WHAT WE HAVE LEARNED

FROM

THE

AIDS EVALUATION OF

STREET OUTREACH PROJECTS

A SUMMARY DOCUMENT

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Atlanta, Georgia 30333

CDC

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL

AND PREVENTION

Copies of this publication can be obtained by

writing Office of Communications, NCHSTP

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

1600 Clifton Road, N.E., Mailstop E-06

Atlanta, GA 30333

faxing 404–639–8628

or calling NCHSTP Voice Information System

1–888–232–3228

Press 2, 5, 1, and 1 as prompted

and request

What We Have Learned from AESOP.

W

HAT

W

E

H

AVE

L

EARNED

FROM

THE

AIDS E

VALUATION

OF

S

TREET

O

UTREACH

P

ROJECTS

A S

UMMARY

D

OCUMENT

Edited by

Judith B. Greenberg, PhD

Division of STD Prevention

and

Mary S. Neumann, PhD

Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention

National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Atlanta, Georgia

1998

S

ITE

C

OLLABORATORS

Agency Principal Investigator

ADAPT, New York Daniel Fernando, PhD

Children’s Hospital Michele Kipke, PhD

of Los Angeles

County of Los Angeles John Schunhoff, PhD

Department of Anna Long, PhD,

Health Services Project Director

Georgia Department Claire Sterk, PhD

of Human Resources

Philadelphia Health Rose Cheney, PhD

Management Corporation

San Francisco Department Alice Gleghorn, PhD

of Public Health

University of Illinois, Chicago Wayne Wiebel, PhD

School of Public Health Bob Nettey, MD,

Project Director

Victim Services Agency, Helene Lauffer

New York Michael Clatts, PhD,

Co-Investigator

CDC Collaborators

John E. Anderson, PhD, Coordinator

Judith Greenberg, PhD, Project Officer

Robin MacGowan, MPH, Project Officer

Jo Valentine, MSW, Project Officer

Other CDC Contributors

Linda Kay, MPH

May Kennedy, PhD

Mary Spink Neumann, PhD

Lloyd Potter, PhD

John Santelli, MD

Kathy Stark, BS

Linda Wright-DeAgüero, PhD

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

The editors thank Marie Morgan, from the Division of HIV/AIDS

Prevention, for her hours of collaboration with stylistics, layout,

and proofing of the many iterations of this manuscript. We also

thank Lynda Doll, PhD, and T. Stephen Jones, MD, from the Divi-

sion of HIV/AIDS Prevention–Intervention Research and Support,

for their detailed comments on earlier versions.

C

ONTENTS

Introduction

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1

Annotated Bibliography

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9

Articles

A Probability Sampling for Assessing the

Effectiveness of Outreach for Street Youth

- - - - - - - - -17

Michele D. Kipke, Susan O’Connor, Burke Nelson,

and John E. Anderson

A Storytelling Model Using Pictures for HIV

Prevention with Injection Drug Users

- - - - - - - - - - - -29

Anna Long, Judith Greenberg, Gladys Bonilla,

and Ronald Weathers

Elements of an Intensive Outreach Program for

Homeless and Runaway Street Youth in

San Francisco

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -47

Alice A. Gleghorn, Kristen D. Clements, and

Marc Sabin

Association between Self-Identified Peer-Group

Affiliation and HIV Risk Behaviors among

Street Youth

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -61

Michele D. Kipke, Jennifer Unger, Raymond Palmer,

Ellen Iverson, and Susan O’Connor

Enhanced Street Outreach and Condom Use

by High-Risk Populations in Five Cities

- - - - - - - - - - -83

John E. Anderson, Judith Greenberg, and

Robin MacGowan

Products and Contacts for

Intervention Replication

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 111

1

I

NTRODUCTION

The AIDS Evaluation of Street Outreach Projects (AESOP) was a 5-

year study designed by the Centers for Disease Control and Pre-

vention (CDC) in collaboration with researchers representing

agencies at eight sites. This cooperative study, which included

community-based organizations and health departments, was

conducted from October 1991 through September 1996. Its pur-

pose was to support studies to describe outreach services to injec-

tion drug users (IDUs) and youth in high-risk situations, calculate

the costs of such services, and develop and evaluate enhanced on-

the-street services for these populations. Collaborators at five of

the eight sites (Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, and Phil-

adelphia) focused on outreach to IDUs. At three sites (Los Ange-

les, New York, and San Francisco), the focus was youth.

M

ETHODS

The research was conducted in several phases. During the

forma-

tive phase

of approximately 1 year, the sites conducted the com-

munity assessment process (CAP) to gain maximum information

about the targeted community, including how services were deliv-

ered to these populations, and to develop specific enhancements

to outreach that could be delivered on the street to the same pop-

ulations. To assist the staff at the sites, CDC collaborated with

LTG Associates, Inc., a private contractor, to adapt the community

identification (CID) method. This method included interviews with

groups of persons who interacted with the target population as

well as interviews with members of the population themselves. A

detailed description of CID can be found in Tashima, 1966. Using

the formative research, sites developed interventions plus a design

for evaluating them.

After the formative phase, AESOP entered the

evaluation phase

.

A quasi-experimental design (a study and a comparison area) was

used for each of the eight communities. Each area was to have

adequate numbers of the target group and some ongoing level of

street outreach. Cross-sectional, closed-ended surveys of the target

populations in the control and comparison areas were conducted

AESOP

2

before and after the development and implementation of interven-

tion enhancements. These surveys measured risk behavior, expo-

sure to outreach, and readiness for behavioral change. Staff at

each site conducted at least two preenhancement rounds of inter-

views at intervals of approximately 3 months between January

and August of 1993 and two postenhancement rounds between

1994 and 1995, once the enhancements had been fully imple-

mented for at least 3 months.

Sampling of IDUs and youth was conducted so that it would be as

representative as possible; interviews were conducted at locations

frequented by these populations. Researchers in each city identi-

fied and defined primary sampling units (PSUs) within the study

and comparison areas. The PSUs could be of two types: fixed sites

(shelters, meal programs, drop-in centers) and on-the-street sites

(congregating areas; drug-buying, or "copping," areas; shooting

galleries). The PSUs were observed at multiple times of the day to

determine the relative number of potential respondents at each

site. The number of interviews to be obtained from each PSU was

set to be proportional to this measure of size. If the sample con-

tained fixed sites (e.g., drop-in centers, shelters) and on-the-street

locations, a predetermined percentage of interviews were set for

fixed and on-the-street domains. Interviewing within PSUs was

systematically scheduled by time of day and day of week so that

all relevant times would be represented. Within PSUs, respon-

dents were selected by using systematic methods, such as select-

ing every n

th

potential respondent by predetermined counting.

Once persons were selected, a screening questionnaire was

administered to determine eligibility, and the complete question-

naire was administered to those who were eligible.

E

NHANCEMENTS

AESOP enhancements differed by site because of the diversity of

participating outreach programs, geographic diversity, and the

inclusion of youth and IDUs. Enhancements were focused on the

outreach workers and encompassed a wide range of strategies:

increased training (e.g., training in stages of change, training in

the finger-stick method for HIV testing); additional resources such

I

NTRODUCTION

3

as a storytelling model with pictures for engaging the clients in

risk assessment (see article by Long et al. in this monograph),

referral tracking cards and incentive packages; a mobile van;

improved direct supervision; improvements in recordkeeping of

the delivery of outreach services and referrals; coordination of out-

reach services with other agencies at a particular site; expanded

services, including the addition of specialized staff such as a refer-

ral specialist; a storefront location for more comprehensive ser-

vices to youth (see article by Gleghorn et al. in this monograph);

changes in selection criteria for hiring outreach workers or super-

visors; and social and emotional support to minimize burnout.

Three to seven enhancement strategies were developed at each

site. Quality assurance procedures were developed for on-the-

street monitoring of outreach workers to ensure that enhance-

ments were being delivered as intended.

Eligible IDUs were defined as persons within the geographical

boundaries of the study areas who had injected illegal drugs in the

past 3 years. At three sites with lower numbers of IDUs —Atlanta,

Los Angeles, and Philadelphia—up to 30% of the sample were

allowed to be persons who had used crack cocaine within the past

month. Eligibility for youth was based on age (12 to 23 years) and

lack of permanent residence (recurrently without shelter during

the past year or without permanent shelter during the past 2

months) or use of the street economy for support (drugs, prostitu-

tion, panhandling, crime).

B

EHAVIORAL

E

PIDEMIOLOGY

K

EY

F

INDINGS

1. The initial rounds of survey research indicated that the AESOP

populations engaged in much higher levels of sexual risk

behavior than the levels found in general population surveys.

2. After AESOP enhancements, the percentages of those who had

used condoms during their most recent intercourse ranged

from 57.9% to 71.8% for casual partners. Those percentages

approach the year 2000 health objectives: 50% for unmarried

sexually active persons, 60% for sexually active women aged

AESOP

4

15 to 19 years, 75% for sexually active men aged 15 to 19

years, and 60% for IDUs. Rates for steady, or main, partners

remained low.

3. Among the high-risk populations studied, the highest rate of

condom use was observed for anal sex, followed by vaginal and

oral sex.

4. Outreach workers from a variety of agencies reached a size-

able percentage of IDUs in their communities and supported

them in seeking medical care, especially in seeking counseling

and testing for HIV and treatment for drug use. One third to

two thirds of respondents who had seen an outreach worker

from any program in the preceding 6 months reported having

received referrals for these two services. One third to one half

of respondents reported that they then sought these services.

5. In addition to sexual practices, street youth are at risk

through high rates of drug use that includes sharing of

syringes.

6. Youth in contact with street outreach are much more likely to

have sought health care, HIV counseling and testing, or treat-

ment for a sexually transmitted disease (STD) or for substance

use than are youth who are not in contact with street out-

reach.

7. Among street youth, a history of STD is significantly associated

with current substance use and having multiple sex partners.

8. Homelessness and crack use are associated with lower levels

of stage of change for not sharing needles.

9. IDUs are more likely to report safer drug behavior than safer

sex behavior and tend to be at a higher level of stage of change

for not sharing needles than for condom use.

I

MPLICATIONS

FOR

R

ESEARCHERS

1. Cross-sectional data on street populations do not reveal the

time frame or process by which persons become acculturated

to and integrated into the street economy, which includes

trading of sex and drugs. The degree to which clients are

I

NTRODUCTION

5

acculturated and the length of time they have been on the

street may influence their willingness or ability to change their

behaviors.

2. Research should be planned separately for street populations

of youth and IDUs (e.g., separate goals for interventions, sepa-

rate questionnaires, and separate intervention enhancements).

3. Many factors can affect the delivery of services to street popu-

lations – weather, police activity, riots, changes in laws, urban

relocation because of special events, even the death of a cul-

tural icon, such as Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead band.

After Garcia’s death, large numbers of youthful

Deadheads

disappeared from the San Francisco street scene. These fac-

tors should be recorded as they happen, and they should be

considered in data analysis.

4. Surveys of target populations frequently measure only the

elimination of risk behaviors (e.g., ceasing substance use) and

often do not consider reductions in risks (e.g., not injecting in

shooting galleries) or preparations to change (e.g., intention to

buy bleach). Including such gradations of change in surveys

can provide more sensitivity in measuring behavior change at

the community level.

5. The effects of dosage or number of exposures to outreach and

of rates at which innovations diffuse in communities are impor-

tant variables to measure in community-level interventions.

6. Measures of reduced risk can become outmoded during a

study (e.g., guidelines for bleaching needles changed during

AESOP), and research methods should be flexible enough to

allow for this.

7. In studying homeless populations, investigators should in-

clude length of time homeless as a variable.

I

MPLICATIONS

FOR

S

ERVICE

A

GENCIES

1. High percentages of street populations reported contact with

outreach workers, although many reported continued high-

risk behaviors. For many persons, street outreach may not be

sufficient for behavioral change.

AESOP

6

2. Among street youth, substance use and having multiple sex

partners are significantly associated with a history of STD;

therefore, in a clinical setting, an STD diagnosis for a person

from this population may be a marker for other high-risk sex

and drug-using behaviors.

O

UTCOME

E

VALUATION

K

EY

F

INDINGS

1. Theory-based street outreach approaches can be used by

trained indigenous outreach workers.

2. Evaluation of street outreach programs is inherently difficult

and requires multiple approaches.

3. There are several types of street outreach, ranging from brief

contacts to more in-depth encounters between workers and

clients.

4. Street outreach can be an effective mechanism for referring

high-risk persons to treatment.

5. Street outreach distribution programs can affect condom use

by high-risk populations.

a. Having a condom at the time of interview was the strongest

and most consistent predictor of condom use at most recent

intercourse.

b. Obtaining condoms from outreach workers was indirectly

associated with condom use because this factor was

strongly related to carrying a condom.

c. Higher level of stage of change (consideration or intention)

for condom use by persons who do not use condoms is

linked to outreach exposure.

6. Costs of street outreach can be measured: at the AESOP sites,

the costs, relative to the medical costs of AIDS cases, were low.

If 2 of 10,000 contacts reduced their high-risk behavior so as

to avoid HIV transmission, outreach would yield a net benefit.

I

NTRODUCTION

7

7. Among the AESOP sites, the average cost of outreach contact

for high-risk youth was nearly twice that for IDUs. Much of

the increased cost was for facilities (e.g., drop-in centers) and

materials (e.g., food, travel vouchers, hygiene kits).

8. Outreach workers from a variety of agencies reach a sizeable

percentage of IDUs in their communities and support them in

seeking medical services, especially in seeking HIV counseling

and testing and drug treatment.

I

MPLICATIONS

FOR

S

ERVICE

A

GENCIES

1. Street outreach can be expanded to include a variety of ser-

vices, including HIV counseling and testing on the street, the

use of varied theory-based interventions (e.g., staging clients

for risk-reduction messages), even advocacy.

2. Since the interpersonal dynamics of steady and casual sexual

partnerships are different, condom promotion messages

should be tailored to the type of sexual relationship the client

has.

3. After-care referrals, such as support groups and drug coun-

seling services, need to be emphasized to accommodate the

high numbers of IDUs exiting drug treatment.

F

UTURE

R

ESEARCH

Q

UESTIONS

1. Is street outreach more effective with certain types of drug

users (e.g., on the basis of consumption method or drug of

choice)?

2. What types of sex take place at different venues (e.g., vaginal

sex at crack houses, oral sex at adult bookstores, anal sex at

parks)?

3. Which is the antecedent: drug use or prostitution? Does the

antecedent differ by ethnicity, age, or sex?

AESOP

8

Reference

Tashima, N., Crain, C., O’Reilly, K.R., & Sterk-Elifson, C. (1966).

The community identification (CID) process: A discovery

model.

Qualitative Health Research,

6, 23-48.

9

A

NNOTATED

B

IBLIOGRAPHY

B

EHAVIORAL

E

PIDEMIOLOGY

(F

INDINGS

FROM

B

ASELINE

I

NTERVIEW

D

ATA

)

Anderson, J.E., Cheney, R., Clatts, M., Faruque, S., Kipke, M., Long,

A., Mills, S., Toomey, K., & Wiebel, W. (1996). HIV risk

behavior, street outreach and condom use in eight high-risk

populations. AIDS Education and Prevention, 8(3), 191-204.

The populations surveyed engaged in high levels of sexual risk

behavior: 20% to 46% reported two or more sex partners in the

past month. Most of the injection drug users and high-risk

youth were at risk through unprotected sex with main part-

ners; 56% to 75% reported protected vaginal sex with casual

partners. Of this group, 58% to 84% had been tested for HIV

infection, compared with 25% of the national adult population.

Having a condom at time of interview was the most consistent

predictor of condom use during most recent intercourse. A

variable percentage of injection drug users had shared needles

in the past month (10% to 53%). Many respondents had been

in contact with street outreach programs and had received

condoms, bleach, and other materials from workers.

Anderson, J.E., Cheney, R., Faruque, S., Long, A., Toomey, K., &

Wiebel, W. (1996). Stages of change for HIV risk behavior:

Injecting drug users in five cities. Drugs and Society, 9(1/2), 1-17.

Respondents from the street-based samples interviewed at the

five AESOP sites that were focused on injection drug users had

a very high level of risk for HIV, in terms of sex and drug-using

risk behavior. The level of stage of change for condom use was

higher for casual partners than for main partners. Having a

condom at interview was the most consistent predictor of

respondent’s level of stage of change for condom use. Home-

lessness and crack use were associated with lower level of stage

of change for not sharing needles. Program staff need to be

aware of the predominant level of readiness to change in order

to design and implement effective programs.

AESOP

10

CDC. (1993). Assessment of street outreach for HIV prevention—

Selected sites, 1991-1993. MMWR, 42 (45), 873, 879-880.

This report is a description of the first 2 years of the AESOP

project and includes results from the initial round of closed-

end interviews. Results indicated that 17% to 65% of injection

drug users and 23% to 46% of youth in high-risk situations

(YHRS) reported talking with an outreach worker; 14% to 58%

of IDUs and 11% to 26% of YHRS had received HIV prevention

literature; 16% to 58% of IDUs and 22% to 39% of YHRS had

received free condoms; and 13% to 55% of IDUs and 7% to

10% of YHRS had received bleach kits from outreach workers.

These findings suggest that IDUs and YHRS can be identified

and reached through outreach programs; will talk with

outreach workers about HIV prevention; and will accept HIV

prevention literature, materials, and referral services from

outreach workers.

Clatts, M.C., Bresnahan, M., Davis, W.R., Springer, E., & Backes, G.

(1997). The harm reduction model: An alternative approach to

AIDS outreach and prevention for street youth in New York City.

In P. Ericson et al. (Eds.), Harm reduction: A new direction for

drug policies and programs. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

The authors provide a demographic and behavioral profile of

street youth in New York City and discuss the history of AIDS

prevention services for these young people. A network of

outreach programs developed for AESOP, the Youth At Risk

Cooperative, and the foundation for the network’s training

program for outreach workers in the harm reduction model

are described. Case study material from staff who integrated

the model into case management activities provides a con-

structive demonstration of the potential of the harm reduction

model as a service-delivery strategy for street youth.

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

11

Clements, K., Gleghorn, A., Garcia, D., Katz, M., & Marx, R. (1997).

A risk profile of street youth in northern California: Implications

for gender-specific human immunodeficiency virus prevention.

Journal of Adolescent Health, 20(5), 343-353.

Most of the youth were heterosexual, white, male, and without

stable housing. Of the total, 60% had had vaginal sex in the

past 30 days; only 44% had used a condom during their most

recent sexual encounter. One third of the sample reported

having injected drugs. Compared with males, females were

equally likely to use injection and noninjection drugs but were

more likely to be sexually active, to have been given a

diagnosis of a sexually transmitted disease, and were less

likely to report consistent condom use. Females without

stable housing were less likely to have used condoms during

their most recent vaginal intercourse. These findings suggest

an urgent need for gender-specific prevention efforts and

increased housing options for youth.

Gleghorn, A.A., Marx, R., Vittinghoff, E., & Katz, M. (in press).

Association between drug use patterns and HIV risks among

homeless, runaway, and street youth in Northern California.

Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

The drug use and HIV risk behaviors of homeless, runaway,

and street youth were compared. Youth who were using any

heroin, speed, or cocaine exhibited more sexual risks than did

youth who were not using; primary stimulant users and those

who used a combination of heroin and stimulants showed

greatest sexual risk. Those who injected combinations of

heroin and stimulants engaged in higher levels of risky

injection practices, including frequent injections and back-

loading syringes, than did primary heroin or primary

stimulant injectors. HIV prevention interventions should be

tailored to drug-use patterns, because youth who use

combinations of heroin and stimulants may require more

intensive services.

AESOP

12

Kipke, M.D., O’Connor, S., Palmer, R., & MacKenzie, R.G. (1995).

Street youth in Los Angeles: Profile of a group at high risk for

human immunodeficiency virus infection. Archives of Pediatric

and Adolescent Medicine, 149(May), 513-519.

Of the youths, 70% were sexually active (average of 11.7 sex

partners during past 30 days). High-risk sex and drug-using

behaviors were prevalent and interrelated in this sample of

urban street youth. Substance-using youth were 3.6 times

more likely to use drugs during sex, 2.2 times more likely to

engage in survival sex, and 2.5 times more likely to report a

sexually transmitted disease. Youth with multiple partners

were more likely to report a previous sexually transmitted

disease and survival sex. New and innovative educational

promotions and prevention interventions for this population

are needed.

Kipke, M.D., Palmer, R.F., LaFrance, S., & O’Connor, S. (1997).

Homeless youths’ descriptions of their parents’ childrearing

patterns. Youth and Society, 28, 415-431.

No one parenting style was associated with homelessness

among the sample. An equal percentage of youth reported

having supportive or emotionally available and having

intrusive or emotionally unavailable parents or caretakers.

However, most of the youth enrolled in this study did report

having parents or caretakers who could be described as

intrusive, emotionally unavailable, detached, and who had

problems with substance use or the law. Gaining a better

understanding of family conflict and its relationship to

homelessness and the behaviors of homeless youth is critically

needed to develop effective prevention interventions as well as

appropriate services.

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

13

Kipke, M.D., Unger, J., O’Connor, S., Palmer, R.F., & LaFrance, S.R.

(1997). Street youth, their peer group affiliation and differences

according to residential status, subsistence patterns and use of

services. Adolescence, 32(127), 655-669.

Five street youth groups were identified: punks and

skinheads, druggies, hustlers, gang members, and loners. The

results demonstrated unique patterns with respect to places

where they stayed or slept, their means of support, and use of

services according to peer group affiliation.

Martinez, T.E., Gleghorn, A., Marx, R., Clements K., Boman, M., &

Katz, M.H. (1998). Psychosocial histories, social environment,

and HIV risk behaviors of injection and noninjection drug using

homeless youths. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 30 (1), 1-10.

Injection drug use is a common risk behavior for HIV infection

among homeless, runaway, and street youth. Youth who

injected drugs were more likely than youth who did not inject

drugs to report traumatic psychosocial histories, including

parental substance use and forced institutionalization, use of

alcohol and other noninjection drugs, a history of survival sex,

and the use of abandoned buildings as shelter. These findings

underscore the need for multifaceted service and prevention

programs to address the varied needs of these high-risk youth.

E

NHANCEMENTS

Cheney, R., & Merwin, A. (1995). Integrating a theoretical

framework with street outreach services: Issues for successful

training. Public Health Reports, 110(Suppl. 1), 1-5.

The authors discuss three key components necessary to

integrate a behavioral research perspective (in this instance,

the stages-of-change model) into the design of outreach

programs: (a) training for successful service delivery, (b)

training for a theory-guided intervention, and (c) feedback and

evaluation. The third component measures the benefits of

staff training to the outreach workers and to their ability to

apply in the field what they have learned.

AESOP

14

Valentine, J., & Wright-DeAgüero, L. (1996). Defining the

component of street outreach for HIV prevention – The contact

and the encounter. Public Health Reports, 111(Suppl. 1), 69-74.

The discussion suggests techniques for enhancing the

encounter between outreach workers and clients by using the

conceptual framework of the social-work helping relationship.

Five elements of the encounter are defined and developed:

screening, engagement, assessment, service delivery, and

follow-up. The encounter represents an enhancement of the

traditional street outreach interaction and a more systematic

approach to promoting the behavioral change goals of AESOP.

M

ETHODS

Clatts, M.C., Davis, W.R., & Atillasoy, A. (1995). Hitting a moving

target: The use of ethnographic methods in the development of

sampling strategies for the evaluation of AIDS outreach

programs for homeless youth in New York City. In E.Y. Lambert,

R.S. Ashery, & R.H. Needle (Eds.), Qualitative methods in drug

abuse and HIV research (NIDA Research Monograph 157, NIH

Publication No. 95-4025). Rockville, MD: National Institute on

Drug Abuse.

This chapter shows how ethnographic methods that include

participant observation and life history interviews were used

as a sampling strategy and a means of obtaining less

accessible information. Interviews included how youth met

everyday needs and consequently how they participated in the

street economy. In addition to identifying important

geographic and temporal gaps in services, the data provided

useful information about a population of youth about whom

little is known.

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

15

O

UTCOME

Gleghorn, A.A., Clements, K.D., Marx, R., Vittinghoff, E., Lee-Chu, P.,

& Katz, M. (1997). The impact of intensive outreach on HIV

prevention activities of homeless, runaway, and street youth in

San Francisco: The AIDS Evaluation of Street Outreach Project

(AESOP). AIDS and Behavior, 1(4), 261-271.

The authors evaluate the impact of an HIV prevention

intervention combining street outreach, storefront prevention

services, and subculture-specific activities for street youth in

intervention and comparison sites before and during

implementation of the intervention. Youth at both types of

sites reported high rates of risky sex and drug-using

behaviors. The intervention did not affect HIV risk behaviors

but was independently associated with increased contact with

outreach workers and increased referrals for services. Higher

levels of contact with outreach workers were associated with

following through with HIV-related referrals and using new

syringes. Youth-oriented needle exchange increased the use of

new syringes.

Greenberg, J., MacGowan, R., Neumann, M.S., Long, A., Fernando,

D., Cheney, R., Sterk, C., & Wiebel, W. (under review). The

relationship between street outreach referrals and accessing

medical services by injecting drug users. Health & Social Work.

This analysis, from 3,237 structured interviews conducted

with injection drug users (IDUs) at five sites between January

1994 and October 1995, examines contact with outreach

workers, the most common medical referrals received and

acted on as a result of this contact, and whether more

frequent contact was associated with increased acting on

medical referrals. Of the IDUs interviewed, 42% to 67% had

talked with an outreach worker in the past 6 months and

reported referrals to a number of medical services, especially

HIV counseling and testing and drug treatment. IDUs with

more than three contacts with outreach workers during the

past 6 months were more likely to seek services. To maximize

the effect of outreach on acting on referrals, training for

outreach workers should address techniques for follow-up

with referred IDUs; identifying and overcoming barriers to

AESOP

16

seeking medical services, especially those for minority clients;

after-care referrals for clients exiting drug treatment

programs; and the importance of treatment for sexually

transmitted diseases in reducing risk for HIV infection.

MacGowan, R.J., Sterk, C.E., Long, A., Cheney, R., Seeman, M., &

Anderson, J.E. (1998). New needle and syringe use and use of

needle exchange programmes by street recruited injection drug

users in 1993. International Journal of Epidemiology, 27, 302-

308.

Street-recruited injection drug users were interviewed in five

U.S. locations in 1993. Most (75% to 95%) reported that it was

easy to get a new syringe. For their most recent injection, 45%

to 77% had used a new syringe, and 2% to 18% had used a

syringe previously used by another injector. The use of needle

exchange programs (NEPs) ranged from 8% to 16% in Chicago,

Philadelphia, and Los Angeles County. Factors associated

with NEP use differed across sites, which suggests that the

dispersion of NEPs and the removal of legal barriers that

restrict access to sterile syringes may be more important to

increasing the use of sterile syringes and NEPs.

Wright-DeAgüero, L.K., Gorsky, R.D., & Seeman, G.M. (1996). Cost

of outreach for HIV prevention among drug users and youth at

risk. Copublished in Drugs and Society, 9 (1/2), 185-197; and

in T. Trotter II (Ed.), Multicultural AIDS prevention programs.

Binghamton, NY: Harrington Park Press.

The authors present the results of a cost analysis at eight sites

that provide outreach services to injection drug users and

street youth. They assessed the potential benefit of HIV

prevention through outreach services by comparing outreach

costs with the costs of treating an HIV-infected person. The

average cost of outreach services was $13.30 per contact.

Costs per contact were 78% higher for street youth than for

drug users. Comparing cost per contact with HIV treatment, if

only 2 in 10,000 outreach contacts reduce their risky behavior

to avoid the transmission of HIV, these programs compare

favorably with other HIV prevention strategies in terms of cost.

17

A PROBABILITY SAMPLING

FOR ASSESSING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF

OUTREACH FOR STREET YOUTH

Michele D. Kipke

*

, Susan O'Connor

*

, Burke Nelson

*

,

and John E. Anderson

†

In 1991, the Division of Adolescent Medicine of Children’s Hospital

Los Angeles received funding from the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC) as part of the cooperative agreement for the

AIDS Evaluation of Street Outreach Projects (AESOP) (CDC, 1993).

The purpose of this project was to conduct research to character-

ize street youth and their involvement in HIV risk-related sex and

drug-using behaviors and to develop, implement, and evaluate the

enhancement of street outreach interventions for this population.

Few studies have evaluated the sex and drug-using behaviors of

urban street youths, and no attempt has been made to systemati-

cally evaluate the effectiveness of outreach activities for this popu-

lation. Furthermore, studies have largely relied on convenience

sampling, which may underestimate the degree to which these

youth are engaging in the kinds of behaviors that put them at risk

for HIV infection. For example, runaway or homeless youth have

been recruited from shelters and drop-in centers (Anderson,

Freese & Pennbridge, 1994; Rotheram-Borus & Koopman, 1991;

Rotheram-Borus et al., 1992).

Convenience sampling can identify only the youth who are using

services; thus, the findings from these studies can be generalized

only to youth who are willing to use such services, not the esti-

mated 65% of runaway or homeless youth who are living on the

streets and not using services (Kipke, O’Connor, Palmer &

LaFrance, 1993). Although probability sampling methods have

*Division of Adolescent Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, Los Angeles,

California

†

Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention–Intervention Research and Support, National

Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia

AESOP

18

been used to survey homeless adults (Burnam & Koegel, 1988;

Robertson, Westerfelt & Irving, 1991), little effort has been made

to apply these sampling methods to homeless youth. To evaluate

the effectiveness of street outreach activities, it was essential to

develop probability sampling methods that enable researchers to

better describe youth, particularly out-of-school and out-of-home

youth who spend most of their time on the streets.

OBJECTIVES AND OVERVIEW OF SAMPLING DESIGN

Our objective was to recruit a sample representative of the target

population (i.e., to develop a method for selecting homeless youth

such that homeless youth at each site would have an equal or a

known probability of being selected for the sample). Numerous

researchers have relied on shelters for their sampling frame. How-

ever, there are several problems with this practice. First, although

some youth stay in shelters, many others move around frequently

and use shelters infrequently, if at all. Second, it is estimated that

there may be 2,000 homeless youth in Los Angeles County at any

time and that 10,000 homeless youth may be on the streets of Los

Angeles during any one year (United Way Planning Council, 1981).

In Los Angeles, approximately 140 shelter beds are available for

this population. Thus, the size of the population exceeds the size

of that shelter system. Finally, there are other services, such as

drop-in and meal services, that are used by a greater proportion of

the homeless youth population and with greater frequency than

are shelter services. Although shelters and drop-in services have

different biases, adding the latter to a sampling frame would

nevertheless be expected to increase the percentage of the total

population covered.

We understood, however, that constructing a sampling frame that

comprised only shelter and drop-in service locations would pose

similar problems. Perhaps the most important bias is that home-

less youth who do not use services would be excluded. Thus,

street and natural hangout locations would need to be included in

the sampling frame in order to identify the homeless youth who

were not using services. Although it is impossible to establish a

sampling frame that would include every homeless youth, we

A PROBABILITY SAMPLING

19

developed a sampling frame that included both service agency and

street locations in an effort to minimize bias and maximize our

ability to survey a wide spectrum of youth who were representative

of the target population.

SAMPLE POPULATION AND TARGET COMMUNITIES

The target population were youth who were 12 to 23 years of age

and who (a) had been living on the streets without their families

for 2 or more consecutive months or (b) were fully integrated into

the "street economy." By definition, youth integrated into the

street economy meet their subsistence needs through one or more

of the following survival strategies: prostitution or survival sex

(defined as the exchange of sex for money, food, a place to stay,

clothes, or drugs), pornography, panhandling, stealing, selling sto-

len goods, mugging, dealing drugs, or engaging in scams or cons.

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in two communities where

runaway or homeless youth were known to congregate: the Holly-

wood area of Los Angeles (the study community, where the

enhanced outreach interventions were introduced) and the down-

town area of San Diego (the control community). In both com-

munities, comparable sampling frames and recruitment strategies

were used to identify and survey street youth for the purpose of

evaluating the effectiveness of enhanced interventions for street

outreach. In this paper, we focus on the Hollywood sampling

frame and sampling units.

CONSTRUCTION OF SAMPLING

The sampling frames were constructed by using information

obtained during the community assessment process (CAP) and

from systematic field observation. The goal of this phase was to

identify high-volume locations and high-frequency times of the

day and days of the week for surveying the target population.

Information from the community assessment and field observa-

tions yielded (a) lists of street corners where the target population

AESOP

20

is known to hang out, (b) other locations where the target popula-

tion could be found (e.g., parks, alleys, restaurants), and (c) agen-

cies that provide shelter and drop-in services.

All service sites for runaway or homeless youth in Hollywood,

including two shelters and five drop-in centers, were included in

the “fixed” sampling frame. Drop-in centers included agencies

that provide day and night drop-in services to street youth in

Hollywood. During a 2-month period, field staff observed and

recorded the number of youth using these services according to

the day of the week and time of day.

Outreach workers and research interviewers conducted open-

ended interviews with street youth and observed street activity in

order to locate street hangouts with the highest number of home-

less youth and to determine the times and days when the volume

was highest. Along the boulevards of Hollywood, these staff first

identified 104 street corners or alleys, 4 parks, and 3 fast-food res-

taurants as potential sampling sites. Large segments of the main

boulevards were broken into 3-block segments. Thus, the number

of natural sites was reduced to 73 street corners, 4 parks, and 3

fast-food restaurants. Once hangouts were defined, field staff

noted street youth activity at these locations throughout the day.

Additional field observation was conducted, by the field research

team and outreach workers from service agencies for youth, in

order to further refine the street sampling frame. (Sample Street

Observation and Summaries of Service Use are in Appendix A.)

Given our broader definition of street youth (i.e., integrated into

the street economy) and the literature, which has largely relied on

samples recruited from shelter and drop-in centers, we chose to

oversample youth from natural and hangout sites by recruiting

70% of the sample from natural sites (thereby oversampling by

20% from these sites) and 30% from fixed sites.

SAMPLING ASSIGNMENTS

A computer program was developed to randomly select and order

locations for interviewing teams (comprising 2 to 4 members).

This program took into account two important aspects of the sam-

A PROBABILITY SAMPLING

21

pling design. First, with evidence that nearly 65% of street youth

are not using services, the selection was weighted to ensure that a

larger proportion of street locations were chosen (70%), thereby

increasing the probability of recruiting youth who were not using

services. Second, all fixed and natural locations in the pool of

potential sampling sites were proportionally weighted on the basis

of the number of youth that typically congregated at that location.

Thus, locations with a higher volume of youth had a greater prob-

ability of being selected by the computer random selection pro-

gram than had locations with lower volumes. Assignments also

were made according to high-frequency times of the day and days

of the week. Assignments were generated weekly.

SAMPLING UNITS AND SELECTION OF RESPONDENTS

F

IXED

S

ITES

Consistent with probability sampling methods used in surveying

homeless adults (Burnam & Koegel, 1988; Robertson, Westerfelt &

Irving, 1991), the overall sampling design for the fixed sites

involved estimating the relative proportions of the homeless youth

population that passed through the shelters and drop-in centers

in a month. These estimates were used to determine the relative

weighting for each agency. Sampling assignments to fixed sites

were weighted according to the type of service and the estimated

proportion of the study population that used the service in a

month (e.g., 13% of the street youth population are believed to use

sheltering services). Thus, in our study the probability of selection

was proportional to the estimated unduplicated number of youth

who used each service in a month. In Hollywood, three shelters

and five drop-in centers were identified.

For respondent selection at each of the fixed sites, interviewers

first reviewed the agency's sign-in roster to determine how many

youth were in the agency. Interviewers then randomly selected

potential respondents from the agency sign-in sheet. They used a

predetermined random start number and began selecting respon-

dents by using a sampling fraction (i.e., the number of youth to

count off, beginning with the random start-numbered youth on

the agency list). Going down the list, interviewers then selected

AESOP

22

additional youth on the list according to the sampling fraction.

The sampling fraction was determined by dividing the number of

youth signing into the agency by the number of interviewers; the

number of youth selected equaled the number of interviewers (see

the Sampling Fraction Table, Appendix B).

Interviewers then asked the intake worker to introduce them to

the selected respondents. If a potential respondent declined to

participate in the study, a new respondent was selected by choos-

ing the next consecutive youth on the list after the one who

declined. Replacement continued in this manner until all appro-

priate respondents were selected and agreed to be interviewed.

N

ATURAL

S

ITES

During the initial community assessment, teams compiled an

exhaustive list of natural street locations and hangouts along five

boulevards within a 12-square mile area of Hollywood. In select-

ing respondents, interviewer teams first determined the number of

potential respondents at a site specified by the sampling assign-

ment (i.e., in a block segment, on the street corner, in the alley or

park) by counting the number of youth who seemed to be 12 to 24

years of age at the location. They then determined the sampling

fraction by looking at the sampling fraction table and locating the

fraction that corresponded with the total number of youth counted

at that site. For example, if there were two interviewers and 10

potentially eligible youth at the site, the sampling fraction would

be 1/5. Youth were "counted out" (from left to right), starting from

a predetermined random start number and selected according to

the sampling fraction (see Appendix B). If the number of potential

respondents was equal to or fewer than the number of interview-

ers, all youth were approached and asked to complete a screening

instrument. As in sampling in fixed sites, a youth who refused to

participate in the study was replaced by the next consecutive

youth after the one who declined. On the street, this means

selecting the youth nearest and to the right of the refuser. Youth

who entered the sampling site after the initial selections were not

approached for recruitment.

A PROBABILITY SAMPLING

23

DISCUSSION

There are a number of advantages and disadvantages in using a

probability sampling design for street-based epidemiologic

research. Perhaps one of the greatest disadvantages is the cost

associated with developing and implementing such a design. A

community assessment of service agencies is required to estimate

accurately the number of youth who are using services. Extensive,

systematic field observations are required to initially identify natu-

ral sites. Relative weightings are then constructed on the basis of

population estimates. Ongoing observations are then required to

monitor the field to ensure that new hangouts are added and that

low-volume sites are continually dropped from the sampling

frame. Finally, this sampling design requires a greater amount of

time for recruitment and interviewing than would be required by

convenience sampling.

There are, however, clear advantages in using probability sam-

pling. Research involving representative samples of runaway or

homeless youth, particularly youth who are not using services,

has been greatly needed. These results can be generalized to the

larger street youth population of a study area. Probability sam-

pling is perhaps the best method for obtaining samples represen-

tative of the target population, hence for accurately estimating

population characteristics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, cooperative agreement U62/CCU907198. The views

expressed are those of the authors, not necessarily the funding

agency. Special thanks go to Judith Greenberg, Steven R.

LaFrance, Richard MacKenzie, Susanne Montgomery, Marjorie

Robertson, and members of the Los Angeles research team

(Michael Cohen, Marcus Kuiland-Nazario, Raymond Palmer, Sara

Parker, Audruin Pittman, German Rodriguez, and Lily Rodriguez).

AESOP

24

References

Anderson, J., Freese, T., & Pennbridge, J. (1994). Sexual risk

behavior and condom use among street youth in Hollywood.

Family Planning Perspectives, 26(1), 22-26.

Burnam, M.A., & Koegel, P. (1988). Methodology for obtaining a

representative sample of homeless persons: The Los Angeles

Skid Row Study. Evaluation Review, 12, 117-152.

CDC. (1993). Assessment of street outreach for HIV prevention—

Selected sites, 1991-1993. MMWR, 42(45), 873, 879-880.

Kipke, M.D., O'Connor, S.L., Palmer, R., & LaFrance, S. (1993,

October). Street youth, outreach and HIV risk: Facing the

challenge in two communities. Presented at American Public

Health Association meeting, San Francisco, CA.

Robertson, M.J., Westerfelt, A., & Irving, P. (1991, November).

Research note: The impact of sampling strategy on estimated

prevalence of major mental disorder among homeless adults in

Alameda County, CA. Presented at American Public Health

Association meeting, Atlanta, GA.

Rotheram-Borus, M.J., & Koopman, C. (1991). Sexual risk beha-

viors, AIDS knowledge, and beliefs about AIDS among run-

aways. American Journal of Public Health, 81, 208-210.

Rotheram-Borus, M.J., Meyer-Bahlburg, H.F.L., Rosario, M.,

Koopman, C., Haignere, C.S., Exner, T.M., Matthieu, M.,

Henderson, R., & Gruen, R.S. (1992). Lifetime sexual beha-

viors among predominantly minority male runaways and gay/

bisexual adolescents in New York City. AIDS Education and

Prevention, (Suppl. Fall), 34-42.

United Way Planning Council. (1981). Runaway youth situation in

Los Angeles County: A general overview. Los Angeles: The

United Way.

APPENDIX A

25

APPENDIX A

SAMPLE STREET OBSERVATION AND

S

UMMARIES OF SERVICE USE

STREET OBSERVATION SUMMARY

Hollywood Boulevard

10:00am

11:00 am

Noon

1:00 pm

2:00 pm

3:00 pm

4:00 pm

5:00 pm

6:00 pm

7:00 pm

Totals

Sycamore 2 2 0103

8

Orange 0 0 2010 3

Orchid 0 4 0320 9

Hillcrest 0 0 0006 6

Highland 3 5 2005 15

McDonald’s 2 4 0354 18

McCadden 0 1 3010 5

Las Palmas 0 7 0018 16

Cherokee 0 0 0047 11

Whitley 1 0 0000 1

Tomy’s 2 0 2313 11

Hudson 0 2 0317 13

Wilcox 0 0 0406 10

Cahuenga 0 0 0003 3

Ivar 2 2 1020 7

Vine 0 5 0003 8

El Centro 0 0 0200 2

Gower 2 2 0010 5

No. Sheets 3 4 0 1323

Totals 14 34 0 10 19 19 55

AESOP

26

HOLLYWOOD DROP-IN CENTERS

SUMMARY OF HIGH-VOLUME TIMES AND DAYS

Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center (GLCSC)

NOTES: I called GSCSC at 1:30 on 10/22, and there were 3 youth in the agency. I

was told that 2 to 5 had been in the agency all day. I suggest that we do not use

GLCSC as a fixed site for interviewing.

9:00 am

10:00 am

11:00 am

Noon

1:00 pm

2:00 pm

3:00 pm

4:00 pm

5:00 pm

Totals

Thu 10/1 220000110 6

Fri 10/2 51202210013

Mon 10/5 34411010014

Tue 10/6 131011100 8

Wed 10/7 31403210014

Thu 10/8 123020000 8

Fri 10/9 23104221015

Mon 10/12 41521010014

Tue 10/13 42205112017

Wed 10/14 41300113013

Thu 10/15 10601221013

Totals 30 20 31 3 20 11 12 8 0

APPENDIX A

27

Los Angeles Youth Network

NOTES: I called LAYN at 2:00 on 10/22, and there were 10 youth in the agency. I

was told that there had been many more earlier in the day but that most had gone

to the YMCA. I suggest that we use LAYN as a fixed site interiew location on Mon-

days and Wednesdays, any time between noon and 4:00pm.

9:00 am

10:00 am

11:00 am

Noon

1:00 pm

2:00 pm

3:00 pm

4:00 pm

5:00 pm

Totals

Thu 10/8 1546453200 39

Fri 10/9 1354323400 34

Mon 10/12 1837226240 44

Tue 10/13 1275231250 37

Wed 10/14 1812642550 43

Thu 10/15 1312362320 32

Totals 89 21 26 20 22 17 18 16 0

AESOP

28

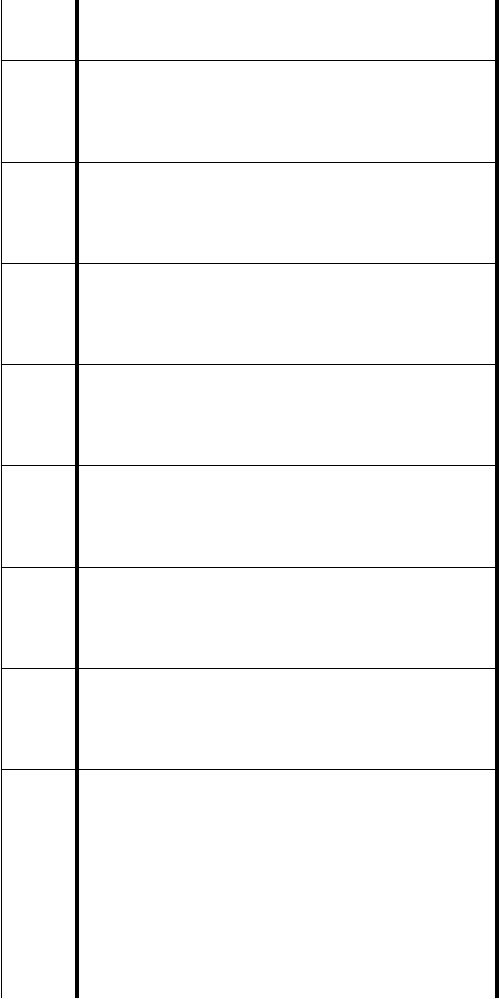

APPENDIX B

SAMPLING FRACTION TABLE

AIDS Evaluation of Street Outreach Project

Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles

Street Locations Agencies

No. of

Youth

No. of

Intercepts Fraction

No. of

Youth

No. of

Intercepts Fraction

1 1 1/1 1 1 1/1

2 2 1/1 2 2 1/1

3 2 1/2 3 3 1/1

4 2 1/2 4 4 1/1

5 2 1/3 5 4 1/2

6 2 1/3 6 4 1/2

7 2 1/4 7 4 1/2

8 2 1/4 8 4 1/2

9 2 1/5 9 4 1/3

10 2 1/5 10 4 1/3

11 2 1/6 11 4 1/3

12 2 1/6 12 4 1/3

13 2 1/7 13 4 1/4

14 2 1/7 14 4 1/4

15 2 1/8 15 4 1/4

16 2 1/8 16 4 1/4

17 2 1/9 17 4 1/5

18 2 1/9 18 4 1/5

19 2 1/10 19 4 1/5

20 2 1/10 20 4 1/5

21 2 1/11 21 4 1/6

22 2 1/11 22 4 1/6

23 2 1/12 23 4 1/6

24 2 1/12 24 4 1/6

25 2 1/13 25 4 1/7

29

A STORYTELLING MODEL

USING PICTURES FOR HIV PREVENTION

WITH INJECTION DRUG USERS

Anna Long

*

, Judith Greenberg

†

, Gladys Bonilla

*

,

and Ronald Weathers

*

The importance of storytelling in the modeling of behavior and

teaching people about their lives has been extensively addressed

by the late Joseph Campbell, a foremost authority on mythology

(most recently, Campbell, 1988). Empirical research in the self-

help community also suggests the importance of personal stories.

Rappaport (1993) compared the personal stories told during meet-

ings of a mutual help group for mentally ill persons with the sto-

ries told by patients receiving professional care for mental illness.

The first group saw themselves as a part of a “caring and sharing”

community and as givers as well as receivers who hoped for posi-

tive change. By contrast, the patients’ stories “often revolve

around learning to see one’s self as sick and dependent on medi-

cation to control behavior.” Similarly, the stories that people tell

about their lives in groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA)

permit the members to take on the ideology of the group as part of

their personal identities. Telling stories of “hitting bottom” and of

recovery serve as testimony to the importance of the AA philoso-

phy of sobriety (Bean, 1975).

Using this storytelling framework, investigators in Los Angeles

County, one of eight AESOP sites, developed a unique outreach

intervention strategy. Injection drug users (IDUs) were encour-

aged to tell their own stories about risk behaviors to outreach

workers after looking at a series of abstract illustrations related to

themes of risk and risk-prevention behaviors for acquiring HIV.

These illustrations were produced by a local Los Angeles artist,

*Office of AIDS Programs and Policy, Los Angeles County Department of Health

Services, Los Angeles, California

†

Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia

AESOP

30

whose grasp of the street drug culture was translated into draw-

ings that were used to encourage people to discuss risky sex and

drug-using behaviors.

CHOOSING THE STORYTELLING INTERVENTION

F

ORMATIVE

RESEARCH

The AESOP project began with a two-part formative study to guide

the identification of specific risk-reduction needs and correspond-

ing interventions for IDUs in Los Angeles County. Using data from

various sources (research on IDUs conducted in the county, epide-

miologic and drug-use data), we described the IDU population,

reported what was known about their risk behaviors, and specified

the current outreach programs that addressed their HIV risk-

reduction needs.

That initial overview revealed considerable variation in the num-

ber and the demographic characteristics of IDUs in the different

parts of the county. The IDUs were as diverse in their cultural

and ethnic backgrounds as the county’s 4,083 square miles are in

their geographic features. There were also variations in the pro-

grams that community-based organizations had developed to

respond to the needs of IDUs in their particular communities.

The community assessment process (CAP) constituted the second

part of the formative research. These activities focused on develop-

ing more current insight into the IDU population through in-depth

interviews with IDUs themselves; outreach workers; agency repre-

sentatives with knowledge of the IDU community, such as social

service workers and law enforcement officers; and persons who

interact with IDUs but are not part of the formal service delivery

system, such as shopkeepers, taxi drivers, and hotel clerks. The

interviews were focused on IDUs’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs

about HIV; sex and drug-using behaviors of IDUs and their risks

for HIV infection; risk-reduction practices of IDUs; assessment of

services used by IDUs; barriers and facilitators to service use; and

ideal intervention strategies.

A STORYTELLING MODEL

31

The CAP revealed the range of risk behaviors of the target popula-

tion. It showed that (a) despite considerable knowledge about HIV,

most IDUs required additional information and strategies that

would help them consistently practice appropriate risk-reduction

behaviors; (b) uniformity was lacking in attitudes toward and

intentions to reduce their risk for HIV; and (c) IDUs would not

change their risk behaviors, regardless of the information they

had about HIV, until they were ready. The notion of readiness

that echoed in many of the CAP interviews was a key factor in our

selecting the stages-of-change model from behavioral theory

(Prochaska & DiClemente, 1986, 1992; Prochaska, DiClemente &

Norcross, 1992) to help us develop the interventions. Finally, out-

reach workers and IDUs indicated a need for materials that would

be suitable for the prevention needs of different groups.

Overall, the formative research revealed that the proposed inter-

ventions should be (a) adaptable to the ethnic, cultural, and lin-

guistic diversity of Los Angeles County IDUs; (b) inexpensive and

reproducible enough to maximize the possibility of adoption by

outreach programs that serve IDUs; (c) comprehensive enough to

address the needs of IDUs across a spectrum of HIV awareness

and risk-reduction practices; (d) accessible enough to facilitate

HIV counseling and testing on-site; and (e) able to provide feed-

back on whether IDUs sought the services to which they were

referred.

Using the formative research, we designed an intervention with

three components: (a) storytelling allowing the outreach worker to

help the IDU recognize personal HIV risk behaviors and learn

about or reinforce intentions to reduce risk behaviors; (b) a referral

tracking system to help outreach workers follow up on the IDUs’

use of the services to which they were referred; and (c) an outreach

worker-administered HIV testing program that facilitated finger-

sticks on the street to enable outreach workers to test a target

population reluctant to seek this service in clinical settings.

R

ATIONALE

FOR

S

TORYTELLING

During the formative research, we routinely observed the setting

in which outreach workers delivered their services to IDUs. One

observation, consistent throughout the county, concerned the use

AESOP

32

of pictures as a common method of communicating ideas in the

communities where outreach was conducted. In many communi-

ties, particularly communities of color, murals, usually painted by

local artists, adorned the walls of public and private buildings,

cinder-block fences, and freeway overpasses. These murals

tended to be colorful, highly complex, and symbolic. Thus, the

use of visual art in the communities where outreach was con-

ducted was viewed as an important consideration in designing the

intervention. The fact that many IDUs mentioned the need for

new materials or for materials that better reflected their communi-

ties also influenced the design and format of the visuals. The need

for HIV interventions with an emphasis on cultural appropriate-

ness has been documented (Stevenson, McKee & Josar, 1995;

Weeks, Schensul, Williams, Singer & Grier, 1995). It was deter-

mined that the required pictures needed to be complex enough to

engage the viewer, to stimulate introspection, and to span the eth-

nic and cultural diversity of Los Angeles County IDUs. We

excluded written messages from the visuals so that the outreach

worker and IDU dyad could work together to develop a story for

each picture.

In contrast to the generic role-model stories used in CDC’s com-

munity demonstration projects for HIV prevention (McAlister,

1997), storytelling allowed the IDUs, assisted by outreach work-

ers, to generate their own stories from a set of illustrations. The

IDUs’ stories often told of specific risk behaviors that the IDU

might have been engaging in, the consequences of these behav-

iors, and risk-reduction strategies to be reinforced by the outreach

worker. The outreach worker would begin by asking the IDU what

was happening in a particular picture. Three key sentences were

used to help the IDU: “Tell me what is happening in the picture.”

“What are the people doing?” “What are they saying?”

R

ELATIONSHIP

OF

THE

S

TORYTELLING

M

ODEL

TO

L

EVEL

OF

S

TAGE

OF

C

HANGE

The storytelling also allowed the project to incorporate the theoret-

ical foundation of the stages-of-change model. Outreach workers

used the storytelling as a prelude to questions that specified each

of the five stages of change through which people typically

progress when changing behaviors: precontemplation, contempla-

A STORYTELLING MODEL

33

tion, ready-for-action, action, or maintenance. (See Fishbein and

Rhodes [1997] for how the stages-of-change model can be applied

in HIV prevention.) Once the clients had been placed in one of the

five stages, a clear and succinct risk-reduction message appropri-

ate for that stage was given.

DEVELOPING THEMES FOR STORYTELLING ILLUSTRATIONS

Because the formative research showed that condoms and bleach

continued to be used inconsistently, we designed the illustrations

to address three specific risk-reducing behaviors: (a) consistent

use of condoms, (b) consistent use of new injection equipment,

and (c) consistent bleaching of shared injection equipment. A

multistage process, drawing on the in-depth interviews with IDUs

in the second part of the formative research, was used to produce

the illustrations: (a) determining the IDUs’ view of the behaviors

that placed them at risk of contracting HIV; (b) identifying themes

in IDUs’ open-ended responses associated with risk-taking behav-

iors; (c) rating these themes for importance and applicability to

IDUs, by a sample of IDUs and outreach workers; (d) selecting

risk-behavior themes on which to focus the illustrations; (e) identi-

fication of an appropriate artist; (f) repeatedly testing sketches

with IDUs and then refining the illustrations; (g) producing final

illustrations; (h) training outreach workers to use the illustrations;

and (i) implementing and evaluating the intervention (see List 1).

Using the information from the CAP in-depth interviews with

IDUs, we selected 40 narrative themes. Many were the verbatim

statements of active IDUs. A convenience sample of 20 IDUs from

two communities closest to where the AESOP research would be

conducted and the outreach staff (10 in all) at two agencies serv-

ing these communities were asked to rate each of the 40 narrative

themes on three scales: (a) the degree to which the theme was

applicable to their community of IDUs; (b) the degree to which the

theme was important to their community; and (c) whether or not

the theme should be included in new materials. Feedback from

outreach workers was important because of their expertise in

working with the target population. On the basis of this review, sex

and drug themes were prioritized for inclusion in the illustrations.

AESOP

34

LIST 1

D

EVELOPING ILLUSTRATIONS FOR INTERVENTION

Characteristics of Ideal Intervention

1. Adaptable to multiple cultures and languages

2. Flexible to address clients’ range of needs and

preparedness

3. Inexpensive and easy to reproduce

Steps in Appropriate Interventions

1. Collect formative information on clients’ needs

and current interventions.

2. Use the comprehensive baseline report of HIV

epidemiology and drug use.

3. Conduct a community assessment of IDUs and

service agencies.

Development of Visuals

1. Survey IDUs to determine their perceived HIV

risk behaviors.

2. Recognize themes from IDUs open-ended responses.

3. Rate IDU themes by IDUs and outreach workers.

4. Select major risk-behavior themes.

5. Select and orient an artist.

6. Repeat field testing and refine illustrations.

7. Produce final illustrations.

8. Train outreach workers.

9. Implement and evaluate.

A STORYTELLING MODEL

35

P

RIORITY

T

HEME

FOR

S

EXUAL

B

EHAVIOR

The sex theme given highest priority by IDUs and outreach work-

ers was "My woman would be offended if I started talking about

condoms." This theme had been a consistent issue not only for

male but also for female IDUs and may have been related to the

lack of condom use during vaginal sex with main partners that

was consistently recorded in the Los Angeles AESOP survey data.

Conversations with IDUs and outreach workers had indicated that

(a) male IDUs were frequently concerned about using condoms

with their main partners because their partners might become

suspicious about their fidelity; (b) female IDUs were not always in

control of the decision to use condoms with main partners,

although they might have more control in using condoms with

casual partners; and (c) both men and women were concerned

about their partner’s possible reaction to their request to use con-

doms. Possibilities for addressing this theme in the storytelling

intervention were (a) increasing men's and women's awareness

that their partners may be equally concerned about the other's

perceptions of suggestions to use condoms and (b) modeling skills

used to discuss and negotiate condom use.

P

RIORITY

T

HEME

FOR

I

NJECTION

B

EHAVIOR

The injection theme that received the highest priority rating from

IDUs and outreach workers was “I use my own outfit [injection

equipment] most of the time.” The baseline survey data supported

this statement. Data indicated that most respondents had used a

brand-new outfit for their most recent injection or one that had

not been used by anyone else. However, 21% reported using a

shared needle "sometimes," "almost every time," or "every time"

they injected. Two of the remaining five priority themes related to

the availability of bleach or new injection equipment were "When

I'm sick, I can't waste time looking for bleach or a new outfit" and

"What do you do when there is no bleach around?"

Providing users with strategies for dealing with the theme of using

one’s own outfit most of the time was an important focus of the

storytelling model. The strategies included (a) reinforcing sole use

of an outfit; (b) reinforcing the desire to avoid situations in which

outfits are used by a group; and (c) examining other situations

AESOP

36

related to sharing, specifically, sharing when experiencing symp-

toms of withdrawal and sharing when one’s outfit is blocked or

otherwise nonfunctional, and developing strategies to avoid inject-

ing in those situations.

PRODUCING ILLUSTRATIONS

S

ELECTING

THE

A

RTIST

The intervention required the services of an artist who could pro-

duce illustrations similar to the indigenous art produced through-

out the county and who could visually represent the complexity of

the messages selected for focus. Once an artist whose work gener-

ated a similar feeling of depth, complexity, and engagement had

been found, the next challenge was to explain to the artist the

need for the materials and the messages to be conveyed.

We took him through a process to increase his understanding of

the risk behaviors that the target population engaged in and of the

barriers to risk reduction that IDUs faced. First, a session was

held to familiarize the artist with the statistics on Los Angeles

County IDUs. This included a discussion of the diversity of the

target population, variation in risk behaviors, and the critical

problems of the IDUs contacted during outreach. Second, written

stories based on the two priority themes were provided to the art-

ist to help him understand the narrative themes.

Several sketches were produced for the "I Don't Share" message.

It was determined that the needle-sharing message would require

three pictures to convey its complexity. The artist, using informa-

tion about risk behaviors and barriers to reduction, developed

three sketches.

I

NVOLVING

THE

T

ARGET

P

OPULATION

AND

F

INE

-T

UNING

THE

I

LLUSTRATIONS

The rough black-and-white sketches were taken into the field for

testing with current IDUs. Two sites afforded a setting amenable

to in-depth interviews with the IDUs. IDUs were shown one

A STORYTELLING MODEL

37

sketch and asked to tell the interviewer what was happening in

the picture. Stories and explanations by the IDUs were analyzed

for content by members of the AESOP staff. The three injection-

related illustrations generated stories that were surprisingly close

to the messages that had been selected for focus. From the pre-

liminary sketches, the artist painted watercolor versions to be

tested in the field.

Testing the watercolors indicated a need to adjust the colors, not

only for emphasis of specific aspects of the illustration but also to

reflect the multicultural setting in Los Angeles. Several flesh

tones were thus used for the people in the pictures. Some figures

were presented as neither male nor female to allow outreach work-

ers to use the illustrations to depict individuals of either sex and

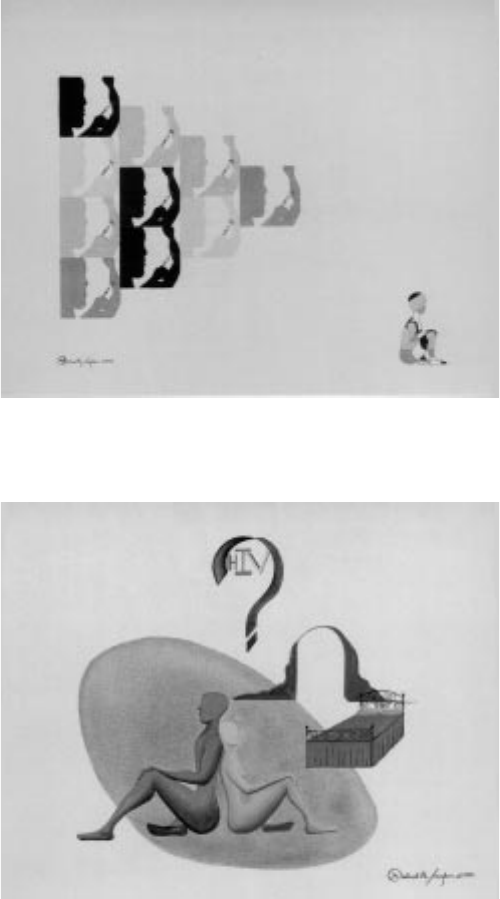

of any ethnicity (see Figures 1, 2, and 3).

Although completing the three illustrations that addressed differ-

ent aspects of the “I don’t share message” was relatively simple, it

proved difficult to make an appropriate illustration to address sex-

related risk behaviors. The initial sketches presented to AESOP

staff members were either too broad or did not focus on HIV. One

sketch presented to the target population, although it addressed

the complexity of sex-related risk behaviors, did not focus suffi-

ciently on HIV. A second sketch, much closer to the original "Not

with my man or woman" story, still did not focus attention on HIV.

Despite the initial intention to exclude text from the visuals, it was

determined that the word HIV needed to be added to the final

sketch. With the addition of HIV, the message became very clear

to the IDUs who tested the illustration (see Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Source for illustrations: Michael Taylor, Los Angeles, copyright 1994

AESOP

40

TRAINING OUTREACH WORKERS

TO USE STORYTELLING AND ILLUSTRATIONS

Several factors were considered in designing the outreach worker

training. It was clear from the field observations and formative

research data that some outreach workers were reluctant to use

new methods to reach clients. Many outreach workers had been

in the forefront of responding to the HIV/AIDS crisis early in the

epidemic and considered their background and experience in pro-

viding street outreach services to IDUs more applicable than the

interventions developed by researchers. There was a strong con-

cern that research-based interventions simply "would not work" in

the field. It was clear that the training would need to build upon

workers’ current wealth of knowledge rather than attempting to

supplant their tools and talents with new interventions.

Moreover, to move from the storytelling model to staging clients for

risk-reduction messages, outreach workers required working

knowledge of the theoretical foundation of the interventions. Thus,

outreach workers needed to be trained to use the pictures on the

street, both to elicit risk-behavior information and to teach and

reinforce risk-reduction behaviors. It was decided that two train-

ing sessions would be held—the first on the use of the illustra-