I: Dynamics. The participants were given a basic introduction to the prevalence,

incidence and misconceptions that surround rape, sexual assault and abuse in the adult and adolescent

populations. An overview of the varying needs of specific patient populations (e.g., males, military, prison

population, LGBTQ, disabilities, etc.) were covered during this module.

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

24

c) Module II: Forensic science, ethics and self-care. This module provided the fundamental basis

for the work as a sexual assault examiner, including evidence-based practice, the role of the sexual assault

examiner in the care of the patient who has experienced sexual violence, and the ethical implications of

practice. Additionally, recognizing the impact of trauma on the health and well-being of the examiner is

paramount to ensuring the ability to continue providing services. This module provided a baseline

understanding of what impact compassion fatigue can have, and how a plan may be devised to counter or

address that impact.

d) Module III: Patient-centered, coordinated team approach. While the focus of this training is on

the healthcare response to sexual assault and its implications on the patient’s long-term health and well-

being, it is only one component of a larger response with multiple service providers. Each responder to

sexual assault plays a different role, and it is best practice to assure that this approach is coordinated and

streamlined as much as possible to provide a comprehensive, holistic, healing process for the patient. This

module of the training explained the roles of the various responders to sexual assault. Striving to have a

coordinated, multidisciplinary team approach may be another area where the examiner is expected to

provide leadership at the community level. Recognition of the roles of different responders is an important

concept for the examiner.

e) Module IV: History and physical. The medical forensic history is one of the fundamental

components of the examination. It is from that history that important details of the assault may emerge

(e.g., relationship between victim and assailant, suspected drug or alcohol-facilitated assault), the plan of

care is developed, and evidence collection proceeds. In this module, the examiner recognized the

importance of developing and integrating the proper communication skills necessary to formulate the plan