June 2019

The Bay Area-Silicon Valley

and India

Convergence and Alignment

in the Innovation Age

Since 1990, the Bay Area Council Economic Institute

has been the leading think tank focused on the

economic and policy issues facing the San Francisco

BayArea-Silicon Valley, one of the most dynamic regions

in the United States and the world’s leading center

for technology and innovation. A valued forum for

stakeholder engagement and a respected source of

information and fact-based analysis, the Institute is a

trusted partner and adviser to both business leaders

and government officials. Through its economic and

policy research and its many partnerships, the Institute

addresses major factors impacting the competitiveness,

economic development and quality of life of the region

About the bAy AreA CounCil eConomiC institute

and the state, including infrastructure, globalization,

science and technology, and health policy. It is guided

by a Board of Advisors drawn from influential leaders in

the corporate, academic, non-profit, and government

sectors. The Institute is housed at and supported by

the Bay Area Council, a public policy organization that

includes hundreds of the region’s largest employers

and is committed to keeping the BayArea the

world’s most competitive economy and best place

to live. The Institute also supports and manages the

Bay Area Science and Innovation Consortium (BASIC),

a partnership of Northern California’s leading scientific

research laboratories and thinkers.

Project Lead Sponsors

Project Supporting Sponsors

Contents

Executive Summary ...................................................4

Introduction ...............................................................7

Chapter 1

India’s Economy: Poised for Takeoff .........................9

Demographics and Disruption in the Labor Market .. 10

Tax & Currency: Out with the Old ........................... 13

A Rising Tide Lifts Some Boats ................................ 13

Turning a Corner ...................................................... 14

Chapter 2

Trade and Investment: Flow Management .............. 15

US-India Trade ......................................................... 17

A Regional Snapshot ................................................ 19

Trade Issues ............................................................. 21

Foreign Direct Investment:

Early Days, Strong Growth ....................................... 23

Chapter 3

The Bay Area Indian Community:

A Cross-Border Success Story .................................29

A New Wave of Immigrants ..................................... 30

The Community Today ............................................ 30

University Ties .......................................................... 33

Business Networks ................................................... 36

Chapter 4

Indian States: Laboratories of Innovation ...............39

City Competitiveness............................................... 42

Chapter 5

Innovation, Startups and Investment:

Poised for Breakthrough .........................................45

Venture Investment .................................................. 46

Bay Area Connections ............................................. 48

Chapter 6

Information Technology: Upward Mobility .............51

Government Initiatives ............................................. 54

Trends ...................................................................... 55

The Bay Area-IT Connection Shifts ......................... 55

Chapter 7

Healthcare/Life Sciences: Care in the Cloud ...........69

Pharmaceuticals ....................................................... 70

Trends ...................................................................... 71

Government Initiatives ............................................. 72

The Bay Area and India ............................................ 72

Slow Progress in Life Sciences Investment .............. 73

Chapter 8

Energy/Environment: Cleaner is Better ..................75

A Growing Need for Renewables ............................ 75

Where Energy and the Environment Intersect ........ 77

Pervasive Pollution ................................................... 79

Trash for Cash .......................................................... 80

Bay Area Laboratories and

Companies Address the Market .............................. 80

Chapter 9

Smart Cities: Order from Chaos ..............................85

India’s Plan ............................................................... 85

The Bay Area and India ............................................ 87

Chapter 10

Fintech: Data Puts Money to Work .........................89

The Bay Area and India ............................................ 92

Notes .......................................................................95

Acknowledgments

This report was developed and written by Sean Randolph,

Senior Director at the Bay Area Council Economic

Institute, and Niels Erich, a consultant to the Institute.

The Institute is deeply grateful to the co-chairs of

this project, Dr. Nandini Tandon of Tenacity, and

William Ruh, CEO of Lendlease Digital, who provided

extraordinary leadership and guidance to the project.

It also wishes to thank Priya Tandon, special advisor

for India to the Bay Area Council, who provided active

support and liaison in India.

This report would not have been possible without the

generous support of its sponsors Infosys, GE Digital,

J. Sagar Law, Tech Mahindra, Salesforce, Greenberg

Traurig LLP, and WestBridge Capital.

We also wish to thank the many people who

contributed to the research process with their time,

information, and insights:

Mukesh Aghi, President & CEO, US-India Strategic

Partnership Forum

Brett Allor, Senior Director, Market Strategy and

Research, SF Travel

Arogyaswami Paulraj, Professor Emeritus,

Stanford University

Harshul Asnani, Senior Vice President, Tech Mahindra

Ridhika Batra, Director USA, Federation of Indian

Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI)

Daljit K. Bains, Principal, dkb

Sumir Chadha, Co-founder & Managing Director,

WestBridge Capital

John Chambers, CEO, JC2 Ventures

Chris Cooper, COO, Sequoia Capital

Hubertus Funke, EVP & Chief Tourism Officer, SF Travel

SK Gupta, Managing Director and Co-Founder,

Ascend-Pinnacle

Sheryl Hingorani, Systems Analysis and Engineering,

Sandia National Laboratories

Anjali Jaiswal, Senior Director International Program–

India, National Resources Defense Council (NRDC)

Dr. Anula Jayasuriya, Founder & Managing Director,

EXXclaim Capital

Mohanjit Jolly, Partner, Iron Pillar Fund

Bakul Joshi, President, Multiple Access CA. Corporation

Sanjeev Joshipura, Executive Director, Indiaspora

Dr. Amit Kapoor, Chair, Institute for Competitiveness

Rajat Kathuria, Director & CE, Indian Council for

Research on International Economic Relations

Ajay Kela, President & CEO, Wadhwani Foundation

Aslesha Khandeparkar, Country Head and Senior

Director–India, Oracle

Shweta Kohli, Director, Public Policy & Government

Affairs–India and South Asia, Salesforce

Luke Kowalski, Corporate UI Architect, Oracle

Dr. Ashutosh Lal, Director–Thalassemia, UCSF Benioff

Children’s Hospitals–Oakland

Dr. Bertram Lubin, Executive Adviser for Children’s

Health, UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals–Oakland

Gautam Lunawat, Partner, McKinsey & Company

Rupinder Malik, Partner, J. Sagar Associates

Dr. Arun Majumdar, Co-Director, Precourt Institute for

Energy, Stanford University

Anita Manwani, Board of Directors, Ashoka University

Carolyn McNiven, Partner, Greenberg Traurig LLP

Prasant Mohapatra, Vice Chancellor for Research, UC Davis

Mahesh Narayanan, India Country Manager, LinkedIn

Robert Nelson, Partner, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP

Adithya M.R. Padala, President & CEO, UmeVoice

Krish Panu, Managing Director, PointGuard Ventures

Pablo Quintanilla, Director, Public Policy Asia-Pacific and

Latin America, Salesforce

Nisha Rajan, Senior Policy Coordinator, US-India

Strategic Partnership Forum

MR Rangaswami, Co-founder and Managing Director,

Sand Hill Group

Rekha Sethi, Director General, All India

Management Association

Dr. Kartikeya Singh, Deputy Director & Fellow,

Wadhwani Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies, Center

for Strategic & International Studies

Reshma Singh, Energy Technology, Lawrence Berkeley

National Laboratory

Jeremy Sturchio, Vice President and Head of

Government Relations Asia-Pacific, Visa

Andy Tsao, Managing Director, SVB Global Gateway

Thea Uppal, West Coast Manager, US-India

Business Council

Anurag Varma, Vice President, Infosys Ltd.

Vishal Wanchoo, CEO, GE South Asia

“

The San Francisco Bay Area is a vital

economic hub in U.S.- India trade and

continues to grow in both the diversity

of industries it encompasses and the

depth of opportunity it represents. India

cannot ignore the deep relevance this

area holds for it’s own economic growth

and we are pleased to see the Bay Area

Council step out with the India Report to

support continued partnership between

India and one of our nation’s most notable

economic powerhouses.

”

Nisha Biswal, President,

U.S.-India Business Council

and SVP, U.S. Chamber of Commerce

“

India will join China and the US in the top

tier of global economies, and that must

necessarily include building a top tier

Indian high technology industry. India

has to attract the right investments and

partnerships in this quest and I am sure

the US, and the Silicon Valley in particular,

will see this as a great opportunity.

”

Dr. Arogyaswami J. Paulraj,

Professor (Emeritus), Stanford University

“

The incorporation of these devices

will make India a leader in the space.

The opportunity for India and USA to

collaborate leveraging IOT is significant

in addressing many challenges. This is a

very exciting time for both democracies,

with huge potential, to partner, both for

innovation and implementation, leading

to positive impact in diverse sectors.

”

William Ruh, Co-Chair,

Bay Area-Silicon Valley India Focus,

Bay Area Council

and CEO, LendLease Digital

“

The Bay Area/Silicon Valley and India are

natural partners for innovation-based

economic growth. We are committed to

supporting and leveraging these ties for a

win-win for both the US and India.

”

Dr. Nandini Tandon, Co-Chair,

Bay Area-Silicon Valley India Focus,

Bay Area Council

and Co-Founder & CEO,

Tenacity Global Group Inc.

“

Economic growth is best served with the

inclusion of women in leadership and the

priority being given to it in the Bay Area-

India focus of the Bay Area Council is

very promising.

”

Priya Tandon, Special Advisor,

Bay Area Council

and Co-Founder & India CEO,

Tenacity Global Group Inc.

“

We are making great strides against

cancer but the road is a long one. And

now we have a new tool—Artificial

Intelligence that will help us move

faster. AI will be a great enabler in

transforming healthcare, specially

cancer. This transformation will be

further accelerated by USA and

India partnering and pooling their

complementary strengths, benefitting

their own citizens and collectively

impacting the global health at large.

”

Robert Ingram, Founding Chair,

CEO Roundtable on Cancer

2

MESSAGE FROM THE AMBASSADOR OF INDIA TO THE UNITED STATES

I extend my compliments to the India Focus of the Economic Institute of the

Bay Area Council (BACEI) for bringing out this timely report on building stronger

economic ties between the Silicon Valley and India titled, “Bay Area-Silicon Valley

and India: Convergence and Alignment in the Innovation Age”.

The recent outcome of the largest democratic vote on the planet – the General

Elections in India, with a clear and renewed mandate for the Government of Prime

Minister Narendra Modi provides a unique opportunity for further strengthening

the robust and comprehensive India-US strategic partnership. Prime Minister Modi

had said during his visit to Washington DC in June 2017, “We consider the USA as

our primary partner for India’s social and economic transformation in all our flagship

programs and schemes.”

The stewardship of Governor Gavin Newsom of the “Golden State” of California,

a leader in the United States in industries such as agriculture, pharmaceutical, finance,

information technology, aerospace, film and entertainment and tourism, can help

realize the untapped potential of bilateral cooperation. A decade ago, Governor

Newsom was the first-ever sitting Mayor of San Francisco to visit India. His focus on

building California’s external trade ties was evident in the fact that soon after taking

office earlier this year, he designated Lt. Governor of California Eleni Kounalakis as his

top representative to advance California’s economic interests abroad.

The potential for economic ties between the United States and India, the

world’s oldest and largest democracies is immense. India is today the world’s third

largest economy (PPP terms). It is poised to become a Five Trillion Dollar Economy

in the next five years and aspires to become a Ten Trillion Dollar Economy in the

next 8 years thereafter. The last five years also witnessed a wave of next generation

structural reforms, which have set the stage for decades of high growth. This includes

the path breaking Goods and Services Tax (GST) and other taxation reforms. The

country has leapfrogged to the 77th rank in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business

Rankings. With a young population and an expanding middle class, the Indian market

presents great opportunities for business.

3

It is therefore natural that bilateral trade and investments have shown a robust

growth. Bilateral trade reached $142 billion in 2018 growing by more than 13% from

$126 Billion in 2017. Trade deficit came down to $24.2 Billion, a decrease of 11.3%

in one year. India has been the top recipient of FDI in the world in the past few years

and has received over $239 Billion of FDI in the last five years. Over 400 of the top

Fortune 500 companies have their R&D facilities in India.

California is known world-wide for its innovative and important technology

firms such as Apple, Facebook, Oracle and Google. Many of these firms have

research centers in India and find a huge market and userbase there as well. India’s

skilled engineers power these Silicon Valley giants and also contribute to the Start-up

ecosystem of the Valley.

The Bay Area Council’s timely report on economic ties between Silicon

Valley and India traces the 100-year arc of their engagement propelled by Indian

immigrants on the US West Coast. It accurately captures India’s recent achievements

in the Ease of Doing Business, Competitiveness and Global Innovation indices and

rightly lays emphasis on India’s digital expansion in the fields of health, infrastructure,

agriculture, energy, payments, data analytics, IoT and e-commerce. Silicon Valley

technology companies have been among the first to realize the business potential

of India’s digital economy surging on the back of more than 500 million smartphone

users today and already higher per capita rates of data transmission than the US and

China. Among other things, the report chronicles the maturing of venture capital

funding between the Silicon Valley and India, spotlights new tie-ups in the digital

space for Indian IT-services companies, and presages growing partnerships in the AI,

blockchain, IoT and ‘moonshot’ spaces.

The report is a welcome and positive read on the India-US economic

relationship, in general. We laud the team at the Bay Area Council - President & CEO

Jim Wunderman, Co-chairs of BACEI’s India Focus Dr. Nandini Tandon and William

Ruh, Senior Director Sean Randolph and Special Advisor to BAC Priya Tandon - for

shining a light on the potential of India-Silicon Valley economic ties.

4

The Bay Area-Silicon Valley and India: Convergence and Alignment in the Innovation Age

Executive Summary

India’s economy has rapidly advanced and is now

the world’s sixth largest. GDP growth averaged 6.3%

from 1980–2016, and was 6.7% in 2017, with 7.3%

estimated for 2018 and 7.5% forecast for 2019. In

contrast to China, whose population is aging rapidly,

India is young: people aged 15–34 account for slightly

over a third of its population and most of its eligible

workforce. India’s economic structure is also changing,

as agriculture’s share has steadily declined to only

about 15% of output, and services now dominate (at

more than 50%). India’s middle class is growing, and

urbanization is accelerating.

This transformation is a work in progress. Agriculture still

employs almost 43% of the workforce. India’s vaunted

IT industry, though fast growing, employs relatively few

workers compared to traditional occupations, and while

official unemployment rates are low, many jobs are

temporary or part-time. India also continues to struggle

with a legacy of underperforming education, persistent

poverty, and government inefficiency. To address these

challenges and push India toward a position of global

leadership, the government of Prime Minister Narendra

Modi, which took office in 2014, has embarked on a

series of bold reforms to streamline government and

digitize the economy. That vision looks to a cashless

economy, digital government services, telemedicine

reaching into rural areas, more use of renewable energy,

and connectivity for rural as well as urban citizens

through 5G wireless networks.

For a country of India’s size, international trade is

relatively small, accounting for only 28.67% of GDP and

2.1% of world trade. Service exports are led by India’s

robust IT sector, which occupies a position of global

dominance. The United States is India’s largest global

customer for the IT, ITeS (IT-enabled services), and BPM

(business process management) sector, absorbing 62%

of global sales in each year since 2014. Due primarily to

its IT service exports, India enjoys a goods and services

trade surplus with the US, a source of conflict with the

Trump administration. On the investment front, the US

accounts for only 6% of India’s cumulative equity FDI

inflow, with US FDI to India having slowed in recent

years. Clearly, there is considerable room for growth in

two-way trade and investment. Silicon Valley is already

a major player, with $21 billion in cumulative investment

from 2003–2018, accounting for 79% of all investment

from California.

As this suggests, the Bay Area is a major economic

partner for India. This has a social and demographic

base, as California is home to 20% of Indian immigrants

to the US, with 506,971 residents of Indian descent. More

than 293,000 live in the Bay Area, primarily in Santa Clara

and Alameda counties. Compared to immigrants overall,

Indians tend to be professional and educated: nearly

three-quarters are employed in management, business,

science, and arts occupations; median income ($107,000

in 2015) is much higher than for the native-born or other

immigrant populations; and 77 percent hold a bachelor’s

degree or above. These numbers reflect the high

proportion of Indian immigrants who come to the US as

university students or as H-1B workers in jobs requiring

a university degree; 20,000 Indian students attend

California colleges and universities, with UC Berkeley the

largest host institution in Northern California. A vibrant

community of business and cultural organizations also

anchors India’s connection to the region.

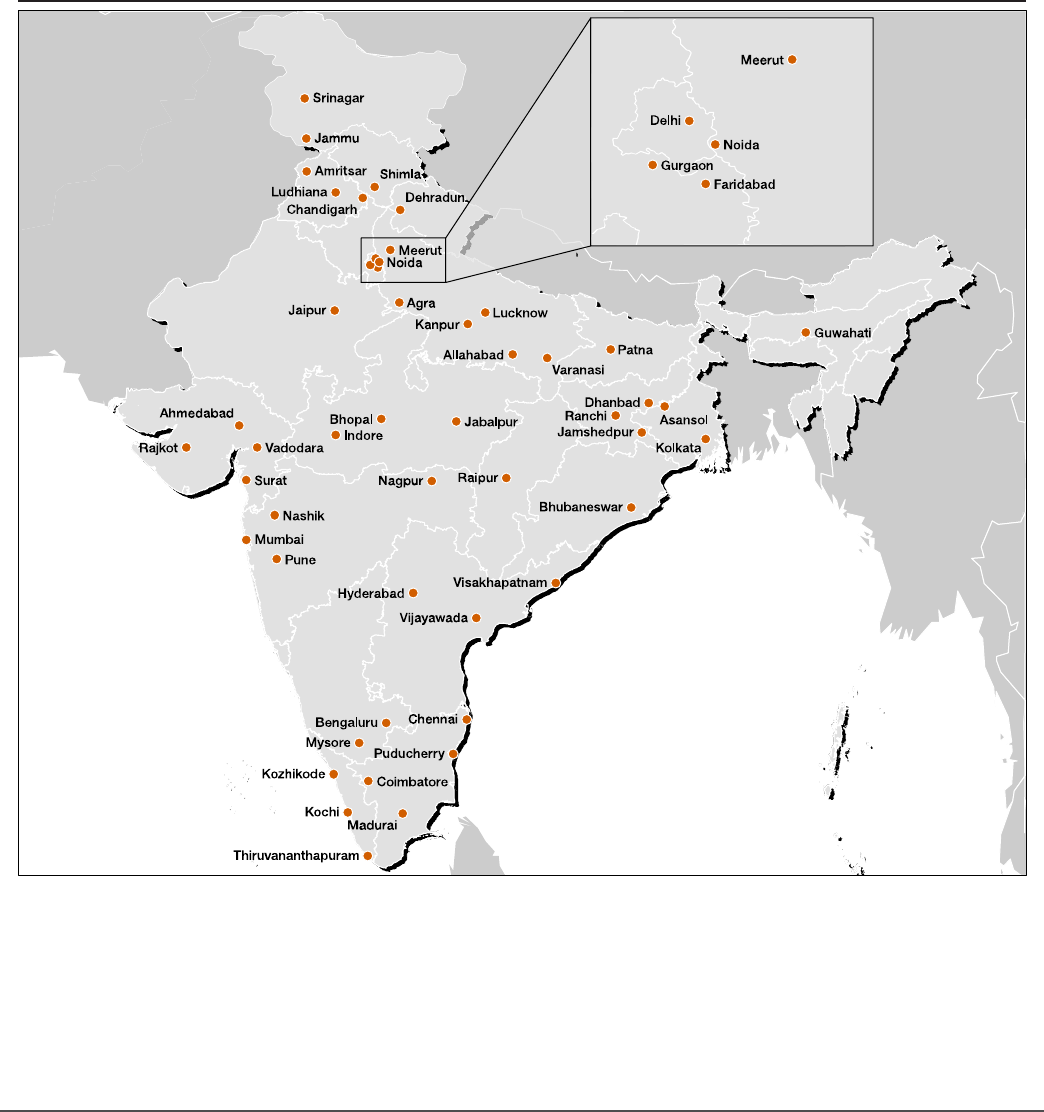

When considering opportunities in India, it is important

to understand that like the United States, India has a

large number (29) of highly diverse states that enjoy

considerable political autonomy and offer distinct

business environments. The largest states have the scale

of countries, with populations ranging from 60 million

(Gujarat) to almost 200 million (Uttar Pradesh). States can

serve as laboratories for innovation. Business strategies

therefore need to take into account not only national

government policies, but state environments as well.

Much still needs to be done before India can be

considered a world leader in innovation, but its status

is rising. A young, entrepreneurial population and a

5

Executive Summary

fast-growing domestic market make India a promising

site for venture investment. US venture firms, primarily

from Silicon Valley, are the biggest players. After a

flood of investment in the early 2000s, some firms left,

frustrated by slow returns on investment, but a growing

number of unicorns and recent high-profile exits are

changing the environment. As a result, both established

venture firms and newer market entrants are raising their

profiles through operations that give their Indian arms

more autonomy and decision-making authority. Most

innovation is taking place around goods and services

targeting India’s growing domestic market.

India is identified abroad with information technology

and with its leading IT services companies. IT,

IT-enabled services, and business process management

constitute a $167 billion sector that accounts for $126

billion in exports. As global IT demand is moving

beyond traditional network management, systems

integration, and software services toward new fields

such as mobile technology and digital services, Indian

firms are adjusting. Future export growth will come

primarily from digital services—cloud computing, big

data analytics, IoT, blockchain, automation, artificial

intelligence, and e-commerce. Silicon Valley plays a

part. Through their presence in the Valley, Indian IT firms

are investing, increasing R&D, and engaging startups

and other partners that will shape the future of the

industry. Some are developing service centers in the US

to recruit and train employees locally—in response to

customer needs, but also to increased pressure on the

H-1B visa system.

The Modi government’s Digital India initiative has

intensified the focus on digital capability within India.

Cloud services and e-commerce in particular are

poised for takeoff: the public cloud services market in

India is expected to grow by more than 35% to $1.3

billion in 2020; business to business (B2B) e-commerce

is expected to reach $700 billion; and business to

consumer (B2C) e-commerce is forecast to reach $102

billion. It is estimated that by 2023, India will have a

connected market of up to 700 million smartphones

and about 800 million internet users. Recognizing those

technology opportunities, Bay Area companies such as

Google, Facebook, Oracle, Cisco, Salesforce, VMware,

and Zendesk are increasing their investment.

Other sectors also show promise for partnerships. The

Modi government plans to double healthcare spending to

raise the quality of care, maintain affordability, and extend

preventive medical and wellness services to underserved

rural areas. Bay Area venture firms are investing in

specialty clinics, healthcare IT, diagnostics, pharmaceutical

manufacturing, and low-cost medical devices.

Energy and the environment are also priorities. Fossil

fuels power most of India’s 350 gigawatts of installed

electricity generation capacity; of that, 56–75% is coal-

fired generation. India has pledged under the 2015

Paris Climate Change Accord to cut greenhouse gas

emissions by 33–35% from 2005 levels by 2030 and

to achieve 40% cumulative electric power installed

capacity from non-fossil-fuel-based energy resources

over the same period. Those intentions build on the

government’s goal of increasing installed capacity of

renewables to 175 GW by 2022, more than doubling

the 75 GW capacity existing in early 2019. On the

environmental side, 15 of the world’s top 30 worst cities

for air pollution are in India, and 63% of sewage flowing

into rivers daily is untreated in urban areas.

Government agencies and states are looking to

California for solutions in renewable energy, energy

conservation and storage, and environmental mitigation.

Companies such as GE, whose digital activity is based

in the Bay Area, are developing technologies in India

focused on grid transmission and distribution software.

Bay Area venture firms are investing in decentralized

off-grid solar power, low-cost solar systems for homes

and small businesses, and solar-powered microgrids.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s International

Energy Studies (IES) Group has worked with India’s

government and businesses for more than two decades,

providing technical and policy analysis on power

generation, energy efficiency, and sustainable cities. It

also leads the US-India Joint Center for Building Energy

Research and Development (CBERD), in which a range

of Bay Area businesses, universities, and non-profit

organizations participate.

6

The Bay Area-Silicon Valley and India: Convergence and Alignment in the Innovation Age

Infrastructure, urbanization, and smart cities are related

fields where India’s needs and markets align with Bay

Area capabilities. India’s cities lag their global peers

in smart city technology. In response, the government

launched a Smart Cities Mission in 2015, targeting 100

cities for infrastructure and services upgrades, backed

by partial funding. Early projects focus on CCTV security

systems, smart streetlights, emergency warning and

response networks, free Wi-Fi along transit corridors

(which increased ridership), and “smart classroom”

upgrades to secondary and primary schools. Cities also

need better multi-agency planning and coordination,

data-driven decision making, and simplified processes

for permitting and land acquisition. Silicon Valley

companies are teaming with Indian IT and engineering

firms and startups to build out integrated command

and control centers that are critical to managing data

flows and coordinating functions, including integrated

data storage and security. Reflecting the range of needs

and opportunities, Cisco runs a Cisco Smart City center

in Bangalore (also known as Bengaluru) to showcase

how IoT technology and infrastructure can deliver

government services on demand via mobile devices;

enable smart streets and buildings, smart parking, and

smart meeting and work spaces; and connect users to

education, healthcare, and transportation.

India is also a large untapped market for financial

services. The Modi government sees mobile technology,

fintech, and a cashless society as keys to financial

empowerment and business growth, providing access for

ordinary Indians to credit, insurance, digital payments,

and e-commerce. Fintech acceptance and adoption have

grown rapidly, with the traditionally cash-driven Indian

economy responding well to the fintech opportunity

primarily triggered by the related surges in e-commerce

and smartphone penetration. The shift to digital

payments promises to revolutionize India’s economy,

and in the process, transform the financial sector. Credit

Suisse forecasts that digital payments will become a $1

trillion market in India by 2023. Bay Area companies like

Visa, PayPal, WhatsApp, and Google have made inroads

in financial services markets but face competition from

local service providers, as well as regulatory challenges.

As with any relationship between major countries, there

are complex issues. Imposition of 25% and 10% steel

and aluminum tariffs by the US in 2018 led India to

impose retaliatory tariffs in 2019. The US withdrawal of

Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) benefits has

also exacerbated the trade relationship. On the Indian

side, government proposals to require data generated in

India to be exclusively stored in India, and proposed data

privacy regulations that are among the most stringent

in the world, have drawn strong opposition from both

Indian and US IT and financial services companies.

India remains a complex place to do business, but with

reforms instituted by the Modi government, barriers

have fallen and many processes have been simplified.

The re-election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi to a

second term in May 2019 assures that these reforms

will continue. Sustained economic growth and national

strategies that push digitization across a range of

sectors and services are creating unique synergies with

the Bay Area that open the door to new opportunities,

as Bay Area companies expand their global footprint

and diversify their market presence in Asia.

7

Introduction

India and the United States are poised at the threshold

of a closer, more productive relationship than at any

point in the recent past. The two countries had been

distant during the years of the cold war, as the United

States confronted the Soviet Union and India embraced

a non-aligned status friendly to the Soviet Union

and economic policies at home that were socialist at

heart. Much changed with the end of the Cold War, as

successive Indian governments launched reforms to

open India’s economy, reduce bureaucratic burdens,

and strengthen market forces. A groundbreaking

nuclear agreement between the United States and

India, to enable cooperation on civil nuclear energy in

2005, reduced political strains and laid the foundation

for a new political dialogue.

1

More recently, initiatives

under India’s current Prime Minister Narendra Modi have

further reduced regulatory and bureaucratic burdens

on business and embraced digitization as a key to

modernizing India’s economy.

A shared strategic perspective on political and security

issues in the “Indo-Pacific region” has also brought

the two countries closer together. While India’s stance

remains independent and distinctly Indian, common

perceptions on regional security have deepened the

bilateral dialogue and cooperation. In September

2018, the United States and India held an inaugural

2+2 dialogue between India’s Ministers of External

Affairs and Defense and the US Secretaries of State

and Defense. Their joint statement declared that “The

Ministers reaffirmed the strategic importance of India’s

designation as a Major Defense Partner (MDP) of the

United States and committed to expand the scope of

India’s MDP status and take mutually agreed upon steps

to strengthen defense ties further and promote better

defense and security coordination and cooperation.”

2

The statement also affirmed that “the two countries are

strategic partners, major and independent stakeholders

in world affairs”

3

and opened the door to defense

industry supply chain linkages.

Along these lines, a new Communications Compatibility

and Security Agreement (COMCASA) now facilitates

interoperability between Indian and US defense forces,

providing India access to more advanced communications

technology for defense equipment purchased from the

United States and from US allies with similar equipment.

4

In July 2018, US Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross

announced that India would be granted Strategic Trade

Authorization (STA-1) status similar to NATO allies, Japan,

Australia, and South Korea, facilitating the export to India

of high-technology products.

5

Significantly for Silicon Valley, the September 2+2

meeting included an agreement that an Indian liaison

will be included in the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU),

the US Defense Department’s innovation office in Silicon

Valley which seeks to accelerate commercialization and

deployment of cutting-edge technology from smaller

US technology companies in the defense procurement

system. DIU will coordinate with Indian teams from

Innovations for Defence Excellence (iDEX), a unit

created in August 2018 by India’s Defence Innovation

Organization

6

to foster an innovation ecosystem for

technologies in the defense and aerospace sectors.

7

These agreements build on ongoing dialogues,

including the India-US Strategic Dialogue on Biosecurity,

to which Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory is

a contributor.

8

The US-India strategic relationship was

further cemented with the passage in December 2018

of the Asia Reassurance Act of 2018 (ARIA), Section 204

of which identifies the central role of India in promoting

peace and security in the Indo-Pacific region, and

calls for a strengthening of diplomatic, security, and

economic ties between the two countries.

9

This US shift toward India corresponds with India’s

changing perception of itself and its role in the world,

as it moves from a historical position of “strategic

autonomy” toward a position of global leadership

that embraces strategic partnerships. India’s status as

the world’s largest democracy and its commitment to

8

The Bay Area-Silicon Valley and India: Convergence and Alignment in the Innovation Age

market economy principles provides a strong foundation

of shared values, but sustained commitment on both

sides will be required for the relationship to achieve its

full potential.

This emerging economic and strategic alignment builds

on an economic base that is decidedly modest. For

two nations of such size, bilateral trade and investment

is small—particularly compared to US trade and

investment with China and with economic partners with

much smaller populations and GDPs.

India’s scale, young population, technical capability,

entrepreneurial energy, and large immigrant population

in the region link it powerfully to the Bay Area and Silicon

Valley. For many years, Bay Area technology and other

companies have used India’s deep base of offshore IT

services, opening R&D centers across India, and making

the region the largest single source of partners for Indian

IT companies globally. As the IT industry changes with

the advent of AI and cloud computing, that relationship

will shift. New areas for partnership are also emerging

as India’s economy is rapidly digitized. Opportunities

will particularly grow in fields such as health, fintech,

infrastructure, smart cities, semiconductor and cellphone

manufacturing, and renewable energy—all fields where

the Bay Area excels and India’s needs and capacities will

grow. These linkages present opportunities for the Bay

Area and its Indian partners that are unique and large

scale, but that also will require focus and patience to

realize. For the Bay Area/Silicon Valley, it is time to take

anew look at India.

“

The most strategic

relationship between any

two countries in the world

is between India and

the United States. India

is at an inflection point

of exponential growth,

and implementation is

the biggest challenge.

Toachieve it, partnership

with the US, including

Silicon Valley, is important.

”

John Chambers, CEO, JC2 Ventures,

former Executive Chairman and CEO, Cisco

9

1

India’s Economy: Poised for Takeoff

The demographics are favorable.

The entrepreneurial optimism and

energy are infectious. Can a fractious

political system finally get out of its

own way?

A well-worn cliché about India is that it has a very bright

economic future—and has had for decades. In truth,

India’s economy has grown dramatically from a very low

base, pulling a massive population behind it, and the

road to prosperity is long. For many, progress is erratic

and frustratingly slow, with persistent poverty, inefficient

government, and underperforming infrastructure. But

there is another reality, of an economy that has grown

to become the world’s sixth largest, with deep reservoirs

of human capital, leading global businesses, armies of

motivated entrepreneurs, and potentially vast markets

that invite development.

Since the 1991, economic and governance reforms

that signaled the beginning of the end of the so-called

“License Raj”—the post-colonial tangle of laws,

regulations, fees, and taxation that stifled business

formation and innovation for decades — India has been on

a growth trajectory most nations would envy. GDP growth

averaged 6.3% annually over the 1980–2016 period and

remained solidly in the 5–8% range coming out of the

global recession, according to the International Monetary

Fund. The economy grew by 6.7% in 2017, and the IMF

has estimated 7.3% growth for 2018 and forecasts further

growth of 7.5% for 2019. India is now the world’s fastest-

growing large economy, surpassing China (6.6% growth

estimated for 2018 and 6.2% forecast for 2019).

1

India’s GDP has grown from $266.5 billion in 1991

2

to

nearly $2.6 trillion in 2017, edging past France to make

India the world’s sixth largest economy in nominal GDP

terms.

3

Per capita income, adjusted for purchasing

power parity (PPP), has increased six-fold over the

1991–2017 period, from $1,140 to $6,980, according

to World Bank data.

4

However, incomes vary widely

across states. A 2017 comparison of per capita income

for the four states that contribute the most tax revenues

(Maharashtra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka) with

per capita income for the four states that receive the

largest distributions from collected taxes (Uttar Pradesh,

Bihar, Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh) showed that

average income for people in the four richer states was

three times greater than the average for the four poorer

states.

5

The nationwide average per capita income

at current prices during 2017–2018 is estimated at

about $1,600 (Rs 1,12,835), according to data from the

Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation

(MOSPI).

6

Former Reserve Bank of India governor

Raghuram Rajan has said that in order to end extreme

poverty, the national average will need to rise four-fold

and become more widely distributed; getting there

could take 20 years.

7

This points to another conundrum

when considering India’s economy: average incomes

remain low, but India is home to a large and growing

middle class that numbers several hundred million.

10

The Bay Area-Silicon Valley and India: Convergence and Alignment in the Innovation Age

Over the next decade, it is expected that India will meet

or exceed the 7% GDP growth rate needed to keep

pace with population growth. The World Economic

Forum has estimated that between 2018 and 2030,

India’s marginalized and lower classes will shrink in

numbers, with more than 140 million households

added to the lower-middle and upper-middle income

tiers.

8

The IMF forecasts that India will be the world’s

fourth largest economy by 2022,

9

and the Economist

Intelligence Unit estimates that by 2027, India’s

consuming classes will have more premium consumers

than Japan or Korea.

10

Demographics and Disruption

in the Labor Market

According to India’s official jobs data, which is

released sporadically and is considered inconsistent,

the national unemployment rate has been historically

low for a workforce of some 520 million in 2017,

hovering around 4% since 1991.

11

However, there are

indications that despite India’s economic expansion,

finding work is becoming increasingly harder, and a

leaked government estimate for the year ending in

March 2018 suggests that the unemployment rate

has risen to at least 6.1%, the highest in more than 40

years.

12

In addition, the official rate masks important

realities, most notably a labor force participation rate

of only 52% in 2015 (the most recent year for available

data) and an informal economy that employs nearly

90% of workers in unincorporated firms with fewer

than 10 employees and no job security or pension

benefits.

13

Small businesses provide the largest share

of employment after agriculture and make a significant

contribution to India’s GDP.

14

Over time, the workforce has become more urban.

Agriculture—for decades India’s largest economic

sector—now produces only about 15% of economic

output while industry has edged up to slightly above

30% and services now dominate at more than 50%.

15

These trends correspond with a gradual but steady

migration from the countryside to cities, which offer

more opportunities and significantly higher wages.

16

In sharp contrast to China’s population, which is rapidly

aging, India’s population is young. People aged 15–34

make up slightly over a third of India’s population and

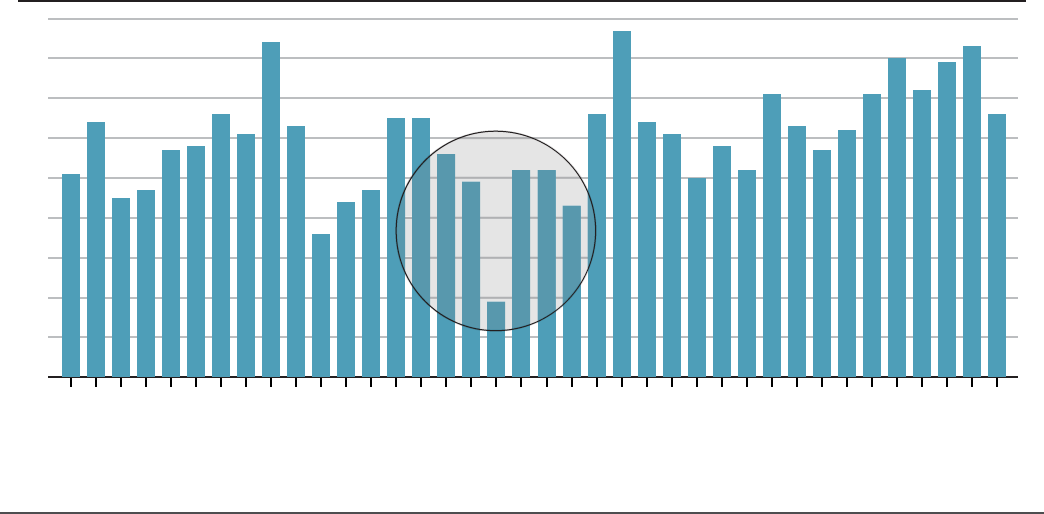

exhibit 1

India’s GDP growth rate averaged 6.3% annually over 1980–2016 and has

remained solidly in the 5–8% range coming out of the global recession.

India’s Annual GDP Growth Rate, 1980–2018, percent

0

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

20182016201420122010200820062004200220001998199619941992199019881986

1984

19821980

Source: IMF Data Mapper Graph: Bay Area Council Economic Institute

11

India’s Economy: Poised for Takeoff

most of its eligible workforce;

17

the median age is 28.

18

This is both an opportunity and a challenge: close to a

million young people reach working age every month,

which means India must create nearly 10 million new

jobs every year to keep up.

19

Contrasts in India continue across the spectrum.

Graduates of elite technical schools thrive as

entrepreneurs, building a soaring internet and gig

economy. Yet only a little over a quarter of the

population over the age of 25 has completed a

secondary education,

20

and the World Bank estimates

that well over a quarter of the youth population is

not in education, employment, or training (NEET).

21

A

fragmented labor market of small, informal businesses,

uneven educational opportunity, and job growth

concentrated in high-skill service sectors inhibits social

mobility and advancement for those less privileged.

While the country’s youth provide a potentially

deep well of human capital, India’s much vaunted

“demographic dividend” could become more a

demographic burden unless sufficient health, education,

and other benefits can be delivered to develop the

promise of this growing cadre of young people.

The urbanization narrative is also not as simple as

it sounds. Agriculture may produce only 15% of

economic output, but it was still employing 42.74% of

the nationwide workforce in 2017.

22

By contrast, the

information technology/business process management

sector for which India is most famous accounts for less

than 8% of GDP and hires only 3.9 million workers

23

(less than 1% of the workforce). While independent

work—ride share, e-commerce, online financial services,

and micro-entrepreneurship—have brought 18–22

million workers into the formal economy in recent years,

according to McKinsey,

24

most jobs are still part-time

and/or temporary, contributing to underemployment.

To address the skills gap, a National Skill Development

Corporation set up by the government has provided

training to more than half a million workers, but only 12%

of them have found better work as a result.

25

Tough labor

rules, most notably on hiring and firing by firms above

a certain size, have kept businesses intentionally small,

exhibit 2

Agriculture—for decades India’s largest economic sector—now produces

only about 15% of economic output, while industry has edged up to slightly

above 30% and services now dominate at more than 50%.

Contribution of Agriculture, Industry, and Services to India’s GDP, FY91–FY16, percent share of GDP

0

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Services

Industry

Agriculture & allied services

FY16FY14FY12FY10FY08FY06FY04FY02FY00FY98FY96FY94FY92

Source: Firstpost Graph: Bay Area Council Economic Institute

12

The Bay Area-Silicon Valley and India: Convergence and Alignment in the Innovation Age

preferring to avoid tax and regulatory costs and to grow

by automating or through temporary contract workers.

As a consequence, few Indian manufacturers achieve the

scale needed to compete nationwide or globally.

“As of now it seems India has a long way to go in

leveraging economies of scale,” acknowledges Nisha

Rajan, senior policy coordinator at the US-India Strategic

Partnership Forum (USISPF). “However, the trajectory

seems positive with the Modi government’s recent

efforts to initiate labor reforms in a bid to formalize the

Indian economy.”

Rajan points to consolidation of 44 central government

labor and employment laws into four unified codes:

industrial relations; social security and welfare; wages;

and occupational safety, health, and working conditions.

Specific reform proposals, in areas such as maternity

benefits, the right to unionize, hours of work and

overtime, contract labor, gig workers, and tips could affect

as many as 140 laws. “The present regime has displayed

the political will to reform in this area. There is no doubt

that without these reforms India is not likely to achieve the

targeted growth rates in its manufacturing sector.”

26

Distinct social pressures also affect the presence and role

of women in the workforce. In an April 2017 report, the

World Bank Group South Asia Region noted that India’s

female labor force participation (FLFP) dropped by an

estimated 19.16 million during the period from 2004–05

to 2011–12, from 42.7% to 31.2%. Not all of that

decline was necessarily negative. Approximately 53%

of the falloff occurred in rural areas, as the expansion

of secondary education and changing social norms

enabled young women aged 15–24 to continue their

education rather than join the labor force early. For the

overall category of women 15 years of age and above,

the most crucial factor explaining the drop in FLFP was

increased stability in family income due to the increase in

the relative contribution of regular wage earners and the

corresponding decline in casual laborers.

27

According to government data published in 2018,

women made up 46.23% of students enrolled in higher

education during 2015–16.

28

Furthermore, a government

data assessment by Press Trust of India found that for

the period from 2014 to 2017, the gender ratio of PhD

candidates at Indian universities was 5 women for every 7

men.

29

India’s 2014 National Sample Survey indicates that

exhibit 3

The India Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index lagged in 2017 after

demonetization and the goods and services tax launch.

India’ s Manufacturing Activity Trend: Purchasing Managers’ Index, monthly data, February 2016 to March 2019

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

Feb

2019

Dec

2018

Oct

2018

Aug

2018

Jun

2018

Apr

2018

Feb

2018

Dec

2017

Oct

2017

Aug

2017

Jun

2017

Apr

2017

Feb

2017

Dec

2016

Oct

2016

Aug

2016

Jun

2016

Apr

2016

Feb

2016

Source: IHS Markit; Trading Economics

13

India’s Economy: Poised for Takeoff

74.8% of urban women are literate, compared to only

56.8% of their rural counterparts. Yet women composed

only 14.8% of the urban workforce in 2015–16,

30

and the

Monster Salary Index report on the 2018 gender pay gap

in India found that women’s earnings were 19% less than

men’s.

31

The McKinsey Global Institute has estimated

that achieving gender parity by 2025—involving legal

protections, pay equity, physical security, child and elder

care, closing the education and skills gaps, and changing

diversity policies and attitudes—could add 68 million

more women to India’s workforce and $2.9 trillion more

in GDP to the economy than would be the case in a

business-as-usual scenario.

32

Tax & Currency: Out with the Old

Since coming to power in 2014, the government of

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has embarked on a series

of bold reforms designed to re-ignite growth, streamline

governmental processes, and propel India into the 21st

century’s digital economy. Two disruptive but ultimately

positive economic reforms introduced in the past two

years slowed business activity dramatically, but only on

a temporary basis. First, “demonetization” canceled and

replaced commonly used large-denomination notes—

86% of India’s currency—with new denominations, with

the goal of constraining criminal cash flows, tax evasion,

and counterfeiting.

33

While the move was generally

welcomed, it left ordinary consumers scrambling to

convert their cash, often standing in bank lines for

hours, while small businesses operating on a cash basis

were suddenly unable to pay workers and suppliers.

Consumer demand, new hires, and investment stalled

during the transition. The comparative ease with which

upper classes were able to convert their bills further

intensified the lingering, if not growing, sense of social

and economic inequality.

Second, a national goods and services tax (GST), effective

from July 2017, compounded the short-term friction and

uncertainty, even though many expect that its long-term

effects will be positive. The GST consolidated various

indirect central government and state taxes, including

sales, service, excise and state VAT taxes, customs duties,

surcharges, and state luxury and “sin” taxes. These

were absorbed into a combined central/state GST with

fewer tiers, to simplify filing, avoid double taxation, and

improve collections. Indirect tax collection is critical in a

largely informal economy of small incomes where only

1.5% of individual taxpayers—19 million people—paid

income tax in early 2017.

34

Nevertheless, the rollout of

the GST—which involved intensive debate over how

various goods and services would be classified, as well as

in many cases the need to set multiple tiers of taxation

relating to certain goods (as opposed to one unitary

rate)—was not as friction-free as proponents had hoped.

Combined disruption from demonetization and the

GST launch hit businesses hard in 2016–17, coming

on the heels of droughts in 2014–15 that hurt farmers,

rising oil prices that squeezed manufacturers, and poor

infrastructure that continued to cripple farm and retail

supply chains.

Amid confusion over tax liability and compliance, private

and state company investment hit a 13-year low in

the third quarter of 2017, according to estimates from

the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt. Ltd. in

Mumbai.

35

Since then, however, businesses have begun

to emerge from the shadows. Indian credit rating and

data research firm CRISIL reported surges of 19.7% in net

corporate tax collections and 18.6% in personal income

tax collections between April 2017 and February 2018.

36

While demonetization, GST, and other such reforms

will prove successful over time, the pace of recovery

and future development will be influenced by two

longstanding and growing constraints—wealth inequality

and a massive overhang of public and private debt.

A Rising Tide Lifts Some Boats

As mentioned earlier, the urban-rural divide, a

fragmented labor market of mostly small businesses,

and an education and skills gap have combined to

concentrate wealth in key cities and sectors.

A 2017 study by economists Lucas Chancel and Thomas

Piketty, using tax and survey data and national accounts,

shows a steady rise in the share of total national income

concentrated among the top 10% of Indian earners and

corresponding declines among the middle 40% and

bottom half of earners—trends underway since the late

1980s. While all incomes have grown since that time, the

author’s analysis of India’s income growth rates between

1980 and 2015 reveals a much higher income growth rate

for the top 10% of earners, who saw a 435% increase in

14

The Bay Area-Silicon Valley and India: Convergence and Alignment in the Innovation Age

their incomes compared to the bottom 50% of earners,

who experienced an income growth rate of 90%.

37

At the start of the January 2019 World Economic Forum

Annual Meeting, Oxfam‘s international executive

director noted that India’s top 10% of the population

held 77.4% of the total national wealth in 2018, with

the top 1% holding 51.53%.

38

India added 18 new

billionaires between 2017 and 2018, bringing the

total up from 101 to 119, an increase of 17.82%. By

comparison, China’s number of billionaires grew by

16.93 percent, rising from 319 in 2017 to 373 in 2018.

39

Rising wealth inequality, combined with lingering fallout

from demonetization and GST, have ramped up political

pressure on the Modi government. This was evident in

the administration’s 2018 budget: higher minimum price

supports for farmers; higher customs duties on imported

consumer goods to encourage inward investment;

national healthcare for poor families; and a corporate

tax cut targeted to small and mid-sized businesses.

40

Turning a Corner

Much work remains to be done to clear the obstacles

to faster growth, whether in privatizing mismanaged

state-owned businesses; enacting justice system reform

to unclog a national backlog of 30 million legal cases

(including 2 million pending for more than a decade);

41

easing extremely restrictive employment rules; reining

in energy and agriculture subsidies; or paring back

corruption in the allocation of land and capital for

infrastructure projects. Nevertheless, there is much

to applaud in what has already been accomplished

through initiatives—beyond demonetization and

GST—that include various forms of deregulation and

the aggressive promotion of digitization across the

economy. These include the secure digital delivery of

government benefits payments through the linking of

the Aadhaar digital identity system through mobile

phones to the Jan Dhan Accounts system—enabling

the opening of over 350 million “zero-balance” bank

accounts and allowing the rural and urban poor to

participate in the formal banking economy.

42

Ultimately, the government holds out the vision

of a cashless economy; universal healthcare with

telemedicine reaching into rural areas; a gradual

shift to cleaner energy over a distributed grid; and

modern, efficient water systems and food supply chains

connected in the cloud via 5G wireless networks and

sensors. A consensus is slowly forming in India that a

corner has been turned, that the country has indeed

come a long way since 1991, that momentum is

increasing, and that this time, despite the usual fits and

starts, may indeed be different.

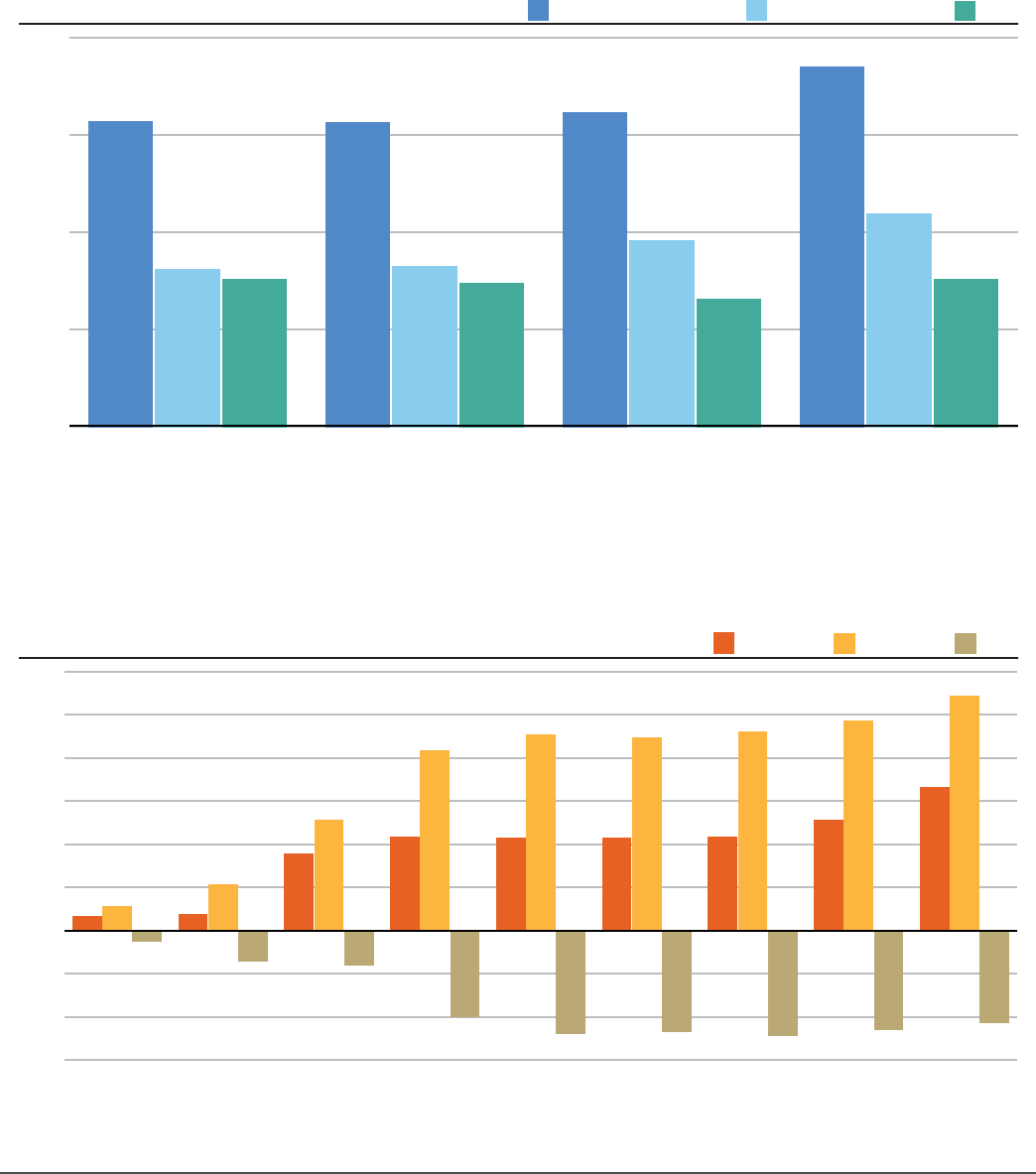

exhibit 4

Trends underway since the late 1980s show a steady rise in the share of total

national income concentrated among the top 10% of Indian earners and

corresponding declines among the middle 40% and the bottom 50% of earners.

Top 10%, Middle 40%, and Bottom 50% National Income Shares in India, 1951–2015

Middle 40%

Top 10%

Bottom 50%

25

30

35

40

45

50

55

1950

Percent of National Income

15

20

25

30

Percent of National Income

2010200019901980197019601950 201020001990198019701960

Source: Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty

15

2

Trade and Investment: Flow Management

India knows it needs to expand

trade and lure investment. But how

much, and what kinds? And can

the infrastructure meet pent-up

demand?

The dominant role of small, informal businesses that

compose most of India’s economy limits the country’s

trade and investment footprint. Firms have difficulty

scaling up to compete for global orders. For many,

staying outside the formal tax and regulatory system

precludes access to formal trade finance. Thin margins

and overreliance on part-time or temporary labor

remove the incentive to recruit more skilled workers

or train existing ones. Undercollection of taxes and

underpayment for utilities starve the government of

revenue to upgrade and maintain infrastructure. And

while many Indian companies have been growing in

size, outside of IT services the country still lacks the

nucleus of large, often export-oriented firms that the

September 2018 McKinsey “Outperformers” study has

identified with the most successful developing country

growth models over the last fifty years.

1

For an economy in the $2.6 trillion size range, India’s

2017 two-way goods trade total of $738.4 billion is

comparatively small, only 28.67% of GDP

2

and 2.1% of

world trade

3

(compared to the UK’s and France’s 41.53%

and 44.91% of GDP and 3.0% and 3.2% of world trade

respectively). More than two-thirds of India’s trade

activity concentrates in five states—Maharashtra, Gujarat,

Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Telangana, according to the

government’s 2017–18 Economic Survey.

4

Large firms

are not necessarily the largest exporters, as is the case

in other countries; the top 1% of Indian firms together

account for 38% of exports, versus 72% in Brazil, 68%

in Germany, 67% in Mexico and 55% in the US.

5

India’s

trade deficit is significant: the Ministry of Commerce

and Industry reported an annual deficit of $87.2 billion

for the fiscal year ending in March 2018, up from $47.7

billion in the year ending in March 2017.

6

Major goods imports include crude oil and mineral fuels;

gold and precious stones; electrical machinery; computers

and phone system devices, including smartphones;

organic chemicals; steel; and optical and medical

equipment.

7

Major exports are petroleum products; gems

and jewelry; vehicles; pharmaceuticals; and apparel.

8

Two-way services trade in 2017 totaled $294.7 billion,

with India running a net surplus of $75.9 billion.

9

Top

services import sectors include travel, transportation,

business services, and telecommunications, computer,

and information services.

10

Top services export sectors are

travel, transportation, software, and business services.

11

While India’s global services exports and imports

increased by 14.52% and 14.08% respectively between

2016 and 2017, the net surplus increased by 15.17%.

16

The Bay Area-Silicon Valley and India: Convergence and Alignment in the Innovation Age

exhibit 5

Two-way services trade in 2017 totaled $294.7 billion, with India running a

net surplus of $75.9 billion.

India Two-Way Services Trade, 2014–2017, US$ billions

0

$50

$100

$150

$200

Net

Services Imports

Services Exports

2017201620152014

$157.2

$81.1

$76.1

$156.3

$82.6

$73.6

$161.8

$95.9

$65.9

$185.3

$109.4

$75.9

Source: WITS, World Bank

exhibit 6

After reaching a plateau between 2013 and 2016, US imports and exports

both rose between 2017 and 2018; the net US deficit decreased slightly.

US Goods Trade with India, 1995, 2000, 2008, and 2013–2018, US$ billions

-$30

-$20

-$10

0

$10

$20

$30

$40

$50

$60

Net

Imports

Exports

201820172016201520142013200820001995

$3.3

$5.7

-$2.4

$3.7

$5.7

-$7.0

$17.7

$25.7

-$8.0

$21.8

$41.8

-$20.0

$21.5

$45.4

-$23.9

$21.5

$44.8

-$23.3

$21.6

$46.0

$25.7

$48.6

-$24.4

-$22.9

$33.1

$54.4

-$21.3

Source: Office of the United States Trade Representative Graph: Bay Area Council Economic Institute

17

Trade and Investment: Flow Management

Service exports are led by India’s robust information

technology (IT) sector, which in the last two decades

has established a position of global dominance. India’s

Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology

has estimated that exports in the IT-ITeS (IT-enabled

services) sector—which includes IT services, BPO

(business process outsourcing also known as business

process management or BPM), and Engineering R&D

and software development—will total $126 billion for

2017–18, up from $117 billion in 2016–17, reflecting

compound annual growth of more than 10% between

2013 and 2018. IT accounts for 57% of the IT-ITeS

sector, while BPO makes up 21.2%, and Engineering

R&D and software development composes 21.8%.

12

The US is the largest buyer of Indian IT-ITeS exports,

absorbing approximately 62% of global sales in each

year since 2014, according to the India Brand Equity

Foundation.

13

This suggests sales of more than $72

billion to the US in 2016–17.

According to UN Comtrade 2017 data, 58% of India’s

imports are from Asia, compared to 18% from Europe,

12% from the Americas, and 8.1% from Africa.

14

Half of

India’s exports go to Asia, compared to 19% to Europe,

21% to the Americas (including about 16% to the US),

and 8.2% to Africa.

15

China is the largest seller to India;

the US is India’s largest buyer.

16

US-India Trade

The US has run sustained trade deficits with India

that have widened over time, as goods trade volume

has increased and as the cross-border flow of IT-BPO

(IT services-business process outsourcing) exploded

during the 1990s. Two-way US-India goods trade in

2018 totaled $87.5 billion, with a net US deficit of $21.3

billion—both up significantly from a decade earlier, when

total trade was $43.4 billion with an $8 billion deficit.

17

Top US goods imports from India in 2018 included

precious metal and stone (diamonds), pharmaceuticals,

machinery, mineral fuels, and vehicles. Top exports to India

were precious metal and stone (diamonds), mineral fuels,

aircraft, machinery, and optical and medical instruments.

18

exhibit 7

The net US deficit in services trade with India has been shrinking by about

$1 billion per year since 2014, from $7.1 billion in 2013 and 2014 to $3.0

billion in 2018, a 57.7% decrease.

US Services Trade with India, 1995, 2000, 2008, and 2013–2018, US$ billions

-$10

-$5

0

$5

$10

$15

$20

$25

$30

Net

Imports

Exports

201820172016201520142013200820001995

$1.3

$0.9

$0.5

$2.8

$1.9

$0.9

$10.0

$12.7

-$2.6

$13.3

$20.4

-$7.1

$15.3

$22.4

-$7.1

$18.5

$24.7

-$6.1

$20.6

$25.8

$23.7

$28.1

-$5.2

-$4.4

$25.8

$28.8

-$3.0

Source: Office of the United States Trade Representative Graph: Bay Area Council Economic Institute

18

The Bay Area-Silicon Valley and India: Convergence and Alignment in the Innovation Age

exhibit 8

The Bay Area’s leading exports to India are fruit and nuts. India is a growing

auto manufacturing hub, and vehicles are now the leading imports.

Top Ten Exports to India Through the San Francisco Customs District, 2018 Compared to 2017, US$ millions

0 $100 $200 $300 $400

2018

2017

Mineral Fuel, Oil Etc.; Bituminous Substances; Mineral Wax

Products of Animal Origin, NESOI

Aluminum and Articles Thereof

Miscellaneous Chemical Products

Iron And Steel

Cotton, Including Yarn and Woven Fabric Thereof

Nuclear Reactors, Boilers, Machinery Etc.; Parts

Electric Machinery Etc.; Sound Equip.; TV Equip.; Pts.

Optical, Photo Etc., Medical or Surgical Instruments Etc.

Edible Fruit & Nuts; Citrus Fruit or Melon Peel

$588.8

$534.8

Top Ten Imports from India Through the San Francisco Customs District, 2018 Compared to 2017, US$ millions

0 $100 $200 $300 $400

2018

2017

Oil Seeds Etc.; Misc. Grains, Seeds, Fruits, Plants Etc.

Pearls, Precious/Semi-Precious Stones, Precious Metals; Coins

Leather Art; Saddlery Etc.; Handbags Etc.; Articles of Animal Gut

Fish, Crustaceans & Aquatic Invertebrates

Food Industry Residues & Waste; Prepared Animal Feed

Articles of Iron or Steel

Apparel Articles and Accessories, Knit or Crochet

Textile Art NESOI; Needlecraft Sets; Worn Textile Art

Furniture; Bedding Etc.; Lamps NESOI Etc.; Prefab. Buildings

Vehicles, Except Railway or Tramway, and Parts Etc.

Source: USA Trade Online, US Census Bureau Graph: Bay Area Council Economic Institute

19

Trade and Investment: Flow Management

US-India services trade in 2018 totaled $54.6 billion.

US services imports, valued at $28.8 billion, more than

doubled from 2008; services exports to India, valued

at $25.8 billion, were 2.58 times greater. The net US

deficit in services trade has been shrinking by about

$1 billion per year since 2014, from $7.1 billion in 2013

and 2014 to $3.0 billion in 2018, a 57.7% decrease.

Top services imports from India in 2018 were in the

computing and telecommunications services, IT, research

and development, and travel sectors. Top services

exports were in the travel, intellectual property (computer

software, audio and visual related) and transport sectors.

19

Exports to India supported an estimated 260,000 US

jobs in 2015, the latest year for which data is available,

according to a 2017 study by the East-West Center and

the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and

Industry (FICCI). More than 52,000 of those jobs were

in California.

20

A Regional Snapshot

Goods

A pattern of steady across-the-board growth applies to

Bay Area trade with India, where two-way India ocean

and air freight through the San Francisco Customs District

in 2017 totaled more than $1.7 billion.

21

Unlike the US

as a whole, the region has enjoyed a net trade surplus

with India since 2015—$1 billion in exports versus $700

million in imports. From 2013 to 2017, Bay Area exports

to India grew by nearly 52%; imports grew by 11%.

(NOTE: US Census Bureau trade data reported here

reflects not only exports produced and shipped or

imports received locally, but also includes other US

trade using the Bay Area as a gateway, as well as a small

share of transshipped goods with origins or ultimate

destinations abroad, such as Canada or Mexico.)

Nearly all of the $237 million in Bay Area air cargo bound

for India in 2017 moved through San Francisco and San

Jose International Airports; nearly all of the $802 million

in ocean freight moved through the Port of Oakland,

which also includes Oakland International Airport.

The potential for expanding US and Bay Area trade with

India trade is significant. As a 2017 Brookings analysis

highlights, Korea’s trade with the US is twice the size

of India’s, although Korea’s economy is 40% smaller;

China’s population is similar to India’s, yet its trade with

the US is six times larger.

22

Services

There is also opportunity to grow services trade

with India, and in particular US services exports. The

opportunity lies partly in opening the Indian market

to foreign legal, accounting, banking, insurance and

retail competition (see Trade Issues below), and partly

in nascent fields such as healthcare, clean energy,

infrastructure, smart cities, and logistics, which are

discussed in detail elsewhere in this report. These

opportunities particularly connect to the Bay Area,

givenIndia’s needs and what the Bay Area offers.

Currently, much of the Bay Area’s services trade with

India is in travel and tourism—Indian business travel,

tourism, and family visits in both directions—and in

technology-based business services provided by Indian

visa contract workers employed in the region. The

two are, in many respects, closely intertwined, but the

IT-BPO activity has a far larger impact on the regional

economy in terms of jobs and wealth creation and is still

the driver of most visitor traffic to and from India.

Visitors

Some 352,000 travelers visited California from India in

2018 and spent an estimated $788 million in the state,

according to Visit California, a non-profit marketing

organization that partners with the state’s travel industry.

Those numbers are expected to grow by almost 6%

annually to 443,000 visitors and estimated spending of

$992 million in 2021.

23

Demonetization hurt the Indian travel sector in 2016–17

by taking out of circulation large amounts of cash

typically kept on hand for travel and other discretionary

purchases. Then, between March and July of 2017, a

US-imposed ban on carry-on laptops and tablets on

arriving flights from eight Middle Eastern countries led

to a sharp drop-off in India-to-US travelers on popular

routes via the Emirates airline hub in Dubai and via

the Etihad Airways hub in Abu Dhabi. Etihad, which in

February had already begun scaling back its flights to

the US, completely eliminated its Abu Dhabi to San

Francisco flights in October.

24

20

The Bay Area-Silicon Valley and India: Convergence and Alignment in the Innovation Age

exhibit 9

Some 352,000 travelers visited California from India in 2018 and spent an

estimated $788 million in the state. Those numbers are expected to grow

by almost 6% annually to 443,000 visitors and estimated spending of

$992 million in 2021.

Number of Indian Visitors to California, 2009–2018

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

400,000

2018201720162015201420132012201120102009

153,000

182,000

184,000

190,000

240,000

262,000

291,000

319,000

333,000

352,000

Source: Visit California

However, overall demand for flights from India to the

West Coast soon recovered, and the short-lived laptop

ban seemingly created a window of opportunity for

Air India, which saw its bookings for flights to the US

double in the two weeks after the ban was announced.

25

After having launched direct flights from Delhi to

San Francisco in December 2015, starting with three

weekly flights and then doubling to six flights a week

in November 2016, Air India increased its service again

to nine flights a week in March 2018. United Airlines

also began providing non-stop flights between Delhi

and San Francisco with the launch of its “seasonal daily

service” in December 2019.

26

Global travel is on the rise in India, as the economy

grows, living standards improve, and vacations become

more accessible and frequent. In the premium segment

of the market, Indians are regularly exposed to print

and television images of California, and are intrigued by

its scenery, available travel experiences, and celebrity

culture. Until recently, the ease of obtaining visas has

been a plus for attracting Indian visitors. According to

the San Francisco Travel Association, India was one of

the four fastest growing international visitor markets

in 2018.

27

Visit California reports that 53% of visitors

from India are leisure travelers, combined business and

leisure travel is becoming more common, and Indian

visitors traveling as nuclear families is a new trend. The

long flight encourages a longer stay, an average of 19.6

nights, and the average spend is $2,527 per trip.

28

IT-BPO

Indian engineers and programmers contribute valuable

expertise to a Bay Area tech community that has, over

many years, struggled to find both the right global post-

graduate talent critical to innovation and the sizeable

numbers of skilled workers large firms need. Outsourced

skilled tech employment represents an important Indian

services export to the US and the Bay Area.

21

Trade and Investment: Flow Management

US Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) latest

available fiscal year data shows 67,815 Indian nationals

receiving initial H-1B visas in 2017, down from 70,737

in 2016. However, the number receiving extensions

for continuing employment totaled 208,608 in 2017,

up from 185,489 a year earlier. Initial visas are granted

for three years, with an option for a single three-year

extension. In total, Indian nationals received 75.6% of

H-1B visas approved in the United States in the 2017

fiscal year. Overall, USCIS approved 90.6% of the H-1B

visa petitions received in fiscal year 2017.

29

According

to reporting by The Mercury News, that approval rate

dropped to 85% for 2018, while the rate of delays rose

sharply, and it appears that greater scrutiny and increased