DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES

POLICY DEPARTMENT C: CITIZENS' RIGHTS AND

CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS

LEGAL AFFAIRS

Legal Instruments and Practice of

Arbitration in the EU

ANNEXES

PE 509.988 EN

DOCUMENT REQUESTED BY THE COMMITTEE ON LEGAL AFFAIRS

AUTHOR(S)

Mr Tony COLE (Principal Investigator)

Mr Ilias BANTEKAS (Investigator)

Mr Federico FERRETTI (Investigator)

Ms Christine RIEFA (Investigator)

Ms Barbara WARWAS (Researcher/Drafter/Administrator)

Mr Pietro ORTOLANI (Researcher/Drafter)

RESPONSIBLE ADMINISTRATOR

Mr Udo BUX

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

European Parliament

B-1047 Brussels

E-mail: poldep-c[email protected].eu

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

ABOUT THE EDITOR

Policy Departments provide in-house and external expertise to support EP committees and

other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny.

To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe to its monthly newsletter please write to:

poldep-citizens@ep.europa.eu

European Parliament, manuscript completed in November 2014.

© European Union, Brussels, 2014.

This document is available on the Internet at:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/studies

DISCLAIMER

The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and do

not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the

source is acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy.

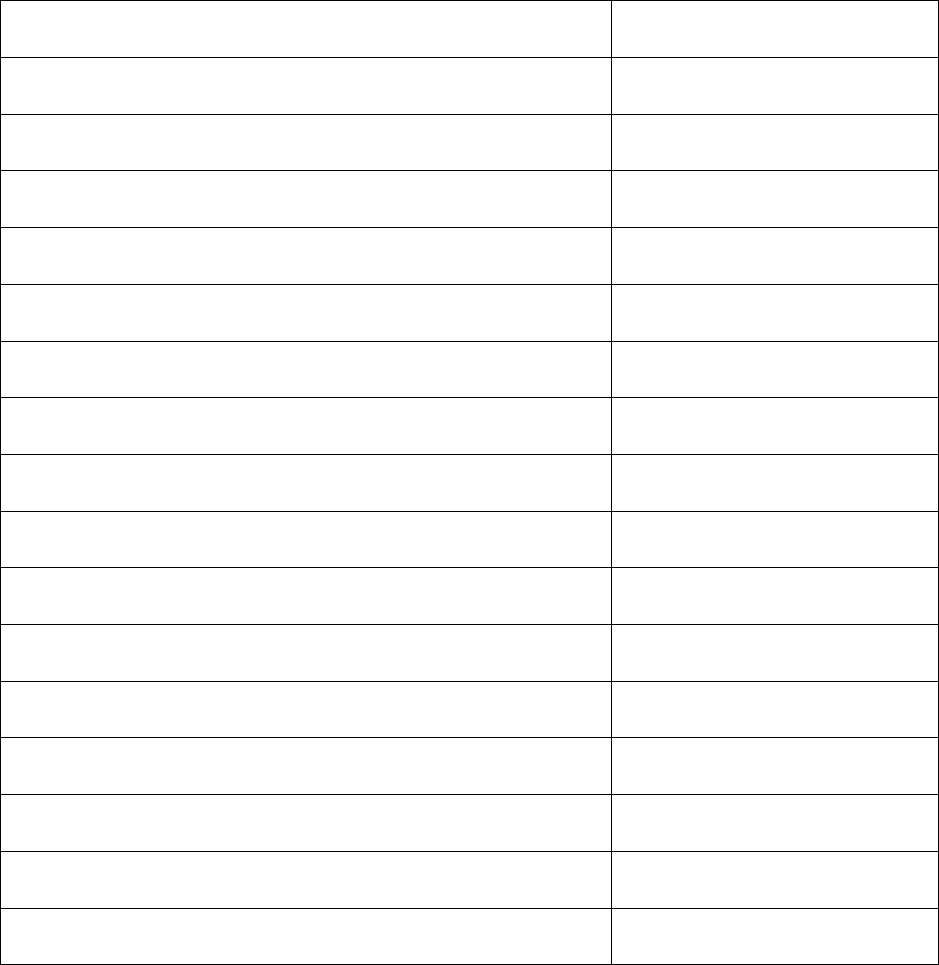

CONTENTS

1. ANNEX A–ARBITRATIONS INVOLVING MEMBER STATES/SWITZERLAND, STATE

ENTITIES AND THE EUROPEAN UNION SINCE 1999 .............................................5

1.1. STATES AND STATE ENTITIES IN ARBITRATIONS OTHER THAN INVESTMENT

ARBITRATIONS, STATE-STATE ARBITRATIONS, AND WTO ARBITRATIONS ..........5

1.2. INVESTMENT ARBITRATIONS, STATE-STATE ARBITRATIONS, AND WTO

ARBITRATIONS............................................................................................9

1.2.1. AUSTRIA ................................................................................................ 9

1.2.2. B

ELGIUM ................................................................................................ 9

1.2.3. B

ULGARIA............................................................................................... 9

1.2.4. C

ROATIA ................................................................................................ 9

1.2.5. C

YPRUS................................................................................................ 10

1.2.6. C

ZECH REPUBLIC.................................................................................... 10

1.2.7. D

ENMARK ............................................................................................. 11

1.2.8. E

STONIA .............................................................................................. 11

1.2.9. F

INLAND .............................................................................................. 11

1.2.10. F

RANCE................................................................................................ 11

1.2.11. G

ERMANY ............................................................................................. 12

1.2.12. G

REECE ................................................................................................ 12

1.2.13. H

UNGARY ............................................................................................. 12

1.2.14. I

RELAND .............................................................................................. 13

1.2.15. Italy................................................................................................... 13

1.2.16. L

ATVIA ................................................................................................ 13

1.2.17. Lithuania............................................................................................ 14

1.2.18. Luxembourg....................................................................................... 14

1.2.19. Malta.................................................................................................. 14

1.2.20. Netherlands ....................................................................................... 14

1.2.21. Poland ............................................................................................... 14

1.2.22. Portugal ............................................................................................. 15

1.2.23. Romania ............................................................................................ 15

1.2.24. Slovak Republic ................................................................................. 16

1.2.25. Slovenia ............................................................................................. 16

1.2.26. Spain ................................................................................................. 16

1.2.27. Sweden .............................................................................................. 17

1.2.28. United Kingdom ................................................................................. 17

1.2.29. Switzerland ........................................................................................ 17

1.2.30. European Union (formerly European Communities) ........................... 18

2. ANNEX B – KEY FEATURES OF NATIONAL ARBITRATION LAW IN THE

MEMBER STATES AND SWITZERLAND ............................................................1

2.1. A

USTRIA ...............................................................................................1

2.2. B

ELGIUM ...............................................................................................5

2.3. B

ULGARIA..............................................................................................8

2.4. C

ROATIA .............................................................................................14

2.5. C

YPRUS .............................................................................................18

2

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

2.6. C

ZECH REPUBLIC .................................................................................21

2.7. DENMARK ..................................................................................................... 25

2.8. E

NGLAND...................................................................................................... 30

2.9. E

STONIA ...................................................................................................... 35

2.10. F

INLAND ...................................................................................................... 38

2.11. F

RANCE........................................................................................................ 43

2.12. G

ERMANY ..................................................................................................... 48

2.13. G

REECE........................................................................................................ 53

2.14. H

UNGARY ..................................................................................................... 58

2.15. I

RELAND ...................................................................................................... 63

2.16. I

TALY ........................................................................................................ 67

2.17. L

ATVIA ........................................................................................................ 74

2.18. L

ITHUANIA ................................................................................................... 78

2.19. L

UXEMBOURG ................................................................................................ 83

2.20. M

ALTA ........................................................................................................ 87

2.21. N

ETHERLANDS ............................................................................................... 93

2.22. P

OLAND ....................................................................................................... 99

2.23. P

ORTUGAL .................................................................................................. 104

2.24. R

OMANIA ................................................................................................... 109

2.25. S

COTLAND .................................................................................................. 115

2.26. S

LOVAKIA................................................................................................... 121

2.27. S

LOVENIA................................................................................................... 125

2.28. S

PAIN ...................................................................................................... 129

2.29. S

WEDEN..................................................................................................... 135

2.30. S

WITZERLAND ............................................................................................. 140

REFERENCES...........................................................................................146

3. ANNEX C – A

RBITRAL INSTITUTIONS QUESTIONNAIRES ..............................1

3.1. A

RBITRATION AND MEDIATION CENTRE OF PARIS (CMAP) ...........................1

3.2. A

RBITRATION INSTITUTE OF THE FINLAND CHAMBER OF COMMERCE................4

3.3. A

RBITRATION INSTITUTE OF THE STOCKHOLM CHAMBER OF COMMERCE (SCC) ........8

3.4. B

ARCELONA ARBITRATION COURT (TAB) ................................................14

3.5. B

ELGIAN CENTRE FOR MEDIATION AND ARBITRATION (CEPANI).................18

3.6. C

ENTRE FOR EFFECTIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION (CEDR)..............................21

3.7.

C

HAMBER OF ARBITRATION OF MILAN .....................................................24

3.8. C

IVIL AND MERCANTILE COURT OF ARBITRATION (CIMA) ..........................29

3.9. C

OURT OF ARBITRATION ATTACHED TO THE HUNGARIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

AND

INDUSTRY....................................................................................32

3.10. C

OURT OF ARBITRATION OF THE ESTONIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE AND

INDUSTRY ..........................................................................................37

3.11. C

OURT OF ARBITRATION OF THE HAMBURG CHAMBER OF COMMERCE .............40

3.12. C

OURT OF ARBITRATION OF THE POLISH CHAMBER OF COMMERCE.................43

3.13. C

YPRUS ARBITRATION & MEDIATION CENTRE (CAMC) ..............................49

3.14. D

ANISH INSTITUTE OF ARBITRATION ......................................................53

3.15. D

EPARTMENT OF ARBITRATION, ATHENS CHAMBER OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY.... 57

3.16. DIS (G

ERMAN INSTITUTE OF ARBITRATION) ............................................63

3

3.17. I

NTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR DISPUTE RESOLUTION ..................................67

3.18. I

TALIAN ASSOCIATION FOR ARBITRATION................................................74

6.30. L

ONDON COURT OF INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAITON (LCIA) .........................77

3.19. L

ONDON MARITIME ARBITRATORS ASSOCIATION.......................................82

3.20. M

ADRID COURT OF ARBITRATION (CAM) ................................................85

3.21. M

ALTA ARBITRATION CENTRE ................................................................90

3.22. N

ETHERLANDS ARBITRATION INSTITUTE.................................................. 93

3.23. P

ERMANENT ARBITRATION COURT OF THE SLOVAK BANKING ASSOCIATION ....97

3.24. S

COTTISH ARBITRATION CENTRE..........................................................100

3.25. S

PANISH COURT OF ARBITRATION (CEA) ..............................................103

3.26. S

WISS CHAMBERS' ARBITRATION INSTITUTION ......................................107

3.27. V

ENICE CHAMBER OF ARBITRATION ......................................................110

3.28. V

IENNA INTERNATIONAL ARBITRAL CENTRE ...........................................114

3.29. V

ILNIUS COURT OF COMMERCIAL ARBITRATION (VCCA) ..........................118

REPORTERS ............................................................................................123

4

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

1. Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/ Switzerland,

State Entities and the European Union Since 1999

This Annex lists all identified arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State

Entities and the European Union where a decision occurred from January 1

st

, 1999 up

through August 2014. It must be emphasised that because of the confidentiality involved in

much arbitration no list of this type can be exhaustive, and so it is unavoidable that further

arbitrations will exist beyond those listed below.

1.1. States and State Entities in Arbitrations other than

Investment Arbitrations, State-State Arbitrations, and WTO

Arbitrations

While the remainder of this Annex will list by name arbitrations in which States or State

Entities have been involved, this information is much more difficult to generate about

commercial arbitrations and other arbitrations that do not fit into the categories used in

Section 4.2. Such arbitrations are often undertaken confidentially, meaning that no

information is publicly available on even the existence of the arbitration, or where its

existence is known, on the specific parties involved.

For this reason it was decided that a list of known arbitrations of this type would provide a

misleading picture of the involvement of States, Parastatal or Public Entities in arbitration.

As a more useful measure, information was gathered from European arbitral institutions

regarding the number of arbitrations they have administered over the past 5 years, the

percentage of those arbitrations that were Investment Arbitrations or State-State

Arbitrations (WTO Arbitrations not being administered by independent arbitral institutions),

and the percentage that involved States, Parastatal or Public Entities. This information was

requested in a broader questionnaire supplied to all the primary arbitral institutions in the

European Union. The responses of those institutions that provided this data is reproduced

below, with an estimate of the number of arbitrations involving States, Parastatal or Public

Entities being calculated from the preceding ones.

While this data is obviously also not exhaustive, it provides the most reliable information

currently available on the extent of involvement of States, Parastatal and Public Entities in

arbitration in the European Union over the past 5 years.

Arbitration and Mediation Centre of Paris (CMAP)

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: approximately 90

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU): 0%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 0% (none)

Barcelona Arbitration Court

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 390

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU):

Less than 5%

5

______________________________________________________________

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): Less than 5% (less than approximately 20)

Centre for Effective Dispute Resolution (CEDR)

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 1,829

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU): 0%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 0% (none)

Court of Arbitration attached to the Hungarian Chamber of Commerce and Industry

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 1111

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU): 6%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 6% (approximately 67)

Court of Arbitration of Madrid

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 632

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party over past 5 years

(including non-EU): 4%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 4% (approximately 25)

Court of Arbitration of the Estonian Chamber of Commerce and Industry

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 85 since 2010

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU):

10%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 10% (approximately 9 since 2010) (estimate of

approximately 11 over past 5 years)

Court of Arbitration of the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 25-50

Investor-State arbitrations: No response

State-State arbitrations: No response

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU): 0%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 0% (none)

Danish Institute of Arbitration

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 647

Investor-State arbitrations: 0.3%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU):

7.7%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 7.4% (approximately 48)

6

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

Department of Arbitration, Athens Chamber of Commerce and Industry

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 25 completed

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party over past 5 years

(including non-EU): 10% (approximately 3 completed) (possibly including Investor-State

and State-State arbitrations)

DIS (German Institute of Arbitration)

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 743

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party over past 5 years

(including non-EU): 2% (approximately 15) (possibly including Investor-State and State-

State arbitrations)

ICC International Court of Arbitration

(Data from the ICC was provided independently, and not via questionnaire)

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 3,932

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party over past 5 years

(including non-EU): approximately 10.1% (approximately 399) (possibly including

Investor-State and State-State arbitrations)

International Centre for Dispute Resolution (ICDR)

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 4,879

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party over past 5 years

(including non-EU): 0.23% (approximately 11) (possibly including Investor-State and

State-State arbitrations)

Italian Association for Arbitration

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 23

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU):

10%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 10% (approximately 2)

London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA)

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 1,297

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party over past 5 years

(including non-EU): 5-10% (approximately 65-130) (possibly including Investor-State and

State-State arbitrations)

London Maritime Arbitrators Association

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 6,200

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU): 0%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 0% (none)

Netherlands Arbitration Institute

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 640

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU): 8%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 8% (approximately 51)

7

______________________________________________________________

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

Permanent Arbitration Court of the Slovak Banking Association

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 29,290

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU): 0%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 0% (none)

Spanish Court of Arbitration (CEA)

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 347

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU):

15%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 15% (approximately 52)

Venice Chamber of Arbitration

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 66

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU): 0%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 0% (none)

Vienna International Arbitral Centre

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 329

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU):

10% (over past 3 years)

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 10% (over past 3 years) (estimate of approximately

33 over past 5 years)

Vilnius Court of Commercial Arbitration

Arbitrations commenced over past 5 years: 151

Investor-State arbitrations: 0%

State-State arbitrations: 0%

Arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party (including non-EU):

2.6%

Commercial and other arbitrations involving a State, Parastatal or Public Entity as a party

over past 5 years (including non-EU): 2.6% (approximately 4)

8

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

1.2. Investment Arbitrations, State-State Arbitrations, and WTO

Arbitrations

1.2.1. Austria

Investment arbitration: (0)

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.2. Belgium

Investment arbitration (1)

Ping An Life Insurance Company of China, Limited and Ping An Insurance (Group) Company

of China, Limited v. Kingdom of Belgium (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/29)

WTO dispute settlement: (3)

United States v. Belgium, DS80 (in consultations on 2 May 1997)

United States v. Belgium, DS127 (in consultations on 5 May 1998)

United States v. Belgium, DS210

State-state arbitration: (4)

Arrest Warrant of 11 April 2000 (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium), ICJ

Jurisdiction and Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters (Belgium v.

Switzerland), ICJ

Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Belgium), ICJ

Questions relating to the Obligation to Prosecute or Extradite (Belgium v. Senegal), ICJ

1.2.3. Bulgaria

Investment arbitration: (7)

Accession Eastern Europe Capital AB and Mezzanine Management Sweden AB v. Republic of

Bulgaria (ICSID Case No. ARB/11/3)

EVN AG v. Republic of Bulgaria (ICSID Case No. ARB/13/17)

Novera AD, Novera Properties B.V. and Novera Properties N.V. v. Republic of Bulgaria

(ICSID Case No. ARB/12/16)

Plama Consortium Ltd. (Cyprus) v. Bulgaria (ICSID Case No. ARB/03/24)

ST-AD GmbH v. Republic of Bulgaria, UNCITRAL, PCA Case No. 2011-06

Zeevi Holdings v. Bulgaria and Privatization Agency of Bulgaria, Final award, UNCITRAL

Case No. UNC 39/DK, IIC 360 (2006), 25th October 2006, Ad hoc Tribunal (UNCITRAL)

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.4. Croatia

Investment arbitration: (5)

Adria Beteiligungs GmbH v. The Republic of Croatia, UNCITRAL

Georg Gavrilovic and Gavrilovic d.o.o. v. Republic of Croatia (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/39)

MOL Nyrt. (Hungary) v. Croatia (ICSID Case No. ARB/13/32)

Lieven J. van Riet, Chantal C. van Riet and Christopher van Riet v. Republic of Croatia

(ICSID Case No. ARB/13/12)

Ulemek v. Croatia, UNCITRAL

9

______________________________________________________________

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

WTO dispute settlement: (1)

Hungary v. Croatia, DS297

State-state arbitration (2)

Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

(Croatia v. Serbia), ICJ

Republic of Croatia v. the Republic of Slovenia, PCA

1.2.5. Cyprus

Investment arbitration (2)

Laiki Bank and the Bank of Cyprus v. Republic of Cyprus (in mandatory settlement

discussions prior to filing of claim at ICSID)

Marfin Investment Group Holdings S.A., Alexandros Bakatselos and others v.

Republic of Cyprus (ICSID Case No. ARB/13/27)

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.6. Czech Republic

Investment arbitration: (24)

Antaris Solar and Dr. Michael Göde v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL, PCA

Binder v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL

CME Czech Republic B.V. v. The Czech Republic, UNCITRAL

Diag Human S.E. v. The Czech Republic, ad hoc

Eastern Sugar B.V.(Netherlands) v. The Czech Republic, SCC Case No. 088/2004

ECE Projektmanagement v. The Czech Republic, UNCITRAL

European Media Ventures SA v. The Czech Republic, UNCITRAL

Frontier Petroleum Services Ltd. v. The Czech Republic, UNCITRAL

InterTrade Holding GmbH v. The Czech Republic, UNCITRAL, PCA

ICW Europe Investments Limited v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL ad hoc

Invesmart v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL

Konsortium Oeconomismus v. Czech Republic

Ronald S. Lauder v. The Czech Republic, UNCITRAL

William Nagel v. The Czech Republic, SCC Case No. 049/2002

Georg Nepolsky v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL

Natland Investment Group NV, Natland Group Limited, G.I.H.G. Limited, and Radiance

Energy Holding S.A.R.L. v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL ad hoc

Phoenix Action Ltd v. Czech Republic (ICSID Case No. ARB/06/5)

Photovoltaik Knopf Betriebs-GmbH v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL ad hoc

Pren Nreka v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL

Saluka Investments B.V. v. The Czech Republic, UNCITRAL

Peter Franz Vocklinghaus v. Czech Republic

Voltaic Network GmbH v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL ad hoc

WA Investments-Europa Nova Limited v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL ad hoc

Mr. Jürgen Wirtgen, Mr. Stefan Wirtgen, and JSW Solar (zwei) v. Czech Republic, UNCITRAL

ad hoc

10

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

WTO dispute settlement: (2)

Czech Republic v. Hungary, DS159

Hungary v. Czech Republic, DS148

Poland v. Czech Republic, DS289

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.7. Denmark

Investment arbitration: (0)

WTO dispute settlement: (2)

Denmark v. European Union, DS469

Complaint by Denmark in respect of the Faroe Islands

United States v. Denmark, DS83

State-State arbitration (1)

1

The Atlanto-Scandian Herring Arbitration (The Kingdom of Denmark in respect of the Faroe

Islands v. The European Union), PCA Case No, 2013-30

1.2.8. Estonia

Investment arbitration: (4)

AS Tallinna Vesi v. Estonia, ICSID (filed May 13, 2014)

Alex Genin and others v. Republic of Estonia (ICSID Case No. ARB/99/2)

OKO Pankki Oyj and others v. Republic of Estonia (ICSID Case No. ARB/04/6)

Rail World Estonia LLC and others v. Republic of Estonia (ICSID Case No. ARB/06/6)

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.9. Finland

Investment arbitration: (0)

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.10. France

Investment arbitration: (2)

The Channel Tunnel Group Limited and France-Manche S.A., and the Governments of the

United Kingdom and France (Eurotunnel Arbitration), PCA

Erbil Serter v. French Republic (ICSID Case No. ARB/13/22)

WTO dispute settlement: (4)

United States v. European Communities, France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom, DS316

United States v. European Communities, France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom, DS347

United States v. France, DS131

United States v. France, DS173 (this complaint is identical to the one addressed to the EC

(WT/DS172)

1

This is not strictly a State-State arbitration, as one pary is the European Union. Beyond this technicality,

however, it is most accurately classified in this section.

11

______________________________________________________________

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

State-state arbitration: (7)

The "Camouco" Case (Panama v. France), Prompt Release, ITLOS, Case No. 5

Certain Criminal Proceedings in France (Republic of the Congo v. France), ICJ

Certain Questions of Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters (Djibouti v. France), ICJ

The "Grand Prince" Case (Belize v. France), Prompt Release, ITLOS, Case No. 8

Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. France), ICJ

The "Monte Confurco" Case (Seychelles v. France), Prompt Release, ITLOS, Case No. 6

The Kingdom of Netherlands – Republic of France 1976 Convention on Protection of the

Rhine Against Pollution by Chlorides, PCA

1.2.11. Germany

Investment arbitration: (3)

A case was initiated in 2000 by an Indian investor under the Germany-India BIT pursuant

to UNCITRAL Rules (information on this case is not publicly available)

Vattenfall AB, Vattenfall Europe AG, Vattenfall Europe Generation AG & Co. KG (Sweden) v.

Federal Republic of Germany (ICSID Case No. ARB/09/6)

Vattenfall AB (Sweden) et al v. Germany (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/12)

WTO dispute settlement: (2)

United States v. European Communities, France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom, DS316

United States v. European Communities, France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom, DS347

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.12. Greece

Investment arbitration: (1)

2

Poštová banka, a.s. and ISTROKAPITAL SE v. Hellenic Republic (ICSID Case No. ARB/13/8)

WTO dispute settlement: (3)

United States v. Greece, DS125

United States v. Greece, DS129

China v. European Union, Italy, Greece, DS452

State-state arbitration: (4)

Certain Property (Liechtenstein v. Germany), ICJ

Jurisdictional Immunities of the State (Germany v. Italy: Greece intervening) ICJ

LaGrand (Germany v. United States of America), ICJ

Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Monténégro v. Germany), ICJ

1.2.13. Hungary

Investment arbitration: (12)

Accession Mezzanine Capital L.P. and Danubius Kereskedöház Vagyonkezelö Zrt. v.

Hungary (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/3)

ADC Affiliate Limited and ADC & ADMC Management Limited v. Republic of Hungary (ICSID

Case No. ARB/03/16)

AES Summit Generation Ltd. (UK subsidiary of US-based AES Corporation) v. Hungary

ICSID Case No. ARB/01/4

2

Although Greece is known to have been involved in other investment-related arbitrations, accurate statistics are

unavailable due to confidentiality restrictions.

12

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

AES Summit Generation Limited and AES-Tisza Erömü Kft. (UK) v. Republic of Hungary

(ICSID Case No. ARB/07/22)

Le Chèque Déjeuner and C.D Holding Internationale v. Hungary (ICSID Case No.

ARB/13/35)

Dan Cake (Portugal) S.A. v. Hungary (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/9)

Edenred S.A. v. Hungary (ICSID Case No. ARB/13/21)

EDF International S.A. (France) v. Republic of Hungary, UNCITRAL ad hoc

Electrabel S.A. (Belgium) v. Republic of Hungary (ICSID Case No. ARB/07/19)

Emmis International Holding, B.V., Emmis Radio Operating, B.V., and MEM Magyar

Electronic Media Kereskedelmi és Szolgáltató Kft. v. Hungary (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/2)

Telenor Mobile Communications AS v. Republic of Hungary (ICSID Case No. ARB/04/15)

Vigotop Limited v. Hungary (ISCID Case No. ARB/11/22)

WTO dispute settlement: (7)

Czech Republic v. Hungary, DS159

Hungary v. Czech Republic, DS148

Hungary v. Romania, DS240

Hungary v. Slovak Republic, DS143

Hungary v. Turkey, DS256

Hungary v. Croatia, DS297

United-States v. Japan, DS76 (Acting as a third-country, together with the EC and Brazil)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.14. Ireland

Investment arbitration: (0)

WTO dispute settlement: (2)

United States v. Ireland, DS82

United States v. Ireland, DS130

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.15. Italy

Investment arbitration: (1)

Blusun SA, Jean-Pierre Lecorcier and Michael Stein v. Italian Republic (ICSID Case No.

ABR/14/3)

WTO dispute settlement: (1)

China v. European Union, Italy, Greece, DS452

State-state arbitration: (2)

Italian Republic v. Republic of Cuba, ad hoc state-state arbitration

Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Italy), ICJ

1.2.16. Latvia

Investment arbitration: (3)

Nykomb Synergetics Technology Holding AB (Sweden) v. The Republic of Latvia, SCC -

Case No 118/2001

Swembalt AB, Sweden v. The Republic of Latvia, UNCITRAL

UAB E energija (Lithuania) v. Republic of Latvia (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/33)

13

______________________________________________________________

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.17. Lithuania

Investment arbitration: (5)

Vladimir Antonov v. Republic of Lithuania, ICC

Luigiterzo Bosca v. Lithuania, UNCITRAL

Kaliningrad Region v. Lithuania, ICC

OAO Gazprom v. The Republic of Lithuania, UNCITRAL, PCA

Parkerings-Compagniet AS v. Republic of Lithuania (ICSID Case No. ARB/05/8)

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.18. Luxembourg

Investment arbitration: (0)

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.19. Malta

Investment arbitration: (0)

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.20. Netherlands

Investment arbitration: (0)

WTO dispute settlement: (3)

Brazil v. European Union, Netherlands, DS409

India v. European Union, Netherlands, DS408

United States v. Netherlands, DS128

State-state arbitration: (4)

Arctic Sunrise Arbitration (Netherlands v. Russia), PCA

Belgium v. The Netherlands, Arbitration regarding the Iron Rhine Railway, PCA

Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Netherlands), ICJ

The Kingdom of Netherlands – Republic of France 1976 Convention on Protection of the

Rhine Against Pollution by Chlorides, PCA

1.2.21. Poland

Investment arbitration: (14)

Cargill v. Poland, UNCITRAL

Cargill, Incorporated v. Republic of Poland (ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/04/2)

Crespo and others v. Poland, ICC

East Cement for Investment Company v. Poland, ICC

Eureko B.V. v. Republic of Poland

14

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

Les Laboratoires Servier, S.A.A., Biofarma, S.A.S., Arts et Techniques du Progres S.A.S. v.

Republic of Poland, UNCITRAL

Mercuria Energy Group Ltd. (Cyprus) v. Republic of Poland, SCC

David Minotte and Robert Lewis v Republic of Poland (ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/10/1)

Nordzucker v. Poland, UNCITRAL

Saar Papier Vertriebs GmbH v. Poland, UNCITRAL

Techniques du Progres S.A.S. v. Republic of Poland, UNCITRAL

TRACO Deutsche Travertinwerke GmbH v. The Republic of Poland, UNCITRAL

Vincent J. Ryan, Schooner Capital LLC, and Atlantic Investment Partners LLC v. Republic of

Poland (ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/11/3)

Vivendi v. Republic of Poland, UNCITRAL

WTO dispute settlement: (4)

European Communities v. Canada (Acting as a third-party together with Australia, Brazil,

Colombia, Cuba, India, Israel, Japan, Switzerland, Thailand, United States), DS114

Poland v. Thailand (European Communities, Japan, United States as third-parties), DS122

Poland v. Slovak Republic, DS235

Poland v. Czech Republic, DS289

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.22. Portugal

Investment arbitration: (0)

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (1)

Legality of Use of Force (Serbia and Montenegro v. Portugal), ICJ

1.2.23. Romania

Investment arbitration: (9)

Hassan Awdi, Enterprise Business Consultants, Inc. and Alfa El Corporation v. Romania

(ICSID Case No. ARB/10/13)

Ömer Dede and Serdar Elhüseyni v. Romania (ICSID Case No. ARB/10/22)

EDF (Services) Limited v. Romania (ICSID Case No. ARB/05/13)

Marco Gavazzi and Stefano Gavazzi v. Romania (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/25)

Ioan Micula, Viorel Micula, S.C. European Food S.A, S.C. Starmill S.R.L. and S.C. Multipack

S.R.L. v. Romania (ICSID Case No. ARB/05/20)

Noble Ventures, Inc. v. Romania (ICSID Case No. ARB/01/11)

The Rompetrol Group N.V. v. Romania (ICSID Case No. ARB/06/3)

S&T Oil Equipment & Machinery Ltd. v. Romania (ICSID Case No. ARB/07/13)

Spyridon Roussalis v. Romania (ICSID Case No. ARB/06/1)

WTO dispute settlement: (2)

Hungary v. Romania, DS240

United States v. Romania, DS198

State-state arbitration: (1)

Maritime Delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania v. Ukraine), ICJ

15

______________________________________________________________

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

1.2.24. Slovak Republic

Investment arbitration: (13)

Achmea B.V. v. The Slovak Republic, UNCITRAL, PCA Case No. 2008-13 (formerly Eureko

B.V. v. The Slovak Republic)

Alps Finance and Trade AG v. The Slovak Republic, UNCITRAL

Austrian Airlines v. The Slovak Republic, UNCITRAL

Československa obchodní banka, a.s. v. Slovak Republic (ICSID Case No. ARB/97/4)

EuroGas GmbH v. Slovak Republic, UNCITRAL

European American Investment Bank AG v. The Slovak Republic, UNCITRAL, PCA

HICEE B.V. v. The Slovak Republic, UNCITRAL, PCA Case No. 2009-11

Branimir Mensik v. Slovak Republic (ICSID Case No. ARB/06/9)

Jan Oostergetel and Theodora Laurentius v. The Slovak Republic, UNCITRAL

Slovak Gas Holding BV, GDF International SAS and E.ON Ruhrgas International GmbH v.

Slovak Republic (ICSID Case No. ARB/12/7)

U.S. Steel Global Holdings I B.V. (The Netherlands) v. The Slovak Republic, UNCITRAL, PCA

WTO dispute settlement: (3)

Hungary v. Slovak Republic, DS143

Poland v. Slovak Republic, DS235

Switzerland v. Slovak Republic, DS133

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.25. Slovenia

Investment arbitration: (3)

Hrvatska Elektroprivreda d.d. (HEP) (Croatia) v. Republic of Slovenia (ICSID Case No.

ARB/05/24)

Impresa Grassetto S. p. A., in liquidation v. Republic of Slovenia (ICSID Case No.

ARB/13/10)

Interbrew Central European Holding B.V. v. Republic of Slovenia (ICSID Case No.

ARB/04/17)

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.26. Spain

Investment arbitration: (10)

Antin Infrastructure Services Luxembourg S.à.r.l. and Antin Energia Termosolar B.V. v.

Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/13/31)

Charanne (the Netherlands) and Construction Investments (Luxembourg) v. Spain, SCC

CSP Equity Investment S.à.r.l. v. Spain, SCC

Eiser Infrastructure Limited and Energia Solar Luxembourg S.a.r.l. v. Spain (ICSID Case

No. ARB/13/36)

Inversión y Gestión de Bienes, IGB, S.L. and IGB18 Las Rozas, S.L. v. Kingdom of Spain

(ICSID Case No. ARB/12/17)

Isolux Infrastructure Netherlands B.V. v. Spain, SCC

Emilio Agustín Maffezini v. Kingdom of Spain (ICSID Case No. ARB/97/7)

Masdar Solar & Wind Cooperatief UA v. Spain (ICSID Case No. ABR/14/01)

The PV Investors v. Spain, Ad hoc UNCITRAL Arbitration

16

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

RREEF Infrastructure (G.P.) Limited and RREEF Pan-European RREEF Infrastructure (G.P.)

Limited and RREEF Pan-European Infrastructure Two Lux S.à r.l. v. Kingdom of Spain

(ICSID Case No. ARB/13/30)

WTO dispute settlement: (3)

Argentina v. European Union, Spain, DS443

United States v. European Communities, France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom (third-

parties: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Japan, Republic of Korea), DS316

United States v. European Communities, France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom (third-

parties: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Japan, Republic of Korea), DS347

State-state arbitration: (2)

Legality of Use of Force (Yugoslavia v. Spain), ICJ

The M/V "Louisa" Case (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines v. Kingdom of Spain), ITLOS,

Case No. 18

1.2.27. Sweden

Investment arbitration: (0)

WTO dispute settlement: (0)

State-state arbitration: (0)

1.2.28. United Kingdom

Investment arbitrations: (1)

Ashok Sancheti v. United Kingdom, UNCITRAL

WTO dispute settlement: (2)

United States v. European Communities, France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom, DS316

United States v. European Communities, France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom, DS347

State-state arbitration: (5)

The Channel Tunnel Group Limited and France-Manche S.A., and the Governments of the

United Kingdom and France (Eurotunnel Arbitration), PCA

Ireland v. United Kingdom ("MOX Plant Case")

Ireland v. United Kingdom, proceedings pursuant to the OSPAR Convention

The Republic of Mauritius v. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

Obligations concerning Negotiations relating to Cessation of the Nuclear Arms Race and to

Nuclear Disarmament (Marshall Islands v. United Kingdom), ICJ

1.2.29. Switzerland

Investment arbitration: (0)

WTO dispute settlement:

Switzerland v. Slovak Republic, DS133

Switzerland v. United States (third parties: Brazil, Canada, China, Chinese Taipei, Cuba,

European Communities, Japan, Republic of Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Thailand,

Turkey, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela), DS253

Acting as third country:

China v. United States (third parties: Brazil, Canada, Chinese Taipei, Cuba, European

Communities, Japan, Republic of Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland,

Thailand, Turkey, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela), DS252

17

______________________________________________________________

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

European Communities v. Canada (third parties: Australia, Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, India,

Israel, Japan, Poland, Switzerland, Thailand United States), DS114

European Communities v. United States (third parties: Australia, Brazil, Canada, Japan,

Switzerland), DS160

European Communities v. United States (third parties: Brazil, Canada, China, Chinese

Taipei, Cuba, Japan, Republic of Korea, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Thailand,

Turkey, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela), DS248

Japan v. Argentina (third parties: Australia, Canada, China, Ecuador, European Union,

Guatemala, India, Israel, Japan, Republic of Korea, Norway, Saudi Arabia, Kingdom of

Switzerland, Chinese Taipei, Thailand, Turkey, United States), DS445

Japan v. United States (third-parties: Brazil, Canada, China, Chinese Taipei, European

Communities, Republic of Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Thailand,

Turkey, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela), DS249

European Union v. Argentina (third parties: Australia; Canada; China; Ecuador; European

Union; Guatemala; India; Israel; Japan; Korea, Republic of; Norway; Saudi Arabia,

Kingdom of; Switzerland; Chinese Taipei; Thailand; Turkey; United States), DS438

Republic of Korea v. United States (third parties: Brazil, Canada, China, Chinese Taipei,

European Communities, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Thailand,

Turkey, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela), DS251

New Zealand v. United States, (third parties: Brazil; Canada; China; Chinese Taipei; Cuba;

European Communities; Japan; Korea, Republic of; Mexico; Norway; Switzerland; Thailand;

Turkey; Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of), DS258

Norway v. United States (third parties: Brazil; Canada; China; Chinese Taipei; Cuba;

European Communities; Japan; Korea, Republic of; Mexico; New Zealand; Switzerland;

Thailand; Turkey; Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of), DS254

United States v. Argentina (third countries: Australia; Canada; China; Ecuador; European

Union; Guatemala; India; Israel; Japan; Korea, Republic of; Norway; Saudi Arabia,

Kingdom of; Switzerland; Chinese Taipei; Thailand; Turkey; United States), DS444

State-state arbitration: (2)

Jurisdiction and Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters (Belgium v.

Switzerland), ICJ

Status vis-à-vis the Host State of a Diplomatic Envoy to the United Nations

(Commonwealth of Dominica v. Switzerland), ICJ

1.2.30. European Union (formerly European Communities)

WTO dispute settlement:

WTO arbitration under Article 25 of the DSU:

ECP-EC Partnership Arbitration – “Banana Tariffs,” WT/L/616

Second ECP-EC Partnership Arbitration – “Banana Tariffs,” WT/L/625

WTO arbitration under Article 21 of the DSU:

EU (EC) acting as third party to original WTO proceedings:

WT/DS414/12 (China – United States)

WT/DS384/24, WT/DS386/23 (Canada – United States)

WT/DS366/13 (Panama - Colombia)

WT/DS344/15 (Mexico – United States)

WT/DS336/16 (Republic of Korea – Japan)

WT/DS322/21 (Japan – United States)

WT/DS302/17 (Honduras – Dominican Republic)

18

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

WT/DS285/13 (Antigua and Barbuda – United States)

WT/DS268/12 (Argentina – United States)

WT/DS264/13 (Canada – United States)

WT/DS207/13 (Argentina – Chile)

WT/DS202/17 (Republic of Korea – United States)

WT/DS184/13 (Japan – United States)

EU (EC) acting as Respondent to original WTO proceedings:

WT/DS246/14 (India – EC)

WT/DS265/33, WT/DS266/33, WT/DS283/14 (Australia – EC)

WT/DS269/13, WT/DS286/15 (Brazil – EC)

EU (EC) acting as Complainant to original WTO proceedings:

WT/DS332/16 (EC – Brazil)

WT/DS75/16, WT/DS84/14 (EC – Republic of Korea)

WT/DS87/15, WT/DS110/14 (EC – Chile)

WT/DS114/13 (EC – Canada)

WT/DS160/12 (EC – United States)

WT/DS136/11, WT/DS162/14 (EC – United States)

WT/DS155/10 (EC – Argentina)

WT/DS217/14, WT/DS234/22 (Australia; Brazil; Chile; European Communities; India;

Indonesia; Japan; Korea, Republic of; Thailand – United States)

WTO Complaints launched by the EU:

Argentina, WT/DS121 - Safeguard measures on footwear

Argentina, WT/DS155 - Measures on the export of bovine hides and the import of finished

leather

Argentina, WT/DS157, Definitive Anti-Dumping Measures on Imports of Drill Bits from Italy

Argentina, WT/DS189 - Definitive anti-dumping measures on imports of ceramic floor tiles

from Italy

Argentina, WT/DS330 – Countervailing Duties on Olive Oil, Wheat Gluten and Peaches

Argentina, WT/DS438 – Measures Affecting the Importation of Goods

Australia, WT/DS287 - Quarantine Regime for Imports

Brazil, WT/DS 472 - Brazil Taxation

Brazil, WT/DS Measures on Import Licensing and Minimum Import Prices

Brazil, WT/DS332 - Measures affecting imports of retreaded tyres

Canada, WT/DS114 - Patent protection of pharmaceutical product

Canada, WT/DS142 - Certain measures affecting the automotive industry

Canada, WT/DS321 - Continued Suspension of Obligations in the EC-Hormones Dispute

Canada, WT/DS354 - Tax exemptions and reductions for wine and beer

Canada, WT/DS426 - Measures Relating to the Feed-in Tariff Program

Chile, WT/DS193 - Measures affecting the transit and importation of swordfish

Chile, WT/DS87 - Taxes on alcoholic beverages

China, WT/DS 372 - China – Measures Affecting Financial Information Services and Foreign

Financial Information Suppliers

China, WT/DS 460 - China – Measures Imposing Anti-Dumping Duties on High-Performance

Stainless Steel Seamless Tubes ("HP-SSST") from the European Union

China, WT/DS339 - Measures affecting imports of automobile parts

China, WT/DS395 - China — Measures Related to the Exportation of Various Raw Materials

China, WT/DS407 - Provisional Anti-Dumping Duties on Certain Iron and Steel Fasteners

from the European Union

China, WT/DS425 - Definitive anti-dumping duties on x-ray security inspection equipment

from the EU - China

19

______________________________________________________________

2007

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

China, WT/DS432 - China - Measures Related to the Exportation of Rare Earths, Tungsten

and Molybdenum

India, WT/DS146 - Measures affecting the automotive sector

India, WT/DS149 - Import restrictions

India, WT/DS150 - Measures affecting customs duties

India, WT/DS279 - Import restrictions maintained under the export and import policy 2002-

India, WT/DS304 - Anti-dumping measures on imports of certain products from the EC

and/or Member States

India, WT/DS352 - India - Measures Affecting the Importation and Sale of Wines and

Spirits from the European Communities

India, WT/DS380, Certain Taxes and Other Measures on Imported Wines and Spirits

Indonesia, WT/DS481, Recourse to article 22.2 of the DSU in the US — Clove cigarettes

dispute

Korea, Republic Of, WT/DS273 - Measures affecting trade in commercial vessels -

Korea, Republic Of, WT/DS75 - Taxes on alcoholic beverages -

Korea, Republic Of, WT/DS98 - Definitive safeguard measures on imports of certain dairy

products -

Mexico, WT/DS314 - Provisional Countervailing Measures on Olive Oil from the European

Communities

Mexico, WT/DS341 - Mexico - Definitive countervailing measures measures on olive oil from

the European Communities

Philippines, WT/DS396 - Philippines - taxes on distilled spirits

Russian Federation, WT/DS462 - Russian Federation- Recycling fee on motor vehicles

Russian Federation, WT/DS475, Measures on the Importation of Live Pigs, Pork and Other

Pig Products from the European Union

Russian Federation, WT/DS479, Anti-Dumping Duties on Light Commercial Vehicles from

Germany and Italy

Thailand, WT/DS370 - Thailand - Customs valuation of certain products from the EC

United States, WT/DS108 - Tax treatment for "Foreign Sales Corporations"

United States, WT/DS136 - Anti-dumping Act of 1916

United States, WT/DS138 - Imposition of countervailing duties on certain hot-rolled lead

and bismuth carbon steel products originating in the UK

United States, WT/DS152 - Sections 301-310 of the Trade Act of 1974

United States, WT/DS160 - Section 110(5) of US Copyright Act

United States, WT/DS160, Section 110(5) of US Copyright Act

United States, WT/DS165 - Import measures on certain products from the EC

United States, WT/DS165, Import Measures on Certain Products from the European

Communities

United States, WT/DS166 - Definitive safeguard measures on imports of wheat gluten from

EC

United States, WT/DS166, Definitive Safeguard Measures on Imports of Wheat Gluten from

the European Communities

United States, WT/DS176 - Section 211 Omnibus Appropriations Act

United States, WT/DS176, Section 211 Omnibus Appropriations Act of 1998

United States, WT/DS186 - Section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930 and amendments thereto

United States, WT/DS200 - Section 306 of the Trade Act of 1974 and amendments thereto

("carousel")

United States, WT/DS212 - Countervailing measures concerning certain products from the

EC

United States, WT/DS213 - Countervailing duties on certain corrosion-resistant carbon steel

flat products from Germany

20

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

United States, WT/DS214, Definitive Safeguard Measures on Imports of Steel Wire Rod and

Circular Welded Quality Line Pipe

United States, WT/DS217 - Continued dumping and subsidy offset Act of 2000

United States, WT/DS225, Anti-Dumping Duties on Seamless Pipe from Italy

United States, WT/DS248 - Definitive safeguard measures on imports of certain steel

products

United States, WT/DS262 - Sunset Reviews of Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duties on

Certain Steel Products from France and Germany

United States, WT/DS294 - Laws, regulations and methodology for calculating dumping

margins ('zeroing')

United States, WT/DS317 - Measures Affecting Trade in Large Civil Aircraft

United States, WT/DS319 - Section 776 of the Tariff Act of 1930

United States, WT/DS320 - Continued Suspension of Obligations in the EC-Hormones

Dispute

United States, WT/DS350 - Continued Existence and Application of zeroing methodology

United States, WT/DS353 - Measures Affecting Trade in Large Civil Aircraft (second

complaint)

United States, WT/DS424 - United States – Anti-Dumping Measures on Imports of Stainless

Steel Sheet and Strip in Coils from Italy

WTO Complaints against the EU:

Argentina, WT/DS349 - EC - Measures affecting the tariff quota for fresh or chilled garlic

Argentina, WT/DS443 - European Union and a Member State — Certain Measures

Concerning the Importation of Biodiesels

Argentina, WT/DS293 - Measures affecting the approval and marketing of biotech products

(GMOs)

Argentina, WT/DS263 - Measures affecting imports of wine

Australia, WT/DS290 - Protection of trademarks and geographical indications for

agricultural products and foodstuffs

Australia, WT/DS265 - Export subsidies on sugar

Brazil, WT/DS219 - Anti-dumping duties on malleable cast iron tube or pipe fittings from

Brazil

Brazil, WT/DS269 - Customs classification of frozen boneless chicken cuts

Brazil, WT/DS266 - Export subsidies on sugar

Brazil, WT/DS409 - European Union and a Member State - Seizure of Generic Drugs in

Transit

Canada, WT/DS135 - Measures affecting the prohibition of asbestos and asbestos products

Canada, WT/DS400 - European Communities - Measures Prohibiting the Importation and

Marketing of Seal Products

Canada, WT/DS 369 - EC - Certain Measures Prohibiting the Importation and Marketing of

Seal Products

Canada, WT/DS48 - Measures affecting livestock and meat (Hormones)

Canada, WT/DS292 - Measures affecting the approval and marketing of biotech products

(GMOs)

China, WT/DS452 - European Union and certain Member States — Certain Measures

Affecting the Renewable Energy Generation Sector

China, WT/DS397 - European Communities - Definitive Anti-Dumping Measures on certain

iron or steel fasteners from China

China, WT/DS405 - European Union - Anti-Dumping Measures on Certain Footwear from

China

Colombia, WT/DS 361 - EC - Regime For the Importation of Bananas

Ecuador, WT/DS27 - Import regime for bananas

21

______________________________________________________________

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

Guatemala, WT/DS27 - Import regime for bananas

Honduras, WT/DS27 - Import regime for bananas

India, WT/DS246 - Conditions for the granting of tariff preferences to developing countries

India, WT/DS313 - Anti-dumping duties on certain flat rolled iron or non-alloy steel

products

India, WT/DS141 - Anti-dumping duties on imports of cotton-type bed-linen from India

India, WT/DS408 - European Union and a Member State - Seizure of Generic Drugs in

Transit

Japan, WT/DS376 - Tariff Treatment of Certain Information Technology Products

Korea, Republic Of, WT/DS307 - Aid for commercial vessels

Korea, Republic Of, WT/DS301 - Measures affecting trade in commercial vessels

Korea, Republic Of, WT/DS299 - Countervailing measures on dynamic random access

memory chips (DRAMS)

Mexico, WT/DS27 - Import regime for bananas

Norway, WT/DS401 - European Communities — Measures Prohibiting the Importation and

Marketing of Seal Products

Norway, WT/DS328 - Definitive Safeguard Measure on Salmon

Norway, WT/DS 337 - Anti-Dumping Measure on Farmed Salmon from Norway

Panama, WT/DS364 - EC - Regime for the Importation of Bananas

Peru, WT/DS231 - Trade description of sardines

Taiwan (Chinese Taipei), WT/DS377 - Tariff Treatment of Certain Information Technology

Products

Thailand, WT/DS286 - Customs classification of frozen boneless chicken cuts

Thailand, WT/DS242 - Certain measures under the EC's scheme of generalized system of

preference (GSP)

Thailand, WT/DS283 - Export subsidies on sugar

United States, WT/DS375 - Tariff Treatment of Certain Information Technology Products

United States, WT/DS315 - European Communities - Selected Customs Matters

United States, WT/DS223 - Tariff-rate quota on corn gluten feed from the United States

United States, WT/DS27 - Import regime for bananas

United States, WT/DS316 - Measures Affecting Trade in Large Civil Aircraft

United States, WT/DS260 - Provisional safeguards measures on imports of certain steel

products

United States, WT/DS174 - Protection of trademarks and geographical indications for

agricultural products and foodstuffs

United States, WT/DS26 - Measures affecting meat and meat products (Hormones)

United States, WT/DS291 - Measures affecting the approval and marketing of biotech

products (GMOs)

EU as third party to WTO complaints:

Antigua And Barbuda, WT/DS285 - Measures affecting the cross-border supply of gambling

and betting services

Argentina, WT/DS207 - Price band system and safeguard measures relating to certain

agricultural products

Argentina, WT/DS268 - Sunset review of AD measures on oil country tubular goods

Bangladesh, WT/DS306 - Anti-dumping measure on batteries from Bangladesh

Brazil, WT/DS382 - US - Anti-Dumping Administrative Reviews and Other Measures Related

to Imports of Certain Orange Juice from Brazil

Brazil, WT/DS241 - Anti-dumping duties on poultry from Brazil

Brazil, WT/DS267 - Subsidies on upland cotton

Brazil, WT/DS250 - Equalizing excise tax imposed by Florida on processed orange and

grapefruit products

22

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

Brazil, WT/DS239 - Anti-dumping duties on silicon metal from Brazil

Canada, WT/DS257 - Final countervailing duty determination with respect to certain

softwood lumber

Canada, WT/DS277 - Investigation of the international trade commission in softwood

lumber

Canada, WT/DS391 - Korea — Measures Affecting the Importation of Bovine Meat and Meat

Products from Canada

Canada, WT/DS264 - Anti-dumping - Final dumping determination on softwood lumber

Canada, WT/DS236 - Determination of countervailing duties on certain softwood lumber

Chile, WT/DS238 - Definitive safeguard measures on imports of preserved peaches

Chile, WT/DS232 - Measures affecting the import of matches

Chile, WT/DS261 - Tax treatment on certain products

China, WT/DS379 - United States - Definitive Anti - Dumping and Countervailing duties on

certain products from China

China, WT/DS399 - United States — Measures Affecting Imports of Certain Passenger

Vehicle and Light Truck Tyres from China

China, WT/DS422 - United States — Anti-Dumping Measures on Shrimp and Diamond

Sawblades from China

China, WT/DS437 - United States — Countervailing Duty Measures on Certain Products

from China

China, WT/DS449 - United States — Countervailing and Anti-dumping Measures on Certain

Products from China

Colombia, WT/DS188 - Measures affecting imports from Honduras and Colombia

Costa Rica, WT/DS415 - Dominican Republic — Safeguard Measures on Imports of

Polypropylene Bags and Tubular Fabric

El Salvador, WT/DS418 - Dominican Republic — Safeguard Measures on Imports of

Polypropylene Bags and Tubular Fabric

Guatemala, WT/DS416 - Dominican Republic — Safeguard Measures on Imports of

Polypropylene Bags and Tubular Fabric

Guatemala, WT/DS331 - Mexico ¿ Anti-Dumping Duties on Steel Pipes and Tubes from

Guatemala

Honduras, WT/DS417 - Dominican Republic — Safeguard Measures on Imports of

Polypropylene Bags and Tubular Fabric

Honduras, WT/DS201 - Measures affecting imports from Honduras and Colombia (II)

Honduras, WT/DS302 - Measures affecting the importation and internal sale of cigarettes

India, WT/DS243 - Rules of origin for textiles and apparel products

India, WT/DS206 - Anti-dumping and countervailing measures on steel plate from India

India, WT/DS345 - United States — Customs Bond Directive for Merchandise Subject to

Anti-Dumping/Countervailing Duties

India, WT/DS436 - United States — Countervailing Measures on Certain Hot-Rolled Carbon

Steel Flat Products from India

Indonesia, WT/DS312 - Korea — Anti-Dumping Duties on Imports of Certain Paper from

Indonesia

Indonesia, WT/DS406 - United States — Measures Affecting the Production and Sale of

Clove Cigarettes

Japan, WT/DS322 - Measures Relating to Zeroing and Sunset Reviews

Japan, WT/DS162 - Anti-dumping Act of 1916

Japan, WT/DS184 - Anti-dumping measures on certain hot-rolled steel products from Japan

Japan, WT/DS412 - Canada - Certain Measures Affecting the Renewable Energy Generation

Sector

Japan, WT/DS433 - China - Measures Related to the Exportation of rare Earths, Tungsten

and Molybdenum

23

______________________________________________________________

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

Japan, WT/DS244 - Sunset review of AD duties on corrosion-resistant carbon steel flat

products

Korea, Republic Of, WT/DS420 - United States — Anti-dumping measures on corrosion-

resistant carbon steel flat products from Korea

Korea, Republic Of, WT/DS336 - CV duty on DRAMS from Korea

Korea, Republic Of, WT/DS296 - CV duty investigation on DRAMS

Korea, Republic Of, WT/DS323 – Japan – Import quotas on dried laver and seasoned laver

JAPAN

Korea, Republic Of, WT/DS402 - US - Use of Zeroing in Anti-Dumping Measures Involving

Products from Korea

Mexico, WT/DS344 - US - Final Anti-Dumping Measures on Stainless Steel from Mexico

Mexico, WT/DS282 - Anti-dumping measures on oil country tubular goods

Mexico, WT/DS281 - Anti-dumping measures on cement

Mexico, WT/DS398 - China — Measures Related to the Exportation of Various Raw Materials

Moldova, Republic Of, WT/DS423 - Ukraine — Taxes on Distilled spirits

New Zealand, WT/DS367 - Australia — Measures Affecting the Importation of Apples from

New Zealand

Panama, WT/DS366 - Colombia - Indicative prices and restrictions on ports of entry

Philippines, WT/DS270 - Certain measures affecting the importation of fresh fruit and

vegetables

Philippines, WT/DS271 - Certain measures affecting the importation of fresh pineapple

Thailand, WT/DS383 - US - Anti-Dumping Measures on Polyethylene Retail Carrier Bags

from Thailand

Thailand, WT/DS343 - United States - Measures Relating to Shrimp from Thailand

Turkey, WT/DS211 - Definitive anti-dumping measures on steel rebar from Turkey

Ukraine, WT/DS434 - Australia - Certain Measures Concerning Trademarks and Other Plain

Packaging Requirements Applicable to tobacco Products and Packaging

Ukraine, WT/DS421 - Moldova — Measures Affecting the Importation and Internal Sale of

Goods (Environmental Charge)

United States, WT/DS295 - Definitive AD measures on beef and rice

United States, WT/DS309 - Value-added tax on integrated circuits

United States, WT/DS403 - Philippines — Taxes on Distilled Spirits

United States, WT/DS431 - China - Measures Related to the Exportation of rare Earths,

Tungsten and Molybdenum

United States, WT/DS427 - China — Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duty Measures on

Broiler Products from the United States

United States, WT/DS430 - India — Measures Concerning the Importation of Certain

Agricultural Products from the United States

United States, WT/DS440 - China — Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duties on Certain

Automobiles from the United States

United States, WT/DS276 - Measures relating to exports of wheat and treatment of

imported grain -

United States, WT/DS308 - Tax measures on soft drinks and other beverages

United States, WT/DS305 - Measures affecting imports of textile and apparel products

United States, WT/DS275 - Import licensing measures on certain agricultural products

United States, WT/DS204 - Measures affecting telecommunication services

United States, WT/DS245 - Measures affecting the importation of apples

United States, WT/DS175 - Measures affecting trade and investment in the motor vehicle

sector

United States, WT/DS360 - India - Additional and Extra-Additional duties India - Additional

and Extra-Additional duties on imports from the United States

24

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

United States, WT/DS363 - Measures affecting trading rights and distribution services for

certain publications and audiovisual entertainment products

United States, WT/DS362 - Measures affecting the protection and enforcement of

intellectual property rights

United States, WT/DS413 - China — Certain Measures Affecting Electronic Payment

Services

United States, WT/DS414 - China — Countervailing and Anti-Dumping Duties on Grain

Oriented Flat-rolled Electrical Steel from the United States

Viet Nam, WT/DS404 - United States - Anti-Dumping Measures on Certain Shrimp from Viet

Nam

Ordered by defendants:

Argentina, WT/DS238 - Definitive safeguard measures on imports of preserved peaches

Argentina, WT/DS241 - Anti-dumping duties on poultry from Brazil -

Australia, WT/DS271 - Certain measures affecting the importation of fresh pineapple

Australia, WT/DS270 - Certain measures affecting the importation of fresh fruit and

vegetables

Australia, WT/DS367 - Australia — Measures Affecting the Importation of Apples from New

Zealand

Australia, WT/DS434 - Australia - Certain Measures Concerning Trademarks and Other Plain

Packaging Requirements Applicable to tobacco Products and Packaging

Canada, WT/DS412 - Canada - Certain Measures Affecting the Renewable Energy

Generation Sector

Canada, WT/DS276 - Measures relating to exports of wheat and treatment of imported

grain

Chile, WT/DS207 - Price band system and safeguard measures relating to certain

agricultural products

China, WT/DS309 - Value-added tax on integrated circuits

China, WT/DS427 - China — Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duty Measures on Broiler

Products from the United States

China, WT/DS440 - China — Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duties on Certain

Automobiles from the United States

China, WT/DS398 - China — Measures Related to the Exportation of Various Raw Materials

China, WT/DS413 - China — Certain Measures Affecting Electronic Payment Services

China, WT/DS414 - China — Countervailing and Anti-Dumping Duties on Grain Oriented

Flat-rolled Electrical Steel from the United States

China, WT/DS433 - China - Measures Related to the Exportation of rare Earths, Tungsten

and Molybdenum

China, WT/DS431 - China - Measures Related to the Exportation of rare Earths, Tungsten

and Molybdenum

China, WT/DS363 - Measures affecting trading rights and distribution services for certain

publications and audiovisual entertainment products

China, WT/DS362 - Measures affecting the protection and enforcement of intellectual

property rights

Colombia, WT/DS366 - Colombia - Indicative prices and restrictions on ports of entry

Dominican Republic, WT/DS416 - Dominican Republic — Safeguard Measures on Imports of

Polypropylene Bags and Tubular Fabric

Dominican Republic, WT/DS415 - Dominican Republic — Safeguard Measures on Imports of

Polypropylene Bags and Tubular Fabric

Dominican Republic, WT/DS418 - Dominican Republic — Safeguard Measures on Imports of

Polypropylene Bags and Tubular Fabric

25

______________________________________________________________

Policy Department C: Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs

Dominican Republic, WT/DS417 - Dominican Republic — Safeguard Measures on Imports of

Polypropylene Bags and Tubular Fabric

Dominican Republic, WT/DS302 - Measures affecting the importation and internal sale of

cigarettes

Egypt, WT/DS211 - Definitive anti-dumping measures on steel rebar from Turkey

Egypt, WT/DS305 - Measures affecting imports of textile and apparel products

India, WT/DS430 - India — Measures Concerning the Importation of Certain Agricultural

Products from the United States

India, WT/DS360 - India - Additional and Extra-Additional duties India - Additional and

Extra-Additional duties on imports from the United States

India, WT/DS175 - Measures affecting trade and investment in the motor vehicle sector

India, WT/DS306 - Anti-dumping measure on batteries from Bangladesh

Japan, WT/DS336 - CV duty on DRAMS from Korea

Japan, WT/DS323 - JAPAN – IMPORT QUOTAS ON DRIED LAVER AND SEASONED LAVER

Japan, WT/DS245 - Measures affecting the importation of apples

Korea, Republic of, WT/DS391 - Korea — Measures Affecting the Importation of Bovine

Meat and Meat Products from Canada

Korea, Republic WT/DS312 - Korea — Anti-Dumping Duties on Imports of Certain Paper

from Indonesia

Mexico, WT/DS331 - Mexico ¿ Anti-Dumping Duties on Steel Pipes and Tubes from

Guatemala

Mexico, WT/DS295 - Definitive AD measures on beef and rice.

Mexico, WT/DS308 - Tax measures on soft drinks and other beverages

Mexico, WT/DS204 - Measures affecting telecommunication services - Mexico

WT/DS232 - Measures affecting the import of matches

Moldova, Republic Of, WT/DS421 - Moldova — Measures Affecting the Importation and

Internal Sale of Goods (Environmental Charge)

Nicaragua, WT/DS188 - Measures affecting imports from Honduras and Colombia

Nicaragua, WT/DS201 - Measures affecting imports from Honduras and Colombia (II)

Philippines, WT/DS403 - Philippines — Taxes on Distilled Spirits

Ukraine, WT/DS423 - Ukraine — Taxes on Distilled spirits

United States, WT/DS399 - United States — Measures Affecting Imports of Certain

Passenger Vehicle and Light Truck Tyres from China

United States, WT/DS449 - United States — Countervailing and Anti-dumping Measures on

Certain Products from China

United States, WT/DS404 - United States - Anti-Dumping Measures on Certain Shrimp from

Viet Nam

United States, WT/DS345 - United States — Customs Bond Directive for Merchandise

Subject to Anti-Dumping/Countervailing Duties

United States, WT/DS343 - United States - Measures Relating to Shrimp from Thailand

United States, WT/DS322 - Measures Relating to Zeroing and Sunset Reviews

United States, WT/DS277 - Investigation of the international trade commission in softwood

lumber

United States, WT/DS296 - CV duty investigation on DRAMS

United States, WT/DS282 - Anti-dumping measures on oil country tubular goods

United States, WT/DS420 - United States — Anti-dumping measures on corrosion-resistant

carbon steel flat products from Korea

United States, WT/DS422 - United States — Anti-Dumping Measures on Shrimp and

Diamond Sawblades from China

United States, WT/DS436 - United States — Countervailing Measures on Certain Hot-Rolled

Carbon Steel Flat Products from India

26

______________________________________________________________

Annex A – Arbitrations involving Member States/Switzerland, State Entities and the EU since 1999

United States, WT/DS437 - United States — Countervailing Duty Measures on Certain

Products from China

United States, WT/DS406 - United States — Measures Affecting the Production and Sale of

Clove Cigarettes

United States, WT/DS281 - Anti-dumping measures on cement

United States, WT/DS379 - United States - Definitive Anti - Dumping and Countervailing

duties on certain products from China

United States, WT/DS244 - Sunset review of AD duties on corrosion-resistant carbon steel

flat products

United States, WT/DS184 - Anti-dumping measures on certain hot-rolled steel products

from Japan